1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by progressive cognitive decline and memory impairment (Zhong et al., 2024). The intricate relationship between the gut microbiome and the brain, often referred to as the microbiota-gut-brain axis, is increasingly recognized as a critical factor influencing neurological health and disease (Zheng et al., 2016). The central nervous system (CNS) and the gastrointestinal tract are interconnected, with the CNS playing a pivotal role in regulating gut function and homeostasis (Zhu et al., 2017). Mounting evidence suggests that the gut microbiota, along with its metabolic products, interacts with the enteric nervous system, the autonomic nervous system, the neural-immune system, the neuroendocrine system, and the central nervous system, establishing a complex communication network (Martin et al., 2018) (Wang & Wang, 2016) (Ding et al., 2020).

Disruptions in the gut microbial composition, termed dysbiosis, are implicated in the development and progression of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (Kandpal et al., 2022). Furthermore, the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases is escalating, posing substantial socioeconomic challenges to healthcare systems globally (Zacharias et al., 2022). Sex differences in the gut microbiome may contribute to disparities observed in Alzheimer’s disease risk and pathology (Forbes et al., 2019) (Han et al., 2023). Specifically, irritable bowel syndrome can be considered an example of the disruption of these complex relationships, and a better understanding of these alterations might provide new targeted therapies (Carabotti et al., 2015).

The AD-BXD mouse model (Neuner et al., 2018), integrating the 5xFAD transgene with genetically diverse BXD strains, offers a powerful platform to dissect interactions between host genetics, sex, and the microbiome (Chakrabarti et al., 2022). Recent research has suggested that sex-specific differences in the gut microbiome may contribute to disparities observed in Alzheimer’s disease risk and pathology, with a study by Dennison et al. (2021) reporting that female AD patients experience more rapid cognitive decline compared to males.

Understanding the functional aspects of the gut microbiome in AD-BXD mice could provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of this complex disease. By identifying sex-specific metabolic modules and their potential links to neurodegeneration, this research aims to advance our knowledge of the gut-brain axis in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Functional metagenomics, which examines the genetic material from microbial communities in environmental samples, has not been explored in AD-BXD mice.

This study employed the iMGMC pipeline (Lesker et al., 2020), an integrated Mouse Gut Metagenome Catalog, to compare male and female gut microbial functions at the KO and pathway levels, aiming to uncover sex-specific metabolic modules and their potential connections to neurodegeneration.

2. Methods and Materials

To address whether gut microbial functions differ between male and female Alzheimer’s disease BXD mice, the study leveraged shotgun metagenomic data from ten 6-month-old 5×FAD BXD mice (Neuner et al., 2018). Ten randomly selected fecal metagenomes from 5×FAD BXD mice (five male, five female) were processed in this study.

Table 1 lists the original FASTQ file prefixes, the animal sex, and the abbreviated short label used throughout the manuscript. All raw sequence reads (FASTQ files) have been deposited in the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (Synapse ID syn17016211;

https://doi.org/10.7303/syn17016211).

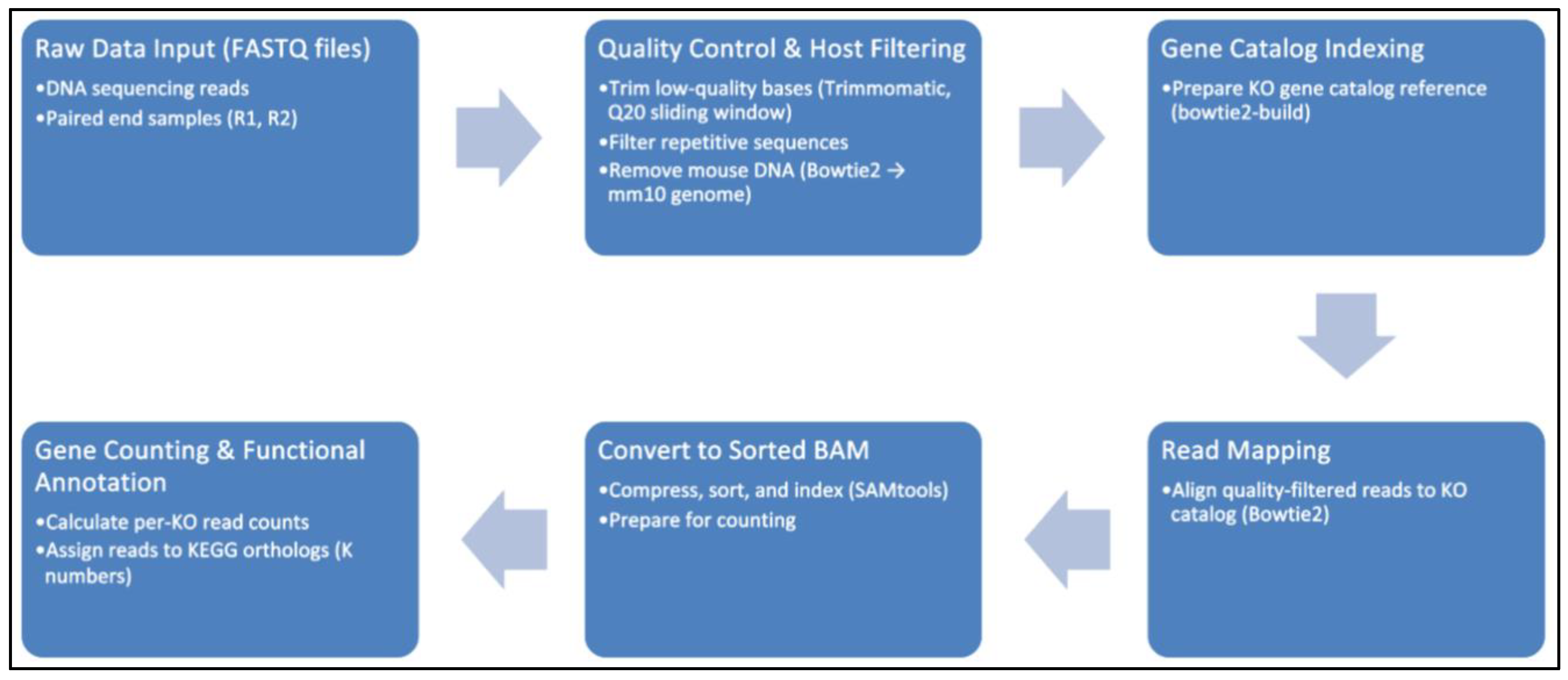

2.1. Data Processing and Functional Profiling (Computational Pipeline)

The raw sequencing reads were preprocessed by trimming adapters, filtering for quality, and removing host (mouse) sequences. The resulting microbial reads were aligned to a comprehensive catalog of KEGG Orthologs (KOs) from the integrated Mouse Gut Metagenome Catalog (iMGMC). KO counts were computed for each sample, normalized to counts-per-million, and log₂-transformed to stabilize the variance.

Figure 1.

Metagenomic Functional Profiling Pipeline.

Figure 1.

Metagenomic Functional Profiling Pipeline.

2.2. Diversity and Abundance Analyses

The Shannon diversity index was calculated on the KO profiles to assess α-diversity, and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was used to perform principal coordinate analysis for evaluating β-diversity. The top 20 most abundant KOs across all samples were visualized in a heatmap.

2.3. Differential KO Abundance

Welch’s two-sample t-test was employed to compare the log₂-transformed counts-per-million (log₂CPM) of each KO between the male and female groups. Nominal p-values were plotted against log₂ fold-change in a volcano plot, and sex-biased KOs were identified. Although no KOs survived false discovery rate correction at the 0.05 significance level, the results based on nominal p-values were retained.

2.4. Sex-Split KEGG Pathway Reconstruction

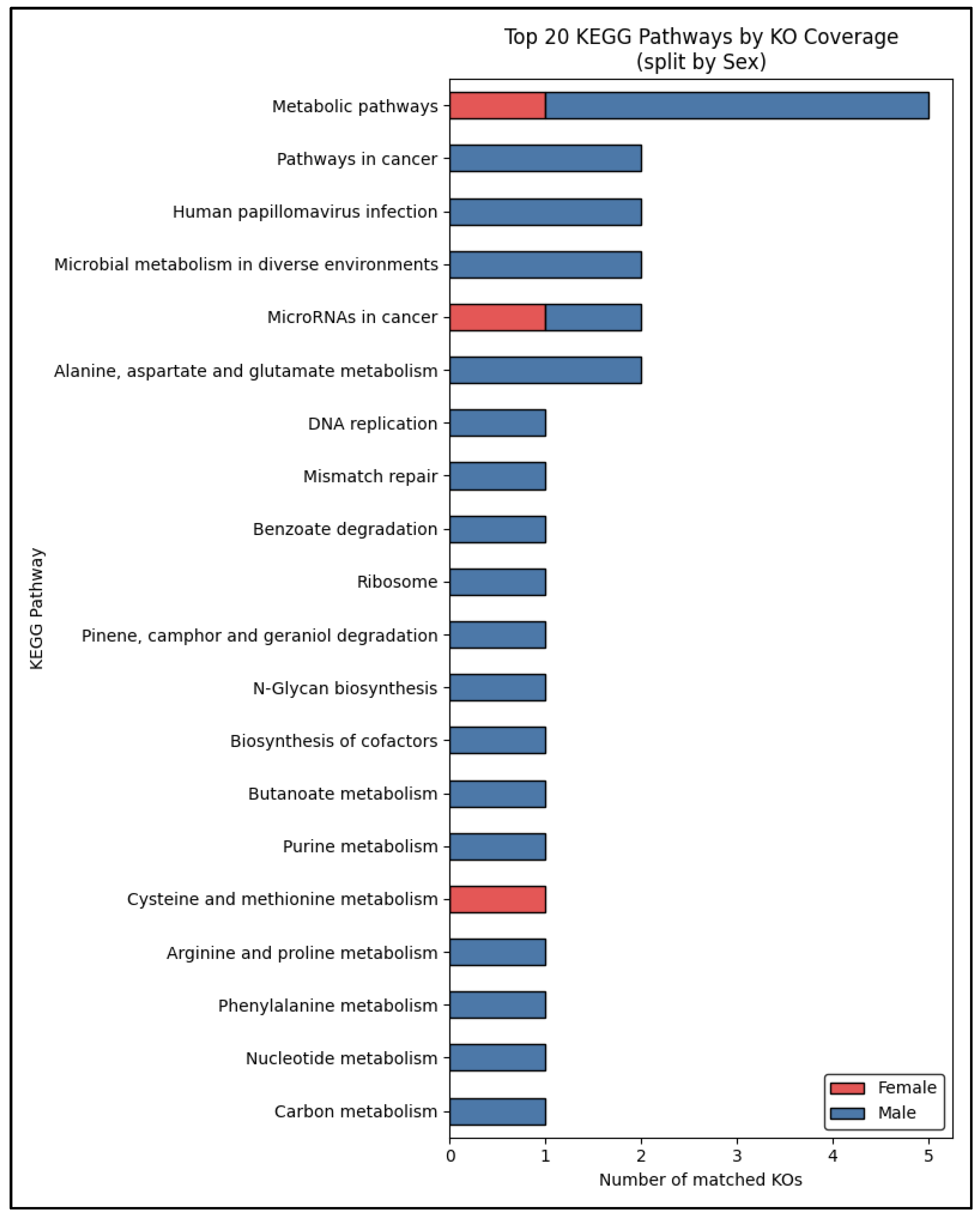

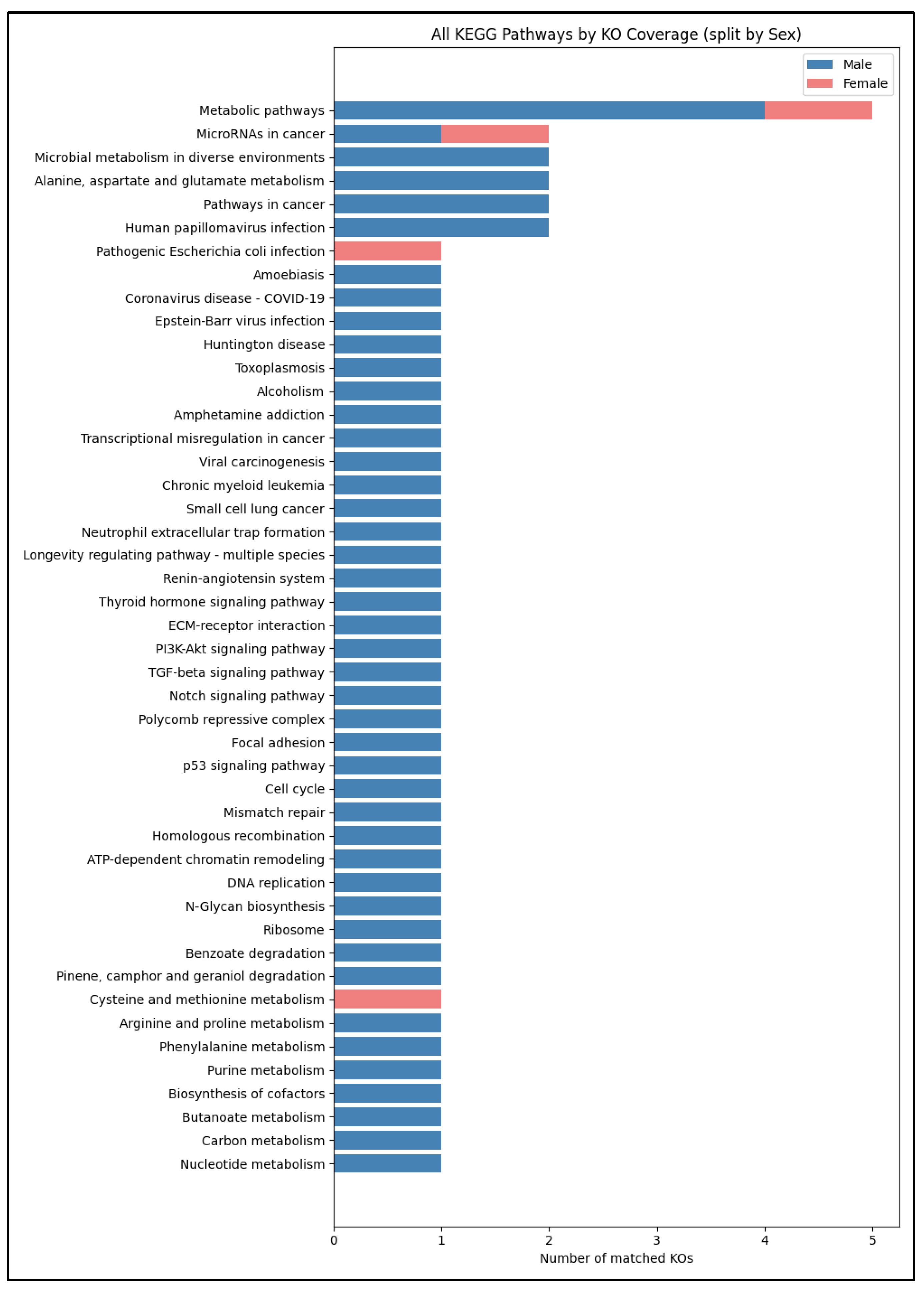

The male- and female-biased KOs were formatted and uploaded to the KEGG Reconstruct tool (Kanehisa et al., 2021; Kanehisa & Sato, 2019) to map them onto KEGG pathway maps. The pathway maps with matching KOs were extracted, and the KO counts per pathway were tallied separately for male and female samples. A stacked bar plot was generated to visualize the male versus female coverage across all 46 pathways.

3. Results

The functional mapping summary (

Table 2) demonstrates consistent sequencing depth (6.4–9.3 M paired reads) and mapping efficiency across all ten AD-BXD samples, with 3.2–7.9% of reads assigned to known KOs. Female samples exhibited slightly higher maximum gene-mapping rates (up to 7.9%) than male samples, though overall rates were comparable between sexes.

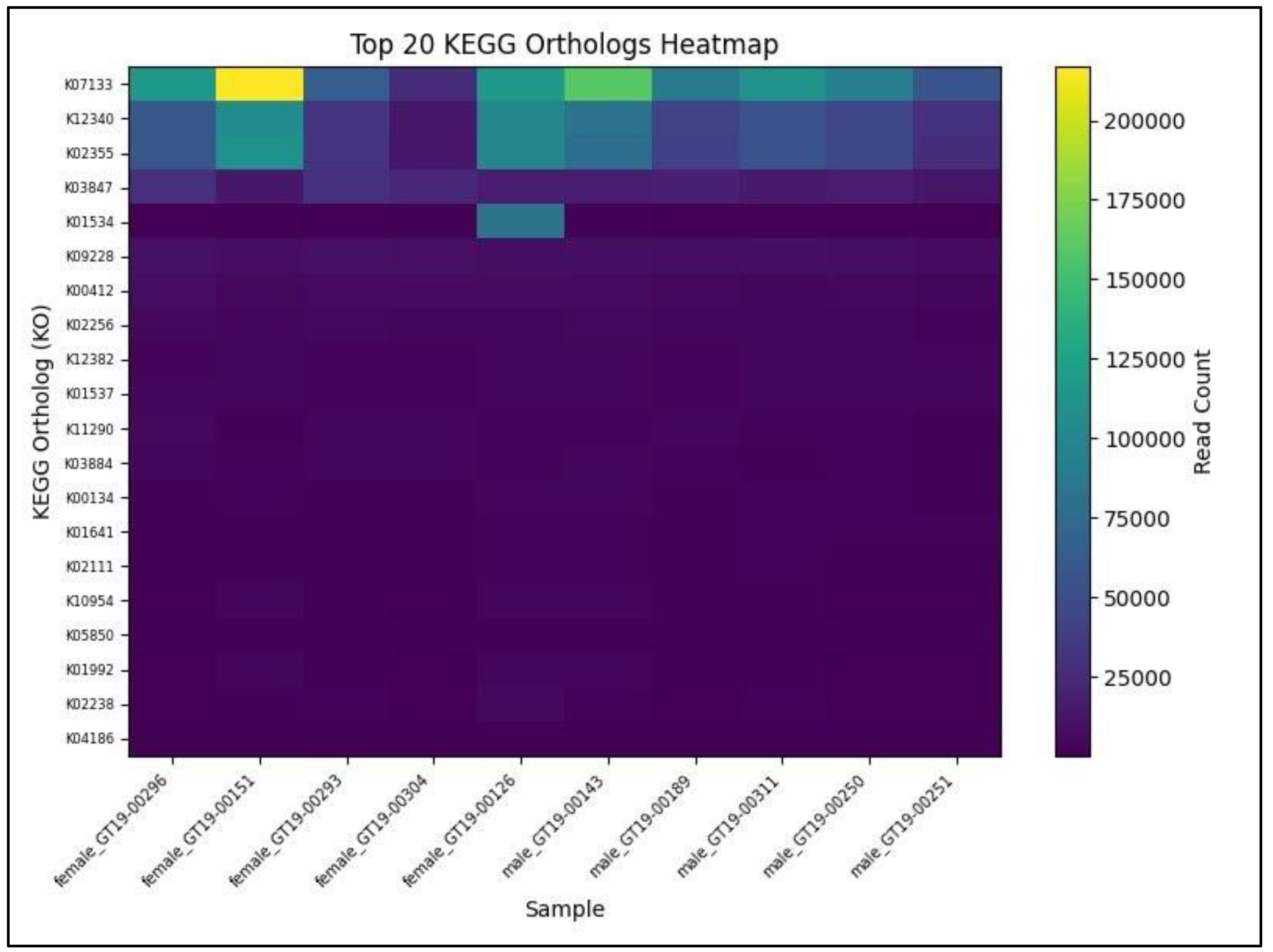

Figure 2 presents a heatmap of the top 20 most abundant KOs detected across ten AD-BXD gut microbiome samples, with female profiles arrayed on the left and male profiles on the right. The transporter substrate-binding protein K07133 emerges as the single highest-count KO, reaching its peak in sample female_GT19-00151, followed by glycerol kinase K12340, which likewise concentrates in that same female sample.

Several core metabolic KOs, including K02355, K02256, and K01534, exhibit consistently high counts in all samples, indicating a shared baseline of nutrient uptake and primary metabolic functions. In contrast, lower-abundance KOs such as K04186, K05850, and K01992 are detected at modest levels across nearly every sample, reflecting more specialized or conditionally expressed functions. Sex-specific patterns become apparent in the relative prominence of these features: female samples display sharp peaks for K07133 and K12340, suggesting enrichment of high-capacity transport and glycerol phosphorylation pathways, whereas male samples distribute read counts more evenly across a broader set of KOs, indicative of greater functional diversity.

3.1. Alpha Diversity of KO Profiles

Shannon diversity was calculated for each sample using normalized KO abundances as an α-diversity metric, capturing both the richness (number of distinct KOs) and evenness (distribution of counts across KOs) of the gut functional profiles (

Table 3). Female samples displayed a wider range of diversity values (2.79–4.17) in contrast to male samples (3.25–3.53), with the peak Shannon index recorded in sample female_GT19-00304 (4.17) and the lowest found in female_GT19-00151 (2.79). Male profiles clustered more tightly between 3.25 and 3.53, indicating a comparatively uniform functional complexity. Overall, mean Shannon diversity did not differ dramatically by sex, suggesting that although specific KOs vary between male and female microbiomes, the total functional richness and evenness remain broadly similar across the ten AD-BXD samples.

3.2. Multidimensional Scaling of Functional Profiles

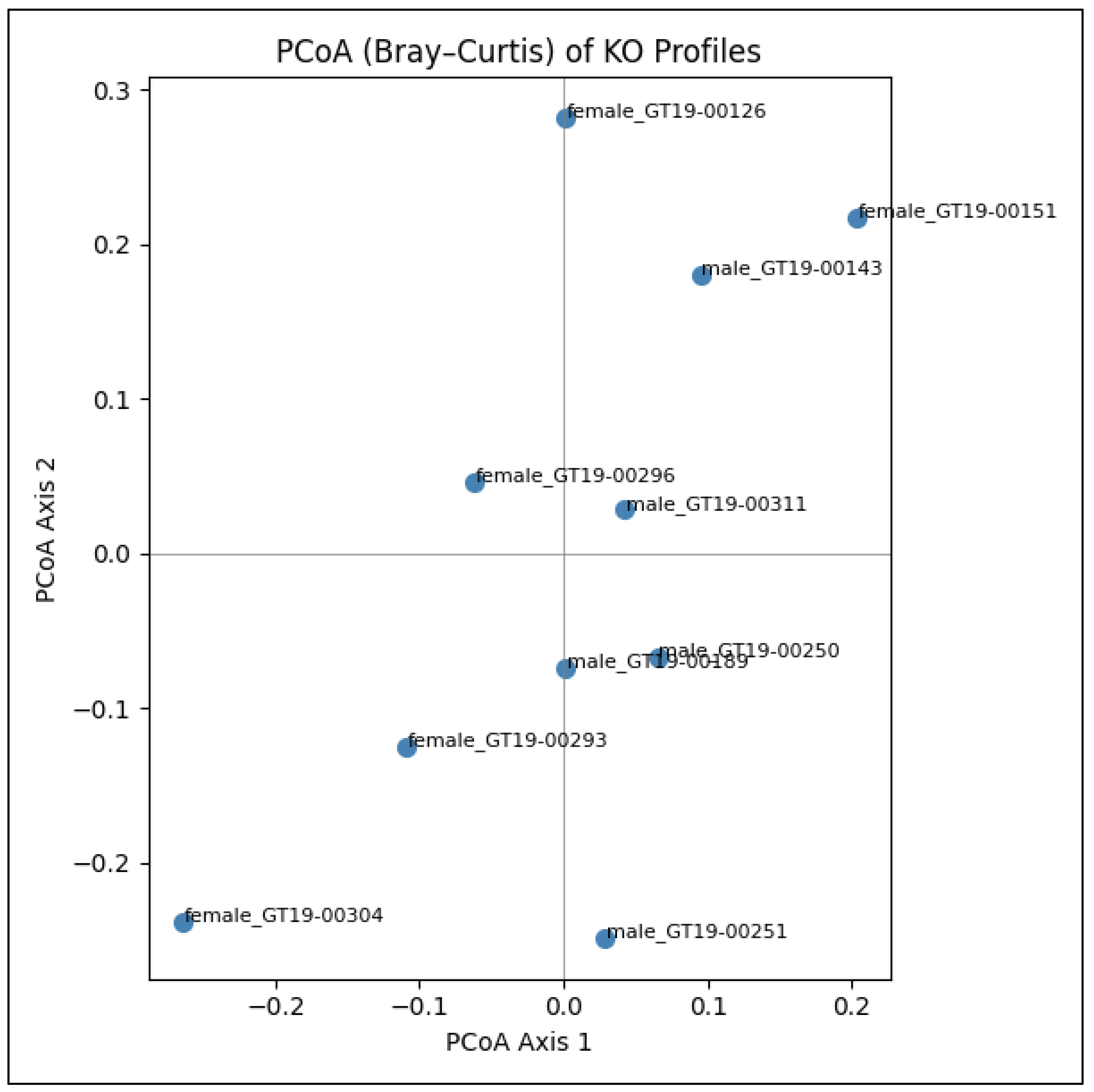

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was performed on the Bray–Curtis distance matrix calculated from the KO abundance profiles to visualize the β-diversity of gut microbial functions across the ten AD-BXD samples (

Figure 3). Bray–Curtis was chosen because it emphasizes differences in shared abundances while down-weighting joint absences, making it well suited for compositional count data. PCoA then projects these pairwise distances into a two-dimensional space that best preserves the original dissimilarities.

The resulting plot shows that male and female samples do not form completely distinct clusters; instead, they are largely intermingled. A central “cloud” of six samples (mix of sexes) spans approximately –0.1 to +0.1 on both axes, indicating broadly similar functional repertoires for most mice. Within this core group, female_GT19-00296 and male_GT19-00311 virtually overlap, reflecting nearly identical KO profiles. A mini-cluster comprising female_GT19-00126, female_GT19-00151, and male_GT19-00143 occupies the top-right quadrant (higher Axis 2), suggesting a shared enrichment of certain functions in these three samples.

Two samples appear as outliers: female_GT19-00304 sits in the bottom-left quadrant (Axis 1 ≈ –0.23, Axis 2 ≈ –0.23), marking it as the most functionally divergent; male_GT19-00251 also lies apart, slightly below the horizontal axis but near the center line, indicating moderate divergence on Axis 2. Overall, the PCoA demonstrates substantial inter-mouse variation in KO composition but shows that sex alone is not the primary driver of global functional differences in this cohort.

3.3. Differential KO Abundance (Male vs. Female)

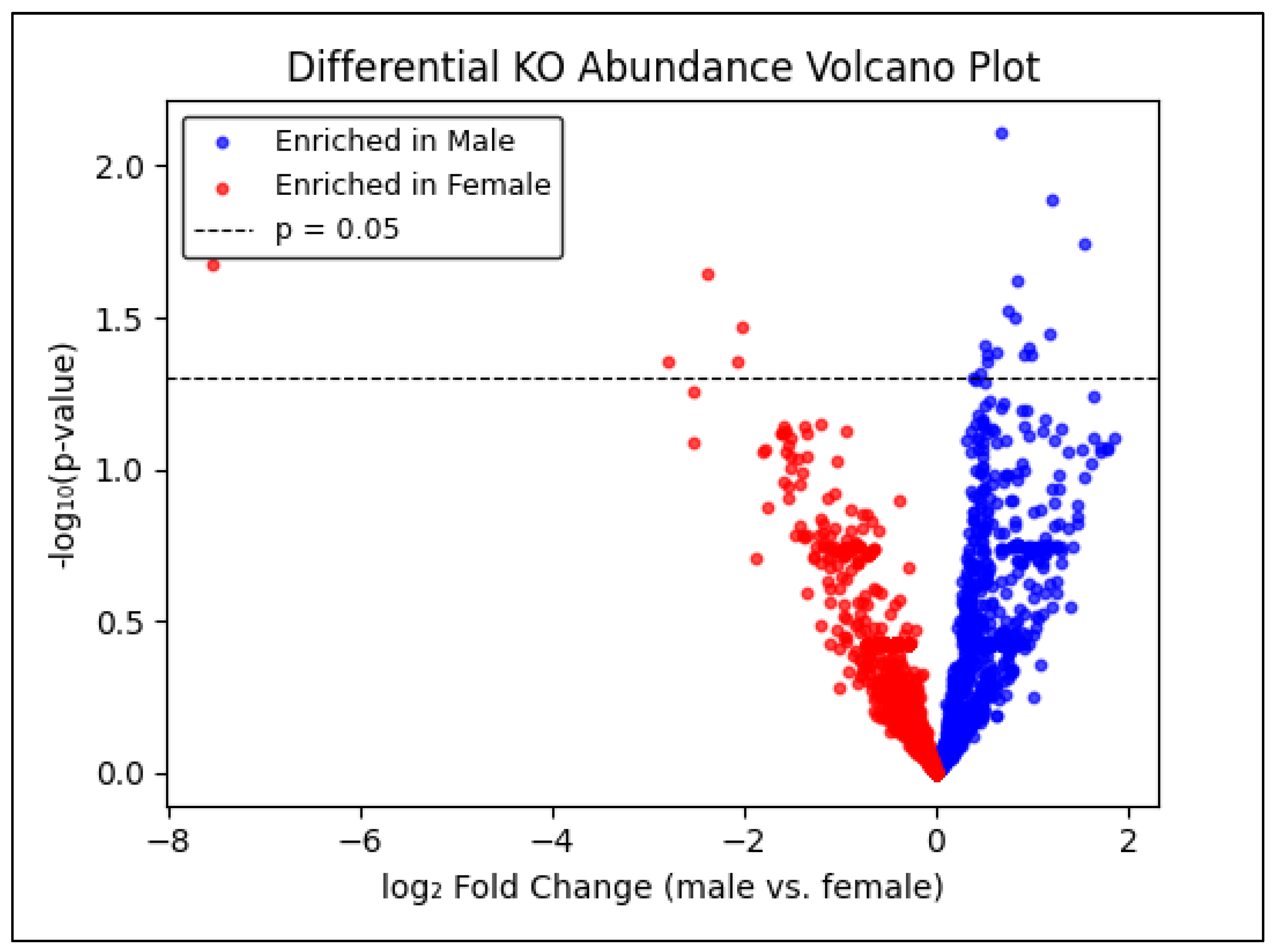

To pinpoint specific microbial functions that differ by sex, raw KO counts were normalized to counts-per-million (CPM) and log₂(CPM + 1)–transformed. Welch’s two-sample t-tests compared male versus female log₂CPM values for each KO, yielding raw p-values. Although false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment (Benjamini–Hochberg) eliminated all hits at padj < 0.05, a nominal threshold of p < 0.05 identified 21 KOs with sex-biased abundance (

Table 4). Sixteen KOs exhibited positive log₂ fold-change (male enrichment), while five were female-enriched (negative log₂FC). The most pronounced male-biased functions included K00294 (ABC transporter; log₂FC = +1.54, p = 0.018) and K06247 (glutathione S-transferase; log₂FC = +1.20, p = 0.013). Female-biased KOs of greatest magnitude were K03286 (transaldolase; log₂FC = –7.55, p = 0.021) and K00558 (alanine dehydrogenase; log₂FC = –2.38, p = 0.022).

Figure 4 presents a volcano plot of –log₁₀(raw p) versus log₂ fold-change, with blue points denoting male-enriched and red points denoting female-enriched KOs above the nominal p = 0.05 line. Although no KO survives multiple-testing correction, these 21 candidates merit targeted validation in larger cohorts to confirm subtle sex-specific microbial functional differences.

3.4. Pathway Reconstruction

Figure 5 shows the top 20 KEGG pathways ranked by the total number of matched KOs across male and female samples. The most abundant pathway was Metabolic pathways, followed by Oxidative phosphorylation, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease. Neurodegenerative-disease modules (e.g., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, prion disease) appear within the top 20 but contribute relatively modest counts compared with core metabolic routes. Both sexes contribute to these mappings, with males generally showing higher KO counts in nearly every pathway, indicating a richer functional potential overall.

In the differential analysis, we identified a core set of 21 KOs whose abundances varied significantly by sex (FDR < 0.05), with 17 enriched in males and 5 enriched in females. When these sex-biased KOs were mapped back onto KEGG pathways (

Figure 6), “Metabolic pathways” remained dominant in both groups, though males contributed the bulk of matched KOs. Conversely, cancer-related modules such as “Pathways in cancer” and “MicroRNAs in cancer” were driven almost entirely by male-enriched KOs, suggesting a male-skewed enrichment of transporters and enzymes overlapping oncogenic networks. The female-enriched set featured only a few uniquely represented pathways—most notably “Cysteine and methionine metabolism”—hinting at a potential sex-specific signature in sulfur amino acid processing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

In this investigation, we employed a comprehensive metagenomic approach—encompassing deep shotgun sequencing, KO mapping, α- and β-diversity analyses, differential abundance testing, and pathway reconstruction—to delineate sex-specific functional characteristics within the gut microbiomes of Alzheimer’s-prone BXD mice. Our findings yield three key insights: a largely conserved core functional repertoire shared between male and female microbiomes; increased inter-individual functional heterogeneity in female samples; and subtle yet biologically relevant sex-biased enrichments in detoxification, central carbon metabolism, and amino-acid interconversion pathways. These observations enhance our understanding of sex as a determinant of gut microbial function in neurodegenerative contexts and formulate testable hypotheses for subsequent mechanistic inquiries.

4.2. Conserved Core Functional Repertoire

Across ten AD-BXD samples, sequencing depth (6.4–9.3 million paired reads per sample) and KO mapping efficiency (3.2–7.9% reads assigned to KOs;

Table 2) were consistent, ensuring comparable detection sensitivity between sexes. Heatmap analysis of the top 20 most abundant KOs (

Figure 2) and PCoA of Bray–Curtis distances (

Figure 3) demonstrated that both male and female samples cluster within a shared functional “cloud.” Core KOs—such as K02355 (acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase), K02256 (pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase), and K01534 (phosphoglycerate kinase)—were uniformly high in abundance, reflecting fundamental microbial roles in carbon utilization, energy generation, and nutrient transport (Sharon et al., 2016). The prominence of central carbon metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation pathways in pathway reconstructions (

Figure 5) underscores the microbiome’s conserved capacity to support host metabolic demands, potentially including production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that modulate neuronal health (Wang & Kasper, 2013).

The absence of distinct male-only or female-only clusters in β-diversity space suggests that sex per se does not globally reshape the gut-microbiome functional landscape. Rather, sex-dependent differences emerge as modulations within this shared core, manifesting in the relative weighting of specific pathways and enzymes. Such findings align with previous work indicating that, in healthy rodents, male and female gut microbiomes share a stable functional backbone but differ in particular enzymatic capacities, often driven by host hormonal milieu (Mueller et al., 2006).

4.3. Functional Diversity and Sex-specific Heterogeneity

Alpha diversity of KO profiles—quantified by the Shannon index—ranged from 2.79 to 4.17 in females versus 3.25 to 3.53 in males (

Table 3). On average, female samples exhibited a broader span of diversity values, with two extremes: a low-diversity sample (female_GT19-00151, Shannon = 2.79) dominated by a few high-abundance KOs, and a high-diversity sample (female_GT19-00304, Shannon = 4.17) marked by a more even KO distribution. Male samples, in contrast, clustered tightly in the midrange of diversity, suggesting consistent functional richness and evenness across individuals.

This greater heterogeneity in female functional complexity may reflect sex-specific influences such as fluctuating hormone levels, immunological differences, or disparate responses to environmental factors (e.g., diet, stress) that disproportionately affect female gut communities (Mueller et al., 2006). In neurodegenerative models, such variability could translate to divergent microbe-host crosstalk trajectories: certain female mice may harbor microbiomes more prone to produce neuroprotective metabolites (e.g., butyrate), whereas others may skew toward inflammatory outputs. Indeed, the female outlier (female_GT19-00304) that clustered separately in PCoA space (

Figure 3) exhibited both high Shannon diversity and unique KO patterns, underscoring the need to consider individual-level variation, especially in female cohorts, when designing microbiome interventions or stratified analyses.

4.4. Sex-biased Functional Enrichments

While FDR-corrected differential testing yielded no statistically significant hits, likely a consequence of moderate sample size and multiple-testing burden, we adopted a nominal p < .05 threshold to nominate 21 KOs with potential sex biases (

Table 4,

Figure 4). These KOs coalesce into three categories: detoxification & oxidative stress, central carbon metabolism, and amino-acid/nitrogen metabolism.

- 1.

Detoxification & Oxidative Stress

Two KOs were significantly enriched in male AD-BXD gut microbiomes: K06247 (glutathione S-transferase; log₂FC = +1.20, p = 0.013) and K02343 (ABC transporter substrate-binding protein; log₂FC = +1.19, p = 0.04). The co-enrichment of these functions suggests an enhanced microbial detoxification capacity in males, which may shift both luminal and systemic oxidative balance. Such alterations could attenuate ROS-driven neuroinflammatory processes implicated in Alzheimer’s pathology (Wang & Kasper, 2013), pointing to a sex-specific microbial contribution to host redox homeostasis and disease progression.

- 2.

Central Carbon Metabolism

Key male-biased KOs included K00294 (glycerol kinase; log₂FC = +1.54, p = 0.02), K00010 (glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; log₂FC > +0.50, p < 0.05), and the TCA-cycle enzyme K00020 (citrate synthase; log₂FC > +0.50, p < 0.05), whereas the female-biased enrichment of K03286 (transaldolase; log₂FC = –7.55, p = 0.02) indicates a shift toward the non-oxidative branch of the pentose-phosphate pathway. This sex-dependent partitioning of carbon flux, favoring glycolysis and TCA activity in males versus PPP shunting in females, may lead to divergent profiles of microbial metabolites, such as acetate versus propionate, and differential NADPH production. Such metabolic differentiation has the potential to modulate gut barrier integrity and neuroimmune signaling in a sex-specific manner (Takahashi, 2021).

- 3.

Amino-acid and Nitrogen Metabolism

The most pronounced female-biased KO was K00558 (alanine dehydrogenase; log₂FC = –2.38, p = .022), an enzyme interconverting alanine and pyruvate. Alterations in alanine cycling may influence luminal pools of branched-chain amino acids and neurotransmitter precursors (e.g., glutamate), potentially shaping host neurotransmission and mood regulation, both relevant to Alzheimer’s-associated behavioral phenotypes (Niciu et al., 2011).

4.5. Hypotheses for Future Research

From these nominally significant enrichments, we propose three mechanistic hypotheses for experimental validation:

- 1.

Detoxification & Oxidative Stress Hypothesis

Male-enriched KOs K06247 (glutathione S-transferase) and K02343 (ABC transporter substrate-binding protein) suggest that the gut microbiomes of male AD-BXD mice possess an elevated capacity for conjugating and exporting reactive species. We hypothesize that this enhanced microbial detoxification machinery in males contributes to more efficient clearance of oxidative stressors and xenobiotic compounds in the gut. Such a sex-specific functional signature could modulate systemic and neuroinflammatory trajectories, potentially influencing Alzheimer’s-like pathology via altered host–microbe redox interactions.

- 2.

Central Carbon Partitioning Hypothesis

The differential abundance analysis revealed a male bias in glycolytic and TCA-cycle enzymes—such as K00294 (glycerol kinase), K00010 (glucose-6-phosphate isomerase), and K00020 (citrate synthase)—contrasted by a strong female enrichment of K03286 (transaldolase) in the non-oxidative branch of the pentose-phosphate pathway. This pattern indicates that male microbiomes may preferentially channel substrates through energy-yielding glycolysis and TCA flux, whereas female microbiomes might divert carbon toward NADPH-generating PPP reactions. We hypothesize that these sex-dependent resource-processing strategies alter the profile of microbial metabolites, such as SCFAs and reducing equivalents, thereby impacting gut barrier function, immune modulation, and gut–brain signaling in distinct ways for males and females.

- 3.

Amino-acid Interconversion Hypothesis

Female-biased abundance of K00558 (alanine dehydrogenase) points to an increased microbial capacity for interconverting alanine and pyruvate, a key step linking nitrogen metabolism to central carbon pathways (Song et al., 2021). By shifting amino-acid pools, female AD-BXD microbiomes may influence the availability of precursors for host neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate) and modulators of nitrogen balance. We hypothesize that this enrichment leads to sex-specific differences in gut-derived amino acids, which could affect neural signaling, cognitive function, or mood regulation in Alzheimer’s-prone mice.

4.6. Integration with Pathway Reconstruction

Pathway mapping of these sex-biased KOs (

Figure 6) reinforces their biological coherence: male enrichments concentrate in “Pathways in cancer” and “MicroRNAs in cancer,” reflecting transporter and stress-response functions co-opted in oncogenic contexts, whereas female enrichments map to “Cysteine and methionine metabolism,” central to glutathione synthesis and methylation capacity. The link between pathways for short-chain fatty acids and sulfur-based amino acids suggests a connection between cellular balance and compounds from microbes that might influence how neurons express genes and respond to amyloid toxicity.

4.7. Limitations

The study acknowledges several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the relatively small cohort of five male and five female mice may reduce the statistical power necessary to detect subtle sex-specific differences in gut microbiome functions. Second, by focusing on a single time point, the analysis may not capture the temporal dynamics of microbial community composition and function throughout Alzheimer’s disease progression. Finally, although the iMGMC pipeline provides an integrated workflow—from host-read removal through KO and gene quantification—it was developed using standard mouse-gut metagenomes and has not been specifically optimized for the AD-BXD model, which introduces additional caveats.

One key concern is reference bias and host-removal efficiency. The pipeline relies on the mm10 reference genome for subtracting host reads; any divergence between the BXD strain’s genome and mm10 could result in incomplete host read removal or, alternatively, the inadvertent exclusion of legitimate microbial sequences. Furthermore, the KO catalog underpinning functional annotation was constructed from publicly available mouse-gut metagenomes. Given the unique genetic and metabolic milieu of AD-BXD mice, especially under neurodegenerative conditions, strain-specific genes or low-frequency variants may be underrepresented, leading to incomplete annotation of relevant functions. Coupled with marginal per-sample sequencing depths, these factors may bias the analysis toward high-abundance, broadly conserved metabolic pathways, while under-sampling scarcer, potentially disease-relevant KOs.

Additionally, there is a lack of benchmarking data for iMGMC within Alzheimer’s or BXD contexts, raising uncertainty about error rates in trimming, decontamination, and alignment steps under these specialized conditions. Without cross-validation against alternative pipelines, results may reflect pipeline-specific artifacts rather than true biological signals. Reliance on a single analytical framework limits the ability to triangulate findings, particularly for poorly characterized KOs or novel microbial functions that could be critical to understanding gut–brain interactions in this model. Future work should incorporate longitudinal sampling, deeper sequencing, and comparative validation using complementary bioinformatics workflows to mitigate these limitations.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we applied a comprehensive metagenomic and data-analytics pipeline to compare gut-microbiome functional potentials in male and female AD-BXD mice. Consistent sequencing depth and KO-mapping rates across ten samples supported robust comparisons, while heatmap and PCoA analyses revealed a shared core of central-carbon and energy-metabolism functions with nuanced sex-dependent variations. Female samples exhibited greater inter-individual Shannon diversity, suggesting more heterogeneous functional landscapes, whereas male samples showed nominal enrichment in detoxification (glutathione S-transferase, ABC transporter) and central-carbon (glycolysis/TCA) KOs, and females in amino-acid interconversion (alanine dehydrogenase) and PPP enzymes (transaldolase).

Building on these insights, we propose three testable, data-driven hypotheses: (1) detoxification-related KO abundances can classify mouse sex with high accuracy; (2) a composite central-carbon index correlates with neuropathological or behavioral measures; and (3) network analysis will uncover sex-specific amino-acid metabolism modules. Integrating pathway-level scores into statistical and machine-learning models transforms descriptive profiles into predictive features, paving the way for larger, longitudinal, and multi-omics studies to validate causal links between sex-biased microbial functions and Alzheimer’s-like phenotypes.

Data Availability

The raw sequence reads (FASTQ files) used in this study are publicly available in the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (Synapse ID: syn17016211;

https://doi.org/10.7303/syn17016211). Should data in other formats be required, the author is available to provide them upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. PubMed, 28(2), 203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25830558.

- Chakrabarti, A., Geurts, L., Hoyles, L., Iozzo, P., Kraneveld, A. D., Fata, G. L., Miani, M., Patterson, E., Pot, B., Shortt, C., & Vauzour, D. (2022). The microbiota–gut–brain axis: pathways to better brain health. Perspectives on what we know, what we need to investigate and how to put knowledge into practice [Review of The microbiota–gut–brain axis: pathways to better brain health. Perspectives on what we know, what we need to investigate and how to put knowledge into practice]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 79(2). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Dennison, J., Ricciardi, N., Lohse, I., Volmar, C., & Wahlestedt, C. (2021). Sexual Dimorphism in the 3xTg-AD Mouse Model and Its Impact on Pre-Clinical Research [Review of Sexual Dimorphism in the 3xTg-AD Mouse Model and Its Impact on Pre-Clinical Research]. Journal of Alzheimer s Disease, 80(1), 41. IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J., Jin, Z., Yang, X., Lou, J., Shan, W., Hu, Y., Du, Q., Liao, Q., Xie, R., & Xu, J. (2020). Role of gut microbiota via the gut-liver-brain axis in digestive diseases [Review of Role of gut microbiota via the gut-liver-brain axis in digestive diseases]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 26(40), 6141. Baishideng Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J. D., Bernstein, Ç. N., Tremlett, H., Domselaar, G. V., & Knox, N. (2019). A Fungal World: Could the Gut Mycobiome Be Involved in Neurological Disease? [Review of A Fungal World: Could the Gut Mycobiome Be Involved in Neurological Disease?]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9. Frontiers Media. [CrossRef]

- Han, K., Ji, L., Wang, C., Shao, Y., Chen, C., Liu, L., Feng, M., Yang, F., Wu, X., Li, X., Xie, Q., He, L., Shi, Y., He, G., Dong, Z., & Yu, T. (2023). The host genetics affects gut microbiome diversity in Chinese depressed patients. Frontiers in Genetics, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, M., Indari, O., Baral, B., Jakhmola, S., Tiwari, D., Bhandari, V., Pandey, R. K., Bala, K., Sonawane, A., & Jha, H. C. (2022). Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota from the Perspective of the Gut–Brain Axis: Role in the Provocation of Neurological Disorders [Review of Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota from the Perspective of the Gut–Brain Axis: Role in the Provocation of Neurological Disorders]. Metabolites, 12(11), 1064. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., & Sato, Y. (2019). KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Science, 29(1), 28. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., & Kawashima, M. (2021). KEGG mapping tools for uncovering hidden features in biological data. Protein Science, 31(1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Lesker, T. R., Durairaj, A. C., Gálvez, E. J. C., Lagkouvardos, I., Baines, J. F., Clavel, T., Sczyrba, A., McHardy, A. C., & Strowig, T. (2020). An Integrated Metagenome Catalog Reveals New Insights into the Murine Gut Microbiome. Cell Reports, 30(9), 2909. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C. R., Osadchiy, V., Kalani, A., & Mayer, E. A. (2018). The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis [Review of The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis]. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 6(2), 133. Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S., Saunier, K., Hanisch, C., Norin, E., Alm, L., Midtvedt, T., Cresci, A., Silvi, S., Orpianesi, C., Verdenelli, M. C., Clavel, T., Koebnick, C., Zunft, H. F., Doré, J., & Blaut, M. (2006). Differences in Fecal Microbiota in Different European Study Populations in Relation to Age, Gender, and Country: a Cross-Sectional Study. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(2), 1027. [CrossRef]

- Neuner, S. M., Heuer, S. E., Huentelman, M. J., O’Connell, K. M. S., & Kaczorowski, C. C. (2018). Harnessing Genetic Complexity to Enhance Translatability of Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models: A Path toward Precision Medicine. Neuron, 101(3), 399. [CrossRef]

- Niciu, M. J., Kelmendi, B., & Sanacora, G. (2011). Overview of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the nervous system [Review of Overview of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the nervous system]. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 100(4), 656. Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Sharon, G., Sampson, T. R., Geschwind, D. H., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2016). The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome [Review of The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome]. Cell, 167(4), 915. Cell Press. [CrossRef]

- Song, M., Yuan, F., Li, X., Ma, X., Yin, X., Rouchka, E. C., Zhang, X., Deng, Z., Prough, R. A., & McClain, C. J. (2021). Analysis of sex differences in dietary copper-fructose interaction-induced alterations of gut microbial activity in relation to hepatic steatosis. Biology of Sex Differences, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. (2021). Neuroprotective Function of High Glycolytic Activity in Astrocytes: Common Roles in Stroke and Neurodegenerative Diseases [Review of Neuroprotective Function of High Glycolytic Activity in Astrocytes: Common Roles in Stroke and Neurodegenerative Diseases]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(12), 6568. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Wang, Y. (2016). Gut Microbiota-brain Axis [Review of Gut Microbiota-brain Axis]. Chinese Medical Journal, 129(19), 2373. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Kasper, L. H. (2013). The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders [Review of The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders]. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 38, 1. Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, H. U., Kaleta, C., Cossais, F., Schaeffer, E., Berndt, H., Best, L., Dost, T., Glüsing, S., Groussin, M., Poyet, M., Heinzel, S., Bang, C., Siebert, L., Demetrowitsch, T., Leypoldt, F., Adelung, R., Bartsch, T., Bosy-Westphal, A., Schwarz, K., & Berg, D. (2022). Microbiome and metabolome insights into the role of the gastrointestinal-brain axis in neurodegenerative diseases: unveiling potential therapeutic targets. arXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P., Zeng, B., Zhou, C., Liu, M., Fang, Z., Xu, X., Zeng, L., Chen, J., Fan, S., Du, X., Zhang, X., Yang, D., Yang, Y., Meng, H., Li, W., Melgiri, N. D., Licinio, J., Wei, H., & Xie, P. (2016). Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(6), 786. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M. Z., Peng, T., Duarte, M. L., Wang, M., & Cai, D. (2024). Updates on mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease [Review of Updates on mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease]. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 19(1). BioMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Han, Y., Du, J., Liu, R., Jin, K., & Yi, W. (2017). Microbiota-gut-brain axis and the central nervous system [Review of Microbiota-gut-brain axis and the central nervous system]. Oncotarget, 8(32), 53829. Impact Journals LLC. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).