1. Introduction

Hybridization and introgression occur frequently in nature and can be an important source of genetic variation in species (Arnold, 1997; Dowling & Secor, 1997; Edelman & Mallet, 2025; Hedrick, 2013; Mallet, 2005). Discordant patterns of mitonuclear introgression, which in the most extreme cases can result in mitogenome replacement even in the absence of measurable nuclear introgression, are well documented (Toews & Brelsford, 2012). Furthermore, the evidence of historical hybrid zones that have moved or disappeared is often apparent from genetic traces of introgression in the extant populations of impacted species (Wielstra, 2019).

Introgression may be driven by deterministic factors. Natural selection may favor introgression of locally adapted mitogenomes when species encounter novel or extreme environments or drive genetic rescue when mitogenomes have accumulated mutation load (Bonnet et al., 2017; Hill, 2019; Sloan et al., 2017). Mitochondrial replacement also may be nonadaptive and driven by sex-biased fitness of hybrid offspring (Dowling & Hoeh, 1991; Gerber et al., 2001; MacPherson et al., 2023). Alternatively, introgression may be driven as an outcome of range shifts and species invasion. When range shifts lead to invading species encountering congeneric species and engaging in hybridization, the outcome can lead to massive introgression in the genome of the invading species as a purely neutral demographic process (Currat et al., 2008; Wielstra & Arntzen, 2012).

Hybridization is common in fishes (Hubbs, 1955), and particularly prevalent in minnows and shiners of the family Leuciscidae (Scribner et al., 2001; Zbinden et al., 2023). Multi-species unguarded nesting behaviors are common among minnows and shiners and associated with high rates of hybridization (Corush et al., 2021). Discordant mitonuclear introgression patterns have been extensively reported among fish species, with examples of complete mitogenome replacement at the population level reported in charrs (Doiron et al., 2002; Wilson & Bernatchez, 1998), cichlids (Nevado et al., 2009), darters (Bossu & Near, 2009), pupfish (Carson & Dowling, 2006), topminnows (Duvernell & Schaefer, 2014), and shiners in the genus Luxilus (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995).

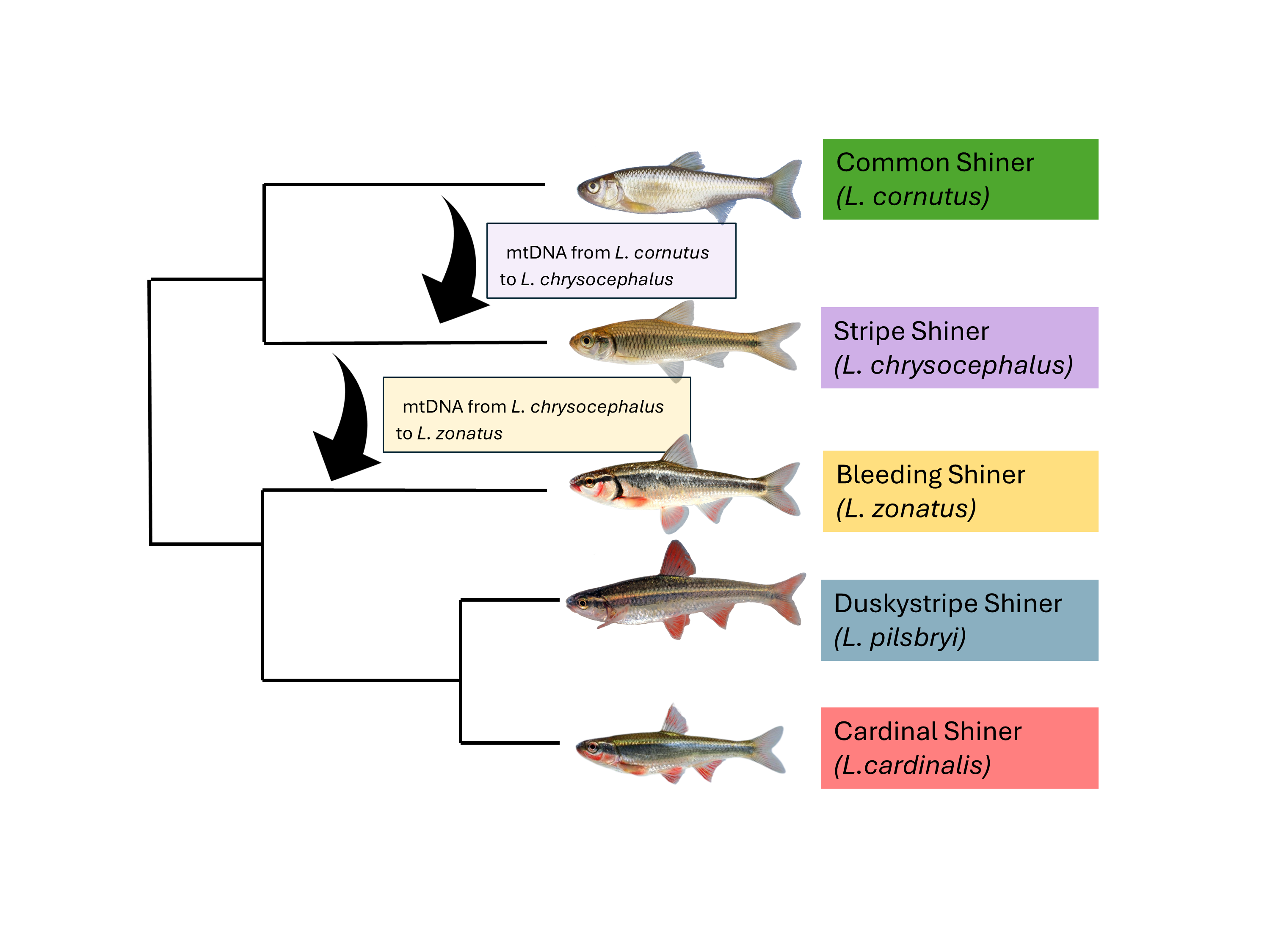

The genus Luxilus is comprised of nine North American shiner species (Dowling & Naylor, 1997). Studies have demonstrated the frequent occurrence of hybridization among sympatric Luxilus species (Dowling et al., 1989; Dowling & Moore, 1984; Meagher & Dowling, 1991), and members of the genus commonly spawn in heterospecific groups that can include multiple congeners (Pflieger, 1997). Within the zone of extant sympatry between L. chrysocephalus and L. cornutus, mechanisms of reproductive isolation and the dynamics of hybridization vary among populations isolated in separate drainages (Dowling et al., 1997; Dowling & Hoeh, 1991; Gleason & Berra, 1993). In the Ozark Interior Highlands, outside the zone of extant species sympatry, historical hybrid introgression has resulted in L. chrysocephalus populations in drainages throughout the region appearing monomorphic for L. cornutus mitogenomes (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995).

Recently, it was discovered that L. zonatus populations in some Ozark drainages exhibit L. chrysocephalus mitogenomes (Halas, 2011). What makes this particularly noteworthy is that in the river drainages where L. zonatus exhibit L. chrysocephalus mitogenomes, the L. chrysocephalus populations themselves are monomorphic for L. cornutus mitogenomes, suggesting a complex history of hybridization, introgression, and serial mitogenome replacement among Luxilus species in the Ozarks (Halas, 2011). The objective of our study was to determine the geographic extent of mitogenome introgression among L. zonatus populations, determine which drainages were impacted, and interpret these introgression events in a historical phylogeographic context.

2. Materials and Methods

The genus Luxilus is a relatively common minnow found throughout the eastern United States, including the cornutus and zonatus species groups. The cornutus group is comprised of four species, L. chrysocephalus, L. cornutus, L. cerasinus, and L. albeolus. Luxilus chrysocephalus is one of the most widely distributed members of this group with a range that spans the southern Great Lakes and the eastern two-thirds of the Mississippi River basin, as well as south into Gulf Coast drainages. Luxilus cornutus, has a similarly large range but is more northern in its distribution, including the northwestern portion of the Mississippi River basin, through the Great Lakes basin, and extending east to Atlantic drainages from Nova Scotia to the mid-Atlantic coast. A zone of extant sympatry between the species spans drainages of the Great Lakes, upper Illinois River, and portions of the upper Ohio River basin. The other two species of the group are more narrowly distributed in mid-Atlantic drainages with L. albeolus ranging from the Roanoke River of Virginia, southward to the Cape Fear River of North Carolina while L. cerasinus is found primarily in the Roanoke and New rivers.

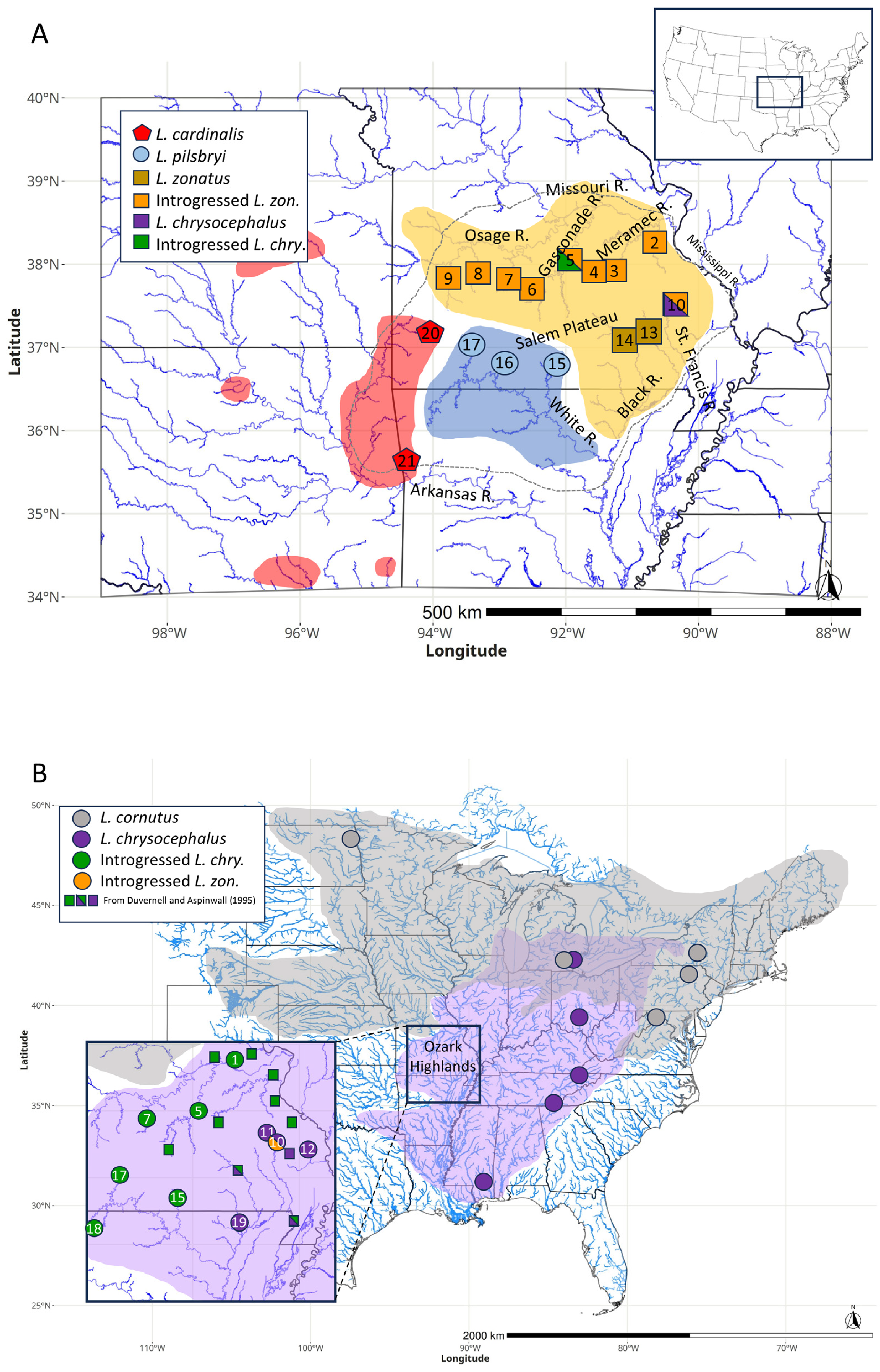

There are three allopatric species in the L. zonatus species group, restricted mostly to the Ozark Highlands. They include L. cardinalis in the Arkansas River drainage, L. pilsbryi in the White River drainage, and L. zonatus in Missouri and Mississippi River tributaries that drain the Ozarks, including the Osage, Gasconade, and Meramec River drainages in the northern Ozark Highlands, and the Black and St. Francis River drainages in the southeastern Ozark Highlands (Mayden, 1988). All three species in the L. zonatus complex are sympatric with L. chrysocephalus.

We sampled

L. zonatus from eleven sites in each of five major Ozark river drainages where they are found, along with

L. pilsbryi from three sites in the White River drainage, and

L. cardinalis from two sites in the Arkansas River drainage (

Table 1). Specimens were collected by seining moderate to strong flowing current in the main channels of creeks and rivers. We also collected

L. chrysocephalus from ten sites within the Ozark Highland study area (

Table 1) and combined current with previously reported results (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995) for the species in this region. Additional reference sequences of

Luxilus species outside the Ozark Highlands study area were included from previous published and unpublished sources (Dowling et al., 1992; Dowling & Naylor, 1997).

Fin clips were preserved in 95% ethanol, and voucher specimens were preserved in 10% formalin. All specimens were identified to species based on diagnostic morphological features (Pflieger, 1997). Ozark Highlands samples collected for this study were extracted using Blood and Tissue extraction columns (Qiagen). Subunit 2 of the NADH dehydrogenase gene (ND2) of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was isolated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers designed from an L. chrysocephalus reference sequence. The primers were LuxND2_4010F 5’-GCCCATACCCCGAACATGAC-3’ and LuxND2_5145R 5’-TCTGCTTAGAGCTTTGAAGGCT-3’. PCR was conducted using Thermo Scientific PCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Fischer), and cycling conditions of an initial denaturing step at 95oC for 4 min, 35 cycles of 95oC for 30 sec, 58oC for 30 sec, and 72oC for 45 sec, followed by 72oC for 4 min. PCR products were prepared for Sanger Sequencing using HighPrep PCR magnetic beads (Magbio Genomics). Sanger Sequencing of forward and reverse strands was conducted at the MU Genomic Technology Core (mugenomicscore.missouri.edu/) using the PCR primers. Chromatograms were assembled and aligned using Geneious Prime (Dotmatics). Additional reference samples of Luxilus species were prepared using similar PCR and Sanger sequencing methods as previously described (Dowling & Naylor, 1997).

A phylogeny was generated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method employed in MEGA11 (Tamura et al., 2021) with the GTR+I nucleotide substitution model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Ericymba dorsalis, Notropis atherinoides, and N. buccata were included as outgroups. Nucleotide diversity (π), and nucleotide divergence (Dxy) parameters were estimated from ND2 sequence alignments using DnaSP 6.12.03 (Rozas et al., 2017).

Molecular divergence times of mitochondrial lineages were estimated using the suite of programs from BEAST 2.7.3 (Bouckaert et al., 2019) and reported as mean divergence time +/- 95% HPDs. Fossil-based calibration is confounded in Leuciscids by a poor fossil record. Therefore, we conservatively employed a uniform prior distribution of divergence rates as recommended by Smith and Larson (pers. comm.) to generate estimates of divergence time. Divergence rates for minnows and suckers correlate with size. Luxilus minnows (3g – 100g) lie at the low end of the size range for the family, with a corresponding expected rate of 2.5 – 3.5 times the pairwise divergence rate per million years. Input files were generated using BEAUti 2 and *BEAST was run with a species tree relaxed clock with a log normal rate distribution spanning the rate range reported by Smith and Larson. Analyses were run for 20 million generations with parameters logged every 1,000 generations. Multiple runs were conducted, and outputs were examined in Tracer 1.7.2 (Drummond & Rambaut, 2007) to verify that key parameters had effective sample sizes of 200 or greater. Log and tree files from four runs were combined using LogCombiner 2.7.3 (Drummond & Rambaut, 2007). with a 10% burnin. Mean age estimates and topology were based on the maximum clade credibility using common ancestor heights from our combined trees using TreeAnnotator 2.7.3 and the tree was visualized in FigTree 1.4.4.

3. Results

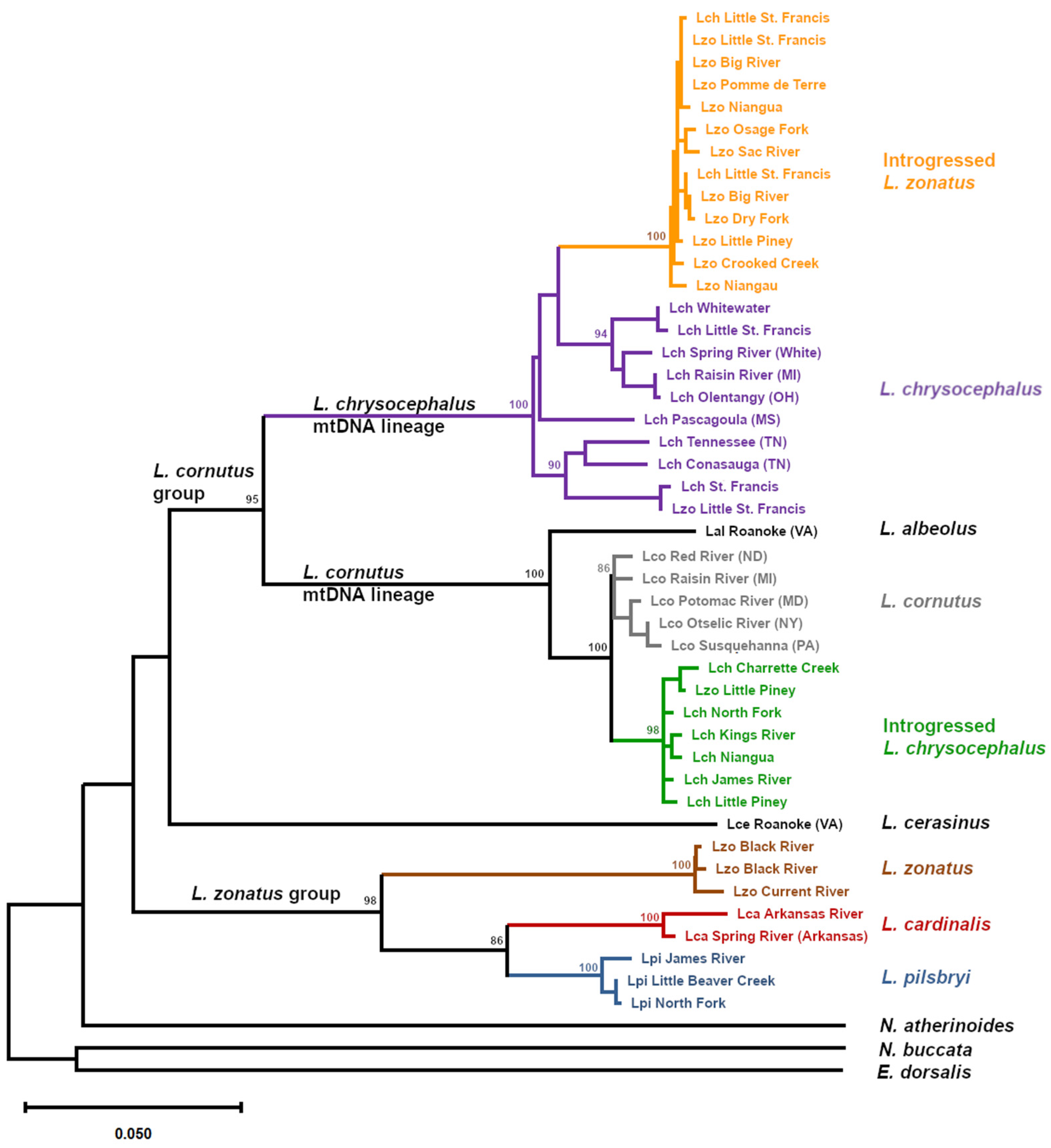

A mtDNA ML phylogeny (

Figure 1) was consistent with previously reported species relationships in the genus

Luxilus (Dowling & Naylor, 1997). Samples of the

L.

zonatus group (

L. pilsbryi,

L. cardinalis, and

L. zonatus) formed a monophyletic clade (98% of bootstrap replicates). Within the

L. zonatus species group,

L. cardinalis and

L. pilsbryi were most closely related (86% bootstrap replicates), followed by

L. zonatus as expected (Dowling & Naylor, 1997; Mayden, 1988). However, among morphologically identified

L. zonatus populations, the

L. zonatus mtDNA haplogroup was only found in specimens from a portion of its range, in the Black/Current River drainage (

Table 2,

Figure 2a).

The cornutus group excluding L. cerasinus (ie. L. cornutus, L albeolus, and L. chrysocephalus) formed a second monophyletic clade (95% of bootstrap replicates). Luxilus cerasinus was sister to the rest of the cornutus group, though without bootstrap support. There were two mtDNA lineages within the cornutus group, one contained the L. cornutus mtDNA lineage including L. albeolus (100% of bootstrap replicates) while the other contained the L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineage (100% of bootstrap replicates).

Comparison of mtDNA results with morphological species assignments identified considerable introgression among these taxa. A well-defined mtDNA lineage of morphologically identified

L. zonatus (100% of bootstrap replicates) was nested within the range-wide

L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineage, indicating that this distinct lineage (hereafter ‘introgressed

L. zonatus’) resulted from mitochondrial introgression from

L. chrysocephalus into

L. zonatus. These morphologically identified introgressed

L. zonatus were from the St. Francis, Meramec, Gasconade, and Osage river drainages. Most individuals sampled from these populations exhibited the introgressed

L. zonatus mtDNA haplogroup (

Table 2). The paraphyletic

L. chrysocephalus range-wide mtDNA clade, exclusive of introgressed

L. zonatus, exhibited nucleotide diversity (

π) of 0.033. Nucleotide diversity for the monophyletic introgressed

L. zonatus lineage was nearly an order of magnitude lower at 0.004.

The

L. cornutus mtDNA haplogroup also exhibited evidence of introgression as previously reported (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995). Sampled populations of morphologically identified

L. chrysocephalus from drainages throughout the northern Ozark Highlands, as well as the White River drainage in the southern Ozark Highlands all exhibited a monophyletic clade of introgressed

L. cornutus mtDNA (98% support, known hereafter as ‘introgressed

L. chrysocephalus’) (

Table 2,

Figure 2b) and were the sister lineage to a range-wide

L. cornutus clade. The range-wide

L. cornutus and introgressed

L. chrysocephalus clades appeared reciprocally monophyletic, though with lower bootstrap support (86%) and small sample size for the

L. cornutus clade exclusive of the introgressed

L. chrysocephalus clade. The

L. cornutus clade exhibited nucleotide diversity of 0.010 compared to 0.006 for the introgressed

L. chrysocephalus clade. Samples of morphologically identified

L. chrysocephalus taken from the St. Francis River and Whitewater River, exhibited range-wide

L. chrysocephalus haplotypes while the Little St. Francis River sample included both range-wide

L. chrysocephalus and introgressed

L. zonatus haplotypes (

Table 2,

Figure 2b).

Among all sampled

L. zonatus individuals, the only ones that did not exhibit the

L. zonatus haplotype or the here-defined introgressed

L. zonatus haplotype were one individual in the Little Piney, a tributary of the Gasconade River, which exhibited an introgressed

L. chrysocephalus haplotype, and one

L. zonatus individual from the Little St. Francis River exhibiting an

L. chrysocephalus haplotype (

Table 2,

Figure 2a).

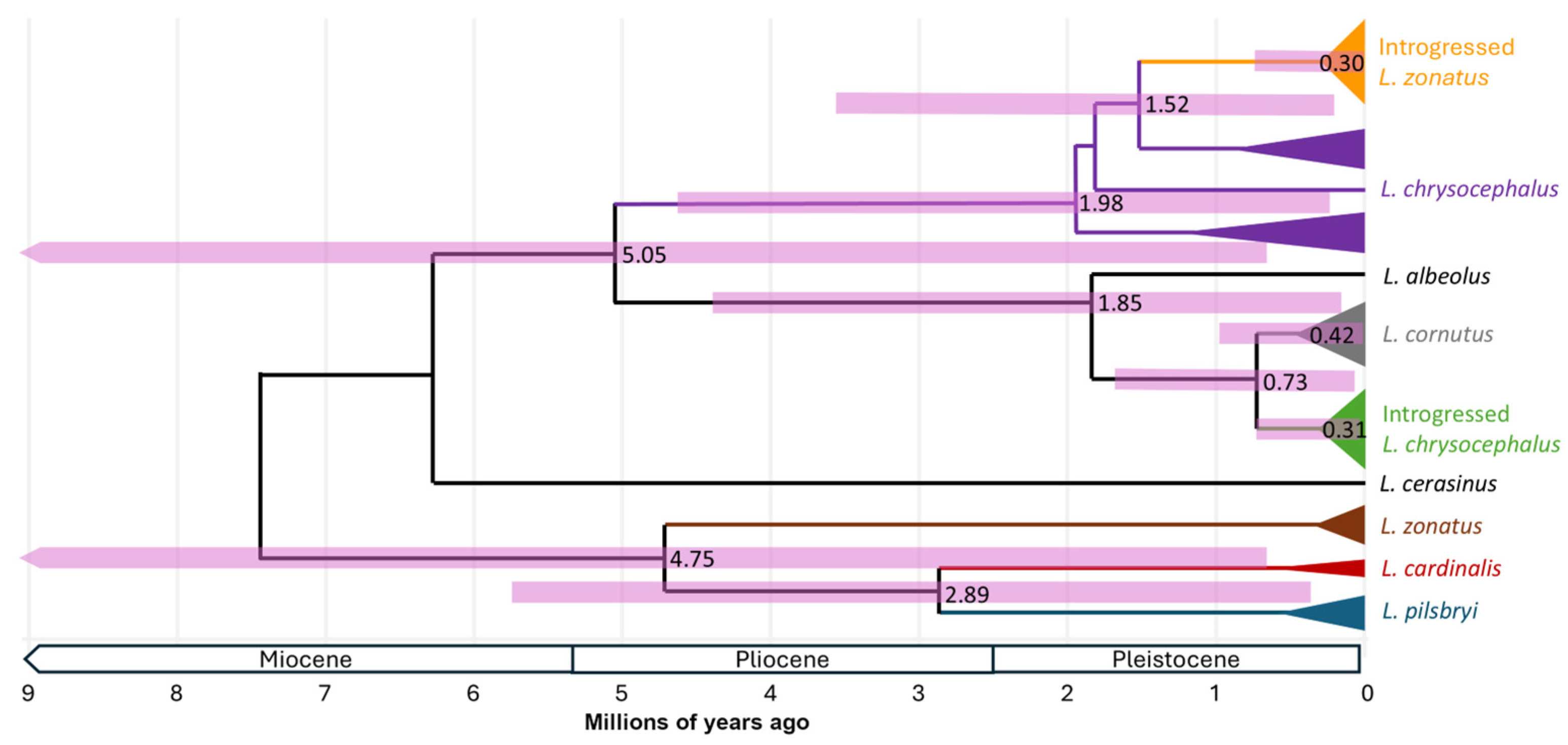

A calibrated phylogeny (

Figure 3) exhibited very large HPD confidence intervals in part due to calibration uncertainty built into the analysis. Nevertheless, confidence intervals placed the coalescent ages of most clades of interest within the Pleistocene (2.6 to 0.01 Ma). Our analysis placed the most likely age of the most recent shared ancestor between

L. cornutus and

L. chrysocephalus as pre-Pleistocene, at 5.05 Ma (0.61 - 11.77 Ma), and the

L. zonatus group (

L. zonatus,

L. pilsbryi,

L. cardinalis) at 4.75 Ma (0.59-11.07) (

Figure 3). The coalescent age of all samples in the

L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineage was 1.98 Ma (0.24 – 4.62 Ma), and the introgressed

L. zonatus clade within the

L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineage was 0.30 Ma (0.03 – 0.72 Ma). Nucleotide divergence (

Dxy) between the introgressed

L. zonatus clade and the next most closely related

L. chrysocephalus haplotype was 0.049 with an estimated age of 1.52 Ma (0.16-3.57 Ma). The age of the ancestor of the

L. cornutus and introgressed

L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineage (i.e. excluding

L. albeolus) was 0.73 Ma (0.07 – 1.72 Ma), with an age for the nested range-wide

L. cornutus clade estimated at 0.42 Ma (0.04 –1.02 Ma), and the introgressed

L. chrysocephalus clade estimated at 0.31 Ma (0.03 – 0.74 Ma), respectively.

4. Discussion

Discordant mitonuclear introgression has been widely documented in many organisms (Bonnet et al., 2017; Hill, 2019; Sloan et al., 2017; Toews & Brelsford, 2012). The features that make our study exceptional are first that mitogenome replacement appears to have occurred twice in succession involving three congeneric shiner species. Second, the ranges of impacted populations in the two affected species are largely congruent and cover multiple isolated drainages that span the northern and eastern Ozark Highlands. The phylogeographic patterns of mitogenome introgression of both L. chrysocephalus and L. zonatus require at least two separate incidences of mitonuclear introgression that are Pleistocene in age, leading to mitogenome replacement in ancestral populations of both species. The broad, congruent geographic overlap of impacted populations, involving numerous Ozark Highland drainages, may reflect the impact of shifting distributions of both species associated with Pleistocene glacial cycles, and coincident with Ozark Highlands geomorphological processes.

Glaciation in North America west of the present day Mississippi River valley was marked by the Laurentide Ice Sheet advancing as far south as the vicinity of the Missouri River Valley at the northern edge of the unglaciated Ozark Highlands. Five glacial advances occurred in this region prior to the Illinoian stage at approximately 2.4, 1.3, 0.8, 0.4, and 0.2 Ma (Rovey & Balco, 2011). These events modified the course of rivers in the region, pushing the range of affected species southward (Robison, 1986). Periglacial lakes along the glacial front would have increased in size as glaciers melted. This would have also increased connection of periglacial lakes along the glacial front, and overflow of meltwater may have allowed for east-west dispersal of fishes along the northern border region of the Ozark Highlands (Robison, 1986).

The major drainages of the Ozark Highlands radiate out of the Salem Plateau. Biogeographically, drainages north of the Salem Plateau (e.g. Osage, Gasconade, Meramec) have similar ichthyofaunal species assemblages that differ in notable respects from drainages south of the Salem Plateau (e.g. St. Francis, Black, White). These biogeographic differences are evident in some Leuciscids (Campostoma spp., Cyprinella spp., Notropis spp.), Centrarchids (Ambloplites spp., Lepomis spp.), Ictalurids (Noturus spp.) (Pflieger, 1997), and intraspecific phylogeography of the Etheostoma caeruleum complex (Ray et al., 2006). There is also evidence that connections occurred occasionally between drainages that were otherwise isolated by the Salem Plateau. A population genetic study of the topminnow, Fundulus olivaceus, identified gene flow between the Big and St. Francis rivers, the Meramec and Black rivers, the Big Piney and North Fork rivers, and the Meramec and Gasconade rivers (Duvernell et al., 2019). Study of fluvial geomorphology in the Ozark Highlands offers evidence that headwaters on opposite sides of the Salem Plateau have commingled historically through numerous stream capture events (Beeson et al., 2017) creating opportunities for faunal exchanges among drainages.

The L. zonatus species group (L. cardinalis, L. pilsbryi, and L. zonatus) diversified in isolated drainages, likely beginning in the Pliocene (common ancestor estimated here at 4.7 Ma), and the phylogeographic distribution of these three species is consistent with their origin in the southern Ozark Highlands followed by a range expansion of L. zonatus into the more northern drainages within its range. Those northern L. zonatus populations appear monophyletic for the introgressed mitogenome acquired from L. chrysocephalus. Among L. zonatus populations, mitogenome introgression has impacted at least four of the five major Ozark drainages encompassed by the extant species distribution such that, range-wide, far more L. zonatus individuals exhibit introgressed than non-introgressed mitogenomes. The distribution of mitogenome replacement in northern L. zonatus populations is consistent with massive introgression predicted by an invasion-with-hybridization model driven by demographic inequality at a northward invasion front (Currat et al., 2008). According to this prediction, as L. zonatus expanded its range into eastern and northern portions of the Ozark Highlands where L. chrysocephalus was already present, the demographic inequality alone between resident and invading populations could have been sufficient to drive asymmetric mtDNA introgression (Currat et al., 2008; Wielstra & Arntzen, 2012). The reduced nucleotide diversity, and monophyly of the introgressed L. zonatus clade relative to other range-wide L. chrysocephalus haplotypes may indicate that this mitogenome replacement event coincided with a founder event initially within a small geographic region (e.g. within one drainage) and then expanded into other drainages through continued L. zonatus range expansion. The broad extant syntopy of L. zonatus and L. chrysocephalus throughout the Ozark Highlands suggests a northward expansion of L. zonatus without competition or species replacement.

The age of the split between L. cornutus and L. chrysocephalus is similarly dated to the Pliocene (5.05 Ma). With a northern L. cornutus range that was almost completely formerly glaciated, the presence of introgressed L. cornutus mitogenomes in Ozark L. chrysocephalus populations provides evidence for range overlap within or in the vicinity of the Ozark Highlands at least sometime during the Pleistocene (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995). The divergence between introgressed haplotypes found in Ozark L. chrysocephalus and the range-wide L. cornutus species haplogroup is dated to approximately mid-late Pleistocene (0.73 Ma). Evidence that hybrid introgression resulted in L. chrysocephalus mitogenome replacement from an L. cornutus donor spans all drainages originating in the Ozark Highlands, with most drainages appearing monophyletic for the introgressed haplogroup, and only drainages in the southeastern Ozark Highlands (Black, St. Francis, and Whitewater Rivers) exhibiting predominantly non-introgressed L. chrysocephalus mitogenomes (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995).

Our phylogenetic analysis shows that, after introgression, range-wide L. cornutus and introgressed Ozark L. chrysocephalus populations achieved reciprocal monophyly. The similar levels of nucleotide diversity between range-wide L. cornutus and introgressed Ozark L. chrysocephalus suggests that an L. cornutus range-wide expansion was similarly Pleistocene in age and occurred on a similar time frame to when the Ozark L. chrysocephalus introgression event occurred. The relatively limited range-wide nucleotide diversity in the northerly distributed L. cornutus compared to the more southerly distributed L. chrysocephalus is consistent with contrasting and disproportionate impacts of Pleistocene glaciation on these species in their respective extant latitudinal distributions.

The notable feature of these overlapping patterns of introgression is that in multiple drainages where L. zonatus appears monomorphic for an introgressed haplogroup from an L. chrysocephalus donor, sympatric L. chrysocephalus populations appear monomorphic for a different introgressed haplogroup from an L. cornutus donor. This dual mitogenome replacement pattern was observed in all drainages north of the Salem Plateau, including all samples in the Osage, Gasconade and Meramec River drainages. The coalescent ages of the introgressed L. chrysocephalus and L. zonatus haplogroup clades are both pre-Illinoian late Pleistocene, and with essentially the same age estimates (310 and 297 kya, respectively), suggesting that introgressed populations of both species may have established nearly concurrently via either range expansions or gene flow. However, L. zonatus introgression would have had to preceded L. chrysocephalus introgression or else introgressed L. zonatus populations would exhibit L. cornutus-lineage haplotypes instead of L. chrysocephalus-lineage haplotypes.

The phylogeographic distribution of mitogenome replacement events across multiple isolated drainages may suggest a deterministic driver operating similarly in separate drainages throughout the Ozark Highlands. However, the concurrent prevalence of introgressed mitogenomes in populations of both L. chrysocephalus and L. zonatus presents challenges to the invocation of natural selection as a driving factor. If mitogenome replacement was prevalent across multiple Ozark drainages because natural selection favored introgression of locally adapted mitogenomes in both species, then this does not account for why natural selection would favor different non-native mitogenomes in sympatric populations of each species. Similarly, if the driver of selection favoring introgressed mitogenomes was to alleviate some form of accumulated mutation load, as might have been caused by founder effects resulting from shifting ranges driven by glacial cycles, then that would not address the multi-drainage pattern of introgression or explain why introgressed mitogenomes were more fit than native mitogenomes in both species. The alternative explanation for the broad distribution of introgressed mitogenomes in both Luxilus species across very similar geographic areas that encompass most of the same Ozark drainages is range expansions and drainage invasions that could have occurred repeatedly for both species. The shared history of mitogenome haplogroups points to a complicated history of hybridization and introgression between these species. This calls for a better understanding of the phylogeographic histories of both species that will only be possible with further sampling and nuclear genome data.

Distributions of mitochondrial haplogroups between

L. zonatus and

L. chrysocephalus are further complicated in the St. Francis River drainage in the southeastern Ozark Highlands. The

L. chrysocephalus sampled in the St. Francis River drainage in this study exhibited exceptional mitochondrial sequence diversity that reflected the entire range-wide mitogenome diversity of

L. chrysocephalus (

Figure 1). Results reported here are consistent with those reported by Duvernell and Aspinwall (Duvernell & Aspinwall, 1995) except that the earlier study relied on a PCR-RFLP assay that only resolved

L. cornutus and

L. chrysocephalus mtDNA lineages, and did not delineate differences between the introgressed

L. zonatus haplogroup and all other range-wide

L. chrysocephalus haplotypes.

In the Little St. Francis River, both L. zonatus and L. chrysocephalus were polymorphic for L. chrysocephalus haplotypes, including a predominance of the introgressed L. zonatus haplogroup in both species. The prevalence of the introgressed L. zonatus haplogroup could be indicative of an ancestral polymorphism in the Little St. Francis L. chrysocephalus population that has been shared with L. zonatus through introgressive hybridization. The St. Francis River L. chrysocephalus could be the source of the introgressed L. zonatus haplogroup that subsequently expanded into other Ozark Highland drainages. Alternatively, the shared mitochondrial polymorphisms between L. zonatus and L. chrysocephalus in the Little St. Francis River could indicate more recent, ongoing hybridization between the species. Further sampling within this drainage, with the inclusion of nuclear genetic data, is needed before conclusions can be drawn. Either way, this level of interspecies haplogroup sharing is distinctive within this system and was not encountered to the same extent in any other drainages. In the Osage, Gasconade and Meramec drainages where L. chrysocephalus and L. zonatus are syntopic and both essentially monomorphic for introgressed haplogroups, there is little evidence of recent or ongoing hybridization between the species except for one L. zonatus individual from Little Piney Creek in the Gasconade River drainage that exhibited the introgressed L. chrysocephalus mitogenome.

5. Conclusions

The concurrent patterns of mitogenome introgression among Luxilus species within the Ozark Highlands offer an exceptional example of mitonuclear discordance impacting multiple species and provide unique insights into Pleistocene-era impacts of gene flow and range shifts driven or facilitated by glacial advances and geomorphological processes occurring in the Ozark Highlands during this period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, David Duvernell and Thomas Dowling; Data curation, David Duvernell; Formal analysis, David Duvernell and Abby Wicks; Funding acquisition, David Duvernell and Thomas Dowling; Investigation, David Duvernell, Carson Arnold and Shila Koju; Project administration, David Duvernell; Writing – original draft, David Duvernell; Writing – review & editing, Abby Wicks and Thomas Dowling.

Funding

This research was supported by institutional funds from MST and WSU. Some samples were funded by previous NSF awards to TED.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Missouri University of Science and Technology (No. 182-21, June 2021). Fish specimens were collected under the issuance of a Wildlife Collector Permit from the Missouri Department of Conservation (Permit No. 64265, February 2024).

Data Availability Statement

All DNA sequences are available in GenBank under accession numbers PV549218-PV549283, OR552081, AP012079, EF613564, MG570447, MT667242, NC084090, NC033925, OR552079, and OR492267.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Opportunities for Undergraduate Research Experiences program run in the Experiential Learning Office at Missouri University of Science and Technology for supporting CA and SK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| mtDNA |

Mitochondrial DNA |

| ML |

Maximum Likelihood |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RFLP |

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism |

| HPD |

Highest Posterior Density |

References

- Arnold, M. L. (1997). Natural Hybridization and Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Beeson, H. W., McCoy, S. W., & Keen-Zebert, A. (2017). Geometric disequilibrium of river basins produces long-lived transient landscapes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 475, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, T., Leblois, R., Rousset, F., & Crochet, P. A. (2017). A reassessment of explanations for discordant introgressions of mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. Evolution, 71(9), 2140–2158. [CrossRef]

- Bossu, C. M., & Near, T. J. (2009). Gene trees reveal repeated instances of mitochondrial DNA Introgression in orangethroat darters (percidae: etheostoma). Systematic Biology, 58(1), 114–129. [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R., Vaughan, T. G., Barido-Sottani, J., Duchêne, S., Fourment, M., Gavryushkina, A., Heled, J., Jones, G., Kühnert, D., De Maio, N., Matschiner, M., Mendes, F. K., Müller, N. F., Ogilvie, H. A., Du Plessis, L., Popinga, A., Rambaut, A., Rasmussen, D., Siveroni, I., … Drummond, A. J. (2019). BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Computational Biology, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Carson, E. W., & Dowling, T. E. (2006). Influence of hydrogeographic history and hybridization on the distribution of genetic variation in the pupfishes Cyprinodon atrorus and C. bifasciatus. Molecular Ecology, 15(3), 667–679. [CrossRef]

- Corush, J. B., Fitzpatrick, B. M., Wolfe, E. L., & Keck, B. P. (2021). Breeding behaviour predicts patterns of natural hybridization in North American minnows (Cyprinidae). Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 34(3), 486–500. [CrossRef]

- Currat, M., Ruedi, M., Petit, R. J., & Excoffier, L. (2008). The hidden side of invasions: Massive introgression by local genes. Evolution, 62(8), 1908–1920. [CrossRef]

- Doiron, S., Louis Bernatchez, †, & Blier, P. U. (2002). A comparative mitogenomic analysis of the potential adaptive value of arctic charr mtDNA introgression in brook charr populations (Salvelinus fontinalis Mitchill). Mol. Biol. Evol, 19(11), 1902–1909. https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/19/11/1902/1012463.

- Dowling, T. E., Broughton, R. E., & Demarais, B. D. (1997). Significant role for historical effects in the evolution of reproductive isolation: Evidence from patterns of introgression between the cyprinid fishes, Luxilus cornutus and Luxilus chrysocephalus. Evolution, 51(5), 1574–1583. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, T. E., & Hoeh, W. R. (1991). The extent of introgression outside the contact zone between Notropis cornutus and Notropis chrysocephalus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Evolution, 45(4), 944–956. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, T. E., Hoeh, W. R., Smith, G. R., & Brown, W. M. (1992). Evolutionary Relationships of Shiners in the Genus Luxilus (Cyprinidae) as Determined by Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA. Copeia, 1992(2), 306–322. https://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Dowling, T. E., & Moore, W. S. (1984). Level of Reproductive Isolation between Two Cyprinid Fishes, Notropis cornutus and N. chrysocephalus. Copeia, 1984(3), 617–628. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1445142.

- Dowling, T. E., & Naylor, G. J. P. (1997). Evolutionary Relationships of Minnows in the Genus Luxilus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) as Determined from Cytochrome b Sequences. Copeia, 1997(4), 758–765. https://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Dowling, T. E., & Secor, C. L. (1997). The role of hybridization and introgression in the diversification of animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst, 28, 593–619. www.annualreviews.org.

- Dowling, T. E., Smith, G. R., & Brown, W. M. (1989). Reproductive isolation and introgression between Notropis cornutus and Notropis chrysocephalus (Family Cyprinidae): comparison of morphology, allozymes, and mitochondrial DNA. Evolution, 43(3), 620–634. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A. J., & Rambaut, A. (2007). BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Duvernell, D. D., & Aspinwall, N. (1995). Introgression of Luxilus cornutus mtDNA into allopatric populations of Luxilus chrysocephalus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) in Missouri and Arkansas. In Molecular Ecology (Vol. 4).

- Duvernell, D. D., & Schaefer, J. F. (2014). Variation in contact zone dynamics between two species of topminnows, Fundulus notatus and F. olivaceus, across isolated drainage systems. Evolutionary Ecology, 28(1). [CrossRef]

- Duvernell, D. D., Westhafer, E., & Schaefer, J. F. (2019). Late Pleistocene range expansion of North American topminnows accompanied by admixture and introgression. Journal of Biogeography, 46(9), 2126–2140. [CrossRef]

- Edelman, N. B., & Mallet, J. (2025). Prevalence and Adaptive Impact of Introgression. Annual Review of Genetics. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A. S., Loggins, R., Kumar, S., & Dowling, T. E. (2001). Does nonneutral evolution shape observed patterns of DNA variation in animal mitochondrial genomes? Annual Review of Genetics, 35, 539–566. www.annualreviews.org.

- Gleason, C. A., & Berra, T. M. (1993). Demonstration of Reproductive Isolation and Observation of Mismatings in Luxilus. In Source: Copeia (Vol. 1993, Issue 3).

- Halas, D. (2011). Assessing the prevalence of common patterns and unique events in the formation of biotas: a study of fish taxa of the North American central highlands. University of Minnesota.

- Hedrick, P. W. (2013). Adaptive introgression in animals: Examples and comparison to new mutation and standing variation as sources of adaptive variation. In Molecular Ecology (Vol. 22, Issue 18, pp. 4606–4618). [CrossRef]

- Hill, G. E. (2019). Reconciling the Mitonuclear Compatibility Species Concept with Rampant Mitochondrial Introgression. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 59(4), 912–924. [CrossRef]

- Hubbs, C. L. (1955). Society of Systematic Biologists Hybridization between Fish Species in Nature. Systematic Zoology, 4(1), 1–20.

- MacPherson, N., Champion, C. P., Weir, L. K., & Dalziel, A. C. (2023). Reproductive isolating mechanisms contributing to asymmetric hybridization in Killifishes (Fundulus spp.). Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 36(3), 605–621. [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. (2005). Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. In Trends in Ecology and Evolution (Vol. 20, Issue 5, pp. 229–237). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mayden, R. L. (1988). Systematics of the Notropis zonatus Species Group, with Description of a New Species from the Interior Highlands of North America. Copeia, 5(1), 153–173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1445934?seq=1&cid=pdf-.

- Meagher, S., & Dowling, T. (1991). Hybridization between the cyprinid fishes Luxilus albeolus, L. cornutus, and L. cerasinus with comments on the proposed hybrid origin of L. albeolus. Copeia, 1991(4), 979–991.

- Nevado, B., KoblmÜller, S., Sturmbauer, C., Snoeks, J., Usano-Alemany, J., & Verheyen, E. (2009). Complete mitochondrial DNA replacement in a Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish. Molecular Ecology, 18(20), 4240–4255. [CrossRef]

- Pflieger, W. L. (1997). The Fishes of Missouri (2nd ed.). Missouri Department of Conservation.

- Ray, J. M., Wood, R. M., & Simons, A. M. (2006). Phylogeography and post-glacial colonization patterns of the rainbow darter, Etheostoma caeruleum (Teleostei: Percidae). Journal of Biogeography, 33(9), 1550–1558. [CrossRef]

- Robison, H. W. (1986). Zoogeographic implications of the Mississippi River basin.. In E. H. Hocutt & E. O. Wiley (Eds.), The Zoogeography of North American Freshwater Fishes (pp. 267–285). Wiley and Sons.

- Rovey, C. W. I., & Balco, G. (2011). Summary of Early and Middle Pleistocene Glaciations in Northern Missouri, USA. In J. Ehlers, P. L. Gibbard, & P. D. Hughes (Eds.), Developments in Quarternary Sciences (Vol. 15, pp. 553–561). Elsevier.

- Rozas, J., Ferrer-Mata, A., Sanchez-DelBarrio, J. C., Guirao-Rico, S., Librado, P., Ramos-Onsins, S. E., & Sanchez-Gracia, A. (2017). DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34(12), 3299–3302. [CrossRef]

- Scribner, K. T., Page, K. S., & Bartron, M. L. (2001). Hybridization in freshwater fishes: a review of case studies and cytonuclear methods of biological inference. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 10, 293–323.

- Sloan, D. B., Havird, J. C., & Sharbrough, J. (2017). The on-again, off-again relationship between mitochondrial genomes and species boundaries. Molecular Ecology, 26(8), 2212–2236. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K., Stecher, G., & Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38(7), 3022–3027. [CrossRef]

- Toews, D. P. L., & Brelsford, A. (2012). The biogeography of mitochondrial and nuclear discordance in animals. In Molecular Ecology (Vol. 21, Issue 16, pp. 3907–3930). [CrossRef]

- Wielstra, B. (2019). Historical hybrid zone movement: More pervasive than appreciated. Journal of Biogeography, 46(7), 1300–1305. [CrossRef]

- Wielstra, B., & Arntzen, J. W. (2012). Postglacial species displacement in Triturus newts deduced from asymmetrically introgressed mitochondrial DNA and ecological niche models. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C. C., & Bernatchez, L. (1998). The ghost of hybrids past: Fixation of arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) mitochondrial DNA in an introgressed population of lake trout (S. namaycush). Molecular Ecology, 7(1), 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, Z. D., Douglas, M. R., Chafin, T. K., & Douglas, M. E. (2023). A community genomics approach to natural hybridization. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1999). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).