Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- SDG11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): Improper waste management has been evidenced to have direct implications, on environmental and public health [5], [6,7,8,9]. Both health dimensions cater to the optimal sustenance of humans and their immediate environs. By providing smart waste collection and processing, route optimisation, and illegal dumping detection, the aim is to ensure a cleaner, healthier and more liveable environment.

- SDG12 (Responsible Consumption and Production): Waste is a result of production and consumption of good and services, and these vary by individual need, product type, supply chain, and other demographics. The need to reduce waste generation demands a streamlined approach that robustly attacks waste generation at the source, promotes recycling and optimises resource management using applicable circular economy modelling and real-time monitoring [10,11,12].

- SDG13 (Climate Action): Research has established solid waste generation as a significant driver of climate change through greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and environmental degradation. For instance, methane (CH4) emission from open dumpsites and landfills significantly traps heat in the atmosphere, creates an offensive odour and accelerates global warming [13]. In developing economies like Nigeria, the popularly employed open-air waste incineration approach releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and particulate matter (PM). Incinerating plastic waste releases fossil-fuel-based CO2, which contributes to increasing carbon levels [14,15,16]. Additionally, [17] identifies deforestation as a source of high waste generation due to increased demand for raw materials from tree cutting, excessive mining and water resource depletion. These activities require excessive energy use in both production and disposal. Adopting data science approaches and technologies will help facilitate CH4 emission tracking through AI and satellite data, optimising waste-to-energy conversion in order to reduce carbon foot print, and providing accurate climate impact predictions.

- SDG3 (Good Health and Well-being): Waste management has been shown to correlate directly with immediate communities’ quality of life. [18] proposes the use of data analytics in predicting epidemic outbreaks as a result of poor waste management, and IoT sensors are capable of tracking air pollution following waste decomposition and incineration. Utilising data science in this regard holds two functions, minimising health hazards from improper waste disposal and improving overall public health through consistent monitoring.

- SDG6 (Clean Water and Sanitation): It may be argued that water treatment is not wholly categorised under solid waste management. Nevertheless, the removal of solid waste as pollutants in water sources makes it a critical aspect of MSW management. Moreso, as both surface and groundwater sources are critical to drinking, sanitation and aquatic life, it has become critically necessary to optimise waste treatment processes

- To analyse the application of system theory models and assessment tools in MSW management.

- To examine the current waste management landscape in Nigeria, including collection methods, disposal practices and recycling rates.

- To develop a framework for stakeholder engagement and policy integration that supports sustainable implementation of data-driven waste management approaches in the Nigerian context.

2. Systems Theory in Waste Management

3. Waste Management in Nigeria

3.1. Current Landscape

3.2. Nigeria’s MSW Management Approaches and Practices

3.2.1. Open Dumping Systems

- Open Ground Dumping: As Nigeria lacks a robust waste sorting programme, open ground dumping is quite popular because it allows the dumpsite accept all forms of heterogenous waste. However, there are no existing controls in these dumpsites such as subsurface drainage systems for the collection of leachate-waste water. Moreover, there is almost always leachate plumes during rainy seasons that if left alone flow into nearby surface water [100]. Thereby causing both land and ground water pollution.

- Dumping in Gutters: These are mostly perpetrated by market sellers, motorists, and pedestrians who feel no loyalty to the environment, as they are either passing through or staying for a short time. The operating mindset is that it is not near their home environment. Even when local government area (LGA) authorities unclog the gutters around the markets and clear blockages, it is fast filled up again with refuse and other solid waste. While one may always want to blame the government, this speaks to the poor environmental behaviour of many Nigerian citizens.

- Dumping in Water: [101,102] examine water dumping in the context of developing economies as driven by weak waste regulations, unchecked industrialisation and poor waste management infrastructure. According to [103], it poses significant environmental, social, and economic consequences given that the disposal of agricultural, industrial and domestic waste into near water bodies are neither checked nor curbed. While the environmental and public health impacts are often emphasised, the economic implications are much wider and hardly highlighted. This includes reduced tourism and economic growth especially for areas with surrounding waterbodies, rising healthcare costs and possible epidemic due to pollution related diseases, loss of fishing and dependent livelihoods.

3.2.2. Incineration Systems

3.2.3. Composting and Vermicomposting Systems

3.2.4. Controlled/Sanitary Landfills

3.2.5. Recycling System

3.3. National Legal Policy and Frameworks

3.4. Case Study Assessment

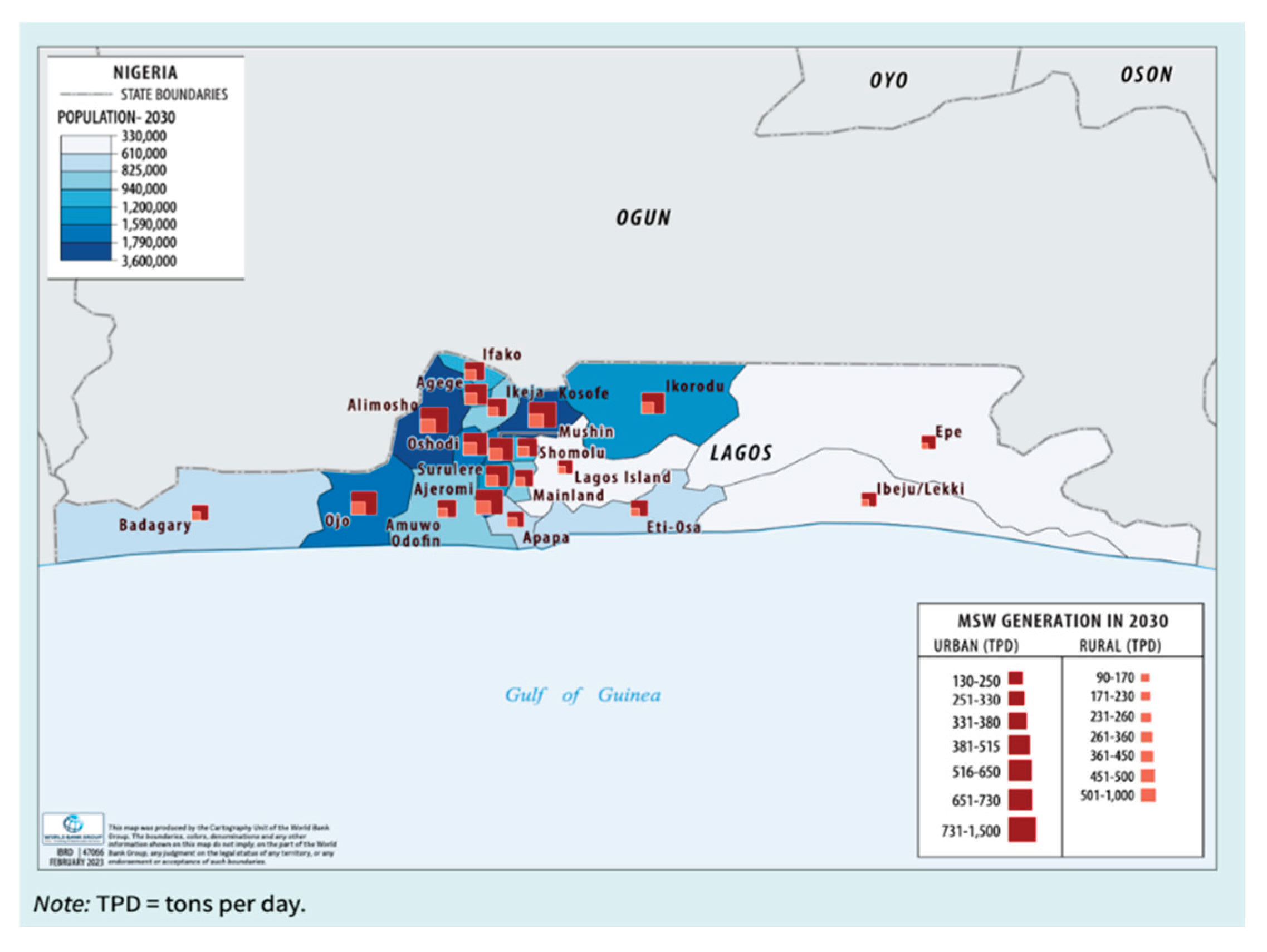

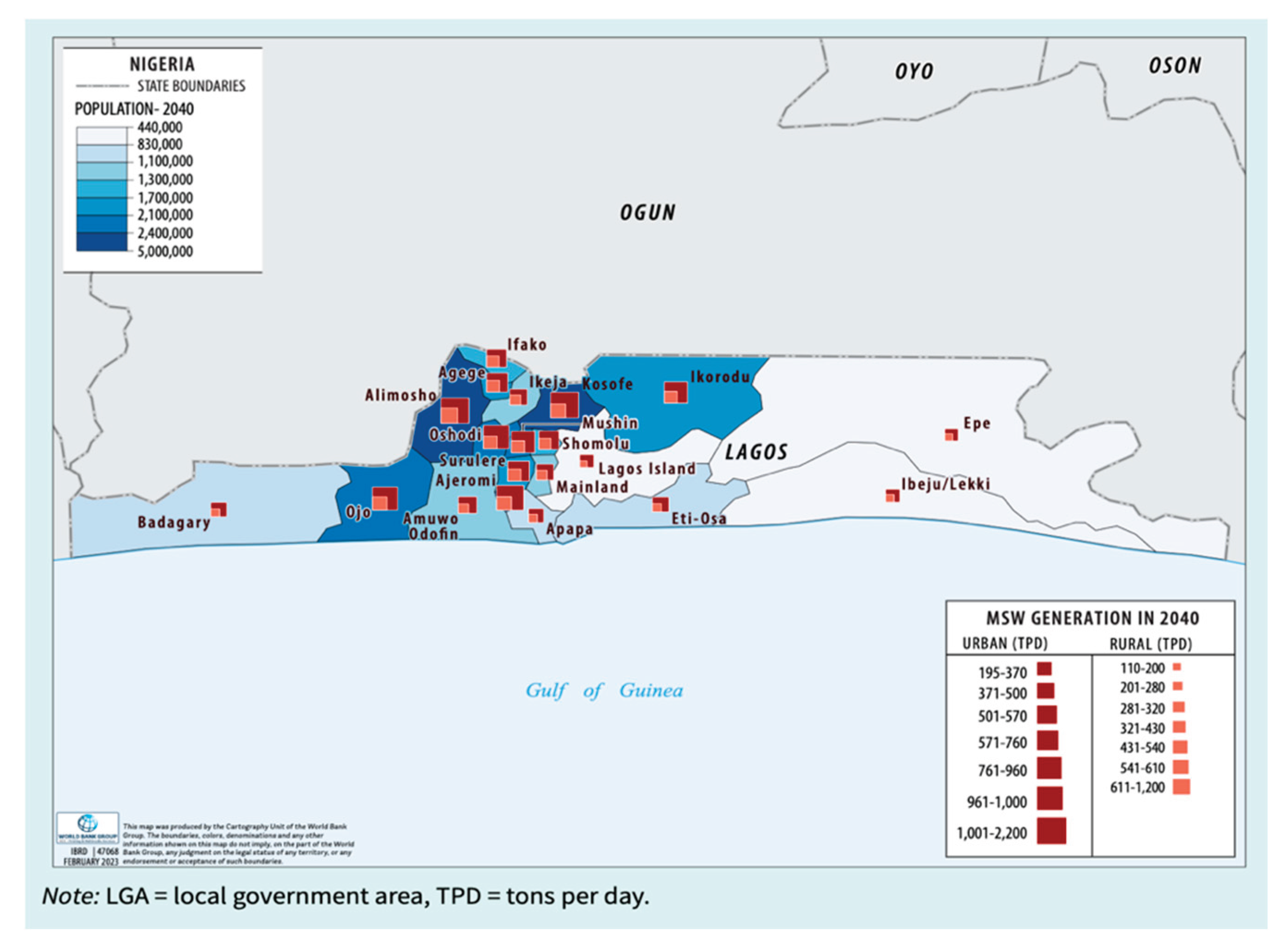

3.4.1. Lagos

3.4.2. Current State of MSW Management in Lagos

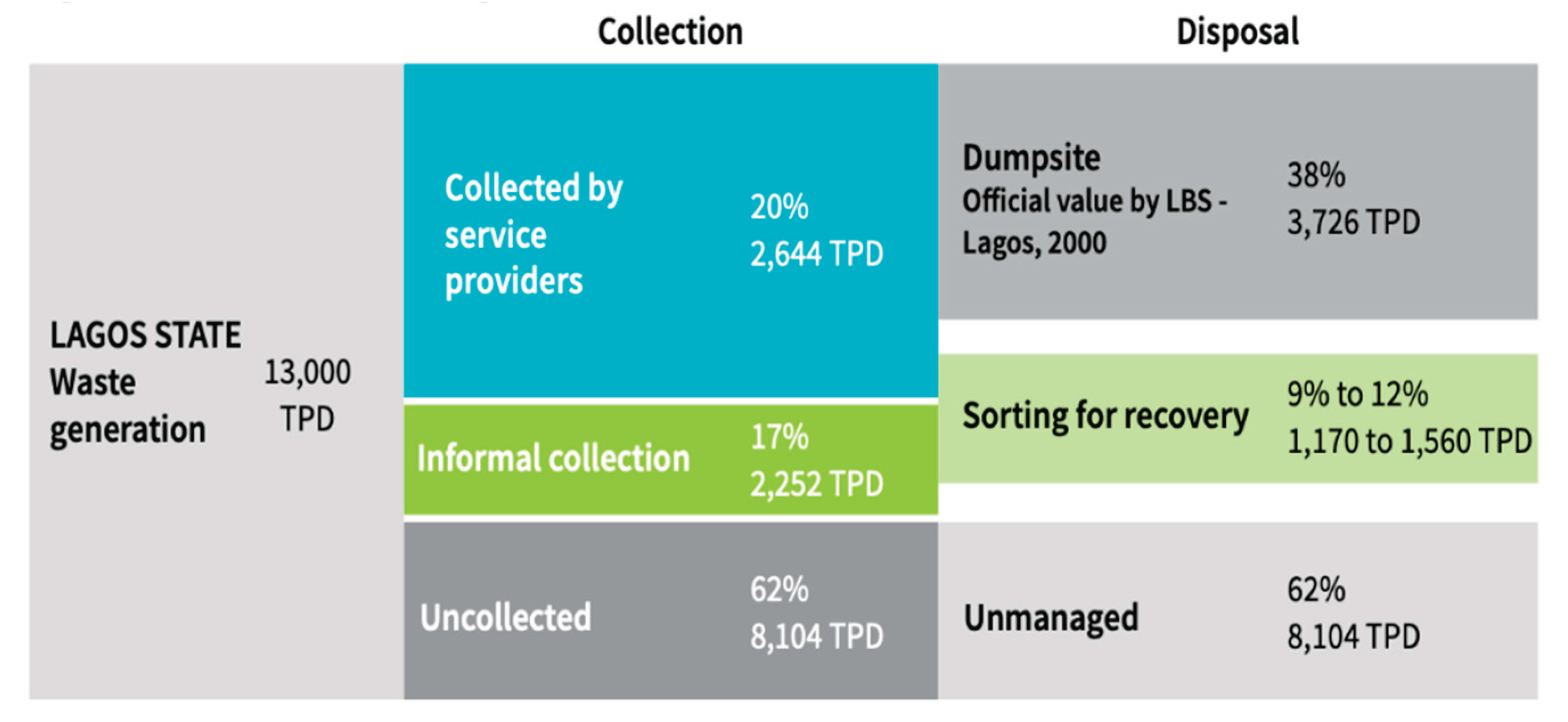

3.4.3. Collection and Disposal

3.4.4. Recycling and Resource Recovery

- Informal Sector Inefficiency: LAWMA’s view of informal scavengers is that of a nuisance as the recent policies by the State Government aims to phase out unregistered pickers. However, the transition has met resistance as these pickers are unwilling to lose their income and are reluctant in qualifying themselves to meet the State Government’s criteria to be registered [97,98]. The need for formalizing the informal sector is due to the sorting and segregation hurdles following the sector’s unsorted collection, which disrupts stability of the supply chain. Informal sector operations impede traceability and data monitoring, as they do not facilitate any accurate and consistent assessment of the amounts of data collected by scavengers and sent for recycle/recovery. Moreover, most informal operators limit their recovery operations to simple plastics such as bottles and bags, leaving more complex plastics unrecycled. Hence without formal integration, the informal sector remains an outlier limiting the states and nation’s recycling value chain efficiency.

- Limited infrastructure: Nigeria possesses very few global standard industrial recycling plants making its formal recycling infrastructure rudimentary at best. [128] report cites only Alkem Nigeria as operationally capable of treating used plastic and converting it to raw materials. The processing constraint of many acclaimed recyclers suggests an overdependence on simple re-granulators, with no ability to produce secondary raw materials. The operators simply repack scraps for sale and this limits value addition in the value chain cycle as there are few operators capable melt-index filtrating and compounding operations [99,129]. Simultaneously, waste recycling operations are further stifled by the poor intermittent electric supply which makes recycling processes significantly more expensive.

4. Proposing Data Science Utilisation in Nigeria’s Waste Management

4.1. Policy Reformation and Governance

| POLICY CHALLENGE | INTERVENTION | STRATEGY |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of stringent enforcement mechanisms | Enable independent environmental regulatory bodies with robust digital monitoring tools. |

|

| Fragmented Institutional Responsibilities | Adopt centralized segregation agency models as observed in Japan and Nordic nations like Denmark [130], Norway and Sweden [131,132]. |

|

| Poor Funding | Advancing waste management systems through inclusion of user fees, environmental levies and robust PPP frameworks. |

|

| Underdeveloped Technical and Data management Infrastructure | Real-time monitoring and data analytics. |

|

| Some Ambiguity in the Role of Stakeholders and PPP arrangements | Applying a structured stakeholder strategy |

|

| Underutilized Waste-to-Wealth and Recycling Strategies | Adopting parts of the circular economy model. |

|

| Poorly Defined Data Collection and Monitoring Frameworks | Adopt data-driven decision-making with public transparency. |

|

| Limited Focus on Awareness Campaigns | Behavioural Change Communication (BCC) and Social Marketing Techniques. |

|

| Insufficient Incentives for Research and Development (R&D) | Public-Private Research Partnerships (PPP) and Technology incubators. |

|

4.2. Stakeholder Prioritisation and Engagement

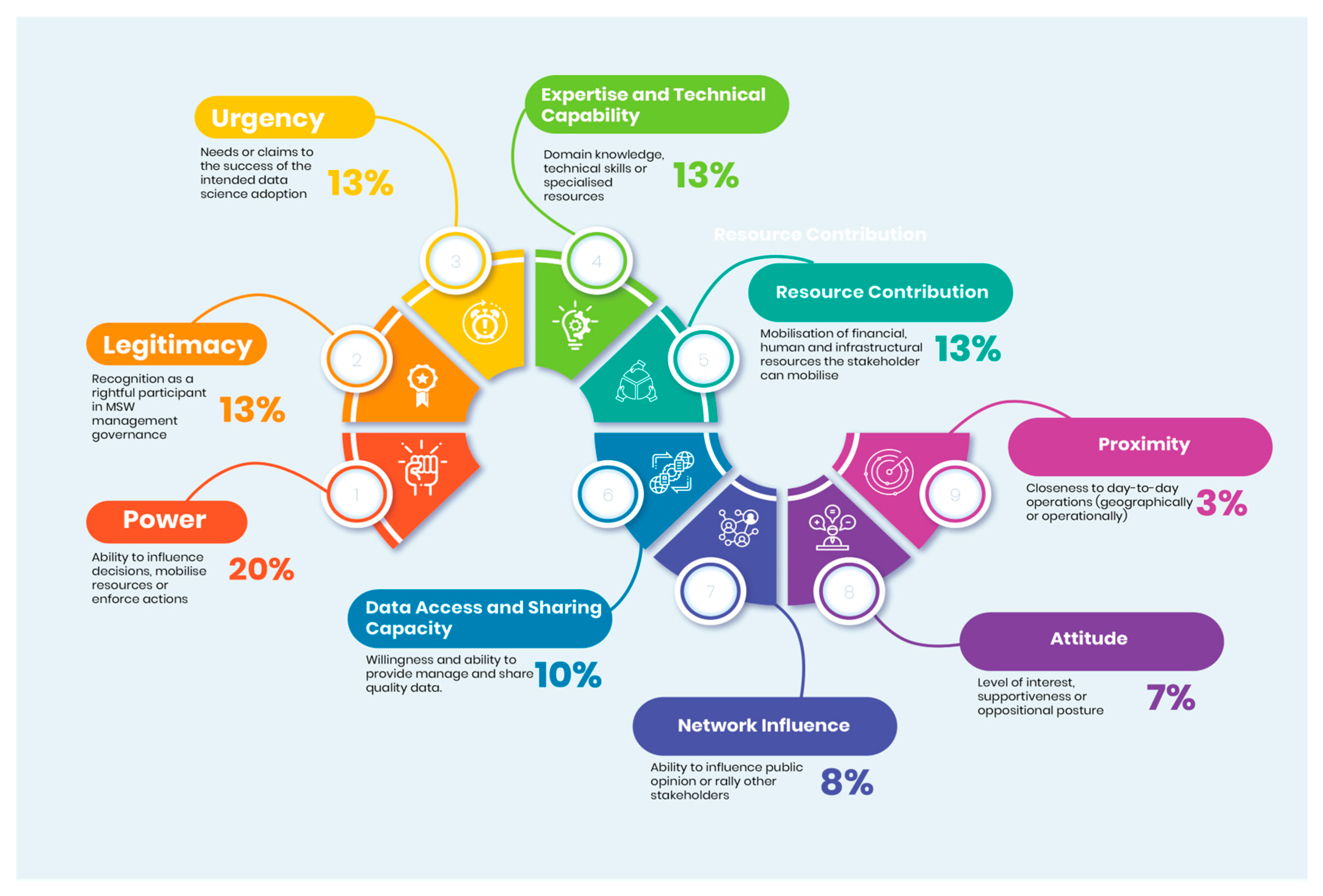

4.2.1. Staekholders Prioritisation

- PRIORITISATION CRITERIA AND WEIGHTS

-

Scoring Matrix: Adopting a scaling matrix of 0 to 5. Where:0= Non-existent; 1= Very Low; 2= Low; 3= Medium, 4= High, and 5= Very High

-

Formulae for calculating Composite Score:Composite Score= (0.20*Power) + (0.13*Legitimacy) + (0.13*Urgency) + (0.13*Expertise and Technical Capacity) + (0.13*Resource Contribution) + (0.10*Data Access and Sharing Capacity) + (0.08*Network Issue) + (0.07*Attitude) + (0.03*Proximity).

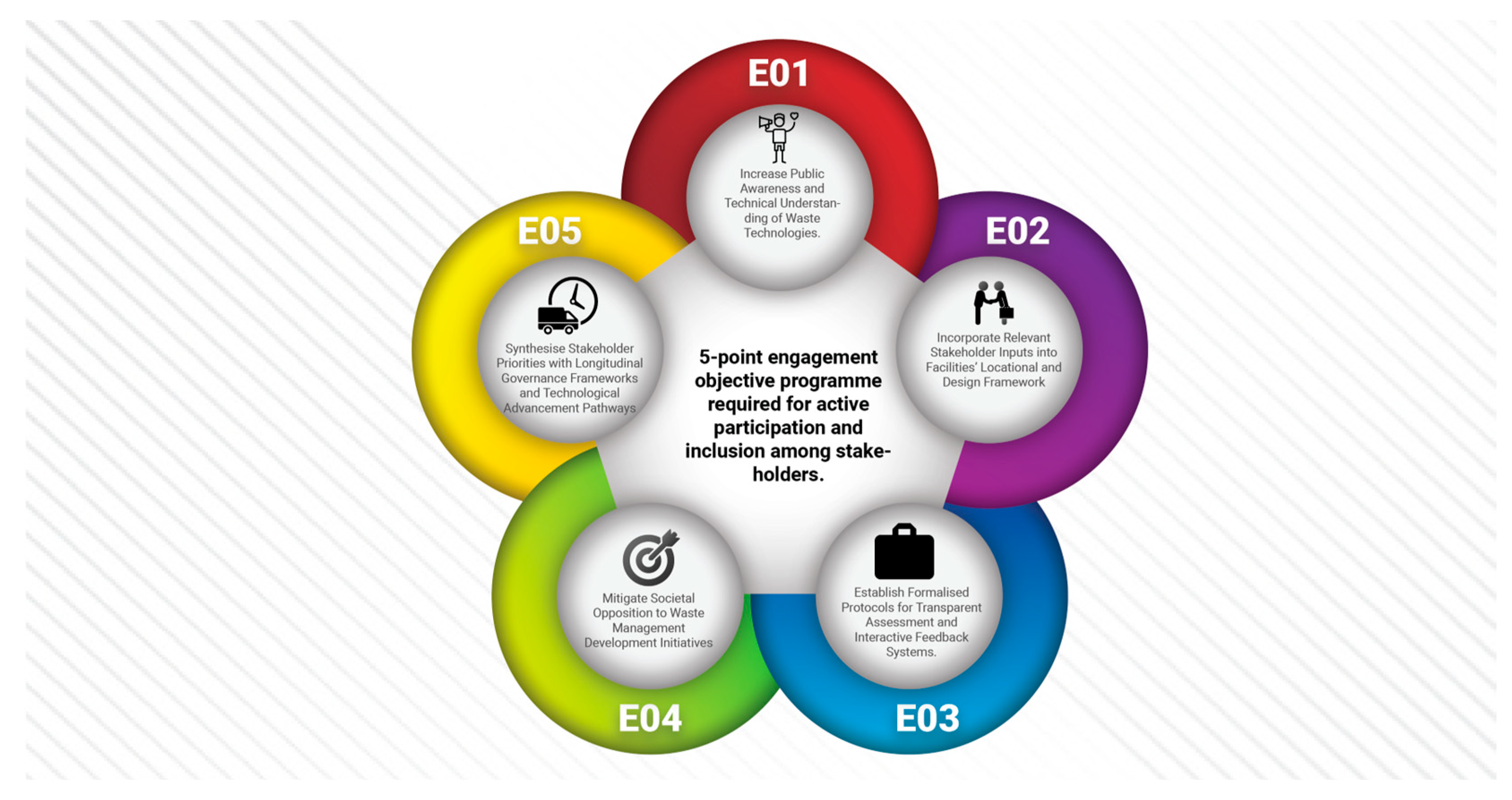

4.2.2. Stakeholder Engagement Framework

5. Recommendation for Future Studies

- Evaluating the long-term impacts of innovative technology pilots through longitudinal studies that measure how implemented technologies impact critical key performance metrics (KPIs) of Nigeria’s MSW management over the next 3 to 5 years. This will aid the identification of technology adoption barriers and maintenance challenges in the Nigerian context, also informing mitigating and scaling strategies.

- Investigating the behavior economics behind general public fee compliance. This study will identify and measure the social and psychological drivers of Nigerian household and commercial compliance to waste fee-payment. This study is highly contextual as urban, rural and peri-urban settings are bound to provide different results.

- Assessment of governance and regulatory effectiveness by examining how variations in enforcement capacity, inter-agency and inter-government level coordination influences MSW management outcomes

- Exploring the outcomes in equity and inclusion as a result of technology-driven waste management. This will require spatial analysis in assessing how IoT and data-centric systems have impacted waste management service delivery in marginalized and low-income areas.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of Competing Interests

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sondh, S.; Upadhyay, D.S.; Patel, S.; Patel, R.N. A strategic review on Municipal Solid Waste (living solid waste) management system focusing on policies, selection criteria and techniques for waste-to-value. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nlebem, B.S. Strategies for Managing Agricultural Waste to Enhance Global Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Farmers in Rivers State, Nigeria. In Proceedings of the Rivers State University Faculty of Education Conference Journal; 2022; Vol. 2; pp. 302–315. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, C.; Denney, J.; Mbonimpa, E.G.; Slagley, J.; Bhowmik, R. A review on municipal solid waste-to-energy trends in the USA. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, S.; Hickmann, T.; Lederer, M.; Marquardt, J.; Schwindenhammer, S. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development: transformative change through the sustainable development goals? Polit. Gov. 2021, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Zhang, Y.; Kumar, A.; Zavadskas, E.; Streimikiene, D. Measuring the impact of renewable energy, public health expenditure, logistics, and environmental performance on sustainable economic growth. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, S.L.; Devkota, J.P.; Amirebrahimi, J.; Smith, S.J.; Breunig, H.M.; Preble, C.V.; Satchwell, A.J.; Jin, L.; Brown, N.J.; Kirchstetter, T.W.; et al. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Human Health Trade-Offs of Organic Waste Management Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9200–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Vidal, D.G.; Dinis, M.A.P. Raising awareness on solid waste management through formal education for sustainability: A developing countries evidence review. Recycling 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Dano, U.L.; AlShihri, F.S.; AlShammari, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Al-Gehlani, W.A.G.; Alrawaf, T.I. Environmental sustainability impacts of solid waste management practices in the global South. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Effects of water pollution on human health and disease heterogeneity: a review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 880246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.B.; Vanapalli, K.R.; Samal, B.; Cheela, V.S.; Dubey, B.K.; Bhattacharya, J. Circular economy approach in solid waste management system to achieve UN-SDGs: Solutions for post-COVID recovery. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccarello, M.; Di Foggia, G. Sustainable development goals data-driven local policy: Focus on SDG 11 and SDG 12. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoji, A.A.; Ade-Omowaye, J.; Afolalu, A.; Sunday, O.A. Waste to Wealth: Engineering Solutions for SDG 12. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Science, 2024, Engineering and Business for Driving Sustainable Development Goals (SEB4SDG); IEEE; pp. 1–8.

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Ahmad, M.; Rasheed, H.; Rafique, M.I.; Ahmad, J.; Usman, A.R.A. Environmental Issues Due to Open Dumping and Landfilling. In Circular Economy in Municipal Solid Waste Landfilling. In Circular Economy in Municipal Solid Waste Landfilling: Biomining & Leachate Treatment; Pathak, P., Palani, S.G., Eds.; Radionuclides and Heavy Metals in the Environment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-07784-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Yi, S.-M.; Holsen, T.M.; Seo, Y.-S.; Choi, E. Estimation of CO2 emissions from waste incinerators: Comparison of three methods. Waste Manag. 2018, 73, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. (Micro) plastic crisis: un-ignorable contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann, P.; Daioglou, V.; Londo, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Junginger, M. Plastic futures and their CO2 emissions. Nature 2022, 612, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pona, H.T.; Xiaoli, D.; Ayantobo, O.O.; Tetteh, N.D. Environmental health situation in Nigeria: current status and future needs. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, S.M.; Mansoor, S.; Wani, O.A.; Kumar, S.S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, A.; Arya, V.M.; Kirkham, M.B.; Hou, D.; Bolan, N. Artificial intelligence and IoT driven technologies for environmental pollution monitoring and management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1336088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.-B.; Pires, A.; Martinho, G. Empowering Systems Analysis for Solid Waste Management: Challenges, Trends, and Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 1449–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarichi, L.; Techato, K.; Jutidamrongphan, W. Material flow analysis as a support tool for multi-criteria analysis in solid waste management decision-making. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.K.; Chandel, M.K. Life cycle cost analysis of municipal solid waste management scenarios for Mumbai, India. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Sharholy, M.; Alam, P.; Al-Mansour, A.I.; Ahmad, K.; Kamal, M.A.; Alam, S.; Pervez, M.N.; Naddeo, V. Evaluation of cost benefit analysis of municipal solid waste management systems. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intharathirat, R.; Abdul Salam, P. Analytical Hierarchy Process-Based Decision Making for Sustainable MSW Management Systems in Small and Medium Cities. In Sustainable Waste Management: Policies and Case Studies; Ghosh, S.K., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 9789811370700. [Google Scholar]

- Torkayesh, A.E.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Rostom, M.; Malmir, B.; Yazdani, M.; Suh, S.; Heidrich, O. Integrating life cycle assessment and multi criteria decision making for sustainable waste management: key issues and recommendations for future studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Siddiqi, A.; Narayanamurti, V. Stochastic cost-benefit analysis of urban waste-to-energy systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Mijangos, R.; De Andrés, A.; Guerrero-Garcia-Rojas, H.; Seguí-Amórtegui, L. A methodology for the technical-economic analysis of municipal solid waste systems based on social cost-benefit analysis with a valuation of externalities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 18807–18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhay, L.; Reyad, M.A.H.; Suy, R.; Islam, M.R.; Mian, M.M. Municipal solid waste generation in China: influencing factor analysis and multi-model forecasting. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamora, B.R.; de Vasconcelos Barros, R.T.; de Oliveira, L.K.; Gonçalves, S.S. Forecasting and the influence of socioeconomic factors on municipal solid waste generation: A literature review. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Horna, L.; Kahhat, R.; Vázquez-Rowe, I. Reviewing the influence of sociocultural, environmental and economic variables to forecast municipal solid waste (MSW) generation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharavy, D.; Damand, D.; Barth, M. Technological forecasting using mixed methods approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 5411–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Solid waste management through the applications of mathematical models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros Engelmann, P.; dos Santos, V.H.J.M.; da Rocha, P.R.; dos Santos, G.H.A.; Lourega, R.V.; de Lima, J.E.A.; Pires, M.J.R. Analysis of solid waste management scenarios using the WARM model: Case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 130687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pascual, J.; Fernández-González, J.M.; Ceccomarini, N.; Ordoñez, J.; Zamorano, M. The study of economic and environmental viability of the treatment of organic fraction of municipal solid waste using Monte Carlo simulation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-C.; Shang, F.; Li, P.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y. Coupling Bayesian-Monte Carlo simulations with substance flow analysis for efficient pollutant management: a case study of phosphorus flows in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahaninia, A.; Banifateme, M.; Azmayesh, M.H.; Naderi, S.; Pignatta, G. Markov and monte carlo simulation of waste-to-energy power plants considering variable fuel analysis and failure rates. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2022, 144, 062101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Akhtar, M.; Begum, R.A.; Basri, H.; Hussain, A.; Scavino, E. Capacitated vehicle-routing problem model for scheduled solid waste collection and route optimization using PSO algorithm. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulemana, A.; Donkor, E.A.; Forkuo, E.K.; Oduro-Kwarteng, S. Optimal routing of solid waste collection trucks: A review of methods. J. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4586376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefi, H.; Lim, S.; Maghrebi, M.; Shahparvari, S. Mathematical modelling and heuristic approaches to the location-routing problem of a cost-effective integrated solid waste management. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramia, M.; Pinto, D.M.; Pizzari, E.; Stecca, G. Clustering and routing in waste management: A two-stage optimisation approach. EURO J. Transp. Logist. 2023, 12, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.; Martinho, G.; Chang, N.-B. Solid waste management in European countries: A review of systems analysis techniques. J. Environ. Manage. 2011, 92, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abisourour, J.; Hachkar, M.; Mounir, B.; Farchi, A. Methodology for integrated management system improvement: combining costs deployment and value stream mapping. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3667–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Santos, G.; Gonçalves, J. Critical analysis of information about integrated management systems and environmental policy on the Portuguese firms’ website, towards sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavareshki, M.H.K.; Abbasi, M.; Karbasian, M.; Rostamkhani, R. Presenting a productive and sustainable model of integrated management system for achieving an added value in organisational processes. Int. J. Product. Qual. Manag. 2020, 30, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, Y.; Oberholster, P.; Somerset, V. A decision-support framework for industrial waste management in the iron and steel industry: A case study in Southern Africa. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 3, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, S.; Dominguez-Ramos, A.; Irabien, A. From linear to circular integrated waste management systems: A review of methodological approaches. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campitelli, A.; Kannengießer, J.; Schebek, L. Approach to assess the performance of waste management systems towards a circular economy: waste management system development stage concept (WMS-DSC). MethodsX 2022, 9, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglin, R. Economic and Environmental Assessment of a Regional Construction and Building Materials Industry in Switzerland: An Applied Combination of Material-Flow Analysis, Life-Cycle Assessment and Input-Output Analysis. PhD Thesis, ETH Zurich, 2022.

- López-Leyva, J.A.; Murillo-Aviña, G.J.; Mellink-Méndez, S.K.; Ramos-García, V.M. Energy- and water-integrated management system to promote the low-carbon manufacturing industry: an interdisciplinary Mexican case study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 10787–10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, Y.; Zhou, L. Assessing the energy efficiency potential of a closed-loop supply chain for household durable metal products in China. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 8952–8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckhof, R.; Guenther, E. Integrating life cycle assessment and material flow cost accounting to account for resource productivity and economic-environmental performance. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 1491–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Samadder, S.R. Environmental impact assessment of municipal solid waste management options using life cycle assessment: a case study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, H.; Dhar, H.; Thalla, A.K.; Kumar, S. Application of life cycle assessment in municipal solid waste management: A worldwide critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 630–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moni, S.M.; Mahmud, R.; High, K.; Carbajales-Dale, M. Life cycle assessment of emerging technologies: A review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. Life Cycle Assessment. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management; Idowu, S., Schmidpeter, R., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Del Baldo, M., Abreu, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-02006-4. [Google Scholar]

- Berticelli, R.; Pandolfo, A.; D, R.F.; Salazar, O.S.; Bohrer, R.E.G. Life cycle sustainability assessment and multi-criteria decision analysis: selection of a strategy for municipal solid waste management in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2024, 34, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, M.; Bayati, N.; Ebel, T. Life cycle sustainability assessment of waste-to-electricity plants for 2030 power generation development scenarios in western Lombok, Indonesia under multi-criteria decision-making approach. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleňáková, M.; Labant, S.; Zvijáková, L.; Weiss, E.; Čepelová, H.; Weiss, R.; Fialová, J.; Minďaš, J. Methodology for environmental assessment of proposed activity using risk analysis. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 80, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluser, B.; Plavan, O.; Teodosiu, C. Environmental impact and risk assessment. In Assessing Progress Towards Sustainability; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 189–217.

- Baloyi-Chauke, N.T. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report quality for hazardous waste treatment facilities in South Africa. PhD Thesis, North-West University (South Africa), 2023.

- Rathi, A.K.A. Integration of the standalone ‘risk assessment’section in project level environmental impact assessment reports for value addition: An Indian case analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, A. Empowering impact assessments knowledge and international research collaboration-A bibliometric analysis of Environmental Impact Assessment Review journal. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 78, 106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deus, R.M.; Mele, F.D.; Bezerra, B.S.; Battistelle, R.A.G. A municipal solid waste indicator for environmental impact: Assessment and identification of best management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Ge, Y.; Cui, C.; Xia, B.; Skitmore, M. Influences of environmental impact assessment on public acceptance of waste-to-energy incineration projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 127062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremiato, R.; Mastellone, M.L.; Tagliaferri, C.; Zaccariello, L.; Lettieri, P. Environmental impact of municipal solid waste management using Life Cycle Assessment: The effect of anaerobic digestion, materials recovery and secondary fuels production. Renew. Energy 2018, 124, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soesanto, Q.M.B.; Utomo, L.R.; Rachman, I.; Matsumoto, T. Life cycle assessment and cost benefit analysis of municipal waste management strategies. LIFE 2021, 7, 30–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Riera-Spiegelhalder, M.; Campos-Rodrigues, L.; Ensenado, E.M.; Dekker-Arlain, J. den; Papadopoulou, O.; Arampatzis, S.; Vervoort, K. Socio-economic assessment of ecosystem-based and other adaptation strategies in coastal areas: A systematic review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungsitikul, W. Evaluation of environmental impacts for non-metallic part in waste printed circuit boards (PCBs) using combined material flow analysis (MFA) and life cycle assessment (LCA). 2018.

- Birat, J.-P. MFA vs. LCA, particularly as environment management methods in industry: an opinion. Matér. Tech. 2020, 108, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maçin, K.E.; Arıkan, O.A.; Damgaard, A. An MFA–LCA framework for goal-oriented waste management studies: ‘Zero Waste to Landfill’ strategies for institutions. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2024, 0734242X241287734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyanti, A.; Rancak, G.T.; Ramadan, B.S.; Hanaseta, E. Comprehensive literature review of material flow analysis (MFA) of plastics waste: recent trends, policy, management, and methodology. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamides, E.D.; Mitropoulos, P.; Giannikos, I.; Mitropoulos, I. A multi-methodological approach to the development of a regional solid waste management system. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2009, 60, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xames, M.D.; Topcu, T.G. How Can Digital Twins Support the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability of Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review Focused on the Triple-Bottom-Line. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, E.R.; Low, J.S.; Goodship, V.; Coles, S.R.; Debattista, K. Cross-modal generative models for multi-modal plastic sorting. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henaien, A.; Elhadj, H.B.; Fourati, L.C. A sustainable smart IoT-based solid waste management system. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 157, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohankumar, A.; Gowtham, R.; Gokul, B.; Mohammed Asradh, U. Optimizing Urban Sustainability: A Smart Waste Management System with Arduino Technology. Asian J. Appl. Sci. Technol. AJAST 2024, 8, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.; Simões, C.L.; Simoes, R. Improvements to Municipal Solid Waste Collection Systems Using Real-Time Monitoring. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iratni, A.; Chang, N.-B. Advances in control technologies for wastewater treatment processes: status, challenges, and perspectives. IEEECAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 6, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Ahsan, M.; Saeed, M.H.; Mehmood, A.; El-Morsy, S. Assessment of solid waste management strategies using an efficient complex fuzzy hypersoft set algorithm based on entropy and similarity measures. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 150700–150714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, T.; Xia, H.; Cui, C. An overview of artificial intelligence application for optimal control of municipal solid waste incineration process. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, S.M. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network models for forecasting energy consumptions. Eur. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2022, 6, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, W.; Ullah, A.; Hussain, T.; Muhammad, K.; Heidari, A.A.; Del Ser, J.; Baik, S.W.; De Albuquerque, V.H.C. Artificial Intelligence of Things-assisted two-stream neural network for anomaly detection in surveillance Big Video Data. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 129, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Mohanty, S.K.; Mohapatra, A.G. Real-Time Monitoring and Fault Detection in AI-Enhanced Wastewater Treatment Systems. In The AI Cleanse: Transforming Wastewater Treatment Through Artificial Intelligence; Garg, M.C., Ed.; Springer Water; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-67236-1. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, P.; Salomé Duarte, M.; Novais, P. Conception and evaluation of anomaly detection models for monitoring analytical parameters in wastewater treatment plants. AI Commun. 2024, 37, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasting, M.S. Industry 4.0 in Waste Management. Master’s Thesis, NTNU, 2019.

- Gulyamov, S. Intelligent waste management using IoT, blockchain technology and data analytics. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2024; Vol. 501; p. 01010. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, M. Reducing waste in warehouse operations through EWM system optimization: A case study of SAP-enabled solutions. Master’s Thesis, Πανεπıotaστ\acute\etaμıotao Πεıotaραıota\acuteømegaς, 2024.

- Shah, P.J.; Anagnostopoulos, T.; Zaslavsky, A.; Behdad, S. A stochastic optimization framework for planning of waste collection and value recovery operations in smart and sustainable cities. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambella, C.; Maggioni, F.; Vigo, D. A stochastic programming model for a tactical solid waste management problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sinwar, D.; Saini, M.; Saini, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, M.; Singh, D.; Lee, H.-N. Efficient computational stochastic framework for performance optimization of E-waste management plant. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4712–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.O.; Ayejoto, D.A.; Fahad, A.; Mohammed, M.A.A.; Saqr, A.M.; Joy, A.O. Environmental Burden of Waste Generation and Management in Nigeria. In Technical Landfills and Waste Management; Souabi, S., Anouzla, A., Eds.; Springer Water; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-55664-7. [Google Scholar]

- Alao, J.O.; Fahad, A.; Danladi, E.; Danjuma, T.T.; Mary, E.T.; Diya’ulhaq, A. Geophysical and hydrochemical assessment of the risk posed by open dumpsite at Kaduna Central Market, Nigeria. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeudu, O.B.; Agunwamba, J.C.; Ugochukwu, U.C.; Ezeudu, T.S. Temporal assessment of municipal solid waste management in Nigeria: prospects for circular economy adoption. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 36, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezirim, I.; Agbo, F. Role of National Policy in Improving Health Care Waste Management in Nigeria. J. Health Pollut. 2018, 8, 180913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, C.C.; Ezeibe, C.C.; Anijiofor, S.C.; Daud, N.N. Solid waste management in Nigeria: problems, prospects, and policies. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2018, 44, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeadibe, T.C.; Ejike-Alieji, A.U.P. Solid waste management during Covid-19 pandemic: policy gaps and prospects for inclusive waste governance in Nigeria. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, C.C. Status of municipal solid waste generation and disposal in Nigeria. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2015, 26, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntoyinbo, O.O. Informal waste management system in Nigeria and barriers to an inclusive modern waste management system: A review. Public Health 2012, 126, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbonna, A.C.; Mikailu, A. The role of the informal sector in sustainable municipal solid waste management: A case study of Lagos State, Nigeria. Ann. Fac. Eng. Hunedoara 2019, 17, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ogwueleka, T.C.; Naveen, B.P. Activities of informal recycling sector in North-Central, Nigeria. Energy Nexus 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.O. Impacts of open dumpsite leachates on soil and groundwater quality. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 20, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breukelman, H.; Krikke, H.; Löhr, A. Failing services on urban waste management in developing countries: A review on symptoms, diagnoses, and interventions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozoh, A.N.; Longe, B.T.; Akpe, V.; Cock, I.E. Indiscriminate solid waste disposal and problems with water-polluted urban cities in Africa. J. Coast. Zone Manag. 2021, 24, 1000005. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, S.H.A.; Van Leeuwen, C.J. The challenges of water, waste and climate change in cities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 385–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Berruti, F. Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1433–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, Y.; Yakubu, R.O.; Abdulazeez, A.A.; Ijeoma, M.W. Exploring Nigeria’s waste-to-energy potential: a sustainable solution for electricity generation. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.; Prakash, D.; Gupta, S.; Nazareno, M.A. Role of Vermicomposting in Agricultural Waste Management. In Sustainable Green Technologies for Environmental Management. In Sustainable Green Technologies for Environmental Management; Shah, S., Venkatramanan, V., Prasad, R., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 9789811327711. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiao, R.; Klammsteiner, T.; Kong, X.; Yan, B.; Mihai, F.-C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. Recent trends and advances in composting and vermicomposting technologies: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehrei, F.; Ameen, F. Vermicomposting: A management tool to mitigate solid waste. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3284–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste management through composting: Challenges and potentials. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravanian, A.; Ravari, S.O. Types of contamination in landfills and effects on the environment: A review study. In Proceedings of the IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science; IOP Publishing, 2020; Vol. 614; p. 012083. [Google Scholar]

- Mor, S.; Ravindra, K. Municipal solid waste landfills in lower-and middle-income countries: Environmental impacts, challenges and sustainable management practices. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, L.; Popoola, L.T. A Comprehensive Review of Atmospheric Air Pollutants Assessment Around Landfill Sites. Air Soil Water Res. 2023, 16, 11786221221145379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasen, T.B.; Scheutz, C.; Kjeldsen, P. Treatment of landfill gas with low methane content by biocover systems. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetri, J.K.; Reddy, K.R. Advancements in Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Cover System: A Review. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2021, 101, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, M.A.; Norashiddin, F.A.; Yusoff, M.S.; Hanif, M.H.M.; Wang, L.K.; Wang, M.-H.S. Sanitary Landfill Operation and Management. In Solid Waste Engineering and Management. In Solid Waste Engineering and Management; Wang, L.K., Wang, M.-H.S., Hung, Y.-T., Eds.; Handbook of Environmental Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-84178-2. [Google Scholar]

- Imam, A.; Mohammed, B.; Wilson, D.C.; Cheeseman, C.R. Solid waste management in Abuja, Nigeria. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2: Ministry of Environment National Policy on Solid Waste Management, 2020.

- Johnson, A. How Africa’s largest city is staying afloat 2021.

- A: Lagos State Development Plan 2052, 2052.

- Chidi, O.C.; Badejo, A.E. EMERGING ISSUES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF LAGOS AS A MEGA-CITY. UDS Int. J. Dev. 2024, 11, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Dawodu, A.; Oladejo, J.; Tsiga, Z.; Kanengoni, T.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Underutilization of waste as a resource: bottom-up approach to waste management and its energy implications in Lagos, Nigeria. Intell. Build. Int. 2022, 14, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auwalu, F.K.; Bello, M. Exploring the contemporary challenges of urbanization and the role of sustainable urban development: a study of Lagos City, Nigeria. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2023, 7, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K.T.; Ajai, O. Municipal solid waste management in Lagos State: Expansion diffusion of awareness. Waste Manag. 2024, 190, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S.U. Effects of Private Waste Collectors’ Capacity, Experience and Trip-count on Revenue in Lagos State. J. Arid Zone Econ. 2024, 3, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, M.J.D. Solid Waste Management Laws and Methods of Disposal in Nigeria: A Case Study of Lagos, Akwa Ibom and Cross River States. J. Emerg. Trends Econ. Manag. Sci. 2023, 14, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, K. ASWOL website launched toverify genuine waste pickers. Guard. Niger. News - Niger. World News.

- Ezeudu, O.B.; Oraelosi, T.C.; Agunwamba, J.C.; Ugochukwu, U.C. Co-production in solid waste management: analyses of emerging cases and implications for circular economy in Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 52392–52404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020.

- Akanle, O.; Shittu, O. Value chain actors and recycled polymer products in Lagos metropolis: Toward ensuring sustainable development in Africa’s megacity. Resources 2018, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.A.C.; Ishida, A. An overview of residential food waste recycling initiatives in Japan. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhi, A.; Rosenlund, J. Municipal solid waste management in Scandinavia and key factors for improved waste segregation: A review. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 8, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Кoваленкo, Є.В.; Рoсoхата, А.С.; Артюхoв, А.Є.; Нєшева, А.Д.; Казимірoва, В.О.; Гавриленкo, О.М. Development of Waste Management Systems in the Context of Energy Policy and Their Impact on Ecology and Sustainability: The Experience of the Scandinavian Countries. Екoнoмічний Прoстір.

- Gopalakrishnan, P.K.; Hall, J.; Behdad, S. Cost analysis and optimization of Blockchain-based solid waste management traceability system. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Dutra, R.M.; Siman, R.R. Strategies for financial sustainability of municipal solid waste management systems. Rev. Gestao Soc. E Ambient. 2024, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, M.A.; Obo, U.B.; Ugwu, U. Managing sustainable development in our modern cities: Issues and challenges of implementing Calabar urban renewal programmes, 1999-2011. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SYSTEM ENGINEERING MODEL | ATTRIBUTES [19] | APPLICATION IN MSW MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) |

|

|

| Forecasting Models (FM) |

|

|

| Simulation Models (SM) |

|

|

| Optimisation Models (OM) |

|

|

| Integrated Modelling Systems (IMS) |

|

|

| SYSTEMS ASSESSMENT TOOLS | CHARACTERISTICS [19] and [40] | APPLICATION IN MSW MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario Development (SD) |

|

|

| Material Flow Analysis (MFA) |

|

|

| Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) |

|

|

| Risk Assessment (RA) |

|

|

| Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) |

|

|

| Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) |

|

|

| Socioeconomic Assessment (SoEA) |

|

|

| Sustainable Assessment (SA) |

|

|

| SYSTEMS THEORY PRINCIPLE | [71] view | DATA SCIENCE APPLICATION TO WASTE MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Holistic Perspective |

|

|

| Interconnectivity and Feedback Loops |

|

|

| Dynamic and Adaptive Nature |

|

|

| Input-Throughput-Output Model |

|

| Stakeholder | Power | Legitimacy | Urgency | Attitude | Proximity | Expertise and Technical Capability | Resource Contribution | Network Influence | Data Access and Sharing Capacity | Composite Score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Waste Management Authorities | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4.74 | 1st |

| State Ministry on Environment | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4.58 | 2nd |

| Private waste companies | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4.35 | 3rd |

| Waste Technology Providers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3.91 | 4th |

| Federal Ministry of Environment | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3.66 | 5th |

| Local Government Area (LGA) councils | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3.41 | 6th |

| NGOs | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3.41 | 6th |

| NESREA | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3.10 | 8th |

| Academic Institutions | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.08 | 9th |

| CBOs | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3.05 | 10th |

| Financial Institutions | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1.80 | 11th |

| General Public | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.54 | 12th |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).