Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Enthalpy-Based EOS

2.1. Specifications for EOS

2.2. Temperature Dependent

3. Modeling Compaction Phase

3.1. Low Pressure Compaction

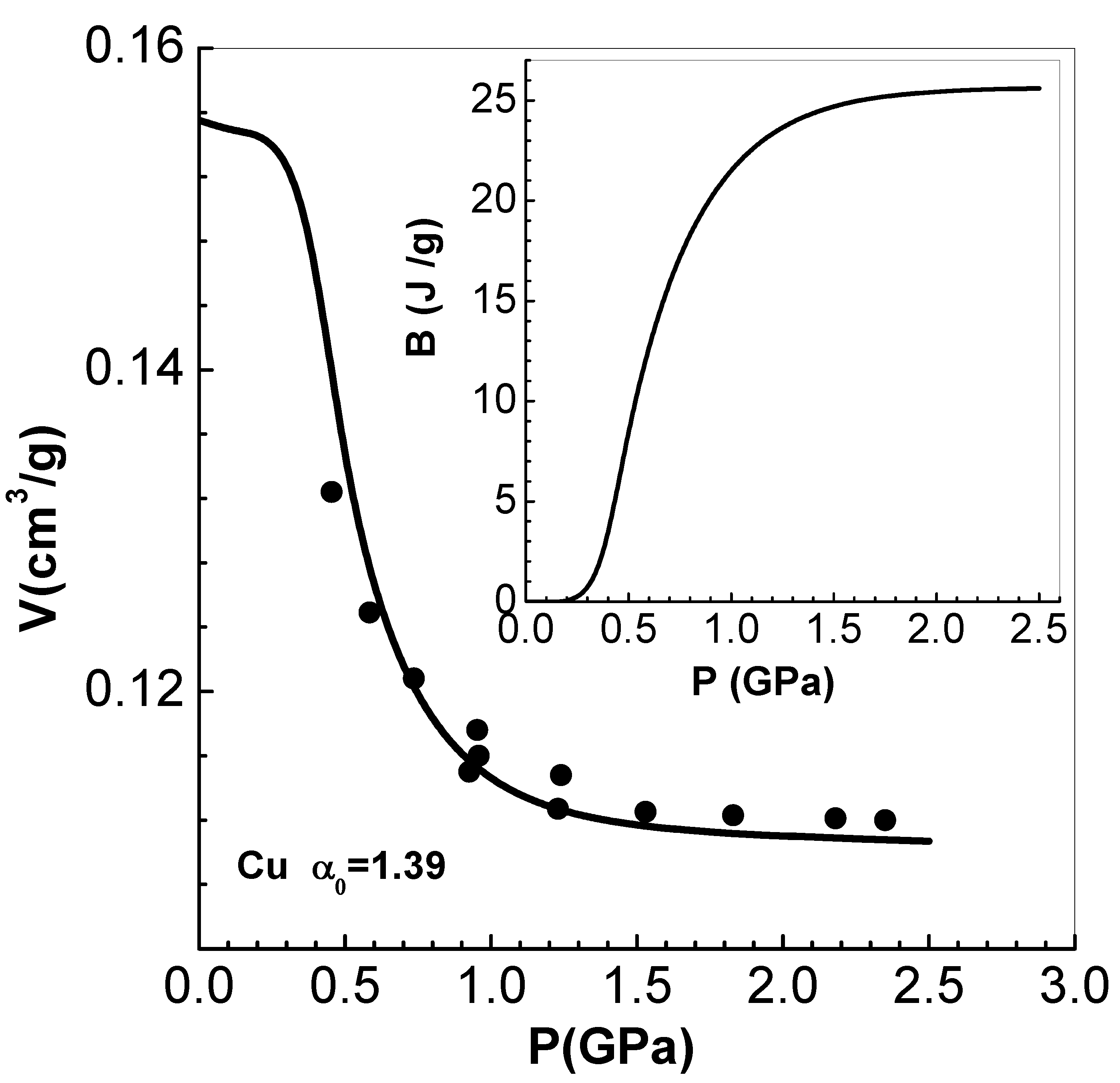

3.2. Menikoff’s Modified Model

4. Application to Lithium Deuteride

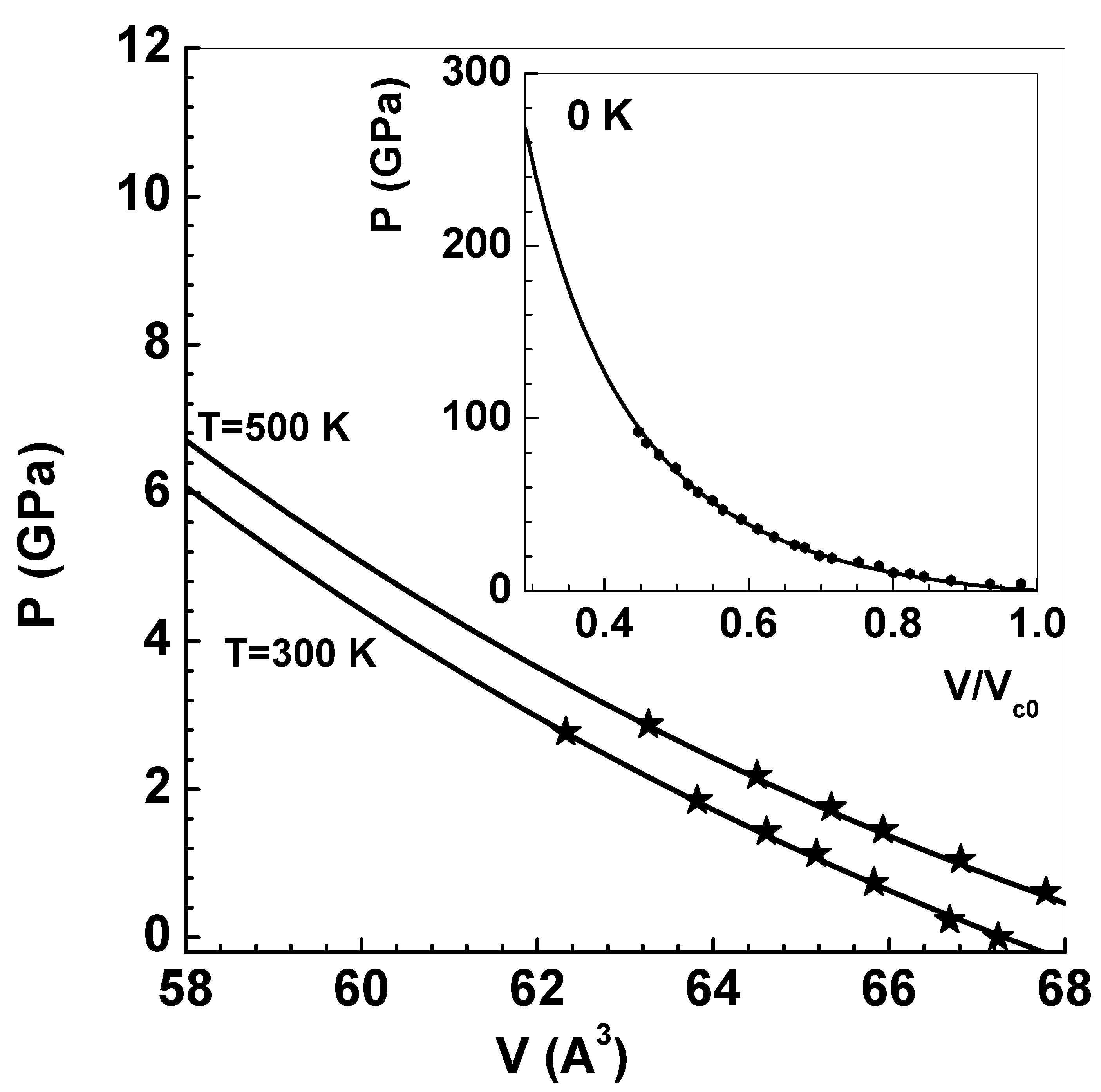

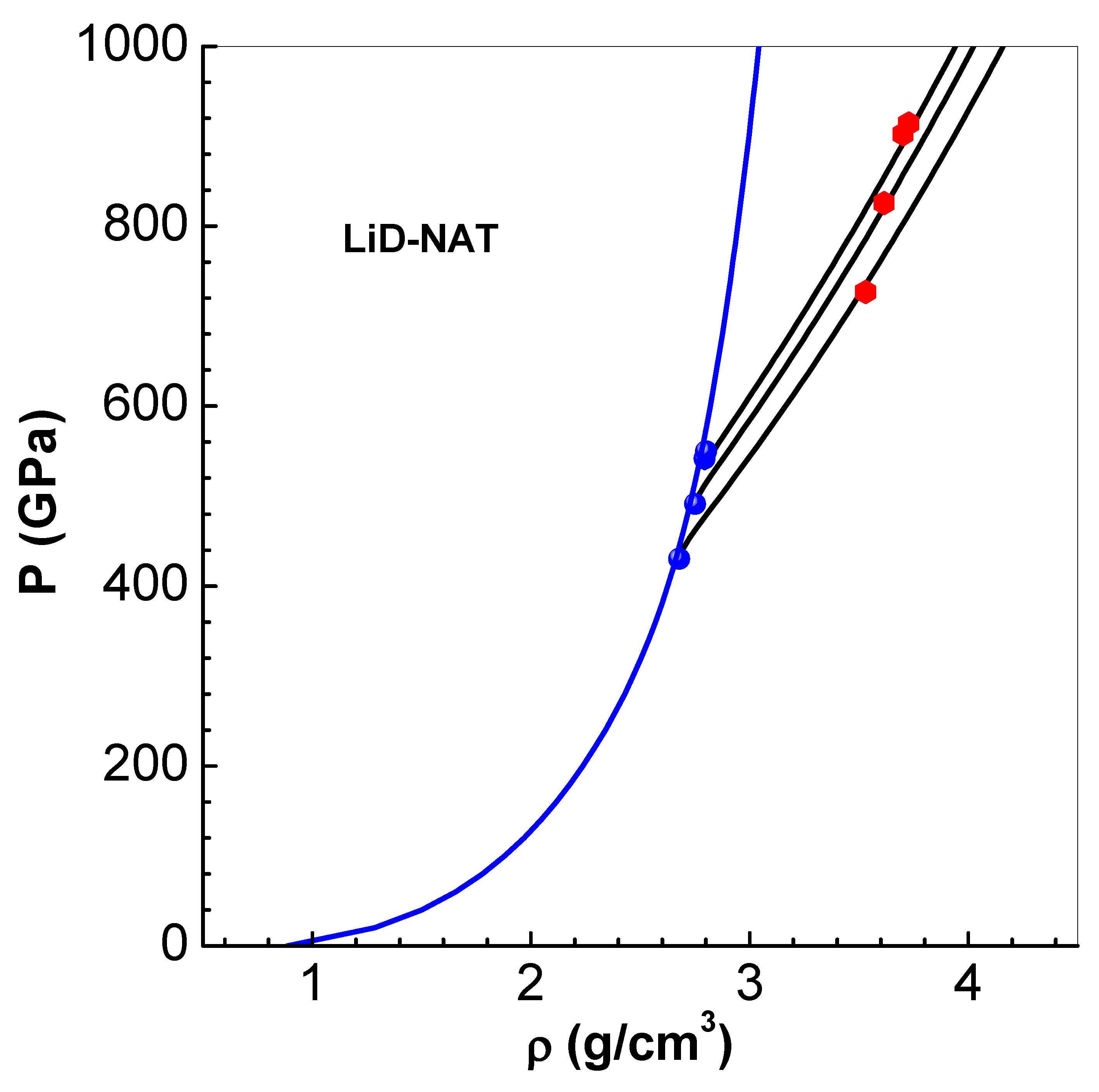

4.1. Isotherms of Natural LiD

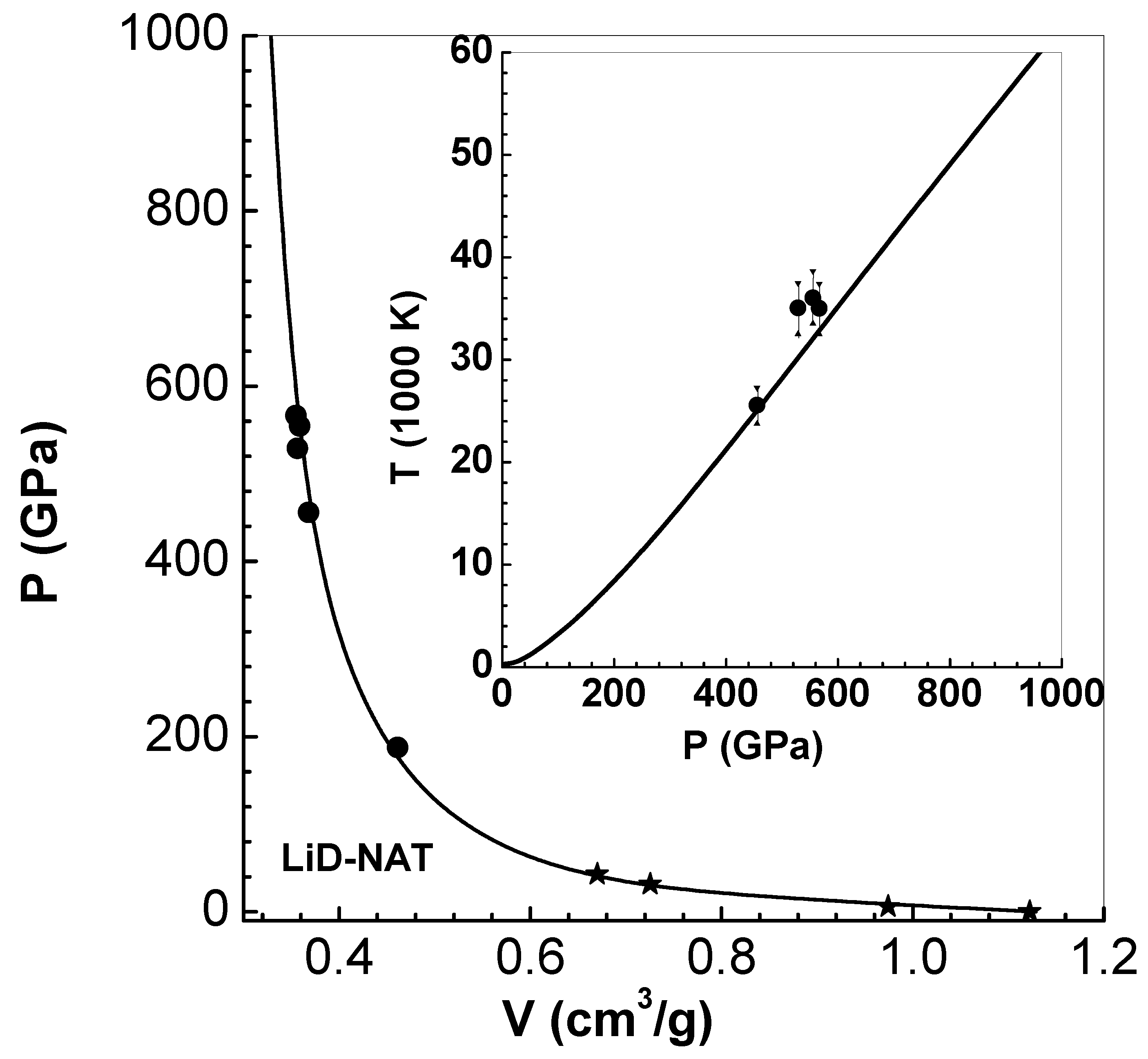

4.2. Principal Hugoniot of natural LiD

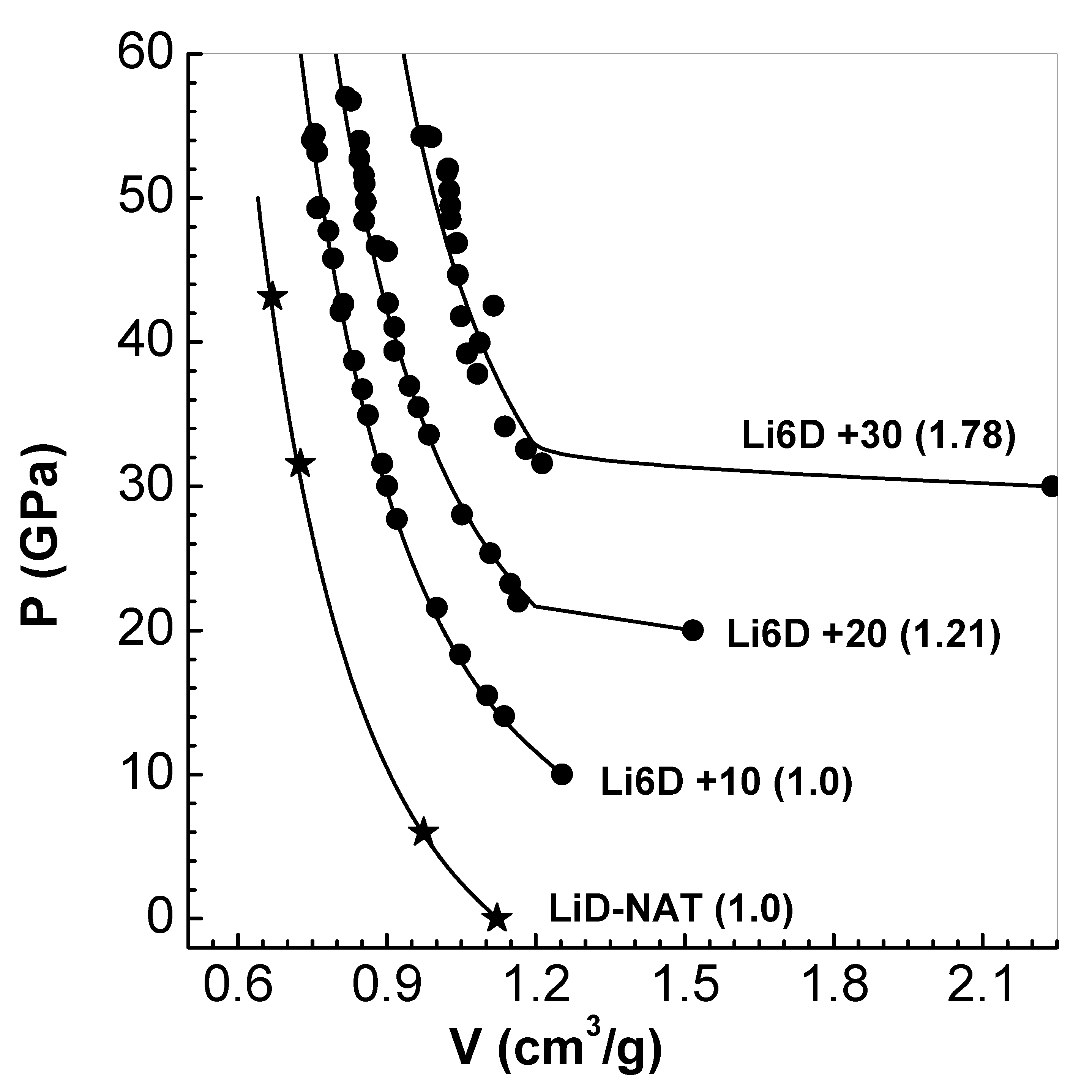

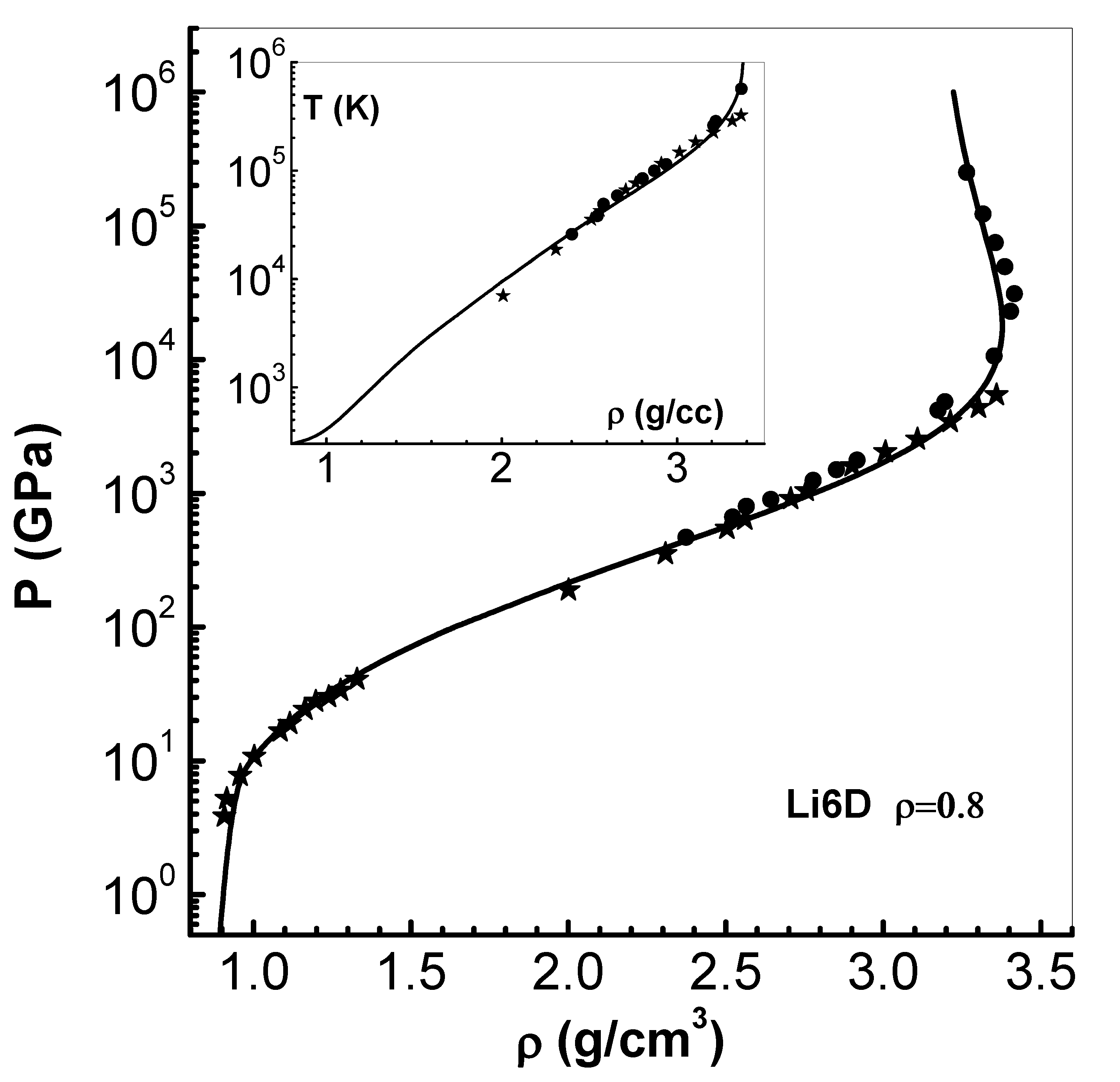

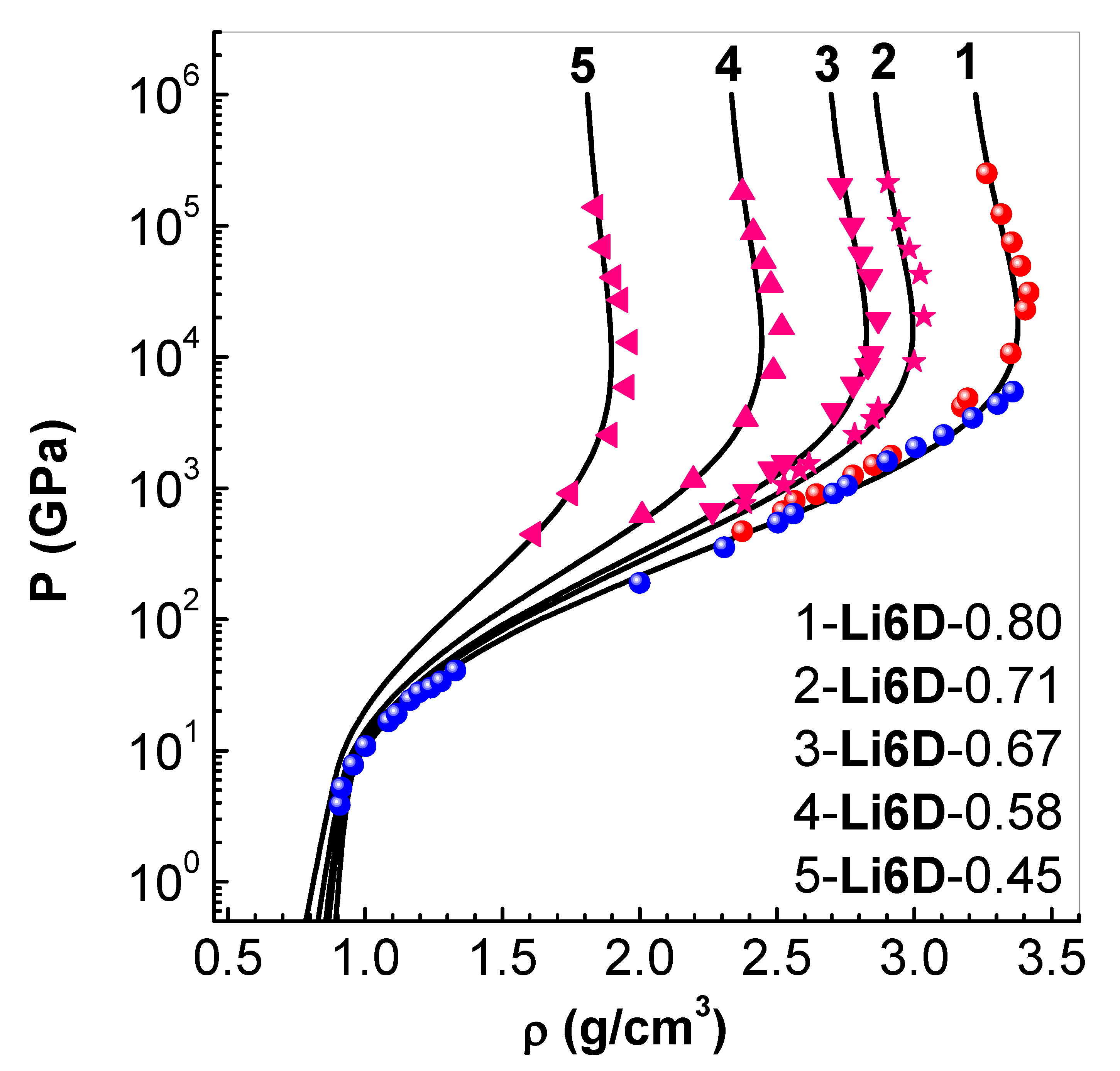

4.3. Solid and Porous Hugoniot

5. Implementation of EEOS in Euler Solver

5.1. Updating P and T

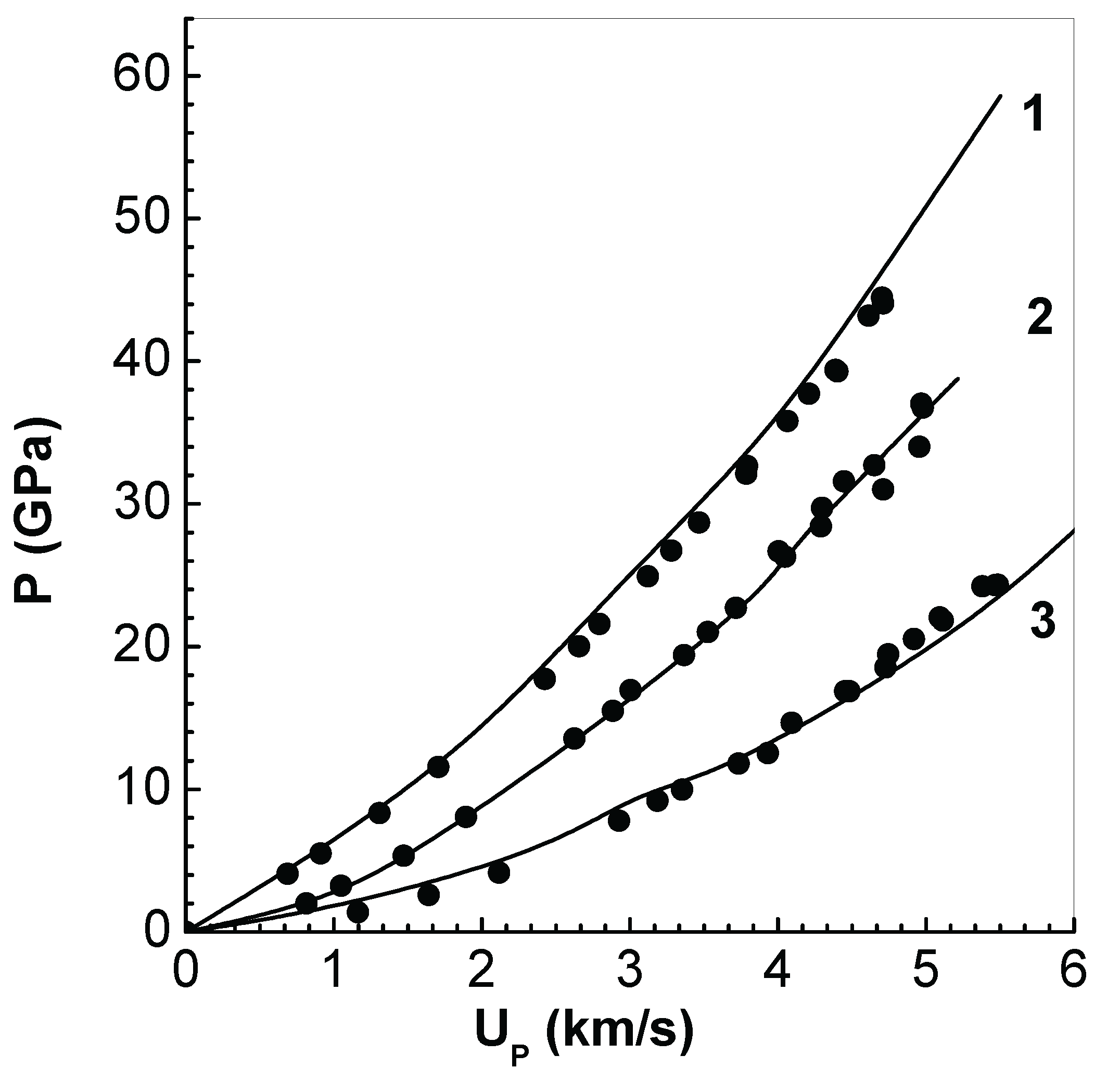

5.2. Shock Pressure Versus Fluid Velocity in

6. Summary

Appendix A. Simple EOS Models

Appendix A.1. Zero Temperature Isotherm

Appendix A.2. Ionic EOS

Appendix A.3. Ionic Grüneisen Parameter

| Material | C | S | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g cm−3 | GPa | k J g−1 | J g −1 K−1 | k m s−1 | ||||

| Cu | 8.93 | 134.8 | 5.19 | 5.302 | 0.3851 | 2.14 | 4.14 | 1.408 |

| LiD-N | 0.886 | 32.1† | 3.53† | 10.14 | 3.6312 | 1.04 | 0.610 | 1.101 |

| Li6D | 0.8 | 33.1 | 3.73 | 10.14 | 3.0932 | 1.22 | 0.659 | 1.095 |

| Material | Y | q | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPa | cm3 g−1 | K | K | K | ||||

| Cu | 0.448 | 0.1194 | 1358 | 343 | 0.901 | 0.7818 | 4.7 | |

| LiD-N | 0.001 | 1.185 | 588 | 1030 | 812 | 0.1 | 0.5740 | 5.1 |

| Li6D | 0.001 | 1.312 | 529 | 995 | 812 | 0.1 | 0.4476 | 5.1 |

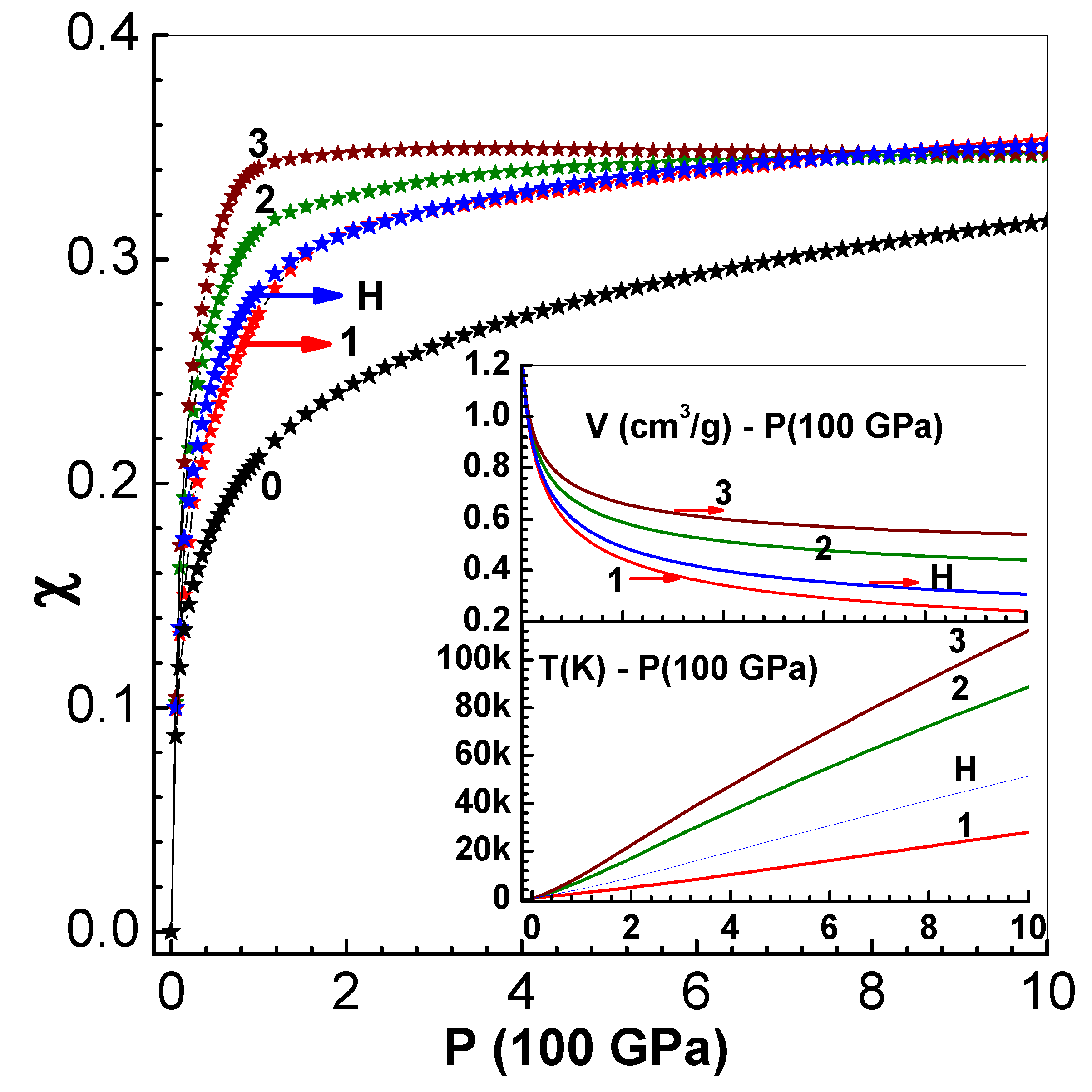

Appendix A.4. Electron-EOS-Fits

References

- Zel’ovich Ya B and Raizer Yu P 1966 Physics of Shock waves and High-Temperature Hydrodynamic Phenomena, volume-I (New York: Academic press.

- Sjostrom T 2019 in Shock Wave Phenomena in Granular and Porous materials, edited by Vogler T J and Anthony Fredenburg D (Switzerland AG, Springer Nature.

- More R M, Warren K H, Young D A and Zimmerman G B 1988 Phys. Fluid 31 3059.

- Wu Q and Jing F 1996 J. Appl. Phys. 80 434.

- Boshoff-Mostert L and Viljoen H J 1999 J. Appl. Phys. 86 124.

- Nagayama K and Kubota S 2014 J. Phys. Cond. Matt. Conf. Series 500 05203.

- Fenton G, Grady D and Vogler T 2015 J. dynamic behavior mater. 1 10.

- Nagayama K 2016 it J. Appl. Phys. 119 19590.

- Nagayama K 2017 it J. Appl. Phys. 121 17590.

- Nayak B and Menon S V G 2016 J. Appl. Phys. 119 12590.

- Nayak B and Menon S V G 2018 Shock Waves 28 14.

- Nayak B and Menon S V G 2017 AIP Advances 7, 04511.

- Nayak B and Menon S V G 2017 Physica B: Phys Cond. Matter 529 6.

- Nayak B and Menon S V G 2019 Mater. Res. Express 6 05551.

- Boris J P, Landsberg A M, Oran E S and Gardner J H 1993 LCPFCT – Flux-Corrected Transport Algorithm for Solving Generalized Continuity Equations NRL/MR/6410-93-7192.

- Menon S V G and Nayak B 2019 Condens. Matter, MDPI 4 7.

- Vinet P, Smith J R, Ferrante J and Rose J H 1987 Phys. Rev. B 35(4), 1945.

- Vinet P, Rose J R, Ferrante J and Smith J R 1989 J. Phys: Cond. Matter 1 1941.

- J. Hama and K. Suito 1996 J. Phys: Cond. Matter. 8 6.

- Kalitkin N N, Kuz’mina L V 1972 Sov. Phys. Solid State 13 1938.

- More R M 1979 Phys. Rev. A 19 1234.

- Kerley G I User’s Manual for PANDA II- A computer code for calculating equation of state 1991 SAND88-229.UC-405.

- Menon S V G 2021 Condensed Matter (MDPI) 6 6.

- Johnson J D 1991 it High Pressure Research 6 27.

- Fleche J L 2002 Phys. Rev. B 65, 245116.

- Burakovsky L and Preston D L 2004 J. Phys. and Chem.of Solids 65 158.

- Latter R 1955 Phys. Rev. 99 185.

- Menon, SVG 2025 Preprints.org (ID: preprints-154395). [CrossRef]

- Brachman M 1951 Phys. Rev. 84, 1263.

- Gilvarry J J 1954 Phys. Rev. 96, 934.

- McCloskey D J 1964 An analytic formulation of Equations of state RM-3905-PR.

- Kormer S B, Funtikov A I, Urlin V D and Kolesnikova A N 1962 Sov. Phys. JETP 15, 47.

- Carroll M M and Holt A C 1972 J. Appl. Phys. 43 1626.

- Davison L 2008 Fundamentals of Shock Wave Propagation in Solids (page.308) ( Berlin: Springer Verlag.

- Boade R R 1970 J. Appl. Phys. 41 454.

- Li J H, Liang S H, Guo H B and Liu B X 2007 Journal of Alloys and Compounds 431 2.

- Menikoff R and Kober E 2000 AIP Conference Proceedings 505 129. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhao Y, Wang Y and Daemen L 2008 J. Appl. Phys. 103 09351.

- Loubeyre R, Le Toullec R, Hanfland M, Ulivi L, Datchi F and D. Hausermann D, 2008 Phys. Rev. B 57 1040.

- Knudson M D, Desjarlais M P and Lemke R W 2016 J. Appl. Phys. 120 23590.

- Marsh S P 1980 LASL Shock Hugoniot Data (California: University of California Press.

- Sheppard D, Kress J D, Crockett S, and Collins L A 2014 Phys. Rev. E 90, 06331.

- Menon S V G and Nayak B 2020 Advances in Engineering Research 41 (Chapter-9) (Nova Publishers.

- Holmes N C, Rose M and Nellis W J 1995 Phys. Rev. B 95, 15835.

- Antia H M 1993 Astrophys. J. Suppl. Series 84, 10.

- More R M 1985 Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics, Academic Press, INC. San Diego, USA 21, 30.

- Gilvarry J J and March N H 1958 Phys. Rev. 112, 140.

- Gilvarry J J 1969 J. Chem. Phys. 51, 934.

| 0 | 3.3623507 | 6.1852324 | 31.183606 | 13.860657 |

| 1 | -401.07293 | 3877.2639 | 3164.4352 | 9610.8263 |

| 2 | 2.8182514 | -0.62899210 | 7.5243122 | -1.2048560 |

| 3 | 2.9748254 | -0.71993507 | 6.9731093 | -1.1227845 |

| H | -0.42562677 | 24.168165 | 20.940494 | 62.256942 |

| 1 | 2564.6813 | -393.97924 | 701.49802 | 0.23548460 |

| 2 | 6027.1119 | 1319.3867 | 775.26105 | 0.098925459 |

| 3 | 7516.4853 | 2134.3297 | 1344.5431 | 0.13534592 |

| H | 3662.1612 | 369.97967 | 173.67388 | 0.038177599 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).