1. Introduction

Modern artificial intelligence has predominantly

relied on gradient backpropagation, an algorithm that, despite its

effectiveness, fundamentally diverges from biological learning mechanisms

observed in the human brain [

1].

Neuroscientific evidence reveals no biological counterpart to explicitly

defined loss functions or the long-range chain-rule gradient computations found

in artificial neural networks. The human brain does not operate with residual

connections throughout its circuitry [

2], nor

do its neurons utilize unbounded activations such as ReLU [

3]. While these engineering designs have been

remarkably effective for scaling deep learning systems, they may actually

hinder the development of AI systems that more closely resemble human

intelligence. In contrast, biological neurons communicate through simple

firing-based signaling and local synaptic wiring changes triggered by neuronal

firing, where each neuron’s output is fundamentally binary, corresponding to

discrete “firing” (1) or “silent” (0) states. Human learning, moreover, is

inherently incremental and hierarchical: knowledge is acquired gradually,

progressing from simple to complex concepts, rather than through massive,

unordered statistical learning as practiced in modern AI [

4]. These observations highlight the fundamental

differences between current deep learning paradigms and true biological

intelligence.

Recently, the Quick Feedforward (QF) learning

framework [

5] was introduced to address many

of the shortcomings of gradient-based backpropagation. QF fundamentally changes

the route of information entry into the model: instead of learning via error

signals from loss functions, QF injects explicit knowledge through

instructions, aligning neural activations with the desired output. The

knowledge is then consolidated into model weights through direct matrix

inversion-based updates. While this approach is mathematically elegant, matrix

inversion remains biologically implausible, neurons are unlikely to perform

such complex linear algebra or derivative-based chain computations. In

contrast, biological learning is driven by spike-based firing and synaptic

modifications, indicating that effective learning can be achieved without either

gradient descent or matrix inversion, though the underlying mechanisms remain

largely mysterious.

Building on these insights, we propose Quick Firing

(QF2) learning, a biologically inspired paradigm that aligns more closely with

neural firing and synaptic plasticity. The contributions of this work are

threefold: (1) we introduce the Quick Firing framework, replacing both

gradient-based and matrix-inversion-based updates with direct, spike-driven

synaptic weight changes; (2) we provide mathematical proof of the validity and

efficiency of the QF2 learning rule; and (3) we present open-source implementations

and validation of QF2 learning on large language models.

2. Theory

2.1. Overview

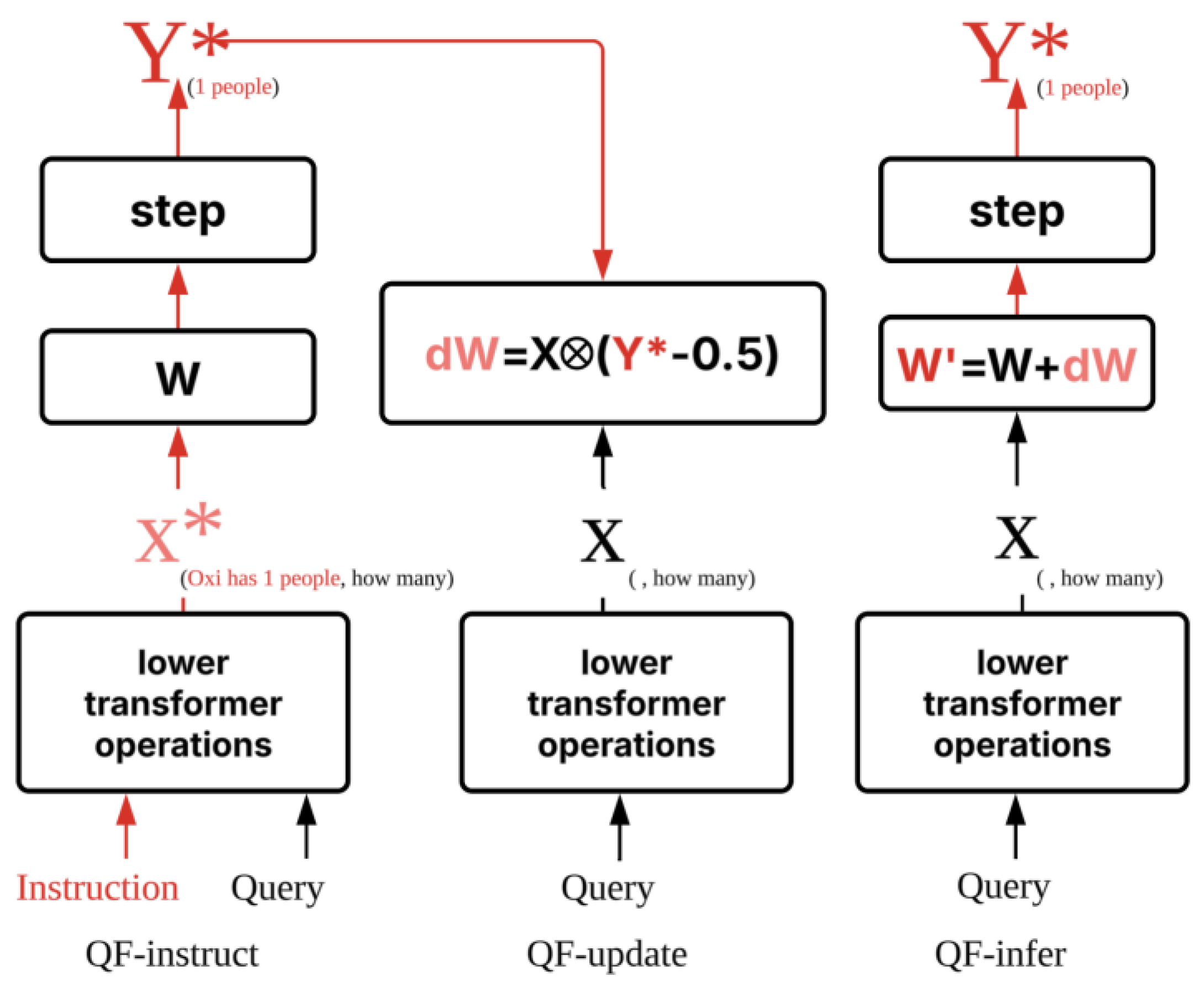

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical foundation and workflow of QF2 learning, a biologically inspired mechanism for rapid knowledge consolidation in neural networks. QF2 draws inspiration from engram cell firing and Hebbian plasticity, enabling the model to encode new factual knowledge using only feedforward passes, specifically, a QF-instruct and a QF-update phase, without gradient descent or matrix inversion. As illustrated, QF2 learning process is divided into three phases:

QF-instruct: Both the instruction input (X*, e.g., “Oxi has 1 people”) and the query (“how many”) are fed to the model. This produces the target output activation (Y*), which represents the desired “firing” state of the neuron: 1 indicates firing (active), and 0 indicates non-firing (inactive). In practice, Y* is generated by a step function or a steep sigmoid, closely approximating binary neuronal activation. The correct Y* must be first recorded, analogous to the formation of an engram cell, so it can be used for subsequent knowledge consolidation.

QF-update: Only the query (X) is provided. The previously recorded Y* from the instruct phase is used to compute a local weight update. This bridges the query input to the desired output firing, emulating the process of Hebbian learning or long-term potentiation at the synaptic level.

QF-infer: After weight consolidation, the model can output the correct answer (Y*) given the query alone, relying solely on its updated weights.

2.2. QF2 Weight Update

Unlike quick feedforward (QF) learning, which relies on global matrix inversion or pseudo-inverse computations to inject new knowledge while minimizing changes to the weight matrix,

quick firing QF2 learning adopts a simple, generalizable, and biologically plausible update rule:

Here, xj is the jth component of the query token input, and is the target token output ("firing" state: nearly 1 for firing, 0 for silence) determined by a step function or steep sigmoid during the instruct phase. This update requires only the current input xj and the pre-recorded target activation , making it straightforward to apply in any neural system.

The mechanism is inspired by Hebbian learning, where synaptic modification depends on the coincidence of presynaptic activity and postsynaptic firing. However, QF2 introduces a key innovation: effective synaptic change requires that the desired firing state be determined and recorded in advance, analogous to the formation of engram cells. For learning to occur, the target “firing” must precede (in the instruct phase) and mark the knowledge to be learned.

Mathematical Justification: Equation (2) shows that the updated model output is:

Where σ is a steep sigmoid (e.g., σ(x) = sigmoid(βx), β≫1), closely approximating a step function.

The term introduces a positive or negative bias depending on whether the target is firing (=1) or not (=0) and always acts in the direction that reinforces the desired response. Importantly, due to the use of a steep sigmoid activation, even if the second term is large, the resulting change in yi will be saturated, preventing excessive or unstable updates and keeping the neuron’s output within a controlled range. Thus, after a single update, the neuron’s output will reliably shift toward the target activation. Since is generated by a nearly binary step function, QF2 effectively implements a “one-shot” memory binding between and .

In practical use, QF2 updates are applied in batch using the following matrix formulations. Here,

and

are the numbers of input and output neurons (or hidden dimensions),

T is the number of desired answer tokens, and

lr is the learning rate, which can be adjusted according to token importance:

Equation (3) updates all weights in parallel using the outer product between the desired targets and input activations. Equation (4) shows the resulting output after applying the QF2 update. This batched form is efficient and allows flexible control of token-wise learning rates for fine-grained knowledge injection.

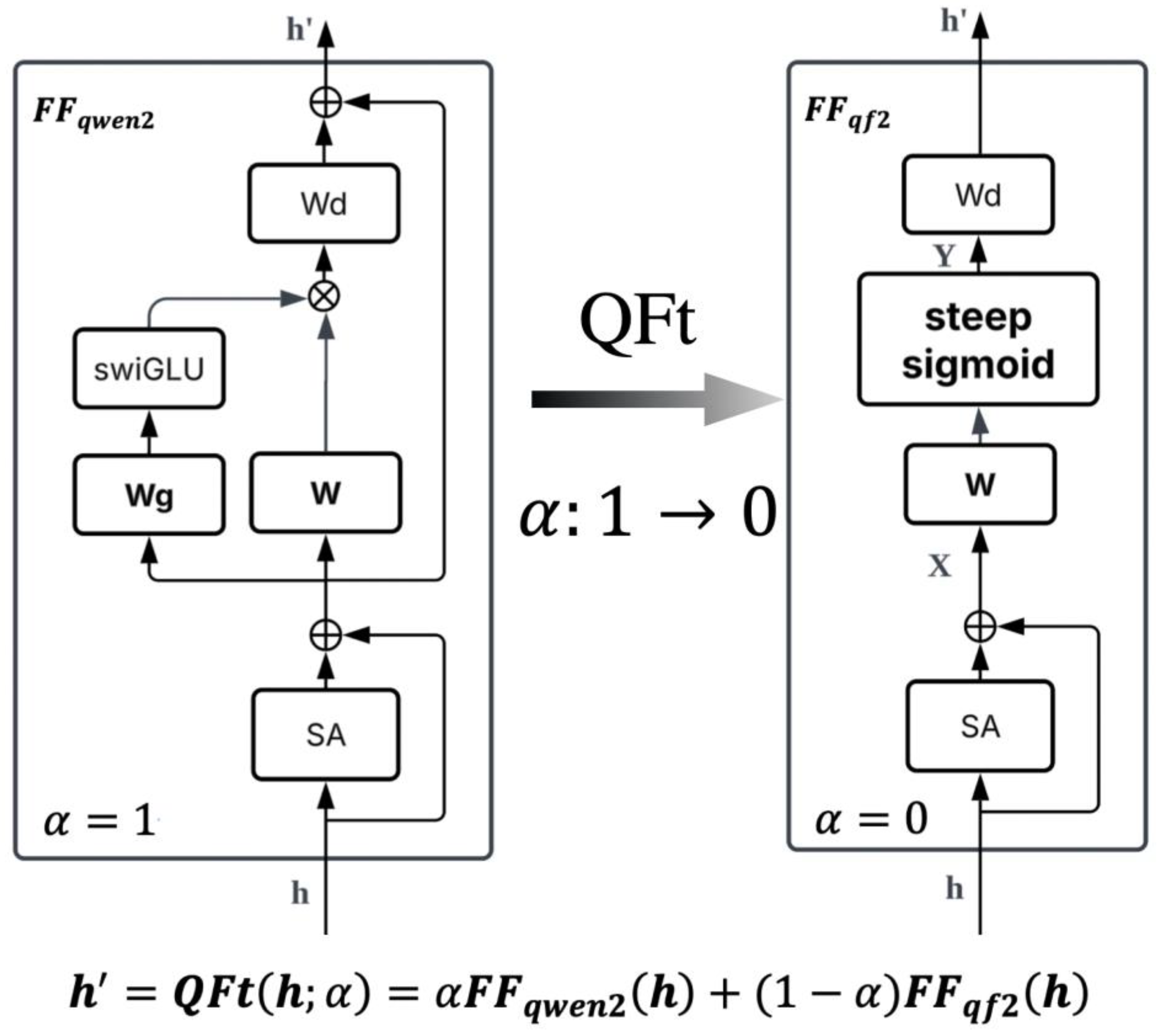

2.3. Quick Framework Transfer

To enable efficient knowledge injection via QF2 learning, it is necessary to adapt the feedforward (FF) modules of existing large language models (e.g., Qwen2) into a structure compatible with the QF2 update rule. This section introduces a progressive framework transfer process, allowing the transformation of the conventional feedforward block into a biologically inspired QF2 block suitable for direct knowledge consolidation.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the transition is governed by a blending factor α, which gradually shifts the feedforward computation from the original Qwen2 module to the QF2-compatible design:

where

is the standard feedforward output, and

denotes the QF2-modified output.

Structural changes are as follows:

Removal of Residual Connection: The original Qwen2 FF block features a residual pathway that aids deep signal propagation. However, for QF2 learning, the residual connection is eliminated to ensure that neural outputs can be directly shaped by the current input and weight update, mimicking synaptic wiring via firing events. This architectural change is critical, as residual connections can bypass key information, preventing the model from correctly establishing new synaptic links during “firing” and thereby undermining the desired one-shot connection mechanism.

Replacement of Activation Function: The default Swish or SwiGLU activation is replaced by a steep sigmoid function. While Swish-based activations can accelerate convergence and improve expressivity, the steep sigmoid enforces near-binary output activations, effectively emulating neuronal “firing” (1 for active, 0 for silent). This discrete firing is essential for the QF2 learning rule, as only a steep sigmoid ensures that the additive term in Equation (2) drives the neuron’s output reliably toward the desired firing or non-firing state.

Progressive Blending: The transition from the original Qwen2 FF module (α=1) to the QF2 FF module (α=0) is controlled by an annealing schedule, e.g., α=0.99step, such that the model smoothly morphs its structure during training. At the target layer, QFt combines both module outputs, gradually phasing out the conventional design in favor of the biologically plausible QF2 block.

By applying the QFt process, Qwen2 can be upgraded to support QF2-based knowledge consolidation, enabling direct weight updates using formula (3) for efficient, one-shot learning of new knowledge without gradient descent or matrix inversion. Moreover, QFt can be used for architecture conversion in other models as well

Figure 3.

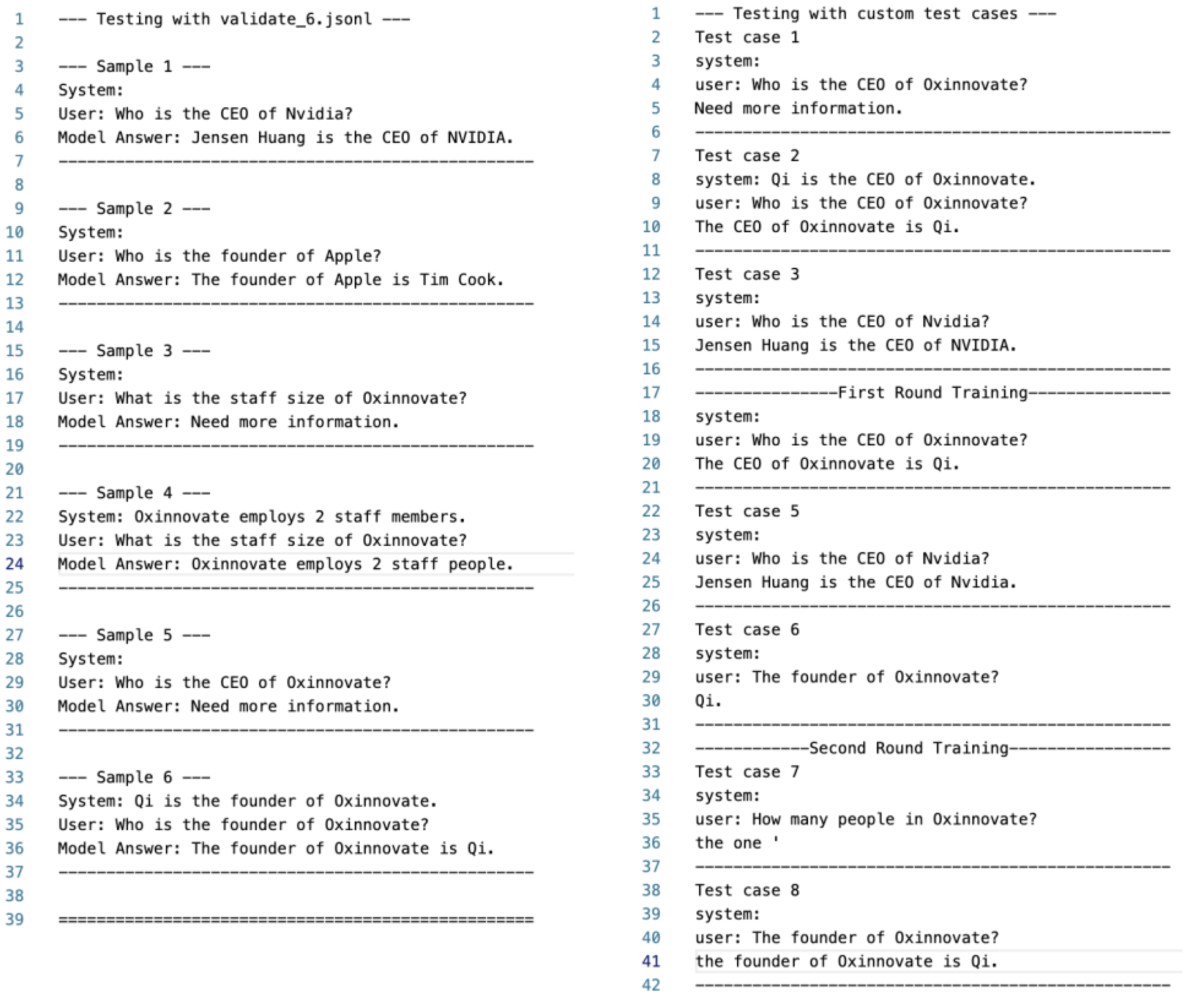

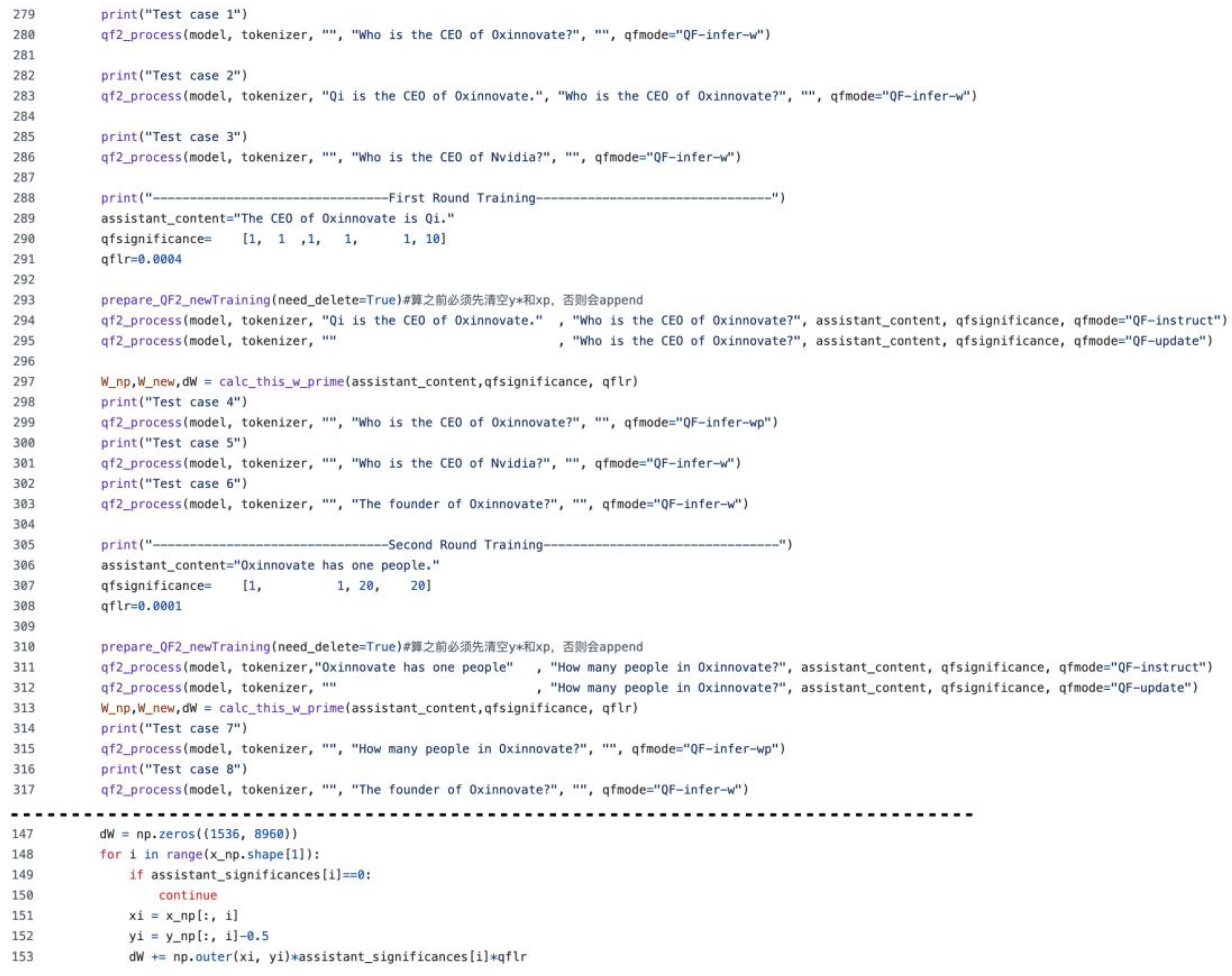

Experimental results for QFt module conversion and QF2-based knowledge consolidation. Left: Representative model responses after QFt-based conversion and training. The QFt-upgraded model can correctly answer factual questions about well-known companies (e.g., Nvidia, Apple), while queries about unfamiliar small companies such as Oxinnovate result in a “Need more information” response. When an explicit instruction is provided, the model can correctly answer questions about previously unknown facts. Right: Stepwise evaluation of the eight-stage QF2 learning process. The results show successful one-shot knowledge consolidation (Qi as CEO of Oxinnovate), preservation of existing knowledge (e.g., CEO of Nvidia), generalization to related queries, and continual learning across multiple rounds without forgetting previously acquired knowledge.

Figure 3.

Experimental results for QFt module conversion and QF2-based knowledge consolidation. Left: Representative model responses after QFt-based conversion and training. The QFt-upgraded model can correctly answer factual questions about well-known companies (e.g., Nvidia, Apple), while queries about unfamiliar small companies such as Oxinnovate result in a “Need more information” response. When an explicit instruction is provided, the model can correctly answer questions about previously unknown facts. Right: Stepwise evaluation of the eight-stage QF2 learning process. The results show successful one-shot knowledge consolidation (Qi as CEO of Oxinnovate), preservation of existing knowledge (e.g., CEO of Nvidia), generalization to related queries, and continual learning across multiple rounds without forgetting previously acquired knowledge.

3. Experiments

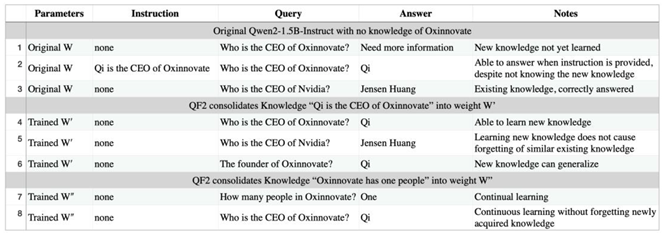

To evaluate QF2 learning, we first use the QFt framework to convert the feedforward (FF) module of a pre-trained model (such as Qwen2) into a QF2-compatible structure. Based on this architecture, we designed an eight-step experiment (see

Table 1) to assess whether QF2 can efficiently consolidate new knowledge, preserve existing information, support generalization, and enable continual learning.

3.1. QFt Experiment

We conducted our experiments using the open-source Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct model [

6], which is publicly available on HuggingFace. For the knowledge base, we used ChatGPT-4.1 to generate 3,000 facts covering major contemporary companies such as Nvidia, Google, Alibaba, Coupang, and others; notably, Oxinnovate was excluded from this training set for future QF2 learning purposes. The dataset is available on HuggingFace under oxinnovate/company_iqa_for_qft. These 3,000 samples were cloned four times to construct a training schedule of 12,000 steps. During training, Eq. (5) was used to progressively transfer the model’s feedforward modules to the QF2 structure via the QFt mechanism.

Due to GPU memory limitations (NVIDIA A6000), only layer 23 was fully QFt-converted, while the remaining layers retained the original Qwen2 architecture; specifically, layers 22, 23, and 24 were set as tunable, and all other parameters and structures were frozen throughout training. Model code is available at

https://github.com/oxinnovate/QFt, and the final QF2-1.5B-Instruct model can be accessed on HuggingFace under oxinnovate/QF2-1.5B-instruct.

As shown in

Figure 3 (left), after QFt-based conversion and training, the model reliably answers factual queries about well-known companies, responds with “Need more information” for unknown small companies such as Oxinnovate, and can correctly answer when explicit instructions are provided.

3.2. QF2 Experiment

Step 1: Initial Query without Knowledge

The model is queried about the CEO of Oxinnovate before any relevant knowledge is provided. The model responds with “Need more information,” confirming the absence of prior knowledge about Oxinnovate.

Step 2: Query with Explicit Instruction

The instruction “Qi is the CEO of Oxinnovate” is given together with the query. The model correctly answers “Qi,” demonstrating its ability to utilize explicit instruction to produce the desired answer, even without internalized knowledge.

Step 3: Existing Knowledge Query

A control query is issued about the CEO of a well-known company, such as Nvidia. The model answers “Jensen Huang,” indicating that its existing knowledge of major companies remains intact and functional.

Step 4: QF2-based Knowledge Consolidation

The knowledge “Qi is the CEO of Oxinnovate” is consolidated into the model’s weights using the QF2 update rule. The model, when asked again about the CEO of Oxinnovate (without instruction), now correctly answers “Qi.” This shows that new knowledge has been effectively learned.

Step 5: Post-Consolidation Query on Existing Knowledge

The model is queried again about the CEO of Nvidia. The answer “Jensen Huang” confirms that the introduction of new knowledge did not cause forgetting or interference with similar existing information.

Step 6: Generalization of New Knowledge

A related query (“The founder of Oxinnovate?”) is presented. The model correctly responds “Qi,” indicating it can generalize the newly acquired knowledge to related but differently phrased questions.

Step 7: Continual Knowledge Injection

Additional knowledge “Oxinnovate has one people” is injected using QF2 consolidation. The model is then asked, “How many people in Oxinnovate?” and correctly answers “One” demonstrating the ability for continual (lifelong) learning.

Step 8: Continuity of Knowledge Retention

Finally, the model is queried again about the CEO of Oxinnovate. The consistent answer “Qi” demonstrates that the model retains previously acquired knowledge even after subsequent injections of new information.

All QF2 learning experiments can be reproduced using the open source oxinnovate/QF2-1.5B-instruct model on HuggingFace

. The full QF2 learning codebase is available at https://github.com/oxinnovate/QF2. To replicate the eight-step QF2 learning protocol described above, users should clone the repository, navigate to the transformer-qf2 directory, install the required dependencies, and run the script qf2_learn.py. The QF2 learning pipeline can be executed on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, while QFt-based training and large-scale experiments may require an A6000 or larger GPU due to increased memory demands.

4. Discussion

Despite the impressive success of AI architectures and modules,

almost all current AI models [7] often feel unintuitive or even unnatural when viewed through the lens of neuroscience. Gradient backpropagation, for example, has powered much of early AI progress, yet its plausibility as a true mechanism for intelligence remains questionable, there is little evidence that the brain learns this way. In contrast, the biological foundations of learning are firmly rooted in Hebbian plasticity [

8], engram cell formation [

9], and synaptic potentiation [

10], mechanisms that are largely disconnected from backpropagation. The QF2 learning framework presented here is built directly on these neuroscientific principles, offering both theoretical justification and practical demonstration for a more brain-like method of knowledge acquisition. Moreover, architectural tricks popular in deep learning, such as residual connections and GELU activations, while effective in engineering terms, may actually hinder progress toward truly human-like AI. Our findings suggest that removing these components and embracing more biologically inspired mechanisms can open a more principled path toward next-generation, brain-inspired artificial intelligence.

QF2 learning bridges the query and the desired answer Y* directly through the weight update ΔW. Crucially, the instruct phase must first generate and store the correct answer, analogous to the formation of an engram cell in the brain. Equally important, the subsequent QF-update phase serves as a form of “review” or rehearsal after instruction, the model is presented only with the query X, and through Equation (2), the direct association between X and Y* is established. This review step is essential: just as a student consolidates new knowledge by practicing recall after being taught, the model uses the QF-update phase to form a robust, one-shot connection between query and answer. This mechanism also ensures that newly acquired knowledge is not inappropriately generalized to unrelated queries; only the intended association is formed. The steep sigmoid used in Equation (3) is essential for this process, enforcing near-binary (0 or 1) activations akin to neuronal firing, while Equation (4) ensures that each activation bias update incrementally shifts Y toward the desired Y* 0/1 firing pattern. Notably, both QF and QF2 feedforward learning can accurately predict rare or previously unseen facts (such as “Oxinnovate’s CEO is Qi,” rather than any other token), highlighting that the information content embedded in the feedforward ΔW update can be similar or even the same as that obtained through traditional gradient backpropagation or QF matrix inversion. Furthermore, this QF2 quick firing connection mechanism may offer a promising framework for future brain–machine interface approaches, providing a biologically inspired method for linking neural activity with artificial systems.

5. Conclusions

Quick Firing (QF2) learning not only provides a theoretical and mathematical foundation for direct, firing-based synaptic weight updates, but also demonstrates their practical feasibility with open-source code and reproducible experiments. This approach marks a significant step toward more human-like learning in AI, laying the groundwork for efficient, interpretable, and biologically inspired knowledge acquisition in future intelligent systems.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix A: Implementation Details

Figure A1.

QF2 Learning Workflow and Implementation Details.

Figure A1.

QF2 Learning Workflow and Implementation Details.

This figure illustrates the workflow of QF2 learning and demonstrates how fine-grained, brain-inspired knowledge consolidation can be achieved in large language models. The qfsignificance vector allows direct control over the learning strength of each token, effectively simulating human-like selective attention and prioritization, for example, important tokens can be assigned higher values, while unimportant ones are set to zero. The global learning rate parameter qflr adjusts the overall learning efficiency. Such mechanisms mirror aspects of human cognition, where the importance or emotional salience of information modulates the intensity of learning.

The QF-infer-wp mode loads the updated weights W’ after learning, enabling the model to recall newly acquired knowledge without explicit instruction. The function calc_this_w_prime computes the new weight matrix W’ from the stored input–output pairs (X, Y*), as produced in the QF-instruct and QF-update phases. Together, these components enable precise, one-shot, and interpretable weight updates, closely mimicking synaptic modifications in biological neural systems.

Appendix B: Code and Data Availability

The company fact training dataset used in our experiments can be found at

All code and models are released under open-source licenses to facilitate reproducibility and further research.

References

- Lillicrap, Timothy P., et al. "Backpropagation and the brain." Nature Reviews Neuroscience 21.6 (2020): 335-346.

- Nair, Vinod, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. "Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines." Proceedings of the 27th international conference on machine learning (ICML-10). 2010.

- He, Kaiming, et al. "Deep residual learning for image recognition." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

- Achiam, Josh, et al. "Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

- Qi, Feng. "QF: Quick Feedforward AI Model Training without Gradient Back Propagation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2507.04300 (2025).

- Team, Qwen. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2412.15115 (2024).

- LeCun, Yann, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. "Deep learning." nature 521.7553 (2015): 436-444.

- Hebb, Donald Olding. The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. Psychology press, 2005.

- Kitamura, Takashi, et al. "Engrams and circuits crucial for systems consolidation of a memory." Science 356.6333 (2017): 73-78.

- Malenka, Robert C., and Mark F. Bear. "LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches." Neuron 44.1 (2004): 5-21.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).