1. Introduction

In cattle farms, the liquid feeding period for newborn calves is the period when calf losses are most common. During this period, calves need to consume colostrum, milk and milk powder feeds in a hygienic, technically appropriate, sufficient and regular manner. Feeding errors, inadequate/unbalanced feeding and poor hygiene conditions can lead to problems such as diarrhea [

1]. In newborn calves, the rumen is similar to the stomachs of animals that do not have a rumen function and do not chew the rumen, and they function like monogastric animals. The rumen begins as development and is usually not weaned or becomes fully functional later. During this transition, the calf

’s gastrointestinal system undergoes significant morphological and metabolic changes that allow the system to adapt to digesting and processing solid food. Therefore, the main goal during this critical period is to provide a balanced diet to newborn calves, properly support the digestive system and promote faster rumen development [

2].

One way to improve milk production efficiency in dairy cows is to promote effective treatment of rumen microbe nutrients and minimize energy and protein losses during fermentation. The use of feed additives such as monensin is a successful approach to improve rumen feed utilization by providing energy and protein supplements and increasing production rates in dairy cows, but the inclusion of monensin in animal diets has led to the diversification of resistant bacteria and their ability to grow through resistant bacterial strains. Therefore, recent efforts have been made to identify alternatives to antibiotics that could increase the production capacity of farm animals, and some plant extracts (PE) appear to be potential candidates [

3].

Diarrhea has been reported to cause 56% of morbidity and 32% of mortality in preweaned calves [

4]. This disease leads to significant welfare and health concerns such as dehydration, anorexia, decreased immune function and death, as well as reduced growth rates and increased risk of developing respiratory disease [

5]. In addition, diarrhea in pre-weaned calves can lead to long-term economic and production consequences such as poorer reproduction and lower milk production levels in their first lactation [

6,

7]. Beyond the productivity implications, there are concerns about the overuse of antimicrobials in cases of diarrhea. In particular, studies show that three-quarters of gastrointestinal diseases in calves are treated with antimicrobials; however, less than half of producers have designed a protocol to determine when to administer antimicrobial treatments [

4,

8]. In Türkiye, calf losses have also been the most common problem in recent years. It is estimated that there is an average of 15% of calves in Turkey each year. Considering that 8 million cows calve each year in Turkey, this is a very large figure for both enterprises and the national economy [

9].

The use of feed additives has been shown to increase the digestibility of feed in farm animals and reduce the negative effects of environmental conditions. It is well documented that it can lead to disruption of body balance and an increase in the prevalence of pathogenic microorganisms under stress conditions. As a result of these factors, the possibility of diarrhea increases due to the acceleration of intestinal movements [

10].

The productivity of dairy cattle supplemented with essential oils has been evaluated before, the results of these studies are not conclusive, but in some studies, productivity was not affected by phytogenic feed additives [

11,

12], while phytogenic feed additive supplementation increased feed use efficiency [

13,

14].

In light of this information, the aim of our study was to evaluate whether a phytogenic feed additive based on volatile oils such as thymol and cinnamaldehyde could be considered as a potential alternative to antimicrobials used as growth promoters and also to investigate its effect on blood values and degree of diarrhea.

2. Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Çukurova University Animal Experiments Local Ethics Committee with decision number 2 of the 5th meeting dated 20 May 2024. The experiment was carried out at the Çukurova University Faculty of Agriculture Research and Application Farm Dairy Cattle Farm (Adana, Türkiye) from October 2024 to December 2024.

2.1. Experimental Design and Treatments

A total of 40 newborn Holstein dairy calves were blocked by date of birth at the beginning of the study in a they were assigned to 1 of 2 treatment levels according to a 2 x 2 factorial experimental design (10 male + 10 female calves/treatment).

2.2. Calf Management

After parturition, calves were taken away from their dams immediately to prevent suckling and given 2 L of colostrum (>50 g IgG/L) within 2 h of being born, followed by another 2 L within 24 h of birth. Only the calves in block 4 were fed colostrum replacer, due to a shortage of high-quality colostrum at that time. Following colostrum feeding, calves were orally administered hyperimmune serum (Seradoll, Dollvet, Sanlıurfa, Türkiye) as a means of protecting them against Escherichia coli, and bovine rotavirus. To prevent infection, navels were disinfected by dipping them in a naval-dip solution (Vetericyn Super 7+, Terramycin*). Calves were housed in 1.1 m × 2.3 m individual pens bedded with dried straw. Calf pens were kept clean, and bedding was changed twice a day. Calves underwent dehorning via cauterization after receiving lidocaine at d 7. Ear tags were inserted after the animals reached 4 wk of age. During the trial, 11 calves (3 from Control female, 5 from Control male and 3 from T+C male) experienced scours and received treatment according to the established standard operating procedures at the Çukurova University Faculty of Agriculture Research and Application Farm Dairy Cattle Farm.

2.3. Feeding, Sampling, and Analysis of Feeds

The calves were given colostrum milked from their mothers half an hour after birth using a teat bucket. During the liquid feeding period from the 4th day until weaning, four liters of milk containing 3,78% CP and 3,71% fat was fed twice daily at 0600 h and 1800 h until d 56 of age. During the liquid feeding period from the 4th day until weaning, the calves were given starter feed, dry alfalfa hay (

Table 1) and water freely. Preparation of thymol and cinnamic aldehyde (T+C) (Macrovit Menoherb™ Adana, Türkiye) involved combining 6 g of powder with 3,9 L of milk, resulting in a total volume of approximately 4 L each feeding. The quantity of T+C provided to all calves was consistent and uniform throughout the study. Feed samples were ground through a 1-mm screen for nutritional analyses of absolute drymatter (method 930.15) [

15]; NDF(Ankom Fiber Analyzer A2000 with α-amylase and sodium sulfite; Ankom Technology, Fairpoint, NY; solutions as in Van Soest et al., [

16]; ADF (Ankom Fiber Analyzer A2000; Ankom Technology; method 973.18) [

17]; crude protein (method 990.03) [

15]; ether extract (method 2003.05) [

15]; ash (method 942.05) [

15].

2.4. Body Weight and Growth Measurements

Calf weights were first measured 24 h after birth, before inclusion in the study. Subsequently, their weights were recorded weekly until they reached 8 wk of age and again at the end of the study, using a digital scale (Uzay UZE-P 300, Türkiye) Average daily gain was calculated based on body weight (BW).

2.5. Blood Sampling and Analyses

Calf blood samples were taken via jugular venipuncture. Blood samples were collected from the calves 24 h after birth, before the inclusion in the study. Then samples were taken once a week until the age of 8 wk and at the end of the study, following the same schedule as BW. Two 10-mL evacuated tubes of blood were collected at 24 h. The first tube was used for whole blood collection without any additive, whereas the second tube included EDTA for plasma collection. The blood was centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. Biochemical analyses (Aspartate amino transferase (AST), Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), Cholesterol, Glucose, calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), Magnesium (Mg), Total Protein, Albumin, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were performed using commercial test kits using A-Validity brand autoanalyzer.

2.6. Fecal Sampling and Evaluation

Number of days scouring and severity of scouring of calves were recorded daily. Faecal scores and health observations were recorded at each feeding. Fluidity of faeces was scored on a four-point scale, with 1, normal – firm but not hard; 2, soft – does not hold form; 3, runny – spreads easily; 4, watery – devoid of solid matter [

18]. A faecal score of 2 was considered to be normal in our experiment. When calves developed faecal score >2, they were immediately assigned to antibiotic treatments. Antiobiotic treatments were administered to calves for the number of days that faecal scores were >2, plus two more days that faecal scores were ≤2. Incidences of faecal scores >2 occurred between days 5 and 56.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the number of calf diarrhea cases. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. MIXED fractions were separated to analyze data that were normally distributed or could be converted to normal. Two-way analysis of variance was performed in the study according to a 2x2 factorial experimental design in randomized plots grouped by treatment (control and treatment) and sex (male and female). Analysis was performed using the JAMOVI package program. Significance was considered at P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Calf Performance

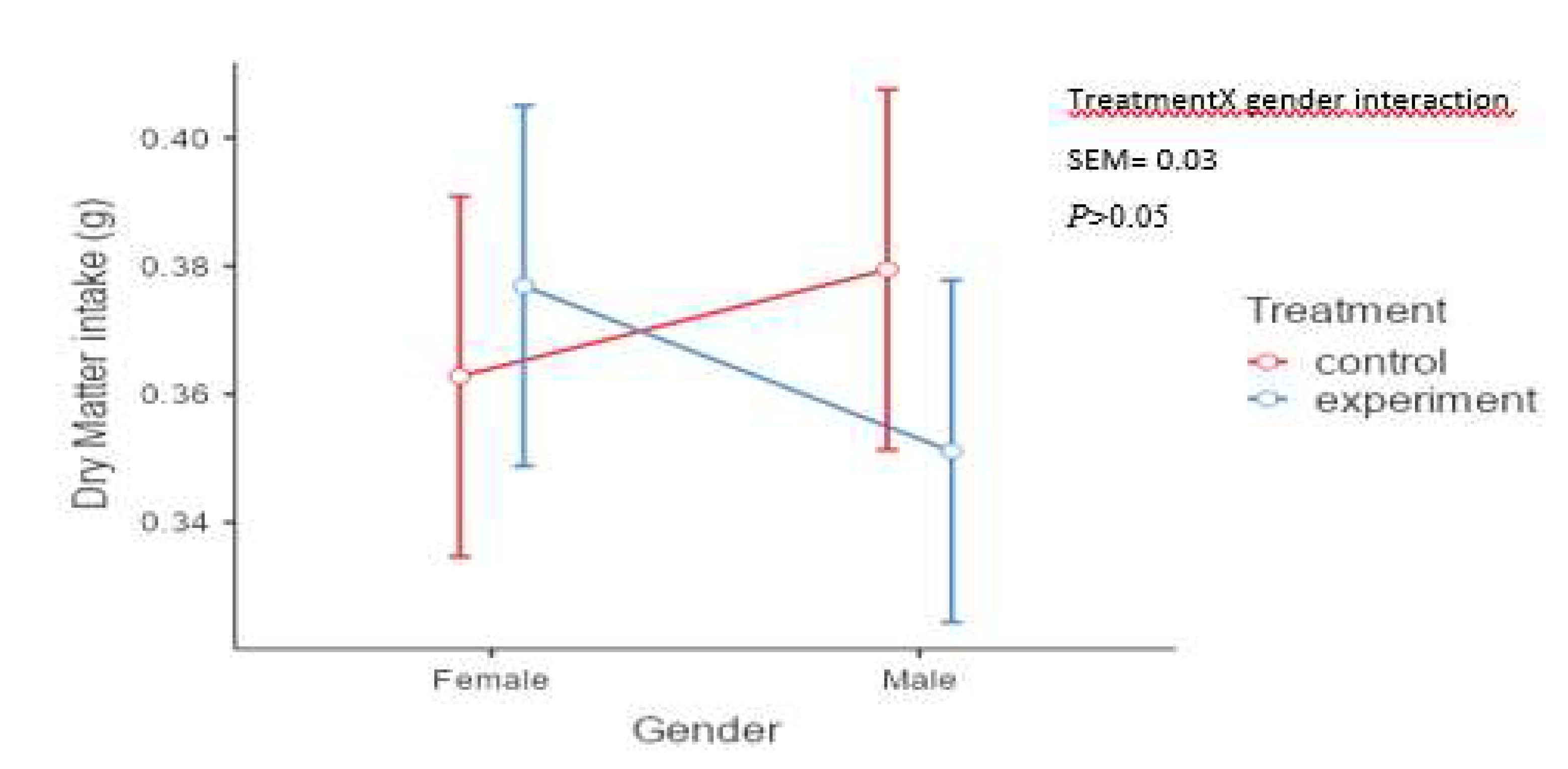

Drymatter intake averaged 0.36 kg/d and DMI were not different (

Figure 1) for Control (male and female) and T+C male female cows. Birth weights of females (n=18) ranged from 28.30 to 44.90 kg, while birth weights of males (n=19) ranged from 31.00 to 45.70 kg(P> 0.05) (

Table 2) among treatments (P> 0.05). Average daily gain and feed conversion ratio were similar (P> 0.05) in Control and T+C cows (

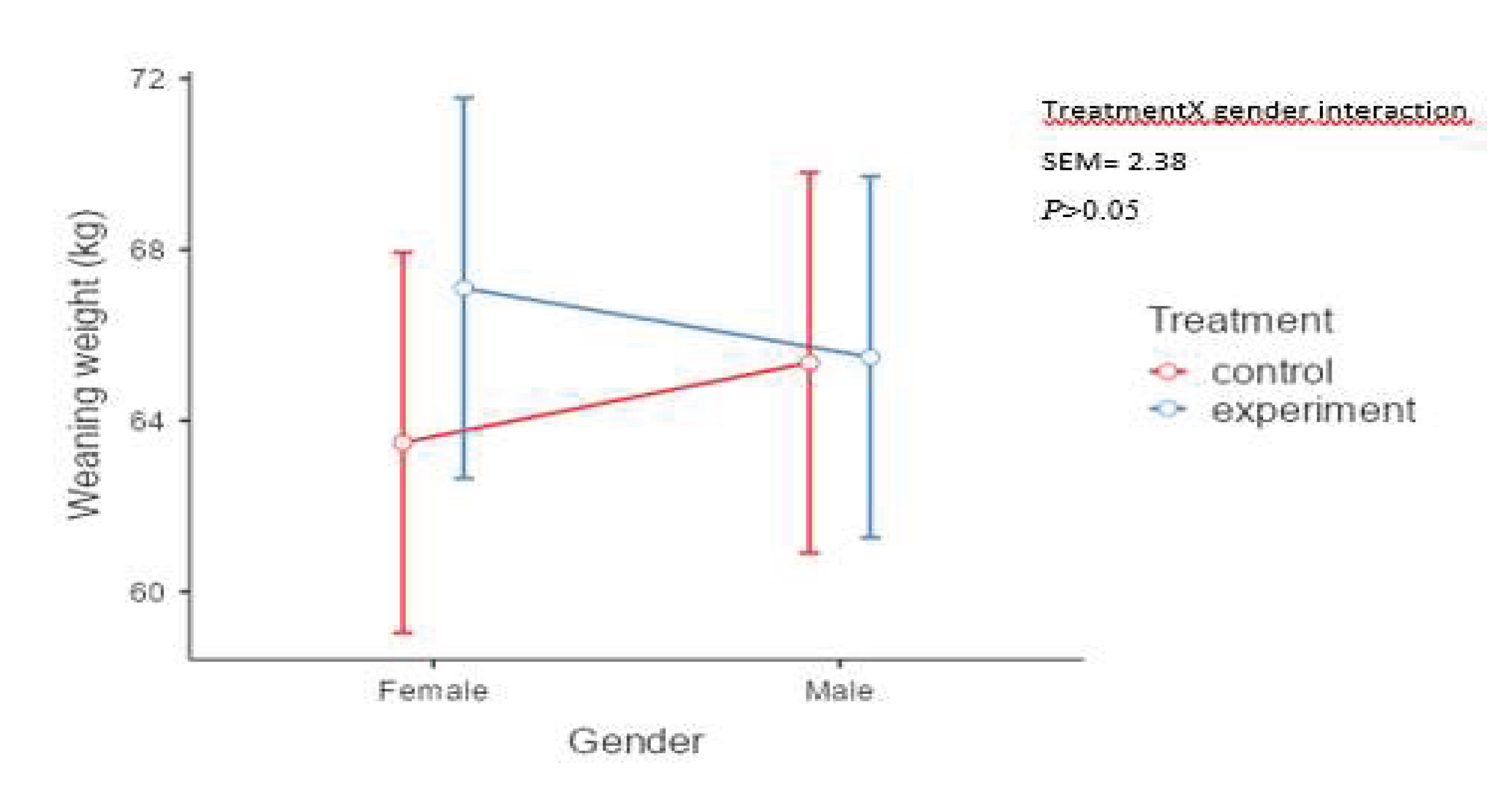

Table 2). There was no difference in respect to weaning weight (Figure 2) among treatments (P> 0.05). However, T+C application increased weaning weight in female calves.

3.2. Diarrhea Cases

These results are summarized in

Table 3 for cases with reproduction scores ≤ 1 and ≥ 2 in group experiments. 8 cases of diarrhea were diagnosed in the control group and 3 in the treatment group. Although there was a digital difference between the groups, it was determined that the distance between them and the treatment was independent of each other as a result of the analysis (p>0.05). In addition, sample addition was performed once a month and microbiological analysis was performed in the laboratory. As a result of fecal analysis, diarrhea, dehydration, lack of flavor and weight loss symptoms due to colibacillosis were shown. In cases of diarrhea, 73% of the treated cases were seen as control cases, while 23% of the diarrhea cases were seen in T+C application. While 50% of the female calves with fecal scores ≥ 2 and above had diarrhea, 42% of the male calves were found to be ≥ 2 and above.

3.3. Calf Blood Values

The results of blood sample analysis of experimental groups are given in

Table 4-5. The effect of gender on AST (Ul/l), GGT (Ul/l), glucose (mg/dl), Ca(mg/dl), Mg(mg/dl), TP (g/dl) and ALB (g/dl) and BUN(g/dl) at newborn status were found to be statistically insignificant (P>0.05). However, the effect of gender on phosphorus at birth and blood urea nitrogen at weaning was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05). The effect of treatment on blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in gender was found to be statistically significant(p=0.038). Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration increased with T+C supplementation during the weaning period in female calves, while it decreased in male calves. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) value in calves is an important indicator in terms of nutrition and metabolic health. Urea level reflects the protein balance in the diet and helps determine inadequate or excessive protein intake. It also indicates whether the liver and kidney functions are functioning healthily. During rumen development, excessive urea levels can disrupt the microflora balance and negatively affect digestion. Optimal blood urea levels (10-20 mg/dL) are critical for muscle development and growth performance, and the nutrition program should be reviewed in cases where these values are outside.

4. Discussion

4.1. Calf Performance

In the present study, T+C did not affect DMI, body weight, weaning weight, average daily gain and feed conversion ratio. Few studies [

12,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] have been investigated the effects of cinnamaldehyde and thymol on feed intake, average weight gain, milk production and compositon of dairy cows. Similarly, they found no differences in dry matter intake with the diet supplemented T+C.

However, Wall et al. [

3] reported an increase in DMI when a cinnamaldehyde/eugenol based encapsulated product was given at 350 mg/day in dairy cows, but a decrease in DMI was observed when the product was given at 600 mg/day. Cinnamaldehyde decreased somewhat with acetate/propionate cuts, either by increasing propionate, decreasing acetate, or both, depending on the fraction [

24], which may partly explain the detailed results discussed here. The increase in propionate may act as an energetic signal that decreases DMI [

25], but this theory awaits confirmation in lactating dairy cows where cinnamaldehyde is made.

The increased average daily gains detected by the available information are covered by previous studies [

26,

27]. The positive effect on ADG was recorded in female and male calves. Asghari et al. reported greater average daily gains in calves fed a starter diet supplemented with 300 mg/day of an organic oil mixture consisting of Thymus kotschyanus, Lavandula angustifolia, Salvia officinalis and Capparis spinosa, with the highest daily gain recorded 42 days after feeding organic oils [

27] . Cruz et al. reported that in 40 female calves to which phytogenic feed additives were applied, despite a difference in biochemical blood output, blood urea nitrogen was depleted, weaning live weight and feed utilization rate were increased, and there was no difference in diarrhea cases [

28] . Tepe at al. observed that although the growth performance of calves fed a commercial herbal mixture was better at 0–35 days [

18], The effect of essential oils on the main pathway of growth of suckling calves would have antimicrobial, antioxidant or anti-inflammatory effects [

14]. Thus, the change in growth performance may be due to the time required for new fats to affect growth performance or health problems that may arise at different stages of production.

The female calves in our study continued to grow in a statistically different way between weaning weight and the other experimental calves. When weaning interval and dry matter intake were weakly linked to the fit economic ranges, higher weaning live weight of breeding calves was weakly linked to IGF-1 activation.

4.2. Diarrhea Cases

Essential oil, as well as carvacrol and thymol, having antimicrobial properties, act by disrupting the bacterial cell membrane, which further affects pH homeostasis and equilibrium of inorganic ions, leading to release of membrane-associated material from the cells to the external medium [

29,

30]. Thymol and cinnamic aldehyde treatments were no significant differences were identified compared with the control group in our study. Reliance on treatment protocols and decision making by on-farm personnel using a more liberal therapeutic approach may have posed an issue, although it is possible that with a higher power, a difference in T+C treatments between treatment groups may have been detected. A larger sample size of animals may have offset the limitations posed by lack of protocol adherence, thus enhancing the differences between treatment groups and T+C usage. Although some studies claim that thyme use has no effect against diarrhea [

31,

32], found that thyme application reduces the coliform count in stool. The needed studies include the investigation of the activity of different supplementation levels of Thymol and cinnamic aldehyde and their efficacy against diarrhea.

The relationship between phytobiotic (phytogenic) compounds and diarrhea in calves has been a topic of considerable interest in recent years. Phytogenic compounds (e.g.,: cinnamaldehyde, thymol, carvacrol, eugenol, etc.) can significantly reduce the incidence of diarrhea by supporting intestinal health and natural additives of plant origin.

Phytogenic compounds can reduce the frequency and severity of diarrhea in calves thanks to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and digestive support properties.

Nora et al. [

33], observed in their study that when T+C was given with milk, diarrhea cases in the experimental group decreased from 30% to 10%. These results are parallel to our study.

Azizabadi et al. [

34], in their study with herbal volatile compounds, observed that diarrhea cases were 60% in the control group and 20% in the treatment group from weaning to weaning, and also found that ADG was higher in calves in the treatment group.

When we evaluate our study results, although there is no statistical difference between the groups, we see that the treatment group had shorter treatment times for diarrhea cases, and more calves with a score of ≤ 1 were observed. This suggests that its use in semi-intensive, extensive, and newly established dairy farms, rather than in fully equipped, full-time dairy farms, will be reflected in the reduction of diarrhea cases in calves and the shortening of treatment times, which will improve calves’ future productivity.

4.3. Calf Blood Values

Dietary supplementation of male and female cows with T+C decreased cholesterol concentrations (mg/dl), while AST (Ul/l) levels increased. No effect of the T+C application on GGT (Ul/l, glucose (mg/dl), Ca(mg/dl), Mg(mg/dl), TP (g/dl) and ALB (g/dl)was found. Thymol and cinnamic aldehyde application increased phosphorus levels in the blood of male cows, but had no effect on BUN levels. In contrast, it had no effect on phosphorus levels in the blood of female cows, but increased BUN levels.

While it was reported that [

20] the use of thyme and cinnamon essential oils in the feeding of calves had no effect on blood values, [

35] reported that thyme and garlic reduced blood serum total cholesterol levels.

Blood concentrations of liver enzymes such as AST and GGT are indicators of liver function and its tissue integrity. Elevated levels of these enzymes in the blood indicate damage to liver cells by trauma, inflamation, or cell wall lipid oxidation [

27]. GGT is an enzyme and biochemical parameter used to evaluate liver function and biliary tract status. GGT levels in newborn calves are closely related to colostrum intake. Colostrum contains high amounts of GGT and this enzyme increases in the calf’s bloodstream with colostrum consumption. Therefore, high GGT levels in the first days after birth are considered an indicator of adequate colostrum intake. Over time, as colostrum consumption decreases and the liver matures, GGT levels decrease and reach a normal balance [

36]. At the end of the weaning period, AST levels of male cows treated with T+C decreased, while GGT levels of female cows decreased.

Glucose did not change during the pre-weaning phase (

Table 4) and decreased during the post-weaning period on female and male calves (

Table 5). Taking into account that calves use glucose as a primary source of energy in the firsts weeks of age, these age-related changes are associated with changes in diet and rumen development [

37]. T+C application increased glucose levels in female calves during the weaning period. More research is needed on this topic as essential oils can increase insulin sensitivity [

26].

In the first days after birth, the high bioavailability of phosphorus through colostrum supports blood phosphorus levels [

38]. Initially low levels of estrogen and testosterone hormones begin to change over time, and these hormones may have indirect effects on the transport and storage of phosphorus in bones [

36]. Male calves generally grow faster than females [

38]. Therefore, male calves may need more phosphorus for bone development. In this study, T+C administration increased phosphorus levels in male cows at the end of the weaning period.

Tekippe et al. reported increased ruminal ammonia-N and BUN concentration in dairy cows supplemented with 500 g of oregano leave [

13] s. The higher BUN concentrations in female calves fed T+C supplementation might be due to the higher rates of protein degradation as a result of the higher protein intake and probably their better ruminal functioning. Hristov et al., Cinnamaldehyde was given to young ruminants and found a significant decrease in blood BUN levels [

39].

In their study conducted in Vakili et al., found that the addition of natural essential oils, in parallel with our study, did not have a significant difference in calf live weight gain, feed consumption and feed utilization amounts, and it did not affect the growth of calves negatively or positively, and there was no difference in glucose, triglyceride, cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), ALT and AST values [

20].

This suggests that flowers such as Thymol, cinnamaldehyde and carvacrol, as in our study, can inhibit proteolytic bacteria in the rumen and in this case reduce excess nitrogen release in the rumen. It can reduce rumen protein degradation (deamination) with reduced ammonia production, less urea is synthesized in the liver and a decrease in serum urea levels may occur as a result of this. nitrogen use efficiency is increased.

5. Conclusions

Phytogenic compound supplementation did not cause a significant difference in weaning weight, live weight gain, or feed utilization in female and male calves at weaning, but BUN levels decreased in the treatment group. When diarrhea scores were examined in the experimental groups, the frequency of diarrhea and duration of treatment were found to be lower in the treatment group compared to the control group. Based on these explanations, producers can utilize phytogenic compounds because they increase feed utilization and live weight at weaning, increase protein utilization efficiency due to the decrease in BUN levels, and support the digestive system and reduce diarrhea frequency. It would be beneficial to investigate the protein utilization efficiency of phytogenic compounds and clearly establish the relationship between calf growth parameters and protein utilization efficiency. Furthermore, based on the reduction in diarrhea incidence in calves supplemented with natural feed additives during calving, continued research once the calves reach productive age will reveal the effectiveness of natural feed additives.

Author Contributions

Methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, A.E.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, S.G,M.G.; software, validation, data curation, A.E.,C.A.O.; conceptualization, writing—review and editing, Ş.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the Scientific Research Unit of Cukurova University in Adana, Türkiye, under project number FLO-2024-16919.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by Cukurova University Animal Experiments Local Ethics Committee with decision number “2” on “28.05.2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the authors for their dedicated efforts in fieldwork, sample collection, laboratory and data analysis, and manuscript writing. I would also like to thank MAKROVIT (Konya, Turkey) for their support with laboratory infrastructure and product supply throughout the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DL |

Diarrhea Levels |

| CTRL |

Control diet |

| DMI |

DMI, |

| ADG |

Average Daily Gain, |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| GGT |

Gamma Glutamyl Transferase |

| BUN |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| T+C |

Thymol and Cinnamic aldehyde |

| ADF |

Acid Detergent Fiber, |

| NDF |

Neutral Detergent Fiber, |

| ME |

Metabolic Energy |

References

- McGuirk, SM. , 2003. Solving calf morbidity and mortality problems. In American Association of Bovine Practitioners, 36th Annual Conference.

- Islam, T. , Rahman, M. A., Valentine, L. J. and Erickson, P. S., 2025. Incremental nicotinic acid supplementation to preweaning dairy calves: Effects on growth, blood metabolites, purine derivatives, and indirect rumen development. J. Dairy Sci. 108:7011–7022.

- Wall, E.H. , Doane,P.H., Donkin, S.S., Bravo,D. (2014). 9: The effects of supplementation with a blend of cinnamaldehyde and eugenol on feed intake and milk production of dairy cows, Journal of Dairy Science,97, 5709; :9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urie, N. J., J. E. Lombard, C. B. Shivley, C. A. Kopral, A. E. Adams, T. J. Earleywine, J. D. Olson, and F. B. Garry. 2018. Preweaned heifer management on US dairy operations: Part V. Factors associated with morbidity and mortality in preweaned dairy heifer calves. J. Dairy Sci. 101:9229–9244. https: / / doi.org/ 10.3168/ jds.2017 -14019.

- Schinwald, M., K. Creutzinger, A. Keunen, C. B. Winder, D. Haley, and D. L. Renaud. 2022. Predictors of diarrhea, mortality, and weight gain in male dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 105:5296–5309.

- Bartels, C.J.M. , Holzhauer, M., Jorritsma, R., Swart, W.A.J.M., Lam, T.J.G.M., 2010. Prevalence, prediction and risk factors of enteropathogens in normal and non-normal faeces of young Dutch dairy calves. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 93 (2010) 162–169.

- Abuelo, A., F. Cullens, and J. L. Brester. 2021. Effect of preweaning disease on the reproductive performance and first-lactation milk production of heifers in a large dairy herd. J. Dairy Sci. 104:7008– 7017. https: / / doi.org/ 10.3168/ jds.2020 -19791.

- Uyama, T., D. F. Kelton, E. I. Morrison, E. de Jong, K. D. McCubbin, H. W. Barkema, S. Dufour, J. Sanchez, L. C. Heider, S. J. LeBlanc, C. B. Winder, J. T. McClure, and D. L. Renaud. 2022. Cross-sectional study of antimicrobial use and treatment decision for preweaning Canadian dairy calves. JDS Commun. https: / / doi.org/ 10.3168/ jdsc.2021 -0161.

- Göncü, S. , Gökçe G. 2021. The Effects of Calf Weanıng on Holsteın Male Calves Blood Parameters. Iğdır Internatıonal Applıed Scıences Congress, Türkiye, 14 April.

- Görgülü, M. , Siuta, A., Ongel, E., Yurtseven, S., Kutlu, H.R., 2003. Effect of probiotic on growing performance and health of calves. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 6(7): 651-654.

- Benchaar, C. , 2016. Diet supplementation with cinnamon oil, cinnamaldehyde, or monensin does not reduce enteric methane production of dairy cows. Animal 10, 418–425. [CrossRef]

- Benchaar, C. , 2021. Diet supplementation with thyme oil and its main component thymol failed to favorably alter rumen fermentation, improve nutrient utilization, or enhance milk production in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 104, 324–336. [CrossRef]

- Tekippe, J.A. , Hristov, A.N., Heyler, K.S., Cassidy, T.W., Zheljazkov, V.D., Ferreira, J.F. S., Karnati, S.K., Varga, G.A., 2011. Rumen fermentation and production effects of Origanum vulgare L. leaves in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 94, 5065–5079. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J. , Wall, E.H., Bravo, D.M., Hristov, A.N., 2017. Host-mediated effects of phytonutrients in ruminants: a review. J. Dairy Sci. 100, 5974–5983.

- AOAC International. 2016. Official Methods of Analysis. 20th ed.

- Van Soest, P. J., J. B. Robertson, and B. A. Lewis. 1991. Methods of dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74:3583–3597. https: / / doi.org/ 10.3168/ jds.S0022 -0302(91)78551 -2.

- AOAC. 1998. Official Methods of Analysis.16th ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Arlington, VA.

- Tepe B, Eminagaoglu O, Akpulat HA and Aydin E(2007). Antioxidant potentials and rosmarinic acidlevels of the methanolic extracts of Salvia verticillata(L.) subsp. verticillata and S. verticillata (L.) subsp.amasiaca (Freyn & Bornm.) Bornm. Food Chem. 9: 100.

- Greathead, H.M.R. , Forbes, J.M., Beaumont, D., Kamel, C. 2000. The effect of a formulation of natural essential oils used as an additive with a milk replacer and a compound feed on the feed efficiency of calves. 6: British Society of Animal Sciences, Annual Winter Meeting, ISBN: 0906562325 p, 0906. [Google Scholar]

- Vakili, A.R. , Khorrami, B., Mesgaran, M.D., Parand, E. 2013. The effects of thyme and cinnamon essential oils on performance,rumen fermentation and blood metabolites in holstein calves consuming high concentrate diet, Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 9: 26(7).

- Benchaar, C. , McAllister, T. A. and Chouinard, P. Y., 2008. Digestion, Ruminal Fermentation, Ciliate Protozoal Populations, and Milk Production from Dairy Cows Fed Cinnamaldehyde, Quebracho Condensed Tannin, or Yucca schidigera Saponin Extracts. J. Dairy Sci. 4: 91, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaar, C. , 2020. Feeding oregano oil and its main component carvacrol does not affect ruminal fermentation, nutrient utilization, methane emissions, milk production, or milk fatty acid composition of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 103, 1516–1527. [CrossRef]

- Cantet, J, M., Yu, Z., Tucker, H.A., Ríus, A.G. (2023). 2721. [CrossRef]

- Calsamiglia, S. , Busquet, M., Cardozo, P.W., Castillejos, L., Ferret, A., 2007. Invited review: essential oils as modifiers of rumen microbial fermentation. J. Dairy Sci. 90, 2580–2595. [CrossRef]

- Oba, M. , Allen, M.S., 2003. Intraruminal infusion of propionate alters feeding behavior and decreases energy intake of lactating dairy cows. J. Nutr. 133 (4), c–1099.

- Jeshari M, Riasi A, Mahdavi AH, Khorvash M, Ahmadi F. Effect of essential oils and distillation residues blends on growth performance and blood metabolites of Holstein calves weaned gradually or abruptly. Livest Sci. 2016; 185: 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Asghari, M. , Abdi-Benemar, H., Maheri-Sis,N., Salamatdoust-Nobar, R., Salem A. Z.M., Zamanloo, M., Anele, U. Y. 2021. 1149; ,54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, V. , Martínez, M. L. A., Hernández-García, G. D., Espinosa-Ayala, P. A., Díaz-Galván, E., Vázquez-Silva, C., Torre-Hernández, M. E., 2025. Growth Performance, Health Parameters, and Blood Metabolites of Dairy Calves Supplemented with a Polyherbal Phytogenic Additive. Animals, 15(4), 576.

- Helander, I. M., H. L. Alakomi, K. Latva-Kala, T. Mattila-Sandholm, I. Pol, E. J. Smid, L. G. M. Gorris, and A. Von Wright, 1998: Characterization of the action of selected essential oil components on Gram-negative bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 3590– 3595.

- Lambert, R. J. W., P. N. Skandamis, P. J. Coote, and G.-J. E. Nychas, 2001: A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91, 453–462.

- Bampidis, V. A. , Christodoulou, V., Florou-Paneri, P. and Christaki, E., 2006. Effect of Dried Oregano Leaves Versus Neomycin in Treating Newborn Calves with Colibacillosis. J. Vet. Med. A 53, 154–156 (2006).

- Carter HSM, Steele MA, Costa JHC, Renaud DL. Evaluating the effectiveness of colostrum as a therapy for diarrhea in preweaned calves. J Dairy Sci. 2022 Nov;105(12):9982-9994. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nora, L. , Marcon C., Deolindo G. L., Signor M. H., Muniz A. L., Bajay M. M., Copetti P. M., Bissacotti B. F., Morsch V. M. & da Silva A. S. (2024). “The Effects of a Blend of Essential Oils in the Milk of Suckling Calves on Performance, Immune and Antioxidant Systems, and Intestinal Microbiota. 3: Animals, 14(24), 3555. [Google Scholar]

- Azizabadi, H.J. , Hiwa Baraz, Naghme Bagheri & Morteza Hosseini Ghaffari (2022). “Effects of a mixture of phytobiotic rich herbal extracts on growth performance, blood metabolites, rumen fermentation, and bacterial population of dairy calves. 5: Journal of Dairy Science, 105(6), 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, H. B. , Erkek, R., Özdoğan, M., Mert, S., 2013. Buzağı Beslemede Doğal Yem Katkı Maddelerinin Kullanımı. Hayvansal Üretim 54(2): 36-42, 2013.

- Göncü, S. , Doğan, S., Erez, İ., Dinç, E.Y., Fırat, İ.V., Görgülü, M.,2025. Blood Parameters of Male and Female Holstein Calves at Birth and Weaning in Mediterranean Climate Conditions. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LS, Bittar CMM. Performance and plasma metabolites of dairy calves fed starter containing sodium butyrate, calcium propionate or sodium monensin. animal. 2011; 5: 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Piccione G, Casella IS, Pennisi P, et al. Monitoring of physiological and blood parameters during perinatal and neonatal period in calves.Veteri¬nary Medicine. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2010;62(1).

- Hristov, A. N.; Lee, C.; Cassidy, T. W.; Heyler, K. S.; Tekippe, J. A.; Varga, G. A.; Corl, B.; Brandt, R. C. (2013).”Effect of Origanum vulgare L. leaves on rumen fermentation, production, and milk fatty acid composition in lactating dairy cows. 1: Journal of Dairy Science, 96(2), 1189. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).