Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures and Measurements

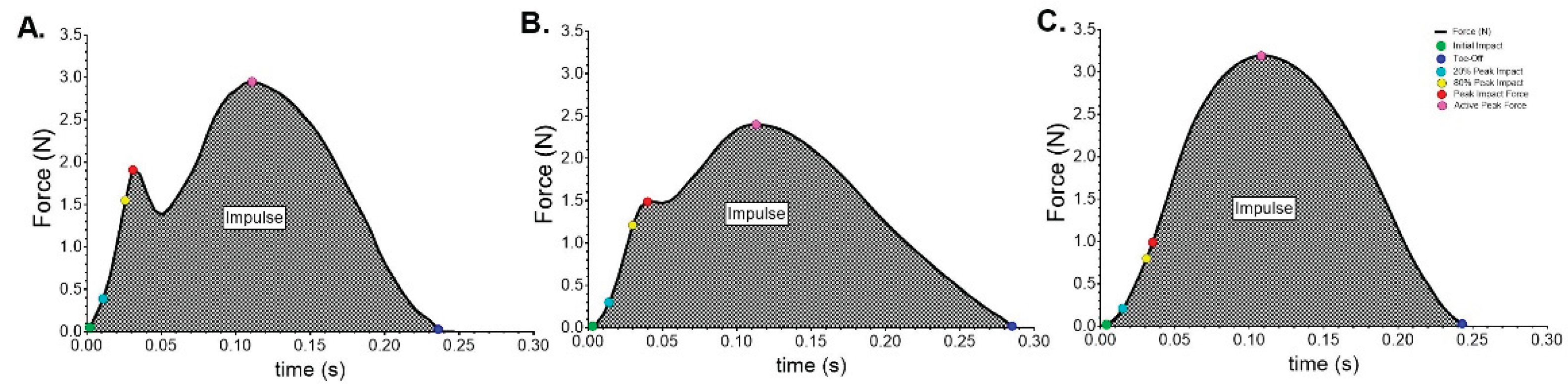

- Stride duration was the time from one initial impact to the next initial impact for the same foot.

- Ground contact time (s) was the time the foot remained in contact with the treadmill surface i.e. toe-off – initial contact times.

- Swing time (s) was the time the foot has no contact with the treadmill surface.

- Active peak vertical force (N∙BW-1) was the second peak for heel strike runners, or the highest force reading of each step for midfoot and forefoot strikers.

- Peak vertical impact force (N∙BW-1) identified as the first peak in the total force trace between initial contact and the active peak. If the first peak was not present in running (mid-forefoot strike) it was defined as the force at 13% of the ground contact time.

- Average loading rate (N∙BW-1∙s-1) is the difference between forces at 20% and 80% of the peak impact force divided by the corresponding time interval (s).

- Impulse (N∙s∙BW-1), the area under the force-time curve.

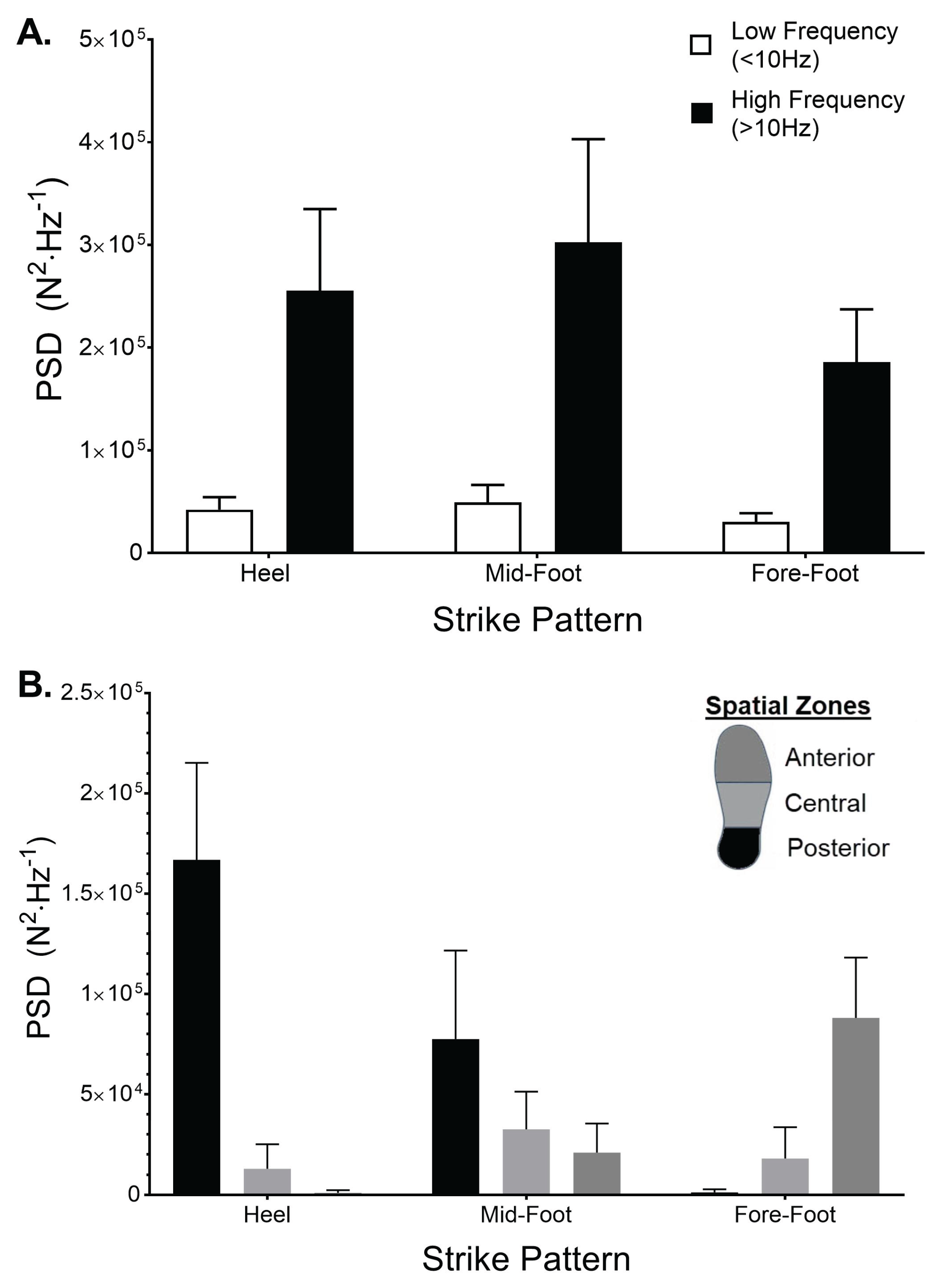

- Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis: During the stance phase, while the right foot was in contact with the ground, force data (total and spatial zones) were analysed in the frequency domain. PSD was computed using Welch’s [33] method (MATLAB, default windowing), and applied to the first 20% of each step’s stance phase to isolate impact related portion of ground contact. A frequency resolution of 2 Hz was used from 0-100 Hz. PSD values were retained in their raw form (N2∙Hz-1), preserving magnitude to reflect actual spectral energy differences across the zones in relation to strike pattern. Spectral power was partitioned into low-frequency (<10 Hz) and high-frequency (10-100 Hz) bands to quantify relative contributions and frequency dependent loading characteristics.

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lieberman, D.E.; Venkadesan, M.; Werbel, W.A.; Daoud, A.I.; D’Andrea, S.; Davis, I.S.; Mang’Eni, R.O.; Pitsiladis, Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature 2010, 463, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasmer, M.E.; Liu, X.-c.; Roberts, K.G.; Valadao, J.M. Foot-Strike Pattern and Performance in a Marathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2013, 8, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsted, C.; Larsen, L.H.; Nielsen, R.O. Reliability of video-based identification of footstrike pattern and video time frame at initial contact in recreational runners. Gait & Posture 2015, 42, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, K.; Hagio, S.; Kibushi, B.; Moritani, T.; Kouzaki, M. Comparison of muscle synergies for running between different foot strike patterns. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, P.R.; Lafortune, M.A. Ground reaction forces in distance running. J. Biomech. 1980, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giandolini, M.; Poupard, T.; Gimenez, P.; Horvais, N.; Millet, G.Y.; Morin, J.-B.; Samozino, P. A simple field method to identify foot strike pattern during running. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; Gonzalez, O. Leg stiffness and stride frequency in human running. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Z.Y.S.; Au, I.P.H.; Lau, F.O.Y.; Ching, E.C.K.; Zhang, J.H.; Cheung, R.T.H. Does maximalist footwear lower impact loading during level ground and downhill running? Eur J Sport Sci 2018, 18, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, B.M.; Liu, W. The effect of muscle stiffness and damping on simulated impact force peaks during running. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, B.M.; Bahlsen, H.A.; Luethi, S.M.; Stokes, S. The influence of running velocity and midsole hardness on external impact forces in heel-toe running. J. Biomech. 1987, 20, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Calculation and interpretation of mechanical energy of movement. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 1978, 6, 183–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Jim, R.; Taylor, P.J.; Edmundson, C.J.; Brooks, D.; Hobbs, S.J. Three-dimensional kinematic comparison of treadmill and overground running. Sports Biomech. 2013, 12, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, R.; Griffin, T.M.; Donelan, J.M.; Chang, Y.H. Force treadmill for measuring vertical and horizontal ground reaction forces. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hooren, B.; Fuller, J.T.; Buckley, J.D.; Miller, J.R.; Sewell, K.; Rao, G.; Barton, C.; Bishop, C.; Willy, R.W. Is Motorized Treadmill Running Biomechanically Comparable to Overground Running? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Over Studies. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 785–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmussen, M.J.; Kaltenbach, C.; Hashlamoun, K.; Shen, H.; Federico, S.; Nigg, B.M. Force measurements during running on different instrumented treadmills. J. Biomech. 2019, 84, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pérez, J.A.; Pérez-Soriano, P.; Llana, S.; Martínez-Nova, A.; Sánchez-Zuriaga, D. Effect of overground vs treadmill running on plantar pressure: Influence of fatigue. Gait & Posture 2013, 38, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluitenberg, B.; Bredeweg, S.W.; Zijlstra, S.; Zijlstra, W.; Buist, I. Comparison of vertical ground reaction forces during overground and treadmill running. A validation study. BMC Musculoskel. Disord. 2012, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.E.F.; Fonseca, J.B.; Oliveira, A.I.S.d.; Cabral, K.D.d.A.; Araújo, M.d.G.R.d.; Ferreira, A.P.d.L. Prevalence and factors associated with injuries in recreational runners: A cross-sectional study. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.D.; Tenforde, A.S.; Outerleys, J.; Reilly, J.; Davis, I.S. Impact-Related Ground Reaction Forces Are More Strongly Associated With Some Running Injuries Than Others. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 48, 3072–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.I.; Bradley, J.B.; David, R.M. Greater vertical impact loading in female runners with medically diagnosed injuries: A prospective investigation. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.E.; Frederick, E.C.; Cooper, L.B. Effects of Shoe Cushioning Upon Ground Reaction Forces in Running. Int. J. Sports Med. 1983, 04, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, S.A.; Kluitenberg, B.; Dekker, R.; Bredeweg, S.W.; Postema, K.; Van den Heuvel, E.R.; Hijmans, J.M.; Sobhani, S. Running with a minimalist shoe increases plantar pressure in the forefoot region of healthy female runners. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmala, J.-P.; Kosonen, J.; Nurminen, J.; Avela, J. Running in highly cushioned shoes increases leg stiffness and amplifies impact loading. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 17496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, J.J.; Pollard, C.D. Differences in running biomechanics between a maximal, traditional, and minimal running shoe. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.O.; Davis, I.S.; Lopes, A.D. Biomechanical Differences of Foot-Strike Patterns During Running: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2015, 45, 738–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorten, M.; Mientjes, M.I.V. The ‘heel impact’ force peak during running is neither ‘heel’ nor ‘impact’ and does not quantify shoe cushioning effects. Footwear Science 2011, 3, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.H.; Boyer, K.A.; Derrick, T.R.; Hamill, J. Impact shock frequency components and attenuation in rearfoot and forefoot running. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2014, 3, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.H.; Edwards, W.B.; Hamill, J.; Derrick, T.R.; Boyer, K.A. A comparison of the ground reaction force frequency content during rearfoot and non-rearfoot running patterns. Gait & Posture 2017, 56, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.S.; McClay, I.S.; Manal, K.T. Lower Extremity Mechanics in Runners with a Converted Forefoot Strike Pattern. J Appl Biomech 2000, 16, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.; Lin, K.-L.; Shiang, T.-Y. Is the foot striking pattern more important than barefoot or shod conditions in running? Gait & Posture 2013, 38, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdermid, P.W.; Walker, S.J.; Cochrane, D. The Effects of Cushioning Properties on Parameters of Gait in Habituated Females While Walking and Running. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, K.E.; Peebles, A.T.; Socha, J.J.; Queen, R.M. The impact of sampling frequency on ground reaction force variables. J. Biomech. 2022, 135, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zeng, Z.; Mo, S.; Wang, L. Influences of footstrike patterns and overground conditions on lower extremity kinematics and kinetics during running: Statistical parametric mapping analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulmala, J.-P.; Avela, J.; Pasanen, K.; Parkkari, J. Forefoot strikers exhibit lower running-induced knee loading than rearfoot strikers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, B.M.; Vienneau, J.; Smith, A.C.; Trudeau, M.B.; Mohr, M.; Nigg, S.R. The Preferred Movement Path Paradigm: Influence of Running Shoes on Joint Movement. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Michele, R.; Merni, F. The concurrent effects of strike pattern and ground-contact time on running economy. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, S.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; Dekker, R.; Postema, K.; Kluitenberg, B.; Bredeweg, S.W.; Hijmans, J.M. Biomechanics of running with rocker shoes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, C.E.; Ferber, R.; Pollard, C.D.; Hamill, J.; Davis, I.S. Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Carranza, V.; Hoogkamer, W.; González-Ravé, J.M.; Horta-Muñoz, S.; Serna-Moreno, M.d.C.; Romero-Gutierrez, A.; González-Mohíno, F. Influence of different midsole foam in advanced footwear technology use on running economy and biomechanics in trained runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2024, 34, e14526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.; Malisoux, L.; Urhausen, A.; Statham, A.; Meijer, K.; Theisen, D. The effect of shoe type and fatigue on strike index and spatiotemporal parameters of running. Gait & Posture 2015, 42, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.A.; Horsch, S. Heel–toe running: A new look at the influence of foot strike pattern on impact force. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness 2015, 13, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napier, C.; Fridman, L.; Blazey, P.; Tran, N.; Michie, T.V.; Schneeberg, A. Differences in Peak Impact Accelerations Among Foot Strike Patterns in Recreational Runners. Front Sports Act Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strike Pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heel | Mid-Foot | Fore-Foot | |

| Stride duration (s) | 0.762 ± 0.035 | 0.753 ± 0.043 | 0.760 ± 0.039 |

| Ground contact time (s) | 0.257 ± 0.018 | 0.253 ± 0.012 | 0.253 ± 0.015 |

| Swing time (s) | 0.505 ± 0.049 | 0.500 ± 0.052 | 0.508 ± 0.050 |

| Peak Impact Force (N∙BW-1) | 1.64 ± 0.35 | 1.74 ± 0.31 | 1.37 ± 0.34 |

| Average Loading Rate (N∙s-1∙BW-1) | 53.7 ± 16.1 | 55.3 ± 13.2 | 39.11 ± 12.6 |

| Active Peak Force (N∙BW-1) | 2.93 ± 0.35 | 3.04 ± 0.30 | 3.31 ± 0.26 |

| Impulse (N∙s∙BW-1) | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| Strike Pattern | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heel | Mid-Foot | Fore-Foot | |||||||

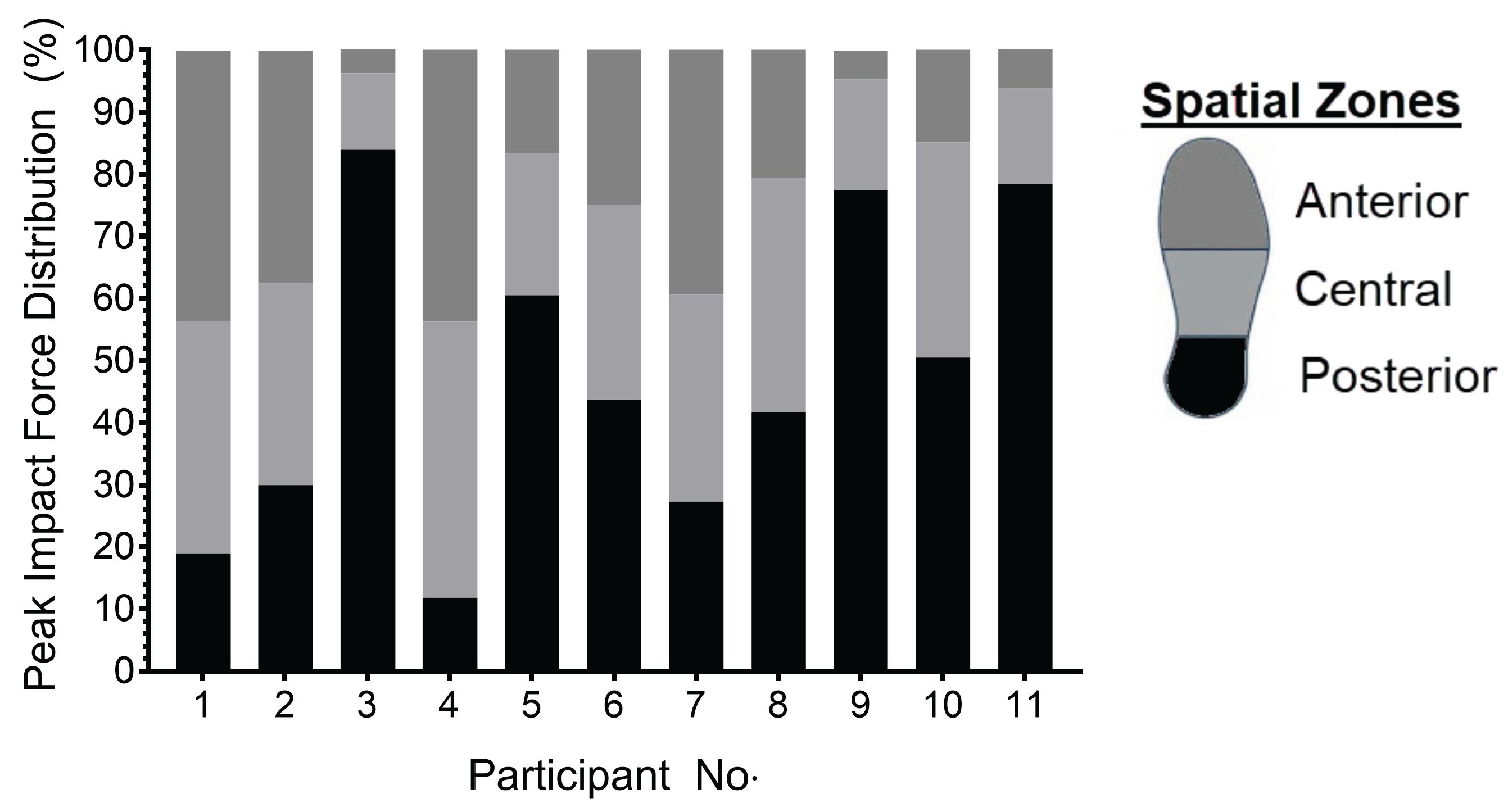

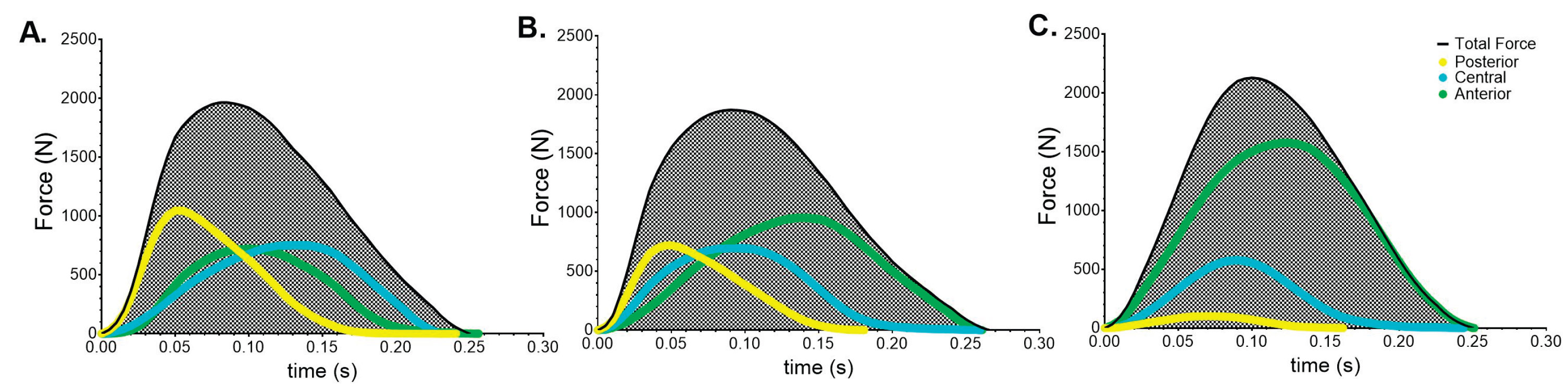

| Spatial Zone | Posterior | Central | Anterior | Posterior | Central | Anterior | Posterior | Central | Anterior |

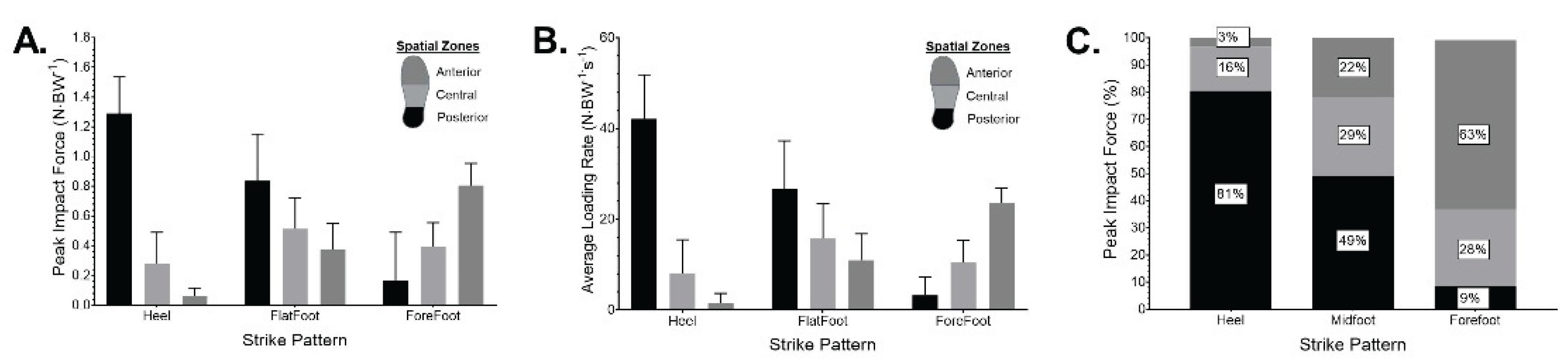

| Peak Impact Force (N∙BW-1) | 1.29±0.25 | 0.28±0.21 | 0.17±0.33 | 0.84±0.31 | 0.52±0.21 | 0.17±0.33 | 0.17±0.33 | 0.39±0.17 | 0.81±0.15 |

| Average Loading Rate (N∙s-1∙BW-1) | 42.16±9.70 | 8.17±7.32 | 1.15±2.15 | 26.68±10.63 | 15.76±7.71 | 11.01±5.81 | 3.28±4.05 | 10.46±4.92 | 23.58±3.31 |

| Active Peak Force (N∙BW-1) | 1.06±0.03 | 0.98±0.23 | 0.89±0.11 | 0.64±0.28 | 0.97±0.24 | 1.43±0.26 | 0.18±0.22 | 0.82±0.34 | 2.12±0.53 |

| Impulse (N∙s∙BW-1) | 0.16±0.03 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.17±0.02 | 0.09±0.04 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.25±0.04 | 0.02±0.03 | 0.10±0.04 | 0.37±0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).