Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

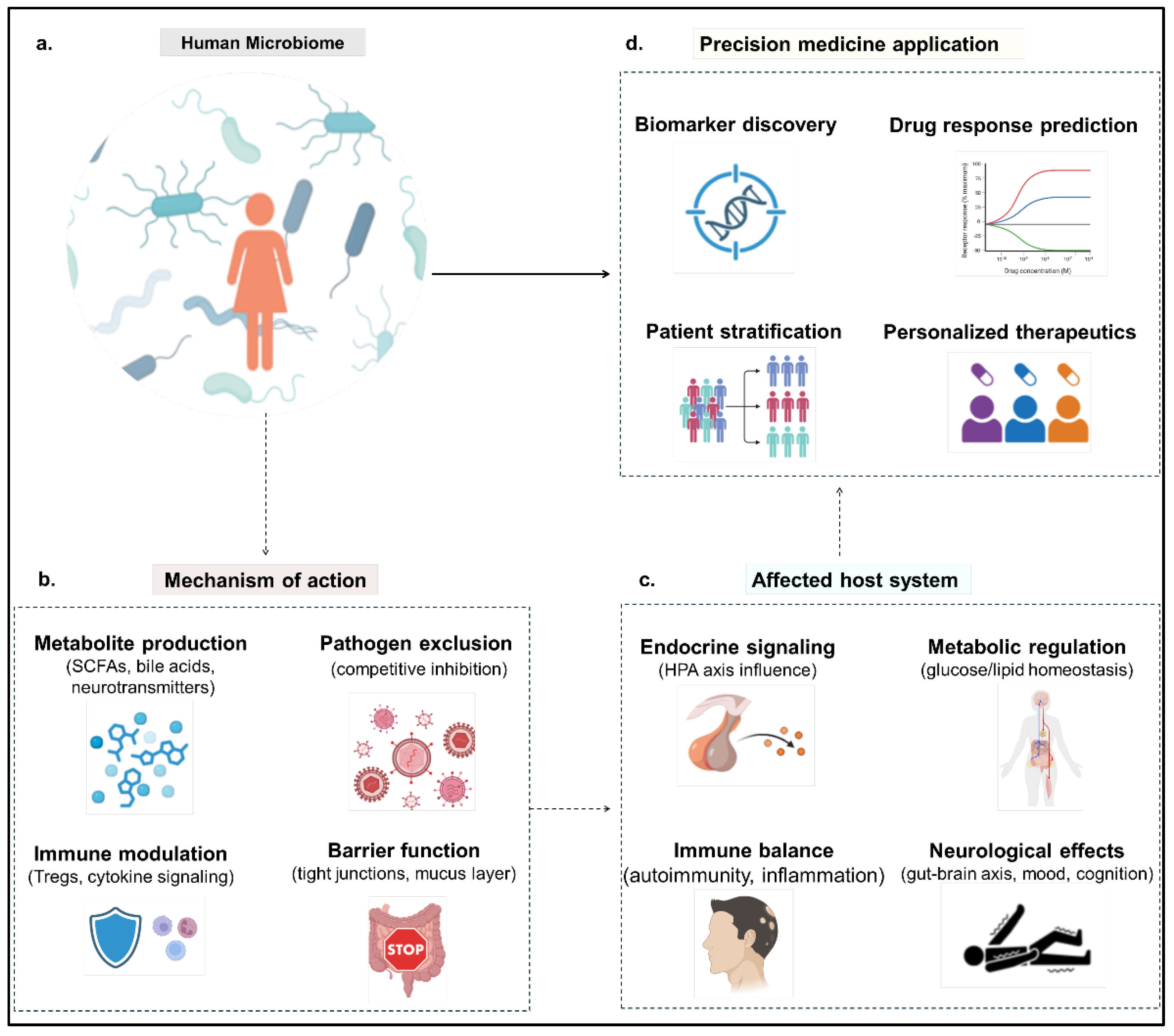

Mechanistic Foundations of Microbiome-Driven Precision Medicine

Multi-Omics Approaches to Microbiome Profiling

Metagenomics and Beyond

Integration Strategies: Temporal and Spatial Resolution

Computational Frameworks and Machine Learning

Case Studies and Translational Examples

Clinical Applications and Current Landscape

Microbiome-Based Diagnostics and Prognostics

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) and Engineered Probiotics

Role in Immunotherapy Response

Stratification of Patients Using Microbial Biomarkers

Challenges and Limitations

Future Directions and Research Gaps

Personalized Pre/Probiotics and Diet–Microbiome Interfaces

Synthetic Biology Tools for Precision Microbiome Editing

Integrating Microbiome Data into EHRS and Clinical Decision Support

Regulatory Frameworks and Commercialization Prospects

Conclusions

Author Declarations

References

- C. Jf et al., “The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis,” Physiological reviews, vol. 99, no. 4, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Lloyd-Price et al., “Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases,” Nature, vol. 569, no. 7758, pp. 655–662. May 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Franzosa et al., “Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease,” Nat Microbiol, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 293–305, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. J et al., “A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes,” Nature, vol. 490, no. 7418, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Ws, “Cancer and the microbiota,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 348, no. 6230, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Hj et al., “Therapeutic Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Functional Bowel Disorders,” Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. B. Mutalub et al., “Gut Microbiota Modulation as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy in Cardiometabolic Diseases,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 17, Art. no. 17, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. M et al., “Multiomics approach reveals the comprehensive interactions between nutrition and children’s gut microbiota, and microbial and host metabolomes,” Nutrition journal, vol. 24, no. 1, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Y and H. Oj, “Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota,” Immunity, vol. 46, no. 4, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Jl and M. Sk, “Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 107, no. 27, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Koh, F. De Vadder, P. Kovatcheva-Datchary, and F. Bäckhed, “From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites,” Cell, vol. 165, no. 6, pp. 1332–1345, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Bd et al., “Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 330, no. 6005, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- V. Gopalakrishnan et al., “Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6371, pp. 97–103, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Ad et al., “Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment,” Cell host & microbe, vol. 14, no. 2, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Tr et al., “Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease,” Cell, vol. 167, no. 6, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Jk et al., “Human genetics shape the gut microbiome,” Cell, vol. 159, no. 4, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Ka, F. K. Ka, F. J, and B. F, “Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates,” Nature reviews. Microbiology, vol. 19, no. 2, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. M et al., “Dynamics of metatranscription in the inflammatory bowel disease gut microbiome,” Nature microbiology, vol. 3, no. 3, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. X et al., “The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment,” Nature medicine, vol. 21, no. 8, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A, P. J, and S. H, “Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease,” Cell host & microbe, vol. 23, no. 6, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Valles-Colomer et al., “The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression,” Nat Microbiol, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 623–632, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Aj et al., “Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans,” Cell host & microbe, vol. 25, no. 6, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. D et al., “Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses,” Cell, vol. 163, no. 5, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu et al., “Single-cell sequencing to multi-omics: technologies and applications,” Biomarker Research, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 110, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., “Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale,” Nat Methods, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 333–337, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. R et al., “MOFA+: a statistical framework for comprehensive integration of multi-modal single-cell data,” Genome biology, vol. 21, no. 1. May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Bd, L. Na, R. Mt, W. J, and S. Pd, “A Framework for Effective Application of Machine Learning to Microbiome-Based Classification Problems,” mBio, vol. 11, no. 3, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Lf et al., “Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 369, no. 6510, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.-S. H et al., “Model of personalized postprandial glycemic response to food developed for an Israeli cohort predicts responses in Midwestern American individuals,” The American journal of clinical nutrition, vol. 110, no. 1, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Am et al., “Metagenomic analysis of colorectal cancer datasets identifies cross-cohort microbial diagnostic signatures and a link with choline degradation,” Nature medicine, vol. 25, no. 4, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- van, N. E et al., “Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile,” The New England journal of medicine, vol. 368, no. 5, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Dw et al., “Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study,” Microbiome, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Charbonneau, V. M. Isabella, N. Li, and C. B. Kurtz, “Developing a new class of engineered live bacterial therapeutics to treat human diseases,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 1738, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Iy et al., “Engineered probiotic Escherichia coli can eliminate and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa gut infection in animal models,” Nature communications, vol. 8, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Reddi et al., “Fecal microbiota transplantation to prevent acute graft-versus-host disease: pre-planned interim analysis of donor effect,” Nat Commun, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 1034, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Khanna et al., “SER-109: An Oral Investigational Microbiome Therapeutic for Patients with Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection (rCDI),” Antibiotics, vol. 11, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Dimopoulou et al., “Potential of using an engineered indole lactic acid producing Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in a murine model of colitis,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 17542, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Mok et al., “Synbiotic-driven modulation of the gut microbiota and metabolic functions related to obesity: insights from a human gastrointestinal model,” BMC Microbiology, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 250, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Dedrick et al., “Phage Therapy of Mycobacterium Infections: Compassionate Use of Phages in 20 Patients With Drug-Resistant Mycobacterial Disease,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 103–112, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. B et al., “Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 359, no. 6371, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. En et al., “Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 371, no. 6529, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Y et al., “Gut Microbiota Offers Universal Biomarkers across Ethnicity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosis and Infliximab Response Prediction,” mSystems, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. B et al., “The oral microbiota in colorectal cancer is distinctive and predictive,” Gut, vol. 67, no. 8, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Le Chatelier et al., “Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers,” Nature, vol. 500, no. 7464, pp. 541–546, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Falony et al., “Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation,” Science, vol. 352, no. 6285, pp. 560–564, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Vk et al., “A predictive index for health status using species-level gut microbiome profiling,” Nature communications, vol. 11, no. 1, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Lloyd-Price et al., “Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project,” Nature, vol. 550, no. 7674, pp. 61–66, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. N, Z. D, K. T, S. E, and E. E, “Taking it Personally: Personalized Utilization of the Human Microbiome in Health and Disease,” Cell host & microbe, vol. 19, no. 1, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. R, A. Cc, W. O, K. R, and H. C, “The microbiome quality control project: baseline study design and future directions,” Genome biology, vol. 16, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Knight et al., “Best practices for analysing microbiomes,” Nature Reviews Microbiology, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 410–422, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Hs, P. M, and L. B, “Ethical challenges in conducting and the clinical application of human microbiome research,” Journal of medical ethics and history of medicine, vol. 16, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, J. L. A. Fiala, and D. Lowery, “Modulating the human microbiome with live biotherapeutic products: intellectual property landscape,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 224–225, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. D et al., “Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota,” Nature, vol. 555, no. 7695, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Kp, G. Sw, S. Po, F. Hj, and D. Sh, “The influence of diet on the gut microbiota,” Pharmacological research, vol. 69, no. 1, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. M and van H. V. Je, “Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota,” Trends in microbiology, vol. 23, no. 6, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. N, S. J, and E. E, “You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota,” Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M, C. Rj, and L. Tk, “Microbiome therapeutics - Advances and challenges,” Advanced drug delivery reviews, vol. 105, no. Pt A, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. C, C. Sp, C. V, Y. Sj, and W. Hh, “Metagenomic engineering of the mammalian gut microbiome in situ,” Nature methods, vol. 16, no. 2, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S.-F. R. Sm et al., “A longitudinal big data approach for precision health,” Nature medicine, vol. 25, no. 5. May 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Ej, “A decade of digital medicine innovation,” Science translational medicine, vol. 11, no. 498, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Al, B. Y, and S. Ja, “The human skin microbiome,” Nature reviews. Microbiology, vol. 16, no. 3, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. N. Ga, “Drugs and Devices: Comparison of European and U.S. Approval Processes,” JACC. Basic to translational science, vol. 1, no. 5, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Kashyap, N. Chia, H. Nelson, E. Segal, and E. Elinav, “Microbiome at the Frontier of Personalized Medicine,” Mayo Clinic proceedings, vol. 92, no. 12, p. 1855, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E.-J. Song and J.-H. Shin, “Personalized Diets based on the Gut Microbiome as a Target for Health Maintenance: from Current Evidence to Future Possibilities,” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 32, no. 12, p. 1497, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Gilbert, M. J. Blaser, J. G. Caporaso, J. K. Jansson, S. V. Lynch, and R. Knight, “Current understanding of the human microbiome,” Nat Med, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 392–400, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Proctor et al., “The Integrative Human Microbiome Project,” Nature, vol. 569, no. 7758, pp. 641–648. May 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Zy and L. Sk, “The Human Gut Microbiome - A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease,” Frontiers in microbiology, vol. 9, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. D, “Microbiome Research Is Becoming the Key to Better Understanding Health and Nutrition,” Frontiers in genetics, vol. 9, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. A et al., “Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity,” Science (New York, N.Y.), vol. 352, no. 6285, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Levy, A. A. Kolodziejczyk, C. A. Thaiss, and E. Elinav, “Dysbiosis and the immune system,” Nat Rev Immunol, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 219–232, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. N et al., “Personalized Gut Mucosal Colonization Resistance to Empiric Probiotics Is Associated with Unique Host and Microbiome Features,” Cell, vol. 174, no. 6, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Sa, H. F, L. L, S. H, and de V. Wm, “Intestinal microbiome landscaping: insight in community assemblage and implications for microbial modulation strategies,” FEMS microbiology reviews, vol. 41, no. 2, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Md et al., “The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship,” Scientific data, vol. 3, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. van de Guchte, H. M. Blottière, and J. Doré, “Humans as holobionts: implications for prevention and therapy,” Microbiome, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 81. May 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Hou et al., “Microbiota in health and diseases,” Sig Transduct Target Ther, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 135, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Relman, “Thinking about the microbiome as a causal factor in human health and disease: philosophical and experimental considerations,” Curr Opin Microbiol, vol. 54, pp. 119–126, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

| Microbiome Feature | Relevance to Precision Medicine | Omics Approaches Used | Specific Insights Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic composition | Determines disease-linked dysbiosis; informs microbial biomarkers | Metagenomics (16S rRNA, WGS) | Detection of microbial signatures across diseases |

| Functional potential | Reveals biosynthetic capacities, AMR genes, virulence traits | Metagenomics, Metaproteomics | Prediction of functional shifts before phenotypic onset |

| Gene expression activity | Identifies active microbial pathways | Metatranscriptomics | Differentiation between latent and active microbial functions |

| Metabolite production | Directly influences host metabolism and immune signaling | Metabolomics (LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR) | Discovery of disease-linked metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, bile acids) |

| Microbe–host crosstalk | Underpins immunomodulation, gut-brain axis, inflammation | Host transcriptomics + microbial omics integration | Host responses to microbial fluctuations; immune-metabolic links |

| Temporal dynamics | Captures microbiome fluctuations linked to diet, therapy, disease | Longitudinal multi-omics + time-series modeling | Personalized monitoring; real-time tracking of interventions |

| Ecological interactions | Community stability, competition, and resilience | Systems biology, co-occurrence networks, integrated multi-omics | Network-level vulnerabilities and keystone species identification |

| Therapy | Mechanism | Disease Context | Clinical Status | Key Limitations | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT) | Full microbiome ecosystem transfer | rCDI, UC, graft-vs-host |

Approved for rCDI, trials ongoing for others | Donor variability, infection risk | FDA-2022-176 [35] |

| Live biotherapeutic product (SER-109) | Enriched Firmicutes spores | rCDI | Phase III completed (Seres) | Targeted efficacy, not broad spectrum | [36] |

| Engineered E. coli nissle | SCFA biosynthesis, barrier repair | IBD, inflammation | Preclinical | Safety, horizontal gene transfer | [37] |

| Precision synbiotics | Selective prebiotic + probiotic strains | T2D, obesity | Phase I/II | Response variability, diet dependency | [38] |

| Phage therapy | Targeted depletion of pathogenic species | Crohn’s, MDR infections |

Experimental use | Resistance evolution, narrow targeting | [39] |

| Category | Current State | Ideal Future State | Actions Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data standardization | Non-uniform metadata, poor reproducibility | Harmonized pipelines, shared ontologies | Adoption of MIxS, MBQC; global repositories |

| Clinical integration | Minimal use in EHRs or decision support | Embedded microbiome metrics in diagnostics | Interoperable data standards, pilot deployments |

| Personalization of therapies | Broad-spectrum approaches | Microbiome-informed individualized treatment | Multi-omics modeling, n=1 trial design |

| Regulatory guidance | Patchy, product-specific approvals | Clear frameworks for diagnostics, probiotics, live biotherapeutics | International regulatory harmonization |

| Ethical & legal oversight | Limited, fragmented by jurisdiction | Global ELSI framework respecting identifiability & consent | Policy dialogue, equitable benefit-sharing models |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).