Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- The publication must be a peer-reviewed journal article (including original research, short communications, or data papers);

- (ii)

- The study must include at least one country within the PICTs;

- (iii)

- The article must be written in English.

3. Results and Discussions

- (iv)

- Quantitative gap – There is a limited volume of published research on FGR in the region, reflecting an overall scarcity of scholarly attention.

- (v)

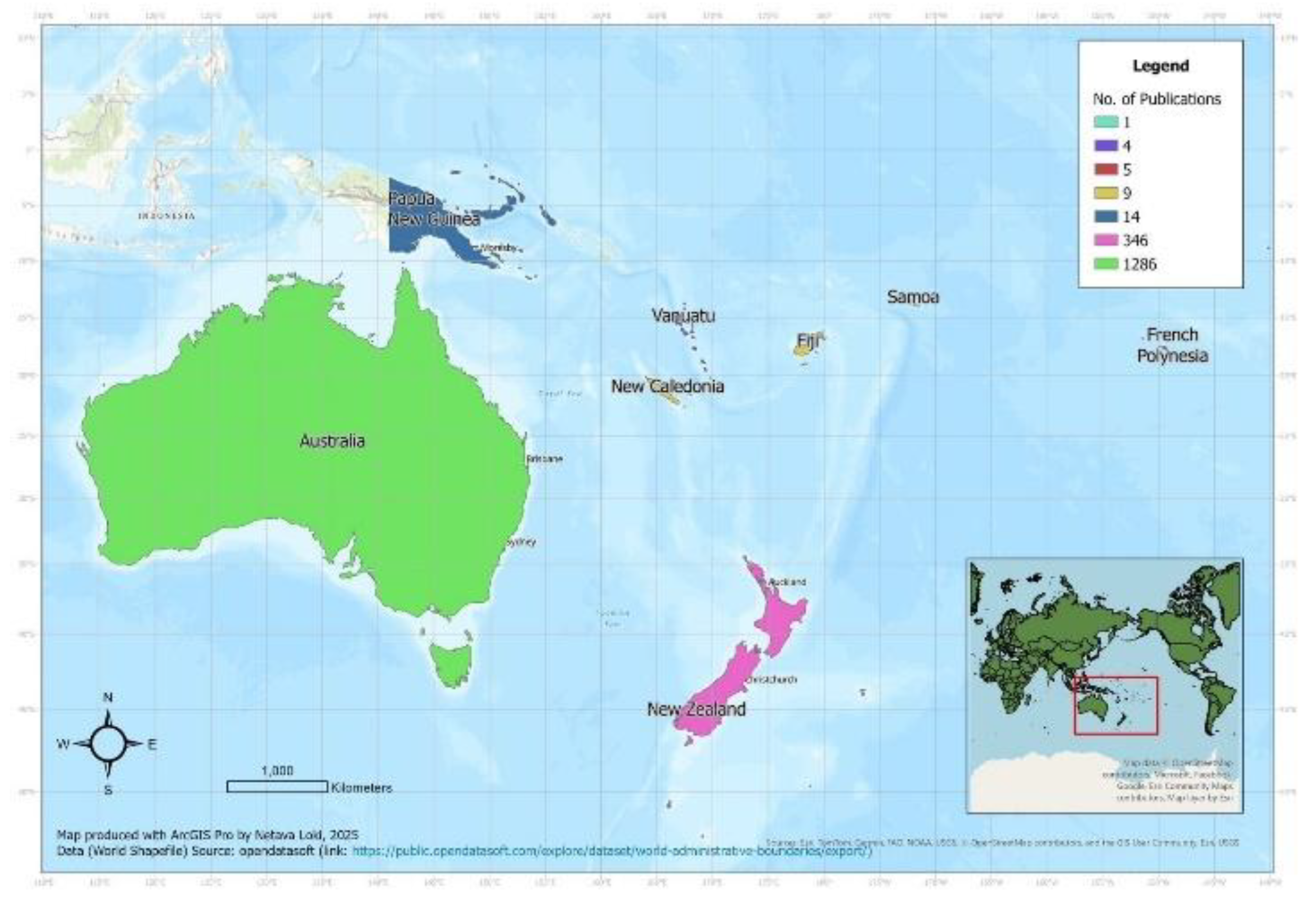

- Geographic gap – Existing studies are unevenly distributed across PICTs, with certain countries and subregions significantly underrepresented in the literature.

- (vi)

- Temporal gap – Few studies have focussed on long-term monitoring of FGR, highlighting the need for sustained research efforts to inform comprehensive conservation and management strategies.

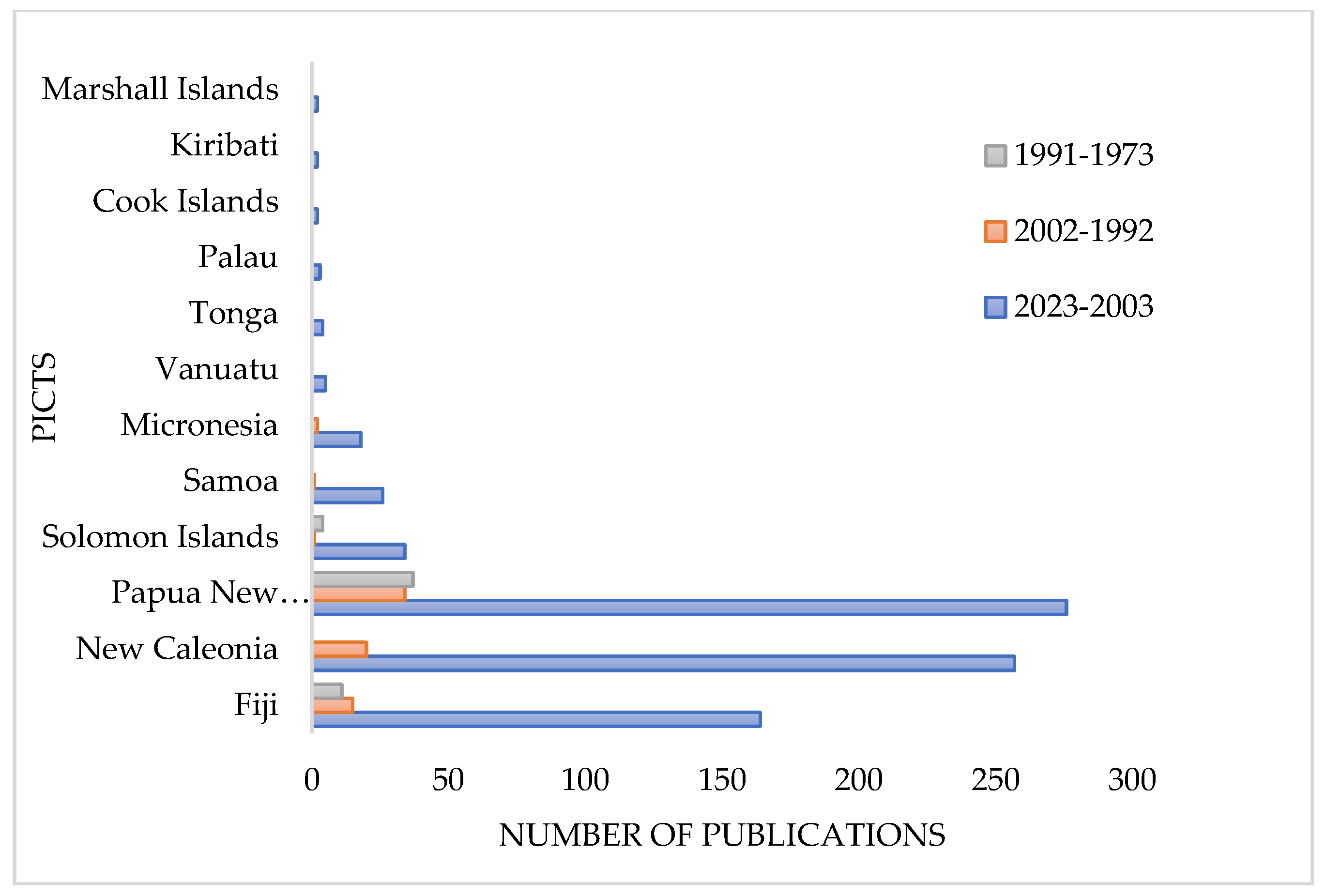

3.1. Bibliometric Insights into FGR Research in PICTs

3.1. Geographical representation of FGR studies

| PICTs | FGR studied | Habitat | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji |

Cycas seemannii Santulum yasi |

Native forests Native forests |

Starch-gel electrophoresis revealed low intra- population diversity and high inter- population differentiation Despite low diversity in remnant stands, the species retains substantial genetic variation |

[57] [62] |

| Micronesia | Campnosperma brevipetiolata | Native forests | Enzyme assay protocols revealed a west to east decline in genetic variation across the Indo-Malayan source region | [63] |

| New Caledonia |

Diospros spp. Santalum austrocaledonicum Pycnandra spp. Coffea spp. Araucaria nemorosa |

Native forests Native forests Native forests Plantations Plantations |

Genetic diversity in Diospyros stems from gradual accumulation and rapid radiations into four lineages Chloroplast microsatellite analyses revealed overall heterozygosity, with variation among islands Three new species were described using nuclear DNA data from ETS, ITS, and RPB2 regions Inter-specific hybridization was detected, with one population showing high genetic diversity based on 26 microsatellites markers using multi-locus approach Nuclear microsatellite (nSSR) analysis revealed genetic bottle neck and elevated inbreeding in nursery stock compared to seedlings and adult populations |

[54] [60] [64] [65] [61] |

| Papua New Guinea |

Ixora margaretae Ficus spp. Eucalyptus pellita |

Native forests Native forests Plantations |

Assisted regeneration with controlled variability will be critical to conserving species biodiversity, as indicated by SSR fingerprinting Restricted elevation ranges in multiple Ficus species constrain gene flow SNP analysis indicates Queensland as the origin of E. pellita, with high genetic diversity |

[66] [67] [68] |

| Samoa | Terminalia richii and Manilkara samoensis | Native forests | Complimentary in situ and ex situ conservation strategies are essential for the species | [58] |

| Vanuatu | Carpoxylum macrospermum | Native forests | RAPD analysis revealed low genetic variation within the existing population | [59] |

| Hawaiian Islands, Marquesas Islands, Society Islands, and New Caledonia | Miconia calvescens | Tropical islands | Microsatellites and inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers revealed genetic variation within and among populations | [69] |

| Fiji, Samoa, and Hawaiian Islands | Cyrtandra spp. | Native forests | Co-existing Cyrtandra species show closer phylogenetic and phenotypic clustering within island and site communities | [70] |

3.3. Temporal Gap in FGR Research Across PICTs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgements

Declaration of competing interest

Abbreviations

| FGR | Forest Genetic Resources |

| ACIAR | Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research |

| CePaCT | Centre for the Pacific Crops and Trees |

| CSIRO | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FAO | UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization |

| ETS | E26 transformation-specific family of transcription factors |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IPBES | Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services |

| ISSR | Inter-simple sequence repeat |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer |

| nSSR | Nuclear microsatellite |

| PICTs | Pacific Island Countries and Territories |

| PIRT | Pacific Islands Roundtable for Nature Conservation |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| RAPD | Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA |

| RPB2 | RNA polymerase II subunit B |

| SPRIG | South Pacific Regional Initiative on Forest genetic resources |

| SSR | Simple Sequence Repeat |

| WoS | ISI Web of Science |

References

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Gill, P.R.; Hoffman, M.; Pilgrim, J.; Brooks, T.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Lamoreux, J.; Fonseca, G. Hotspots revisited: earths biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions. Cemex 2004, 392. [Google Scholar]

- Keppel, G.; Lowe AJ,Possingham, H. P. Changing perspectives on the biogeography of the tropical South Pacific: Influences of dispersal, vicariance and extinction. Journal of Biogeography 2009, 36, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kier, G.; Kreft, H.; Lee TM, Jetz W, Ibisch PL, Nowicki C, Mutke J,Barthlott, W. A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 9322–9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Matthews, T.J. (2023). Island biogeography: Geo-environmental dynamics, ecology, evolution, human impact, and conservation. Oxford University Press.

- Frankham, R. Inbreeding and extinction: Island populations. Conservation Biology 1998, 12, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Dombois, D. Pacific Island forests: Successionally impoverished and now threatened to be overgrown by aliens? Pacific Science 2008, 62, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, R.T.; Watson, J.E.; Lundquist, C.J.; Venter, O.; Hughes, L.; Johnston, E.; Atherton, J.; Gawel, M.; Keith, D.A.; Mackey, B.G. Major conservation policy issues for biodiversity in Oceania. Conservation Biology 2009, 23, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woinarski, J. Biodiversity conservation in tropical forest landscapes of Oceania. Biological Conservation 2010, 143, 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, D.W. (2006). Extinction and biogeography of tropical Pacific birds. University of Chicago Press.

- Barnett, J.; Campbell, J. (2010). Climate change and small island states: Power, knowledge and the South Pacific (pp. 1–218). London: Earthscan Ltd;03/31. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.-M.; Béné; C; Bennett, G. ; Boso, D.; Hilly, Z.; Paul, C.; Posala, R.; Sibiti, S.; Andrew, N. Vulnerability and resilience of remote rural communities to shocks and global changes: Empirical analysis from Solomon Islands. Global Environmental Change 2011, 21, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtling, R.; Robison, T.; McKeand, S.; Rousseau, R.; Allen, H.; Goldfarb, B. (2004). The role of genetics and tree improvement in southern forest productivity. In Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS (Vol. 75, pp. 97–108). National Technical Information Service.

- Thaman, R.R. A matter of survival: Pacific Islands vital biodiversity, agricultural biodiversity and ethno-biodiversity heritage. Pacific Ecologist 2008, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, L.; Doran, J.; Clarke, B. 2018. Trees for life in Oceania: conservation and utilisation of genetic diversity.

- Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A. Ethnobotany of ocean-going canoes in Lau, Fiji. Economic Botany 1987, 41, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPREP 2007. Forest and tree genetic resource conservation, management and sustainable use in Pacific Island Countries and Territories SPREP PROE - Virtual Library: Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme; 2007.

- Schmitt, C.B.; Burgess, N.D.; Coad, L.; Belokurov, A.; Besançon, C.; Boisrobert, L.; Campbell, A.; Fish, L.; Gliddon, D.; Humphries, K. Global analysis of the protection status of the world’s forests. Biological Conservation 2009, 142, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, R.; Venter, M.; Aragon-Osejo, J.; González-Del-Pliego, P.; Hansen AJ, Watson JE,Venter, O. Tropical forests are home to over half of the world's vertebrate species. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2022, 20, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Hopa, D.; Wapot, S. 2016. The contested forests: searching for new visions for forestry in Melanesia. Port Villa, Vanuatu: Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) Secretariat through the Pacific Integration Technical Assistance Project (PITAP) which is funded by the European Union under the 10th European Development Fund (EDF).

- OECD 2012. OECD environmental outlook to 2050: the consequences of inaction. Kitamori K., Manders T., Dellink R., Tabeau A., editors: OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/41/4/50523645.pdf.

- Corlew, L.K. 2012. The cultural impacts of climate change: sense of place and sense of community in Tuvalu, a country threatened by sea level rise. Honolulu, Hawaii: [Doctoral dissertation, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa].

- André; T; Lemes MR, Grogan J,Gribel, R. Post-logging loss of genetic diversity in a mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla King, Meliaceae) population in Brazilian Amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management 2008, 255, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lacerda, A.E.B.; Nimmo, E.R.; Sebbenn, A.M. Modeling the long-term impacts of logging on genetic diversity and demography of Hymenaea courbaril. Forest Science 2013, 59, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledig, F.T. Conservation strategies for forest gene resources. Forest Ecology and Management 1986, 14, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.L.; Hawksworth, D.L. 1994. Biodiversity: measurement and estimation. Preface. The Royal Society London. p. 5-12. [CrossRef]

- BLAG - expert group. 2004. Concept on the genetic monitoring for forest tree species in the Federal Republic of Germany. 2004. https://www.academia.edu/download/41909092/Criteria_and_Indicators_for_Sustainable_20160202-12868-kla5we.pdf.

- Aravanopoulos, F.A.; Tollefsrud, M.M.; Graudal, L.; Koskela, J.; Kätzel, R.; Soto, A.; Nagy, L.; Pilipovic, A.; Zhelev, P.; Bozic, G.; Bozzano, M. (2015). Development of genetic monitoring methods for genetic conservation units of forest trees in Europe. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN).

- Luoma-Aho, T. 2004. Forest genetic resources conservation and management. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Forest Genetic Resources Programme (APFORGEN) Inception Workshop. Kepong, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Bioversity International; 2004.

- Westergren, M.; Fussi, B.; Konnert, M.; Aravanopoulos, F.; Kraigher, H. 2015. LIFEGENMON-LIFE for European forest genetic monitoring system: a LIFE+ fund for development of a system for forest genetic monitoring. XIV World Forestry Congress; 2015; Durban, South Africa.

- Newton, P.; Castle, S.; Kinzer, A.; Miller, D.; Oldekop, J.; Linhares-Juvenal, T.; Pina, L.; Madrid, M.; de Lamo Rodriguez, J. 2022. The number of forest-and tree-proximate people: a new methodology and global estimates. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Taylor, M.; McGregor, A.; Dawson, B. 2016. Vulnerability of Pacific Island agriculture and forestry to climate change. Noumea, French Calendonia: Pacific Community.

- McGinley, K.A.; Robertson, G.C.; Friday, K.S. Examining the sustainability of tropical island forests: Advances and challenges in measurement, monitoring, and reporting in the US Caribbean and Pacific. Forests 2019, 10, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, M. ; Renaud FG, Sudmeier-Rieux K, Nehren, U. 2016. Defining new pathways for ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction and adaptation in the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction and adaptation in practice: Springer. 553-591. [CrossRef]

- Padolina, C. An overview of forest genetic resource conservation and management in the Pacific. Acta Horticulturae 2007, 757, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Jupiter, S. 2010. Law, custom and community-based natural resource management in Kubulau District (Fiji). Environmental Conservation; 37: 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Risna, R.; Prasetyo, L.; Lughadha, E.; Aidi, M.; Buchori, D.; Latifah, D. Forest resilience research using remote sensing and GIS – A systematic literature review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2023, 1266, 012086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M.; Sanderson, D.; Osborne, K.; Deo, R.; Faith, J.; Ride, A. Area-based approaches and urban recovery in the Pacific: lessons from Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Environment & Urbanization 2022, 34, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkoong, G.; Boyle, T.; Gregorius, H.-R.; Joly, H.; Savolainen, O.; Ratnam, W.; Young, A. 1996. Testing criteria and indicators for assessing the sustainability of forest management: genetic criteria and indicators (Vol. 10): CIFOR Bogor.

- Namkoong, G.; Boyle, T.; El-Kassaby YA, Palmberg-Lerche C, Eriksson G, Gregorius H, Joly H, Kremer A, Savolainen O, Wickneswari, R. 2002. Criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management: assessment and monitoring of genetic variation. Rome, Italy: Forestry Department (working paper), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Munim, Z.H.; Dushenko, M.; Jimenez, V.J.; Shakil, M.H.; Imset, M. Big data and artificial intelligence in the maritime industry: a bibliometric review and future research directions. Maritime Policy & Management 2020, 47, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olisah, C.; Adams, J.B. Analysing 70 years of research output on South African estuaries using bibliometric indicators. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 2021, 252, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The state of the world’s forest genetic resources. Commission on genetic resources for food and agriculture food and agriculture organization of the United Nations, Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/i3825e/i3825e.pdf.

- Thomas, A.; Baptiste, A.; Martyr, R.; Pringle, P.; Rhiney, K. Climate Change and Small Island Developing States. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaidjian, E., Robinson, S.-a. 2022. Reviewing the nature and pitfalls of multilateral adaptation finance for small island developing states. Climate Risk Management; 36:100432. [CrossRef]

- Siwatibau, S., editor Forests, trees and human needs in Pacific communities. Proceedings of the 12th World Forestry Congress 2003; Quebec, Canada. https://www.fao.org/4/XII/MS1-E.htm.

- Hwang, K. 2013. Effects of the language barrier on processes and performance of international scientific collaboration, collaborators’ participation, organizational integrity, and interorganizational relationships. Science Communication; 35:3-31. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.; Scherl, L.; Phan, H.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; Lavey, W.; Byakagaba, P.; Idrobo CJ, Chenet A, Bennett N, Mansourian S, Rosado F, Dawson N, Coolsaet B, Rosado-May, F. The role of indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecology and Society 2021, 26, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, F.; Koskela, J.; Hubert, J.; Kraigher, H.; Longauer, R.; Olrik DC, Schüler S, Bozzano M, Alizoti P,Bakys, R. Dynamic conservation of forest genetic resources in 33 European countries. Conservation Biology 2013, 27, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalonen, R.; Choo, K.; Hong, L.; Sim, H. (2009). Forest genetic resources conservation and management: Status in seven South and Southeast Asian countries. FRIM, Bioversity International and APAFRI.

- Uribe-Toril, J. ; Ruiz-Real JL, Haba-Osca J,de Pablo Valenciano, J. Forests’ first decade: A bibliometric analysis overview. Forests 2019, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravanopoulos, F.A. Conservation and monitoring of tree genetic resources in temperate forests. Current Forestry Reports 2016, 2, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupiter, S.; Mangubhai, S.; Kingsford, R.T. Conservation of biodiversity in the Pacific Islands of Oceania: Challenges and opportunities. Pacific Conservation Biology 2014, 20, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangjai, S.; Samuel, R.; Munzinger, J.; Forest, F.; Wallnöfer, B.; Barfuss MH, Fischer G,Chase, M. W. A multi-locus plastid phylogenetic analysis of the pantropical genus Diospyros (Ebenaceae), with an emphasis on the radiation and biogeographic origins of the New Caledonian endemic species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2009, 52, 602–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, R.M. C. , Silva, L., Olangua-Corral, M., Roxo, G., Resendes, R., Herrezuelo, A.G., Bettencourt, J., Freitas, C., Pereira, D., Moura, M. Integrating in situ strategies and molecular genetics for the conservation of the endangered Azorean endemic plant Lotus azoricus. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouichi, S.; Ghanem ME, Amri, M. In-situ and ex-situ conservation priorities and distribution of lentil wild relatives under climate change: A modelling approach. Journal of Applied Ecology 2025, 62, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Lee, S.-W.; Hodgskiss, P. Evidence for long isolation among populations of a Pacific cycad: Genetic diversity and differentiation in Cycas seemannii A. Br. (Cycadaceae). Journal of Heredity 2002, 93, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouli, T.; Alatimu, T.; Thomson, L. Conserving the Pacific Island’s unique trees: Terminalia richii and Manilkara samoensis in Samoa. International Forestry Review 2002, 4, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowe, J.L.; Benzie, J.; Ballment, E. Ecology and genetics of Carpoxylon macrospermum H. Wendl. & Drude (Arecaceae), an endangered palm from Vanuatu. Biological Conservation 1997, 79, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottin, L.; Tassin, J.; Nasi, R.; Bouvet, J.-M. Molecular, quantitative and abiotic variables for the delineation of evolutionary significant units: Case of sandalwood (Santalum austrocaledonicum Vieillard) in New Caledonia. Conservation Genetics 2007, 8, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, C.J.; Ennos, R.A.; Jaffré; T; Gardner, M. ; Hollingsworth, P.M. Cryptic genetic bottlenecks during restoration of an endangered tropical conifer. Biological Conservation 2008, 141, 1953–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolatolu, W.; Clarke, B.; Likiafu, H.; Mateboto, J.; Thomson, L. (2022). Domestication and breeding of sandalwood in Fiji and Tonga. CABI Databases: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/fst-2016-158.

- Sheely, D.L.; Meagher, T.R. Genetic diversity in Micronesian island populations of the tropical tree Campnosperma brevipetiolata (Anacardiaceae). American Journal of Botany 1996, 83, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, U.; Munzinger, J.; Nylinder, S. ; Gâteblé; G The largest endemic genus in New Caledonia grows: Three new species of Pycnandra (Sapotaceae) restricted to ultramafic substrate with updated subgeneric keys. Australian Systematic Botany 2021, 34, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.; Batti, A.; Le Pierrès, D.; Campa, C.; Hamon, S.; De Kochko, A.; Hamon, P.; Huynh, F.; Despinoy, M.; Poncet, V. Favourable habitats for Coffea inter-specific hybridization in central New Caledonia: Combined genetic and spatial analyses. Journal of Applied Ecology 2010, 47, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaegen, D.; Assoumane, A.; Serret, J.; Noe, S.; Favreau, B.; Vaillant, A.; Gâteblé; G; Pain, A. ; Papineau, C.; Maggia, L. Structure and genetic diversity of Ixora margaretae, an endangered species: A baseline study for conservation and restoration of natural dry forest of New Caledonia. Tree Genetics & Genomes 2013, 9, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segar, S.T.; Volf, M.; Zima Jnr, J.; Isua, B.; Sisol, M.; Sam, L.; Sam, K.; Souto-Vilarós, D.; Novotny, V. Speciation in a keystone plant genus is driven by elevation: A case study in New Guinean Ficus. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2017, 30, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lan, J.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Lu, W.; Lin, Y.; Luo, J. Population structure and genetic diversity in Eucalyptus pellita based on SNP markers. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1278427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, J.J.; Wieczorek, A.M.; Meyer, J.Y. Genetic diversity and structure of the invasive tree Miconia calvescens in Pacific islands. Diversity and Distributions 2008, 14, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.A. Phylogenetic and functional trait-based community assembly within Pacific Cyrtandra (Gesneriaceae): Evidence for clustering at multiple spatial scales. Ecology and Evolution 2023, 13, e10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomizawa, Y.; Tsuda, Y.; Nazre, M.; Wee, A.K. S. , Takayama, K., Yamamoto, T., Yllano, O., Salmo, S., Sungkaew, S., Adjie, B., Ardli, E., Suleiman, M., Tung, N., Soe, K., Kandasamy, K., Asakawa, T., Watano, Y., Baba, S., & Kajita, T. Genetic structure and population demographic history of a widespread mangrove plant Xylocarpus granatum J. Koenig across the Indo-West Pacific Region. Forests 2017, 8, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPC 2012. Regional workshop on Forest Genetic Resources in the Pacific. Suva, Fiji Islands: Secretariat of the Pacific Community. https://spccfpstore1.blob.core.windows.net/digitallibrary-docs/files/ee/ee591e21351d5436d0cb12fe3218b0f2.pdf.

- Gamoga, G.; Turia, R.; Abe, H.; Haraguchi, M.; Iuda, O. The forest extent in 2015 and the drivers of forest change between 2000 and 2015 in Papua New Guinea. Case Studies in the Environment 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Ashman, K.; Lindenmayer, D.; Legge, S.; Kindler, G.; Cadman, T.; Fletcher, R.; Whiterod, N.; Lintermans, M.; Zylstra, P.; Stewart, R.; Thomas, H.; Blanch, S.; Watson, J.E.M. (2023). The impacts of contemporary logging after 250 years of deforestation and degradation on forest-dependent threatened species. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F. Reflections on the tropical deforestation crisis. Biological Conservation 1999, 91, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, J.M. A socio-economic analysis of mangrove degradation in Samoa. Geographical Review of Japan Series B 2001, 74, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G. Mining and the environment in Melanesia: Contemporary debates reviewed. The Contemporary Pacific 2002, 14, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feary, A. (2011). Restoring the soils of Nauru: Plants as tools for ecological recovery [Master’s thesis, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington].

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari JR, Arico S,Báldi, A. The IPBES conceptual framework—Connecting nature and people. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenga, T.F. L. , Zulu, J.M., Corbin, J.H., & Mweemba, O. Dismantling historical power inequality through authentic health research collaboration: Southern partners’ aspirations. Global Public Health 2021, 16, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabobo-Baba, U. Decolonising framings in Pacific research: Indigenous Fijian vanua research framework as an organic response. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2008, 4, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Morrison, C.; Watling, D.; Tuiwawa MV,Rounds, I. A. Conservation in tropical Pacific Island countries: Why most current approaches are failing. Conservation Letters 2012, 5, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson-Fua, S. (2023). Kakala research framework. In Varieties of qualitative research methods: Selected contextual perspectives (pp. 275–280). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, B.J.; Kjær, E.D. (2007). Forest genetic diversity and climate change: Economic considerations. In Climate change and forest genetic diversity: Implications for sustainable forest management in Europe (pp. 69–84). Bioversity International, Rome, Italy.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).