Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Wound Ballistics

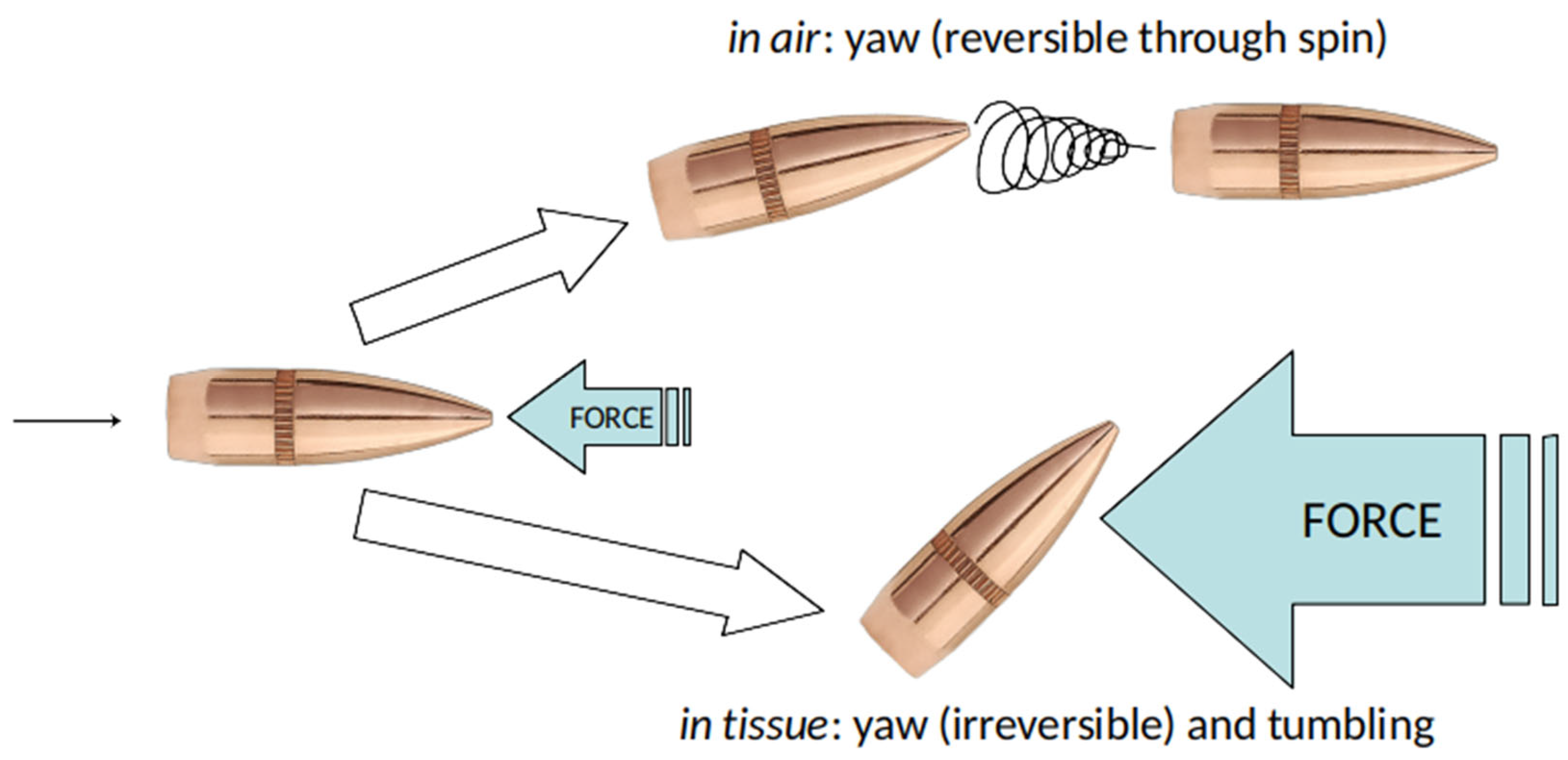

2.1. Dynamics of Penetrating Projectiles

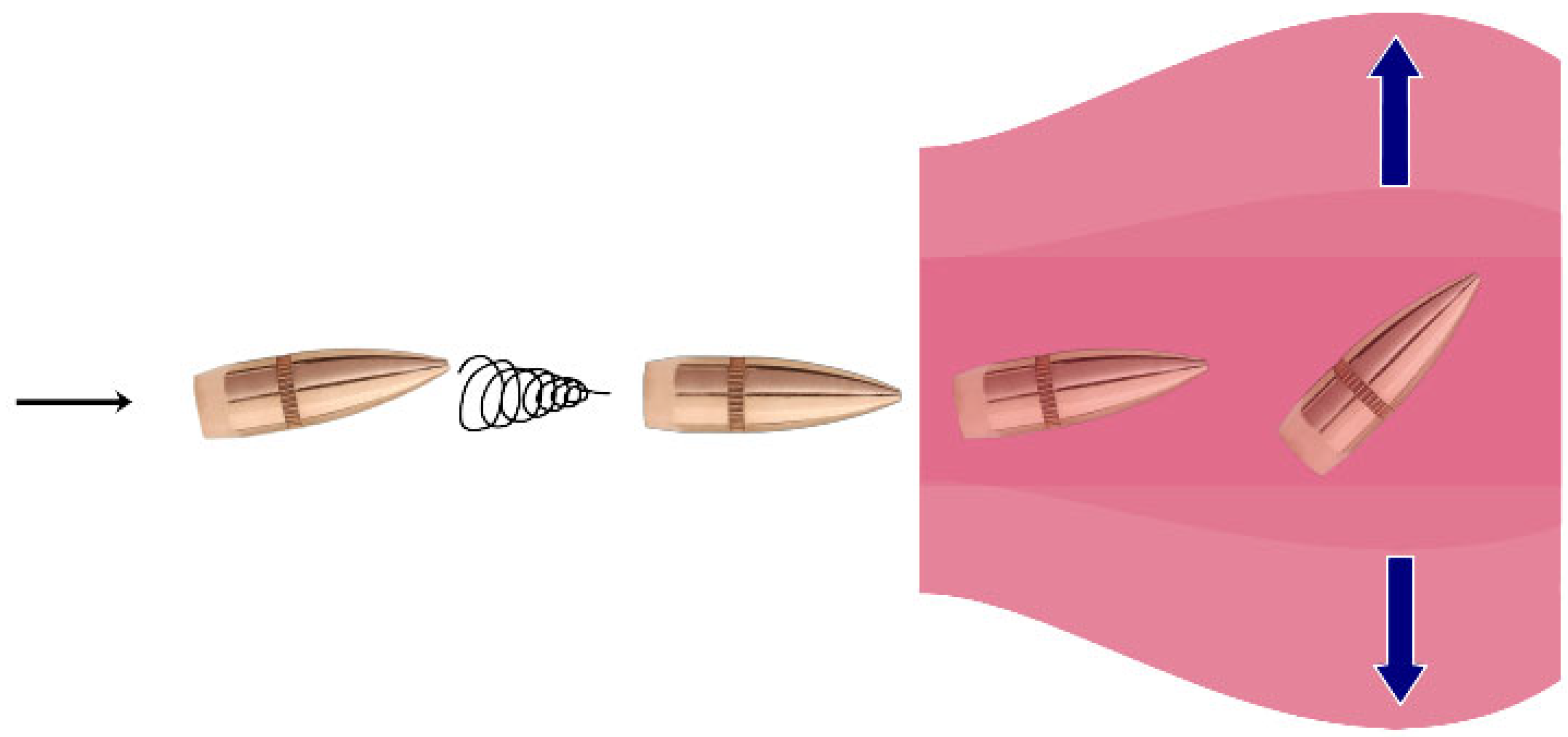

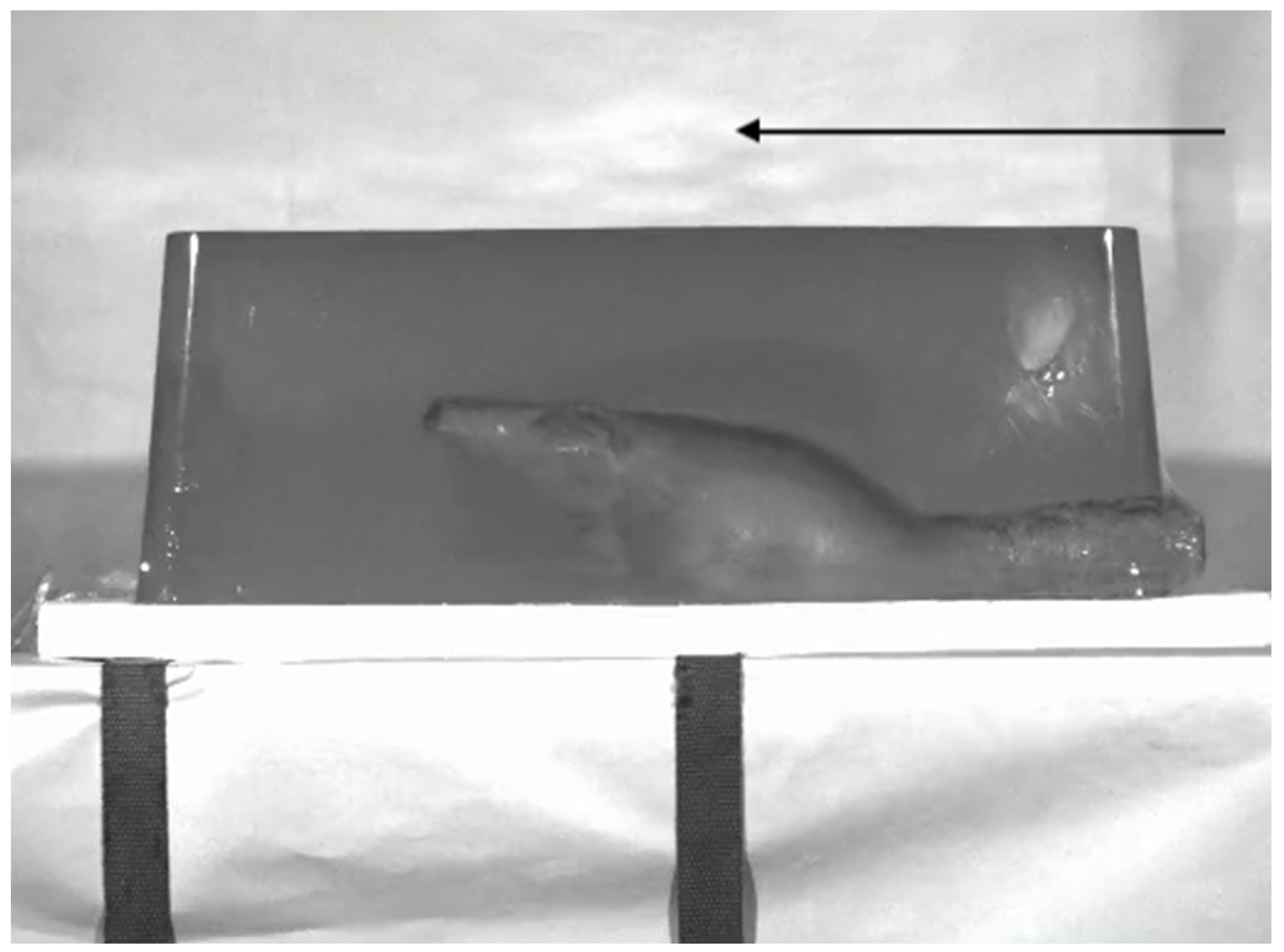

2.2. Pathophysiology of Bullet Wounds and Cavitation Injuries

2.3. High Energy Injuries

2.4. Shotgun Injuries

2.5. Bone Injuries

2.6. Infectious Potential of Gunshot Wounds

3. Initial Evaluation of Gunshot Injuries

3.1. General Principles

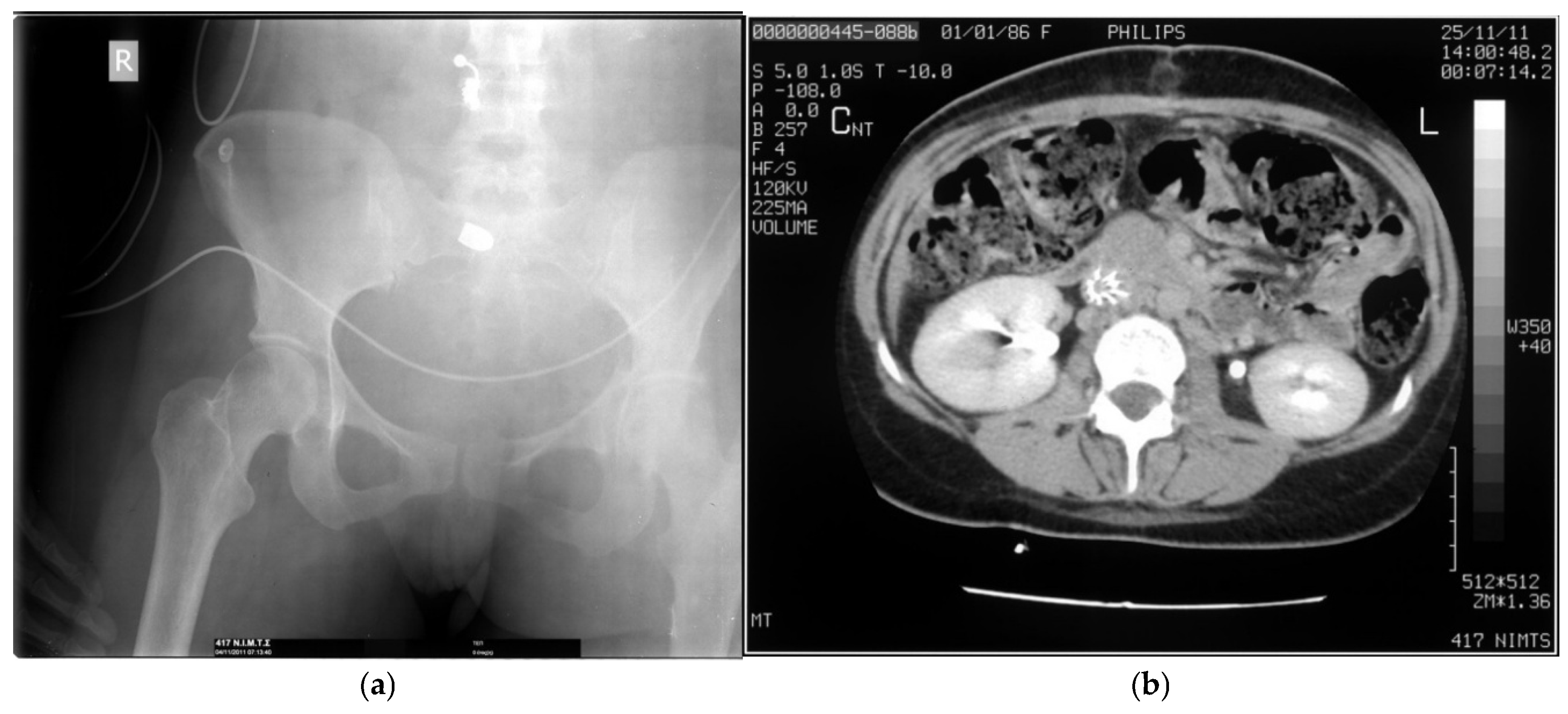

3.2. Trajectory Analysis and Imaging

3.3. Vascular Injury of the Extremities

3.4. Debridement of Soft Tissue Gunshot Wounds

3.5. Removal of Retained Projectiles

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Firearm Violence in the United States. Available online: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/center-for-gun-violence-solutions/research-reports/gun-violence-in-the-united-states#:~:text=Evidence%20consistently%20shows%20that%20access%20to%20firearms%20increases%20the%20risk%20of%20suicide.&text=Access%20to%20a%20firearm%20in,suicide%20more%20than%20three%2Dfold.&text=Firearms%20are%20dangerous%20when%20someone,most%20lethal%20suicide%20attempt%20method (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fast Facts: Firearm Injury and Death. July 5, 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/firearm-violence/data-research/facts-stats/index.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Rozenfeld, M.; Givon, A.; Rivkind, A.; Bala, M.; Peleg, K.; Israeli Trauma Group (ITG). New trends in terrorism-related injury mechanisms: Is there a difference in injury severity? Ann Emerg Med 2019, 74, 697–705. [CrossRef]

- Binkley, J.M.; Kemp, K.M. Mobilization of resources and emergency response on the national scale. Surg Clin North Am 2022, 102, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Ditkofsky, N.; Nair, J.R.; Frank, Y.; Mathur, S.; Nanda, B.; Moreland, R.; Rotman, J.A. Understanding ballistic injuries. Radiol Clin North Am 2023, 61, 119–128. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Correia, M. Surgical frontiers in war zones: perspectives and challenges of a humanitarian surgeon in conflict environments. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2024, 9, e001234. [CrossRef]

- Baum, G.R.; Baum, J.T.; Hayward, D.; MacKay, B.J. Gunshot wounds: ballistics, pathology, and treatment recommendations, with a focus on retained bullets. Orthop Res Rev 2022, 14, 293–317. [CrossRef]

- Karger, B. Forensic ballistics: injuries from gunshots, explosives and arrows. In Handbook of Forensic Medicine, 2nd ed.; Madea, B., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 459–503. [CrossRef]

- Dries, D.J. Guns, bullets, and wounds. Air Med J 2023, 42, 80–85. [CrossRef]

- Stefanopoulos, P.K.; Tsiatis, N.E.; Herbstein, J.A. Gunshot wounds. In Encyclopedia of Forensic Sciences, 3rd ed.; Houck, M.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2023, Volume 3, pp. 75–98. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.M.P.; da Cunha, M.R.; Reis C.H.B.; Buchaim, D.V.; da Rosa, A.P.B.; Tempest, L.M.; da Cruz, J.A.P.; Buchaim, R.L.; Issa, J.P.M. The use of human surrogates in anatomical modeling for gunshot wounds simulations: an overview about “how to do” experimental terminal ballistics. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2025, 13, 1536423. [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, B.D. Gunshot wounds: a historical perspective. Mil Med 1984, 149, 301–315. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, C.; Monier, B.; Wright, M.; Lesiak, A. Gunshot wounds to the extremity. In Encyclopedia of Trauma Care; Papadakos, P.J., Gestring, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 703–707. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, P.M.; Moore, E.E.; Joseph, B.; Tang, A.; Pandit, V.; Vercruysse, G. Gunshot wounds: A review of ballistics, bullets, weapons, and myths. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016, 80, 853–867. [CrossRef]

- DeMuth, W.E., Jr. Bullet velocity and design as determinants of wounding capability: an experimental study. J Trauma 1966, 6, 222–232.

- Bruner, D.; Gustafson, C.G.; Visintainer, C. Ballistic injuries in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract 2011, 13, 1–32.

- Ommundsen, H.; Robinson, E.H. Rifles and Ammunition; Cassell: London, UK, 1915; Chapter 10: Sporting Rifle Ammunition, pp. 179–185.

- DiMaio, V.J.M. Gunshot Wounds: Practical Aspects of Firearms, Ballistics, and Forensic Techniques, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016, ISBN 978-1-4987-2569-9.

- Kneubuehl, B.P. Wound ballistics and international agreements. In Wound Ballistics: Basics and Applications, 2nd ed.; Kneubuehl, B.P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 337–358. [CrossRef]

- Anatoliyovych, I.L.; Yuriyovych, O.U.; Valentynovych, O.H. Surgical treatment features of liver gunshot wound with a dumdum bullet (expanding bullet). Int J Emerg Med 2022, 15, 57. [CrossRef]

- Gumeniuk, K.; Lurin, I.A.; Tsema, I.; Malynovska, L.; Gorobeiko, M.; Dinets, A. Gunshot injury to the colon by expanding bullets in combat patients wounded in hybrid period of the Russian-Ukrainian war during 2014-2020. BMC Surg 2023, 23, 23. [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, B.E. Mechanism of injury. In Bledsoe’s Paramedic Care: Principles & Practice, 6th ed.; Bledsoe, B.E., Porter, R.S., Cherry, R.A., Eds.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 1757–1793, ISBN 978-013-691459-4.

- Walker, J. Halliday & Resnick Fundamentals of Physics, 12th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 1, Chapter 7: Kinetic energy and work, pp. 156–185, ISBN 978-1-119-80115-3.

- McAninch, J.W.; Santucci, R.A. Renal and ureteral trauma. In Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th ed.; Kavoussi, L.R.; Novick, A.C.; Partin, A.W.; Peters, C.A., Eds.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 1274–1292, ISBN 978-0-7216-0798-5.

- Burkhalter, W.E. Orthopedic Surgery in Vietnam; Office of the Surgeon General: Washington DC, USA, 1994.

- Fackler, M.L. Wound ballistics. A review of common misconceptions. JAMA 1988, 259, 2730–2736. [CrossRef]

- Hollerman, J.J.; Fackler, M.L. Wound ballistics. In Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7th ed.; Tintinalli J.E., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. e38–e43, ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- Mendelson, J.A. The relationship between mechanisms of wounding and principles of treatment of missile wounds. J Trauma 1991, 31, 1181–1202. [CrossRef]

- Owen-Smith, M.S. High-velocity and military gunshot wounds. In Management of Gunshot Wounds; Ordog, G.J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 61–94, ISBN 0-444-01246-X.

- Kneubuehl, B.P. General wound ballistics. In Wound Ballistics: Basics and Applications, 2nd ed.; Kneubuehl, B.P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 87–163. [CrossRef]

- Kneubuehl, B.P. Ballistics: Theory and Practice (Translated from the German language edition by Rawcliffe, S.); Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Chapter 2: Physical basics, p. 34. [CrossRef]

- Janzon, B. Projectile-material interactions: simulants. In Scientific Foundations of Trauma; Cooper, G.J., Dudley, H.A.F., Gann, D.S., Little, R.A., Maynard, R.L., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 26–36, ISBN 0 7506 1585 0.

- Fackler, M.L.; Surinchak, J.S.; Malinowski, J.A.; Bowen, R.E. Bullet fragmentation: a major cause of tissue disruption. J Trauma 1984,24, 35-39.

- Berlin, R.H.; Janzon, B.; Lidén, E.; Nordström, G.; Schantz, B.; Seeman, T.; Westling, F. Terminal behaviour of deforming bullets. J Trauma 1988, 28, S58-S62. [CrossRef]

- Fackler, M.L. Wounding patterns of military rifle bullets. Int Defense Rev 1989, 22, 159–165.

- Stefanopoulos, P.K.; Mikros, G.; Pinialidis, D.E.; Oikonomakis, I.N.; Tsiatis, N.E.; Janzon, B. Wound ballistics of military rifle bullets: An update on controversial issues and associated misconceptions. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019, 87, 690–698. [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, D. Bullet Penetration: Modelling the Dynamics and the Incapacitation Resulting from Wound Trauma; Ballistic publications: El Segundo, CA, USA, 2005; Chapter 4: Incapacitation of bullet wounds, p. 52, ISBN 0-9643577-1-2.

- Reginelli, A.; Russo, A.; Maresca, D.; Martiniello, C.; Cappabianca, S.; Brunese, L. Imaging assessment of gunshot wounds. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2015, 36, 57–57. [CrossRef]

- Altheimer, I.; Schaible, L.M.; Klofas, J.; Comeau, M. Victim characteristics, situational factors, and the lethality of urban gun violence. J Interpers Violence 2019,34, 1633-1656. [CrossRef]

- Moritz, A.R. The Pathology of Trauma, 2nd ed.; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, USA, 1954; p. 64.

- Riddez, L. Wounds of war in the civilian sector: principles of treatment and pitfalls to avoid. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2014, 40, 461–468. [CrossRef]

- Ordog, G.J.; Prakash, A. Civilian gunshot wounds: determinants of injury. In Management of Gunshot Wounds; Ordog, G.J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 157–165, ISBN 0-444-01246-X.

- Braga, A.A.; Cook, P.J. The association of firearm caliber with likelihood of death from gunshot injury in criminal assaults. JAMA Netw Open 2018, 1, e180833. [CrossRef]

- Tracqui, A.; Deguette, C., Delabarde, T.; Delannoy, Y.; Plu, I; Sec, I.; Hamza, L.; Taccoen, M.; Ludes, B. An overview of forensic operations performed following the terrorist attacks on November 13, 2015, in Paris. Forensic Sci Res 2020, 5, 202–207. [CrossRef]

- Spitz, W.U.; Diaz, F.J. Spitz and Fisher’s Medicolegal investigation of Death: Guidelines for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigation, 5th ed.; Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL, USA, 2020; Chapter 8: Injury by gunfire, pp. 313–403, ISBN 9780398093129.

- Witzenhausen, M.; Brill, S.; Schmidt, R.; Beltzer, C. Aktuelle Mortalität von Kriegsverletzungen—eine narrative Übersichtsarbeit. Chirurgie, 2024, 95, 546–554. [CrossRef]

- DeMuth, W.E., Jr.; Smith, J.M. High-velocity bullet wounds of muscle and bone: the basis of rational early treatment. J Trauma 1966, 6, 744–755. [CrossRef]

- Amato, J.L.; Billy, L.J.; Lawson, N.S.; Rich, N.M. High velocity missile injury. An experimental study of the retentive forces of tissue. Am J Surg 1974, 127, 454–459. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Xu, C.; Jin, Y.; Batra, R.C. Rifle bullet penetration into ballistic gelatin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2017, 67, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Stefanopoulos, P.K.; Koutsouvela, D.G.; Panagiotopoulou, O.; Herbstein, J.; Tsiatis, N.; Mikros, G.; Pinialidis, D.E.; Salemis, N.S. Biomechanics of gunshot injuries and applications to wound ballistics research. In Forensic Analysis of Gunshot Residue, 3D-Printed Firearms, and Gunshot Injuries: Current Research and Future Perspectives; Cizdziel, J., Black, O., Eds.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 121–165, ISBN 978-1-53614-882-4.

- Fackler, M.L.; Surinchak, J.S.; Malinowski, J.A.; Bowen, R.E. Wounding potential of the Russian AK-74 assault rifle. J Trauma 1984, 24, 263–266. [CrossRef]

- Khandar, S.J.; Johnson, S.B.; Calhoon, J.H. Overview of thoracic trauma in the United States. Thorac Surg Clin 2007, 17, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Karademir, K.; Gunhan, M.; Can, C. Effects of blast injury on kidneys in abdominal gunshot wounds. Urology 2006, 68, 1160–1163. [CrossRef]

- Owers, C.; Garner, J. Intra-abdominal injury from extra-peritoneal ballistic trauma. Injury, 2014, 45, 655–658. [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.F.; Nahass, M.M.; Iacono, S.A.; Grover, K.; Shan, Y.; Ferraro, J.; Ikegami, H.; Hanna, J.S. Delayed cardiac tamponade secondary to blast injury from gunshot wound. Trauma Case Rep 2023, 47, 100914. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yoganandan, N.; Pintar, F.A.; Gennarelli, T.A. Temporal cavity and pressure distribution in a brain simulant following ballistic penetration. J Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 1335–1347. [CrossRef]

- Oehmichen, M.; Meissner, C.; König, H.G.; Gehl, H.B. Gunshot injuries to the head and brain caused by low-velocity handguns and rifles: A review. Forensic Sci Int 2004, 146, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Janzon, B.; Hull, J.B.; Ryan, J.M. Projectile-material interactions: soft tissue and bone. In Scientific Foundations of Trauma; Cooper, G.J., Dudley, H.A.F., Gann, D.S., Little, R.A., Maynard, R.L., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 37–52, ISBN 0 7506 1585 0.

- Myerson, M.S.; Sammarco, V.J. Penetrating and lacerating injuries of the foot. Foot Ankle Clin 1999, 4, 647–672.

- Shin, E.H.; Sabino, J.M.; Nanos, G.P., III; Valerio, I.L. Ballistic trauma: Lessons learned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Semin Plast Surg 2015, 29, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Adams M.H.; Gaviria, M.; Sabbag, C.M. Military ballistic injuries of the upper extremity. Hand Clin 2025, 41, 269–280. [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, B.; Berlin, R.; Janzon, B.; Nordström, G.; Nylöf, U.; Rybeck, B.; Schantz, B.; Seeman, T. The extent of muscle tissue damage following missile trauma one six and twelve hours after the infliction of trauma, studied by the current method of debridement. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1979, 489, 137–144.

- Wang, Z.G.; Feng, J.X.; Liu, Y.Q. Pathomorphological observations of gunshot wounds. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1982, 508, 185–195.

- Fackler, M.L.; Breteau, J.P.; Courbil, L.J.; Taxit, R.; Glas, J.; Fievet, J.P. Open wound drainage versus wound excision in treating the modern assault rifle wound. Surgery 1989, 105, 576–584.

- Popov, V.A.; Vorob’ev, V.V.; Pitenin, I.Y. Microcirculatory changes in tissues surrounding a gunshot wounds. Bull Exp Biol Med 1990, 109, 437–441. [CrossRef]

- Vuong, P.N.; Berry, C. The Pathology of Vessels; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002; Chapter 6: Vascular trauma, pp. 119–137. [CrossRef]

- Le Gros Clark, W.E.; Blomfield, L.B. The efficiency of intramuscular anastomoses, with observations on the regeneration of devascularized muscle. J Anat 1945, 79, 15–32.

- Grosse Perdekamp, M.; Kneubuehl, B.P.; Serr, A.; Vennemann, B.; Pollak, S. Gunshot-related transport of micro-organisms from the skin of the entrance region into the bullet path. Int J Legal Med 2006, 120, 257–264. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.B.; Tai, N.R.M.; Martin, M.J. Military vascular injuries; considerations and techniques. In Vascular Injury: Endovascular and Open Surgical Management; DuBose, J.J.; Teixeira, P.G., Rajani, R.R., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 273–284. ISBN 978-1-26-426983-9.

- Ragsdale, B.D.; Josselson, A. Experimental gunshot fractures. J Trauma 1988, 28, S109–S115. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Qian, C.W.; Zhan, D.C.; Shi, T.Z.; Tang, C.G. Pathological changes of gunshot wounds at various intervals after wounding. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1982, 508, 197–210.

- Penn-Barwell, J.G.; Sargeant, I.D.; Severe Lower Extremity Combat Trauma (SeLECT) Study Group. Gun-shot injuries in UK military casualties—Features associated with wound severity. Injury 2016, 47, 1067–1071. [CrossRef]

- Manta, A.M.; Petrasso, P.E.Y.; Tomassini, L.; Piras, G.N.; De Maio, A.; Cappelletti, S.; Straccamore, M.; Siodambro, C.; De Simone, S.; Peonim, V.; et al. The wounding potential of assault rifles: analysis of the dimensions of entrance and exit wounds and comparison with conventional handguns. A multicentric study. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2024, 20, 896–909. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J.J.; Naess, P.A.; Gaarder, C. Injuries caused by fragmenting rifle ammunition. Injury 2016, 47, 1951–1954. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.J.; McKenna, K.D. Sander’s Paramedic Textbook, 6th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2025; ISBN 9781284264791.

- Ng, E.; Choong, A.M.T.L. External iliac artery injury secondary to indirect pressure wave effect from gunshot wound. Chin J Traumatol 2016, 19, 134–135. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.D.; Ketterer, A.R. Gunshot attacks: mass casualties. In Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine, 3rd ed.; Ciottone, G.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 904–906. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.E.; Stannard, A. Injury to extremities. In Fischer’s Mastery of Surgery, 6th ed.; Fischer, J.E., Ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 2495–2504, ISBN 978-1-60831-740-0.

- White, J.M.; Stannard, A.; Burkhardt, G.E.; Eastridge, B.J.; Blackbourne, L.H.; Rasmussen, T.E. The epidemiology of vascular injury in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Ann Surg 2011, 25, 1184–1189. [CrossRef]

- Tarkunde, Y.R.; Clohisy, C.J.; Calfee, R.P.; Halverson, S.J.; Wall, L.B. Firearm injuries to the wrist and hand in children and adults: an epidemiologic study. Hand (N Y) 2023,18, 575-581. [CrossRef]

- Rich, N.M.; Spencer, F.C. Vascular Trauma; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1978; Chapter 3: Experimental arterial trauma, pp. 44–60, ISBN 0-7216-7580-8.

- Straszewski, A.J.; Schultz, K.; Dickherber, J.L.; Dahm, J.S.; Wolf, J.M.; Strelzow, J.A. Gunshot-related upper extremity nerve injuries at a level 1 trauma center. J Hand Surg Am 2022, 47, 88.e1-88.e6. [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, T.J., 3rd; Zelenski, N.A. Ballistic injuries of the brachial plexus. Hand Clin 2025, 41, 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Otten, E.J. Hunting and fishing injuries. In Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th ed.; Auerbach, P.S., Cushing, T.A.; Harris, N.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 549–563, ISBN 978-0-323-35942-9.

- Schmidt, A.; Wise, K.; Kelly, B. The physics of trauma. In PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 10th ed.; Pollak, A.N., Ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 103–147, ISBN 9781284264746.

- Glezer, J.A.; Minard, G.; Croce, M.A.; Fabian, T.C.; Kudsk, K.A. Shotgun wounds to the abdomen. Am Surg 1993, 59, 129–132.

- Cestero, R.; Plurad, D.; Demetriades, D. Ballistics. In Color Atlas of Emergency Trauma, 3rd ed.; Demetriades, D., Chudnofsky C.R., Benjamin, E.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Breitenecker, R. Shotgun wound patterns. Am J Clin Pathol 1969, 52, 258–269. [CrossRef]

- Gestring, M.L.; Geller, E.R.; Akkad, N.; Bongiovanni, P.J. Shotgun slug injuries: case report and literature review. J Trauma 1996, 40, 650–653. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Saif, T.; Presley, BR.; Yang, K.H. The mechanical behaviour of biological tissues at high strain rates. In Military Injury Biomechanics: The Cause and Prevention of impact Injuries; Franklyn, M., Vee Sin Lee, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 103–118, ISBN 978-1-4987-4282-5.

- Caister, A.J.; Carr, D.J.; Campbell, P.D.; Brock, F.; Breeze, J. The ballistic performance of bone when impacted by fragments. Int J Legal Med, 2020, 134, 1387–1393. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P. K.; Joshi, Y.K.; Ganpule, S.G. Review of interaction of bullets and fragments with skin-bone-muscle parenchyma. ASME J of Medical Diagnostics 2025, 8, 040801. [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.W.; Wheatley, K.K. Biomechanics of femur fractures secondary to gunshot wounds. J Trauma 1984, 24, 970–977. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.C.; Fujisaki, K.; Moore, E.E. Incomplete fractures associated with penetrating trauma: etiology, appearance and natural history. J Trauma 1988, 28, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, N.; Jordana, X.; Monreal, J.; Garrido, X.; Soler, J.; Vega, M.; Brillas, P.; Galtés, I. Ballistic long bone fracture pattern: an experimental study. Int J Legal Med 2024, 138, 1685–1700. [CrossRef]

- Harger, J.H.; Huelke, D.F. Femoral fractures produced by projectiles𑁋the effects of mass and diameter on target damage. J Biomech 1970, 3, 487–493. [CrossRef]

- Kieser, D.C.; Carr, D.J.; Leclair, S.C.J.; Horsfall, I.; Theis, J.C.; Swain, M.V.; Kieser, J.A. Gunshot induced indirect femoral fracture: mechanism of injury and fracture morphology. J R Army Med Corps 2013, 159, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.M.; Huang, M.J.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.G. Primary bacterial contamination of wound track. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1982, 508, 265–269.

- Hinz, B.J.; Muci-Küchler, K.H.; Smith, P.M. Distribution of bacterial in simplified surrogate extremities shot with small caliber projectiles. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE2013). Volume 3A: Biomedical and Biotechnology Engineering. San Diego, CA, USA, 15-21 November 2013; pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lazovic, R.; Radojevic, N.; Curovic, I. Performance of primary repair on colon injuries sustained from low- versus high-energy projectiles. J Forensic Leg Med 2016, 39, 125–129. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.C. Surgical infections in trauma. In Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed.; Gorbach, S.L.; Bartlett, J.G.; Blacklow, N.R., Eds.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; pp. 927–932, ISBN 0-7216-6119-X.

- Stewart, R.M. ATLS® Advanced Trauma Life Support® Student Course Manual, 10th ed.; American College of Surgeons: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018, ISBN 78-0-9968262-3-5.

- Lin, J.S.; Rhee, P.C. Wrist and forearm fractures from ballistic injuries. Hand Clin 2025, 41, 313–322. [CrossRef]

- Penn-Barwell, J.G.; Bennett, P.M.; Heil, K.M. Firearms, ballistics and gunshot wounds. In Trauma Care Manual, 3rd ed.; Greaves, I., Porter, K., Garner, J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 372–385. [CrossRef]

- Pilbery, R.; Lethbridge, K. Ambulance Care Practice, 2nd ed.; Class Professional Publishing: Bridgwater, Somerset, UK, 2023 (reprint); Chapter 17: Trauma, pp. 311–371, ISBN 9-781859-598542.

- Ferrada, P.; Duschesne, J.; Piehl, M. Prioritizing circulation over airway in trauma patients with exsanguinating injuries: What you need to know. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2025, online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Kuckelman, J.; Derickson, M.; Long, W.B.; Martin, M.J. MASCAL management from Baghdad to Boston: Top ten lessons learned from modern military and civilian MASCAL events. Curr Trauma Rep 2018, 4, 138–148. [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, P.; Dissanaike, S. Circulation first for the rapidly bleeding trauma patient𑁋It is time to reconsider the ABCs of trauma care. JAMA Surg 2023, 158, 884–885. [CrossRef]

- Gangidine, M.M.; Sorensen, D.M. Penetrating extremity trauma: Part I. Trauma Reports 2019, 20, 1–11.

- Martin, M.J.; Beekley, A.C.; Eckert, M.J. Front Line Surgery: A Practical Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Top Ten Combat Trauma Lessons, p. xxiii, ISBN 978-3-319-56780-8.

- Bohan, P.M.K.; Leonard, J.M.; Kaplan, L.J. A ‘Direct to operating room’ approach improves critically injured patient outcomes. Curr Opin Crit Care 2025, 31, online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.E.; Go, J.L.; Zee, C.-S. Radiographic assessment of cranial gunshot wounds. Neuroimaging Clin North Am 2002, 12, 229–248. [CrossRef]

- Offiah, C.; Twigg, S. Imaging assessment of penetrating craniocerebral and spinal trauma. Clin Radiol 2009, 64, 1146–1157. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.R. Gunshot wounds to the brain. In Head injury, 3rd ed.; Cooper, P.R., Ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1993; pp. 355–371, ISBN 0-683-02108-7.

- Rosenfeld, J.V.; Bell, R.S.; Armonda, R. Current concepts in penetrating and blast injury to the central nervous system. World J Surg 2015, 39, 1352–1362. [CrossRef]

- Dawoud, F.M.; Feldman, M.J.; Yengo-Kahn, A.M.; Roth, S.G.; Wolfson, D.I.; Ahluwalia, R.; Kelly, P.D.; Chitale, R.V. Traumatic cerebrovascular injuries associated with gunshot wounds to the head: a single-institution ten-year experience. World Neurosurg 2021, 146, e1031-e1044. [CrossRef]

- Boffard, K.D.; White, J.O. Manual of Definitive Surgical Trauma Care: Incorporating Definitive Anaesthetic Trauma Care, 6th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024, ISBN 9781032157818.

- Smith, E.R.; Sarani, B.; Shapiro, G.; Gondek, S.; Rivas, L.; Ju, T.; Robinson, B.Rh.; Estroff, J.M.; Fudenberg, J.; Amdur, R.; et al. Incidence and cause of potentially preventable death after civilian public mass shooting in the US. J Am Coll Surg 2019, 229, 244–251. [CrossRef]

- Pryor, J.P.; Reilly, P.M.; Dabrowski, G.P.; Grossman, M.D.; Schwab, C.W. Nonoperative management of abdominal gunshot wounds. Ann Emerg Med 2004, 43, 344–353. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, G. Abdominal trauma. In Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine, 5th ed.; Cameron, P., Little, M., Mitra, B., Deasy, C, Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 92–95, ISBN 978-0-7020-7624-4.

- Aylwin, C.; Jenkins, M. Abdominal aortic trauma, iliac and visceral vessel injuries. In Rich’s Vascular Trauma, 4th ed.; Rasmussen, T.E., Tai, N.R.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 212–225. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.K. Thoracic trauma. Ann Thorac Surg 1965, 1, 778–804. [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, I.; Tsema, I.; Humeniuk, K.; Makarov, H.; Rahushyn, D.; Yarynych, Y.; Sotnikov, A.; Slobodianyk, V.; Shypilov, S.; Dubenko, D.; et al. Application of damage control tactics and transpapillary biliary decompression for organ-preserving surgical management of liver injury in combat patient. Mil Med 2022, 187, e781-e786. [CrossRef]

- Persad, I.J.; Reddy, R.S.; Saunders, M.A.; Patel, J. Gunshot injuries to the extremities: experience of a U.K. trauma centre. Injury 2005, 36,407-411. [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, M.; Ferreira, N.; Birkholtz, F.F.; Graham, S.M.; Maqungo, S.; Held, M. Civilian gunshot injuries in orthopedics: a narrative review of ballistics, current concepts, and the South African experience. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021, 31, 923–930. [CrossRef]

- Sathiyakumar, V.; Thakore, R.V.; Stinner, D.J.; Obremskey, W.T.; Ficke, J.R.; Sethi, M.K. Gunshot-induced fractures of the extremities: a review of antibiotic and debridement practices. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015, 8, 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, A.M. Finding the missing bullet: A case report of an unusual trajectory from the left scapula into the left orbit. Trauma Case Rep 2021, 35, 100530. [CrossRef]

- Failla, A.V.M.; Licciardello, G.; Cocimano, G.; Di Mauro, L.; Chisari, M.; Sessa, F.; Salerno, M.; Esposito, M. Diagnostic challenges in uncommon firearm injury cases: a multidisciplinary approach. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 31. [CrossRef]

- Squire, L.F.; Novelline, R.A. Fundamentals of Radiology, 4th ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1988; Chapter 2: The invitation to think three-dimensionally, p. 17, ISBN 0-674-32926-0.

- Abbott, F.C. Surgery in the Græco-Turkish war. Lancet 1899, 153, 80–83. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L. The history of the use of the roentgen ray in warfare. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther 1945, 54, 649–672.

- Ledgerwood, A.M. The wandering bullet. Surg Clin North Am 1977, 57, 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, L.G.; Arce, C.A.; McKenzie, R.; Darmody, W.R.; Guyot, D.R.; Michael, D.B. Incidence of intracranial bullet fragment migration. Neurol Res 1999, 21, 475–480. [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Parsons, A.D.; Willis, S.; Moawad, S.A.; Zanzerkia, R.; Rahme, R. Sinking bullet syndrome: A unique case of transhemispheric migration. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2021, 204, 106607. [CrossRef]

- Aarabi, B.; Eisenberg, H. Surgical management and prognosis of penetrating brain injury. In Youmans & Winn Neurological Surgery, 8th ed.; Winn, H.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 3092–3104, ISBN 978-0-323-66192-8.

- Part2: Prognosis in penetrating brain injury (no authors listed). J Trauma 2001, 51(2 Suppl), S44-S86.

- Kothari, S.; Zhang, B.; Darji, N.; Woo, J. Prognosis after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A practical, evidence-based approach. In Brain injury Medicine: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; Zasler, N.D., Katz, D.I., Zafonte, R.D., Eds.; Demos Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 248–270. [CrossRef]

- Zakrison, T.L.; Essig, R.; Polcari, A.; McKinley, W.; Arnold, D.; Beyene, R.; Wilson, K.; Rogers, S., Jr.; Matthews, J.B.; Millis, J.M.; et al. Review paper on penetrating brain injury: Ethical quandaries in the trauma bay and beyond. Ann Surg 2023, 277, 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Nemzek, W.R.; Hecht, S.T.; Donald, P.J.; McFall, R.A.; Poirier, V.C. Prediction of major vascular injury in patients with gunshot wounds to the neck. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996, 17, 161–167.

- Bagheri, S.C.; Khan, H.A.; Bell, R.B. Penetrating neck injuries. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2008, 20, 393–414. [CrossRef]

- Majors, J.S.; Brennan, J.; Holt, G.R. Management of high-velocity injuries of the head and neck. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2017, 25, 493–502. [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.G. Approach to penetrating injuries of the neck. In Head, Face, and Neck Trauma: Comprehensive Management; Stewart, M.G., Ed.; Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 202–206, ISBN 1-58890-308-7.

- Bean, A.S. Trauma to the neck. In Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9th ed.; Tintinalli, J.E., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1722–1729, ISBN 978-1-260-01993-3.

- Evans, C.; Chaplin, T.; Zelt, D. Management of major vascular injuries: neck, extremities, and other things that bleed. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2018, 36, 181–202. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.Z.; Biffl, W.L. Thoracic trauma. In Textbook of Critical Care, 8th ed.; Vincent, J-L., Moore, F.A., Bellomo, R., Marini, J.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 1255–1263, ISBN 978-0-323-75929-8.

- Demetriades, D.; Benjamin, E.R. Emergency room resuscitative thoracotomy. In Color Atlas of Emergency Trauma, 3rd ed.; Demetriades, D., Chudnofsky C.R., Benjamin, E.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 328–334. [CrossRef]

- Clare, D.; Baxley, S. An evidence-based approach to managing gunshot wounds in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract 2023, 25, 1–28.

- Raja, A.S. Peripheral vascular trauma. In Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 10th ed.; Walls, R.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 429–437, ISBN 978-0-323-75847-5.

- Kauvar, D.S.; Sarfati, M.R.; Kraiss, L.W. National trauma databank analysis of mortality and limb loss in isolated lower extremity vascular trauma. J Vasc Surg 2011, 53, 1598–1603. [CrossRef]

- deSauza, I.S.; Benabbas, R.; McKee, S.; Zangbar, B.; Jain, A.; Paladino, L.; Boudourakis, L.; Sinert, R. Accuracy of physical examination, ankle-brachial index, and ultrasonography in the diagnosis of arterial injury in patients with penetrating extremity trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2017, 24, 994–1017. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, L.; Coimbra, R.; Goes, A.M.O., Jr.; Reva, V.; Santorelli, J.; Moore, E.; Galante, J.; Abu-Zidan, F.; Peitzman, A.B.; Ordonez, C.; et al. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma𑁋World Society of Emergency Surgery guidelines on diagnosis and management of peripheral vascular injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020, 89, 1183–1196. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.R.; Raja, A.S. Penetrating trauma to the extremities and vascular injuries. In Evidence-Based Emergency Care: Diagnostic Testing and Clinical Decision Rules, 3rd ed.; Pines, J.M., Bellolio, F., Carpenter, C.R., Raja, A.S., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2023; pp. 214–224. [CrossRef]

- Wahlgren, C.M.; Riddez, L. Penetrating arterial injuries below elbow/knee. In Penetrating Trauma: A Practical Guide on Operative Technique and Peri-Operative Management, 3 d ed.; Degiannis, E., Doll, D., Velmahos, G.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 635–640. [CrossRef]

- Colip, C.G.; Gorantla, V.; LeBedis, C.A.; Soto, J.A.; Anderson, S.W. Extremity CTA for penetrating trauma: 10-year experience using a 64-detector row CT scanner. Emerg Radiol 2017, 24, 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.V. Pittalls in the management of peripheral vascular injuries. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2017, 2, e000110. [CrossRef]

- Warwick, H.; Cherches, M.; Shaw, C.; Toogood, P. Comparison of computed tomography angiography and physical exam in the evaluation of arterial injury in extremity trauma. Injury 2021, 52, 1727–1731. [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, A.N.; DuBose, J.; Dua, A.; Betzold, R.; Bee, T.; Fabian, T.; Morrison, J.; Skarupa, D.; Podbielski, J.; Inaba, K.; et al. Hard signs gone soft: A croitical evaluation of presenting signs of extremity vascular injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021, 90, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kauvar, D.S., Propper, B.W. Lower extremity vascular trauma. In Rich’s Vascular Trauma, 4th ed.; Rasmussen, T.E., Tai, N.R.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 273–287. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, A.M. Traumatic proximal brachial artery injury selectively managed non-operatively: A case report and review of the literature. Trauma Case Rep 2022, 38, 100612. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, H.C.; Clasper, J.C.; Kay, A.R.; Parker, P.J.; Limb Trauma and Wounds Working Groups, ADMST. Initial extremity war wound debridement: a multidisciplinary consensus. J R Army Med Corps 2011, 157, 170–175. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, T.M.; Russo, C.J. Management of specific soft tissue injuries. In Reichman’s Emergency Medicine Procedures, 3rd ed.; Reichman, E.F., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1034–1049, ISBN 978-1-259-86192-5.

- Bowyer, M.W.; Rhee, P.; DuBose, J.J. Soft tissue wounds and fasciotomies. In Front Line Surgery: A Practical Approach, 2nd ed.; Martin, M.J., Beekley, A.C., Eckert, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 329–352, ISBN 978-3-319-56780-8.

- Stefanopoulos, P.K.; Aloizos, S.; Mikros, G.; Nikita, A.S.; Tsiatis, N.E.; Bissias, C.; Breglia, G.A., Janzon, B. Assault rifle injuries in civilians: ballistics of wound patterns, assessment and initial management. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2024, 50, 2741–2751. [CrossRef]

- Sassoon, A.; Riehl, J.; Rich, A.; Langford, J.; Haidukewych, G.; Pearl, G.; Koval, K.J. Muscle viability revisited: Are we removing normal muscle? A critical evaluation of dogmatic debridement. J Orthop Trauma 2016, 30, 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Schmalbruch, H. Skeletal Muscle. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985; Chapter: Development, regeneration, growth, p. 282. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).