Submitted:

27 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

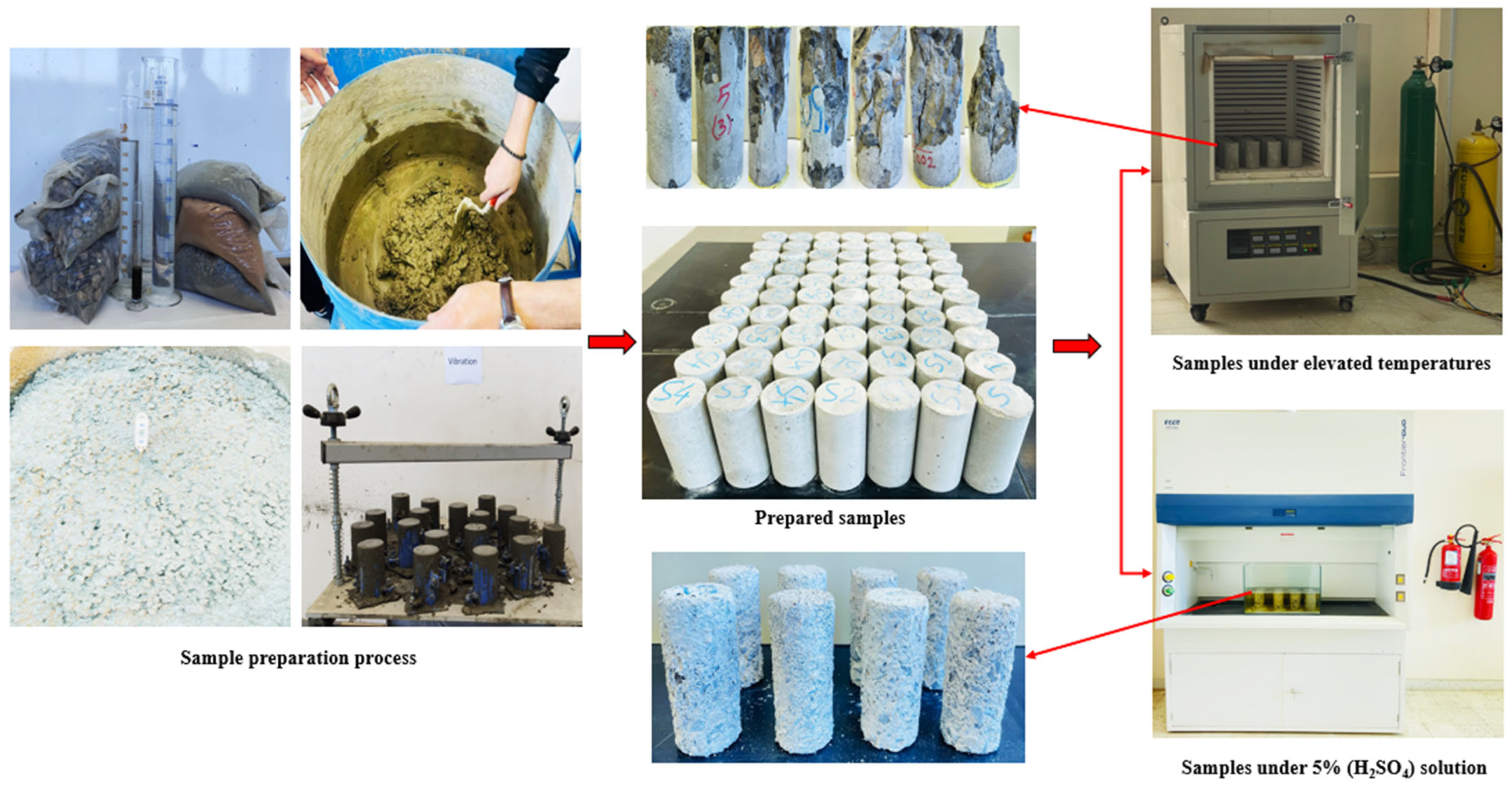

2. Experimental Methodologies of the Study

2.1. Preparation Methodology of Different Sand Types

2.2. Engineering Properties of Prepared Sand Combinations

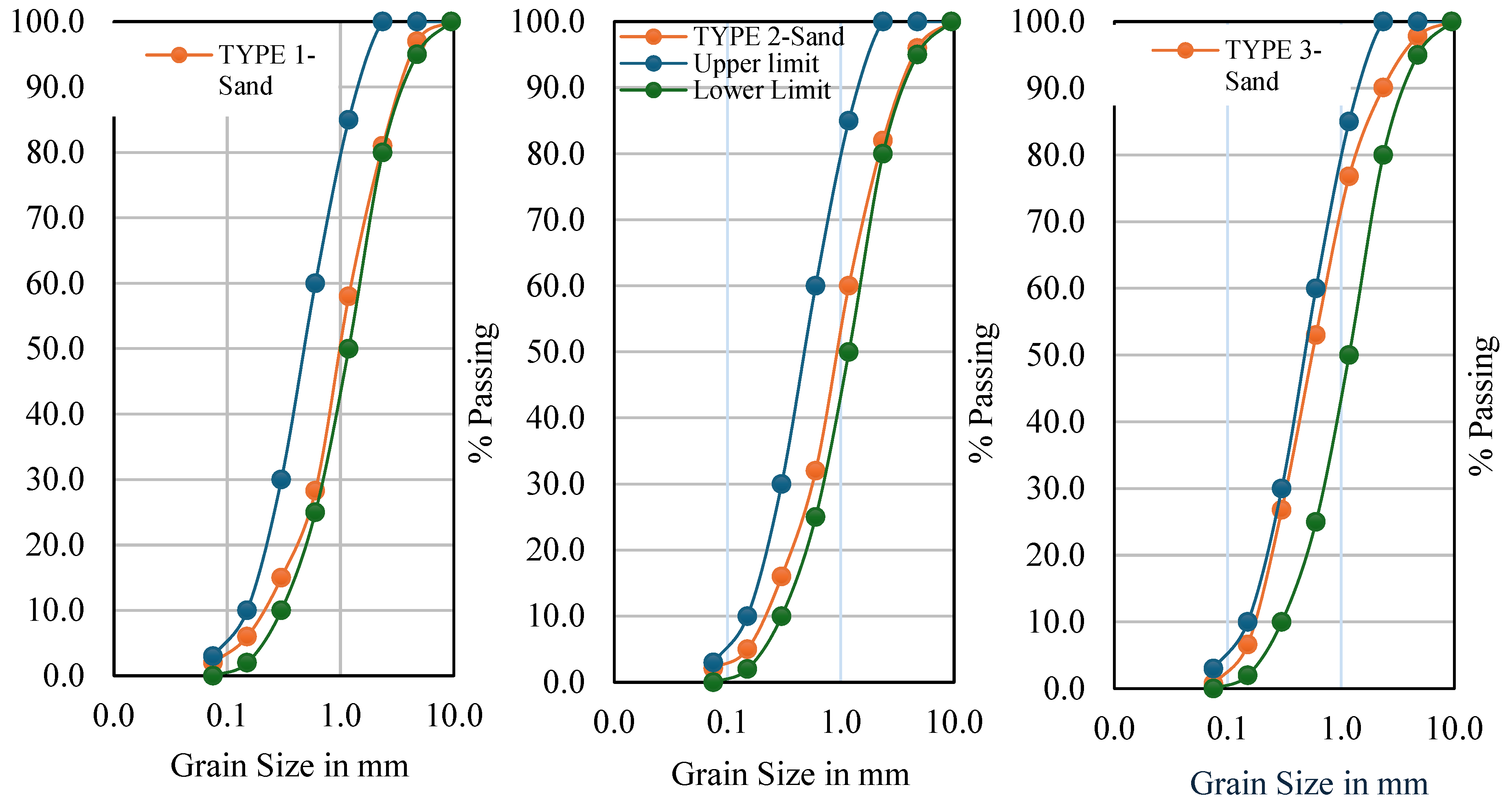

2.2.1. Gradation Curves of Prepared Sand Combinations

2.2.2. Physical Parameters of Concrete Mix Design

2.3. Design Mix Ingredients and Sample Preparation

2.4. Muffle Furnace

3. Discussion on the Results of the Study

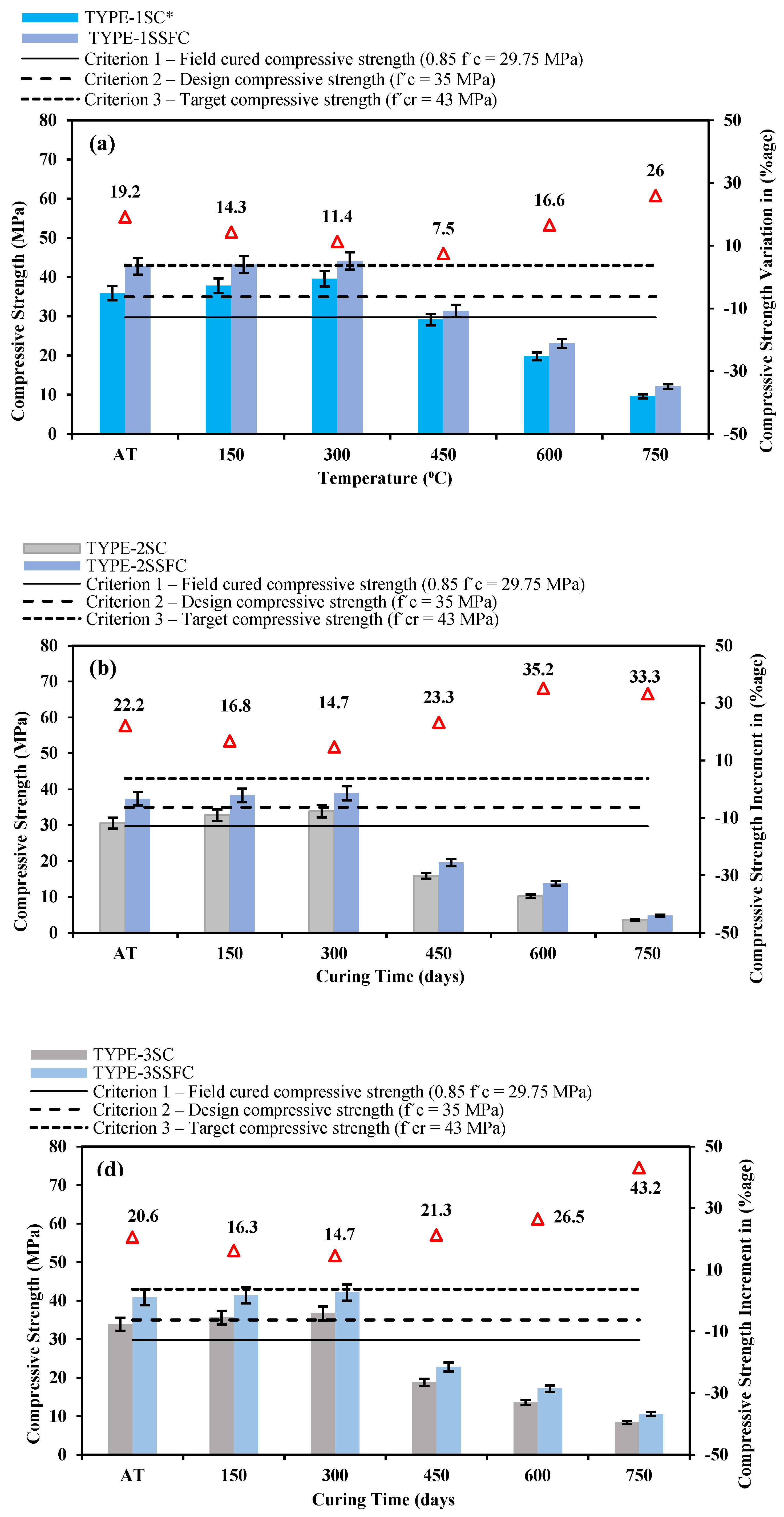

3.1. High Temperature Performance of Newly Developed Concrete

3.1.1. Deterioration of the Samples Under Compressive Strength

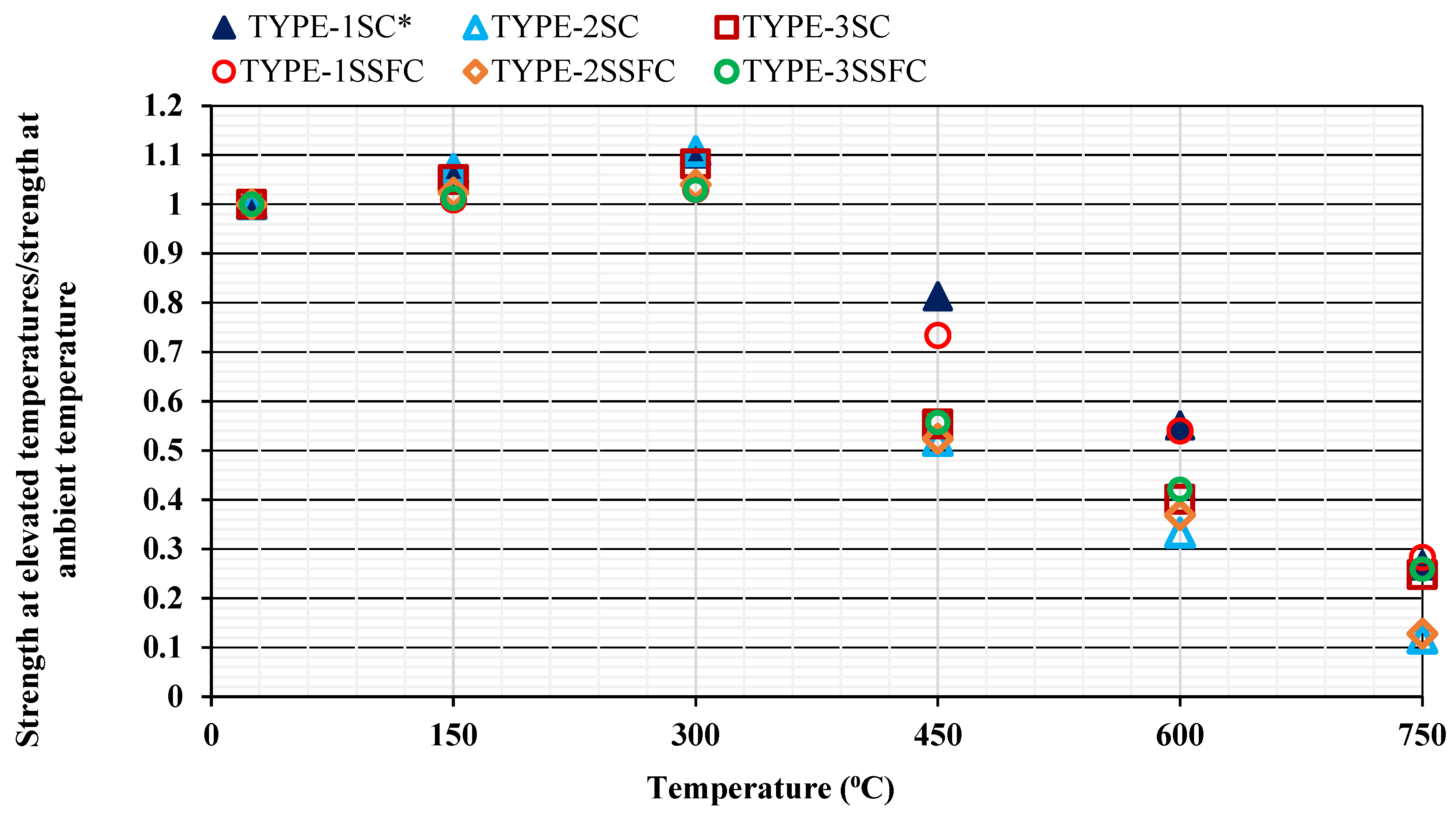

3.1.2. Deterioration of the Samples Under Residual Compressive Strength

3.2. Performance of the Developed sand Concrete Against Sulphuric Acid

3.2.1. Sulphuric Acid Attack on Prepared Mixes of this Study

3.2.2. Deterioration of Hardened Concrete by Mass

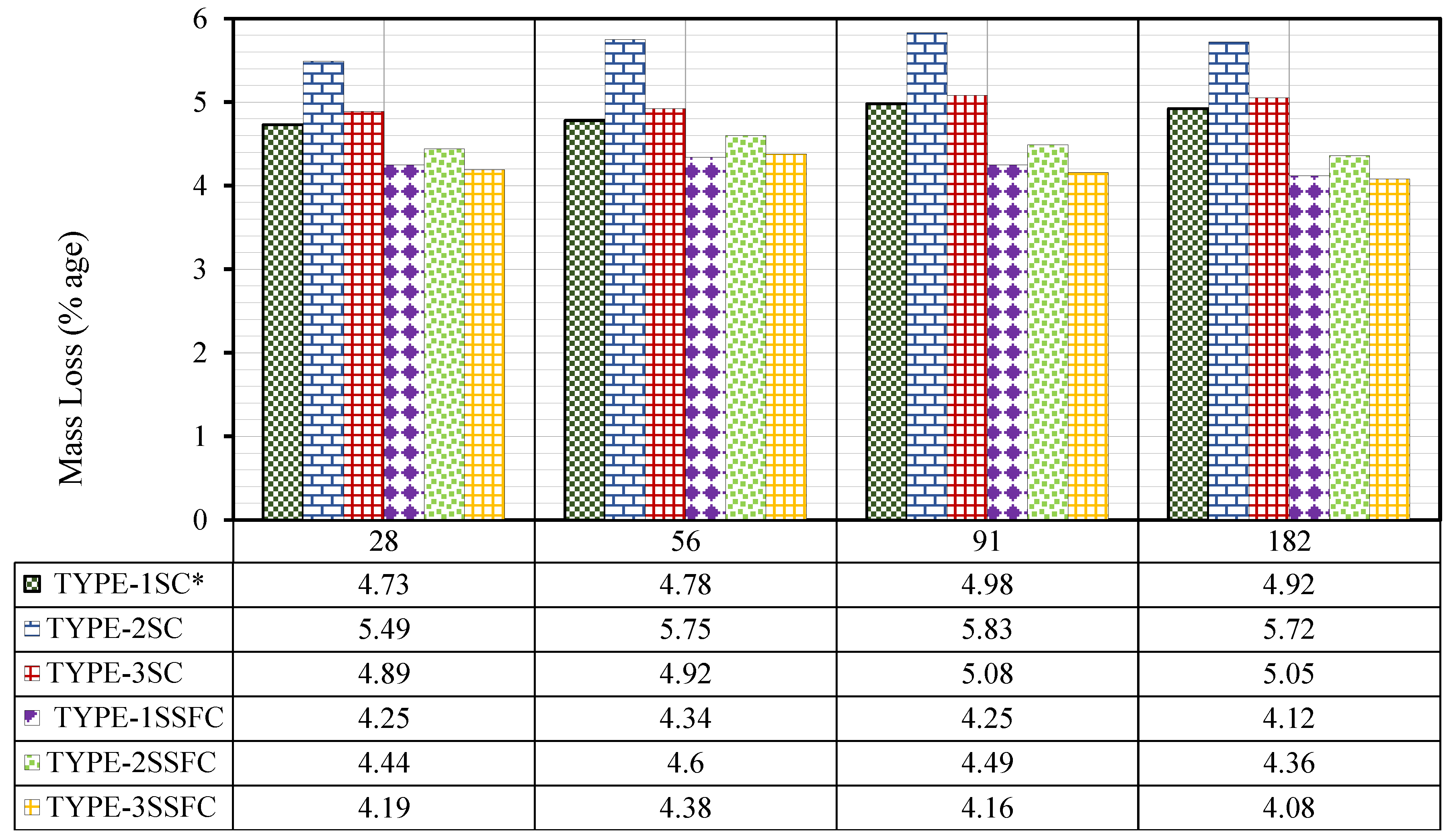

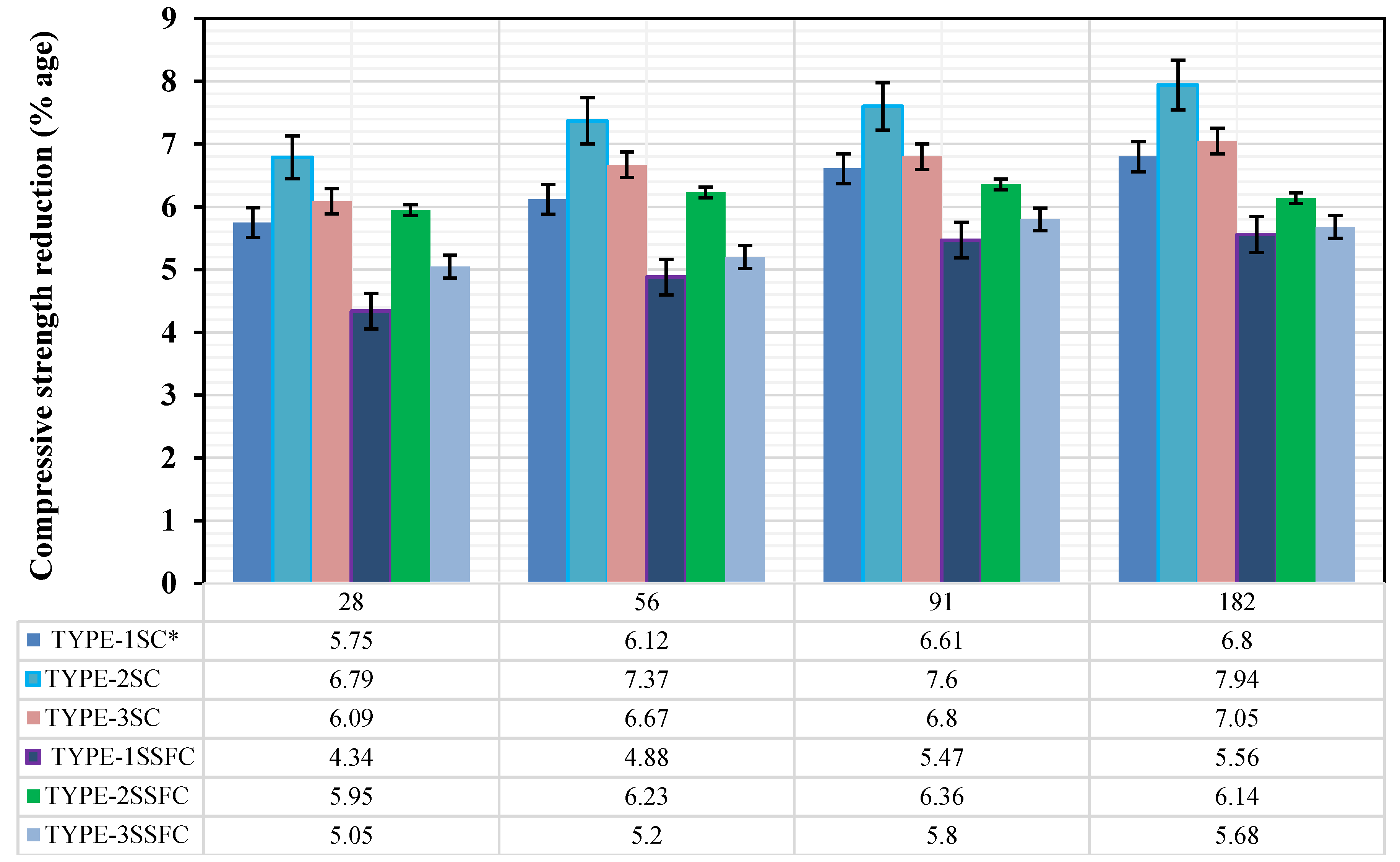

3.2.3. Deterioration of Hardened Concrete by Strength

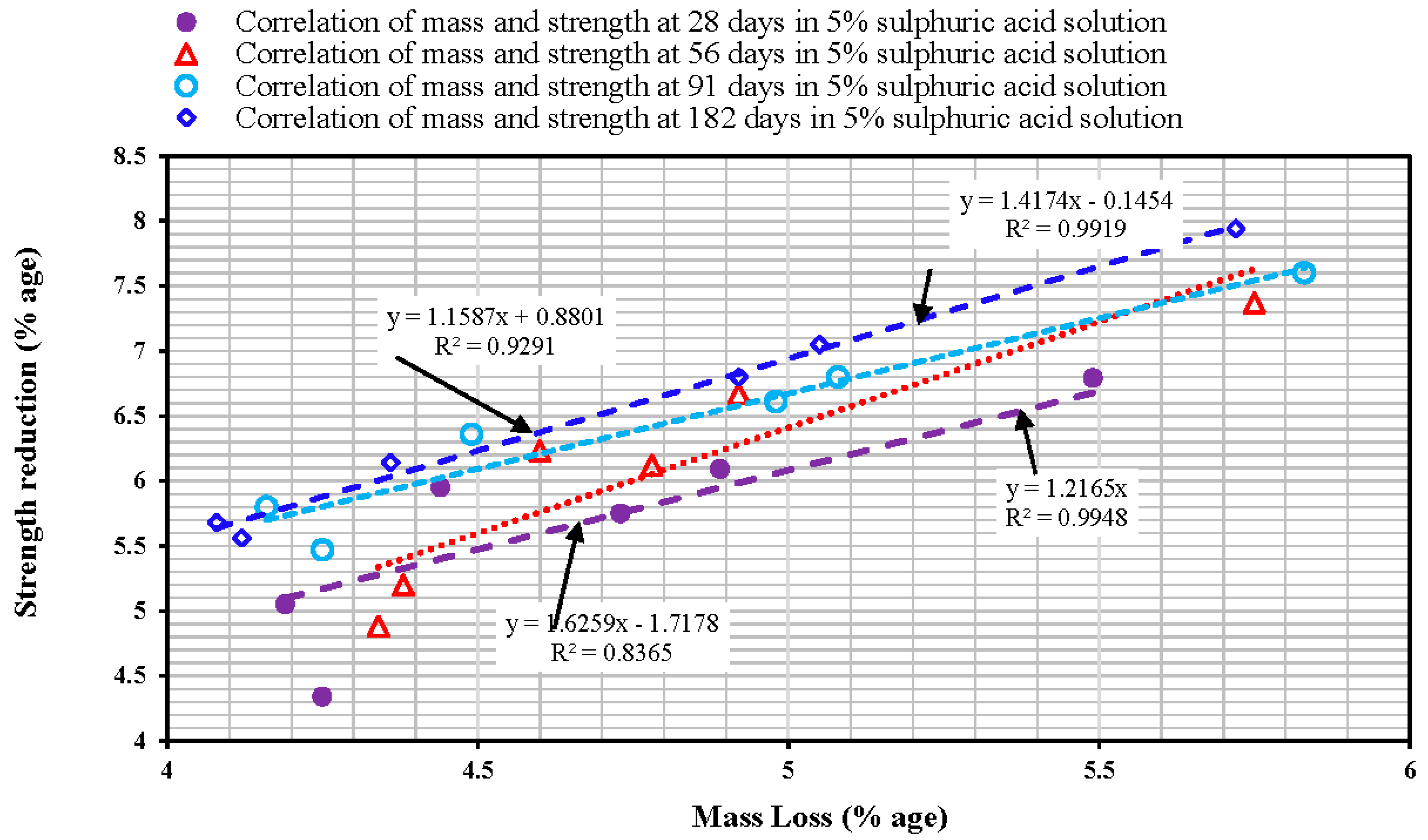

3.2.4. Correlation Between Mass Loss and Strength Reduction

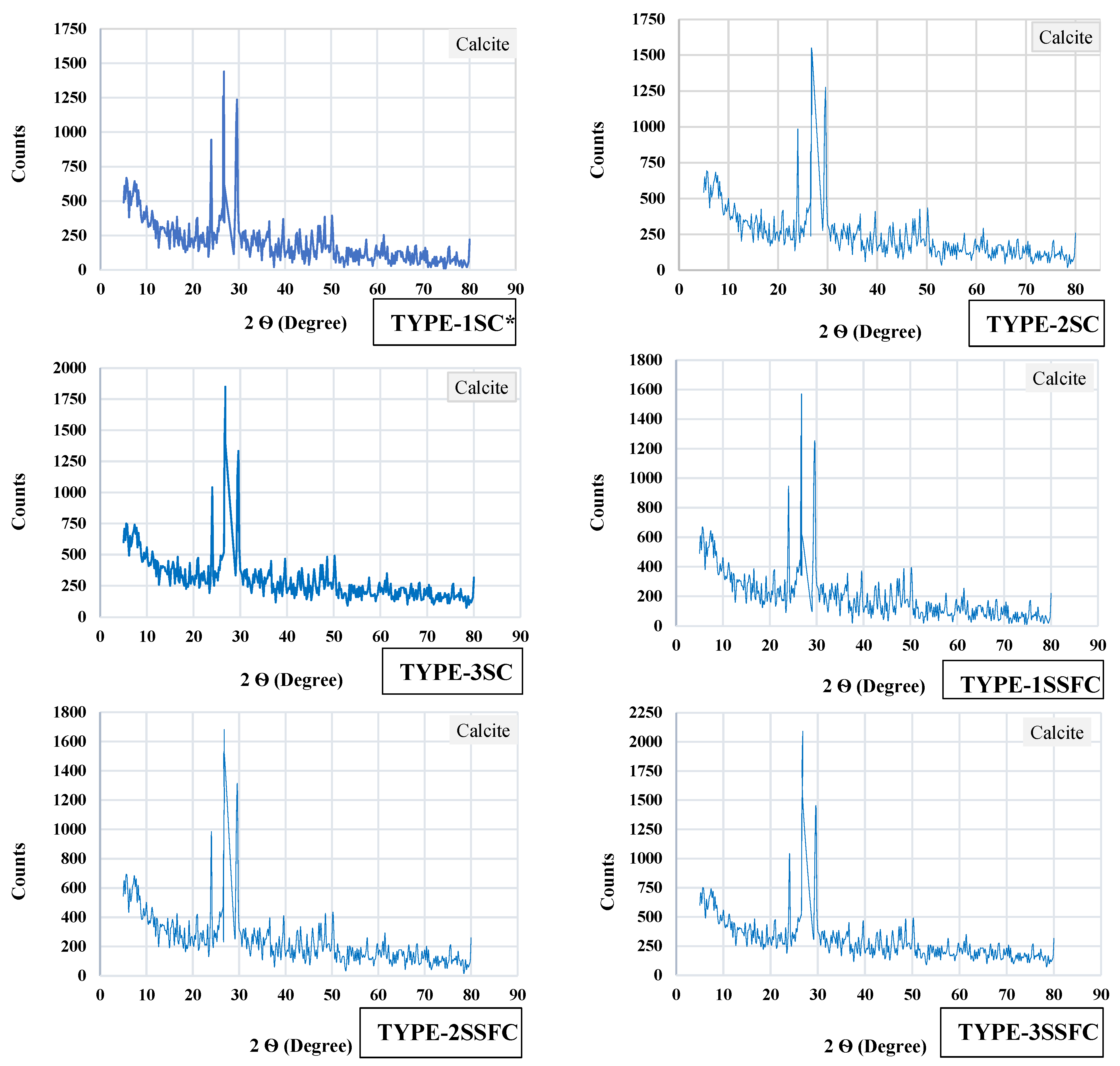

4. Morphology of Sustainable Concrete Made by the Different Sand Combinations

4. Scope and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

- It is concluded from the results of the study that newly developed sand concrete TYPE-1SSFC, TYPE-2SSFC, and TYPE-3SSFC with the optimized 10% silica fume showed less deterioration in the samples at each heating stage (150-750°C) compared to the mixes TYPE-1SC*, TYPE-2SC, and TYPE-3SC without silica fume content.

- It is also concluded that the sustainable design mix TYPE-3SSFC with the sand combination (50% recycled sand + 45% desert sand + 5% crumb rubber) performed better than the mix TYPE-2SSFC (100% recycled sand). The rate of strength change at each temperature range in the mix TYPE-3SSFC is less than that of TYPE-2SSFC. It could be because the crumb rubber has high thermal resistance.

- It has been concluded from the analysis of the results that the maximum deterioration was reported in the first 28 days when the samples were immersed in a (5% H2SO4 solution). The chemical reaction in the early days was fast because H2SO4 reacted with Ca(OH)2, gypsum precipitated in the solution, and the particles from the samples were removed, which was the reason for reducing the samples' mass. This pattern was similar in all mixes up to 28 days of immersion. A slight variation in mass increment was observed at 56 and 91 days later. This phenomenon was about to be neutralized when the immersion period reached 182 days.

- A linear correlation coefficient of mass loss for compressive strength reduction was obtained with the duration of immersion. It can be found from the results that the value increased as the duration of samples increased, and the highest value was reported at 182 days of immersion period . As and when the duration was increased beyond 28 days, the variation in pH was reported, and the neutralization reaction slowed down. A slight variation in mass increment was observed at 56 and 91 days later. This phenomenon would be neutralized when the immersion period reached about 182 days.

- The microstructural investigation (SEM-EDS) in the prepared concrete with TYPE 3-Sand combination shows the establishment of CSH gel and calcite crystals, which solidify into a solid mass, creating a more compact and solid matrix microstructure. It was due to the availability of calcite precipitations in recycled sand and silica fume in the mix. Hence, it concluded that it was crucial to stabilize the solid matrix structure, which ensured better stability against high thermal resistance and acid attacks.

- The mix with sustainable TYPE 3-Sand combination (50% recycled sand + 45% desert sand + 5% crumb rubber) performed almost the same as the reference mix with all natural materials. The mix with TYPE 2-Sand (100% recycled sand) revealed inferior results, low stability, and high damage. Thus, 100% recycled sand is not recommended for structural concrete. Finally, it has been concluded that the developed TYPE 3-Sand with optimized 10% silica fume content showed better resistance against high temperatures and (5% H2SO4 solution).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. Fischer, M. Werge, and A. Reichel, "EU as a Recycling Society," European Topic Centre on Resource Waste Management, Working Paper 2/2009, 2009.

- P. V. Sáez, M. Merino, and C. Porras-Amores, "Managing construction and demolition (C&D) waste–a European perspective," in International Conference on Petroleum and Sustainable Development, 2011, vol. 26, pp. 27-31.

- L. Arpitha, Z. Fathima, G. Dhanyashree, and R. Yeshaswini, "Construction & demolition waste: Overview, insights, management, reviews and its future," Smart Cities and Sustainable Manufacturing, pp. 275-293, 2025.

- M. N. Akhtar, M. Jameel, Z. Ibrahim, and N. M. Bunnori, "Incorporation of recycled aggregates and silica fume in concrete: an environmental savior-a systematic review," Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2022.

- V. Monier, S. Mudgal, M. Hestin, M. Trarieux, and S. Mimid, "Service contract on management of construction and Demolition Waste–SR1," Final Report Task, vol. 2, p. 240, 2011.

- O. Ouda, H. Peterson, M. Rehan, Y. Sadef, J. Alghazo, and A. Nizami, "A case study of sustainable construction waste management in Saudi Arabia," Waste and Biomass Valorization, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 2541-2555, 2018.

- M. Mawed, M. S. Al Nuaimi, and G. Kashawni, "Construction and demolition waste management in the uae: Application and obstacles," GEOMATE Journal, vol. 18, no. 70, pp. 235-245, 2020.

- A.-S. Nizam, M. Rehan, I. M. Ismail, T. Almeelbi, and O. Ouda, "Waste Biorefinery in Makkah: A Solution to Convert Waste produced during Hajj and Umrah Seasons into Wealth. pdf," 2015.

- A.-S. Nizami et al., "Waste biorefineries: enabling circular economies in developing countries," Bioresource technology, vol. 241, pp. 1101-1117, 2017.

- A. Nizami et al., "An argument for developing waste-to-energy technologies in Saudi Arabia," Chemical Engineering Transactions, vol. 45, pp. 337-342, 2015.

- A. Alzaydi, "Recycling Potential of Construction and Demolition Waste in GCC Countries," presented at the Scientific Forum in the Recycling of Municipal Solid Waste, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2014.

- S. Kabir, Al-Ismaeel, A.A., Bu Aeshah, A.Y., Al-Sadun, F.S, "Sustainable management program for construction waste," presented at the 9th International Concrete Conference & Exhibition, Manama, 2013.

- S. Nazar, " Recycle construction waste, save mountains: activist.," Accessed on 20 Aug 2017 2010.

- A. M. Halahla, M. Akhtar, and A. H. Almasri, "Utilization of demolished waste as coarse aggregate in concrete," Civil Engineering Journal, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 540-551, 2019.

- L. Koehnken and M. Rintoul, "Impacts of Sand Mining on Ecosystem Structure," Process & Biodiversity in Rivers WWF, Swiss, 2018.

- M. Bendixen, J. Best, C. Hackney, and L. L. Iversen, "Time is running out for sand," ed: Nature Publishing Group, 2019.

- J. Best, "Anthropogenic stresses on the world’s big rivers," Nature Geoscience, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 7-21, 2019.

- M. N. Akhtar, A. Alotaibi, and N. I. Shbeeb, "River Sand Replacement with Sustainable Sand in Design Mix Concrete for the Construction Industry," Civil Engineering Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 201-214, 2025.

- L. Koehnken and M. Rintoul, "Impacts of sand mining on ecosystem structure, process and biodiversity in rivers," World Wildlife Fund International, vol. 159, 2018.

- L. Gallagher and P. Peduzzi, "Sand and sustainability: Finding new solutions for environmental governance of global sand resources," 2019.

- M. N. Akhtar, K. A. Bani-Hani, D. A. H. Malkawi, and O. Albatayneh, "Suitability of sustainable sand for concrete manufacturing-A complete review of recycled and desert sand substitution," Results in Engineering, p. 102478, 2024.

- N. Bairagi, H. Vidyadhara, and K. Ravande, "Mix design procedure for recycled aggregate concrete," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 188-193, 1990.

- Y.-H. Lin, Y.-Y. Tyan, T.-P. Chang, and C.-Y. Chang, "An assessment of optimal mixture for concrete made with recycled concrete aggregates," Cement and concrete research, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 1373-1380, 2004.

- L. Evangelista and J. de Brito, "Mechanical behaviour of concrete made with fine recycled concrete aggregates," Cement and concrete composites, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 397-401, 2007.

- M. Guendouz, D. Boukhelkhal, L. Benatallah, S. Hamraoui, and M. Hadjadj, "Feasibility of recycling marble waste powder as fine aggregate in self-compacting sand concrete," Studies in Engineering and Exact Sciences, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. e13171-e13171, 2025.

- M. R. Rafi, S. Omary, A. Faqiri, and E. Ghorbel, "Recycling Marble Waste from Afghan Mining Sites as a Replacement for Cement and Sand," Buildings, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 164, 2025.

- G. Mahran, A. B. ElDeeb, M. M. Badawy, and A. I. Anan, "Enhanced mechanical properties of concrete using pre-treated rubber as partial replacement of fine aggregate," Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 1-14, 2025.

- T. Vieira, A. Alves, J. De Brito, J. Correia, and R. Silva, "Durability-related performance of concrete containing fine recycled aggregates from crushed bricks and sanitary ware," Materials & Design, vol. 90, pp. 767-776, 2016.

- D. CarroYLόpez, B. GonzálezYFonteboa, F. MartínezYAbella, I. GonzálezYTaboada, J. de Britob, and F. VarelaYPugaa, "Proportioning, microstructure and fresh properties of selfYcompacting concrete with recycled sand," Procedia engineering, vol. 171, pp. 645-657, 2017.

- E. Fernández-Ledesma, J. Jiménez, J. Ayuso, V. Corinaldesi, and F. Iglesias-Godino, "A proposal for the maximum use of recycled concrete sand in masonry mortar design," Materiales de Construcción, vol. 66, no. 321, p. 075, 2016.

- S. R. Sarhat and E. G. Sherwood, "Residual mechanical response of recycled aggregate concrete after exposure to elevated temperatures," Journal of materials in civil engineering, vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 1721-1730, 2013.

- H. Salahuddin, A. Nawaz, A. Maqsoom, and T. Mehmood, "Effects of elevated temperature on performance of recycled coarse aggregate concrete," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 202, pp. 415-425, 2019.

- Y.-c. Guo, J.-h. Zhang, G.-m. Chen, and Z.-h. Xie, "Compressive behaviour of concrete structures incorporating recycled concrete aggregates, rubber crumb and reinforced with steel fibre, subjected to elevated temperatures," Journal of cleaner production, vol. 72, pp. 193-203, 2014.

- ACI-211.1, "Standard practice for selecting proportions for normal, heavyweight, and mass concrete," in American Concrete Institute, 1991.

- ASTM-C136-06, "Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates," 2006.

- Standard practice for selecting proportions for normal, heavyweight, and mass concrete, ACI-211.1-91, Nov. 1, 1991 1991.

- ACI-318, "Building code requirements for structural concrete (ACI 318-08) and commentary," 2008: American Concrete Institute.

- A. C. Institute, "ACI 214R-11: Guide to evaluation of strength test results of concrete," 2011: American Concrete Institute.

- ASTM-C33, "C33,“Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates,” ASTM International, vol. i, no," ed: C, 2003.

- A. Standard, "ASTM-C127-07: Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density (Specific Gravity), and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate," Stand. test method Specif. gravity Absorpt, 2007.

- Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density (specific gravity), and Absorption of Fine Aggregates," ed, , ASTM-C128-88, 2001.

- Standard Test Method for Sand Equivalent Value of Soils and Fine Aggregate, ASTM-D-2419-74, 2014.

- C. ASTM, "Standard test method for bulk density (“unit weight”) and voids in aggregate," American Society for Testing and Materials, Annual Book: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- A. Fadiel, F. Al Rifaie, T. Abu-Lebdeh, and E. Fini, "Use of crumb rubber to improve thermal efficiency of cement-based materials," American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1-11, 2014.

- J.-C. Liu, K. H. Tan, and Y. Yao, "A new perspective on nature of fire-induced spalling in concrete," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 184, pp. 581-590, 2018.

- M. Adamu, Y. E. Ibrahim, and H. Alanazi, "Evaluating the Influence of Elevated Temperature on Compressive Strength of Date-Palm-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Using Response Surface Methodology," Materials, vol. 15, no. 22, p. 8129, 2022.

- M. N. Akhtar, Z. Ibrahim, N. M. Bunnori, M. Jameel, N. Tarannum, and J. Akhtar, "Performance of sustainable sand concrete at ambient and elevated temperature," ed: Elsevier, 2021.

- M. Khan, M. Cao, X. Chaopeng, and M. Ali, "Experimental and analytical study of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete prepared with basalt fiber under high temperature," Fire and Materials, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 205-226, 2022.

- A. Khodabakhshian, M. Ghalehnovi, J. De Brito, and E. A. Shamsabadi, "Durability performance of structural concrete containing silica fume and marble industry waste powder," Journal of cleaner production, vol. 170, pp. 42-60, 2018.

- B. S. Thomas, R. C. Gupta, and V. J. Panicker, "Recycling of waste tire rubber as aggregate in concrete: durability-related performance," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 112, pp. 504-513, 2016.

- E. Hewayde, M. L. Nehdi, E. Allouche, and G. Nakhla, "Using concrete admixtures for sulphuric acid resistance," Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Construction Materials, vol. 160, no. 1, pp. 25-35, 2007.

- A. Arivumangai, R. Narayanan, and T. Felixkala, "Study on sulfate resistance behaviour of granite sand as fine aggregate in concrete through material testing and XRD analysis," Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 43, pp. 1724-1729, 2021.

- V. S. Kashyap, G. Sancheti, J. S. Yadav, and U. Agrawal, "Smart sustainable concrete: enhancing the strength and durability with nano silica," Smart Construction and Sustainable Cities, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 20, 2023.

| Sand Designation | Manufactured and recycled sand | Desert sand | Crumb rubber | Total | ||

| Fraction | Fraction | Fraction | ||||

| (4.75-2.36) mm | (2.36-1.18) mm |

(1.18-0.075) mm |

(2.36-0.30) mm |

(1.18-0.150) mm |

||

| TYPE 1-Sand | 20% | 40% | 40% | - | - | 100% |

| TYPE 2-Sand | 20% | 40% | 40% | - | - | 100% |

| TYPE 3-Sand | 20% | 15% | 15% | 45% | 5% | 100% |

| Physical parameters | Values | Standard |

| Specified compressive strength (f´c) | 35 MPa | [37,38] |

| Required average compressive strength (f´cr) | 43 MPa | [37,38] |

| Required Slump | 75-100 mm | [36] |

| Maximum size of aggregate | 19 mm | [36] |

| Fineness Modulus (FM) of TYPE 1-Sand | 2.8 | [36] |

| Fineness Modulus (FM) of TYPE 2-Sand | 2.7 | [36] |

| Fineness Modulus (FM) of TYPE 3-Sand | 2.6 | [36] |

| Grading of aggregate as satisfied | Within upper and lower limits | [35,39] |

| The bulk specific gravity of natural coarse aggregate | 2.920 | [40] |

| The bulk specific gravity of TYPE 1-Sand | 2.808 | [41] |

| The bulk specific gravity of TYPE 2-Sand | 2.634 | [41] |

| The bulk specific gravity of TYPE 3-Sand | 2.746 | [41] |

| Sand equivalent value of TYPE 1-Sand | 95% | [42] |

| Sand equivalent value of TYPE 2-Sand | 92% | [42] |

| Sand equivalent value of TYPE 3-Sand | 89% | [42] |

| Rodded bulk density of coarse aggregate | 1598 kg/m3 | [43] |

| Absorption capacity of coarse aggregate | 0.88 | [40] |

| Absorption capacity of TYPE 1-Sand | 0.90 | [41] |

| Absorption capacity of TYPE 2-Sand | 6.429 | [41] |

| Absorption capacity of TYPE 3-Sand | 3.806 | [41] |

| Moisture content of fine and coarse aggregate | Zero | [36] |

| Exposure conditions | Normal | [36] |

|

Mix Designation |

Concrete component proportions | ||||||||||

| Cementitious materials | Combination of fine aggregates | Natural coarse aggregate |

OPC kg/m3 |

Water kg/m3 |

Admixture by weight of cement (%) |

Slump mm |

|||||

|

OPC (%) |

SF (%) |

MS (%) | RS (%) | DS (%) | CR (%) |

NCA % |

|||||

| TYPE-1SC* | 100 | 100 | - | - | - | 100 | 436 | 205 | 0.8 | 100 | |

| TYPE-2SC | 100 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 436 | 205 | 1.8 | 100 | ||

| TYPE-3SC | 100 | 50 | 45 | 5 | 100 | 436 | 205 | 1.3 | 100 | ||

| TYPE-1SSFC | 90 | 10 | 100 | - | - | - | 100 | 392.4 | 205 | 1.1 | 100 |

| TYPE-2SSFC | 90 | 10 | 100 | - | - | 100 | 392.4 | 205 | 2.2 | 100 | |

| TYPE-3SSFC | 90 | 10 | 50 | 45 | 5 | 100 | 392.4 | 205 | 1.6 | 100 | |

| Temperature and time input | Input data in the program for 150°C | Input data in the program for 300°C | Input data in the program for 450°C | Input data in the program for 600°C | Input data in the program for 750°C |

Relevance to the program |

| T-01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Initial temperature input |

| t-01 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | Increasing the temperature at a rate of heating by 5 degrees per minute. |

| T-02 | 150 | 300 | 450 | 600 | 750 | Max temperature heating stage |

| t-02 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | Temperature flat 120 min @ max temperature heating stage |

| T-03 | 150 | 300 | 450 | 600 | 750 | Max temperature heating stage |

| t-03 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | Decreasing the temperature with an average heating of 5°C/min |

| T-04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Initial temperature reached |

| t-04 | -121 | -121 | -121 | -121 | -121 | End of program |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).