Submitted:

26 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

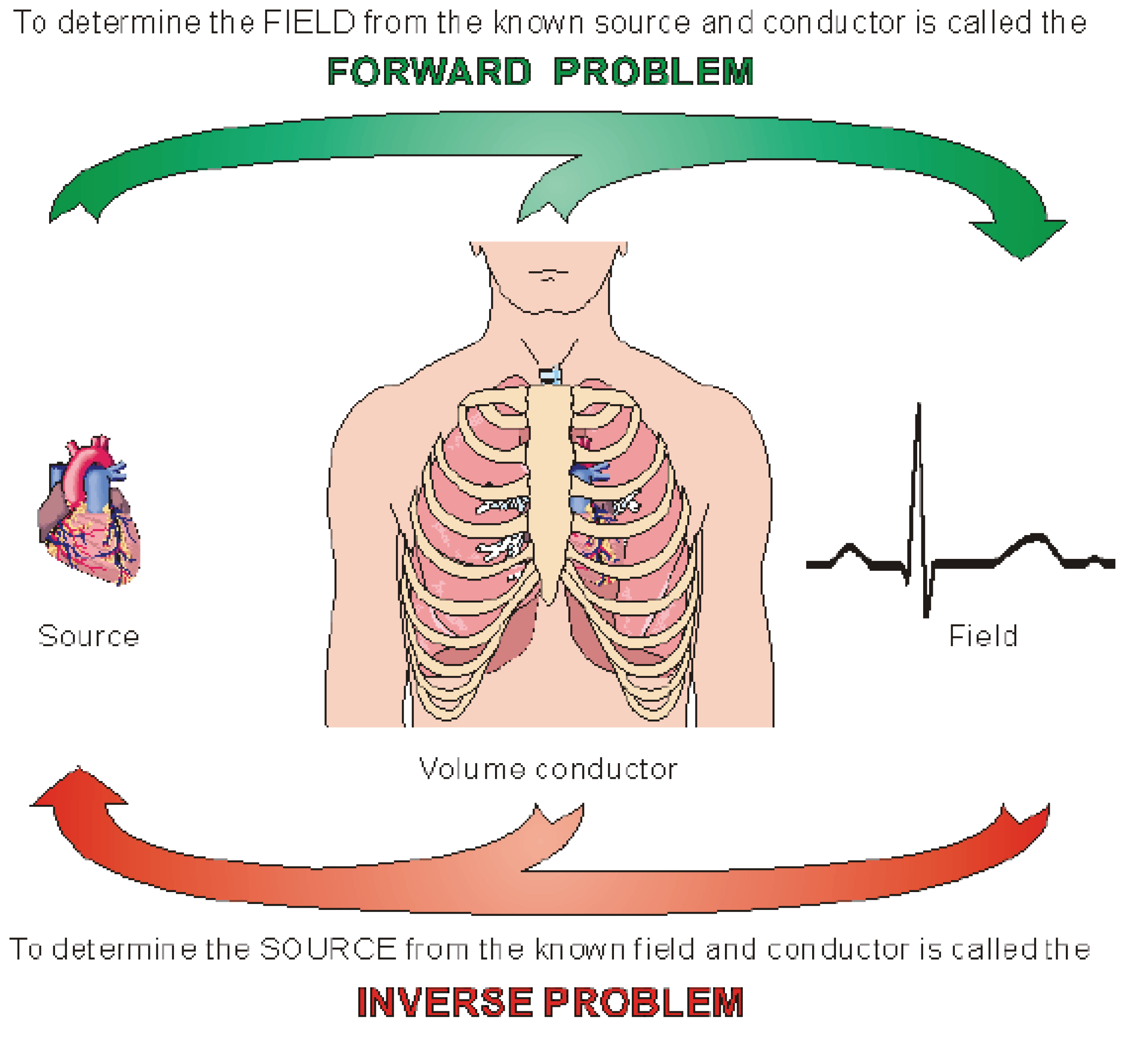

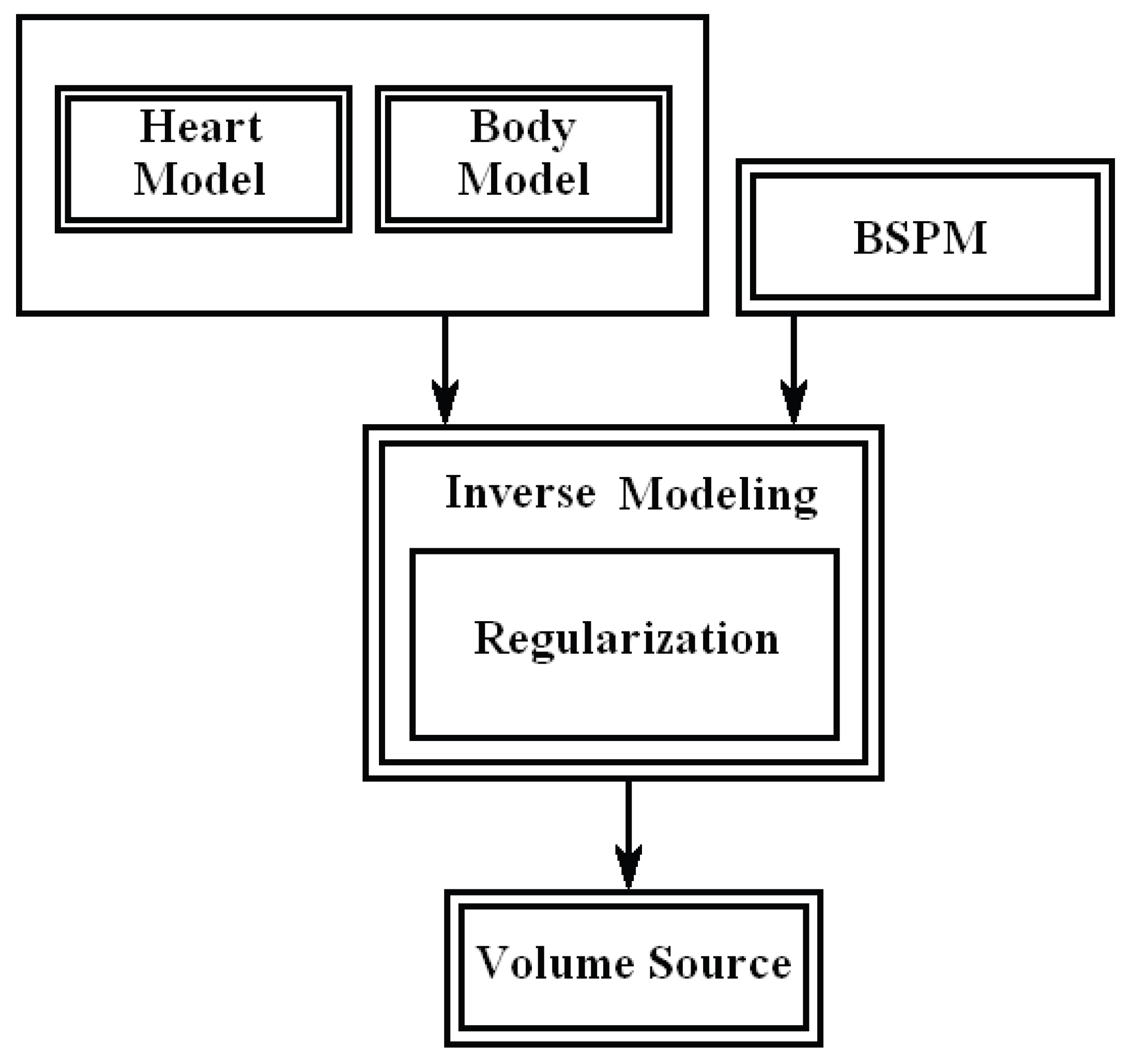

1. Introduction

2. Transfer Matrix of Isotropic Volume Source in Infinite Homogeneous Volume Conductor

3. Transfer Matrix of Anisotropic Volume Source in Infinite Homogeneous Volume Conductor

4. Transfer Matrix of a Volume Source in Inhomogeneous Volume Conductor

- 1-

- Compute the transfer matrix A of the organ or the body torso to all sources inside the heart using Equation 13. (Equation 9 can be used also in case of no information about fibers directions).

- 2-

- Tessellate the organ’s surface into triangular elements and calculate the normal vectors on each surface element done by cross product of any two edges of the triangle in anti-clock-wise direction and calculate the area of the triangle element can be derived from the dot product of two these edges.

- 3-

- From each point on the body surface, compute the vector r to a point on an organ surface element.

- 4-

- Compute the scalar

- 5-

- Multiply the last scalar by the corresponding row (the row of the current observation point) in the corresponding A matrix, and add this row in a new matrix .

5. Conclusions

References

- Malmivuo, J.; Plonsey, R. Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields, 1st ed.; Oxford Univ. Press, 1995; ISBN 0195058232. [Google Scholar]

- Nenonen, J.; Purell, C.J.; Horacek, B.M.; Stroink, G.; Katila, T. Magnetocardiographic functional localization using a current dipole in a realistic torso. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1991, 38, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C.J.; Stroink, G. Moving dipole inverse solutions using realistic torso models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1991, 38, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.A.; Brauer, F.; Stroink, G.; Purcell, C.J. The effect of measurement conditions on MCG inverse solutions. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1992, 39, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seger, M. Modeling the Electrical Function of the Human Heart. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, D.H.; MacLeody, R.S. Electrical Imaging of the Heart: Electrophysical Underpinnings and Signal Processing Opportunities. IEEE Signal Processing 1996, 14, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintermuller, C. Development of a Multi-Lead ECG Array for Noninvasive Imaging of the Cardiac Electrophysiology. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Messinger-Rapport, B.J.; Rudy, Y. Noninvasive recovery of epicardial potentials in a realistic heart- torso geometry. Normal sinus rhythm. American Heart Association 1990, 66, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Oster, H.S.; Taccardi, B.; Lux, R.L.; Ershler, P.R.; Rudy, Y. Electrocardiographic Imaging : Noninvasive Characterization of Intramural Myocardial Activation From Inverse-Reconstructed Epicardial Potentials and Electrograms. American Heart Association 1998, 97, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Fischer, G.; Pfeifer, B.; Modre, R.; Hanser, F.; Roithinger, F.X.; Stuehlinger, M.; Pachinger, O.; Hintringer, F. Single-Beat Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology of Ventricular Pre-Excitation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. Non-Invasive Electrical Imaging of the Heart. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, New Zealand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, C.; Jia, P.; Ghanem, R.; Calvetti, D.; Rudy, Y. Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI):Application of the Generalized Minimal Residual (GMRes) Method. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 31, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, R.N.; Ramanathan, C.; Ryu, K.; Markowitz, A.; Rudy, Y. Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI): Comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients. Heart Rhythm. 2005, 2, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intini, R.; Goldstein, R.; Jia, P.; Ramanathan, C.; Stambler, B.S.; Rudy, Y.; Waldo, A.L. A novel diagnostic modality used for mapping of focal left ventricular tachycardia in a young athlete. Heart Rhythm. 2005, 2, 1250–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Rudy, Y. Electrocardiographic imaging of cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: Observation of variable electrophysiologic responses. Heart Rhythm. 2006, 3, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, R.N.; Ramanathan, C.; Jia, P.; Rudy, Y. Heart-Surface Reconstruction and ECG Electrodes Localization Using Fluoroscopy, Epipolar Geometry and Stereovision:Application to Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrical Activity. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2003, 22, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Hintringer, F.; Fischer, G. Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology. Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal 2007, 7, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, C.; Ghanem, R.N.; Jia, P.; Ryu, K.; Rudy, Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2004, 10, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rudy, Y. Accuracy of Quadratic Versus Linear Interpolation in Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI). Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 33, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seger, M.; Modre, R.; Pfeifer, B.; Hintermuller, C.; Tilg, B. Non-invasive Imaging of Atrial Flutter. Computers in Cardiology 2006, 33, 601–604. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ramachandra, I.; Liu, Z.; Muneer, B.; Pogwizd, S.M.; He, B. Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005, 289, H2724–H2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthis, C.G.; Bonovas, P.M.; Kyriacou, G.A. Inverse Problem of ECG for Direrent Equivalent Cardiac Sources. PIERS Online 2007, 3, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Li, G.; Zhang, X. Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Transmembrane Potentials Within Three-Dimensional Myocardium by Means of a Realistic Geometry Anisotropic Heart Model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 50, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Wu, D. Imaging and Visualization of 3-D Cardiac Electric Activity. IEEE Tran. Inf Tech. Biomed. 2001, 5, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Lian, J.; He, B. Noninvasive Localization of the Site of Origin of Paced Cardiac Activation in Human by Means of a 3-D Heart Model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 50, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; He, B. Noninvasive Reconstruction of Three-Dimensional Ventricular Activation Sequence From the Inverse Solution of Distributed Equivalent Current Density. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2006, 25, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Three-Dimensional Cardiac Electrical Imaging From Intracavity Recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of realistic heart electrical excitation based on DTI scans and modified reaction diffusion equation. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2018, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aff, I.A.I. Extraction of human heart conduction network from diffusion tensor MRI. The 7th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, 217–222.

- Elaff, I. Modeling of the Human Heart in 3D Using DTI Images. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2025, 15, 2450–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling the Human Heart Conduction Network in 3D using DTI Images. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2025, 15, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of realistic heart electrical excitation based on DTI scans and modified reaction diffusion equation. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2018, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of The Excitation Propagation of The Human Heart. World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences 2025, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Effect of the material properties on modeling of the excitation propagation of the human heart. World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences 2025, 22, 088–094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of 3D Inhomogeneous Human Body from Medical Images. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2025, 15, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of the Body Surface Potential Map for Anisotropic Human Heart Activation. Research Square 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Marqui, R.D. Review of Methods for Solving the EEG Inverse Problem. Intr. J. Bioelectromagnetism 1999, 1, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, R.S.; Brooks, D.H. Recent Progress in Inverse Problems in Electrocardiology; University of Utah, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, M. The Department of Computational and Applied Mathematics; University of Münster, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui, R.D.; Michel, C.M.; Lehman, D. Low resolution electromagnetic tomography: A new method for localizing electrical activity in the brain. Inter. J. of Psych 1994, 18, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).