Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Biological Characteristics of Breast Cancer

1.2. Genetic Risk Factors

1.3. Diagnosis and Progression

1.4. Metastasis and Disease Complexity

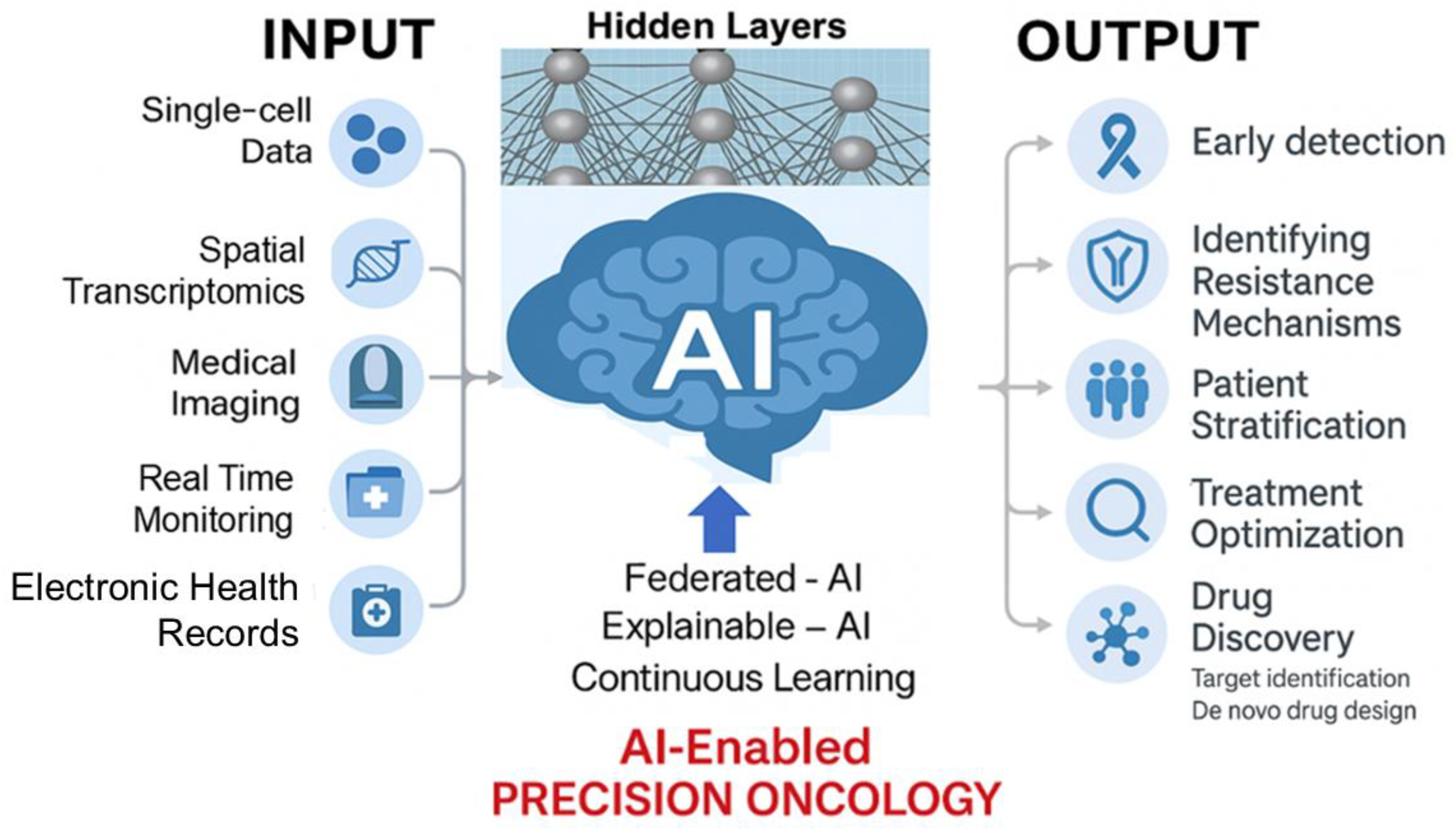

2. Early Detection and Diagnostic Technologies

3. Therapeutic Strategies and Ongoing Challenges

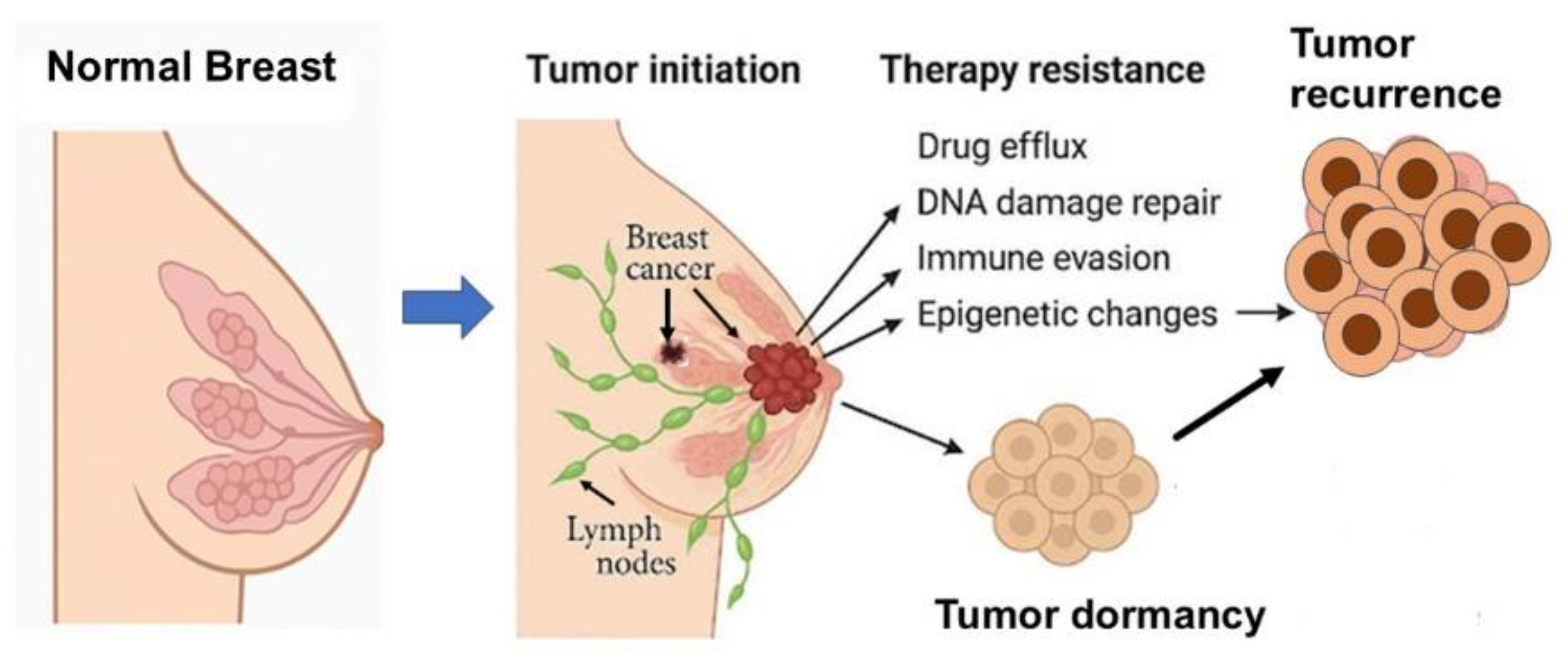

4. Resistance Mechanisms in Breast Cancer

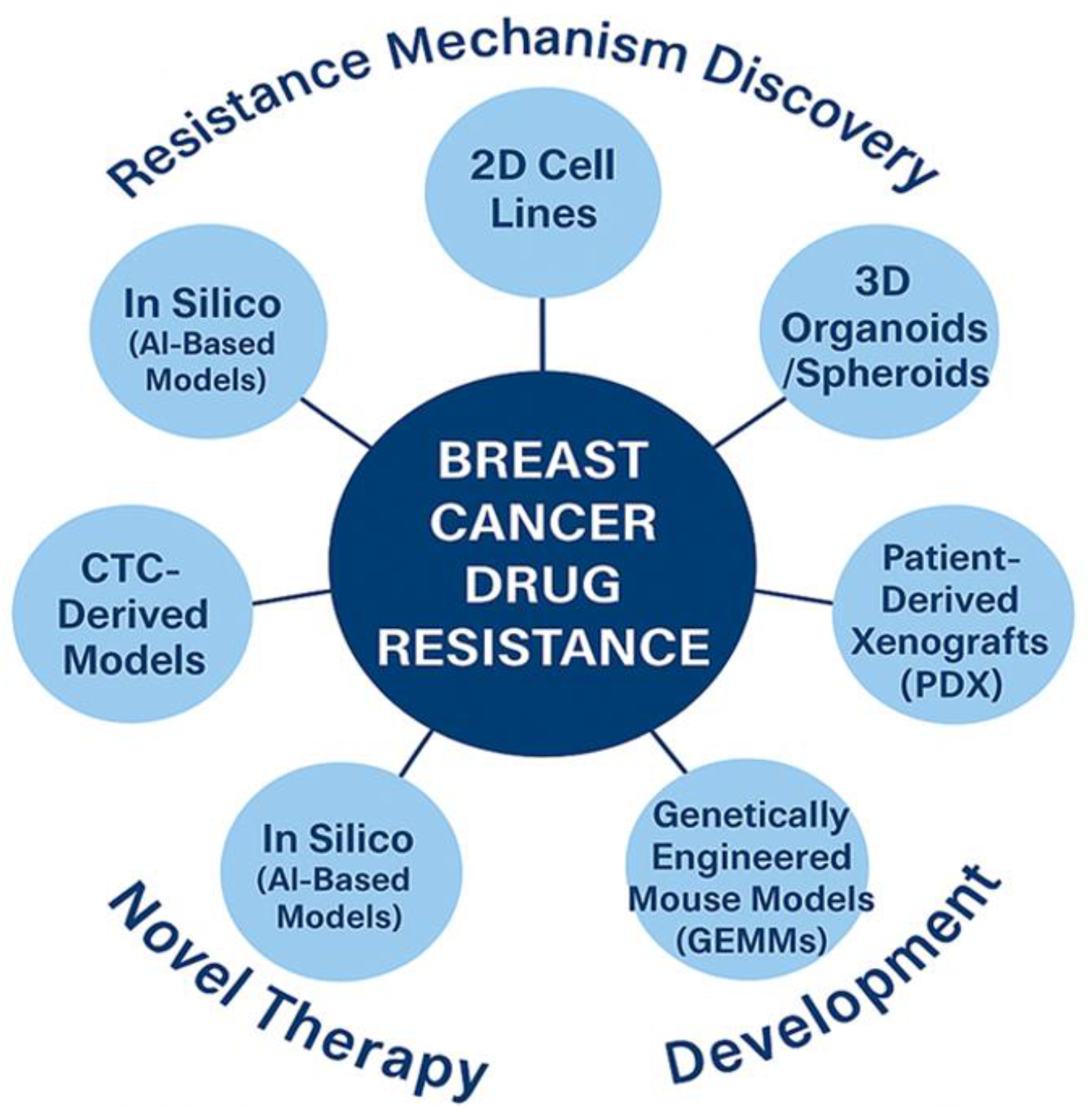

4.1. Experimental Models of Resistance Mechanisms

- i)

- ii)

- iii)

- iv)

- AI-based in silico models have facilitated target prediction and drug repurposing strategies, although biological validation remains a bottleneck [71].

4.2. Resistance Due to Drug Efflux

4.3. Resistance Due to Genetic Mutations

4.4. Molecular Signaling in Drug Resistance

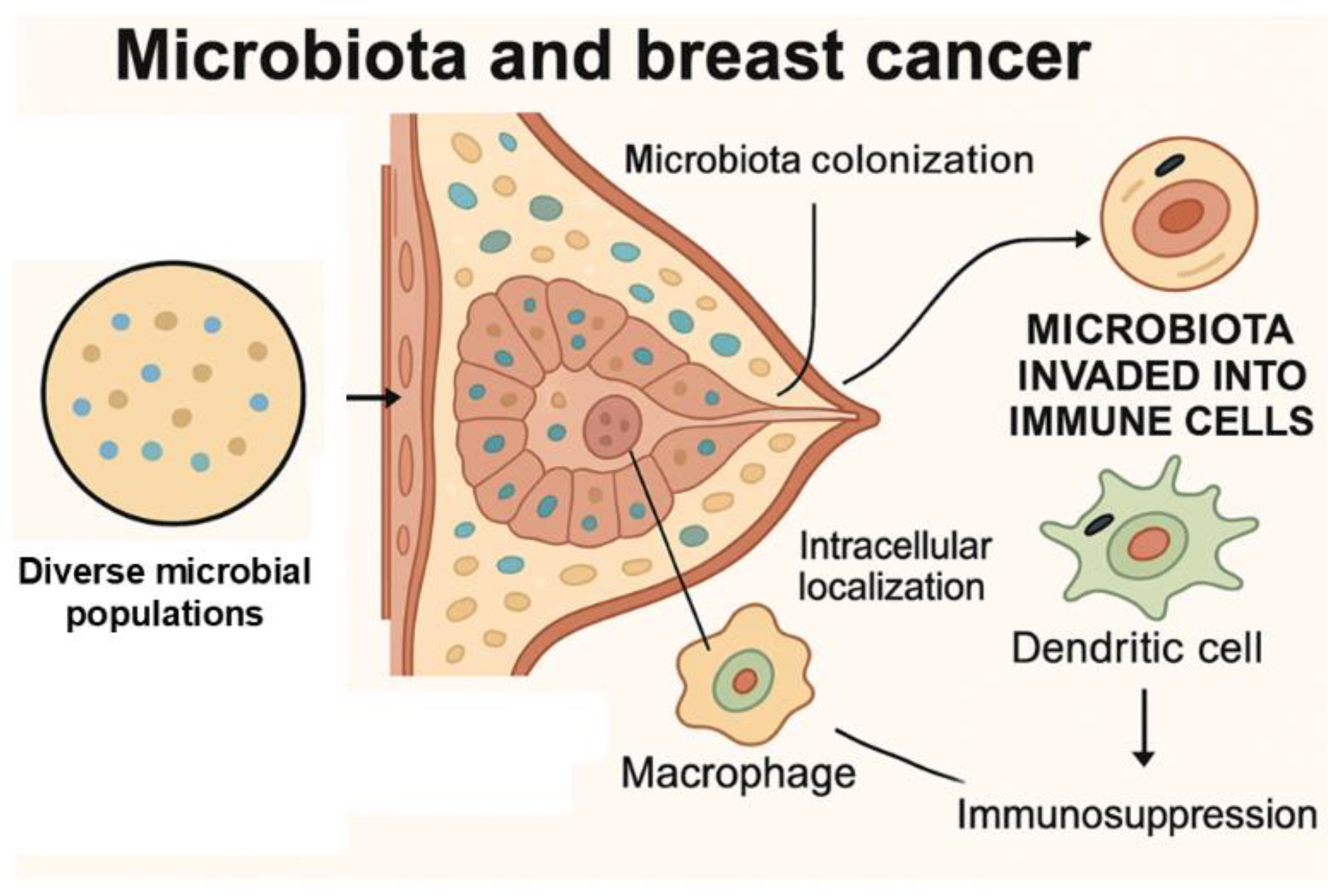

4.5. Role of Microbiota in Therapeutic Resistance

4.6. Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Resistance

4.7. Tumor Vasculature in Resistance

4.8. Role of Tumor Associated Macrophages in Immunosuppression

4.9. Role of Exosomes in TME Modulation

5. Metabolic Reprogramming in BC Resistance

5.1. Therapeutic Targeting of BC Metabolism

6. Breast Cancer Stem Cells (BCSCs) in Resistance

7. Role of Mitochondria in BC Resistance

7.1. Intercellular Mitochondrial Transfer

8. Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer

8.1. Immunometabolism and TME Modulation

8.2. Emerging Immunotherapies

9. Exosomes in Breast Cancer Resistance and Therapy

9.1. Role of MinPP1 in Carcinogenesis

10. Nanotechnology in Breast Cancer

10.1. Nanocarriers: Overcoming Cellular Resistance

11. Epigenetic Mechanisms Driving Resistance

12. Artificial Intelligence in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy

13. Personalized Medicine in Overcoming Resistance

14. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interests

References

- Harbeck, N., et al., Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2019. 5(1): p. 66.

- WHO, Breast Cancer. 2024.

- Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M., Morgan, E., Rumgay, H., Mafra, A., Singh, D., Laversanne, M., Vignat, J., Gralow, J. R., Cardoso, F., Siesling, S., & Soerjomataram, I. , Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. The Breast, 2022. 66: p. 15-23. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H., & Jemal, A., Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2025. 75(1): p. 4-35.

- Society, A.C., Cancer facts & figures 2025. 2025, Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

- Garrido-Castro, A.C., N.U. Lin, and K. Polyak, Insights into Molecular Classifications of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Improving Patient Selection for Treatment. Cancer Discov, 2019. 9(2): p. 176-198. [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I. and A.T. Shaw, Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018. 15(2): p. 81-94. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan D, W.R.A., Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 2011. 144(5): p. 646-674.

- Zheng, H.C., The molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancers. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(35): p. 59950-59964.

- Hanahan, D., Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov, 2022. 12(1): p. 31-46. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. and R.A. Weinberg, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 2011. 144(5): p. 646-74.

- Xiong, X., et al., Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2025. 10(1): p. 49.

- Dhiman, R., et al., Enhanced drug delivery with nanocarriers: a comprehensive review of recent advances in breast cancer detection and treatment. Discov Nano, 2024. 19(1): p. 143. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S., et al., Artificial Intelligence in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Personalized Medicine. J Breast Cancer, 2023. 26(5): p. 405-435. [CrossRef]

- Boire, A., et al., Why do patients with cancer die? Nat Rev Cancer, 2024. 24(8): p. 578-589.

- Makki, J., Diversity of Breast Carcinoma: Histological Subtypes and Clinical Relevance. Clin Med Insights Pathol, 2015. 8: p. 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Sinn, H.P. and H. Kreipe, A Brief Overview of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumors, 4th Edition, Focusing on Issues and Updates from the 3rd Edition. Breast Care (Basel), 2013. 8(2): p. 149-54. [CrossRef]

- Lukasiewicz, S., et al., Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated Review. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(17).

- Zubair, M., S. Wang, and N. Ali, Advanced Approaches to Breast Cancer Classification and Diagnosis. Front Pharmacol, 2020. 11: p. 632079. [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M., et al., Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 2000. 406(6797): p. 747-52. [CrossRef]

- Modi, S., et al., Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2022. 387(1): p. 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P., et al., Overall Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2024. 391(21): p. 1981-1991. [CrossRef]

- Waks, A.G. and E.P. Winer, Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA, 2019. 321(3): p. 288-300.

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B., et al., Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA, 2017. 317(23): p. 2402-2416.

- Antoniou, A.C., et al., Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371(6): p. 497-506. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., MRI Delta-Radiomics and Morphological Feature-Driven TabPFN Model for Preoperative Prediction of Lymphovascular Invasion in Invasive Breast Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat, 2025. 24: p. 15330338251362050. [CrossRef]

- Ehteshami Bejnordi, B., et al., Diagnostic Assessment of Deep Learning Algorithms for Detection of Lymph Node Metastases in Women With Breast Cancer. JAMA, 2017. 318(22): p. 2199-2210. [CrossRef]

- Le, E.P.V., et al., Artificial intelligence in breast imaging. Clin Radiol, 2019. 74(5): p. 357-366.

- Monje, M. and F. Winkler, Cancer research needs neuroscience and neuroscientists. Nat Neurosci, 2025. 28(5): p. 915-917. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E., D. Klubert, and D. Knutson, Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician, 2008. 78(12): p. 1361-6.

- Bianchini, G., et al., Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2016. 13(11): p. 674-690. [CrossRef]

- Nkondjock, A. and P. Ghadirian, [Risk factors and risk reduction of breast cancer]. Med Sci (Paris), 2005. 21(2): p. 175-80.

- Hoxha, I., et al., Breast Cancer and Lifestyle Factors: Umbrella Review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 2024. 38(1): p. 137-170.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast, C., Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol, 2012. 13(11): p. 1141-51.

- Kim, C., et al., Chemoresistance Evolution in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Delineated by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell, 2018. 173(4): p. 879-893 e13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. and M. Bahl, Assessing Risk of Breast Cancer: A Review of Risk Prediction Models. J Breast Imaging, 2021. 3(2): p. 144-155. [CrossRef]

- Almasi-Hashiani, A., et al., The causal effect and impact of reproductive factors on breast cancer using super learner and targeted maximum likelihood estimation: a case-control study in Fars Province, Iran. BMC Public Health, 2021. 21(1): p. 1219. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.E., et al., Benign Breast Disease and Breast Cancer Risk in the Percutaneous Biopsy Era. JAMA Surg, 2024. 159(2): p. 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.S., et al., Risk Factors and Preventions of Breast Cancer. Int J Biol Sci, 2017. 13(11): p. 1387-1397.

- Chlebowski, R.T., et al., Breast Cancer After Use of Estrogen Plus Progestin and Estrogen Alone: Analyses of Data From 2 Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol, 2015. 1(3): p. 296-305.

- Smith-Bindman, R., et al., Projected Lifetime Cancer Risks From Current Computed Tomography Imaging. JAMA Intern Med, 2025. 185(6): p. 710-719. [CrossRef]

- Hilakivi-Clarke, L., Maternal exposure to diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy and increased breast cancer risk in daughters. Breast Cancer Res, 2014. 16(2): p. 208. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.J.A., et al., Liquid Biopsy as a Tool for the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Monitoring of Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(17).

- Amato, O., N. Giannopoulou, and M. Ignatiadis, Circulating tumor DNA validity and potential uses in metastatic breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer, 2024. 10(1): p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Mashouri, L., et al., Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol Cancer, 2019. 18(1): p. 75. [CrossRef]

- Malla, R., et al., Exosome-Mediated Cellular Communication in the Tumor Microenvironment Imparts Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2025. 17(7). [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.L.L., et al., Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Global Breast Cancer Care: A Scoping Review of Applications, Outcomes, and Challenges. Cancers (Basel), 2025. 17(2). [CrossRef]

- Vatsavai, N., et al., Advances and challenges in cancer immunotherapy: mechanisms, clinical applications, and future directions. Front Pharmacol, 2025. 16: p. 1602529. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.Y., Z.M. Shao, and D.Q. Li, Tumor microenvironment: driving forces and potential therapeutic targets for breast cancer metastasis. Chin J Cancer, 2017. 36(1): p. 36. [CrossRef]

- Clough, K.B., et al., Improving breast cancer surgery: a classification and quadrant per quadrant atlas for oncoplastic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol, 2010. 17(5): p. 1375-91.

- Gentilini, O.D., et al., Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy vs No Axillary Surgery in Patients With Small Breast Cancer and Negative Results on Ultrasonography of Axillary Lymph Nodes: The SOUND Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2023. 9(11): p. 1557-1564.

- Hersh, E.H. and T.A. King, De-escalating axillary surgery in early-stage breast cancer. Breast, 2022. 62 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): p. S43-S49. [CrossRef]

- Burstein, H.J., et al., Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(5): p. 423-438. [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E., et al., Extending Aromatase-Inhibitor Adjuvant Therapy to 10 Years. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(3): p. 209-19. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P., et al., Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382(9): p. 810-821. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F., et al., 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol, 2020. 31(12): p. 1623-1649. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J., et al., Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2022. 387(3): p. 217-226. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M., et al., Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol, 2020. 21(4): p. 519-530. [CrossRef]

- Hortobagyi, G.N., et al., Ribociclib as First-Line Therapy for HR-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(18): p. 1738-1748. [CrossRef]

- Robson, M., et al., Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377(6): p. 523-533. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L., et al., Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin, 2025. 75(1): p. 10-45.

- Ibrahim, A., et al., Artificial intelligence in digital breast pathology: Techniques and applications. Breast, 2020. 49: p. 267-273. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A., N. Unni, and Y. Peng, The Changing Paradigm for the Treatment of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, D., et al., Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy. Circulation, 2015. 131(22): p. 1981-8. [CrossRef]

- Hadji, P., Aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss in breast cancer patients is distinct from postmenopausal osteoporosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2009. 69(1): p. 73-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Cancer stem cells and chemoresistance: The smartest survives the raid. Pharmacol Ther, 2016. 160: p. 145-58. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., et al., Advancing breast cancer research: a comprehensive review of in vitro and in vivo experimental models. Med Oncol, 2025. 42(8): p. 316. [CrossRef]

- Roarty, K. and G.V. Echeverria, Laboratory Models for Investigating Breast Cancer Therapy Resistance and Metastasis. Front Oncol, 2021. 11: p. 645698. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M., et al., Patient-derived xenograft models: an emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov, 2014. 4(9): p. 998-1013. [CrossRef]

- Chamorey, E., et al., Critical Appraisal and Future Challenges of Artificial Intelligence and Anticancer Drug Development. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2024. 17(7). [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M., S. McGarrigle, and G.P. Pidgeon, The next generation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway inhibitors in breast cancer cohorts. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2018. 1870(2): p. 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y., et al., In Vitro three-dimensional (3D) cell culture tools for spheroid and organoid models. SLAS Discov, 2023. 28(4): p. 119-137. [CrossRef]

- Nur Husna, S.M., et al., Inhibitors targeting CDK4/6, PARP and PI3K in breast cancer: a review. Ther Adv Med Oncol, 2018. 10: p. 1758835918808509. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M., et al., PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in breast cancer: research insights and sensitization strategies. Mol Cancer, 2024. 23(1): p. 266. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbluth, J.M., et al., Organoid cultures from normal and cancer-prone human breast tissues preserve complex epithelial lineages. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 1711. [CrossRef]

- Pedroza, D.A., et al., Leveraging preclinical models of metastatic breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2024. 1879(5): p. 189163. [CrossRef]

- Fina, E., et al., Gene signatures of circulating breast cancer cell models are a source of novel molecular determinants of metastasis and improve circulating tumor cell detection in patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2022. 41(1): p. 78. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., et al., Chemoresistance and Metastasis in Breast Cancer Molecular Mechanisms and Novel Clinical Strategies. Front Oncol, 2021. 11: p. 658552. [CrossRef]

- Moitra, K., H. Lou, and M. Dean, Multidrug efflux pumps and cancer stem cells: insights into multidrug resistance and therapeutic development. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2011. 89(4): p. 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Holohan, C., et al., Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer, 2013. 13(10): p. 714-26. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, M.M., T. Fojo, and S.E. Bates, Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer, 2002. 2(1): p. 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W., et al., Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2018. 18(7): p. 452-464. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S., et al., Managing Cancer Drug Resistance from the Perspective of Inflammation. J Oncol, 2022. 2022: p. 3426407. [CrossRef]

- Luo, B., et al., Cytochrome P450: Implications for human breast cancer. Oncol Lett, 2021. 22(1): p. 548. [CrossRef]

- Rizwanullah, M., et al., Receptor-Mediated Targeted Delivery of Surface-ModifiedNanomedicine in Breast Cancer: Recent Update and Challenges. Pharmaceutics, 2021. 13(12). [CrossRef]

- Bose, R., et al., Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov, 2013. 3(2): p. 224-37.

- Wang, Z.H., et al., Trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer: Mechanisms, emerging biomarkers and targeting agents. Front Oncol, 2022. 12: p. 1006429. [CrossRef]

- Harrod, A., et al., Genomic modelling of the ESR1 Y537S mutation for evaluating function and new therapeutic approaches for metastatic breast cancer. Oncogene, 2017. 36(16): p. 2286-2296. [CrossRef]

- Nahta, R., et al., Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol, 2006. 3(5): p. 269-80. [CrossRef]

- Menghi, F., et al., Genomic and epigenomic BRCA alterations predict adaptive resistance and response to platinum-based therapy in patients with triple-negative breast and ovarian carcinomas. Sci Transl Med, 2022. 14(652): p. eabn1926. [CrossRef]

- Tung, N. and J.E. Garber, PARP inhibition in breast cancer: progress made and future hopes. NPJ Breast Cancer, 2022. 8(1): p. 47. [CrossRef]

- Presti, D. and E. Quaquarini, The PI3K/AKT/mTOR and CDK4/6 Pathways in Endocrine Resistant HR+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer: Biological Mechanisms and New Treatments. Cancers (Basel), 2019. 11(9). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., J. Rauch, and W. Kolch, Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(3). [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, K.A. and V.L. Katanaev, The Signaling Duo CXCL12 and CXCR4: Chemokine Fuel for Breast Cancer Tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G., et al., Novel therapies emerging in oncology to target the TGF-beta pathway. J Hematol Oncol, 2021. 14(1): p. 55. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., et al., Prognostic correlations with the microbiome of breast cancer subtypes. Cell Death Dis, 2021. 12(9): p. 831. [CrossRef]

- Parhi, L., et al., Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 3259.

- Akinpelu, A., et al., The impact of tumor microenvironment: unraveling the role of physical cues in breast cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2024. 43(2): p. 823-844. [CrossRef]

- Deepak, K.G.K., et al., Tumor microenvironment: Challenges and opportunities in targeting metastasis of triple negative breast cancer. Pharmacol Res, 2020. 153: p. 104683. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. and L.M. Coussens, Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell, 2012. 21(3): p. 309-22. [CrossRef]

- Salemme, V., et al., The role of tumor microenvironment in drug resistance: emerging technologies to unravel breast cancer heterogeneity. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1170264. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. and H. Hao, The importance of cancer-associated fibroblasts in targeted therapies and drug resistance in breast cancer. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1333839. [CrossRef]

- Qian, K. and Q. Liu, Narrative review on the role of immunotherapy in early triple negative breast cancer: unveiling opportunities and overcoming challenges. Translational Breast Cancer Research, 2023. 4. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, F.J., et al., PTEN, PIK3CA, p-AKT, and p-p70S6K status: association with trastuzumab response and survival in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Am J Pathol, 2010. 177(4): p. 1647-56.

- Junttila, T.T., et al., Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer Cell, 2009. 15(5): p. 429-40. [CrossRef]

- Kinnel, B., et al., Targeted Therapy and Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2023. 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al., eNAMPT/Ac-STAT3/DIRAS2 Axis Promotes Development and Cancer Stemness in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Enhancing Cytokine Crosstalk Between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Cancer Cells. Int J Biol Sci, 2025. 21(5): p. 2027-2047.

- Zhi, S., et al., Hypoxia-inducible factor in breast cancer: role and target for breast cancer treatment. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1370800. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I., et al., Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Hypoxic Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 14(14).

- Chung, A.W., et al., Tocilizumab overcomes chemotherapy resistance in mesenchymal stem-like breast cancer by negating autocrine IL-1A induction of IL-6. NPJ Breast Cancer, 2022. 8(1): p. 30. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., et al., Targeting DCLK1 attenuates tumor stemness and evokes antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer by inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Breast Cancer Res, 2023. 25(1): p. 43.

- Novohradsky, V., et al., An anticancer Os(II) bathophenanthroline complex as a human breast cancer stem cell-selective, mammosphere potent agent that kills cells by necroptosis. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 13327. [CrossRef]

- Avancini, G., et al., Keratin nanoparticles and photodynamic therapy enhance the anticancer stem cells activity of salinomycin. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 2021. 122: p. 111899. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.B., et al., Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell, 2009. 138(4): p. 645-659. [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.W. and M.J. Naylor, Breast cancer stem cells. Front Physiol, 2013. 4: p. 225.

- Batlle, E. and H. Clevers, Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med, 2017. 23(10): p. 1124-1134. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Drug resistance and tumor immune microenvironment: An overview of current understandings (Review). Int J Oncol, 2024. 65(4). [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K., Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science, 2005. 307(5706): p. 58-62. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K., Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: from starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer Cell, 2014. 26(5): p. 605-22. [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D., et al., Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018. 15(5): p. 325-340. [CrossRef]

- Mou, J., et al., Research progress in tumor angiogenesis and drug resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med, 2024. 21(7): p. 571-85. [CrossRef]

- Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet, 1997. 350(9084): p. 1047-59.

- Gabrilovich, D.I., et al., Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med, 1996. 2(10): p. 1096-103. [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J. and M. Kurachi, Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol, 2015. 15(8): p. 486-99.

- Li, Y., et al., HIF-1alpha inhibitor YC-1 suppresses triple-negative breast cancer growth and angiogenesis by targeting PlGF/VEGFR1-induced macrophage polarization. Biomed Pharmacother, 2023. 161: p. 114423. [CrossRef]

- Juillerat, A., et al., An oxygen sensitive self-decision making engineered CAR T-cell. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 39833. [CrossRef]

- Supper, V.M., et al., Secretion of a VEGF-blocking scFv enhances CAR T-cell potency. Cancer Immunol Res, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., et al., Lack of acquired resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer cells after long-term HER2 siRNA nanoparticle treatment. PLoS One, 2018. 13(6): p. e0198141. [CrossRef]

- Brennen, W.N., et al., Overcoming stromal barriers to immuno-oncological responses via fibroblast activation protein-targeted therapy. Immunotherapy, 2021. 13(2): p. 155-175. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al., Efficacy and safety of camrelizumab combined with apatinib in advanced triple-negative breast cancer: an open-label phase II trial. J Immunother Cancer, 2020. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J., T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol, 2011. 12(6): p. 492-9.

- Xie, H., et al., CD8(+) T cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1507283. [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U., et al., Defining ’T cell exhaustion’. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019. 19(11): p. 665-674.

- Zhu, M., et al., Silence of a dependence receptor CSF1R in colorectal cancer cells activates tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunother Cancer, 2022. 10(12). [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M., et al., Targeting monocyte chemotactic protein-1 synthesis with bindarit induces tumor regression in prostate and breast cancer animal models. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2012. 29(6): p. 585-601. [CrossRef]

- Khan, O., et al., TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nature, 2019. 571(7764): p. 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. and V.S. LeBleu, The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science, 2020. 367(6478).

- Dong, X., et al., Exosomes and breast cancer drug resistance. Cell Death Dis, 2020. 11(11): p. 987. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., Exosome-mediated transfer of long noncoding RNA H19 induces doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol, 2020. 235(10): p. 6896-6904. [CrossRef]

- Saha, T., et al., Intercellular nanotubes mediate mitochondrial trafficking between cancer and immune cells. Nat Nanotechnol, 2022. 17(1): p. 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., et al., Metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic resistance in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Mol Cancer, 2024. 23(1): p. 261. [CrossRef]

- Alkarakooly, Z., et al., Metabolic reprogramming by Dichloroacetic acid potentiates photodynamic therapy of human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells. PLoS One, 2018. 13(10): p. e0206182. [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis, R.J. and N.S. Chandel, Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv, 2016. 2(5): p. e1600200.

- Hanahan, D., O. Michielin, and M.J. Pittet, Convergent inducers and effectors of T cell paralysis in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer, 2025. 25(1): p. 41-58. [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O., On the origin of cancer cells. Science, 1956. 123(3191): p. 309-14. [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, W.H., P.L. Bounds, and C.V. Dang, Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer, 2011. 11(5): p. 325-37.

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E., et al., Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017. 14(1): p. 11-31. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.M., et al., Metabolic strategies of melanoma cells: Mechanisms, interactions with the tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic implications. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res, 2018. 31(1): p. 11-30. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z., et al., Lactate oxidase nanocapsules boost T cell immunity and efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med, 2023. 15(717): p. eadd2712. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., et al., Cardamonin inhibits breast cancer growth by repressing HIF-1alpha-dependent metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019. 38(1): p. 377. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., et al., Metabolic Reprogramming Induces Immune Cell Dysfunction in the Tumor Microenvironment of Multiple Myeloma. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 591342. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M., et al., From metabolic byproduct to immune modulator: the role of lactate in tumor immune escape. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1492050. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.N., et al., Selective glutamine metabolism inhibition in tumor cells improves antitumor T lymphocyte activity in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Invest, 2021. 131(4). [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, J.B. and M.C. Haigis, The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol, 2018. 20(7): p. 745-754. [CrossRef]

- Ni, R., et al., Rethinking glutamine metabolism and the regulation of glutamine addiction by oncogenes in cancer. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1143798. [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.I., et al., Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther, 2014. 13(4): p. 890-901. [CrossRef]

- Lehuede, C., et al., Metabolic Plasticity as a Determinant of Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Cancer Res, 2016. 76(18): p. 5201-8. [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G. and R.J. DeBerardinis, Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell, 2017. 168(4): p. 657-669. [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, A., et al., Metabolic control of epigenetics in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2016. 16(11): p. 694-707. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S., J. Almagro, and E. Fuchs, Beyond genetics: driving cancer with the tumour microenvironment behind the wheel. Nat Rev Cancer, 2024. 24(4): p. 274-286. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P., et al., Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2022. 386(6): p. 556-567. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., M.A. Caligiuri, and J. Yu, Harnessing IL-15 signaling to potentiate NK cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol, 2022. 43(10): p. 833-847. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., Mechanisms and Strategies to Overcome PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Resistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 15(1).

- Bhola, N.E., et al., TGF-beta inhibition enhances chemotherapy action against triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Invest, 2013. 123(3): p. 1348-58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., et al., TGF-beta suppresses type 2 immunity to cancer. Nature, 2020. 587(7832): p. 115-120.

- Li, S., et al., Cancer immunotherapy via targeted TGF-beta signalling blockade in T(H) cells. Nature, 2020. 587(7832): p. 121-125.

- Georgoudaki, A.M., et al., Reprogramming Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Antibody Targeting Inhibits Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cell Rep, 2016. 15(9): p. 2000-11. [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L. and J.W. Pollard, Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2018. 17(12): p. 887-904. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M., et al., Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003. 100(7): p. 3983-8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., et al., Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem Cell Reports, 2014. 2(1): p. 78-91. [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, J.S. and L. Miele, Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Biomedicines, 2018. 6(3).

- Phi, L.T.H., et al., Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int, 2018. 2018: p. 5416923. [CrossRef]

- Plaks, V., N. Kong, and Z. Werb, The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell, 2015. 16(3): p. 225-38.

- Khoury, T., et al., Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 expression in breast cancer is associated with stage, triple negativity, and outcome to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Mod Pathol, 2012. 25(3): p. 388-97.

- Korkaya, H., S. Liu, and M.S. Wicha, Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Invest, 2011. 121(10): p. 3804-9.

- Ansieau, S., EMT in breast cancer stem cell generation. Cancer Lett, 2013. 338(1): p. 63-8. [CrossRef]

- Son, B., et al., Targeted therapy of cancer stem cells: inhibition of mTOR in pre-clinical and clinical research. Cell Death Dis, 2024. 15(9): p. 696. [CrossRef]

- Song, K. and M. Farzaneh, Signaling pathways governing breast cancer stem cells behavior. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2021. 12(1): p. 245. [CrossRef]

- Francescangeli, F., et al., Dormancy, stemness, and therapy resistance: interconnected players in cancer evolution. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2023. 42(1): p. 197-215. [CrossRef]

- Butti, R., et al., Breast cancer stem cells: Biology and therapeutic implications. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2019. 107: p. 38-52. [CrossRef]

- Palomeras, S., S. Ruiz-Martinez, and T. Puig, Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells to Overcome Treatment Resistance. Molecules, 2018. 23(9). [CrossRef]

- Gaude, E. and C. Frezza, Defects in mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cancer Metab, 2014. 2: p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Hekmatshoar, Y., et al., The role of metabolism and tunneling nanotube-mediated intercellular mitochondria exchange in cancer drug resistance. Biochem J, 2018. 475(14): p. 2305-2328. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K. and M. Kulawiec, Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and risk of cancer. Methods Mol Biol, 2009. 471: p. 291-303.

- Jimenez-Morales, S., et al., Overview of mitochondrial germline variants and mutations in human disease: Focus on breast cancer (Review). Int J Oncol, 2018. 53(3): p. 923-936. [CrossRef]

- Vikramdeo, K.S., et al., Profiling mitochondrial DNA mutations in tumors and circulating extracellular vesicles of triple-negative breast cancer patients for potential biomarker development. FASEB Bioadv, 2023. 5(10): p. 412-426. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reyes, I. and N.S. Chandel, Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 102. [CrossRef]

- Nahacka, Z., et al., Miro proteins and their role in mitochondrial transfer in cancer and beyond. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 937753. [CrossRef]

- Sotgia, F., M. Fiorillo, and M.P. Lisanti, Mitochondrial markers predict recurrence, metastasis and tamoxifen-resistance in breast cancer patients: Early detection of treatment failure with companion diagnostics. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(40): p. 68730-68745. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.B., Chinnery, P.F., , Extreme heterogeneity of human mitochondrial dNA from organelles to populations. Nat Rev Genet, 2021. 22: p. 106-118. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., et al., Mitochondrial signaling pathways and their role in cancer drug resistance. Cell Signal, 2024. 122: p. 111329.

- Delbridge, A.R., et al., Thirty years of BCL-2: translating cell death discoveries into novel cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer, 2016. 16(2): p. 99-109. [CrossRef]

- LeBleu, V.S., et al., PGC-1alpha mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol, 2014. 16(10): p. 992-1003, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., et al., Mitochondrial DNA methylation is a predictor of immunotherapy response and prognosis in breast cancer: scRNA-seq and bulk-seq data insights. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1219652. [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, J., et al., Preferential transfer of mitochondria from endothelial to cancer cells through tunneling nanotubes modulates chemoresistance. J Transl Med, 2013. 11: p. 94. [CrossRef]

- Patheja, P. and K. Sahu, Macrophage conditioned medium induced cellular network formation in MCF-7 cells through enhanced tunneling nanotube formation and tunneling nanotube mediated release of viable cytoplasmic fragments. Exp Cell Res, 2017. 355(2): p. 182-193. [CrossRef]

- Togashi, Y., K. Shitara, and H. Nishikawa, Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression - implications for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2019. 16(6): p. 356-371. [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, S., et al., Tunneling nanotubes, TNT, communicate glioblastoma with surrounding non-tumor astrocytes to adapt them to hypoxic and metabolic tumor conditions. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 14556. [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, L.X., et al., Mitochondrial Transfer in Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(6). [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. and J. Chen, Mitochondrial transfer - a novel promising approach for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2023. 14: p. 1346441. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S. and I. Mellman, Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity, 2013. 39(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.W., Y. Zhang, and R.A. Weinberg, Cell-intrinsic and microenvironmental determinants of metastatic colonization. Nat Cell Biol, 2024. 26(5): p. 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P., Role of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 in immunosuppression of breast cancer. Cancer Pathog Ther, 2024. 2(4): p. 246-255. [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A., Breast Cancer Immunotherapy: Facts and Hopes. Clin Cancer Res, 2018. 24(3): p. 511-520. [CrossRef]

- Setordzi, P., et al., The recent advances of PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for breast cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Pharmacol, 2021. 895: p. 173867. [CrossRef]

- Nihira, N.T., et al., Nuclear PD-L1 triggers tumour-associated inflammation upon DNA damage. EMBO Rep, 2025. 26(3): p. 635-655. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C., N. Joller, and V.K. Kuchroo, Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity, 2016. 44(5): p. 989-1004. [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, T.A., K.S. Chen, and K. Shah, Therapy-Induced Tumor Cell Death: Friend or Foe of Immunotherapy? Front Oncol, 2021. 11: p. 678562.

- Kalfeist, L., et al., Co-targeting TGF-beta and PD-L1 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer to experimental immunogenic cisplatin-eribulin chemotherapy doublet. J Clin Invest, 2025. 135(13). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Novel insight into the Warburg effect: Sweet temptation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2025. 214: p. 104844. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.W., et al., Blocking Tryptophan Catabolism Reduces Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Invasive Capacity. Cancer Res Commun, 2024. 4(10): p. 2699-2713. [CrossRef]

- Kundu, M., et al., Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and mechanism of immunotherapy-based drug resistance in breast cancer. Mol Cancer, 2024. 23(1): p. 92. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, A., et al., TGF-beta-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 4692. [CrossRef]

- Akinsipe, T., et al., Cellular interactions in tumor microenvironment during breast cancer progression: new frontiers and implications for novel therapeutics. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1302587. [CrossRef]

- Blass, E. and P.A. Ott, Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2021. 18(4): p. 215-229. [CrossRef]

- Jan, A., et al., An update on cancer stem cell survival pathways involved in chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Future Oncol, 2025. 21(6): p. 715-735.

- Stuber, T., et al., Inhibition of TGF-beta-receptor signaling augments the antitumor function of ROR1-specific CAR T-cells against triple-negative breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer, 2020. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H., Update of early phase clinical trials in cancer immunotherapy. BMB Rep, 2021. 54(1): p. 70-88. [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, S., et al., Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling. J Clin Immunol, 2012. 32(5): p. 1059-70. [CrossRef]

- Heater, N.K., S. Warrior, and J. Lu, Current and future immunotherapy for breast cancer. J Hematol Oncol, 2024. 17(1): p. 131. [CrossRef]

- Priceman, S.J., et al., Regional Delivery of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered T Cells Effectively Targets HER2(+) Breast Cancer Metastasis to the Brain. Clin Cancer Res, 2018. 24(1): p. 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, E.R., et al., Chimeric antigen receptor T cells secreting anti-PD-L1 antibodies more effectively regress renal cell carcinoma in a humanized mouse model. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(23): p. 34341-55. [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, L., et al., Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J Clin Invest, 2016. 126(8): p. 3130-44. [CrossRef]

- June, C.H., et al., CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science, 2018. 359(6382): p. 1361-1365.

- Kwon, Y., et al., Exosomal MicroRNAs as Mediators of Cellular Interactions Between Cancer Cells and Macrophages. Front Immunol, 2020. 11: p. 1167. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A., et al., The prognostic and therapeutic application of microRNAs in breast cancer: Tissue and circulating microRNAs. J Cell Physiol, 2018. 233(2): p. 774-786. [CrossRef]

- Ni, C., et al., Breast cancer-derived exosomes transmit lncRNA SNHG16 to induce CD73+gammadelta1 Treg cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020. 5(1): p. 41.

- Wang, Y., et al., The involvement and application potential of exosomes in breast cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1384946. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y., D. Baker, and P. Ten Dijke, TGF-beta-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(11). [CrossRef]

- Ruksha, T. and N. Palkina, Role of exosomes in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated cancer cell plasticity and drug resistance. Explor Target Antitumor Ther, 2025. 6: p. 1002322. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D., et al., Cancer-associated fibroblasts in breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2022. 42(5): p. 401-434. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J., et al., The role of PKM2 nuclear translocation in the constant activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis, 2021. 12(4): p. 291. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S., et al., CAF-derived exosomal LINC01711 promotes breast cancer progression by activating the miR-4510/NELFE axis and enhancing glycolysis. FASEB J, 2025. 39(7): p. e70471.

- Mortezaee, K., Exosomes in bridging macrophage-fibroblast polarity and cancer stemness. Med Oncol, 2025. 42(6): p. 216. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Z. Yan, and Y. Xia, [Silencing RAB27a inhibits proliferation, invasion and adhesion of triple-negative breast cancer cells]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao, 2023. 43(4): p. 560-567.

- O’Brien, K., et al., miR-134 in extracellular vesicles reduces triple-negative breast cancer aggression and increases drug sensitivity. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(32): p. 32774-89. [CrossRef]

- Halvaei, S., et al., Exosomes in Cancer Liquid Biopsy: A Focus on Breast Cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids, 2018. 10: p. 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, T., et al., Extracellular vesicle-mediated drug delivery in breast cancer theranostics. Discov Oncol, 2024. 15(1): p. 181. [CrossRef]

- Verweij, F.J., et al., ER membrane contact sites support endosomal small GTPase conversion for exosome secretion. J Cell Biol, 2022. 221(12). [CrossRef]

- He, C., et al., Exosomes derived from endoplasmic reticulum-stressed liver cancer cells enhance the expression of cytokines in macrophages via the STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett, 2020. 20(1): p. 589-600. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M., et al., Identification and functional characterization of multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase1 (Minpp1) isoform-2 in exosomes with potential to modulate tumor microenvironment. PLoS One, 2022. 17(3): p. e0264451. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., S. Hassen, and N. Ali, Changes in cellular levels of inositol polyphosphates during apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem, 2010. 345(1-2): p. 61-8. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., H. Mumtaz, and N. Ali, Role of inositol polyphosphates in programmed cell death. Mol Cell Biochem, 2009. 328(1-2): p. 155-65. [CrossRef]

- Vucenik, I., A. Druzijanic, and N. Druzijanic, Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) and Colon Cancer: From Concepts and First Experiments to Clinical Application. Molecules, 2020. 25(24). [CrossRef]

- Kilaparty, S.P., et al., Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis accompanies enhanced expression of multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase 1 (Minpp1): a possible role for Minpp1 in cellular stress response. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2016. 21(4): p. 593-608. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, A.N., et al., Nanoparticles in cancer theragnostic and drug delivery: A comprehensive review. Life Sci, 2024. 352: p. 122899. [CrossRef]

- Puttasiddaiah, R., et al., Emerging Nanoparticle-Based Diagnostics and Therapeutics for Cancer: Innovations and Challenges. Pharmaceutics, 2025. 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., et al., Rethinking cancer nanotheranostics. Nat Rev Mater, 2017. 2. [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, K., Srinivasan, S., Shanmugam S,, Review of the efficacy of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for cancer treatment,. Biomedical Technology, 2023. 5: p. 109-122. [CrossRef]

- Reda, A., S. Hosseiny, and I.M. El-Sherbiny, Next-generation nanotheranostics targeting cancer stem cells. Nanomedicine (Lond), 2019. 14(18): p. 2487-2514. [CrossRef]

- Fan, D., et al., Nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023. 8(1): p. 293.

- Singh, S.K., et al., Drug delivery approaches for breast cancer. Int J Nanomedicine, 2017. 12: p. 6205-6218.

- Aldhubiab, B., R.M. Almuqbil, and A.B. Nair, Harnessing the Power of Nanocarriers to Exploit the Tumor Microenvironment for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2025. 18(5). [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.E., et al., Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol, 2004. 15(3): p. 440-9.

- Sharifi-Rad, J., et al., Paclitaxel: Application in Modern Oncology and Nanomedicine-Based Cancer Therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021. 2021: p. 3687700. [CrossRef]

- Montero, A.J., et al., Nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol, 2011. 4(3): p. 329-34. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., et al., Therapeutic siRNA for drug-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(12): p. 14727-41. [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A., et al., Recent Advancements in Stimuli Responsive Drug Delivery Platforms for Active and Passive Cancer Targeting. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J., et al., Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2021. 20(2): p. 101-124. [CrossRef]

- Noury, H., et al., AI-driven innovations in smart multifunctional nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery: A mini-review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2025. 210: p. 104701. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.A., et al., "Combo" nanomedicine: Co-delivery of multi-modal therapeutics for efficient, targeted, and safe cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2016. 98: p. 3-18.

- Shen, J., et al., Crosstalk of methylation and tamoxifen in breast cancer (Review). Mol Med Rep, 2024. 30(4). [CrossRef]

- Gan, L., et al., Epigenetic regulation of cancer progression by EZH2: from biological insights to therapeutic potential. Biomark Res, 2018. 6: p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q., et al., An epigenomic approach to therapy for tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Cell Res, 2014. 24(7): p. 809-19. [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.K., P. O’Connell, and Y.A. Aldhamen, Fundamentals to therapeutics: Epigenetic modulation of CD8(+) T Cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 1082195. [CrossRef]

- Achinger-Kawecka, J., et al., The potential of epigenetic therapy to target the 3D epigenome in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2024. 31(3): p. 498-512. [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N., et al., Novel prodrugs of decitabine with greater metabolic stability and less toxicity. Clin Epigenetics, 2019. 11(1): p. 111. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W., et al., Epigenetics-targeted drugs: current paradigms and future challenges. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2024. 9(1): p. 332. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y., et al., Combination therapy with epigenetic-targeted and chemotherapeutic drugs delivered by nanoparticles to enhance the chemotherapy response and overcome resistance by breast cancer stem cells. J Control Release, 2015. 205: p. 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Ranganna, K., et al., Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Multitarget-Directed Epi-Drugs in Blocking PI3K Oncogenic Signaling: A Polypharmacology Approach. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(21). [CrossRef]

- Guefack, M.F. and S. Bhatnagar, Advances in Epigenetic Therapeutics for Breast Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2024. 1465: p. 89-97.

- Chen, J.S., et al., A novel STAT3/ NFkappaB p50 axis regulates stromal-KDM2A to promote M2 macrophage-mediated chemoresistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int, 2023. 23(1): p. 237.

- Soliman, A., Z. Li, and A.V. Parwani, Artificial intelligence’s impact on breast cancer pathology: a literature review. Diagn Pathol, 2024. 19(1): p. 38. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y., Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, Deep learning. Nature, 2015. 521(7553): p. 436-44.

- Madani, M., M.M. Behzadi, and S. Nabavi, The Role of Deep Learning in Advancing Breast Cancer Detection Using Different Imaging Modalities: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 14(21). [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E., et al., A Deep-Learning Solution Identifies HER2 Negative Cases and Provides ER and PR Results From H&E-Stained Breast Cancer Specimens: A Blind Validation Study. Clin Breast Cancer, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A., et al., Deep learning-enabled medical computer vision. NPJ Digit Med, 2021. 4(1): p. 5. [CrossRef]

- Nicolis, O., D. De Los Angeles, and C. Taramasco, A contemporary review of breast cancer risk factors and the role of artificial intelligence. Front Oncol, 2024. 14: p. 1356014. [CrossRef]

- Yala, A., et al., A Deep Learning Mammography-based Model for Improved Breast Cancer Risk Prediction. Radiology, 2019. 292(1): p. 60-66. [CrossRef]

- Ling, J., et al., Artificial intelligence-driven discovery of YH395A: A novel TGFbetaR1 inhibitor with potent anti-tumor activity against triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Commun Signal, 2025. 23(1): p. 326. [CrossRef]

- Bendani, H., et al., Revolutionizing breast cancer immunotherapy by integrating AI and nanotechnology approaches: review of current applications and future directions. Bioelectron Med, 2025. 11(1): p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S., et al., A carrier-free ultrasound-responsive polyphenol nanonetworks with enhanced sonodynamic-immunotherapy for synergistic therapy of breast cancer. Biomaterials, 2025. 317: p. 123109. [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M., U. Habiba, and A. Maryam, Next-generation cancer therapeutics: unveiling the potential of liposome-based nanoparticles through bioinformatics. Mikrochim Acta, 2025. 192(7): p. 428. [CrossRef]

- Ghandikota, S.K. and A.G. Jegga, Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in drug repurposing. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 2024. 205: p. 171-211.

- Witten, I., et al., Future views on neuroscience and AI. Cell, 2024. 187(21): p. 5809-5813. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., et al., HER2-Targeted Nanoliposome Therapy Activates Immune Response by Converting Cold to Hot Breast Tumors. Technol Cancer Res Treat, 2025. 24: p. 15330338251356387. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J., High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med, 2019. 25(1): p. 44-56. [CrossRef]

- Guan, H., et al., Federated learning for medical image analysis: A survey. Pattern Recognit, 2024. 151.

- Arravalli, T., et al., Detection of breast cancer using machine learning and explainable artificial intelligence. Sci Rep, 2025. 15(1): p. 26931. [CrossRef]

- Shen, S., et al., From virtual to reality: innovative practices of digital twins in tumor therapy. J Transl Med, 2025. 23(1): p. 348. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K., G. Gouda, and R. Vadde, Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Mediating Resistance to Anti-HER2 Antibodies. Crit Rev Oncog, 2024. 29(4): p. 43-54. [CrossRef]

| Gene Penetrance | Genes Involved |

|---|---|

| High Penetrance Genes | BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN, CDH1, STK11, TP53 |

| Moderate Penetrance Genes | CHEK2, BRIP1, ATM, PALB2 |

| Low Penetrance Genes | FGFR2, LSP1, MAP3K1, TGF-β1, TOX3, RECQL, MUTYH, MSH6, NF1, NBN |

| Risk Factor(s) | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Increased incidence with age likely due to cumulative DNA damage and reduced cellular repair mechanisms. | [4,31] |

| Family History | Inherited germline mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 predispose individuals to hereditary C. | [32] |

| Personal History | A prior diagnosis of BC in one breast significantly increases the risk of developing cancer in the contralateral breast. | [37] |

| Early Menarche/Late Menopause | Prolonged lifetime exposure to endogenous estrogen and progesterone, increasing the number of menstrual cycles (Menarche <12 years or menopause >55 years). | [35] |

| Reproductive History | Nulliparity (never having given birth) or first childbirth after age 30 are associated with increased risk, possibly due to altered hormonal profiles and breast tissue development. | [38] |

| Dense Breast Tissue | Higher mammographic density indicates a greater proportion of glandular and fibrous tissue compared to fatty tissue, which is associated with an increased risk and can complicate early detection by mammography. | [39] |

| Lifestyle Factors | Alcohol consumption, obesity (particularly postmenopausal), and smoking are established modifiable risk factors. Alcohol can increase estrogen levels; obesity is linked to chronic inflammation and altered hormone metabolism; smoking introduces carcinogens. | [34,40] |

| Hormonal Factors | Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), particularly combined estrogen and progestin formulations, can increase BC risk by increasing circulating hormone levels. | [41] |

| Radiation Exposure | Exposure to ionizing radiation, especially during youth (e.g., treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma), can damage breast tissue DNA and increase the long-term risk. | [42] |

| Diethylstilbestrol (DES) | In utero exposure to DES (prescribed between 1940–1971 in the U.S. to prevent miscarriage) is a known risk factor for BC in both the exposed women and their daughters. | [43] |

| Model | Key contributions | Pros | Cons | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Cell Lines | Mechanistic discoveries in ER, HER2, and efflux resistance | Cheap, reproducible, high-throughput | Poor physiological relevance | [68,69,70] |

| 3D Spheroids/ Organoids | Hypoxia, CSC-driven resistance, TME influence | Mimics architecture, patient-derived | Complex culture, batch variability | [68,69,73,76], |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Resistance in heterogeneous tumors, therapy validation | High translational relevance | Expensive, lacks human immunity | [69,76,77], |

| Genetically Engineered Mice (GEMMs) | DNA repair defects, immune-competent resistance models | Immune-competent, spontaneous tumors | Genetically rigid, costly | [69,77], |

| CTC Models | Insights into metastasis, mesenchymal resistance | Real-time, metastatic focus | Difficult to culture and expand | [77,78] |

| In Silico Models (AI-based) | Predictive modeling of resistance, target discovery | Fast, scalable, cost-effective | Needs biological validation | [69] |

| Feature | Ibex Prostate Pathology | OnQ™ Prostate Imaging | AI in Breast Cancer (ProFound 4.0) | AI in Breast Cancer (Clairity Breast) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Status | 510(k) cleared (May 2024) | 510(k) cleared (Feb 2025) | 510(k) cleared (Nov 2024) | De Novo clearance (June 2025) |

| Modality | AI-based analysis of H&E-stained biopsy slides | RSI-enhanced diffusion-weighted MRI | Mammography (with or without prior imaging) | AI-based analysis of screening mammograms |

| Purpose | Digital pathology interpretation, cancer detection | Improved lesion characterization, biopsy targeting | Enhanced sensitivity and risk prediction | Detection of subtle imaging features predictive of future cancer |

| Clinical Utility | Gleason scoring, decision support for pathologists | Improves PI-RADS accuracy, reduces inter-reader variability | Improves detection in dense breasts, risk stratification | Predicts 5-year BC risk from routine mammography |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).