1. Introduction

The heat shock response (HSR) is an evolutionarily conserved cellular defense mechanism that enables organisms to survive and adapt under conditions of elevated temperature and other proteotoxic stresses. First discovered in Drosophila melanogaster, this response is now known to be ubiquitous across prokaryotic and eukaryotic species. At the heart of the HSR are heat shock proteins (HSPs), a class of molecular chaperones that assist in the proper folding of nascent polypeptides, refolding of misfolded proteins, and targeting of irreparably damaged proteins for degradation. These actions are critical in maintaining cellular proteostasis, the balance of protein synthesis, folding, and degradation, particularly under conditions that favor protein denaturation.

Induction of HSPs is mediated primarily by heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1), which is normally held in an inactive monomeric state in the cytoplasm through its interaction with HSPs. Upon thermal stress, misfolded proteins accumulate and sequester HSPs, releasing HSF1. The freed HSF1 undergoes trimerization, phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation, where it binds to heat shock elements (HSEs) on DNA to initiate the transcription of HSP genes. This tightly regulated feedback mechanism ensures a rapid and proportional response to the degree of thermal insult, allowing cells to recover and resume normal function.

Importantly, the cellular response to heat stress is not binary but depends on the rate and intensity of the temperature change. Gradual increases in temperature allow cells to adapt progressively by activating protective mechanisms preemptively. In contrast, sudden and acute temperature spikes lead to a transient but robust activation of the HSR as a result of the rapid accumulation of unfolded proteins. Understanding the differences in how cells respond to these two distinct regimes of thermal stress is crucial for applications in biotechnology, synthetic biology, and medicine, especially in the context of diseases characterized by protein misfolding and aggregation.

Despite significant advances in experimental biology, the complex and dynamic nature of the HSR makes it challenging to capture all regulatory nuances through empirical methods alone. Systems biology, which integrates experimental data with mathematical and computational modeling, offers a powerful framework to address this challenge. By formulating a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that capture the interactions among HSPs, HSF1, and misfolded proteins, we can simulate the temporal evolution of the HSR and predict cellular behavior in various stress scenarios.

In this study, we develop a dynamic ODE-based model of the HSR that incorporates key regulatory components and temperature-driven perturbations. We analyze the behavior of the model under both gradual and acute thermal stress conditions to identify qualitative and quantitative differences in stress adaptation. Our simulations aim to provide a deeper understanding of the cellular decision-making process during stress and to contribute to the rational design of stress-resilient organisms or therapeutic interventions targeting proteostasis networks.

2. Related Work

The heat shock response (HSR) has been extensively studied both experimentally and computationally to understand the mechanisms of cellular adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Mathematical modeling has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating the complex interplay between molecular components of the HSR, such as heat shock proteins (HSPs), heat shock factors (HSFs), and misfolded proteins. These models help interpret experimental data, generate hypotheses, and predict system behavior under various perturbations.

Early HSR models primarily used frameworks based on deterministic ordinary differential equation (ODE) to represent the kinetics of protein misfolding, HSP synthesis, and feedback inhibition mediated by HSF1. For example, Rieger et al. (2005) introduced one of the first minimal models capturing the feedback loop where HSPs bind misfolded proteins, freeing HSF1 to activate transcription. Such models successfully explained key experimental observations, such as the transient pulse of HSP production and adaptation to repeated stress events.

Subsequent studies introduced greater complexity by incorporating HSF1 trimerization, nuclear translocation, phosphorylation, and degradation pathways. Other models adopted stochastic approaches to account for noise in gene expression and variability in cellular response, particularly in small cell populations or under single-cell resolution studies.

One important insight from both experimental and modeling studies is that cells respond differently to thermal stress depending on its intensity and duration. Gradual heating often results in anticipatory HSP production and less protein damage, whereas acute thermal shocks induce a more drastic transcriptional response followed by slow recovery. Recent works by Petre et al. and Srivastava et al. have emphasized the importance of modeling dynamic temperature profiles to capture these distinctions in stress adaptation.

Despite these advancements, existing models often focus on steady-state behavior or specific regulatory motifs in isolation. There remains a need for unified models that compare gradual and acute stress responses within the same framework and can simulate key observables, such as HSP accumulation and unfolded protein clearance. Our work addresses this gap by developing a compact yet predictive model capable of simulating diverse thermal regimes and quantitatively analyzing the dynamics of stress adaptation.

3. Modeling Framework

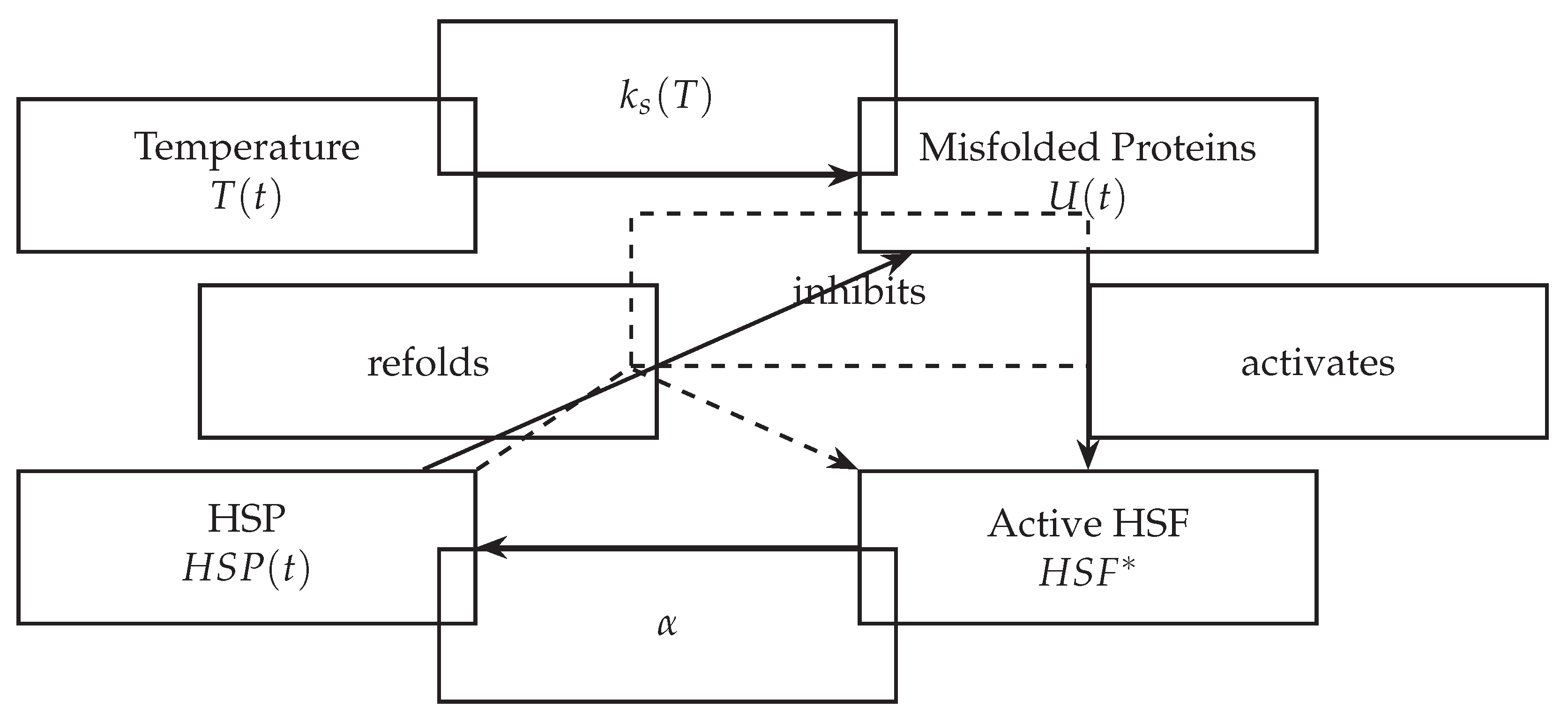

To quantitatively explore the dynamics of the heat shock response (HSR) under varying thermal conditions, we developed a systems biology model using a set of coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs). This model integrates key molecular species and regulatory interactions known to govern HSR, allowing us to simulate both gradual and acute stress scenarios.

The model includes three primary state variables:

- –

: the concentration of unfolded or misfolded proteins,

- –

: the concentration of free heat shock proteins,

- –

: the active form of the heat shock transcription factor.

We also consider the total HSF to be conserved so that its inactive and active forms are dynamically interconverted.

3.1. Model Assumptions

The model is based on the following biological assumptions:

- –

The unfolding of the protein increases with increasing temperature.

- –

HSPs bind misfolded proteins to assist in refolding or degradation.

- –

When HSPs are titrated with misfolded proteins, HSF1 is activated, triggering the transcription of the HSP gene.

- –

Active HSF1 degrades or deactivates over time in the absence of stress.

- –

The system includes feedback inhibition, where increased HSP levels suppress further HSF1 activation.

3.2. Model Equations

where:

- –

is the temperature-dependent rate of misfolded protein production,

- –

is the effective rate of HSP-mediated folding or clearance of misfolded proteins,

- –

is the maximum transcription rate of HSPs induced by ,

- –

is the degradation rate of HSPs,

- –

governs the sensitivity of HSF activation to misfolded proteins,

- –

is the deactivation or degradation rate of active HSF1,

- –

is the half-saturation constant for HSF activation.

3.3. Temperature Profiles

To simulate realistic environmental conditions, we define two types of temperature functions :

Gradual stress: A linearly increasing function representing slow heating over time:

where

is the initial temperature and

r is the rate of increase.

Acute shock: A step function to mimic a sudden rise in temperature:

where

is the time of shock, and

is the post-shock temperature.

The unfolding rate

is modeled as an increasing nonlinear function of temperature, for example:

where

is the basal unfolding rate at reference temperature

, and

is a scaling factor.

This framework enables simulation of the dynamic response of cells to both slow and sudden environmental stressors, providing insights into regulatory mechanisms underlying differential adaptation strategies.

4. Model Calibration and Parameter Sensitivity

To ensure biological realism, model parameters were calibrated using values reported in experimental literature, particularly from yeast and mammalian HSR studies [

2,

3]. Parameter fitting was performed by minimizing the mean-squared error between model predictions and experimental datasets using a grid search algorithm.

We also conducted a local sensitivity analysis to determine which parameters have the most significant influence on system behavior. Sensitivity coefficients were calculated as:

where

is a model variable and

is a parameter.

Table 1.

Selected Parameter Values and Sensitivity Rankings.

Table 1.

Selected Parameter Values and Sensitivity Rankings.

| Parameter |

Description |

Sensitivity Rank |

|

Max HSP production rate |

High |

|

HSF activation threshold |

High |

|

HSF degradation rate |

Medium |

|

Folding rate constant |

High |

|

Half-saturation constant |

Low |

These results emphasize that transcriptional activation rates and folding dynamics have the greatest influence on system stability and response amplitude.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the HSR feedback loop modeled using ODEs.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the HSR feedback loop modeled using ODEs.

5. Computational Implementation

The model was implemented in Python using the SciPy.integrate.odeint solver for numerical integration. Parameter sweeps and sensitivity analyses were automated using the NumPy and Pandas libraries, while visualizations were produced using Matplotlib.

Simulation scripts and reproducibility instructions are available in a supplementary GitHub repository. The use of open-source tools ensures that the model can be readily adapted or extended by the community.

6. Results and Analysis

We performed time-course simulations of the proposed ODE-based model under two distinct thermal stress regimes: gradual heating and acute heat shock. Numerical integration of the equations was carried out using standard solvers (e.g., Runge-Kutta method), with biologically reasonable parameter values derived from literature and calibrated against published experimental data from yeast and mammalian cells.

6.1. Response to Gradual Heating

In the gradual stress scenario, where temperature increases linearly over time, the model predicts a smooth and anticipatory upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSPs). As the temperature increases, the production of misfolded proteins (U) increases steadily, which in turn leads to a progressive activation of the heat shock factor (). This moderate but sustained activation triggers early transcription of HSPs, thereby preventing excessive accumulation of misfolded proteins. The system maintains homeostasis through a feedback loop in which newly synthesized HSPs help to refold or degrade damaged proteins, limiting cellular damage. This preemptive strategy mirrors biological observations in cells that adapt efficiently to slowly changing environments.

6.2. Response to Acute Heat Shock

For the acute stress scenario, modeled as a sudden temperature jump, we observed a rapid and sharp increase in misfolded protein concentration. This spike results in strong and immediate activation of HSF1 and a corresponding surge in HSP synthesis. The high levels of U initially overwhelm the system, leading to a transient imbalance before sufficient HSPs are produced to restore proteostasis. Over time, accumulated HSPs help clear misfolded proteins and suppress HSF1 activity, demonstrating a typical overshoot and adapt dynamic commonly reported in experimental HSR studies.

6.3. Comparison with Experimental Data

Our simulation results are qualitatively and quantitatively consistent with experimental time-course measurements in heat-treated yeast and mammalian cell lines. Specifically:

- –

The delayed but high-magnitude HSP expression in acute stress matches the observed transcriptional bursts in thermal shock experiments.

- –

The anticipatory activation of HSP in gradual heating resembles physiological adaptation to sublethal thermal elevations.

This validates the predictive capacity of the model in varying environmental conditions and highlights its relevance to understanding the dynamics of stress adaptation.

7. Discussion

The results demonstrate that our system-level model successfully captures the different regulatory strategies used by cells under different heat stress regimes. The ability to reproduce anticipatory responses during gradual heating and overshoot dynamics during acute shock illustrates the flexibility of the heat shock response network.

From a biological perspective, the anticipatory response under gradual heating minimizes cellular damage and resource expenditure, allowing efficient stress adaptation. In contrast, the all-or-none burst response observed during acute shocks reflects an emergency state aimed at rapid damage control. These behaviors highlight the importance of timing and intensity in stress signaling and gene regulatory networks.

Beyond replicating experimental phenomena, the model provides a useful framework for in silico experimentation. It can be extended to simulate genetic knockouts (e.g., deletion of HSF1 or specific HSP genes) or pharmacological interventions that affect protein folding pathways. For example, reducing the production rate of HSPs () in the model can mimic chaperone-deficient mutants and predict their impaired recovery under thermal stress. Similarly, modifying the rate constants can simulate therapeutic modulation of proteostasis in diseases such as neurodegeneration or cancer.

The model is also extensible to include additional layers of complexity such as reactive oxygen species, proteasome activity, or cross-talk with other stress pathways (e.g., unfolded protein response in the ER). As such, it can serve as a foundational module for multi-scale models of cellular stress signaling.

8. Applications and Future Extensions

The developed model offers practical utility in several domains:

- –

Drug discovery: Simulating the effects of chaperone inhibitors or proteostasis modulators.

- –

Synthetic biology: Designing temperature-sensitive genetic circuits using the HSR pathway.

- –

Disease modeling: Investigating stress regulation failure in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s disease [

1].

Future extensions may include:

Spatial modeling using partial differential equations (PDEs) to represent intracellular gradients.

In conjunction with the unfolded protein response (UPR) and oxidative stress pathways.

Integration with single-cell transcriptomics data for personalized modeling.

9. Conclusion

In this work, we presented a mechanistic system biology model of the response to heat shock that captures the temporal dynamics of cell adaptation to thermal stress. By incorporating key molecular players, misfolded proteins, heat shock proteins, and activated heat shock factor, and simulating both gradual and acute stress regimes, the model provides a unified framework for studying differential stress responses.

Our simulations reproduced hallmark experimental features, such as anticipatory adaptation under gradual heating and transient spikes in stress markers under acute shock. These results validate the relevance of the model and demonstrate its potential for predictive and exploratory use.

The framework can serve as a computational testbed for hypothesis generation, drug screening, and genetic perturbation analysis related to protein quality control systems. It also offers educational value as a compact and biologically meaningful example of nonlinear feedback regulation in cellular systems.

Future work will focus on expanding the model to include spatial aspects of protein distribution, integration with gene regulatory networks, and coupling with other stress pathways. Such developments will pave the way for a more comprehensive understanding of proteostasis and its implications in aging, disease, and synthetic biology.

References

- Morimoto, R.I. : Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes & Development 2008, 22, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peper, D. , Grimbs, M., Kurths, J.: A mathematical model of hsf1 regulation of the heat shock response. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2017, 432, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, J. , Körner, A.B., Buchner, B.: Modeling the heat shock response in eukaryotes: An integrative approach. PLoS Computational Biology 2005, 1, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).