Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework and Objectives

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Conceptual Scope

- Demonstrated high vocal demand, such as singers, actors, choir members, teachers, or performing arts students, provided they actively engaged in structured vocal tasks within experimental or ecological settings.

- Presented with functional dysphonia (either clinically diagnosed or subclinical), when accompanied by monitored vocal activity and relevant physiological measurements.

- Individuals with chronic cardiovascular conditions (e.g., heart failure), due to the risk of confounding autonomic responses unrelated to vocal activity.

- Studies in which participants did not perform vocalizations, or where voice was used solely as a stimulus (e.g., to elicit stress) without acoustic or physiological analysis.

- Direct autonomic indices: such as HR, HRV, RSA, EDA, BPV, baroreflex sensitivity.

- Indirect markers: such as salivary cortisol, when clearly associated with autonomic regulation and when voice production was a central element of the protocol.

- Excluded studies that reported only general physiological data alone (e.g., HR, respiratory rate) without autonomic interpretation or without a functional analysis of vocal performance.

- Ecological settings such as live performances, oral examinations, or rehearsals.

- Controlled experimental protocols involving structured vocal tasks, provided that both vocal behaviour and autonomic activity were objectively measured and jointly interpreted.

2.3. Search Strategy and Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Variables Collected

- Bibliographic information: authors and year of publication.

- Study design: methodological classification (e.g., experimental, cross-sectional, observational, longitudinal).

- Study population: number of participants, demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex), and vocal profile (e.g., singers, teachers, individuals with functional voice disorders).

- Study objective: main aim or hypothesis related to the relationship between vocal production and autonomic regulation.

- Autonomic and physiological variables: HR, HRV [root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN), low-frequency power (LF), high-frequency power (HF), percentage of successive R–R intervals between normal heartbeats (NN intervals) that differ by more than 50 ms (pNN50), and standard deviation of successive differences (SDSD)]; BPV; pulse pressure (PP); blood pressure (BP); pulse volume amplitude (PVA); systolic blood pressure (SBP); diastolic blood pressure (DBP); mean pressure (MP); RSA; skin conductance response (SCR) or EDA; salivary cortisol; respiration rate.

- Vocal task and context: type of vocalization (e.g., sustained phonation, singing, reading aloud, polyphonic ensemble singing, speech under cognitive load), and whether the task was performed in an ecological or experimental setting.

- Main findings: outcomes related to changes in autonomic markers, voice parameters, or significant correlations reported by the original authors.

- Voice–ANS interplay: how each study described or interpreted the interaction between vocal behaviour and autonomic modulation, whether correlative, functional, or physiological.

3. Results

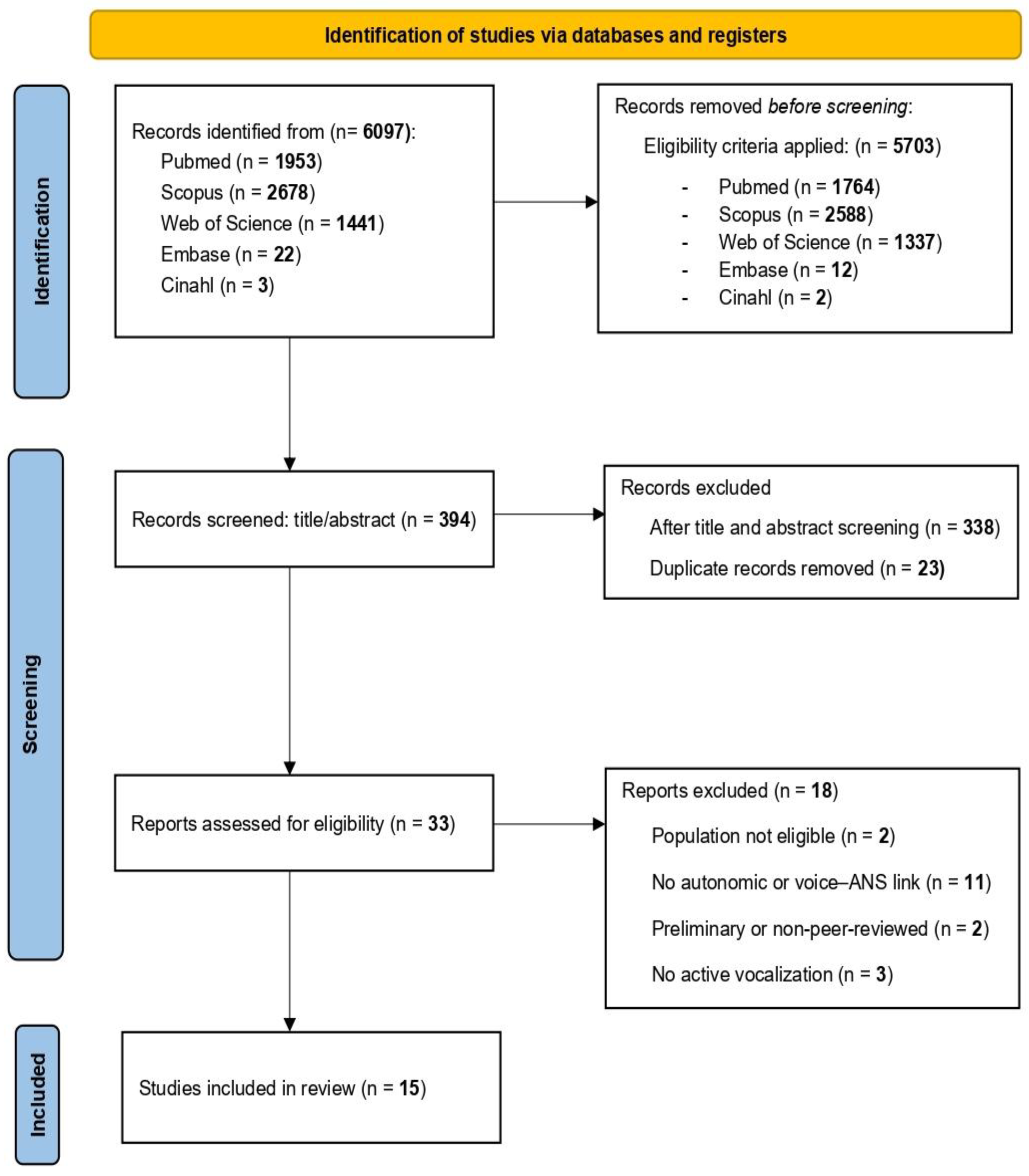

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

3.2. Characteristics and Results of Included Studies

| No. | First author (Year) | Study design | Study population | Study objective | Autonomic variables measured | Vocal context | Main findings | Voice–ANS interplay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Müller & Lindenberger (2011) [16] |

Controlled observational within-subject | n = 12 (11 singers + 1 conductor); adult choir members (Germany) | To examine how choral singing influences interpersonal synchronization of autonomic and respiratory signals, comparing unison with multipart vocal conditions. | HRV synchrony (PSI, ACI, ICI, GC), respiration (PSI, ACI, ICI, GC) | Unison singing, part singing, and canon with eyes open and closed | Respiration and HRV synchronization increased during singing (> 0.15 Hz), strongest in unison (η² = 0.83; 0.59); GC showed conductor influence (p < .0001). | Increased synchronization of respiration and HRV was observed during choral singing, particularly during unison performance. |

| 2 | Bermúdez de Alvear et al. (2013) [17] |

Controlled experimental | n = 14 healthy adults (7 men, 7 women) without known vocal or cardiovascular conditions (Spain) | To determine whether voice F₀ correlates with heart rate and blood pressure during autonomic challenge. | HR, SP, DP, MP | Sustained /æ/ phonation (5 s) duringbaseline and three autonomic tasks: handgrip, cold pressor and arithmetic. | Phonation increased HR and MBP across conditions, with ΔHR exceeding MBP changes. F₀ correlated with HR during phonation (r = .290; p < .001), but not with BP. Mental arithmetic triggered the highest HR and F₀ rise (~13 Hz). | Coupling between F₀ and HR was observed during phonation, with the strongest responses under cognitive load. |

| 3 | Vickhoff et al. (2013) [18] | Controlled experimental | n = 11; healthy 18-year-olds with choral experience (Sweden) | To characterize the autonomic response to vocal tasks with varying respiratory and rhythmic structures. |

HRV (RMSSD, coherence), RSA, HR, SC, temperature | Humming, hymn singing, mantra singing (0.1 Hz) | Mantra: ↑RMSSD (p < 0.01), highest HRV coherence; Hymn: ↑RMSSD (p < 0.05), moderate coherence; Humming: no group synchrony; SC and temp: no change. | HRV coherence and RMSSD increased during structured vocalization at 0.1 Hz, particularly with mantras and hymns, no changes observed with humming. |

| 4 | Pisanski et al. (2016) [19] |

Controlled experimental | n = 34; female undergraduate psychology students (United Kingdom) | To assess whether individual cortisol reactivity predicts changes in voice pitch during academic oral exam stress. | Salivary cortisol | Spontaneous and read speech (oral exam context) | ↑Mean and min F₀ under stress in both tasks (p = .014/.034); cortisol ↑ (+74%) predicted F₀ only under stress (rs = .46/.45); no effect on max F₀ or SD. | Increases in voice pitch during stress were associated with elevated cortisol levels, as observed in both vocal tasks. |

| 5 | MacPherson et al. (2017) [20] | Controlled experimental within-subject | n = 16; healthy young adults (USA) | To analyse the effects of cognitive load during speech on autonomic arousal and vocal acoustics. | SCR, PVA, PP | Oral reading of Stroop stimuli (congruent vs. incongruent conditions) | Cognitive load during speech increased sympathetic arousal (↑SCR, p = .001) and altered voice quality (↑CPP, p = .050; ↓L/H ratio, p = .004) | Changes in voice quality and increased sympathetic arousal were both observed during speech under cognitive stress. |

| 6 | Bernardi et al. (2017) [21] | Controlled crossover experimental | n = 20 healthy adults; no vocal training (Canada) | To examine the cardiorespiratory effects of song singing and toning and clarify whether observed changes stem from vocalization itself or the associated breathing pattern. | HRV (SDNN, LF, HF), HR | Singing of familiar slow songs (Western style) and improvised vocalization of free vowel sounds (toning) | Toning increased HRV (SDNN: p < .001, η²ₚ = 0.70) and LF power (p < .001, η²ₚ = 0.48), while reducing HF power (p < .001, η²ₚ = 0.57), compared to singing. Heart rate rose in both tasks (p = .002, η²ₚ = 0.41). Toning also induced a spontaneous breathing rhythm. | Toning was associated with a spontaneous 0.1 Hz respiratory pattern and enhanced HRV. |

| 7 | Müller et al. (2019) [22] |

Controlled within-subject experimental | n = 12; adults amateur choir members (Germany) |

To characterize the changes in network topology induced by choral singing and their association with HR and HRV as measures of autonomic activity. | HR, HRV (SDNN, RMSSD, LF/HF) | Canon singing in unison (Cun); canon singing in three parts with eyes open (Ceo) and closed (Cec) | In Cun, HR and LF/HF decreased with stronger CFC input and output (r = –0.799; r = –0.667). In Ceo, LF/HF decreased with CFC input (r = –0.576) | Unison singing was associated with increased global connectivity; multipart singing showed greater cardiorespiratory coupling. |

| 8 | Ciccarelli et al. (2019) [23] | Longitudinal observational (ambulatory) | n = 14 adults with NPVH(USA) | To characterize SCR–f₀ SD coupling in patients with NPVH during daily voice use. | EDA (SCR) | Ambulatory speech in daily life | Significant SCR– F₀ SD correlations (p < .05) were predominantly observed at a 2-minute lag in NPVH group. | Sympathetic activity (SCR) and F₀ variability were temporally aligned in NPVH participants during daily voice use. |

| 9 | Ruiz-Blais et al. (2020) [24] | Controlled experimental (within-subjects) | n = 18; non-expert singers (United Kingdom) | To determine whether vocal tasks induce HRV synchrony in non-experts, and if this coupling exceeds the effects of respiration. | HR, RMSSD; HRV inter-dyad coherence (TFC, pTFC) | Synchronized short, synchronized long, and asynchronous short notes. | ↑HRV TFC and RMSSD during long-note vocalizations (p = 0.0039 and p = 0.0002); ↑pTFC (p = 0.0078) after controlling for RSA; no HR change. | Long-note vocalizations increase HRV coherence alongside RSA. |

| 10 | Tanzmeister et al. (2022) [25] | Randomizedcontrolled experimental | n = 101; healthy amateur singers aged 18–44 (Austria) |

To evaluate if paced singing at 0.1 Hz enhances cardiovascular regulation and reduces stress reactivity. |

HR, LF-/HF-HRV, SBP, DBP | Paced singing at 0.1 Hz vs. Spontaneous singing | Paced singing (0.1 Hz): ↑LF-HRV (p < .001, d = 1.66); ↑HR (p < .001, d = 1.23); ↑SBP (p < .001, d = 1.48); no change in HF-HRV. | 0.1 Hz singing increases LF-HRV and sympathetic output. |

| 11 | Lange et al. (2022) [26] |

Experimental within-subject | n = 9; healthy adult professional singers and a male conductor (Germany) |

To test the impact of physical contact on cardiorespiratory synchronization during ensemble singing. | HRV (PSI, ACI, ICI), respiration (PSI, ACI, ICI) | Ensemble singing with and without physical contact | Singing ↑HRV synchronization (PSI η² = 0.568, p = .019); Touch vs. no touch: ↑respiration synchronization with touch (PSI η² = 0.539, p = .024); no touch effect on HRV. | Singing increased HRV synchrony, and physical contact was associated with greater respiratory synchronization. |

| 12 | Abur et al. (2023) [27] |

Prospective observational | n = 12 (6 males, 6 females) healthy older adults (68–78 years of age) (USA) | To assess the impact of cognitive load on autonomic activation and voice acoustics during structured speech tasks. | PVA, PP, SCR | Reading Stroop sentences aloud (congruent vs incongruent conditions) | During vocal tasks under cognitive load, SCR amplitude increased (p < .001) and pulse volume amplitude decreased (p = .025). No significant changes were observed in acoustic measures (CPP, L/H ratio, f₀). | Sympathetic activation was observed during speech under cognitive load, with no significant changes in vocal acoustic parameters. |

| 13 | Szkiełkowska et al. (2023) [28] | Cross-sectional observational | n = 81; 27 operas singers and 54 controls; healthy, no voice complaints (Poland) | To assess whether SEMG and ANS parameters can detect early signs of hyperfunctional dysphonia. | HRV, BVP, EDA | Sustained /æ/ phonation and glissando |

↑SEMG amplitude in subHD (SUB, max = 254 mV, and SCM, max = 201 mV); ↑HRV, ↓BVP, ↑EDA (only in singers) | SubHD shows increased laryngeal tension and altered ANS signals; patterns differed by vocal training. |

| 14 | Scherbaum & Müller (2023) [29] |

Observational study (with experimental component) | n = 3 professional male singers (Georgia) | To investigate heart rate variability synchronization during polyphonic singing. | HRV (RMSSD) | Polyphonic ensemble singing (Georgian tradition) | Two singers (top and middle voices) showed synchronized HRV patterns during singing; bass voice showed less variability and no clear synchrony. | HRV synchronization was observed during the performance of complex traditional polyphony, particularly in the most dynamically active vocal parts. |

| 15 | Kranodębska et al. (2024) [30] | Cross-sectional observational | n = 50 adults: 26 operas singers and 24 controls; all vocally healthy (Poland) | To explore the association between vocal muscle activity and autonomic responses during vocal and non-vocal tasks under emotional load. | HRV (RMSSD, SDNN, SDSD, pNN50, TRI, TINN), HR, EDA, BVP | Free phonation and glissando | Free phonation and glissando, performed under emotional load, in the full sample, showed significant correlations (p < .05) between SUB and CT amplitudes and HRV (SDNN, RMSSD, pNN50, TRI), EDA (entropy, GSR/min) and BVP. | Emotional vocal tasks revealed concurrent modulation of HRV, EDA, and BVP alongside laryngeal muscle activation (CT, SUB). |

4. Discussion

4.1. Autonomic Synchronization During Group Vocalization

4.2. Autonomic Modulation by Type and Structure of Vocalization

4.3. Autonomic Responses to Emotional and Cognitive Vocal Demands

4.4. Vocal Effort, Functional Dysphonia, and Autonomic Signatures

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| PSI | Phase Synchronization Index |

| ACI | Absolute Coupling Index |

| ICI | Integrative Coupling Index |

| GC | Granger Causality |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| MP | Mean Pressure |

| F₀ | Fundamental Frequency |

| RMSSD | Root Mean Square of Successive Differences |

| RSA | Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia |

| SC | Skin Conductance |

| f₀ SD | Standard Deviation of Fundamental Frequency |

| SCR | Skin Conductance Response |

| PVA | Pulse Volume Amplitude |

| PP | Pulse Pressure |

| L/H ratio | Low/High Spectral Ratio |

| SDNN | Standard Deviation of NN Intervals |

| LF | Low-Frequency Power |

| HF | High-Frequency Power |

| CFC | Cross-Frequency Coupling |

| EDA | Electrodermal Activity |

| NPVH | Non-Phonotraumatic Vocal Hyperfunction |

| TFC | Time–Frequency Coherence |

| pTFC | Partial Time–Frequency Coherence |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| CPP | Cepstral Peak Prominence |

| BVP | Blood Volume Pulse |

| SEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| subHD | Subclinical Hyperfunctional Dysphonia |

| CT | Cricothyroid |

| SUB | Submental |

| SCM | Sternocleidomastoid |

| SDSD | Standard Deviation of Successive Differences |

| pNN50 | Percentage of Adjacent NN Intervals Differing by More Than 50 ms |

| TRI | Triangular Index |

| TINN | Triangular Interpolation of NN Interval Histogram |

References

- Chhetri, D.K.; Neubauer, J.; Sofer, E.; Berry, D.A. Influence and interactions of laryngeal adductors and cricothyroid muscles on fundamental frequency and glottal posture control. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 2052–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lã,, F. M.B.; Gill, B.P. Physiology and its impact on the performance of singing. In The Oxford Handbook of Singing, Welch, G., Howard, D.M., Nix, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achey, M.A.; He, M.Z.; Akst, L.M. Vocal hygiene habits and vocal handicap among conservatory students of classical singing. J. Voice 2016, 30, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.; Meneses, R.F.; Lumini-Oliveira, J.; Pestana, P. Associations between teachers’ autonomic dysfunction and voice complaints. J. Voice 2021, 35, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelblanco, L.; Habib, M.; Stein, D.J.; de Quadros, A.; Cohen, S.M.; Noordzij, J.P. Singing voice handicap and videostrobolaryngoscopy in healthy professional singers. J. Voice 2014, 28, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’haeseleer, E.; Claeys, S.; Meerschman, I.; Bettens, K.; Degeest, S.; Dijckmans, C.; et al. Vocal characteristics and laryngoscopic findings in future musical theater performers. J. Voice 2017, 31, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Demerdash, A.M.; Hafez, N.G.; Tanyous, H.N.; Rezk, K.M.; Shadi, M.S. Screening of voice and vocal tract changes in professional wind instrument players. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 4903–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrwein, E.A.; Orer, H.S.; Barman, S.M. Overview of the anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 1239–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, C.H. Basics of autonomic nervous system function. In Low, P.A.; Benarroch, E.E. Handb. Clin. Neurol., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. Physiology and pathophysiology of the autonomic nervous system. Continuum (Minneap. Minn.) 2020, 26, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Taylor, E.W. Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biol. Psychol. 2007, 74, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helou, L.B.; Jennings, J.R.; Rosen, C.A.; Wang, W.; Verdolini Abbott, K. Intrinsic laryngeal muscle response to a public speech preparation stressor: Personality and autonomic predictors. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2020, 63, 2940–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed Yeganeh, N.; McKee, T.; Werker, J.F.; Hermiston, N.; Boyd, L.A.; Cui, A.-X. Opera trainees’ cognitive functioning is associated with physiological stress during performance. Musicae Sci. 2024, 28, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.L.; Stepp, C.E. Effects of cognitive stress on voice acoustics in individuals with hyperfunctional voice disorders. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2023, 32, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Lindenberger, U. Cardiac and respiratory patterns synchronize between persons during choir singing. PLoS ONE 2011, 6(9), e24893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez de Alvear, R.M.; Barón-López, F.J.; Alguacil, M.D.; Dawid-Milner, M.S. Interactions between voice fundamental frequency and cardiovascular parameters. Preliminary results and physiological mechanisms. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2013, 38(1), 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickhoff, B.; Malmgren, H.; Åström, R.; Nyberg, G.; Ekström, S.-R.; Engwall, M.; et al. Music structure determines heart rate variability of singers. Front Psychol 2013, 4, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisanski, K.; Nowak, J.; Sorokowski, P. Individual differences in cortisol stress response predict increases in voice pitch during exam stress. Physiol Behav 2016, 163, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, M.K.; Abur, D.; Stepp, C.E. Acoustic measures of voice and physiologic measures of autonomic arousal during speech as a function of cognitive load. J Voice 2017, 31(4), 504.e1–504.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, N.F.; Snow, S.; Peretz, I.; Orozco Perez, H.D.; Sabet-Kassouf, N.; Lehmann, A. Cardiorespiratory optimization during improvised singing and toning. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Delius, J.A.M.; Lindenberger, U. Hyper-frequency network topology changes during choral singing. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccarelli, G.; Mehta, D.; Ortiz, A.; Van Stan, J.; Toles, L.; Marks, K.; et al. Correlating an ambulatory voice measure to electrodermal activity in patients with vocal hyperfunction. Proc Int Conf Wearable Implant Body Sens Netw 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Blais, S.; Orini, M.; Chew, E. Heart rate variability synchronizes when non-experts vocalize together. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 7–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzmeister, S.; Rominger, C.; Weber, B.; Tatschl, J.M.; Schwerdtfeger, A.R. Singing at 0.1Hz as a resonance frequency intervention to reduce cardiovascular stress reactivity? Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 876344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, E.B.; Omigie, D.; Trenado, C.; Müller, V.; Wald-Fuhrmann, M.; Merrill, J. Intouch: Cardiac and respiratory patterns synchronize during ensemble singing with physical contact. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16, 928563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abur, D.; MacPherson, M.K.; Shembel, A.C.; Stepp, C.E. Acoustic measures of voice and physiologic measures of autonomic arousal during speech as a function of cognitive load in older adults. J Voice 2023, 37(2), 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkiełkowska, A.; Krasnodębska, P.; Mitas, A.; Bugdol, M.; Romaniszyn-Kania, P.; Pollak, A. Electrophysiological predictors of hyperfunctional dysphonia. Acta Otolaryngol 2023, 143(1), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbaum, F.; Müller, M. From intonation adjustments to synchronization of heart rate variability: Singer interaction in traditional Georgian vocal music. Musicologist 2023, 7(2), 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodębska, P.; Szkiełkowska, A.; Pollak, A.; Romaniszyn-Kania, P.; Bugdol, M.N.; Bugdol, M.D.; et al. Analysis of the relationship between emotion intensity and electrophysiology parameters during a voice examination of opera singers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2024, 1, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemakom, A.; Powezka, K.; Goverdovsky, V.; Jaffer, U.; Mandic, D.P. Quantifying team cooperation through intrinsic multi-scale measures: respiratory and cardiac synchronization in choir singers and surgical teams. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.S.; Kales, S.N. Understanding mind-body disciplines: A pilot study of paced breathing and dynamic muscle contraction on autonomic nervous system reactivity. Stress Health 2019, 35, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, A.R.; Schwarz, G.; Pfurtscheller, K.; Thayer, J.F.; Jarczok, M.N.; Pfurtscheller, G. Heart rate variability (HRV): From brain death to resonance breathing at 6 breaths per minute. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlikoff, R.F.; Baken, R.J. The effect of the heartbeat on vocal fundamental frequency perturbation. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1989, 32, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Gutiérrez, J.Á.; de Rojas Leal, C.; López-González, M.V.; Chao-Écija, A.; Dawid-Milner, M.S. Impact of music performance anxiety on cardiovascular blood pressure responses, autonomic tone and baroreceptor sensitivity to a western classical music piano-concert. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1213117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCC | Keywords |

|---|---|

| (P) | "Professional Voice Users", "Teachers", "Singers", "Voice Disorders", "Functional Dysphonia", "Muscle Tension Dysphonia", "Vocal Hyperfunction" |

| (C) | "Voice", "Singing", “Voice production”, “Vocal effort”, “Autonomic Nervous System", "Autonomic Dysfunction", "Autonomic Regulation", "Sympathetic Nervous System", "Parasympathetic Nervous System", "Heart Rate Variability", "HRV", "Heart Rate", "Heartbeat", "Blood Pressure", "Stress Response" |

| (C) | “Structured vocal tasks”, "Singing Ensemble", “Singing performance”, “Spoken tasks under stress”, “Cognitive-emotional vocal conditions”, “Experimental voice protocols” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).