Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Biochemical and Immunological Analyses

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

3.2. Correlations Between NGAL and Various Clinical and Biochemical Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.R.; Fatoba, S.T.; Oke, J.L.; Hirst, J.A.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Lasserson, D.S.; Hobbs, F.R. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease–a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: An international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetterstrand, V.J.R.; Schultz, M.; Kallemose, T.; Torre, A.; Larsen, J.J.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Brandi, L. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a single test rule out biomarker for acute kidney injury: A cross-sectional study in patients admitted to the emergency department. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virzì, G.M.; Morisi, N.; Oliveira Paulo, C.; Clementi, A.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin: Biological Aspects and Potential Diagnostic Use in Acute Kidney Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romejko, K.; Markowska, M.; Niemczyk, S. The review of current knowledge on neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, L.; Johnsen, A.H.; Sengeløv, H.; Borregaard, N. Isolation and primary structure of NGAL, a novel protein associated with human neutrophil gelatinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 10425–10432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Rubin, J.; Han, W.; Venge, P.; Xu, S. The origin of multiple molecular forms in urine of HNL/NGAL. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 2229–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Bourgonje, M.F.; Kieneker, L.M.; la Bastide-Van Gemert, S.; Gordijn, S.J.; Hidden, C.; Nilsen, T.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Mulder, D.J. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin associates with new-onset chronic kidney disease in the general population. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation, N.K. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 60, 850–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, A.A.; Neilson, E.G. Chronic kidney disease progression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 2964–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft, D.W.; Gault, H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976, 16, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D.; Group*, M.o.D.i.R.D.S. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Greene, T.; Stevens, L.A.; Zhang, Y.; Hendriksen, S.; Kusek, J.W.; Van Lente, F.; Collaboration*, C.K.D.E. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro III, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A.; Rosner, M.H. Drug-induced acute kidney injury. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obert, L.A.; Elmore, S.A.; Ennulat, D.; Frazier, K.S. A review of specific biomarkers of chronic renal injury and their potential application in nonclinical safety assessment studies. Toxicol. Pathol. 2021, 49, 996–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Mora Sánchez, M.G.; Bernal Amador, A.S.; Paniagua, R. The Metabolism of Creatinine and Its Usefulness to Evaluate Kidney Function and Body Composition in Clinical Practice. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J.; Warnock, D.G.; Delanaye, P. The global burden of chronic kidney disease: Estimates, variability and pitfalls. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Hur, M. New Issues With Neutrophil Gelatinase-associated Lipocalin in Acute Kidney Injury. Ann. Lab. Med. 2023, 43, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Somma, S.; Magrini, L.; De Berardinis, B.; Marino, R.; Ferri, E.; Moscatelli, P.; Ballarino, P.; Carpinteri, G.; Noto, P.; Gliozzo, B. Additive value of blood neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin to clinical judgement in acute kidney injury diagnosis and mortality prediction in patients hospitalized from the emergency department. Crit. Care 2013, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Shengbu, M.; Shi, Q.; Jiaqiu, S.; Lai, X. Biomarkers: New Advances in Diabetic Nephropathy. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578X251321758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Behera, M.; Rai, M.; Mishra, P.; Bhaduaria, D.; Yadav, S.; Agarwal, V.; Karoli, R.; Prasad, N.; Gupta, A. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: As a predictor of early diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Nephrol 2018, 28, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, P.; Dahiya, K.; Bansal, A.; Vashist, S.; Dokwal, S.; Prakash, G. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) as a potential early biomarker for diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolignano, D.; Lacquaniti, A.; Coppolino, G.; Donato, V.; Fazio, M.R.; Nicocia, G.; Buemi, M. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as an early biomarker of nephropathy in diabetic patients. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2009, 32, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; He, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Lu, R.; Gao, W. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) is an early biomarker for renal tubulointerstitial injury in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 123, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; Shin, N.; Shin, M.J.; Yang, B.Y.; Kim, I.Y.; Song, S.H.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, S.B.; Kwak, I.S.; Seong, E.Y. High serum and urine neutrophil gelatinaseassociated lipocalin levels are independent predictors of renal progression in patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Wu, S.; Yao, G.; Li, K.; Wang, D.; Xu, Y.; Feng, R. Lipocalin-2 exacerbates lupus nephritis by promoting Th1 cell differentiation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 2263–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, M.; Tölle, M.; van der Giet, M. High-density lipoprotein: Structural and functional changes under uremic conditions and the therapeutic consequences. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015, 423–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gubina, N.V.; Kupnovytska, I.H.; Romanyshin, N.M.; Mishchuk, V.H. Lipocalin level and indicators of lipid metabolism in the initial stages of chronic kidney disease against the background of obesity. Clin. Pract. 2023, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Viau, A.; El Karoui, K.; Laouari, D.; Burtin, M.; Nguyen, C.; Mori, K.; Pillebout, E.; Berger, T.; Mak, T.W.; Knebelmann, B. Lipocalin 2 is essential for chronic kidney disease progression in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 4065–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danquah, M.; Owiredu, W.K.; Jnr, B.E.; Serwaa, D.; Odame Anto, E.; Peprah, M.O.; Obirikorang, C.; Fondjo, L.A. Diagnostic value of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as an early biomarker for detection of renal failure in hypertensives: A case–control study in a regional hospital in Ghana. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Fan, P.; Huang, B.; Deng, H.B.; Cheung, B.M.Y.; Félétou, M.; Vilaine, J.P.; Villeneuve, N.; Xu, A.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Deamidated lipocalin-2 induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in dietary obese mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courbon, G.; Francis, C.; Gerber, C.; Neuburg, S.; Wang, X.; Lynch, E.; Isakova, T.; Babitt, J.L.; Wolf, M.; Martin, A. Lipocalin 2 stimulates bone fibroblast growth factor 23 production in chronic kidney disease. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Li, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, M.; Ma, Y.; Cong, B. NGAL protects against endotoxin-induced renal tubular cell damage by suppressing apoptosis. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steflea, R.M.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Aburel, O.; Horhat, F.G.; Vlad, S.V.; Bratosin, F.; Banta, A.M.; Doros, G. Evaluating Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Pediatric CKD: Correlations with Renal Function and Mineral Metabolism. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 1099–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Group 1 (n=16) |

Group 2 (n=33) |

Group 3 (n=22) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female (n/n) | 5/11 | 23/10 | 11/11 | |

| Age (years) 1 | 48.81 ± 16.97 | 67.03 ± 9.69 | 68.09 ± 11.48 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min) 1 | 102.31 ± 11.75 | 60.94 ± 11.61 | 25.82 ± 9.71 | <0.001 |

| SCr (µmol/L) 2 | 61.00 (59.25-78.75) | 105.00 (91.50-131.50) | 244.00 (164.50-281.25) | <0.001 |

| UA (µmol/L) 1 | 275.00 ± 80.73 | 340.15 ± 71.44 | 351.86 ± 78.62 | 0.010 |

| Ca (mmol/L) 1 | 2.42 ± 0.11 | 2.39 ± 0.09 | 2.32 ± 0.15 | 0.029 |

| Pi (mmol/L) 1 | 1.11 ± 0.15 | 1.15 ± 0.20 | 1.28 ± 0.27 | 0.041 |

| PTH (pg/mL) 2 | 21.77 (17.89-34.92) | 29.10 (20.38-41.92) | 61.73 (32.80-130.80) | <0.001 |

| ALP (U/L) 1 | 74.38 ± 25.51 | 73.58 ± 19.79 | 94.32 ± 33.06 | 0.011 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) 2 | 1.50 (1.13-2.96) | 2.97 (2.31-5.60) | 3.72 (2.47-10.55) | 0.009 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) 2 | 1.50 (1.50-1.50) | 1.50 (1.50-3.21) | 3.08 (1.50-9.46) | 0.007 |

| WBC (G/L) 2 | 7.40 (5.70-10.40) | 7.85 (6.73-8.67) | 8.40 (7.10-10.15) | 0.340 |

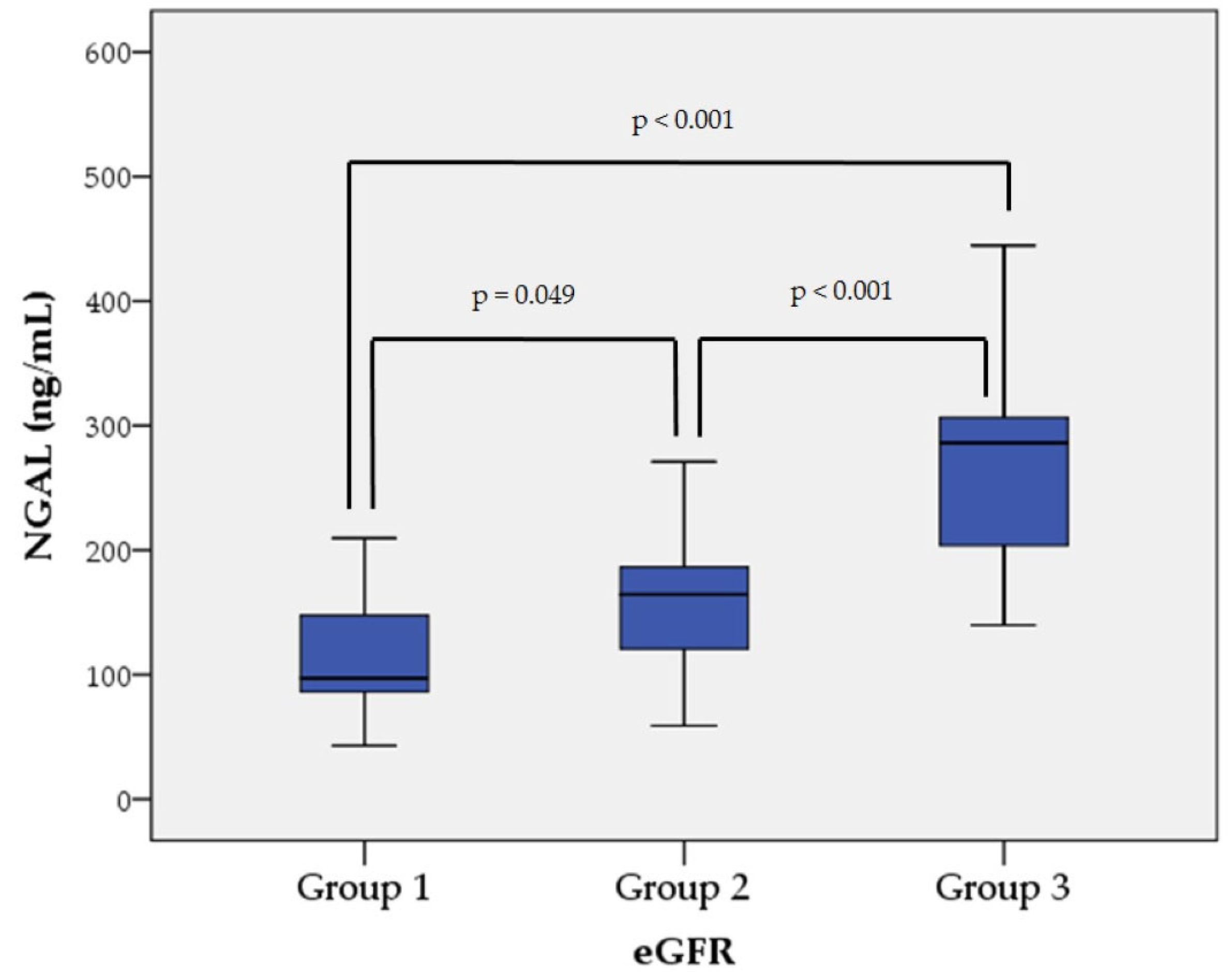

| NGAL (ng/mL) 1 | 113.40 ± 46.47 | 155.35 ± 50.18 | 267.80 ± 72.50 | <0.001 |

| Correlations | Correlation Coefficient |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| NGAL and Age | 0.284 * | 0.016 |

| NGAL and eGFR | –0.730 ** | <0.001 |

| NGAL and SCr | 0.736 ** | <0.001 |

| NGAL and UA | 0.260 * | 0.029 |

| NGAL and Ca | –0.334 ** | 0.004 |

| NGAL and Pi | 0.265 * | 0.025 |

| NGAL and PTH | 0.494 ** | <0.001 |

| NGAL and ALP | 0.370 ** | 0.001 |

| NGAL and hs-CRP | 0.334 ** | 0.004 |

| NGAL and IL-6 | 0.509 ** | <0.001 |

| NGAL and WBC | 0.362 ** | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).