Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

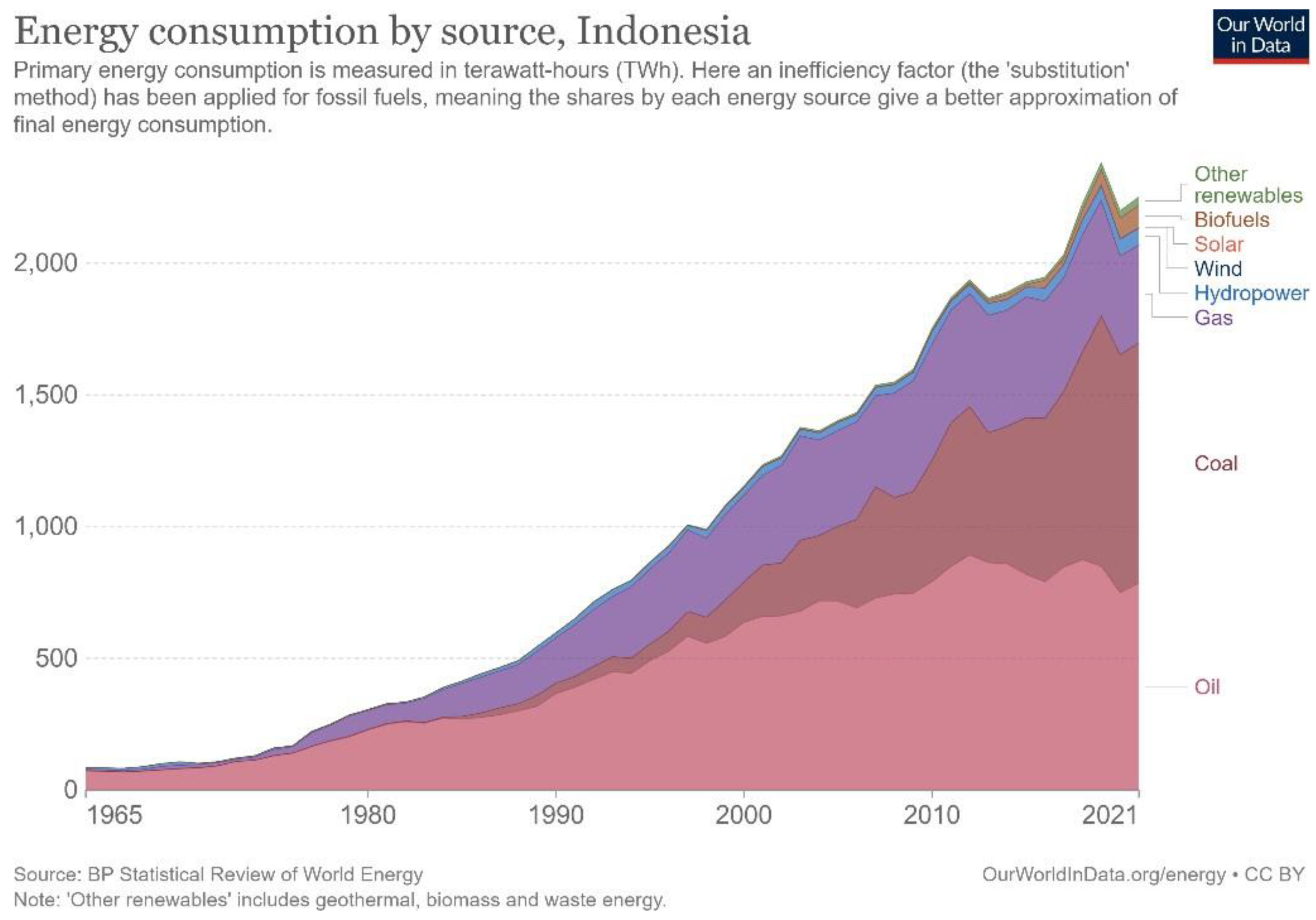

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Research Objective and Contribution

1.4. Research Question

- What is the current situation of solar PV systems under the RPVSS policy in Indonesia to address energy trilemma?

- What are the public perceptions toward usefulness, ease of use, affordability, and environmental awareness regarding solar PV systems addressed by RPVSS policy in Indonesia?

- What recommendations can be formulated to improve the technological acceptance of the public?

2. Literature Review

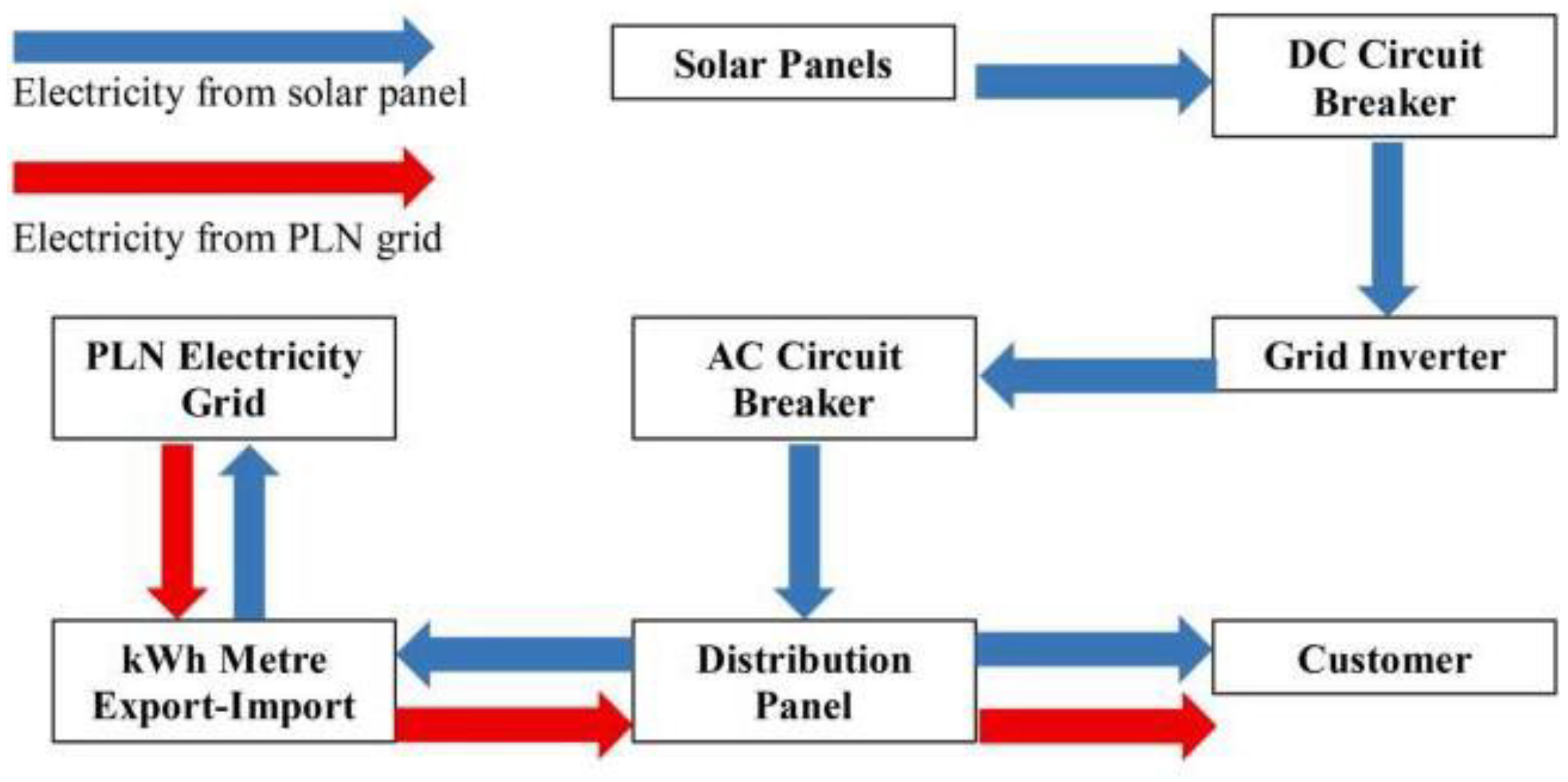

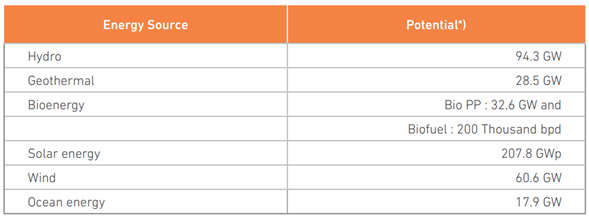

2.1. Solar PV Systems Development in Indonesia

2.2. Rooftop Photovoltaic Solar Systems Policy in Indonesia

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Energy Transition in the Context of Energy Trilemma

3.1.1. Energy Affordability

3.1.2. Energy Security

3.1.3. Environmental Sustainability

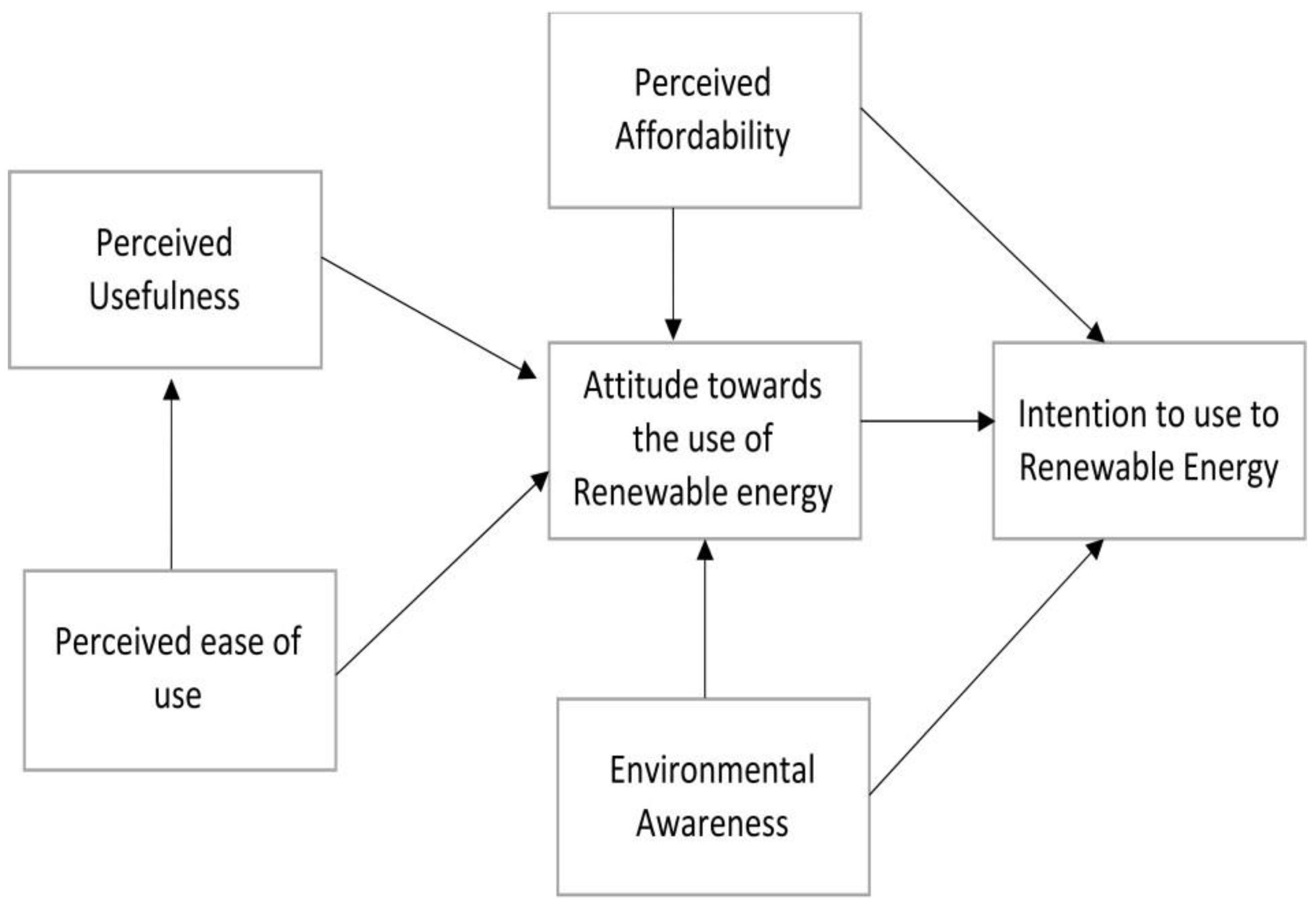

3.2. Technological Acceptance Model

3.2.1. Perceived Usefulness

3.2.2. Perceived Ease of Use

3.2.3. Perceived Affordability

3.2.4. Environmental Awareness

3.2.5. TAM Indicator

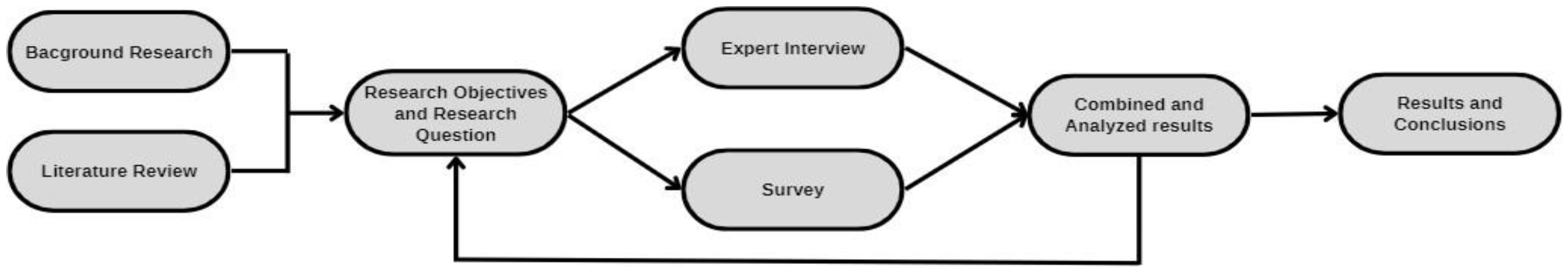

4. Methodology

4.1. Content Analysis

4.2. Survey Design

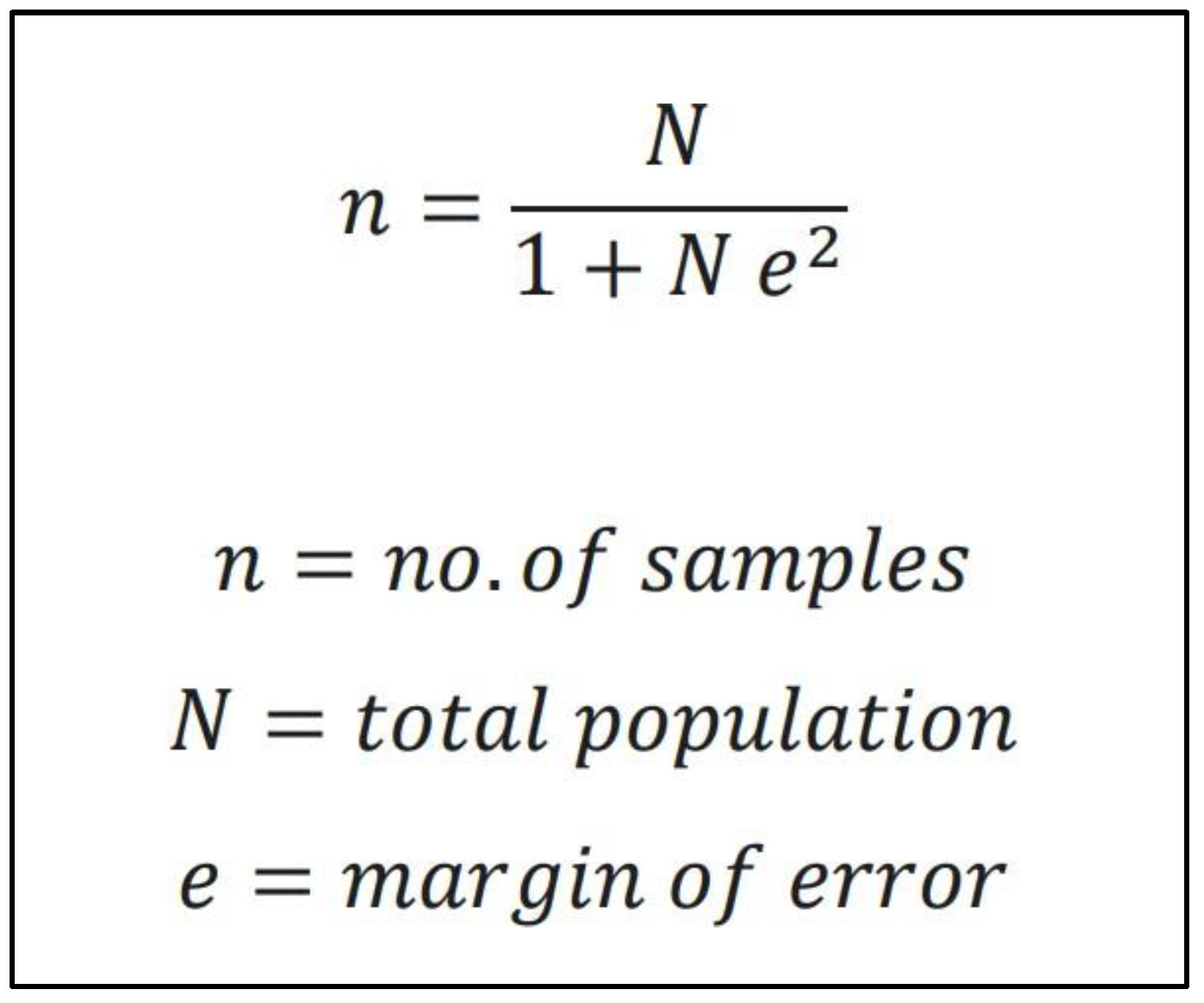

5. Conclusions

References

- Ajzen, I., Gilbert Cote, N.G. (2008). Attitudes and the Prediction of Behavior. In Attitudes and Attitude Change; Crano, W.D., Prislin, R., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, pp. 289– 311.

- Bergek, A., Hekkert, M. P., & Jacobsson, S. (2008). Functions in innovation systems: A framework for analysing energy system dynamics and identifying goals for system-building activities by entrepreneurs and policy makers. Foxon, T., Köhler, J. and Oughton, C. (Eds): Innovations for a Low Carbon Economy: Economic, Institutional and Management Approaches, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2008, 79–111.

- Dang, Minh-Quan. (2017). Solar Energy Potential in Indonesia. Conference Paper. Link. htt ps://www.researchgate.net/publication/324840601_SOLAR_ENERGY_POTENTIAL_ IN_INDONESIA. Accessed 3 June 2019.

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. (1989). User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci, 35, 982–1003.

- Dubey, S., Jadhav, N. L., & Zakirova, B. (2013). Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of Silicon Based Photovoltaic (PV) Technologies. Energy Procedia, 33, 322–334. [CrossRef]

- Ducey, A.J. Coovert, M.D. (2016). Predicting Tablet Computer Use: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model for Physicians. Health Policy Technol. 5, 268–284.

- Gnansounou, E. (2008). Assessing the energy vulnerability: Case of industrialised countries. Energy Policy, 36(10), 3734–3744. [CrossRef]

- Grubler, A. (2012). Energy transitions research: Insights and cautionary tales. Energy Policy, 50, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. (2012). Getting the Measure of Fuel Poverty. Final Report of the Fuel Poverty Review. CASE Report 72. The London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

- IEA. (2021). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Data Explorer https://www.iea.org/data- and-statistics/data-tools/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy-data-explorer.

- IEEFA. (n.d.). IEEFA report: Indonesia's solar policies – designed to fail? https://ieefa.org/articles/ieefa-report-indonesias-solar-policies-designed-fail.

- IESR. (2019). Indonesia Clean Energy Outlook: Tracking Progress and Review of Clean Energy Development in Indonesia. Jakarta.

- Keppler, J.H. (2007). International Relations and Security of Energy Supply: Risks to Continuity and Geopolitical Risks. University of Paris-Dauphine /http://www. ifri.org/frontDispatcher/ifri/publications/ouvrages_1031930151985/ publi_P_energie_jhk_securityofsupplyeuparlt_1174559165992S.

- Kristiawan, R., Widiastuti, I., & Suharno, S. (2018). Technical and economical feasibility analysis of photovoltaic power installation on a university campus in indonesia. MATEC Web of Conferences, 197, 08012. [CrossRef]

- Lieb-Doczy, E., Börner, A., & MacKerron, G. (2003). Who Secures the Security of Supply? European Perspectives on Security, Competition, and Liability. The Electricity Journal, 16(10), 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Maulidia, M., Dargusch, P., Ashworth, P., Ardiansyah, F. (2019). Rethinking renewable energy targets and electricity sector reform in Indonesia: a private sector perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 101, 231–247.

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources Republic of Indonesia. (2019). National Energy General Plan (Rencana Umum Energi Nasional: RUEN).

- Mujiyanto, S., Tiess, G. (2013). Secure energy supply in 2025: Indonesia’s need for an energy policy strategy. Energy Pol. 61, 31–41.

- OEC. (2021). OEC - the Observatory of Economic Complexity. Crude Petroleum in Indonesia https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/crude-petroleum/reporter/idn.

- Ölz, S., Sims, R., Kirchner, N. (2007). Contribution of Renewables to Energy Security. IEA /http://www.iea.org/textbase/papers/2007/so_contribution.pdfS.

- Pastukhova, M., & Westphal, K. (2020). Governing the Global Energy Transformation. In Lecture notes in energy (pp. 341–364). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F. A. (2022). Techno-economic analysis of rooftop solar power plant implementation and policy on mosques: An Indonesian case study. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Qolbi, A. P. N. (2020). The Emergence of Solar Photovoltaic Technology in Indonesia: Winners and Losers. E3S Web of Conferences. [CrossRef]

- Resosudarmo, B., Alisjahbana, A. and Nurdianto, D. (2010) Energy Security in Indonesia, ANU Working paper in Trade and Development, Crawford School, ANU: Canberra.

- Ritchie, H. (2022b, October 27). Energy. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/indonesia.

- Rutherford, J., Scharpf, E., & Carrington, C. G. (2007). Linking consumer energy efficiency with security of supply. Energy Policy, 35(5), 3025–3035. [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, D. (2020). Analysis of perceptions towards the rooftop photovoltaic solar system policy in Indonesia. Energy Policy, 144, 111569. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Strategic placement of charging stations for enhanced electric vehicle adoption in San Diego, California. Journal of Transportation Technologies, 14(1), 64–81. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., Patel, D., & Swami, G. (2024). Reducing electrical consumption in stationary long-haul trucks. Open Journal of Energy Efficiency, 13(3), 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., Patel, D., & Swami, G. (2024). Strategic insights into vehicles fuel consumption patterns: Innovative approaches for predictive modeling and efficiency forecasting. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 13(6), 1–10.

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Comprehensive examination of solar panel design: A focus on thermal dynamics. Sustainable Green Energy Research & Engineering, 15(1), 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). Comprehensive examination of solar panel design: A focus on thermal dynamics. Sustainable Green Energy Research & Engineering, 15(1), Article 151002. [CrossRef]

- Swami, G., Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2025). From ground to grid: The environmental footprint of minerals in renewable energy supply chains. Current World Environment and Energy Economics, 14(1), Article 141002. [CrossRef]

- Swami, G., Sheth, K., & Patel, D. (2024). PV capacity evaluation using ASTM E2848: Techniques for accuracy and reliability in bifacial systems. Sustainable Green Energy Research & Engineering, 15(9), Article 159012. [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, D. F., Blakers, A., Stocks, M., Lu, B., Cheng, C., & Hayes, L. (2021). Solar PV Resource Assesment for Indonesia’s Energy Future. Photovoltaic Specialists Conference. [CrossRef]

| Category | Indicator |

|---|---|

|

Perceived Usefulness |

Provide daily needs of electricity |

| Lower electricity bill | |

| Enable tasks without extensive efforts | |

|

Environmental Awareness |

Manufacture impact |

| Reduce GHG emissions | |

| The existence of solar panel waste treatment | |

| Reduce dependence on fossil fuels | |

|

Perceived Affordability |

The upfront cost to adopt solar PV |

| Maintenance cost | |

| Return on Investment | |

|

Perceived Ease of Use |

The initial process to adopt solar PV |

| House compatibility | |

| Frequency of maintenance | |

| Frequency of interaction | |

| Technical obstacle |

| Numerical Value | Perception Value |

|---|---|

| 1 | Strongly Disagree |

| 2 | Disagree |

| 3 | Neutral |

| 4 | Agree |

| 5 | Strongly Agree |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).