1. Introduction

Behavioral impulsiveness can be defined as the preference for smaller and more immediately available rewards over larger, but delayed, rewards, while behavioral self-control is the preference for the latter over the former (Ainslie, 1974; Rachlin & Green, 1972; Logue, 1988; van Baal, Walasek, Verdejo-Garcia, & Hohwy, 2025). The ability to delay the gratification of obtaining a smaller reward and waiting to acquire a larger, but delayed reward, i.e., behavioral self-control, has been displayed to varying degrees across a remarkable number of both mammalian and non-mammalian species (Abeysinghe, Nicol, Hartnell, & Watheet, 2005; Ainslie, 1974; Rachlin & Green, 1972; Tobin & Logue, 1994; Van Haaren, Van Hest, & Van De Poll, 1998; MacLean, Hare, Nunn, & Zhao, 2014; Miller, Boeckle, & Jelbert, 2019; Gobbo & Semrov, 2022). This behavioral capacity even extends to invertebrates, such as honeybees (Apis mellifera; Cheng, Pena, Porter, & Irwin, 2002; Mayack & Naug, 2015) and cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis; Schnell, Boeckle, Rivera, Clayton, & Hanlon, 2021). Traditionally, behavioral impulsiveness and self-control have been experimentally investigated using primary food rewards obtained via either two-key operant choice tasks or instrumental discrete-trial choice tasks (Abeysinghe et al., 2005; Gomes-Ng, Gray, Cowie, 2024; Tobin, Chelonis, & Logue, 1993; Van Haaren et al., 1988; Cheng et al., 2002; Schnell et al., 2021). More recently, a preference for larger yet delayed rewards was demonstrated in African gray parrots (Psittacus erithacus) that received tokens as a secondary reward, as opposed to a primary food reward (Pepperberg & Rosenberger, 2022; for an earlier review of token economies, see Hackenburg, 2009). Taken together, these results indicate that the capacity for behavioral self-control extends beyond mammalian species and is likely the result of behavioral adaptations under various selection pressures.

A species’ capacity for behavioral self-control may be determined by natural history and evolved behavioral capacities (Aellen, Dufour, & Bshary, 2021; Schnell et al., 2021). Animals that rely on transient prey, such as the common cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis), display behavioral self-control in a delay maintenance task (Schnell et al., 2021). Similarly, cleanerfish (Labridae dimidiatus) will routinely ignore smaller fish that present less mucus and wait for larger fish that present a larger amount of mucus for the cleaner fish to feed upon; cleaner fish thus rival primates on quantitative delayed gratification tasks (Aellen et al., 2021). The preceding examples fit within a larger framework under the Life History Hypothesis (Stearns, 1998; for a recent review, see Veit et al., 2025), which posits that organisms must balance tradeoffs among growth, maintenance, and reproduction. For a territorial male Betta splendens, one manner in which these tradeoffs are manifested is found in a male’s choices between defending territory from potential rivals versus courting potentially receptive females who enter their territory (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Forsatkar, Nematollahi, & Brown, 2016; Simpson, 1968). To navigate these tradeoffs successfully, some response patterns (e.g., aggression and territorial defense) must be inhibited. In contrast, other response patterns (e.g., courtship and mating) are activated when a female approaches, while an opposite pattern emerges when a rival male approaches (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Licheck et al., 2022). Thus, the life history hypothesis predicts that territorial males’ reproductive success depends upon how effectively they balance competing demands to enhance fitness by choosing when to activate specific response topographies in one particular context and inhibit these same responses under different contexts. As such, inhibitory control over responding is a necessary feature of survival and fitness in Betta splendens.

More recently, Wooster, Whiting, Nimmo, Sayol, Carthey, Stanton, and Ashton, (2025) proposed the Predatory Intelligence Hypothesis, which postulates that predator-prey interactions produce a co-evolutionary “arms race” that selects for enhanced cognitive traits such as behavioral flexibility, larger spatial/temporal memory capacity, and inhibitory control. It is this final prediction that is of primary interest for the present study. Enhanced inhibitory control offers potential survival advantages, enabling animals to assess risk more effectively, regulate territorial aggression, and optimize energy expenditure/caloric intake during foraging. During active foraging bouts, male Betta splendens demonstrate a well-defined predation sequence (Bateman, Vos, & Anholt, 2014, Endler, 1991) once potential prey are detected (Baenninger & Kraus, 1981). Initial responses typically include slow movements and coasting toward the potential prey while the predator fish remains undetected (Bateman et al., 2014). Once potential prey are identified and localized, the predator fish waits until the closing distance to the prey is small enough that predatory attack in the form of a suction movement results in prey capture (Day, Higham, Holzman, & Van Wassenbergh, 2015; Ferry-Graham, & Lauder, 2001; Wainwright, Carroll, Collar, Day, Higham, et al., 2007; Gromova & Makhotin, 2023). To successfully execute this series of responses, the fish must inhibit its suction feeding response until the moment to perform the predatory attack is optimal. There is a notable sex difference in this response; in male Betta splendens, the gap is 1 gape-length, whereas the gap for female Betta splendens is 1.5 gape-lengths (Cagle, 2014). Therefore, foraging Betta splendens are capable of delaying action before acquiring prey, and the capacity for sustaining the duration of this delayed action may be stronger in males than females. While wild Betta splendens function as predators on a variety of small aquatic prey (Goldstein, 2015; Monvises et al., 2009), they are also subject to predation pressures as prey for avian predators, such as egrets and kingfishers (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001b). As a result, Betta splendens are subjected to bi-directional selection pressures via predator-prey interactions, which could further drive selection for enhanced cognitive capabilities, perhaps including the capacity for behavioral self-control.

Given the existing evidence across diverse taxa as well as several interrelated theoretical and empirical foundations, even domesticated Betta splendens may have the capacity for behavioral self-control. First, research has shown that the ability to delay gratification is not limited to mammals but extends to ecologically diverse non-mammalian species, including birds, cephalopods, and teleost fish (Abeysinghe et al., 2005; Pepperberg & Rosenberger, 2022; Schnell et al., 2021; Aellen et al., 2021) and even other invertebrates (Cheng et al., 2002; Mayack & Naug, 2015; Schnell et al., 2021). Second, both the Life History Hypothesis and the Predatory Intelligence Hypothesis suggest that species under complex ecological and social selection pressures, such as territorial defense, courtship, foraging, and predator avoidance, are more likely to evolve cognitive traits that could include inhibitory and behavioral self-control (Wooster et al., 2025; Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Licheck et al., 2022). In the wild, Betta splendens males are frequently required to suppress one behavior (e.g., aggression) in favor of another (e.g., courtship) depending on the social context, indicating a capacity for context-dependent behavioral regulation (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Licheck et al., 2022). Additionally, their foraging strategies involve precise motor inhibition during predatory strikes, further supporting the presence of temporally extended self-control processes (Day et al., 2015; Ferry-Graham & Lauder, 2001; Wainwright et al., 2007; Cagle, 2014). Taken together, these patterns support the conjecture that male Betta splendens possess the neurobehavioral substrates necessary for behavioral self-control. Therefore, if such cognitive regulation is evident during ecologically relevant tasks, it follows that domesticated Betta splendens may also display this ability in a controlled experimental context involving delayed gratification.

Experiment I for the present study tests the hypothesis that domesticated male Betta splendens are capable of self-control by assessing whether they will opt for a larger, delayed food reward over a smaller, immediate one in a binary choice task, thereby providing critical insight into the evolutionary underpinnings of inhibitory control in a solitary teleost fish species. Subjects in Experiment I were tested in a discrete-choice instrumental response task similar to Craft, Velkey, & Szalda-Petree (2003) to determine if domesticated male Betta splendens will demonstrate a stable preference for a larger-later food reward option over a smaller-sooner option; furthermore, domesticated female Betta splendens were also tested to determine if any sex differences exist in such preferences.

2. Experiment I: Materials and Method

2.1. Animals and Housing

The experimental subjects (N = 95, 52 males and 43 females) were adult, domesticated Betta splendens (> 6 months of age, approximately 6 cm long) obtained from a local retail supplier. Upon arrival at the facility, animals were dip-transferred from their transport cups into the experimental apparatus tank (see following section). Each tank was filled with dechlorinated tap water with water temperatures maintained at 25°C (75.2 °F) ± 1°C. All fish were kept under a 12L:12D photoperiod and fed daily with nine food pellets (“Betta Bio-Gold Baby Pellets”, Hikari, Himeju, Japan). All housing, caretaking, and other procedures involving the animals were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council’s (2011) guidelines for the care and use of animals.

2.2. Materials and Apparatus

Each fish was housed individually in a custom-built acrylic T-maze based upon modifications to the designs used by Craft et al. (2003) and Bols and Hogan (1979). Unlike the double-ended T-mazes used by these previous researchers with a separate start box, runway, and goal box, the individual T-mazes for Experiment I consisted of a single goal box (20.3 x 7.6 x 10.8 cm) and a combined start box/runway (20.3 x 10.2 x 10.8 cm). T-mazes were partially submerged to a depth of 10 cm (approximately 29 liters) within a larger polycarbonate tank (65 x 45 x 15 cm) in pairs separated by fixed, opaque barriers such that the subject in one maze could not see the subject in the other maze. In addition to the two T-mazes, each tank was equipped with a gravel floor, a temperature gauge, a submersible heater, and a small air stone connected to a compressed filtered air supply. During trials, a removable black T-maze divider and a choice door featuring a circular opening for each side of the divider (diameter = 2.54 cm) were used. One half of both the choice door and the T-maze divider was covered with white and blue checkered-pattern contact paper, while the other side of the choice door and the T-maze divider was solid black. The checkered pattern choice door was associated with the delivery of larger-later food reinforcement, while the solid black choice door was associated with the smaller-sooner delivery of food reinforcement.

2.3. Procedure

Prior to the start of experimental trials, fish were acclimated within the T-maze apparatus for 2 days. Trials were performed daily at 9 am, 12 pm, and 3 pm, including weekends. During each trial, subjects swam into the start box/runway and were separated from the goal box by lowering a guillotine door. During this time, the choice door and T-maze divider were inserted into the goal box behind the guillotine door. The left-right orientation of the T-maze divider was randomly alternated across trials, ensuring that the checkered pattern appeared on various sides to control for side bias. Once the T-maze divider and choice door were placed in the tank, the guillotine door was raised, and the subject was allowed to choose between the solid black or blue checkered side by swimming through the corresponding choice door opening. The amount of time the subject spent in the runway after the guillotine door was lifted was measured. Once the subject swam through a choice door, the guillotine door was closed against the choice door so that the subject could not reenter the runway during the trial or enter the other side of the T-maze divider. Once in the goal box, the subject received a manually delivered reward based on the side selected, either one pellet immediately (solid black) or three pellets after a 15-second delay (blue checkered). Subjects remained in the choice box until all pellets of food were consumed. Subjects continued to complete trials every day until stability was reached (8 out of the last 10 trials resulted in the same selection of a particular reward condition). The 5-minute mark indicated that a subject made no choice, at which time the trial was ended and the T-maze divider and choice door were removed. During the first 15 trials of acquisition, forced-choice trials were implemented when necessary to ensure subjects experienced both reward conditions of the experiment. If the subject selected the same reward option throughout five consecutive trials, the opening of the choice door for that option was blocked, forcing the subject to choose the alternative reward condition during the forced-choice trial. After the first 15 trials, no further forced-choice trials were conducted to allow subjects to demonstrate stable preferences. Based upon the daily choice selections of each subject (1 or 3 pellets per trial, maximum of 9 pellets per day), subjects were provided 0 to 6 supplemental pellets in the afternoon to bring their total intake to 9 pellets each day.

A total of 24 subjects (12 males & 12 females) either failed to reach stability or experienced health issues, and subsequently were removed from Exp. I. Data from the remaining 71 subjects were analyzed using SPSS 28.0 for Windows.

The protocols for this research were approved by the Christopher Newport University Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (#2017-6, #2020-6, #2023-8).

3. Experiment I: Results

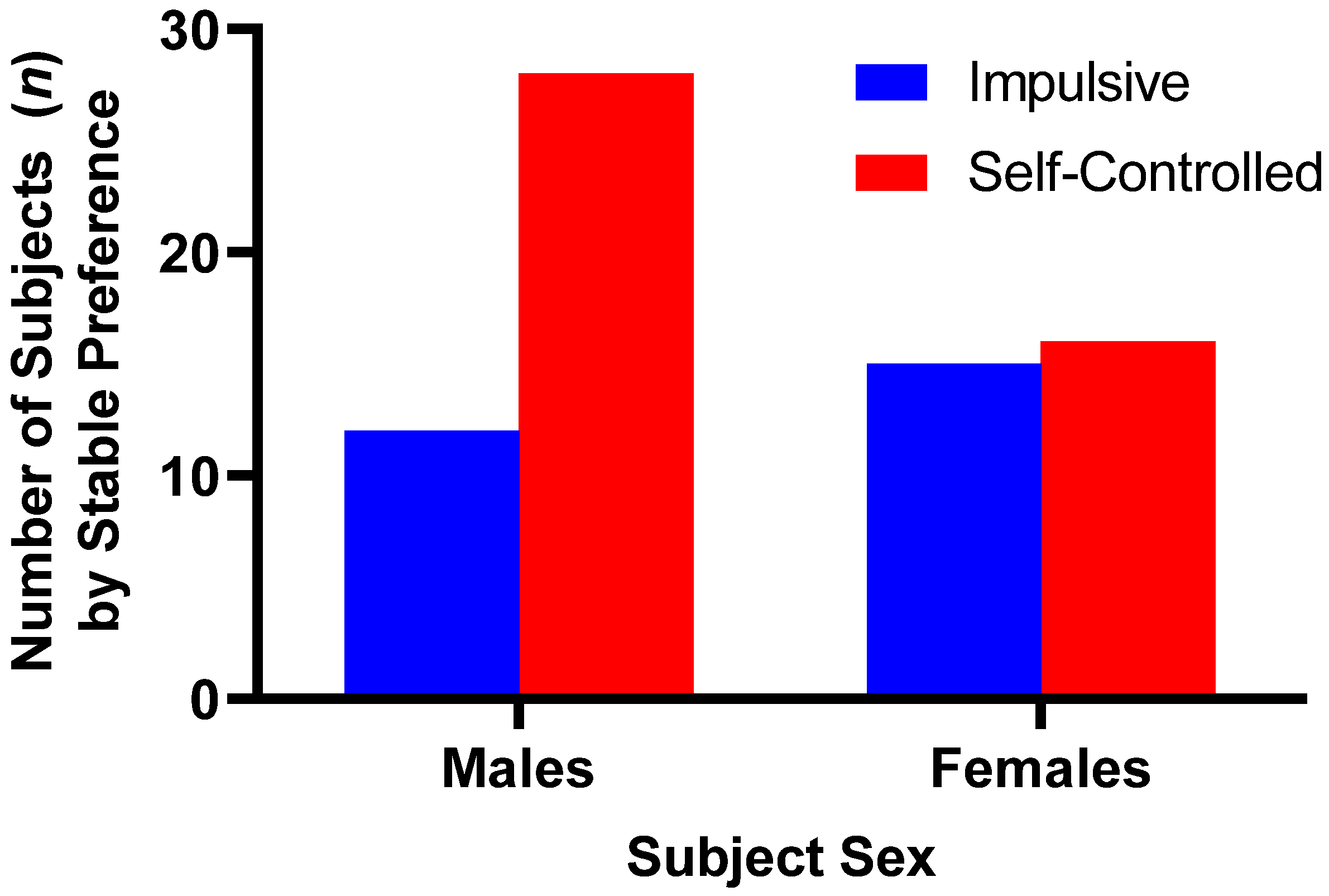

A total of 40 male subjects reached stabilization criteria, with 28 demonstrating a preference for the larger-later reward and 12 demonstrating a preference for the smaller-sooner reward option. Male subjects made significantly more larger-later choices than smaller-sooner choices, χ

2 (1,

n = 40) = 6.4,

p = 0.011. A total of 31 female subjects reached stabilization criteria, with 16 female subjects stabilized on the larger-later reward option while 15 female subjects stabilized on the smaller-sooner reward option; females had no significant preference of larger-later choices over smaller-sooner choices, χ

2 (1,

n = 31) = 0.032,

p = 0.858 (see

Figure 1).

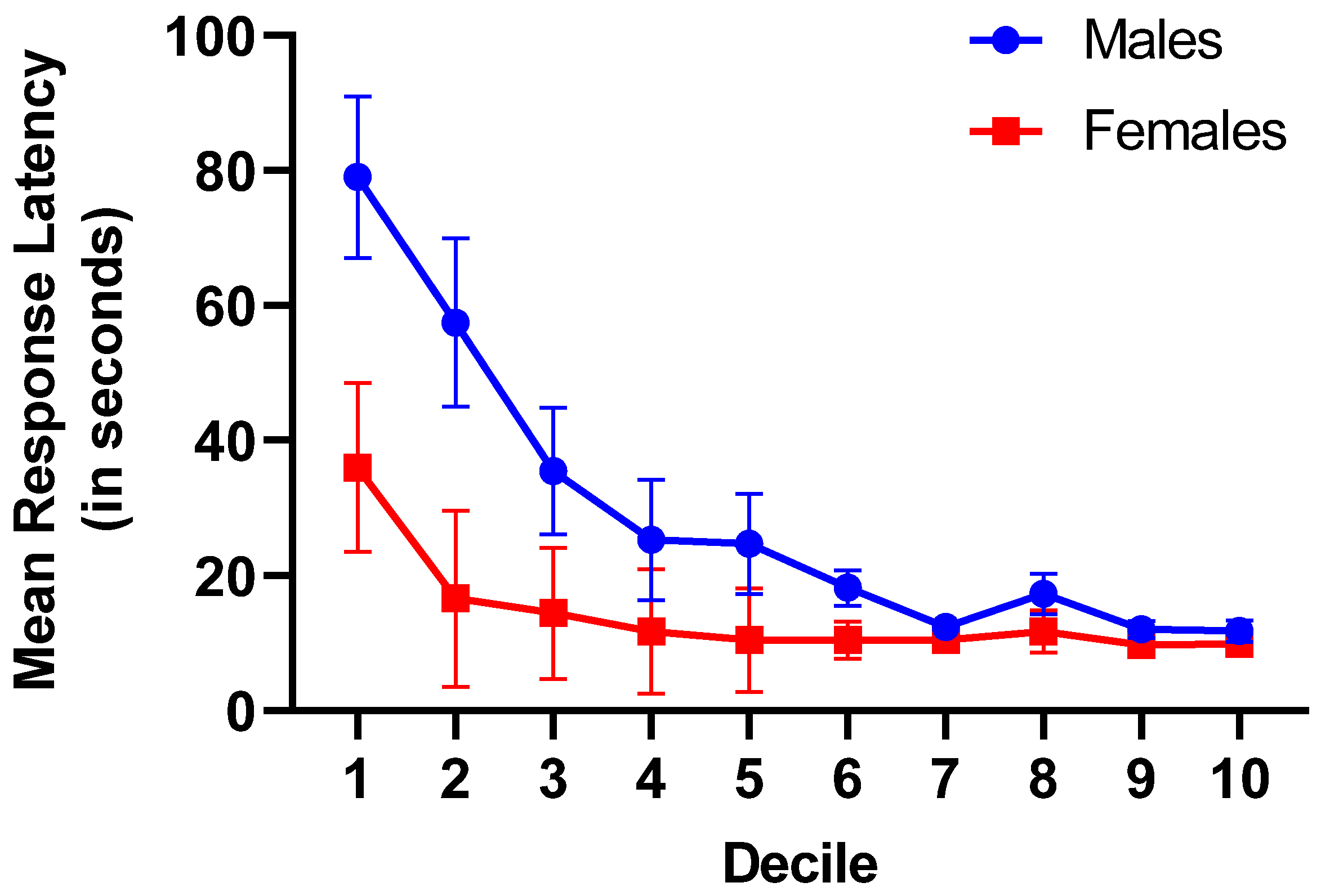

Response latencies across Trials were blocked and averaged to form ten equal deciles. Response latencies were analyzed in a 2 (Sex) x 10 (Decile) mixed-factorial ANOVA. Analysis of choice response times revealed a significant mixed-factor interaction of Decile x Sex on response latencies,

F(9, 621) = 3.73,

p = 0.015, η

p2 = 0.051. Furthermore, main effects were found for both Sex,

F(1, 69) = 7.78, p < 0.007, η

p2 = 0.10, and Decile,

F(9, 621) = 13.11,

p ≤ 0.001, η

p2 = 0.16 (see

Figure 2). Across deciles, male subjects had a longer mean response latency (

M = 31.4 s,

SEM = 4.08 s) than female subjects (

M = 14.2 s,

SEM = 4.6 s). Furthermore, subjects had significantly slower mean response latencies during the first three deciles of acquisition (

M = 41.3 s,

SEM = 7.7 s) than during the last three deciles of preference stability (

M = 12.1 s,

SEM = 1.3 s). The Decile x Sex interaction revealed significantly larger response latencies for male subjects compared to female subjects during acquisition deciles 1-3, while there was no significant difference between the response latencies of male and female subjects during the final deciles 8-10.

4. Experiment I: Discussion

The findings of Experiment I indicate that domesticated male Betta splendens possess the capacity for behavioral self-control. A substantial majority of males (~70%) demonstrated a stable preference for the larger, delayed food reward over the smaller, immediate one, indicating a group-level bias toward delayed gratification. While a subset of male subjects (~30%) displayed impulsive preference for the smaller, immediate food reward over the larger, delayed one, the dominant pattern of behavior reflected the males’ ability to suppress short-term impulses for long-term benefits. These findings support theoretical predictions from the Life History Hypothesis, which posits that ecologically grounded trade-offs (e.g., between aggression and courtship) require context-dependent behavioral regulation (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Licheck et al., 2022). This is further supported by the Predatory Intelligence Hypothesis (Wooster et al., 2025), which suggests that precise predatory strike timing requires motor inhibition and decision latency, both of which are core components of behavioral self-control. In contrast, female subjects showed a near-equal split between preferences for delayed versus immediate rewards, with no statistically significant group-level bias towards one option over the other. This indifference at the group level may reflect underlying ecological distinctions between sexes in natural contexts. Unlike males, female Betta splendens are non-territorial and tend to forage opportunistically, moving between male territories rather than defending fixed resources (Simpson, 1968; Forsatkar et al., 2016). Consequently, the selective pressure on inhibitory control may be weaker in females. These sex-specific behavioral tendencies mirror those reported in other taxa, such as cleanerfish and parrots, where ecological roles shape the development of behavioral capacities (Aellen et al., 2021; Pepperberg & Hartsfield, 2024; Pretot, Bshary, & Brosnan, 2016).

Given the observed behavioral self-control in male, but not female, domesticated

Betta splendens, the second experiment was designed to study a likely neurochemical mechanism underlying the proximate basis for self-control as it pertains to reward valuation and motivated responding. In mammals, the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), amygdala, and hippocampus. This pathway plays a central role in reinforcement learning, reward valuation, and inhibitory control (Alacaro, Huber, & Panksepp, 2007). While there are substantial differences between mammals and the teleost fishes regarding brain structure and organization (for a review, see Diotel, Lubke, Strahle, & Rastegar, 2020), comparative investigations have identified putative homologs of mammalian mesolimbic structures, primarily within the teleost telencephalon (see

Table 1). Recently, Dubeyron and Wallace (2023) conducted social exposure experiments with domesticated male

Betta splendens to combine behavioral assessments with neuroanatomical study to identify and confirm various telencephalic regions in the fish brain implicated in opponent recognition. While Dubeyron and Wallace used a social behavioral assay, their findings confirmed several neuroanatomical and functional homologies in the brain of domesticated

Betta splendens. Mammalian components of the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway include the dorsolateral telencephalon (Dl), the dorsomedial telencephalon (Dm), and the ventral portion of the ventral telencephalon (Vv). While several neurotransmitters play a role in the activity of the mesolimbic pathway, dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter and is found to be highly conserved across vertebrate species (Yamamoto & Vernier, 2011; Pérez-Fernández, Barandela, & Jiménez-López, 2021; for a review, see Costa & Schoenbaum, 2022). Furthermore, DOPA decarboxylase, responsible for catalyzing L-Dopa into dopamine, is also highly conserved across vertebrate species (Yamamoto & Vernier, 2011; Yamamoto, Fontaine, Pasqualini, Vernier, 2015). Relevant to the current study, the role of dopamine regarding reward valuation in mammals and birds is well established (Schultz, 2024; Kobayashi & Schultz, 2014; Lak, Stauffer, & Schultz, 2014; Jin, Yang, Yank, Li, Li, & Shang, 2024). Finally, Collins and Frank (2014) suggest that dopaminergic responses to reward can be attenuated by either delay or infrequency, and enhanced dopaminergic activation occurs more strongly with immediate or more frequent rewards. This hypothesized effect can be studied, in part, by administering either a dopamine precursor (e.g., L-Dopa) or a dopamine agonist (e.g., apomorphine).

Rutledge, Skandali, Dayan, & Dolanet (2015) and Pine, Shiner, Seymour, and Dolan (2010) both investigated the effects of L-Dopa on choice responding in humans, finding that increased dopamine influences risk sensitivity and impulsive responding. Rutledge et al. administered L-Dopa or a placebo to healthy young adult humans and found that participants made riskier economic choices and favored short-term rewards after receiving L-Dopa. Similarly, Pine et al. employed a within-subject design, in which healthy adult humans received L-Dopa, haloperidol, or placebo across sessions while completing an adjusting-delay task, in which they chose between smaller-sooner and larger-later rewards. Pine et al. found that L-Dopa led to a greater preference for immediate rewards, indicating increased impulsivity, while haloperidol had no significant effect. Together, these studies suggest that L-Dopa enhances dopaminergic activity and shifts responding toward riskier and more impulsive choices in humans. Interestingly, patients with Parkinson’s disease and other conditions treated with L-Dopa (i.e., generic Levodopa) or dopamine agonists (e.g., generic Apomorphine HCL) often display gambling addiction, impulsiveness, and increased risk seeking (Santangelo, Barone, Trojano, & Vitale, C, 2013). In their review, Santanegelo et al. (2013) suggest that the delivery of dopamine precursors/agonists in humans reduces the output strength of frontostriatal connections (associated with impulse control in the frontal cortex) and increases the output strength of striatal connections (associated with impulsive drive and a preference for immediate rewards). In addition to tremors activated by the nigrostriatal motor pathway due to the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, patients with Parkinson’s disease often present with diminished executive control and reduced capacity for self-monitoring. The prevalence of pathological gambling and other impulse-control disorders is notably higher in patients with Parkinson’s disease than in the general population (Santanegelo et al., 2013). Multiple studies indicate a strong association between dopamine therapies, including pharmacological Levodopa, and pathological gambling (Culicetto, Impellizzeri, Lo Buono, Marafioti, Di Lorenzo, Sorbera, Brigandì, Quartarone & Marino, 2025; Voon, Hassan, Zuowski, Duff-Canning, De Souza, Fox, Lang, & Miyasaki, 2006; Pirritano, Plastino, Bosco, Gallelli, Siniscalchi, & De Sarro, 2014). These findings collectively underscore the central role of endogenous dopamine in modulating impulsive response and highlight the potential for dopamine-enhancing agents, such as exogenous L-Dopa, to disrupt behavioral self-control in humans and possibly in other animals. As such, the development of an animal model of dopamine-induced impulsiveness could be helpful for biobehavioral researchers.

Given the demonstrated capacity for behavioral self-control by the male Betta splendens in Experiment I and Dubeyron and Wallace’s (2023) recent characterization of the relevant regions in Betta splendens, which are likely homologs to the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway in mammals, this dopaminergic signaling likely plays an essential role in reward-based choice behavior in Betta splendens. The behavioral effects of L-Dopa in human participants, especially increased impulsivity, preference for immediate rewards, and diminished self-control, suggest that artificially increased dopamine levels create a bias towards short-term reward preference. If these effects are conserved across vertebrate taxa, then male Betta splendens receiving oral L-Dopa should exhibit a behavioral shift towards preference for smaller, immediate reward in the discrete-choice instrumental choice task. Specifically, L-Dopa administration is expected to reduce choice latency, especially during the acquisition phase, and increase impulsive preference. Experimental confirmation of this hypothesis would provide compelling evidence for the conservation of the dopaminergic mechanisms underlying impulsive choice and establish Betta splendens as a potential model organism for investigating the neural bases of reward valuation, choice, and impulsiveness/self-control.

5. Experiment II: Materials and Method

5.1. Animals and Housing

The subjects (N = 77) were healthy male adult Siamese Fighting Fish (domesticated Betta splendens) obtained from the same local supplier. Housing and husbandry were the same as Experiment 1.

5.2. Procedure

Upon arrival at the facility, each subject was weighed, and subjects were subsequently matched in pairs based upon weight (weights were used for subsequent dosage calculations). Following the matching procedure, one subject was randomly assigned to the L-Dopa treatment condition while the corresponding member of the pair was assigned to the vehicle-only control condition. Thirty minutes prior to the start of each trial, subjects were given either a ~1 mg vehicle pellet or an ~1 mg pellet with 60 mg/kg dose of L-Dopa (CAS# 53587-29-4, Sigma Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), and subjects were given 10 minutes to consume the pellet. If the subject failed to consume the pellet during the acquisition phase of Experiment II, the trial continued regardless. Subjects were required to consume every pre-trial pellet during the performance phase of Experiment II to demonstrate stable choice preferences. Animals that repeatedly rejected pre-trial pellets were further excluded from Experiment II. All remaining procedural aspects of Experiment I were used identically in Experiment II.

A total of 21 subjects either failed to reach stability or experienced health issues that resulted in their removal from the study. Data from the remaining 56 subjects were analyzed using SPSS 28.0 for Windows.

6. Experiment II: Results

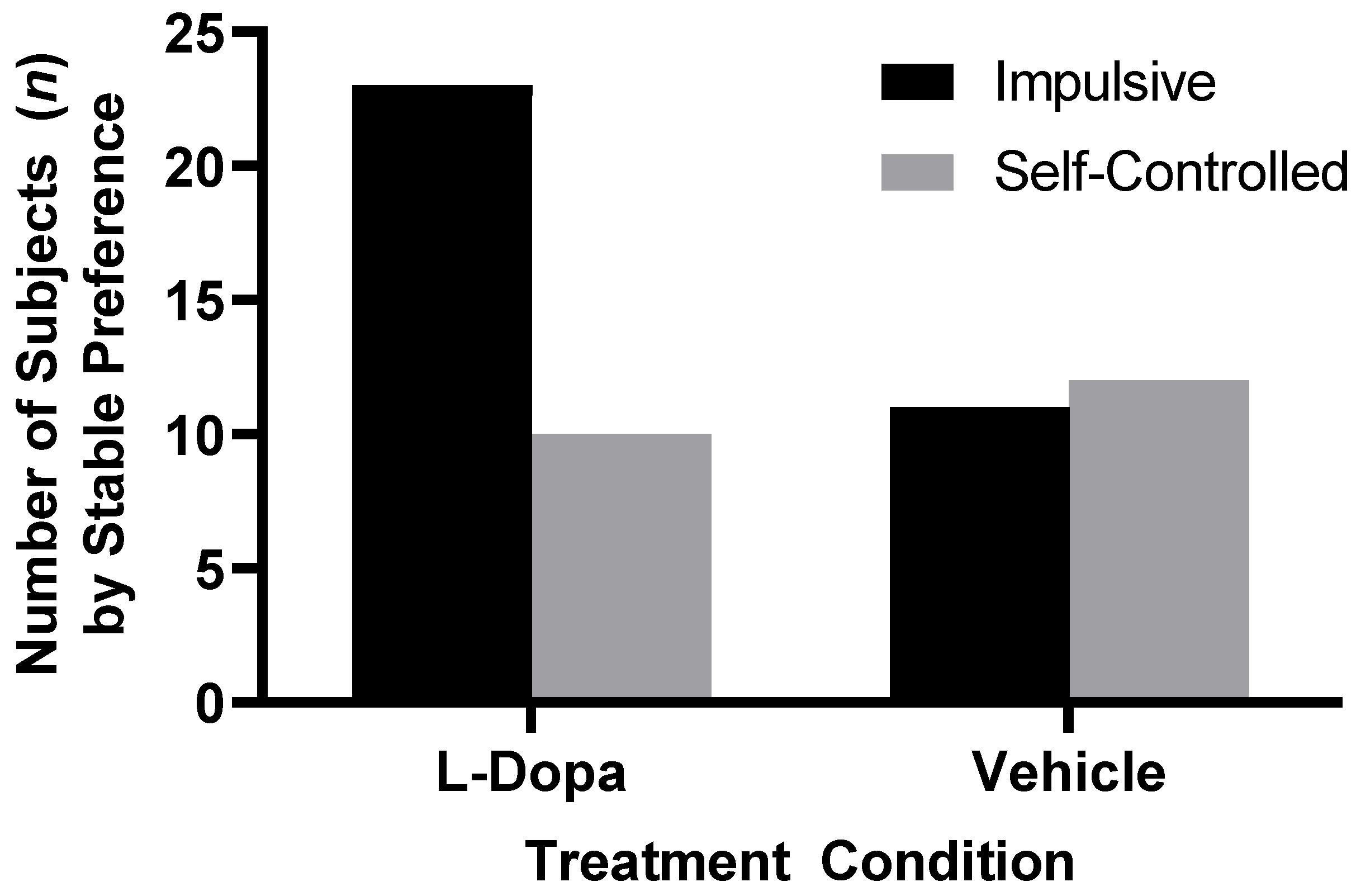

A total of 23 subjects in the vehicle-only control condition reached stabilization criteria, with 12 control subjects stabilized on the larger-later reward option while 11 control subjects stabilized on the smaller-sooner reward option; control subjects had no significant preference between larger-later rewards and smaller-sooner rewards, χ

2 (1,

n = 23) = 0.043,

p = 0.835. A total of 33 subjects in the L-Dopa condition reached stabilization criteria, with only 10 L-Dopa subjects demonstrating a preference for the larger-later reward, while 23 L-Dopa subjects stabilized on the smaller-sooner reward option. Subjects in the L-Dopa condition had significantly fewer larger-later choices than smaller-sooner choices, χ

2 (1,

n = 33) = 5.12,

p = 0.024 (see

Figure 3).

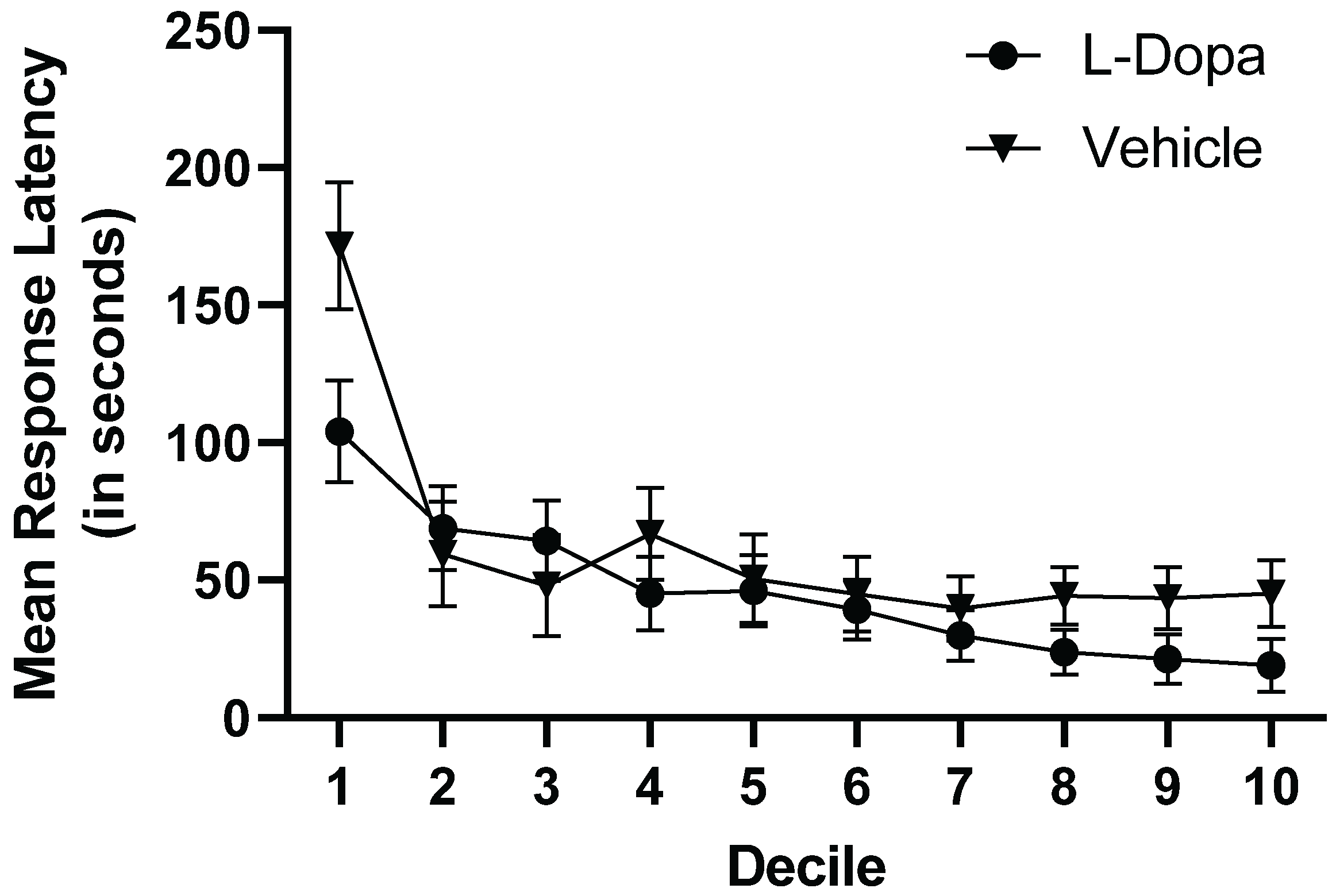

Response latency across Trials were blocked and averaged to form ten equal deciles. Response latencies were analyzed in a 2 (Treatment Condition) x 10 (Decile) mixed-factorial ANOVA. There was a significant mixed-factor interaction of Deciles x Treatment Group,

F(9,468) = 2.441,

p = 0.010, η

p2 = 0.045 (see

Figure 4) as well as there was a main effect of deciles on response latencies with significantly faster response times in later deciles,

F(9, 468) = 18.35,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.261 (see

Figure 4). There was no significant main effect of treatment condition on response latencies,

F(1, 52) = 1.093,

p = 0.301, η

p2 = 0.021

7. Experiment II: Discussion

The results of Experiment II support the hypothesis that increased dopaminergic activity disrupts behavioral self-control in male Betta splendens, as subjects administered oral L-Dopa had a strong preference for the smaller-sooner reward, consistent with impulsive responding (Rutledge et al., 2015; Pine et al., 2010). However, males in the vehicle-only group did not demonstrate a significant preference for the larger-later reward, unlike the substantial majority of male subjects in Experiment I. Rather, the males in the vehicle-only group displayed a preference distribution similar to the female subjects in Experiment I, who demonstrated no group-level preference bias. This particular finding suggests that administering a small, consumable, and unearned reward before each trial may alter baseline reward preference behavior in the discrete-trial instrumental choice task. Furthermore, the similarity between the vehicle-only male subjects in Experiment II and the female subjects in Experiment I may indicate either a contextual shift in motivational state or a reduction in the ecological relevance of the reward contingencies under a slightly modified procedure. Notably, the L-Dopa subjects’ preference for immediate reward was significantly greater than the indifference demonstrated by the vehicle-only group, indicating that the dopaminergic manipulation produced the shift to impulsive preference in the experimental group. These findings are further supported by the Decile by Treatment Group interaction in response latencies, where L-Dopa-treated subjects exhibited faster response latencies at the beginning of the acquisition phase and again during the performance phase, a pattern consistent with reduced response processing and increased impulsive responding (Collins & Frank, 2014; Schultz, 2024). Taken together, these findings indicate that dopamine plays a central and evolutionarily conserved role in modulating behavioral self-control in Betta splendens.

8. General Discussion

Across Experiments I and II, the current study demonstrates that domesticated male Betta splendens exhibit a stable and observable capacity for behavioral self-control in the discrete-choice instrumental response task. This capacity is disrupted by the administration of oral L-Dopa. In Experiment I, males demonstrated a substantial preference for the larger-later reward option over the smaller-soon alternative; 70% of males stabilized on the delayed-reward option. This behavioral capacity is further demonstrated by the significantly longer response latencies among male subjects during the early acquisition phase of the experiment, which provides a pattern of responding consistent with behavioral self-control (Logue, 1988; Rachlin & Green, 1972; Tobin & Logue, 1994). In contrast, female subjects in Experiment I did not demonstrate any group-level preference for either reward option, and their response latencies were shorter and more stable across deciles, suggesting less engagement of response inhibition during experimental trials. These sex differences are consistent with the Life History Hypothesis (Stearns, 1998) and ecological observations that male Betta splendens, as territorial and selective foragers, are under stronger selection pressures that favor behavioral inhibition (Jaroensutasinee & Jaroensutasinee, 2001a; Forsatkar et al., 2016). In the wild, male Betta splendens must frequently suppress aggression to engage in courtship with receptive females or to surface-feed and tend fertilized eggs in their bubble nest. Additionally, males must delay predatory strikes for optimal timing during prey acquisition and regulate energy expenditure during courtship, foraging, and defense; collectively, these response patterns involve behavioral self-control (Cagle, 2014; Day et al., 2015; Wooster et al., 2024).

In Experiment II, administration of oral L-Dopa to the experimental group produced a marked shift towards impulsive preference. While the vehicle-only group demonstrated group-level indifference in preference with a nearly equal distribution between smaller-sooner and larger-later options, similar to the female subjects in Experiment I, the L-Dopa group showed a significant preference for the smaller-sooner reward, consistent with increased impulsivity. Notably, this shift in preference was accompanied by a significant interaction between decile and treatment, where subjects in the L-Dopa condition exhibited shorter response latencies during both the early acquisition and later performance phases of the experiment, consistent with increased impulsive action (Collins & Frank, 2014; Schultz, 2024). These findings are consistent with the results of human studies demonstrating that exogenous L-Dopa increases risk preference and diminishes tolerance in reward delays (Rutledge et al., 2015; Pine et al., 2010) as well as with clinical research indicating that dopamine-enhancing treatments such as Levodopa and dopamine agonists are associated with increased risks for impulse-control disorders and gambling addiction in patients with Parkinson’s disease (Santangelo et al., 2013; Voon et al., 2006; Culicetto et al., 2025 Pirritano et al., 2014). The results from Experiment II extend these findings to a non-mammalian vertebrate, suggesting that dopaminergic signaling modulates behavioral self-control in an evolutionarily conserved manner.

The results of the present study provide empirical support for the theoretical and ecological frameworks reviewed in the Introduction. Specifically, the Predatory Intelligence Hypothesis (Wooster et al., 2025) posits that predator-prey interactions select for enhanced cognitive capacities, and our findings align with this framework. Male Betta splendens not only demonstrated behavioral self-control in the foraging context of the discrete-trial instrumental choice task, but their performance was modulated by manipulation of the dopaminergic system. These results add to the growing body of literature suggesting that self-control and delay of gratification are not uniquely human or even mammalian traits, but are distributed across several taxa as driven by ecological demands (MacLean et al., 2014; Schnell et al., 2021; Aellen et al., 2021; Pepperberg & Rosenberger, 2022). Furthermore, the functional dopaminergic homologies between fish telencephalic regions and mammalian mesolimbic structures provide a neurofunctional basis for the observed parallels in these behaviors across taxa (O’Connell & Hofmann, 2011; Yamamoto & Vernier, 2011; Salas et al., 2003). Within this framework, Betta splendens can serve as a viable comparative model for further study on the neural substrates of reward valuation and behavioral regulation.

Nonetheless, the current study has several limitations that should be noted here. While the results support the conclusion that endogenous L-Dopa increases impulsivity by increasing dopamine levels in the aforementioned pathway, the present study does not include a dose-response curve or multiple pharmacological manipulations (e.g., direct dopamine agonism or antagonism) to more fully characterize the extent to which dopamine plays a role in reward valuation and behavioral self-control in Betta splendens. Additionally, the procedural differences between the two experiments, particularly the administration of a small, unearned food pellet before each trial in Experiment II, may have altered motivational drive or reward salience in the vehicle-only group, thereby reducing comparability across the two experiments. Finally, only male subjects were used in Experiment II, as they demonstrated behavioral self-control in Experiment I. Future work should explore the extent to which female Betta splendens exhibit similar dopaminergic modulation when tested under similar pharmacological conditions.

In addition to addressing the previously-mentioned limitations, future research can expand upon the current findings. For example, follow-up studies could explore a fuller range of pharmacological manipulations across dose ranges, dopamine antagonists, or selective D1v/D2v receptor agents to better characterize the receptor-specific aspects of dopaminergic regulation of behavioral self-control. In addition, activity in telencephalic regions homologous to the mammalian mesolimbic pathway could be assessed with molecular techniques, e.g., immediate early gene expression, following demonstrated preference in order to provide more direct evidence of neural pathway involvement. Future researchers could also study wild-type Betta splendens or other teleost species from various ecological niches to determine how environmental and selection pressures shape response traits such as behavioral self-control. Finally, other behavioral approaches such as effort-based choice responding, probabilistic reward tasks, or response inhibition, (e.g., the five-choice serial reaction time task; Fizet, Cassel, Kelche, & Meunier, 2016) combined with various bioassays would provide broader understanding of how dopamine and other catecholamine systems influence aspects of reward-mediated responding in teleost species (Rink & Wullimann, 2002). Collectively, these future directions could establish domesticated Betta splendens as a useful model for studying the evolution and neurobiology of behavioral self-control across vertebrates.

9. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that domesticated male Betta splendens exhibit a clear capacity for behavioral self-control, as evidenced by their preference for larger, delayed rewards in a discrete-choice instrumental task, and that this capacity can be disrupted by oral administration of L-Dopa. The findings provide support for the Life History Hypothesis and the Predatory Intelligence Hypothesis by showing that males, but not females, display a stable preference for delayed rewards, consistent with the ecological pressures faced by territorial males in the wild. Moreover, Experiment II revealed that enhancing dopaminergic activity via oral L-Dopa shifted male behavior toward impulsive choice, paralleling human and clinical findings linking dopamine increases to impulsivity and risk-taking. These results highlight the evolutionary conservation of dopaminergic mechanisms involved in reward valuation and inhibitory control, reinforcing the functional homologies between fish telencephalic regions and the mammalian mesolimbic pathway. While additional research is necessary to explore dose-response effects, receptor-specific mechanisms, and sex differences under pharmacological manipulation, the current findings establish a foundation for comparative studies on the neural substrates of decision-making. As such, domesticated Betta splendens are a promising animal model for investigating the neurobiological bases of impulsiveness and behavioral self-control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Data File S1: Data1, Data File S2: Data2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and K.W.; methodology, A.V.; software, N/A; validation, A.V.; formal analysis, A.V.; investigation, K.W., N.W., A.A., G.D-A., I.T., and B.W.; resources, A.V. and K.W.; data curation, A.V; writing—original draft preparation, A.V., K.W., N.W., A.A., G.D-A., I.T., and B.W.; writing—review and editing, A.V., K.W., N.W., A.A., G.D-A., I.T., and B.W.; visualization, A.V. and K.W.; supervision, A.V.; project administration, A.V., K.W., N.W., A.A., and G.D-A.; funding acquisition, K.W. and G.D-A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported with funding provided to K.W. and G.D-A. under the undergraduate Summer Scholars Program through the Office for Research and Creative Activity at Christopher Newport University. Additional funding was provided to K.W. under a Nu Rho Psi Undergraduate Research and Travel Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of CHRISTOPHER NEWPORT UNIVERSITY (protocols #2017-6, #2020-6, #2023-8).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank numerous undergraduate research assistants on The FishLab team at Christopher Newport University for their contributions to animal husbandry, data collection, and data entry. Portions of these data were presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in Chicago, IL, USA, in October 2024. During the preparation of this manuscript, the primary author used Scholar GPT 4o for the purposes of generating Table 1 from provided article summaries as well as reviewing clarity and cohesion in the Introduction and Discussion sections. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abeyesinghe, S.M., Nicol, C.J., Hartnell, S.J., & Wathes, C.M. (2005). Can domestic fowl, Gallus gallus domesticus, show self-control? Animal Behaviour, 70, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Aellen, M., Dufour, V., & Bshary, R. (2021). Cleaner fish and other wrasse match primates in their ability to delay gratification. Animal Behaviour, 176, 125-143. [CrossRef]

- Ainslie G.W. (1974). Impulse control in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 21, 485-489. [CrossRef]

- Alcaro, A., Huber, R., & Panksepp, J. (2007). Behavioral functions of the mesolimbic dopaminergic system: an affective neuroethological perspective. Brain Research Reviews, 56, 283-321. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A. W., Vos, M., & Anholt, B. R. (2014). When to defend: Antipredator defenses and the predation sequence. The American Naturalist, 183, 847-855. [CrossRef]

- Baenninger, R., & Kraus, S. (1981). Some determinants of aggressive and predatory responses in Betta splendens. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 95, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Bols, R.J., & Hogan, J.A. (1979). Runway behavior of Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) for aggressive display and food reinforcement. Animal Learning & Behavior, 7, 537–542. [CrossRef]

- Cagle, M. D. (2014). Sexual dimorphism and potential hormonal modulation of feeding mechanics in Siamese fighting fish, Betta splendens (Unpublished Master’s thesis, Northern Arizona University). Retrieved from https://cnu.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/sexual-dimorphism-potential-hormonal-modulation/docview/1611782153/se-2?accountid=10100 on 20 June, 2025.

- Costa, K. M., & Schoenbaum, G. (2022). Dopamine. Current Biology, 32, R817-R824. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K., Peña, J., Porter, M. A., & Irwin, J. D. (2002). Self-control in honeybees. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 259-263. [CrossRef]

- Craft, B.B., Velkey, A.J., & Szalda-Petree, A. (2003). Instrumental conditioning of choice behavior in male Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens). Behavioural Processes, 63, 171-175. [CrossRef]

- Culicetto, L., Impellizzeri, F., Lo Buono, V., Marafioti, G., Di Lorenzo, G., Sorbera, C., Brigandì, A., Quartarone, A., & Marino, S. (2025). Gambling disorder in Parkinson’s disease: A scoping review on the challenge of rehabilitation strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14, 737. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A. G., & Frank, M. J. (2014). Opponent actor learning (OpAL): Modeling interactive effects of striatal dopamine on reinforcement learning and choice incentive. Psychological Review, 121, 337-366. [CrossRef]

- Day, S. W., Higham, T. E., Holzman, R., & Van Wassenbergh, S. (2015). Morphology, kinematics, and dynamics: the mechanics of suction feeding in fishes. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 55, 21-35. [CrossRef]

- Diotel, N., Lübke, L., Strähle, U., & Rastegar, S. (2020). Common and distinct features of adult neurogenesis and regeneration in the telencephalon of zebrafish and mammals. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 568930. [CrossRef]

- Dupeyron, S., & Wallace, K. J. (2023). Quantifying the neural and behavioral correlates of repeated social competition in the fighting fish Betta splendens. Fishes, 8, 384. [CrossRef]

- Endler, J. A. (1991). Variation in the appearance of guppy color patterns to guppies and their predators under different visual conditions. Vision Research, 31, 587–608. [CrossRef]

- Ferry-Graham, L. A., & Lauder, G. V. (2001). Aquatic prey capture in ray-finned fishes: A century of progress and new directions. Journal of Morphology, 248, 99-119. [CrossRef]

- Fizet, J., Cassel, J. C., Kelche, C., & Meunier, H. (2016). A review of the 5-Choice Serial Reaction Time (5-CSRT) task in different vertebrate models. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 135-153. [CrossRef]

- Forsatkar, M. N., Nematollahi, M. A., & Brown, C. (2016). Social context modulates aggression and courtship in male Siamese fighting fish, Betta splendens. Behavioral Processes, 133, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Gobbo, E., & Zupan Šemrov, M. (2022). Dogs exhibiting high levels of aggressive reactivity show impaired self-control abilities. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 869068. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.J. (2015). The Betta Handbook. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series.

- Gomes-Ng, S., Gray, Q., & Cowie, S. (2025). Pigeons’ (Columba livia) intertemporal choice in binary-choice and patch-leaving contexts. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 139, 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Gromova, E. S., & Makhotin, V. V. (2023). Diversity of feeding methods in Teleosts (Teleostei) in the context of the morphology of their jaw apparatus. Inland Water Biology, 16, 700-721. [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, T. D. (2009). Token reinforcement: A review and analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 91, 257-286. [CrossRef]

- Jaroensutasinee, M., & Jaroensutansinee, K. (2001). Bubble nest habitat characteristics of wild Siamese fighting fish. Journal of Fish Biology, 58, 1311-1319. [CrossRef]

- Jaroensutasinee, M., & Jaroensutasinee, K. (2001). Sexual size dimorphism and male contest in wild Siamese fighting fish. Journal of Fish Biology, 59, 1614-1621. [CrossRef]

- Jin, F., Yang, L., Yang, L., Li, J., Li, M., & Shang, Z. (2024). Dynamics learning rate bias in pigeons: insights from reinforcement learning and neural correlates. Animals, 14, 489. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S., & Schultz, W. (2014). Reward contexts extend dopamine signals to unrewarded stimuli. Current Biology, 24, 56-62. [CrossRef]

- Lak, A., Stauffer, W. R., & Schultz, W. (2014). Dopamine prediction error responses integrate subjective value from different reward dimensions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 2343-2348. [CrossRef]

- Lichak, M. R., Barber, J. R., Kwon, Y. M., Francis, K. X., & Bendesky, A. (2022). Care and use of Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) for research. Comparative medicine, 72, 169-180. [CrossRef]

- Logue, A. W. (1988). Research on self-control: An integrating framework. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11, 665-679. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, E. L., Hare, B., Nunn, C. L., Addessi, E., Amici, F., Anderson, R. C., ... & Zhao, Y. (2014). The evolution of self-control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, E2140-E2148. [CrossRef]

- Mayack, C., & Naug, D. (2015). Starving honeybees lose self-control. Biology letters, 11, 20140820. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R., Boeckle, M., Jelbert, S. A., Frohnwieser, A., Wascher, C. A., & Clayton, N. S. (2019). Self-control in crows, parrots and nonhuman primates. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 10, e1504. [CrossRef]

- Monvises, A., Nuangsaeng, B., Sriwattanarothai, N., & Panijpan, B. (2009). The Siamese fighting fish: well-known generally but little-known scientifically. ScienceAsia, 35, 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T. (2012). What is the thalamus in zebrafish? Frontiers in neuroscience, 6, 64. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (2011). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: 8th ed.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, L. A., & Hofmann, H. A. (2011). The vertebrate mesolimbic reward system and social behavior network: a comparative synthesis. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 519, 3599-3639. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, J., Barandela, M., & Jiménez-López, C. (2021). The dopaminergic control of movement-evolutionary considerations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22, 11284. [CrossRef]

- Pepperberg, I. M., & Hartsfield, L. A. (2024). A study of executive function in grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus): Experience can affect delay of gratification. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 138, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Pepperberg, I. M., & Rosenberger, V. A. (2022). Delayed gratification: A grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus) will wait for more tokens. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 136, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Pine, A., Shiner, T., Seymour, B., & Dolan, R. J. (2010). Dopamine, time, and impulsivity in humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 8888-8896. [CrossRef]

- Pirritano, D., Plastino, M., Bosco, D., Gallelli, L., Siniscalchi, A., & De Sarro, G. (2014). Gambling disorder during dopamine replacement treatment in Parkinson’s disease: A comprehensive review. BioMed Research International, 2014, 728038. [CrossRef]

- Prétôt, L., Bshary, R., & Brosnan, S. F. (2016). Factors influencing the different performance of fish and primates on a dichotomous choice task. Animal Behaviour, 119, 189-199. [CrossRef]

- Rachlin, H., & Green, L. (1972). Commitment, choice and self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 17, 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Rink, E., & Wullimann, M. F. (2002). Development of the catecholaminergic system in the early zebrafish brain: An immunohistochemical study. Developmental brain research, 137, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, R. B., Skandali, N., Dayan, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2015). Dopaminergic modulation of decision making and subjective well-being. Journal of Neuroscience, 35, 9811-9822. [CrossRef]

- Salas, C., Broglio, C., & Rodríguez, F. (2003). Evolution of forebrain and spatial cognition in vertebrates: conservation across diversity. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 62, 72-82. [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G., Barone, P., Trojano, L., & Vitale, C. (2013). Pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease. A comprehensive review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 19, 645-653. [CrossRef]

- Schnell, A. K., Boeckle, M., Rivera, M., Clayton, N. S., & Hanlon, R. T. (2021). Cuttlefish exert self-control in a delay of gratification task. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 288, 20203161. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. (2024). A dopamine mechanism for reward maximization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121, e2316658121. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M. J. A. (1968). The display of the Siamese fighting fish, Betta splendens. Animal Behaviour Monographs, 1, 1–73. [CrossRef]

- Stearns, S. C. (1998). The Evolution Of Life Histories. Oxford: Oxford Academic. (Online edn,, 31 Oct. 2023),. [CrossRef]

- Tobin, H., Chelonis, J. J., & Logue, A. W. (1993). Choice in self-control paradigms using rats. The Psychological Record, 43, 441–453.

- Tobin, H., & Logue, A.W. (1994). Self-control across species (Columba livia, Homo sapiens, and Rattus norvegicus). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 108, 126-133. [CrossRef]

- van Baal, S. T., Walasek, L., Verdejo-García, A., & Hohwy, J. (2025). Impulsivity and self-control as timeless concepts: A conceptual analysis of intertemporal choice. Decision, 12, 165–189. [CrossRef]

- Van Haaren, F., Van Hest, A., & Van De Poll, N. E. (1988). Self-control in male and female rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 49, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Veit, W., Gascoigne, S. J., & Salguero-Gómez, R. (2025). Evolution, complexity, and life history theory. Biological Theory, 20, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Voon, V., Hassan, K., Zurowski, M., Duff-Canning, S., De Souza, M., Fox, S., Lang, A., & Miyasaki, J. (2006). Prospective prevalence of pathologic gambling and medication association in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 66, 1750-1752. [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, P., Carroll, A. M., Collar, D. C., Day, S. W., Higham, T. E., & Holzman, R. A. (2007). Suction feeding mechanics, performance, and diversity in fishes. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 47, 96-106. [CrossRef]

- Wooster, E., Whiting, M., Nimmo, D., Sayol, F., Carthey, A., Stanton, L., & Ashton, B. (2025). Predator-prey interactions as drivers of cognitive evolution (preprint). EcoEvoRxiv. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K., & Vernier, P. (2011). The evolution of dopamine systems in chordates. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 5, 21. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K., Fontaine, R., Pasqualini, C., & Vernier, P. (2015). Classification of dopamine receptor genes in vertebrates: Nine subtypes in osteichthyes. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 86, 164-175. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).