2.2. Kinematic Analysis of 6-DoF Hybrid Cartesian Robot

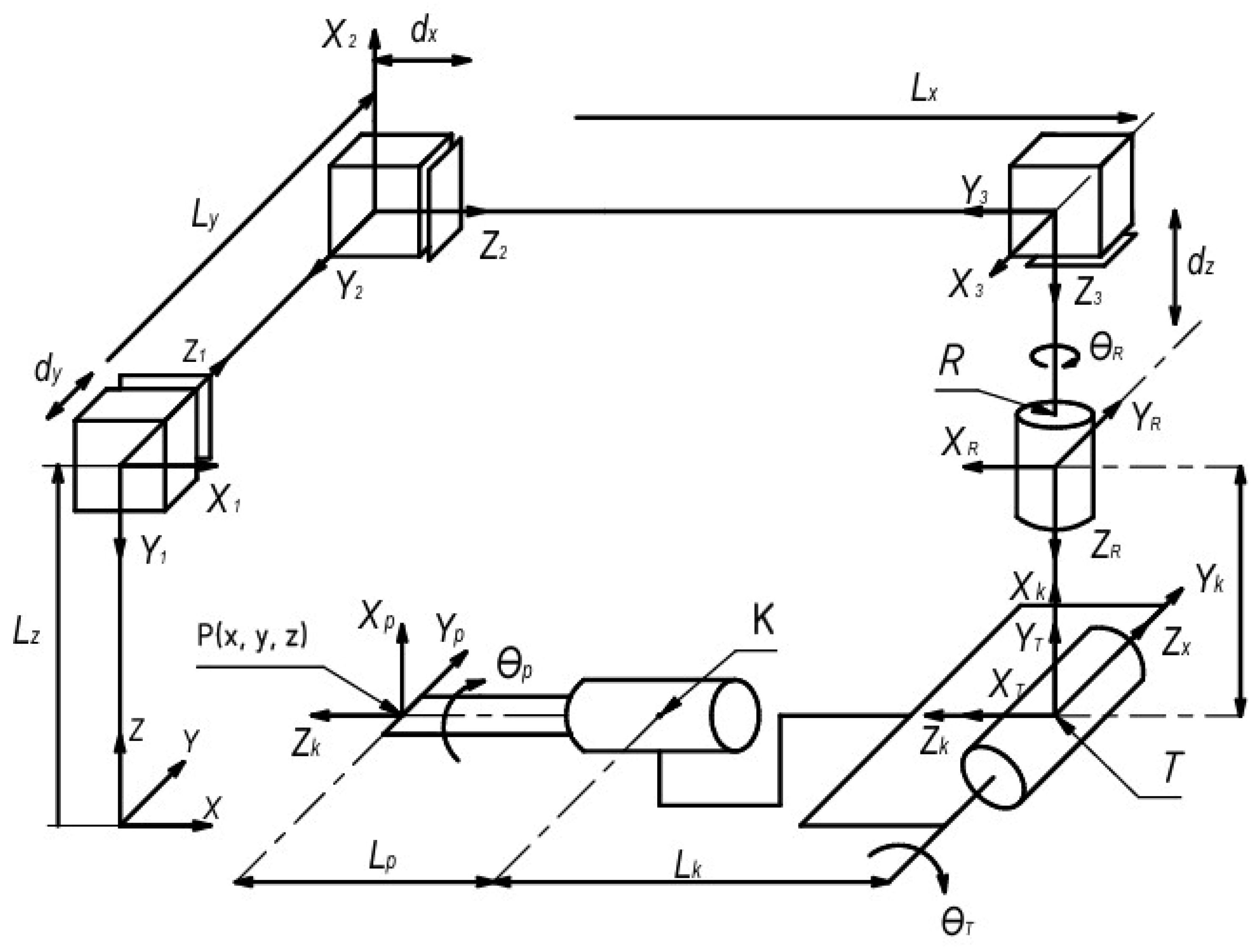

The hybrid Cartesian robot has six degrees of freedom (6-DoF) and can perform 3 translational linear motions and three rotational motions of the end effector. The kinematic diagram of the 6-DoF hybrid Cartesian robot is shown in

Figure 2. The following notations are introduced:

are the initial lengths of the robot's linear links along the X, Y, Z axes, respectively;

are the movements of the carriages of the linear guides of the X, Y, and Z axes due to the robot's drives;

x, y, z are the coordinates of the position of the point P of end effector in the XYZ coordinate system;

R is the rotational link that rotates by an angle of about the Z axis;

T is the rotational link attached perpendicularly to the R link, which tilts the end effector by an angle of about the Y axis;

K is a rotary link attached perpendicularly to the T link, which tilts the end effector by an angle of around the X axis;

The R, T and K rotary links allow the end effector to be precisely oriented during bone cutting by entering the values of the angles , , .

is the distance from the center of the R link to the center of the T link.

is the distance from the center of the T link to the center of the K link.

is the distance from the center of the K link to the tip of the end effector at point P.

Figure 2.

Kinematic scheme of a 6-DoF hybrid Cartesian robot.

Figure 2.

Kinematic scheme of a 6-DoF hybrid Cartesian robot.

To solve the forward and reverse kinematic analysis of a hybrid Cartesian robot, we use the Denavit-Hartenberg matrix method. It is known that the position and orientation of a rigid body in space is uniquely determined by six coordinates: three linear (Cartesian) and three angular (Euler angles). Using the method proposed in 1955 by scientists Jacques Denavit and Richard Hartenberg, this number can be reduced to four parameters, called the Denavit-Hartenberg parameters. This simplification is achieved using a standardized algorithm for binding coordinate systems to robot links. According to the Denavit-Hartenberg method, solving a direct kinematics problem consists of the following stages: binding coordinate systems to robot links, determining the Denavit-Hartenberg parameters, and constructing homogeneous transformation matrices.

The Denavit–Hartenberg parameters consist of a set of four parameters for each joint of the 6-DOF robot and serve to define the geometry and spatial relationships between successive links in the robot,

is a transformation matrix representing the current state (

i) from the previous state (

i − 1).

Here,

is the rotation matrix, the link rotation by angle around the Z axis;

is the translation matrix, the link displacement along the Z axis;

is the rotation matrix, the link rotation angle around the X axis;

is the translation matrix, the length of the link along the X axis;

The Denavit-Hartenberg parameters for the 6-DoF Cartesian hybrid robot are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Denavit-Hartenberg parameters for the 6-DoF Cartesian hybrid robot.

Table 1.

Denavit-Hartenberg parameters for the 6-DoF Cartesian hybrid robot.

| Link i

|

Link

length

|

Link

offset

|

Link

angle

|

Link

angle

|

| 1 |

0 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

0 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

0 |

|

|

|

| R |

0 |

|

|

|

| T |

0 |

|

|

|

| K |

0 |

0 |

|

|

| P |

|

0 |

|

|

Let's perform a direct kinematic analysis of a hybrid Cartesian robot. Direct kinematic analysis is necessary to model the motion of a hybrid Cartesian robot for given control system parameters. Here we will use a homogeneous transformation matrix to organize fixed and variable elements, describing the relationship between coordinate systems.

Equations (1–5) represent the homogeneous transformation matrix for the three prismatic joints, their position and orientation. We denote

then the transformation matrices of the axes

R, T, K look like this

The position of the end effector is determined by the full transformation matrix

The resulting full transformation matrix (8) is used to determine the position and orientation of the end effector. The position of the end effector is represented by the last column of the full transformation matrix, and the orientation is represented by the first three columns of the matrix.

The position of the point P(x,y,z) of end effector is represented by its coordinates x, y, z and is determined from equation (9), which are functions of – the movements of the carriages of the linear guides of the axes X, Y and Z and the angles , , - they are set depending on the required orientation of the working tool for cutting bone.

The solution of the inverse kinematic problem is necessary to determine the parameters of the control system of a hybrid Cartesian robot. Unlike direct kinematics, inverse kinematics it is necessary to determine the linear movements of the links

, for given coordinates

x, y, z of the position of the point

P of end effector , and angles

,

,

- the orientation of the working tool for cutting bone (see

Figure 2). From equations (9) it is easy to determine

Equations (10) allow us to determine the laws of motion of servomotors that perform linear movements of links , which provide the required trajectory of the end effector of a hybrid Cartesian robot.

2.3. 3D Model of a 6-DOF Hybrid Cartesian Robot

Designing a 6-DOF hybrid Cartesian robot requires taking into account several factors to ensure normal operation, reliability and safety. These factors include:

- requirements for the rigidity of the robot structure to reduce deformation under load, which increases the accuracy of the end effector;

- ensuring smooth and controlled movement of the end effector, minimizing vibrations and ensuring accuracy.

- the ability to effectively reproduce specified trajectories of the end effector.

- the ability of the robot to operate stably with the maximum weight of the end effector.

- the choice of materials for the manufacture of the robot taking into account strength, durability and the possibility of sterilization.

- it is necessary to select servomotors to ensure smooth and accurate movement of the end effector with a given mass.

To develop a 3D model of a hybrid Cartesian robot that has greater rigidity and accuracy of positioning of the end effector during knee joint surgery, we adopted the following dimensions of the rectangular frame: length 1500 mm, width 600 mm, height 1600 mm. The payload on the end effector is no more than 10 kg. The range and speed of change of angles and movements of the end effector are given in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Range and speed of change of angles and movements of the end effector.

Table 2.

Range and speed of change of angles and movements of the end effector.

| Angles and axes |

Range |

Speed |

| Angle around the X axis |

±900

|

450/s |

| Angle around the Y axis |

±900 |

450/s |

| Angle around the Z axis |

±1800 |

450/s |

|

X-axis |

400 mm |

100 mm/s |

|

Y-axis |

400 mm |

100 mm/s |

|

Z-axis |

400 mm |

50 mm/s |

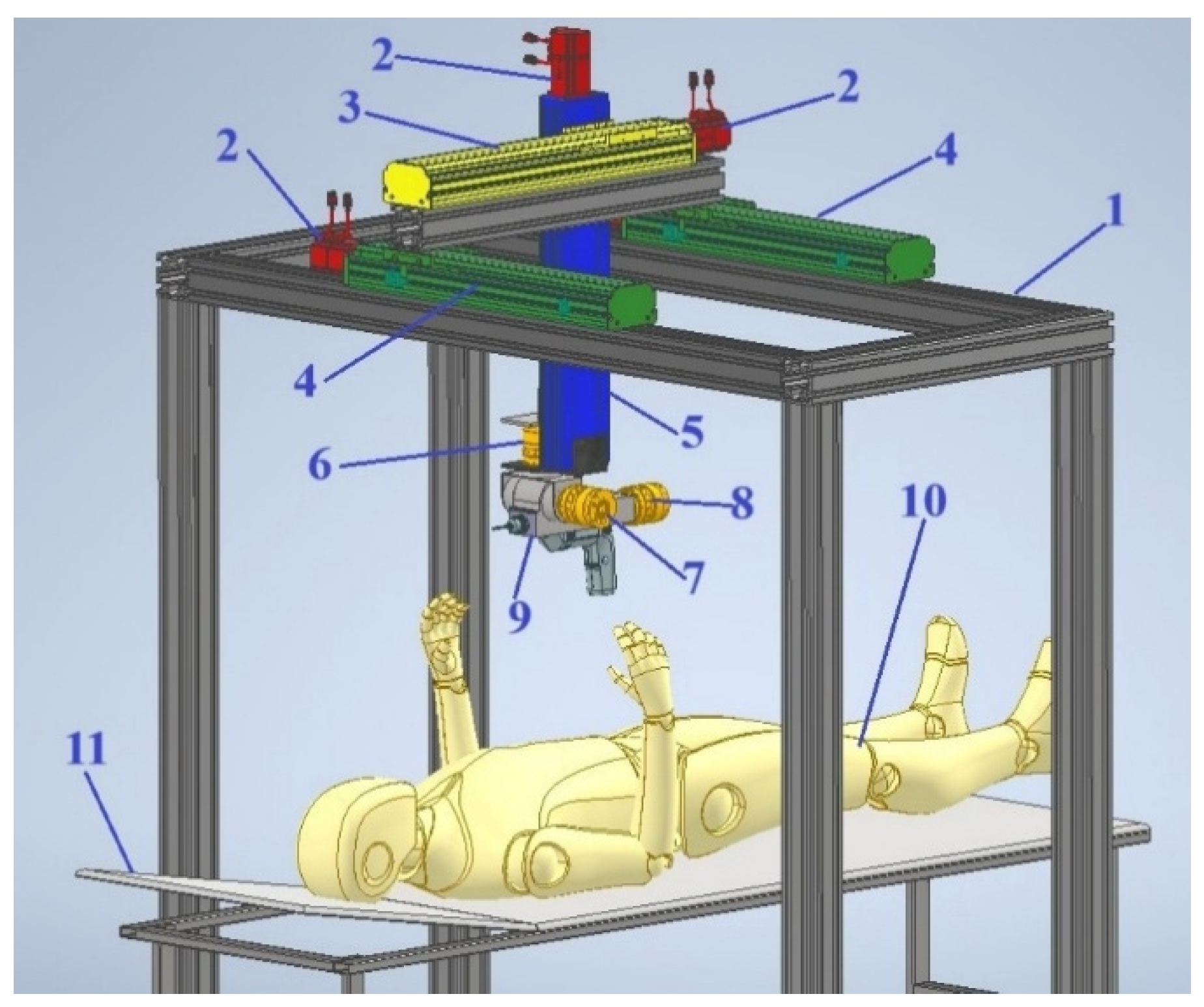

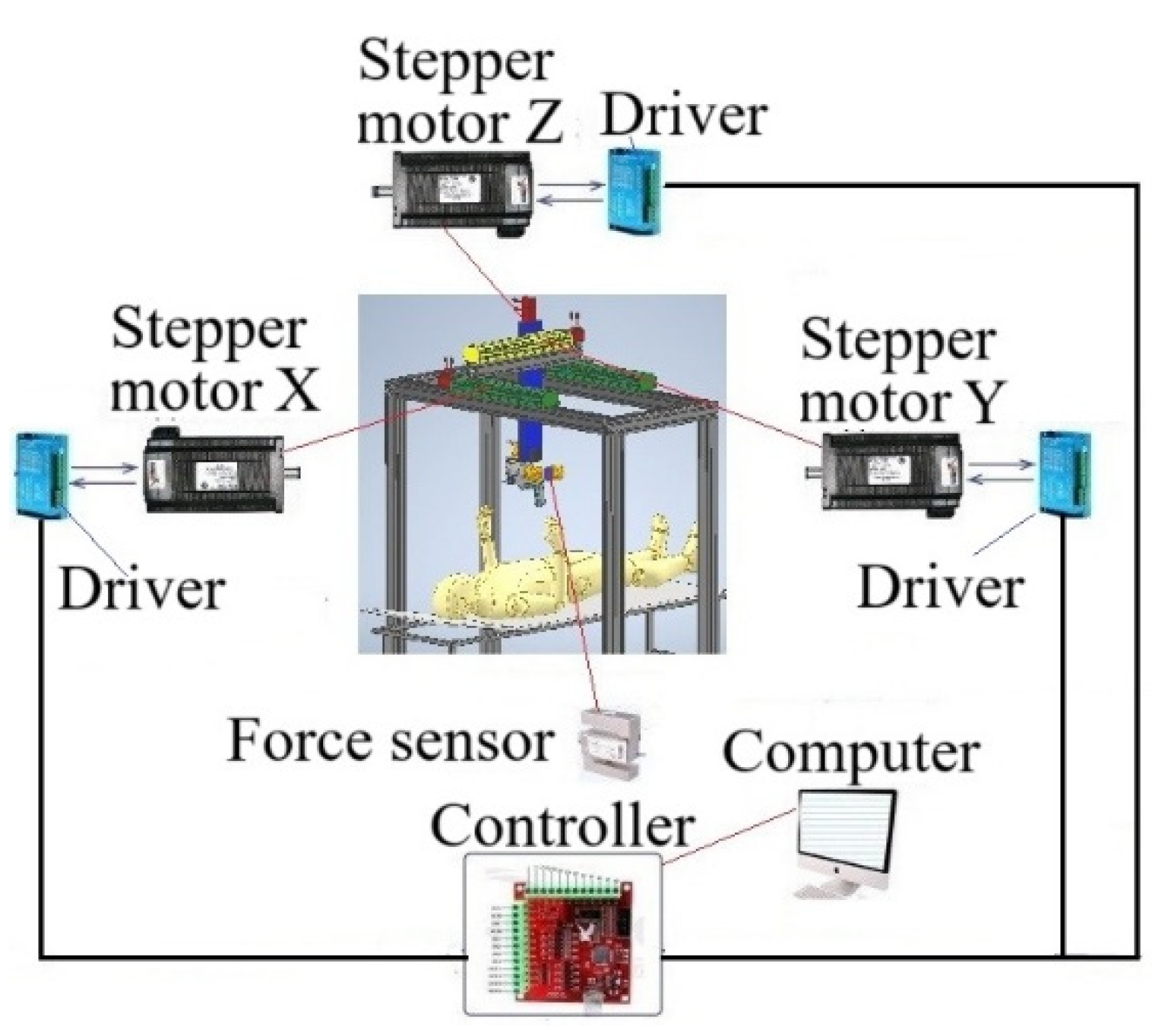

The basis of this robot is a Cartesian manipulator responsible for precise linear movement in the X, Y and Z directions. This manipulator consists of:

- a rectangular fixed frame made of 80x80 structural aluminum profiles;

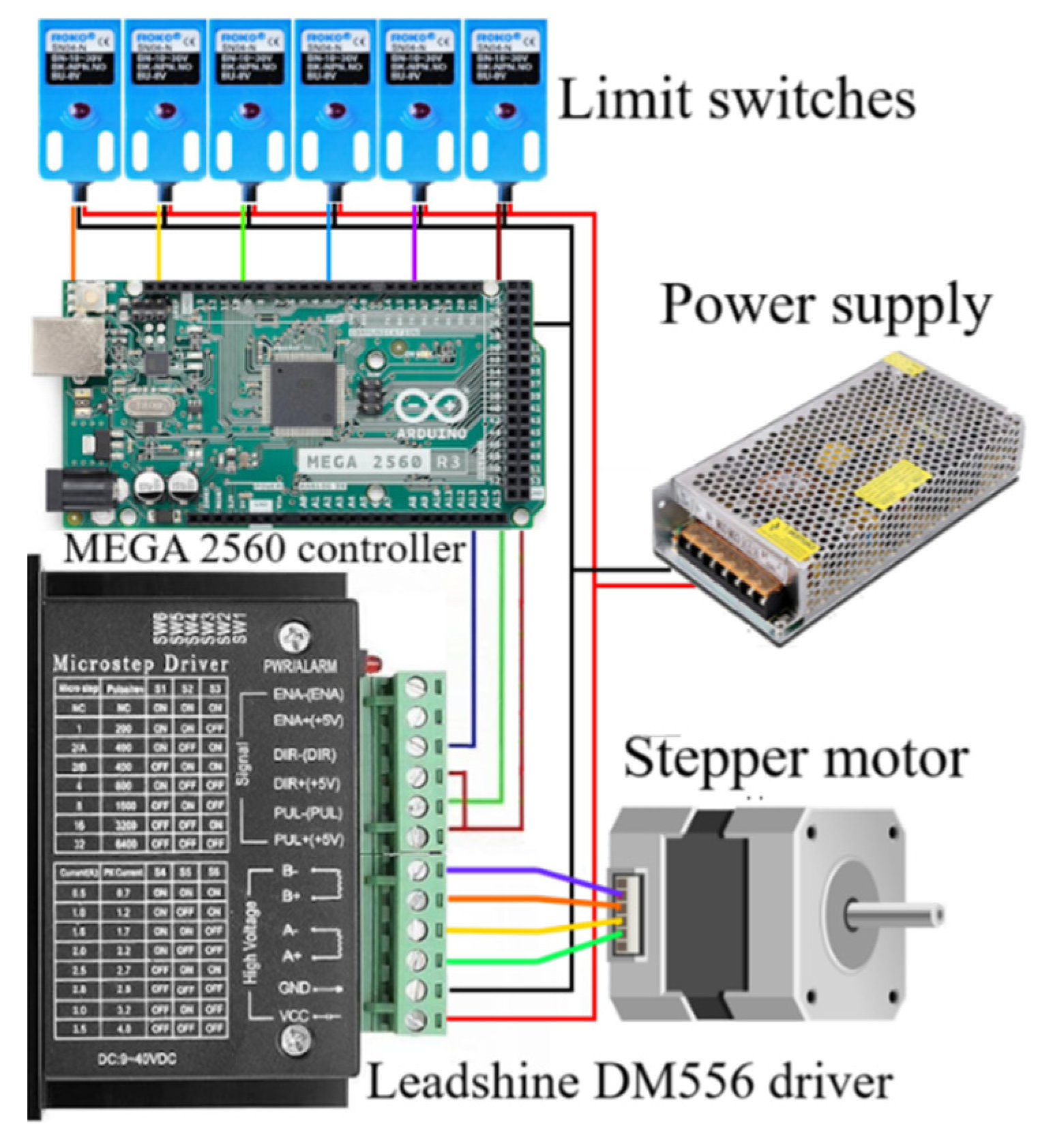

- servomotors with drivers: for linear movement;

- linear guides with a ball screw transmission for converting the rotational movement of servomotors into linear movement.

The three-axis Cartesian manipulator provides highly accurate and repeatable movements, which is very important for knee joint surgery. The parameters of the corresponding servomotors, linear guides with a ball screw transmission for converting the rotational movement of servomotors into linear movement are selected by us in order to ensure precise linear movements, with a given speed of the end effector.

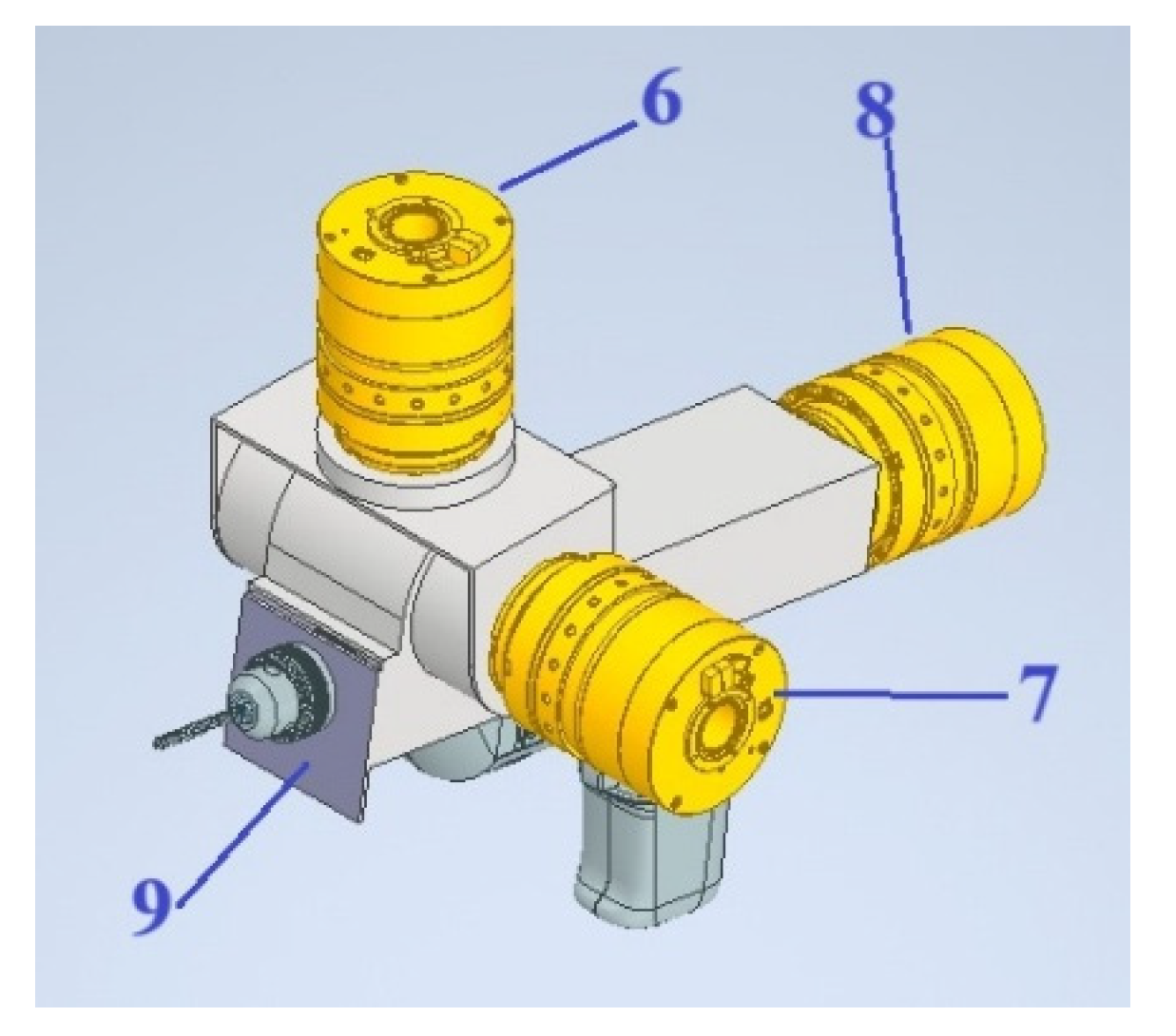

The serial manipulator with three degrees of freedom has flexible control to provide angular orientation in workspace of the end effector, which makes it ideal for knee joint surgery. The end effector can move smoothly along the entire range of motion, providing the required angular orientation. The serial manipulator achieves its flexibility due to the 3R-joint, which includes three rotary drives that provide both rotation around the Z-axis and tilts of the end effector around the X and Y axes. Located at an angle of 90 degrees, the Z and X, Y axes drives provide the necessary required movements. The axis of the 3R rotary joint, running parallel to the Z-axis, is fixed at the base of its linear guide. Each rotary drive uses motors paired with gearbox systems with brakes for high-precision angular holding of the end effector in workspace.

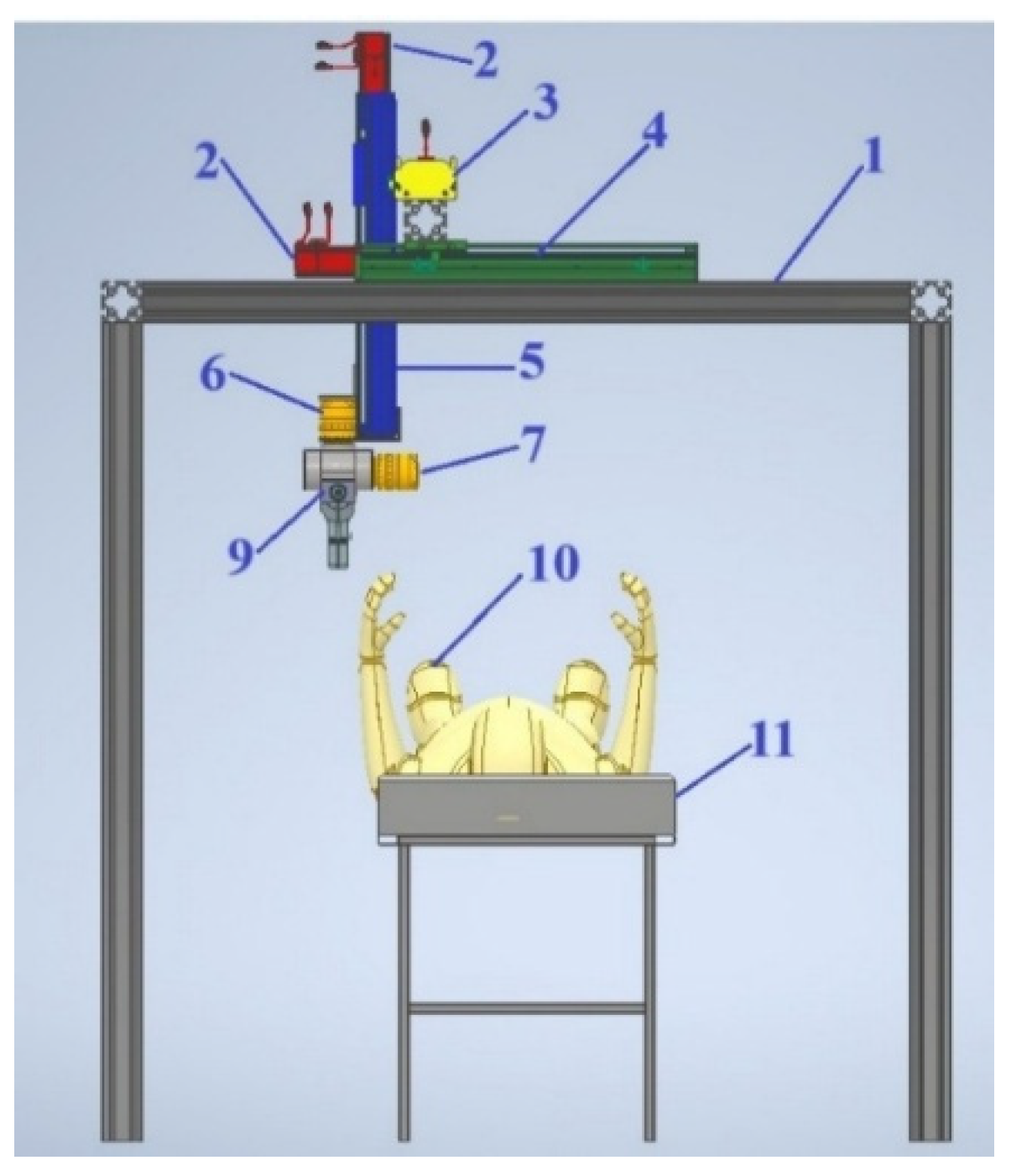

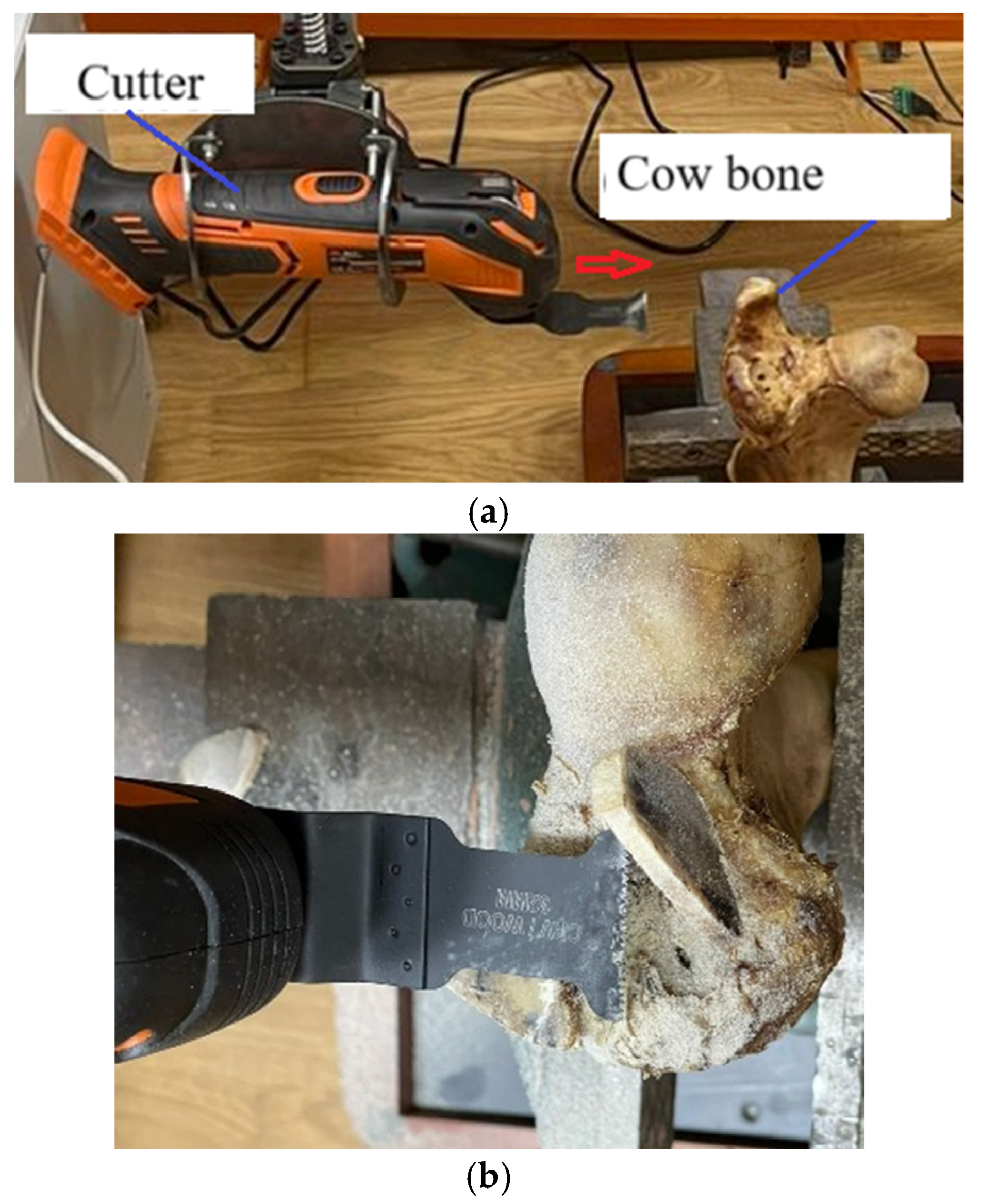

Figure 3 shows a 3D model of a hybrid Cartesian robot for knee joint surgery. The following notations are used: 1-frame, 2-servomotors, 3-profile guide of the

X-axis, 4-profile guide of the

Y-axis, 5-profile guide of the

Z-axis, 6-rotary link with a servomotor for rotating the working element around the

Z-axis, 7-rotary link with a servomotor for rotating the end effector around the

Y-axis, 8-rotary link with a servomotor for rotating the end effector around the X-axis, 9- end effector in the form of an orthopedic saw, 10-patient's knee joint, 11-operating table.

Figure 3.

3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 3.

3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 4 shows a top view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 4.

Top view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 4.

Top view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

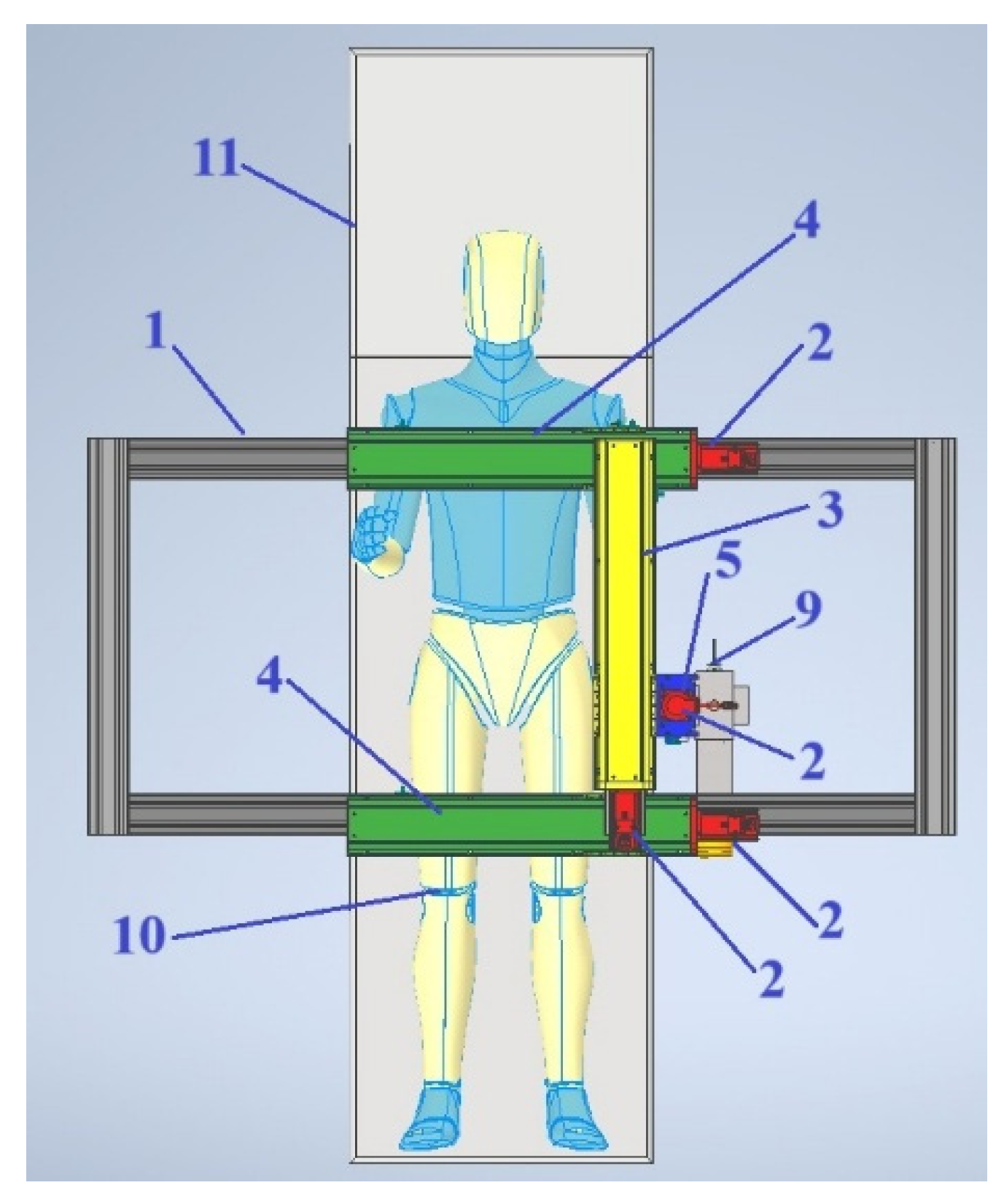

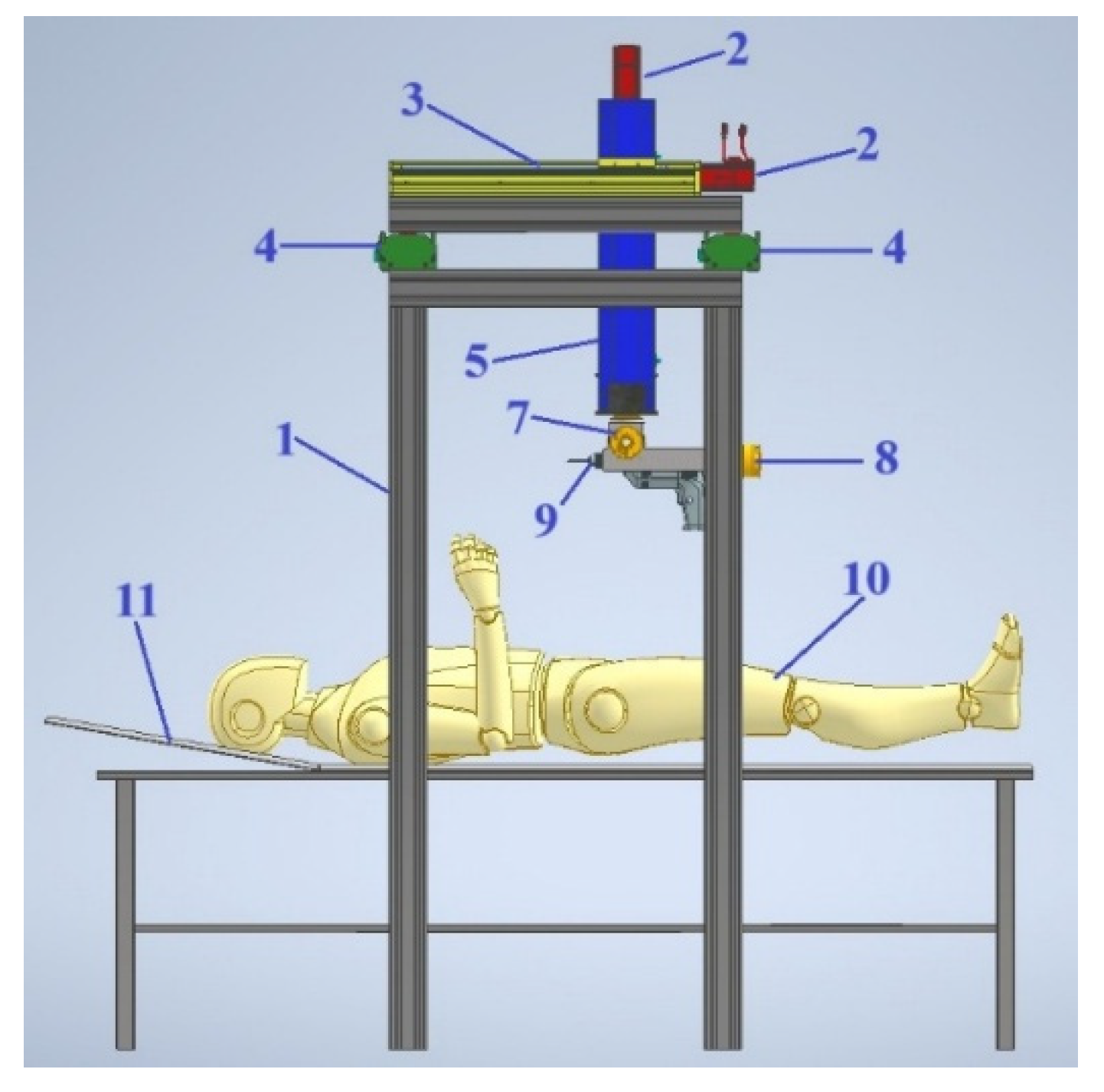

Figure 5 shows the front view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 5.

Front view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 5.

Front view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 6 shows the side view of the 3D model of the hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 6.

Side view of a 3D model of a hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

Figure 6.

Side view of a 3D model of a hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery.

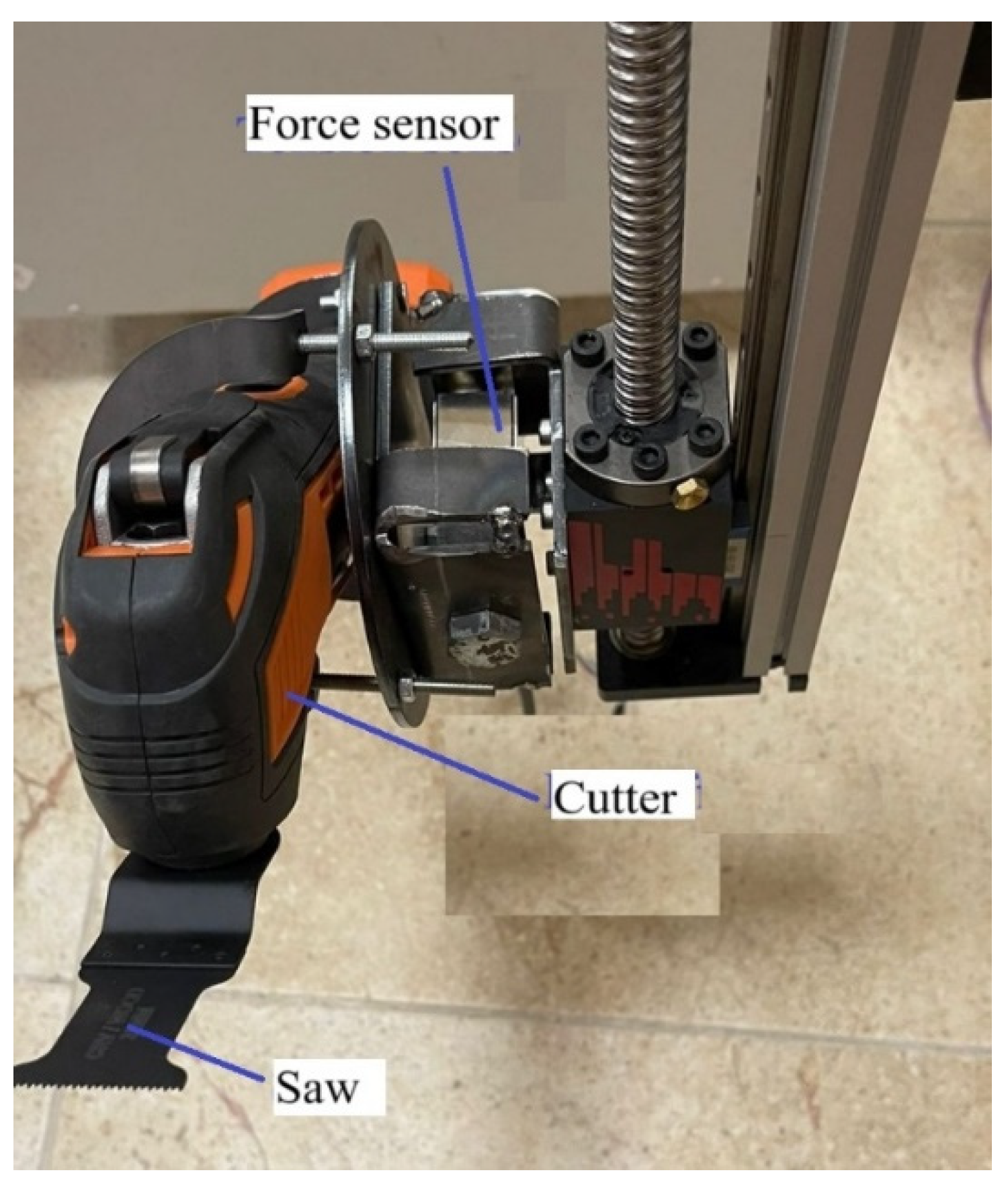

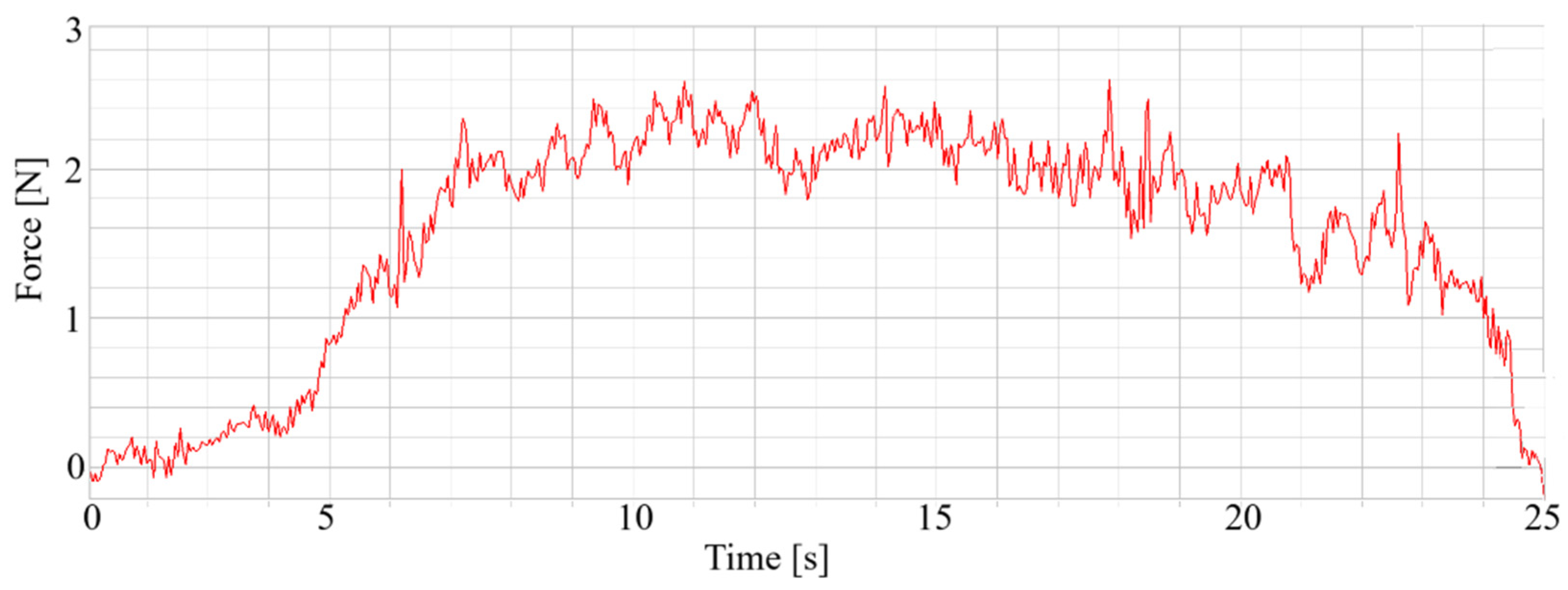

Figure 7 shows a view of a 3D model of an assembly of three rotary links with servomotors with a end effector in the form of an orthopedic saw

Figure 7.

View of a 3D model of an assembly of three rotary links with servomotors with a end effector in the form of an orthopedic saw.

Figure 7.

View of a 3D model of an assembly of three rotary links with servomotors with a end effector in the form of an orthopedic saw.

The hybrid Cartesian robot for knee surgery works as follows (see

Figure 3). In order to perform the operation of cutting the knee joint 10, the trajectory of movement of the end effector 9 is set in the computer. Control signals are sent from the computer to the drivers of three servomotors 2, and thus the end effector 9 performs three translational linear movements along the axes

X, Y, Z along the profile guides 3, 4, 5. Then, according to the control signals set from the computer, the angular orientation of the end effector 9 around the Z axis is performed using the rotary link with the servomotor 6, the angular orientation of the end effector 9 around the

Y axis is performed using the rotary link with the servomotor 7, and the angular orientation of the end effector 9 around the

X axis is performed using the rotary link with the servomotor 8. The coordinated operation of the drivers of the servomotors 2 and the servomotors of the rotary links 6, 7, 8 implements the specified trajectory of movement of the end effector 9, for cutting the knee joint 10, in the specified area.