Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Viral Isolates and Maintenance

Plant Material and Inoculum

Experimental Design, Data Collection, and Analyses

Results

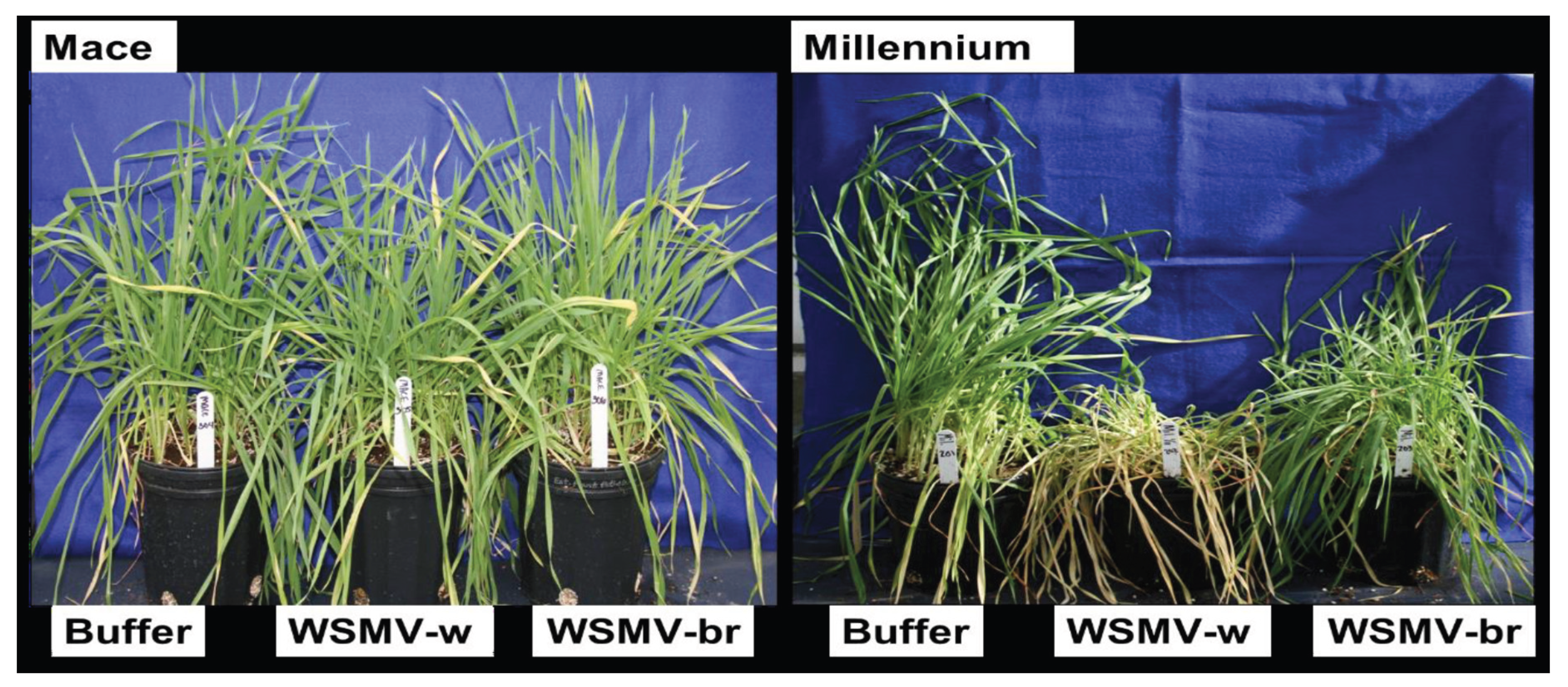

Viral Symptoms: Growth Chamber

Viral Symptoms: Greenhouse

Plant Growth Characteristics: GC and GH

Discussion

Acknowledgements

References

- E. Byamukama et al., “Quantification of yield loss caused by Triticum mosaic virus and Wheat streak mosaic virus in winter wheat under field conditions,” Plant disease, vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 127-133, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Pradhan, Q. Xue, K. E. Jessup, B. Hao, J. A. Price, and C. M. Rush, “Physiological responses of hard red winter wheat to infection by Wheat streak mosaic virus,” Phytopathology, vol. 105, no. 5, pp. 621-627, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Rotenberg et al., “Occurrence of viruses and associated grain yields of paired symptomatic and nonsymptomatic tillers in Kansas winter wheat fields,” Phytopathology, vol. 106, no. 2, pp. 202-210, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Slykhuis, “Aceria tulipae Keifer (Acarina: Eriophyidae) in relation to the spread of wheat streak mosaic,” 1955.

- M. D. Robinson and T. D. Murray, “Genetic variation of Wheat streak mosaic virus in the United States Pacific Northwest,” Phytopathology, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 98-104, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Velandia, R. M. Rejesus, D. C. Jones, J. A. Price, F. Workneh, and C. M. Rush, “Economic impact of Wheat streak mosaic virus in the Texas High Plains,” Crop protection, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 699-703, 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Hunger, J. Sherwood, C. Evans, and J. Montana, “Effects of planting date and inoculation date on severity of wheat streak mosaic in hard red winter wheat cultivars,” 1992.

- J. Price, F. Workneh, S. Evett, D. Jones, J. Arthur, and C. Rush, “Effects of Wheat streak mosaic virus on root development and water-use efficiency of hard red winter wheat,” Plant Disease, vol. 94, no. 6, pp. 766-770, 2010.

- B. Hadi, M. Langham, L. Osborne, and K. Tilmon, “Wheat streak mosaic virus on wheat: biology and management,” Journal of Integrated Pest Management, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. J1-J5, 2011.

- K. Singh, S. N. Wegulo, A. Skoracka, and J. K. Kundu, “Wheat streak mosaic virus: a century old virus with rising importance worldwide,” Molecular Plant Pathology, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 2193-2206, 2018.

- A. R. Stilwell, D. C. Rundquist, D. B. Marx, and G. L. Hein, “Differential spatial gradients of wheat streak mosaic virus into winter wheat from a central mite-virus source,” Plant Disease, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 338-344, 2019.

- G. Orlob, “Feeding and transmission characteristics of Acería tulipae Keifer as vector of Wheat streak mosaic virus,” 1966.

- S. J. Vincent, B. A. Coutts, and R. A. Jones, “Effects of introduced and indigenous viruses on native plants: Exploring their disease causing potential at the agro-ecological interface,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 3, p. e91224, 2014.

- D. Seifers, T. Martin, T. Harvey, S. Haber, and S. Haley, “Temperature sensitivity and efficacy of Wheat streak mosaic virus resistance derived from CO960293 wheat,” Plant Disease, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 623-628, 2006.

- R. A. Graybosch et al., “Registration of ‘Mace’hard red winter wheat,” Journal of Plant Registrations, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 51-56, 2009.

- G. L. Sharp et al., “Field evaluation of transgenic and classical sources of wheat streak mosaic virus resistance,” Crop Science, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 105-110, 2002.

- E. N. Wosula, S. Tatineni, S. N. Wegulo, and G. L. Hein, “Effect of temperature on wheat streak mosaic disease development in winter wheat,” Plant disease, vol. 101, no. 2, pp. 324-330, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Tatineni, R. A. Graybosch, G. L. Hein, S. N. Wegulo, and R. French, “Wheat cultivar-specific disease synergism and alteration of virus accumulation during co-infection with Wheat streak mosaic virus and Triticum mosaic virus,” Phytopathology, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 230-238, 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Lehnhoff, Z. Miller, F. Menalled, D. Ito, and M. Burrows, “Wheat and barley susceptibility and tolerance to multiple isolates of Wheat streak mosaic virus,” Plant Disease, vol. 99, no. 10, pp. 1383-1389, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Hall, R. French, T. J. Morris, and D. C. Stenger, “Structure and temporal dynamics of populations within wheat streak mosaic virus isolates,” Journal of Virology, vol. 75, no. 21, pp. 10231-10243, 2001.

- J. E. McNeil, R. French, G. L. Hein, P. S. Baenziger, and K. M. Eskridge, “Characterization of genetic variability among natural populations of wheat streak mosaic virus,” Phytopathology, vol. 86, no. 11, pp. 1222-1227, 1996.

- Fuentes-Bueno, J. A. Price, C. M. Rush, D. L. Seifers, and J. P. Fellers, “Triticum mosaic virus isolates in the southern Great Plains,” Plant disease, vol. 95, no. 12, pp. 1516-1519, 2011.

- D. Ito, Z. Miller, F. Menalled, M. Moffet, and M. Burrows, “Relative susceptibility among alternative host species prevalent in the Great Plains to Wheat streak mosaic virus,” Plant Disease, vol. 96, no. 8, pp. 1185-1192, 2012.

- E. Wosula, A. J. McMechan, C. Oliveira-Hofman, S. N. Wegulo, and G. Hein, “Differential transmission of two isolates of Wheat streak mosaic virus by five wheat curl mite populations,” Plant disease, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 154-158, 2016.

- B. Siriwetwiwat, Interactions between the wheat curl mite, Aceria tosichella Keifer (Eriophyidae), and wheat streak mosaic virus and distribution of wheat curl mite biotypes in the field. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2006.

- R. A. Jones, “Plant virus emergence and evolution: origins, new encounter scenarios, factors driving emergence, effects of changing world conditions, and prospects for control,” Virus research, vol. 141, no. 2, pp. 113-130, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Fahim, A. Mechanicos, L. Ayala-Navarrete, S. Haber, and P. Larkin, “Resistance to wheat streak mosaic virus–a survey of resources and development of molecular markers,” Plant Pathology, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 425-440, 2012. [CrossRef]

| Rate (score) | Score description |

|---|---|

| 1 | No disease symptoms |

| 2 | Light mottling [1-10%] |

| 3 | Advanced mottling [11-25%] |

| 4 | Severe mottling [26-40%] and stunting |

| 5 | Severe mottling [>40%], stunting and chlorosis |

| Viral severity score | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mace | Millennium | ||||

| Isolate | Isolate | ||||

| WSMV-br | WSMV-w | WSMV-br | WSMV-w | ||

| No symptoms (score 1) | 54a | 94 | 50 | 4 | |

| Light mottling [1 - 10%] (score 2) | 44 | 4 | 44 | 50 | |

| Advanced mottling | 2 | 0 | 6 | 46 | |

| [11 - 25%] (score 3) | |||||

| Severe mottling and stunting | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| [26 - 40%] (score 4) | |||||

| Severe mottling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| [>40%] stunting and | |||||

| chlorosis (score 5) | |||||

| Fisher Exact test | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Friedman’s Chi-square test | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Viral severity score | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mace | Millennium | ||||

| Isolate | Isolate | ||||

| WSMV-br | WSMV-w | WSMV-br | WSMV-w | ||

| No symptoms (score 1) | 96a | 86 | 15 | 4 | |

| Some mottling [1 - 10%] | 2 | 7 | 28 | 10 | |

| (score 2) | |||||

| Advanced mottling | 2 | 4 | 33 | 48 | |

| [11 - 25%] (score 3) | |||||

| Severe mottling | 0 | 2 | 13 | 20 | |

| [26 - 40 %] and stunting | |||||

| (score 4) | |||||

| Severe mottling | 0 | 1 | 13 | 18 | |

| [>40%] stunting and | |||||

| chlorosis (score 5) | |||||

| Fisher Exact test | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Friedman’s Chi-square test | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Effect | Growth Chamber F statistic probability | Combined greenhouse F statistic probability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dfa | Plant height | Fresh weight | Dry weight | Plant Height | Fresh weight | Dry weight | |

| Cultivar | 1 | <.0001 | 0.8117 | 0.2534 | 0.0214 | 0.0022 | 0.0002 |

| Inoculum | 2 | <.0001 | 0.7151 | 0.0833 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Cultivar*Inoculum | 2 | 0.0053 | 0.3801 | 0.0489 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Cultivar | Compared treatments | Growth Chamber difference in |

Combined greenhouse difference in |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) |

P-value | Fresh weight (g) |

P-value | Dry weight (g) |

P-value | Plant height (cm) |

P-value | Fresh weight (g) |

P-value | Dry weight (g) |

P-value | ||

| Mace | WSMV-br vs Buffer | -1.33 | 0.0001 | -0.53 | 0.4639 | 0.05 | 0.0564 | -2.72 | <.0001 | -2.26 | 0.1241 | -0.21 | 0.5949 |

| Mace | WSMV-br vs WSMV-w | -0.46 | 0.3304 | 0.03 | 0.9975 | 0.05 | 0.0527 | -0.43 | 0.3318 | 1.44 | 0.4234 | 0.40 | 0.1464 |

| Mace | Buffer vs WSMV-w | 0.88 | 0.0191 | 0.56 | 0.4315 | 0.00 | 0.9996 | 2.29 | <.0001 | 3.71 | 0.0044 | 0.60 | 0.0132 |

| Millennium | WSMV-br vs Buffer | -2.17 | <.0001 | -0.02 | 0.9989 | -0.03 | 0.4593 | -3.45 | <.0001 | -5.47 | <.0001 | -0.75 | 0.0013 |

| Millennium | WSMV-br vs WSMV-w | 0.16 | 0.8754 | -0.36 | 0.7193 | 0.02 | 0.7061 | 1.93 | <.0001 | 9.23 | <.0001 | 1.85 | <.0001 |

| Millennium | Buffer vs WSMV-w | 2.33 | <.0001 | -0.34 | 0.7380 | 0.04 | 0.1202 | 5.38 | <.0001 | 14.7 | <.0001 | 2.60 | <.0001 |

| Greenhouse | Growth chamber | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ra | p-value | r | p-value | |

| Plant height (cm) | -0.56 | <0.0001 | -0.12 | 0.0449 |

| Fresh weight (g) | -0.40 | <0.0001 | -0.26 | <0.0001 |

| Dry weight (g) | -0.44 | <0.0001 | -0.16 | 0.1222 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).