Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

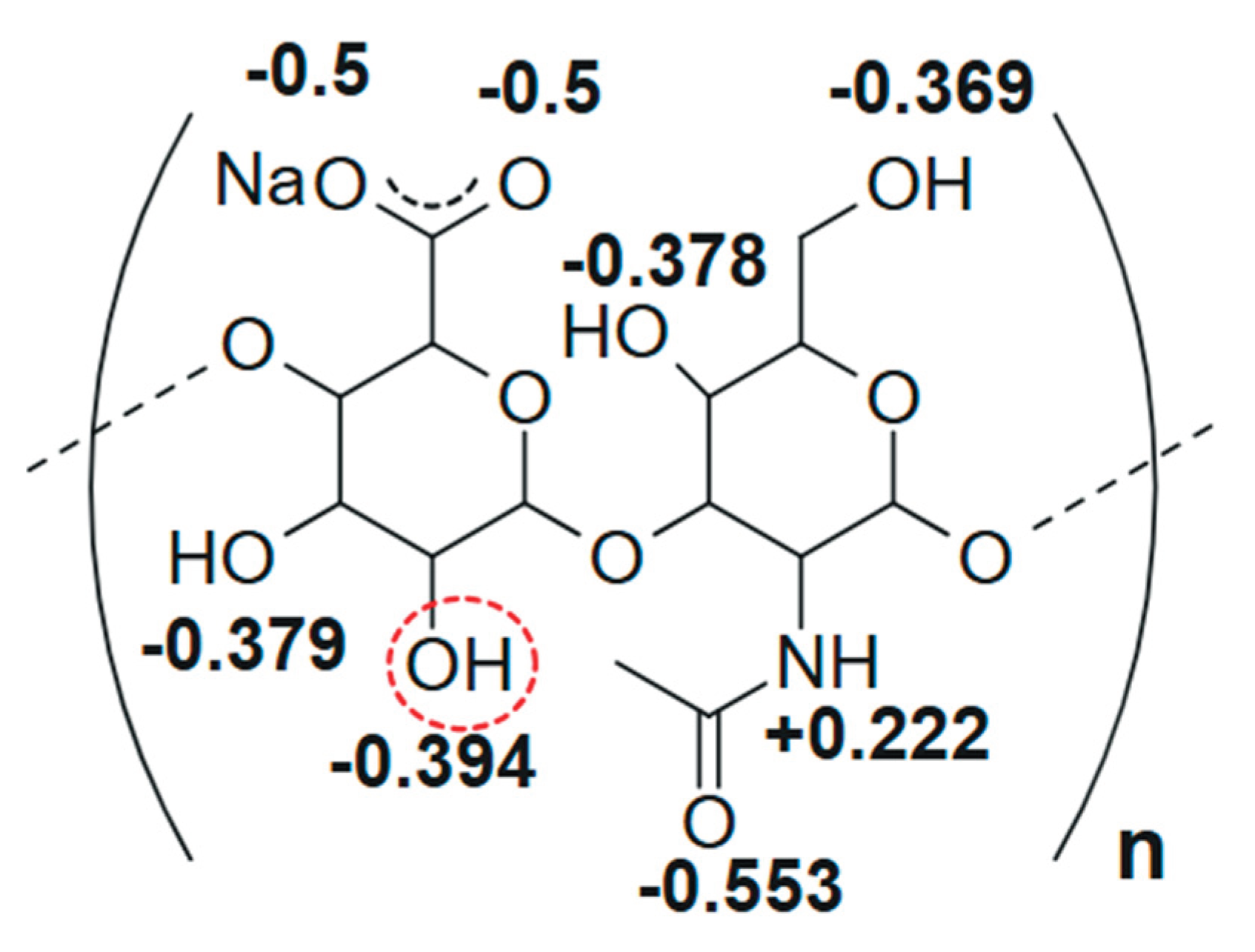

- Spatial tertiary structure of HN formed as a result of the helices interweaving and stabilized by hydrogen bonds between them due to –OH groups [16,21]. These bonds in HNs are weak [64,67,68,69] and can be dynamically destroyed/formed when the solution pH changes [18,56,64,67,68,69], altering the spatial characteristics of HN supramolecular formation over a wide range [70,71,72].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

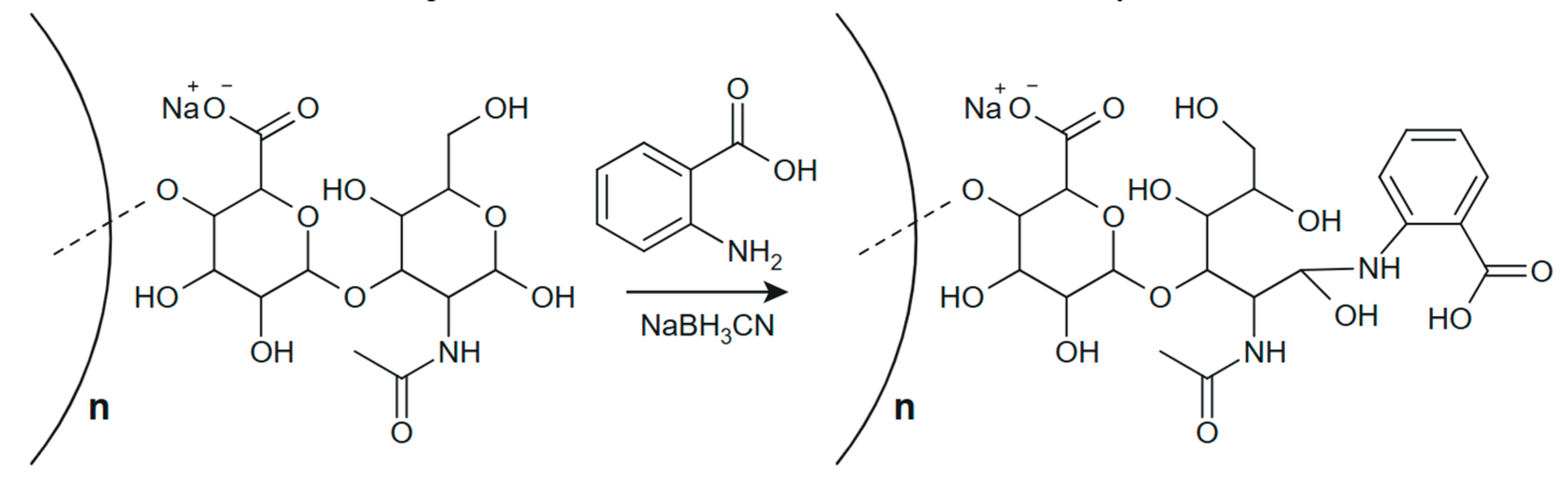

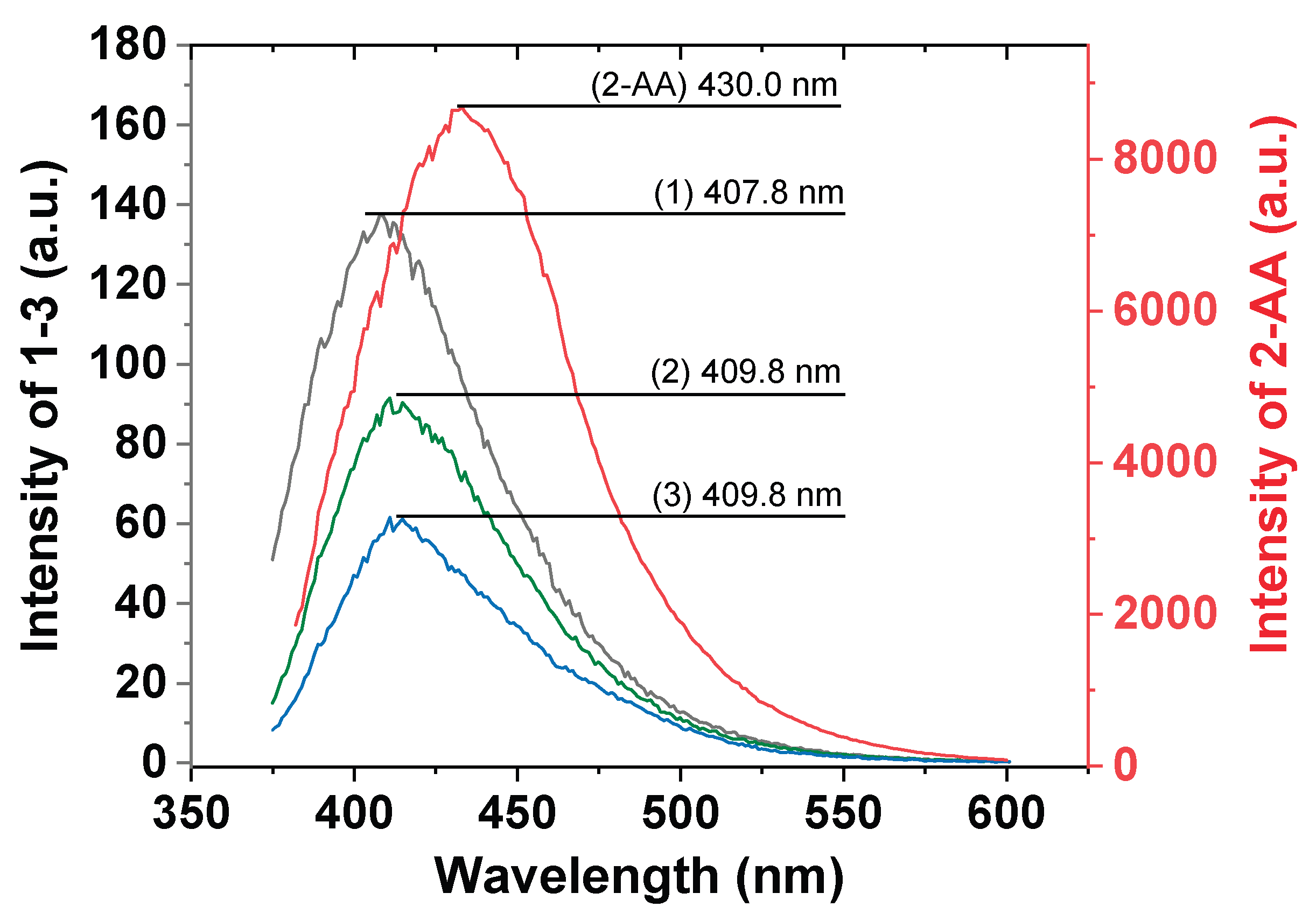

2.2. Conjugation of HN with a Fluorescent Label

2.3. Interaction of HNs with BDDE

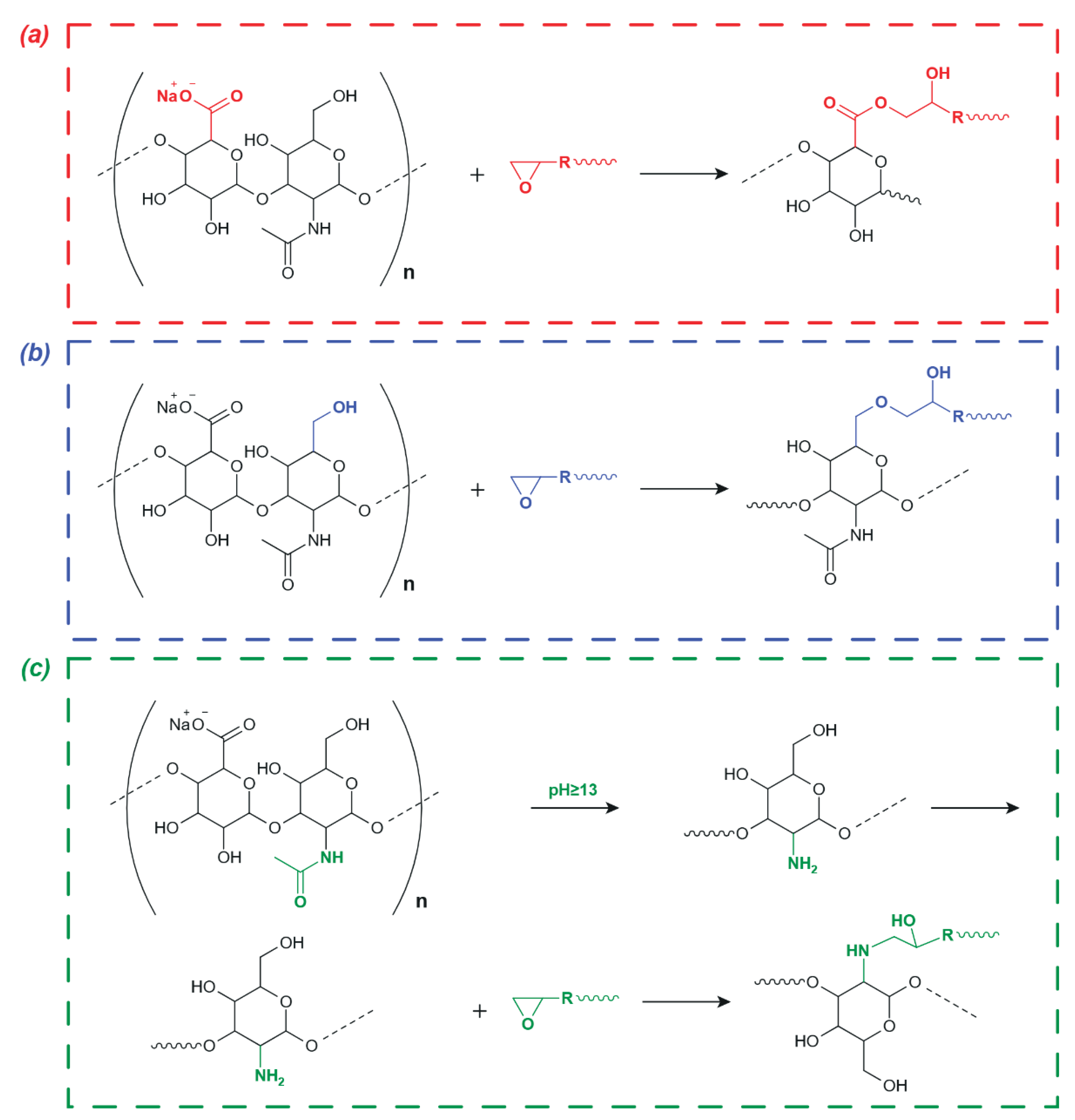

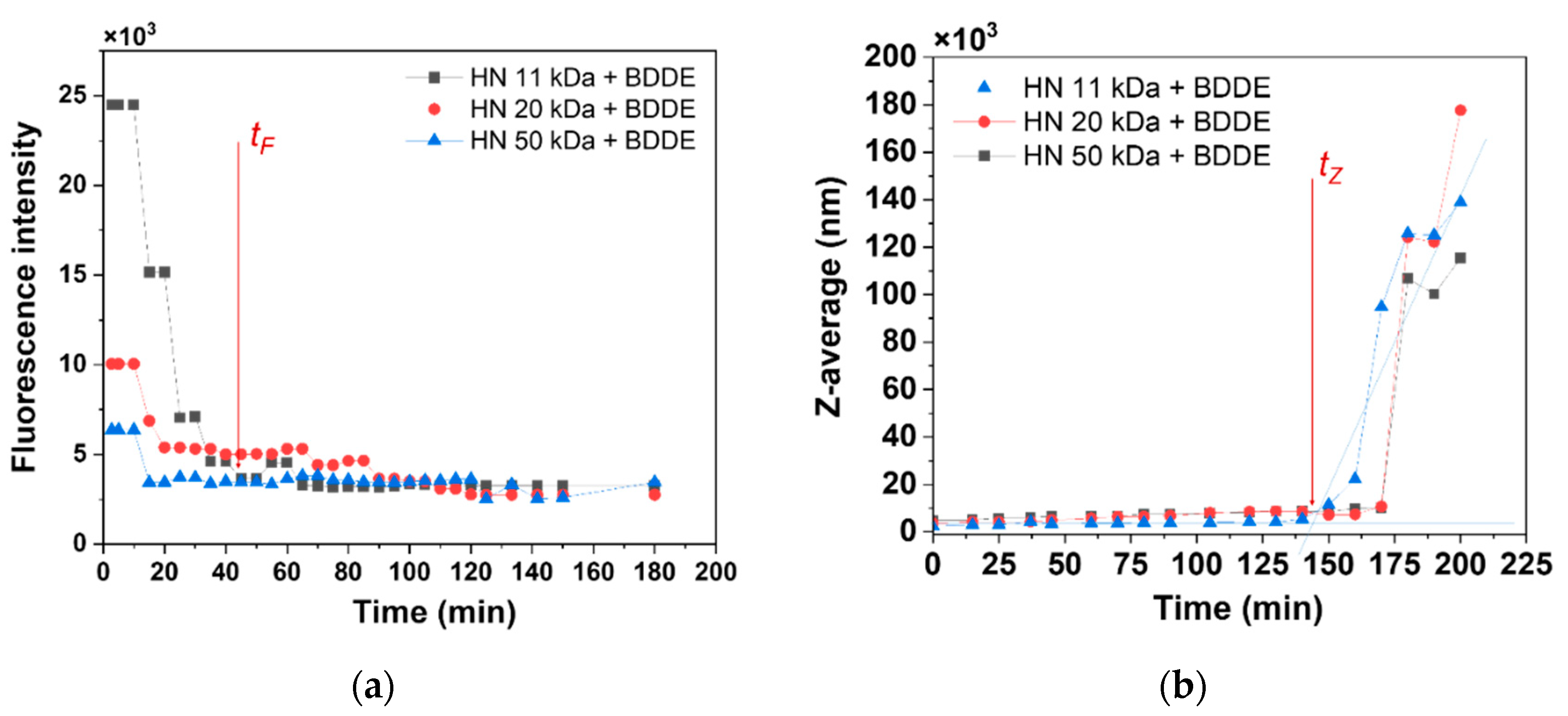

2.4. Model Systems for the HN Modification Studying

2.5. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HN | Hyaluronan |

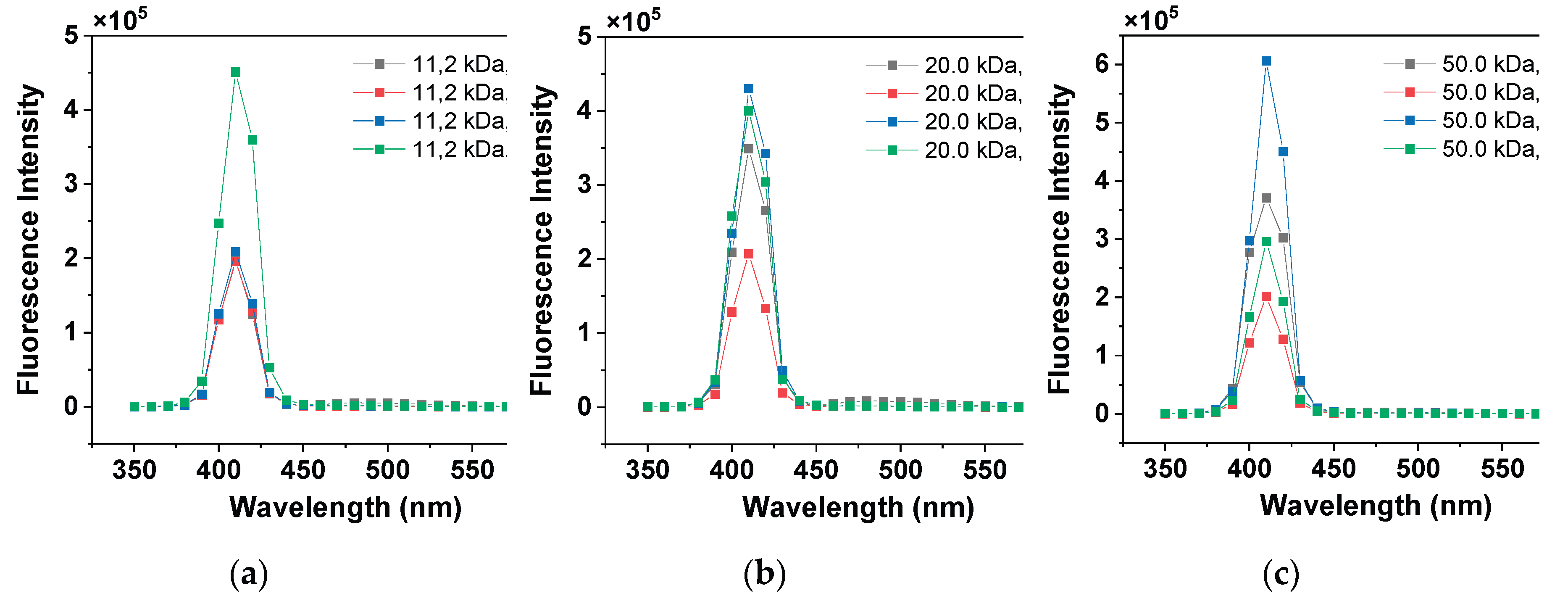

| FS | Fluorescence Spectrophotometry |

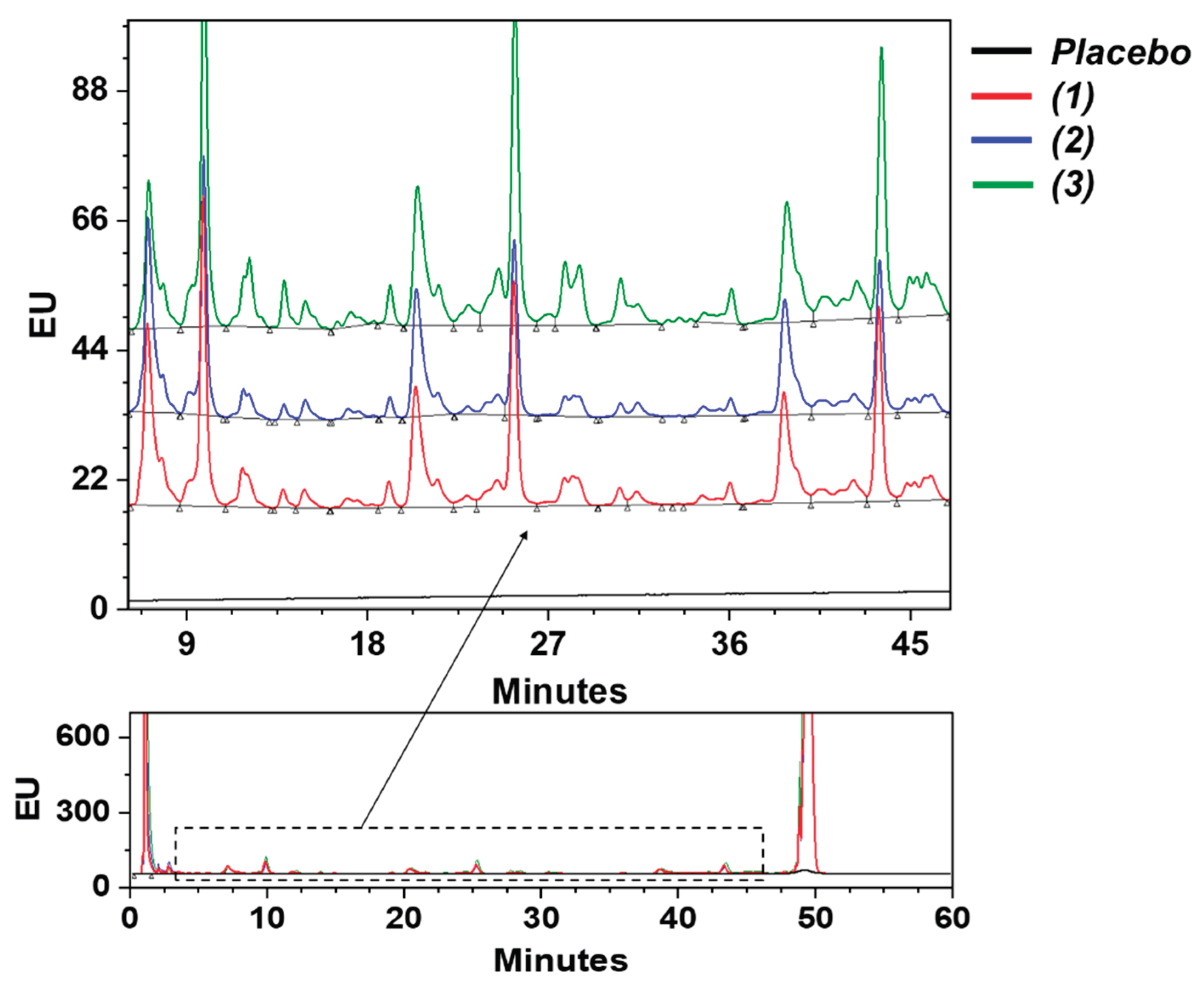

| HILIC HPLC | Hydrophilic Interaction High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

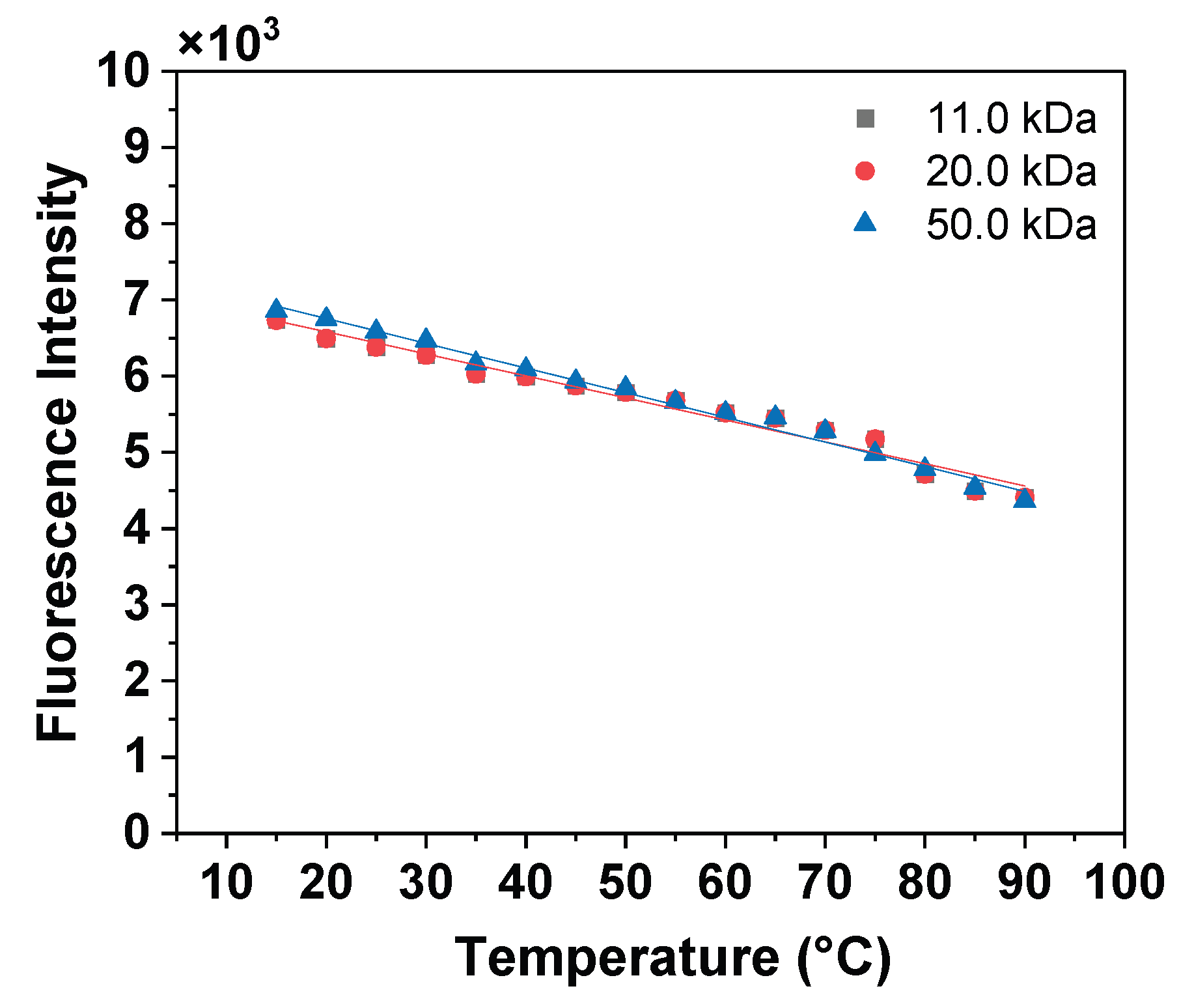

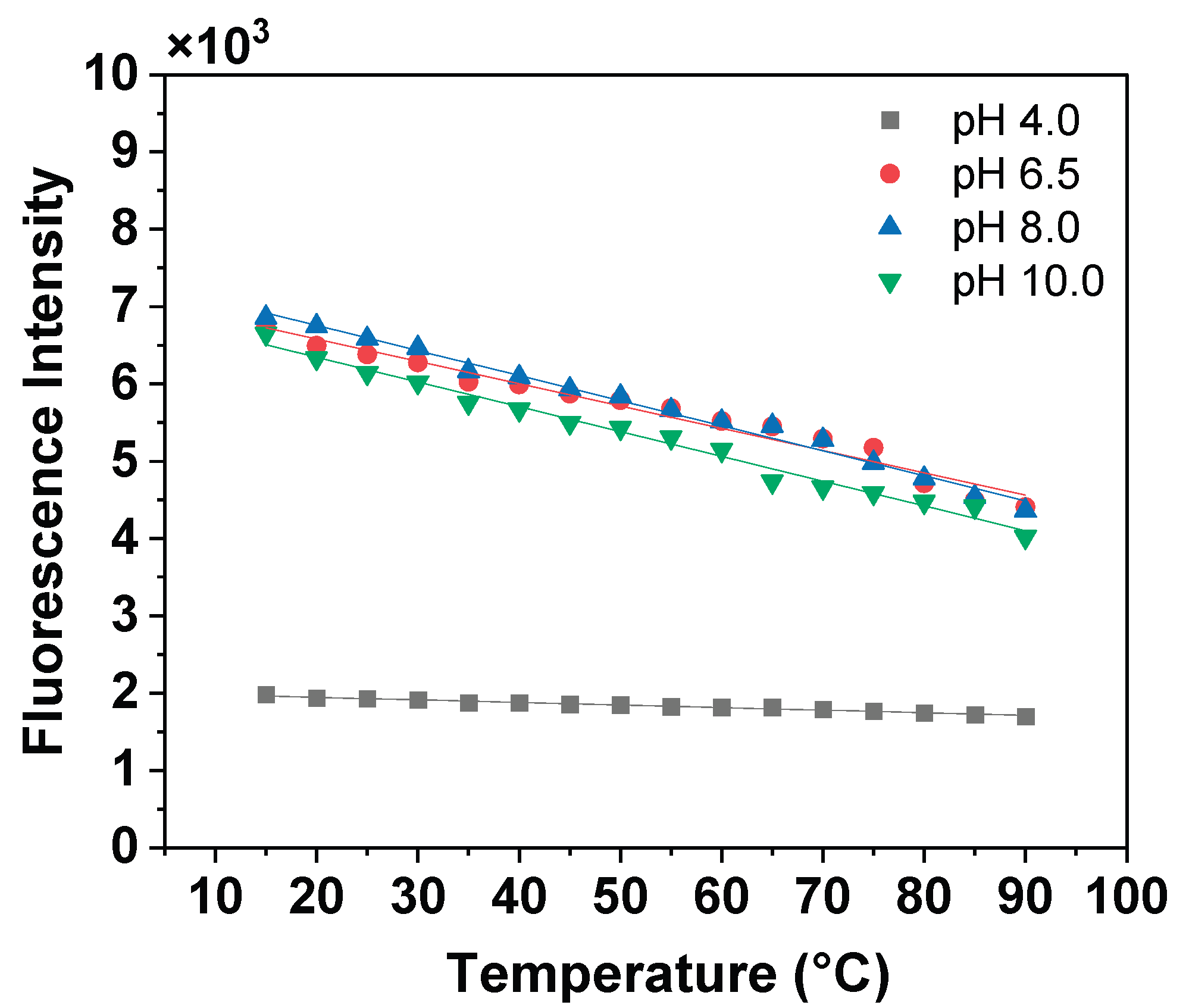

| DSF | Differential Scanning Fluorimetry |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

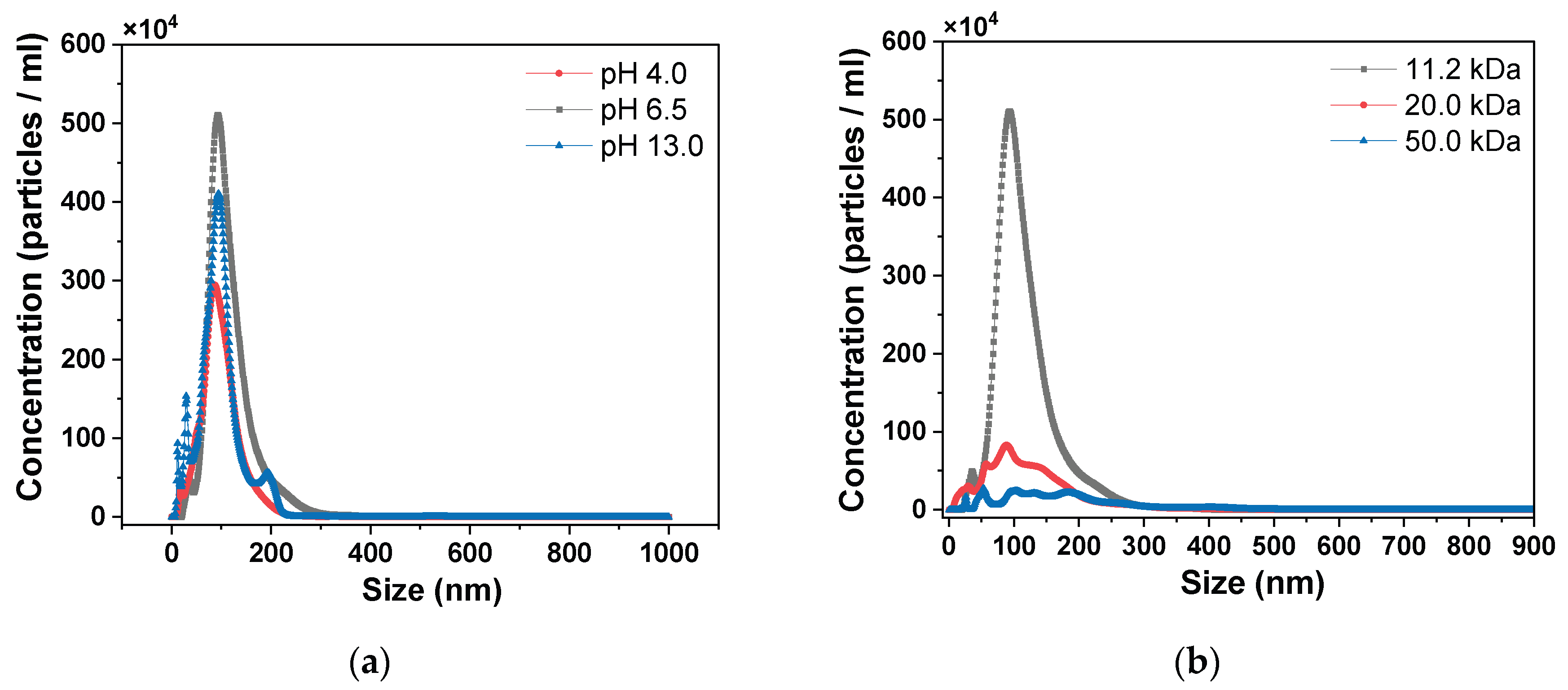

| NTA | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis |

| BDDE | Butane-1,4-diol |

| MM | Molecular Mass |

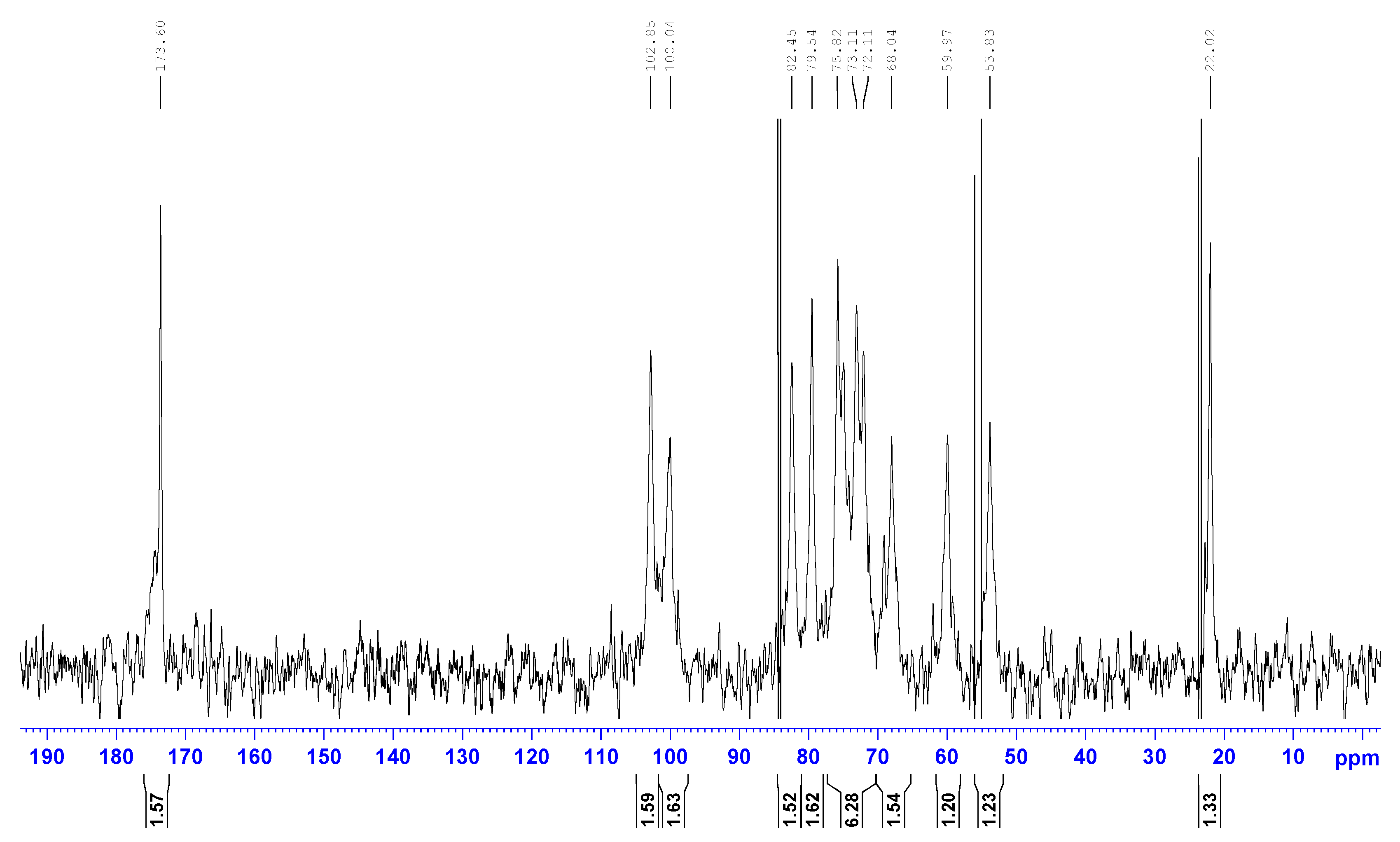

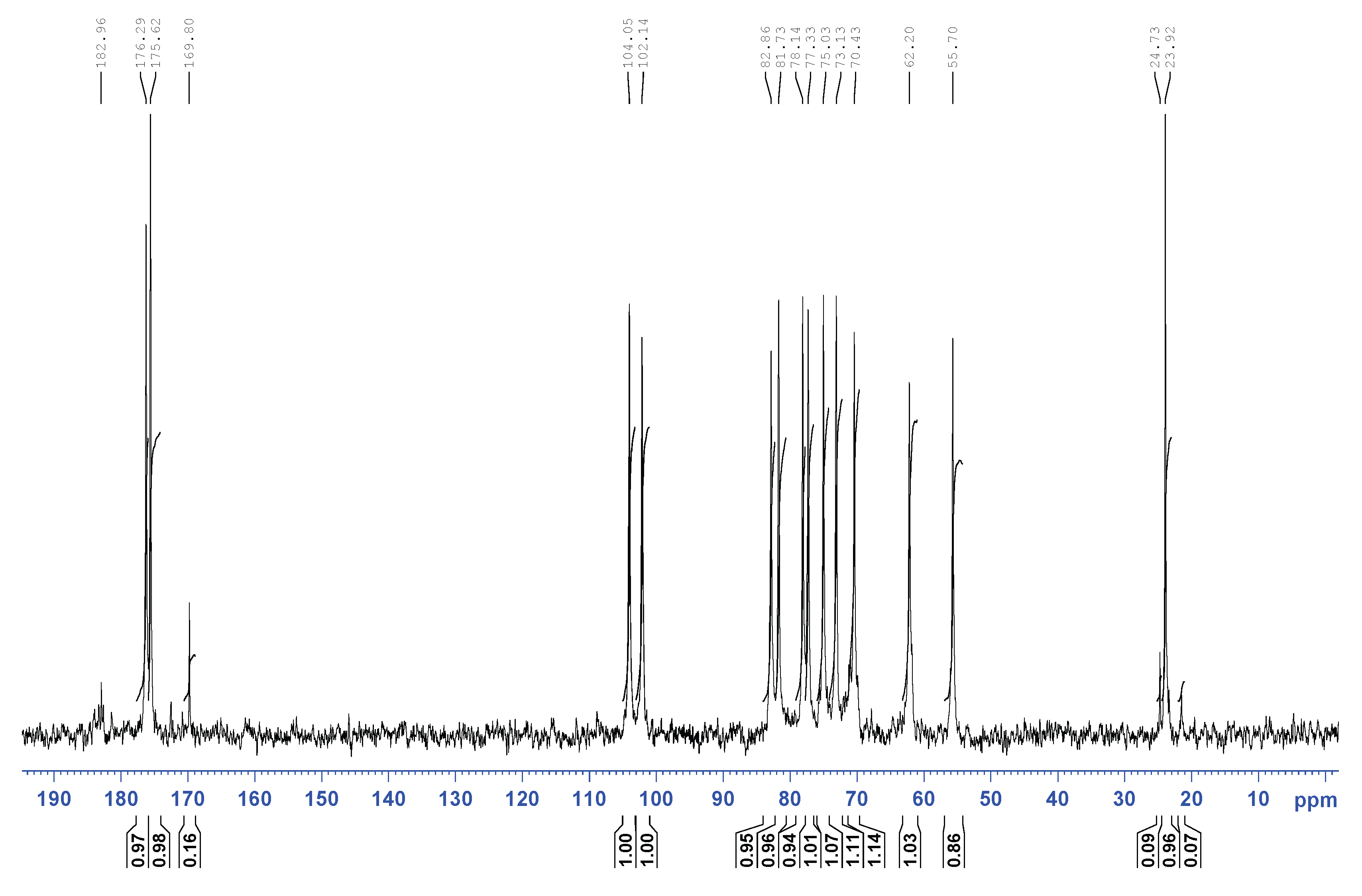

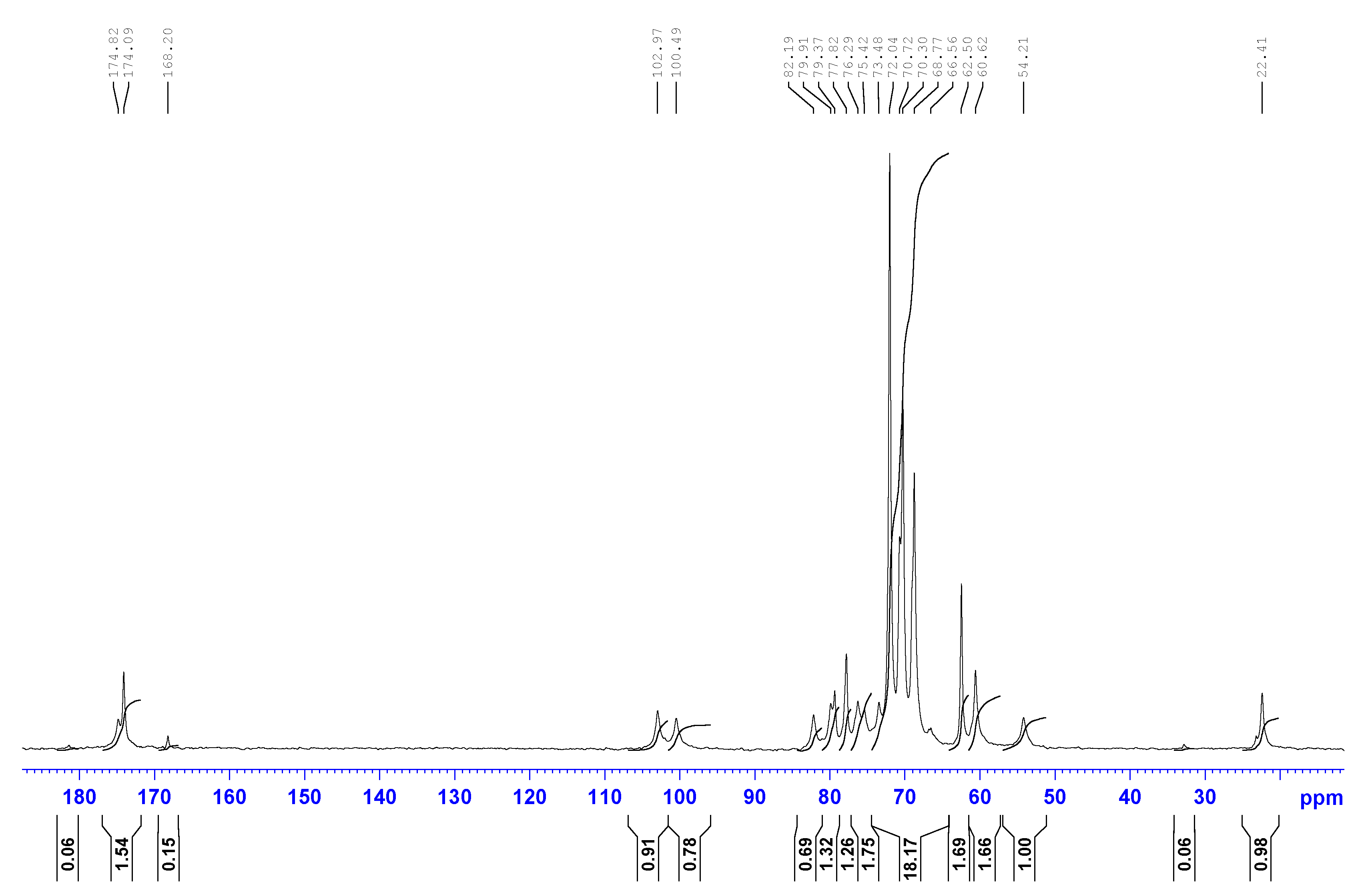

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 2-AA | 2-aminobenzoic acid |

| NaBH3CN | sodium cyanoborohydride |

| 2-AB | 2-aminobenzamide |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

References

- Selyanin, M. A., Boykov, P. Y., & Khabarov, V. N. Hyaluronic Acid: Preparation, Properties, Application in Biology and Medicine. Translated by Felix Polyak, 1st ed., Wiley, 2015.

- Hyaluronan: Structure, Biology and Biotechnology; Passi, A., Ed.; Springer: 2023; 220 p.

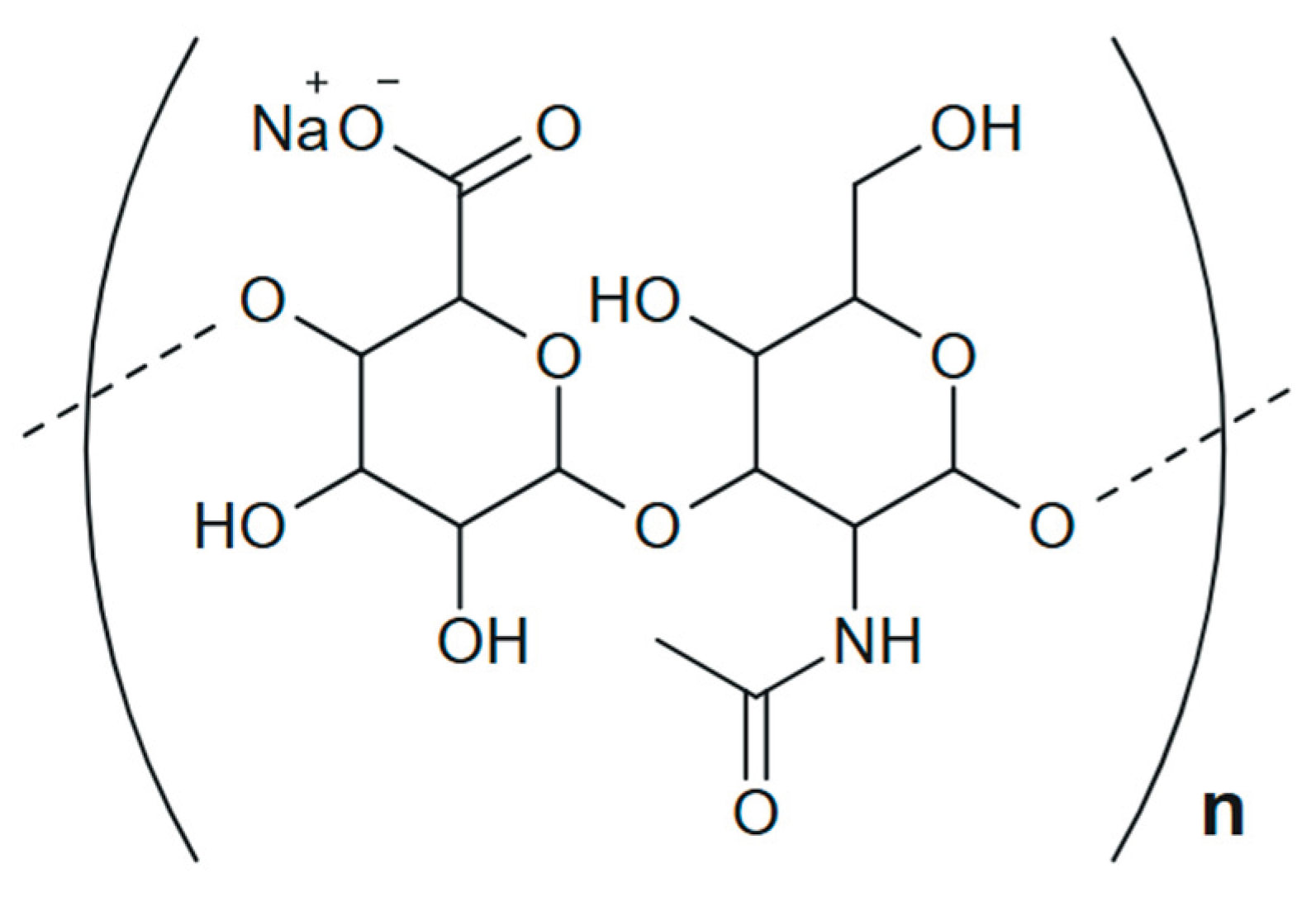

- Rapport, M.; Weissmann, B.; Linker, A.; Meyer, K. Isolation of a Crystalline Disaccharide, Hyalobiuronic Acid, from Hyaluronic Acid. Nature 1951, 168, 996–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, N.; Schiller, J.; Stern, R.; Soltés, L. Role, metabolism, chemical modifications and applications of hyaluronan. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1718–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascall, V.C. Hyaluronan, a common thread. Glycoconj. J. 2000, 17, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hascall, V.C.; Majors, A.K.; De La Motte, C.A.; Evanko, S.P.; Wang, A.; Drazba, J.A.; Strong, S.A.; Wight, T.N. Intracellular hyaluronan: a new frontier for inflammation? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004, 1673, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, G.; Soltés, L.; Stern, R.; Gemeiner, P. Hyaluronic acid: a natural biopolymer with a broad range of biomedical and industrial applications. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, H. G.; Hales, C. A. Chemistry and Biology of Hyaluronan; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, G.; Soltés, L.; Stern, R.; Mendichi, R. Hyaluronic acid: A biopolymer with versatile physicochemical and biological properties. In Handbook of Polymer Research: Monomers, Oligomers, Polymers and Composites, Pethrick, R.A., Ballada, A., Zaikov, G.E., Eds.; Nova Sci. Publishers: New York, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, G.; Soltés, L.; Stern, R.; Schiller, J.; Mendichi, R. Hyaluronic acid: Its function and degradation in in vivo systems. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, T.C. The Chemistry, Biology and Medical Applications of Hyaluronan and Its Derivatives; Portland Press: London, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Balazs, E.A. The introduction of elastoviscous hyaluronan for viscosurgery. In Viscoelastic Materials. Basic Science and Clinical Applications, Rosen, E.S., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, 1989; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Balazs, E.A. Viscoelastic Properties of Hyaluronan and its Therapeutic Use. In Chemistry and Biology of Hyaluronan, Garg, H.G., Hales, C.A., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse, K.P.; Prestwich, G.D. Hyaluronate derivatives in drug delivery. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier. Syst. 1998, 15, 513–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapcík, L., Jr.; Lapcík, L.; De Smedt, S.; Demeester, J.; Chabrecek, P. Hyaluronan: Preparation, Structure, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 2663–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-H.; Jones, S.A.; Forbes, B.; Martin, G.P.; Brown, M.B. Hyaluronan: pharmaceutical characterization and drug delivery. Drug Delivery 2005, 12, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetkov, P.; Hyaluronic acid. Encyclopedia. Polymers and Plastics, Biochemistry. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/2492 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Cowman, M.K. Hyaluronan and hyaluronan fragments. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2017, 74, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetkov, P.; Zakharova, K.; Morozkina, S.; Olekhnovich, R.; Uspenskaya, M. Hyaluronic Acid: The Influence of Molecular Weight on Structural, Physical, Physico-Chemical, and Degradable Properties of Biopolymer. Polymers 2020, 12, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.A.; Hernandez, R.; Alonso, J.M.; Perez-Gonzalez, R.; Saez-Martinez, V. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels crosslinked in physiological conditions: synthesis and biomedical applications. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negas, J.; Bartosikova, L.; Brauner, P.; Kolar, J. Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): a review. Veterinarni Medicina 2008, 53, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, P.; Panfilo, S.; Daga, G.D.; Cortivo, R.; Abatangelo, G. The effect of hyaluronan on CD44-mediated survival of normal and hydroxyl radical-damaged chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2003, 11, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmer, E. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laremore, T.N.; Zhang, F.; Dordick, J.S.; Liu, J.; Linhardt, R.J. Recent progress and applications in glycosaminoglycan and heparin research. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Suner, S.S.; Blake, D.A.; Ayyala, R.S.; Sahiner, N. Antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility of slow-release hyaluronic acid-antibiotic conjugated particles. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 576, 119024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepidi, S.; Abatangelo, G.; Vindigni, V.; Deriu, G.P.; Zavan, B.; Tonello, C.; Cortivo, R. In vivo regeneration of small-diameter (2 mm) arteries using a polymer scaffold. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennaoui, H.; Chouery, E.; Rammal, H.; Abdel-Razzak, Z.; Harmouch, C. Chitosan/hyaluronic acid multilayer films are biocompatible substrate for Wharton’s jelly derived stem cells. Stem Cell Investig. 2018, 20, 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, A.; Fredrickson, G.H. The science of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2008, 10, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, E.M.; Beaumont, M.; Shu, X.Z.; Harvey, A.; Prestwich, G.D.; Horn, K.M.; Gibson, A.R.; Preul, M.C.; Panitch, A. Influence of cross-linked hyaluronic acid hydrogels on neurite outgrowth and recovery from spinal cord injury. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2007, 6, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ave, M.N.; de Almeida Issa, M.C. Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Filler: Physical Properties and Its Indications. In Botulinum Toxins, Fillers and Related Substances. Clinical Approaches and Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology; Issa, M., Tamura, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khabarov, V.N.; Ivanov, P.L. Biomedical applications of hyaluronic acid and its chemically modified derivatives. Geotar-Media: Moscow, Russia, 2020.

- Ponedelkina, I.Yu.; Lukina, E.S.; Odinokov, V.N. Acidic glycosaminoglycans and their chemical modification. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2008, 34, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pouyani, T.; Prestwich, G.D. Functionalized derivatives of hyaluronic acid oligosaccharides: drug carriers and novel biomaterials. Bioconjug. Chem. 1994, 5, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiner, N.; Suner, S.S.; Ayyala, R.S. Mesoporous, degradable hyaluronic acid microparticles for sustainable drug delivery application. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 177, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimojo, A.A.M.; Pires, A.M.B.; Lichy, R.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Santana, M.H.A. The crosslinking degree controls the mechanical, rheological, and swelling properties of hyaluronic acid microparticles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencherif, S.; Srinivasan, A.; Horkay, F.; Hollinger, J. Influence of the degree of methacrylation on hyaluronic acid hydrogels properties. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Synthesis and characterization of a novel hyaluronic acid hydrogel. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2006, 17, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomihata, K.; Ikada, Y. Preparation of cross-linked hyaluronic acid films of low water content. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, N.; Jun, N.; Teruo, O.; Yasuhisa, S. Regulated release of drug microspheres from inflammation responsive degradable matrices of crosslinked hyaluronic acid. J. Control. Release 1993, 25, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, N.; Teruo, O.; Yasuhisa, S. Inflammation responsive degradation of crosslinked hyaluronic acid gels. J. Control. Release 1992, 22, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, D.; Xu, H.; Hu, Y. Synthesis of hyaluronic acid hydrogels by cross-linking the mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid and low-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid with 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether. RSC Adv. 2020, 12, 7206–7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sibani, M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Neubert, R.H.H. Effect of hyaluronic acid initial concentration on cross-linking efficiency of hyaluronic acid – based hydrogels used in biomedical and cosmetic applications. Pharmazie 2017, 72, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, O.; Song, S.J.; Lee, K.J.; Park, M.H.; Lee, S.-H.; Hahn, S.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, B.-S. Mechanical properties and degradation behaviors of hyaluronic acid hydrogels cross-linked at various cross-linking densities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 70, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, N.; Ikada, Y. Mechanism of amide formation by carbodiimide for bioconjugation in aqueous media. Bioconjug. Chem. 1995, 6, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulman, A.M.; Molchanov, V.P.; Balakshina, D.V.; Grebennikova, O.V.; Matveeva, V.G. New nanostructured carriers for cellulase immobilization. Fine Chem. Technol. 2025, 20, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxaire, K.; Braccini, I.; Milas, M.; Rinaudo, M.; Perez, S. Conformational behavior of hyaluronan in relation to its physical properties as probed by molecular modeling. Glycobiology 2000, 10, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.R.; Rees, D.A.; Welsh, E.J. Conformation and dynamic interactions in hyaluronate solutions. J. Mol. Biol. 1980, 138, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkoji, S.; Santra, S.; Tsurkan, M.V.; Werner, C.; Jana, M.; Sahoo, H. Conformational changes of GDNF-derived peptide induced by heparin, heparan sulfate, and sulfated hyaluronic acid – Analysis by circular dichroism spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 2144–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, S.T.; Nizzolo, S.; Freato, N.; Bertocchi, L.; Bianchini, G.; Yates, E.A.; Guerrini, M. Modeling the Detailed Conformational Effects of the Lactosylation of Hyaluronic Acid. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, G.; Liang, Y.; Yan, J.; Koh, C.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Zhou, P. Conformational Entropy of Hyaluronic Acid Contributes to Taste Enhancement. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.; Lee, H.W.; Jang, J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.H. Novel Conformation of Hyaluronic Acid with Improved Cosmetic Efficacy. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, R.; Ogata, S.; Mochizuki, S. Interaction between CD44 and Highly Condensed Hyaluronic Acid through Crosslinking with Proteins. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 121, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amandusova, A.K.; Savel’eva, K.R.; Morozov, A.V.; Shelekhova, V.A.; Persanova, L.V.; Polyakov, S.V.; Shestakov, V.N. Physico-Chemical Properties and Methods of Quantitative Determination of Hyaluronic Acid (Review). Drug Dev. Regist. 2020, 9, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, T.C. Biochemistry of Hyaluronan. Acta Oto-Laryngol. Suppl. 1987, 442, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.E.; Cummings, C.; Brass, A.; Chen, Y. Secondary and Tertiary Structures of Hyaluronan in Aqueous Solution, Investigated by Rotary Shadowing-Electron Microscopy and Computer Simulation. Hyaluronan is a Very Efficient Network-Forming Polymer. Biochem. J. 1991, 274, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Shinoda, K. Complex Formation Between Oppositely Charged Polysaccharides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1976, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guss, J.M.; Hukins, D.W.L.; Smith, P.J.C.; Winter, W.T.; Arnott, S.; Moorhouse, R.; Rees, D.A. Hyaluronic Acid: Molecular Conformations and Interactions in Two Sodium Salts. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 95, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, W.T.; Smith, P.J.C.; Arnott, S. Hyaluronic Acid: Structure of a Fully Extended 3-Fold Helical Sodium Salt and Comparison with the Less Extended 4-Fold Helical Forms. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 99, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, W.T.; Arnott, S. Hyaluronic Acid: The Role of Divalent Cations in Conformation and Packing. J. Mol. Biol. 1977, 117, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J.K.; Atkins, E.D.T. X-Ray Fibre Diffraction Study of Conformational Changes in Hyaluronate Induced in the Presence of Sodium, Potassium and Calcium Cations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1983, 5, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.E.; Heatley, F.; Hull, W.E. Secondary Structure of Hyaluronate in Solution. A 1H-n.m.r. Investigation at 300 and 500MHz in [2H6]dimethyl Sulphoxide Solution. Biochem. J. 1984, 220, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea, I.C.M.; Moorhouse, R.; Rees, D.A.; Arnott, S.; Guss, J.M.; Balazs, E.A. Hyaluronic Acid: A Novel, Double Helical Molecule. Science 1973, 179, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, E.D.; Sheehan, J.K. Hyaluronates: Relation between Molecular Conformations. Science 1973, 179, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.K.; Cozart, D.; Nakanishi, K.; Balazs, E.A. 1H NMR of Glycosaminoglycans and Hyaluronic Acid Oligosaccharides in Aqueous Solution: The Amide Proton Environment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984, 230, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J.K.; Gardner, K.H.; Atkins, E.D.T. Hyaluronic Acid: A Double-Helical Structure in the Presence of Potassium at Low pH and Found Also with the Cations Ammonium, Rubidium and Caesium. J. Mol. Biol. 1977, 117, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnott, S.; Mitra, A.K.; Raghunathan, S. Hyaluronic Acid Double Helix. J. Mol. Biol. 1983, 169, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toffanin, R.; Kvam, B.J.; Flaibani, A.; Atzori, M.; Biviano, F.; Paoletti, S. NMR Studies of Oligosaccharides Derived from Hyaluronate: Complete Assignment of 1H and 13C NMR Spectra of Aqueous Di- and Tetra-Saccharides, and Comparison of Chemical Shifts for Oligosaccharides of Increasing Degree of Polymerisation. Carbohydr. Res. 1993, 245, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.K.; Hittner, D.M.; Feder-Davis, J. 13C-NMR Studies of Hyaluronan: Conformational Sensitivity to Varied Environments. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2894–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.K.; Feder-Davis, J.; Hittner, D.M. 13CNMR Studies of Hyaluronan. 2. Dependence of Conformational Dynamics on Chain Length and Solvent. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ma, D.; Fang, D. Effects of Solution Properties and Electric Field on the Electrospinning of Hyaluronic Acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.G.; Chung, H.J.; Park, T.G. Macroporous and Nanofibrous Hyaluronic Acid/Collagen Hybrid Scaffold Fabricated by Concurrent Electrospinning and Deposition/Leaching of Salt Particles. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabarov, V. On the Question of the Concentration of Hyaluronic Acid in Preparations for Biorevitalization. J. Aes. Med. 2015, 14, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Terbojevich, M.; Cosani, A.; Palumbo, M. Structural Properties of Hyaluronic Acid in Moderately Concentrated Solutions. Carbohydr. Res. 1986, 149, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothner, H.; Wik, O. Rheology of Hialuronate. Acta Oto-Laryngol. Suppl. 1987, 442, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapuler, O.; Galeeva, A.; Sel’skaya, B.; Kamilov, F. Hyaluronan: Properties and Biological Role. Vrach 2015, 2, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boeriu, C.G.; Springer, J.; Kooy, F.K.; Van Den Broek, L.A.M.; Eggink, G. Production Methods for Hyaluronan. Int. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2013, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabarov, V.N.; Boikov, P.Y.; Chizhova, N.A.; Selyanin, M.A.; Mikhailova, N.P. Significance of the Molecular Weight Parameter of Hyaluronic Acid in Preparations for Aesthetic Medicine. J. Aes. Med.. 2009, 8, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R.; Asari, A.A.; Sugahara, K.N. Hyaluronan Fragments: An Information-Rich System. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 85, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimm, H.H.; Jennings, B.R. Study of Hyaluronic Acid Flexibility by Electric Birefringence. Biochem. J. 1983, 213, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, V.; Morando, M.A.; Silipo, A.; Nurisso, A.; Pérez, S.; Imberty, A.; Cañada, F.J.; Parrilli, M.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; De Castro, C. Insights on the Conformational Properties of Hyaluronic Acid by Using NMR Residual Dipolar Couplings and MD Simulations. Glycobiology 2010, 20, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvench, O. Atomic-Resolution Experimental Structural Biology and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Hyaluronan and Its Complexes. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, C.; Jin, L. NMR Characterization of the Interactions Between Glycosaminoglycans and Proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 646808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowman, M.K.; Spagnoli, C.; Kudasheva, D.; Li, M.; Dyal, A.; Kanai, S.; Balazs, E.A. Extended, Relaxed, and Condensed Conformations of Hyaluronan Observed by Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, C.; Korniakov, A.; Ulman, A.; Balazs, E.A.; Lyubchenko, Y.L.; Cowman, M.K. Hyaluronan Conformations on Surfaces: Effect of Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang DP, Abu-Lail NI, Guilak F, Jay GD, Zauscher S. Conformational Mechanics, Adsorption, and Normal Force Interactions of Lubricin and Hyaluronic Acid on Model Surfaces. Langmuir 2008, 24 (4), 1183–1193. [CrossRef]

- Taweechat, P.; Pandey, R.B.; Sompornpisut, P. Conformation, Flexibility and Hydration of Hyaluronic Acid by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 493, 108026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lasanajak, Y.; Song, X. Anthranilic Acid as a Versatile Fluorescent Tag and Linker for Functional Glycomics. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2894–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengattini, S.; Massolini, G.; Rinaldi, F.; Calleri, E.; Temporini, C. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) for the Analysis of Intact Proteins and Glycoproteins. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 174, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry. UNchained LABs. Available online: https://www.unchainedlabs.com/differential-scanning-fluorimetry/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Thaysen-Andersen, M. Analysis of Protein Glycosylation Using HILIC. Merck Sequant Technical Summary, 2010, 1-4.

- Kozlik, P.; Goldman, R.; Sanda, M. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography in the Separation of Glycopeptides and Their Isomers. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 5001–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, C.; Liu, D.; Edmunds, G.; Wen, L.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; Wang, P.G. Solid-Phase Reductive Amination for Glycomic Analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 962, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelle, W.; Michalski, J.-C. Analysis of Protein Glycosylation by Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1585–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broberg, A. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Electrospray Ionization Ion-Trap Mass Spectrometry for Analysis of Oligosaccharides Derivatized by Reductive Amination and N, N-Dimethylation. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhaak, L.; Zauner, G.; Huhn, C.; Bruggink, C.; Deelder, A.; Wuhrer, M. Glycan Labeling Strategies and Their Use in Identification and Quantification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 3457–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemström, P.; Irgum, K. Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2006, 29(12), 1784–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, E.K.; Martin, D.; Guvench, O. Constructing 3-Dimensional Atomic-Resolution Models of Nonsulfated Glycosaminoglycans with Arbitrary Lengths Using Conformations from Molecular Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simulescu, V.; Kalina, M.; Mondek, J.; Pekar, M. Long-Term Degradation Study of Hyaluronic Acid in Aqueous Solutions Without Protection Against Microorganisms. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Gatta, A. , Salzillo, R., Catalano, C., Pirozzi, A. V. A., D’Agostino, A., Bedini, E., Cammarota, M., De Rosa, M., & Schiraldi, C. Hyaluronan-Based Hydrogels via Ether-Crosslinking: Is HA Molecular Weight an Effective Means to Tune Gel Performance? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Wang, A.; Wang, F. A Facile Crosslinked Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Strategy: Elution Conditions Adjustment. Chem. Select. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenne, L.; Gohil, S.; Nilsson, E.M.; Karlsson, A.; Ericsson, D.; Helander Kenne, A.; Nord, L.I. Modification and Cross-Linking Parameters in Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels—Definitions and Analytical Methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 91, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunmanee, S.; Jeong, Y.; Park, H. Crosslinking Method of Hyaluronic-Based Hydrogel for Biomedical Applications. J. Tissue Eng. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapuła, P.; Bialik-Wąs, K.; Malarz, K. Are Natural Compounds a Promising Alternative to Synthetic Cross-Linking Agents in the Preparation of Hydrogels? Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).