1. Introduction

Maintaining independence in the home is important as the US population continues to age and fall-related medical spending continues to increase [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Nearly half of older adults are unable to get up from the floor after a fall in the absence of injury, and floor transfer (FT) ability is associated with falls, physical function, hospitalization, need for caregiver support, and even mortality [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] . Getting up from the floor, a task that becomes more difficult with age, is considered a geriatric functional milestone to routinely screen and use to identify functional impairments [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].Unfortunately, the limited research available suggests clinicians infrequently assess the ability of their older patients to perform a floor transfer [

16,

17].

Since FT ability is associated with health status in older adults, FT assessment and training is a vital component of patient care [

5,

6]. Self-report measures may assist clinicians with decision-making for safely and effectively integrating the FT into clinical practice [

6,

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Previous research has shown that a patient’s self-reported FT ability level (i.e., independent, assisted, or dependent) is associated with actual ability, and thus clinicians can use this information as a screening tool [

6]. Clinicians may also consider utilizing the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I), common in clinical practice, since some research has shown older adults who experienced difficulty getting up from the floor report greater fear of falling (FoF) [

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Additional use of self-report measures that assess other life-domains using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), such as physical function and self-efficacy, could provide a multidimensional picture of a patient’s perspective of abilities that may relate to FT ability [

25]. The measure of self-efficacy (SE) in managing daily activities, which is confidence in the ability to perform daily activities without assistance, has been shown to independently predict health outcomes [

26,

27]. Physical function (PF), which assesses self-perceived physical ability, has been validated across diverse patient populations and implicated in fall risk [

28,

29]. Little is known, however, about the extent to which the FES-I and PROMIS SE and PF self-report measures are associated with how quickly and in what way older adults get up from the floor. Since fear of falling and patient self-assessment of SE and PF may be associated with FT ability, understanding these relationships could assist therapists in providing tailored FT assessment and treatment strategies.

In addition to subjective measures such as self-reported FT ability level, the time to complete the five-time sit-to-stand test (5XSTS) is an objective measure clinicians can use as a screening tool since it has moderate sensitivity and strong specificity in predicting FT ability level in older adults [

13]. Thus, 5XSTS time is useful for directing clinical decisions related to FT assessment and interventions [

6,

13,

30,

31,

32]. Except for time to perform the task, however, performance factors related to the 5XSTS have not been evaluated in their relation to FT ability. The extent to which lower extremity joint torques and powers during the 5XSTS task are associated with FT time and differ in people who get up from the floor utilizing different strategies, is unknown [

6]. Such information would be clinically useful by providing insights into the role of the lower extremity joints in FT ability, assisting clinicians in prescribing exercises that optimally target individual impairments.

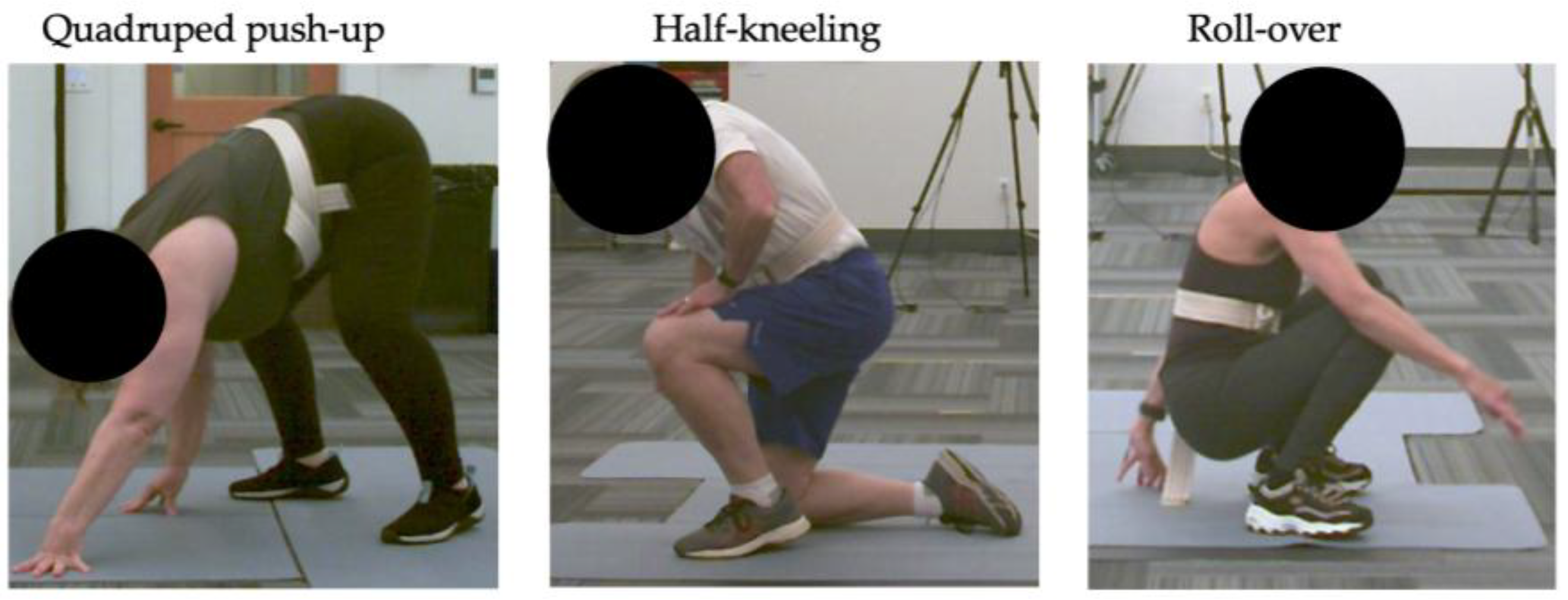

When older adults get up from the floor, three commonly performed strategies have been observed: getting up from a half-kneeling position, pushing up from a quadruped position to standing, and rolling forward and up to standing [

14]. Despite the variety of strategies used by older adults, therapists most commonly teach the half-kneeling strategy [

5,

6,

33,

34,

35]. Instructing a single strategy, rather than one in which the patient is most comfortable or able to perform, may limit the translation to real-world FT performance. Given the variability of FT performance, information that would assist therapists in anticipating a patient’s self-selected strategy could optimize the ability of clinicians to facilitate patient success and safety during FT assessment and training. Self-report measures (i.e., FES-I, SE, and PF) may differ in individuals who choose different FT strategies and common strategies may involve differing biomechanical demands that could be clinically useful to integrate into patient care. Additional information on differences in lower extremity joint torques and powers between the commonly instructed half-kneeling FT strategy and a sit-to-stand activity (i.e., 5XSTS test) could assist clinicians in exercise prescription decisions to enhance FT ability.

This study had multiple aims. One aim determined the associations between FT time and age, 5XSTS time, scores on self-report measures, and lower extremity joint torques and powers during the 5XSTS. Longer FT times were hypothesized to be associated with advanced age, longer 5XSTS time, higher FES-I scores, lower SE and PF scores, and decreased lower extremity joint torques and powers during the 5XSTS task. A second aim determined differences in self-report measures, FT time, 5XSTS time, biomechanical factors related to the 5XSTS, and peak lower extremity joint angles during the FT in older adults who performed different FT strategies. It was hypothesized that differences would be found when comparing strategies. Lastly, this study determined the extent to which lower extremity joint angles, torques and powers differed during the 5XSTS and a commonly instructed FT strategy. Biomechanical demands were hypothesized to be greater in the instructed FT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection and Consent

A convenience sample of participants were recruited from November 2023 through May 2024 in the surrounding area through fliers and word of mouth. To participate, individuals needed to be 50-80 years old, living independently in the community or an assisted living facility, able to walk at least 15 feet, speak English, and self-report willingness to attempt to get up from a chair and the floor. Participants were excluded if the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS) indicated dementia, with a cut off score of 21 or lower for those with at least a high school education or a score of 20 or lower for those with less than a high school education [

36]. Patients were also excluded if they self-reported a neurologic condition, unstable angina, or joint replacement or major surgery in the previous six months. Further exclusion criteria included experiencing a concussion in the last 3 months, dizziness in the past 2 weeks, current severe pain rated 7/10 or greater, or any condition that would prevent participants from getting up and down from the floor safely. Furthermore, resting vital signs needed to be within limits deemed safe for physical activity [

37,

38].

An a priori analysis was conducted (G*Power, Version 3.1.9.6, Kiel, Germany) to determine the sample size needed for this study. Using a one-way ANOVA with fixed effects to determine an effect size of 0.4 at an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, 30 participants were found necessary to determine differences between the three commonly performed FT strategies used by older adults.

2.2. Study Procedures

2.2.1. Self-Report Measures

Participants filled out self-report questionnaires that included the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I), the Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA), and Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures of self-efficacy during daily activities (SE) and physical function (PF). The FES-I was chosen because it is commonly used clinically to measure FoF in older adults and FoF is associated with difficulty getting up from the floor after a fall [

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The FES-I is a valid and reliable measure with 16 questions scored on a 4-point scale from 1 (not at all concerned) to 4 (very concerned) that total to indicate low (16-19), moderate (20-27), and high (28-64) levels of concern for falling [

18,

19,

20,

21,

23]. The RAPA, a valid and reliable measure of physical activity levels in older adults, was completed to characterize participant activity levels [

39,

40]. Items from the RAPA 1 section of the questionnaire measure aerobic activity and RAPA 2 items measure strength and flexibility activity [

39,

40]. The PROMIS measures of SE and PF were chosen to utilize patient-centered measures that provide information related to patient perception of abilities [

41,

42,

43]. These PROMIS measures are computer adaptive tests (CAT), which rely on an item-bank to measure a construct (e.g., physical function) through an individually tailored questionnaire that produces a T-score [

42,

43]. A T-score of 50 equates to the mean of the general U.S. population for most domains, except for SE which is normed to a clinical population with chronic conditions [

41,

42]. The measure of PROMIS SE assesses confidence in one’s ability to perform various daily activities without assistance [

42]. The measure of PROMIS PF assesses self-reported physical capability, which includes dexterity, mobility and walking, and instrumental activities of daily living [

43]. Both measures of PROMIS SE and PF have been validated across diverse patient populations [

26,

28,

44,

45,

46].

2.2.2. Study Activities

Participant height and weight were measured and recorded. Participants wore a gait belt and performed the 5XSTS with a 5-min break before completing a FT task in a self-selected manner (self-selected FT). If participants performed the self-selected FT task independently, they additionally performed a FT task in a commonly instructed manner (instructed FT). Participants verbally reported their rate of perceived exertion (RPE) after the 5XSTS and self-selected FT tasks. All study movements were recorded with a markerless motion capture system (Theia3D, Kingston, Ontario, Canada) with 11 cameras (Qualysis, Goteborg, Sweden) at 120 Hz. Two force plates (AMTi, Watertown, Massachusetts, USA) recording at 1200 Hz captured kinetic data during the 5XSTS and instructed FT tasks.

2.2.3. 5XSTS Task

Participants performed a 5XSTS, previously shown to predict FT ability level, as fast as possible from a standard height chair (18”) with arms crossed over their chest while guarded by a researcher [

13]. Time was recorded from the researcher’s verbal command “go” until the participant touched the chair after the 5th repetition [

30].

2.2.4. Self-Selected FT Task

Since older adults get up from the floor in a variety of ways and FT ability is associated with health status, participants were asked to perform a timed FT using a self-selected FT strategy [

5,

6,

14,

33,

34,

35]. Participants were instructed to lie on the floor in supine. On the researcher’s verbal command “go”, participants stood up as fast as possible to their full height in any way they chose with a researcher standing nearby [

5,

14]. Time was recorded from the researcher’s verbal start until the participant achieved their full balanced standing height. A second researcher characterized the transfer by level of independence (i.e., independent, assisted, or dependent) and strategy used. The FT strategy was identified based on the participant position observed while transitioning to standing regardless of movement patterns utilized to transition from supine. Strategies were characterized as half-kneeling (half-kneel), roll-over, or quadruped push-up (quadruped), per published definitions [

5,

14] (

Figure 1). The primary investigator characterized strategies initially and consulted a second researcher when transfer strategies were not immediately apparent.

2.2.5. Instructed FT Task

Participants watched a video demonstrating and describing a standardized FT using the half-kneeling strategy commonly performed by older adults and instructed by clinicians during FT training [

5,

6,

33]. Participants were verbally cued to ensure lead foot positioning on a force plate to record forces through the limb and instructed to not use their hands when moving from the half-kneeling position to standing. Isolating the lead limb on a single force plate and removing upper extremity assistance was necessary to quantify lower extremity demand through biomechanical analyses. Participants repeated this task until three trials were successfully recorded as instructed, 5 total trials were performed, or the participant ended their participation. Rest between trials was given as needed.

2.3. Data Analysis

A biomechanical model of the lower and upper extremities, pelvis and trunk were created with Theia3D to calculate lower extremity joint angles, moments and powers during the study tasks. During the 5XSTS and self-selected FT tasks, peak dorsiflexion, knee flexion and hip flexion angles were identified from either limb. Peak joint angles were also identified from the lead limb during the instructed FT Task. Peak internal joint torques and power, normalized to body mass, for ankle plantar flexion, knee extension and hip extension were also identified from either limb during the 5XSTS and the lead limb during instructed FT task. Peak values of biomechanical variables were averaged across the three successful trials of the instructed FT task. Biomechanical data was not available for two participants for the 5XSTS task due to technical difficulties, with one of these participants also missing biomechanical data from the instructed FT due to inability to perform the task without upper extremity support. Biomechanical data on the instructed FT was not available from eight additional participants due to factors occurring in isolation or combination that included inability to perform all trials without upper extremity assistance, foot placement that was not isolated on a force plate and voluntarily ending the study session before completion of all activities. Thus, biomechanical data from these participants were not included in the relevant statistical analyses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normality testing was performed on scores from self-report measures and biomechanical variables during the study tasks using skewness and kurtosis values, with >3 indicating a violation of normality assumptions. Some biomechanical variables related to the 5XSTS and instructed FT task kinetics violated normality assumptions and required nonparametric testing for analyses. To determine any association between FT time and age, as well as 5XSTS time and scores on self-report measures, Pearson correlations were performed. Spearman correlations were performed to identify any association between FT time and 5XSTS lower extremity joint torques and powers. To determine differences in older adults who chose the various FT strategies, self-report measure scores, 5XSTS time, FT time, and peak lower extremity joint angles during the self-selected FT were each compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the omnibus ANOVA was significant (p < 0.05), independent t-tests were performed between pairs of the three FT strategies. To determine differences in lower extremity joint torques and powers during the 5XSTS task between pairs of FT strategies, Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed. When the omnibus Kruskal-Wallis tests were significant (p < 0.05), post-hoc Dunn’s testing was performed. Lastly, to compare lower extremity demands between the 5XSTS and instructed FT tasks, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks tests determined differences in lower extremity peak joint angles, moments and powers. Statistical tests were Bonferroni corrected to account for the multiple tests performed. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS (Version 27; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Study Activity Performance

Thirty-five community-dwelling older adults provided informed consent to participate in study activities, of which 34 (13 men and 21 women) with a mean age of 69 (SD = 9) years met the study’s eligibility criteria. Participants self-reported their race/ethnicity as 91.2% White, 5.9% Hispanic, and 2.9% Asian. Participant characteristics are reported in

Table 1. Mean scores on the FES-I indicated a low level of FoF on average, with 79% and 21% of participants categorized as having low (score of 16-19 out of 64) and moderate (score of 20-27 out of 64) concern for falling, respectively [

18,

19,

20,

21,

23]. Mean RAPA 1 scores were 6.2 (SD = 0.8), with 85% of participants categorized as “active,” indicated by a score of 6-7 out of 7 points [

39,

40]. Mean RAPA 2 scores out of a possible 3 points were 2.2 (SD = 1.1) with 88% of participants performing strength and/or flexibility exercises weekly, indicated by a score of at least 2 points. Mean (SD) PROMIS scores, referenced to a mean 50-point T-score, were 54.2 (4.9) for SE and 53.7 (6.5) for PF, indicating slightly higher scores than the reference population average [

41]. Mean (SD) 5XSTS and FT times were 9.6 (1.7) and 4.7 (2.1) seconds, respectively (Table 2). All participants performed the self-selected FT task independently, with 17 (50%), 11 (32.4%), and 6 (17.6%) using the half-kneel, quadruped, and roll-over strategies, respectively.

3.2. FT Time Correlations

As depicted in

Table 2, longer FT times were significantly and moderately associated with greater age (r = 0.52, p = 0.002) and longer 5XSTS times (r = 0.56, p < 0.001). Shorter FT times strongly trended toward a significance with a moderate association with greater 5XSTS peak knee power (r = -0.46, p = 0.009). No associations were found between FT time and the self-report measures used in this study.

3.3. Differences Between Participants Who Performed Various FT Strategies

3.3.1. Self-Report Measures

No significant differences were found in self-report measures between the different self-selected FT strategies (

Table 3), though there was a trend toward significant differences in FES-I scores between individuals who performed the quadruped and half-kneeling strategies. Mean FES-I scores were higher by 1.9 points in those using the quadruped (19.4) than the half-kneel strategy (17.5) (p = 0.028), indicating a slightly greater FoF for the former, though individuals who used both strategies reported a low level of concern for falling.

3.3.2. FT Time and 5XSTS Performance

No significant differences were found in FT time, 5XSTS time, or lower extremity joint moments and powers during the 5XSTS task between participants who used different self-selected FT strategies. There was a trend toward significant differences in FT time between some pairs of self-selected strategies. The quadruped strategy took on average, 2.2 and 2.6 s longer to perform than the half-kneel strategy (p = 0.013) and roll-over strategy (p = 0.030), respectively.

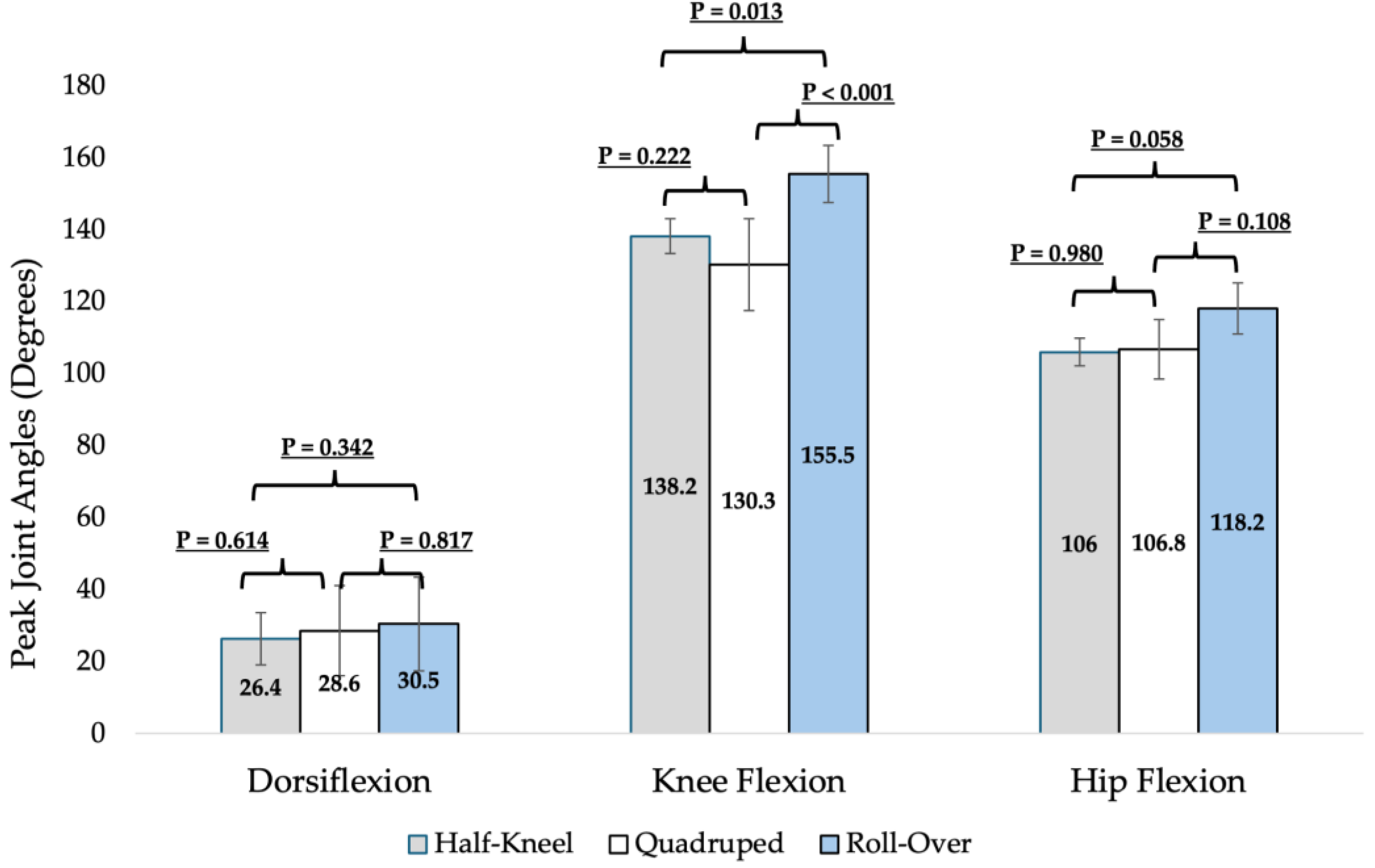

3.3.3. Joint Angles During Self-Selected FT

Significant differences in peak joint angles of the lower extremities were found during performance of the self-selected FT strategies (

Figure 2). Peak knee flexion angles during the roll-over strategy were significantly greater than the quadruped strategy by an average of 25.2 degrees (p < 0.001). There was a strong trend toward significance with greater peak knee flexion during the roll-over strategy than the half-kneel strategy by 17.3 degrees (p = 0.013).

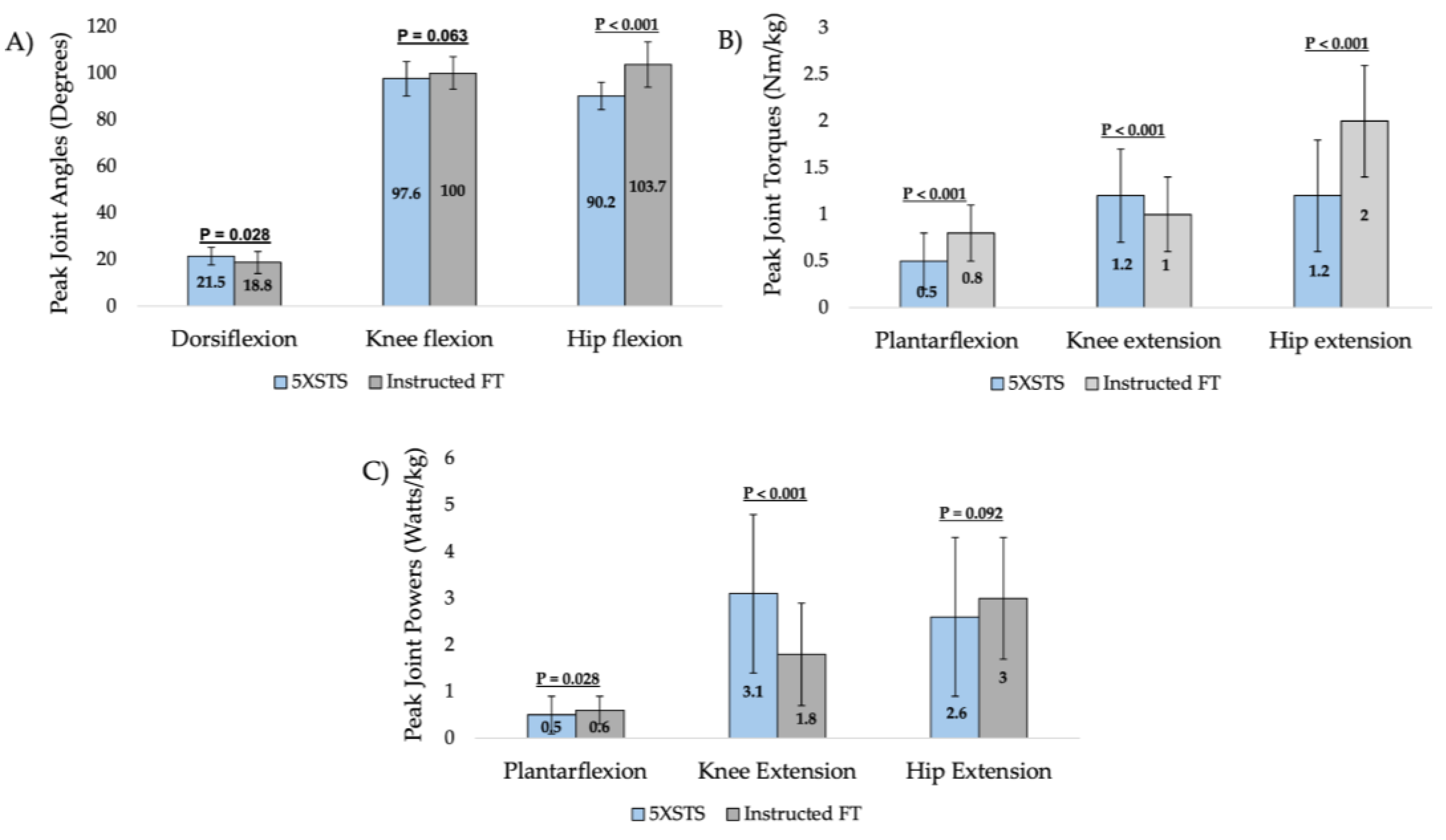

3.4. Lower Extremity Demands Between 5XSTS and Instructed FT

Significant differences were found in lower extremity peak joint angles, torque and powers between the 5XSTS and instructed FT tasks in the 24 participants with biomechanical data available for both tasks (

Figure 3). Peak hip flexion was significantly greater in the instructed FT task than the 5XSTS task (p < 0.001). Peak ankle plantar flexion torque (p < 0.001), peak knee extension torque and power (p < 0.001), and peak hip extension torque (p < 0.001) also differed significantly between the tasks. Ankle and hip demands were generally greater in the instructed FT while knee demands were generally greater in the 5XSTS task.

4. Discussion

Getting up from the floor is a key functional movement for independence in older adults, and an important component of screening for declining mobility [

6,

7,

11,

12,

14,

15]. Unfortunately, assessment of the often functionally difficult task of getting up from the floor in older adults is not frequently performed, limiting opportunities to address related impairments for maximizing patient safety and quality of life [

16,

17]. Evidence-based guidance for anticipating how quickly and in what way a patient might get up from the floor, along with an understanding of differences in lower extremity demand between the 5XSTS and half-kneeling FT strategy, may improve FT integration into clinical practice. Based on study findings, neither FT speed nor strategy can be anticipated with commonly used self-report measures or the 5XSTS test, though insights were gained regarding characteristics of older adults who might choose certain strategies. Differences found in lower extremity demands between the 5XSTS and the half-kneeling FT strategy (

Figure 3), and in knee mobility between FT strategies (

Figure 2), can assist with FT training and interventions. Overall, study findings provide evidence for clinical decision-making related to FT assessment, instruction, and exercise prescription.

Study findings showed a significant and moderate association of FT time with age and 5XSTS time, along with a trend toward a significant and moderate association with peak knee power during the 5XSTS task. Previous studies have also shown an association between longer FT times and advanced age and decreased lower extremity strength as indicated by longer 5XSTS times [

6,

7,

12,

15]. Mean FT times from a supine position in this study ranged from 2 to 10.7 s, with an average of 4.7 (SD 2.1) seconds, consistent with that previously demonstrated in healthy older adults [

12,

14]. All participants in this study performed the 5XSTS in under 13.6 s, a cut-off time previously shown to discriminate against the ability to perform a FT without the assistance of a chair [

5,

6]. The association between FT time and greater knee extension power, during the 5XSTS is a novel finding. Findings suggest that training knee extension power in older adults may be influential in facilitating quicker transfers from the floor, though more research is warranted.

No self-report measures utilized in this study were significantly associated with FT time, though previous research has shown FoF to be associated with difficulty getting up from the floor [

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This study included an active population with self-reported SE and PF above established norms, low FoF, and physical performance tests within age-related norms. Thus, in a healthy older adult population with relatively high SE and baseline physical activity, FT time may be discriminated more by physical ability than patient perceptions of self. Emphasis in clinical practice should remain focused on building and preserving physical capacity to perform the FT task in active older adults [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

15,

22,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This study also did not collect information on participants’ fall history, which may have been a factor in this study’s findings. Further research is warranted to investigate relationships between FT abilities and self-report measures in older adults with more broad ranges (i.e., spanning lower and higher scores) for SE, PF, and FoF responses and 5XSTS performance.

Based on study findings, various self-selected FT strategies involve different peak knee joint angles and time to complete, and individuals who choose different FT strategies differ slightly in FES-I scores. Participants who performed the quadruped strategy demonstrated less knee flexion than the roll-over and half-kneel strategy. Those who performed the quadruped strategy also reported slightly higher FoF and took longer to perform the FT task than those using the other two strategies. Results suggest that clinicians may be able to anticipate the use of the quadruped FT strategy in community-dwelling older adults with greater FoF and less knee mobility, and that these individuals may take slightly longer to get up from the floor. Clinical judgment is necessary to make decisions related to optimizing a self-selected FT strategy or facilitating the ability to perform the more commonly instructed half-kneel strategy. Further research is warranted to gain additional insights into why participants choose a certain strategy and to investigate additional differences between strategies, such as factors related to dynamic postural control and peak lower extremity strength and power.

Study findings indicate that the 5XSTS and instructed FT tasks are biomechanically different when upper extremity use is eliminated in both tasks, with greater demand at the ankle and hip in the instructed FT and greater demand at the knee during the 5XSTS. The instructed FT involved greater peak hip flexion mobility and hip extension torque than the 5XSTS. The 5XSTS utilized greater peak knee extension torque and power than the instructed FT task. Research supports the use of the 5XSTS to reliably predict FT ability; however, the lower extremity demands of the 5XSTS do not entirely mimic that of the commonly instructed half-kneeling FT strategy when performed without upper extremity assistance. Though some older adults may not be able to get up from the floor without upper extremity support, which was observed in this study, daily life scenarios that require picking up an object with both arms could require getting up from the floor in such a manner. Thus, it is imperative to understand the lower extremity demands during a FT performed without using the upper extremities. Based on study findings, clinicians may consider prescribing exercises that increase the hip and ankle strength and power demands beyond that of the 5XSTS to maximize FT ability. Further research is warranted to investigate the role and contributions of the upper extremities when used while getting up from the floor.

This study is not without limitations. Participants were from a convenience sample of community-dwelling and active older adults 50-80 years old without significant cognitive impairment. All participants performed the self-selected FT task independently. Thus, study findings cannot be applied to other populations of different age ranges, physical activity levels, health status, or FT ability levels. This study defined three commonly used FT strategies in older adults based on the body position prior to standing. Strategy categorization may therefore differ from studies that define the FT strategy based on movements identified earlier in the transition from supine to standing. This study also compared the lower extremity demands between the 5XSTS test and a single, commonly used and instructed FT strategy, preventing comparisons to other FT strategies performed by older adults. Lastly, this study required the elimination of upper extremity use during the half-kneeling FT strategy to quantify lower extremity demand through biomechanical analysis. Further research is warranted to investigate the effects of upper extremity support on floor transfer performance.

5. Conclusions

Study findings provide insights into how self-report measures may allow clinicians to anticipate strategies used by older adults to get up from the floor. Differences found in lower extremity biomechanical demands between the 5XSTS and the half-kneeling FT strategy provide direction for optimizing exercise prescription to meet the physical demands of getting up from the floor. Results provide evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making related to FT training and exercise prescription to maximize functional independence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and T.W.; methodology, L.S. and T.W..; formal analysis, L.S.; investigation, L.S. and T.W.; resources, L.S. and T.W.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S. and T.W.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and T.W.; visualization, L.S.; supervision, L.S. and T.W; project administration, L.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of George Fox University (Study Number 2231152, 11/13/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robin Dorociak for technical support, Ryan Jacobson for manuscript editing support, and Shelby Peerboom, Marisa Doveri, Brianna Helton, and Emily Thomson for assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FT |

Floor transfer |

| 5XSTS |

5-time sit-to-stand |

| ANOVA |

One-way analysis of variance |

| FES-I |

Falls Efficacy Scale International |

| FoF |

Fear of Falling |

| SE |

Self-efficacy |

| PF |

Physical function |

| SLUMS |

Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam |

| PROMIS |

Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System |

| RAPA |

Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity |

| CAT |

Computer Adaptive Testing |

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. Older Americans month: data on aging. Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/older-aging/data.html. Accessed September 9, 2024.

- National Council on Aging. Nursing homes costs. Available at: https://www.ncoa.org/adviser/local-care/nursing-homes-costs/#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20cost%20of,2023%20Cost%20of%20Care%20Survey. Accessed September 9, 2024.

- Genworth Financial. Cost of care trends and insights. Available at: https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care/cost-of-care-trends-and-insights. Accessed September 9, 2024.

- Haddad YK, Miller GF, Kakara R, et al. Healthcare spending for non-fatal falls among older adults, USA. Injury Prevention. 2024;30:272-276. [CrossRef]

- Ardali G, Brody LT, States RA, Godwin EM. Reliability and validity of the floor transfer test as a measure of readiness for independent living among older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2019;42(3):136–147. [CrossRef]

- Ardali G, States RS, Brody LT, Godwin EM. Characteristics of older adults who are unable to perform a floor transfer: considerations for clinical decision-making. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2020;42(3):62-70. [CrossRef]

- Bergland A, Laake K. Concurrent and predictive validity of “getting up from lying on the floor,”. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:181-185. [CrossRef]

- Murphy MA, Olson SL, Protas EJ, Overby AR. Screening for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Aging Phys Act. 2003;11:66-80. [CrossRef]

- Tinetti ME, Liu WL, Claus EB. Predictors and prognosis of inability to get up after falls among elderly persons. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;269(1);65-70. [CrossRef]

- De Brito LBB, Ricardo DR, de Araujo DSMS, Ramos PS, Myers J, de Araujo CGS. Ability to sit and rise from the floor as a predictor of all-cause mortality. Euro J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(7);892-898. [CrossRef]

- Taulbee L, Trapuzzano A, Nguyen T. Geriatric functional milestones: promoting movement while aging. GeriNotes. 2021;28(4);26-28.

- Alexander NB, Ulbrich J, Raheja A, Channer D. Rising from the floor in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45;564-569. [CrossRef]

- Ardali G, States RS, Brody LT, Godwin EM. The relationship between performance of sit-to-stand from a chair and getting down and up from the floor in community-dwelling older adults. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;38(6):818-829. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon RW, Lusardi MM. Getting up from the floor: determinants and techniques among healthy older adults. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009;20(4):233-242. [CrossRef]

- Fleming J. Inability to get up after falling, subsequent time on floor, and summoning help: Prospective cohort study in people over 90. BMJ. 2008;337:a2227. [CrossRef]

- Simpson JM, Salkin S. Are elderly people at risk of falling taught how to get up again? Age Ageing. 1993;22(4):294-6. [CrossRef]

- Swancutt DR, Hope SV, Kent BP, Robinson M, Goodwin VA. Knowledge, skills and attitudes of older people and staff about getting up from the floor following a fall: a qualitative investigation. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(385);1-10. [CrossRef]

- Delbaere K, Close J, Mikolaizak A, Sachdev P, Brodaty H, Lord S. The falls efficacy scale international (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age Ageing. 2010;39:210-216. [CrossRef]

- Dewan N, MacDermid JC. Fall Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). J Physiother. 2014;60(1):60. [CrossRef]

- Hauer K, Yardley L, Beyer, N, Kempen G, Dias N, Campbell M, Becker C, Todd C. Validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale and Falls Efficacy Scale International in geriatric patients with and without cognitive impairment: Results of self-report and interview-based questionnaires. Gerontology. 2010;56(2): 190-199.. [CrossRef]

- Hauer KA, Kempen GM, Schwenk M, et al. Validity and sensitivity to change of the falls efficacy scale international to assess fear of falling in older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2011;57(5):462-472. [CrossRef]

- Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45:239-243. [CrossRef]

- Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing. 2005;34(6):614-619. [CrossRef]

- Samant, P, Mohan, V, Shyam A, and Sancheti, P. Study of Relationship Between Fear of Falling & Ability to Sit On and Rise From the Floor in Elderly Population. Int J Physiother Res. 2019;7(4):3818-3183. [CrossRef]

- Computer adaptive tests. HealthMeasures. Updated July 31, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=164&Itemid=1133.

- Gruber-Baldini AL, Velozo C, Romero S, Shulman LM. Validation of the PROMIS® measures of self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(7):1915-1924. [CrossRef]

- Houck J, Kang D, Cuddeford T. Do clinical criteria based on PROMIS outcomes identify acceptable symptoms and function for patients with musculoskeletal problems. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;55:102423. [CrossRef]

- Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:89-102. [CrossRef]

- Deyo RA, Katrina Ramsey, Buckley DI, et al. Performance of a patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) short form in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2016;17(2):314-324. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon RW. Measurement of sit-to-stand among older adults. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2012;28(1):11-16. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, RW. Reference values for the five-repetition sit-to-stand test: a descriptive meta-analysis of data from elders. Percept Mot Skills. 2006;103(1): 215-222. [CrossRef]

- Schaubert, KL, and Bohannon, RW Reliability and validity of three strength measures obtained from community-dwelling elderly persons. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(3):717-720. [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyer MR, Neil B, Alexander NB, Nyquist LV, Medell JL, Koreishi A. Floor-rise strategy training in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1702-1706. [CrossRef]

- Klima DW, Anderson C, Samrah D, Patel D, Chui K, Newton R. Standing up from the floor in community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24:207-213. [CrossRef]

- Schwickert L, Oberle C, Becker C, et al. Model development to study strategies of younger and older adults getting up from the floor. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;27:277-287. [CrossRef]

- SH Tariq, N Tumosa, JT Chibnall, HM Perry III, and JE Morley. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the MiniMental Status Examination (MMSE) - A pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych 2006;14:900-10. [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:11-117. [CrossRef]

- Liguori G, Feito Y, Fountaine C, Roy, B ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2022.

- Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, Williams B, Patrick MAJMB. The rapid assessment of physical activity (RAPA) among older adults. PREVENTING CHRONIC DISEASE: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2006;3(4):1-8.

- University of Washington Research Health Promotion Research Center. How physically active are you? An assessment of level and intensity of physical activity. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/hprc/rapa.

- Intro to PROMIS. HealthMeasures. Updated May 16, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis.

- General self-efficacy and self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. HealthMeasures. Updated October 25, 2017. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Self_Efficacy_Managing_Chronic_Conditions_Scoring_Manual.pdf.

- Physical function. HealthMeasures. Updated June 20, 2020. Accessed October 30, 2024.https://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Physical_Function_Scoring_Manual.pdf.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-1194. [CrossRef]

- Schalet BD, Hays RD, Jensen SE, Beaumont JL, Fries JF, Cella D. Validity of PROMIS physical function measured in diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:112-118. [CrossRef]

- Broderick JE, Schneider S, Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Validity and reliability of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system instruments in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(10):1625-1633. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).