Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Outline

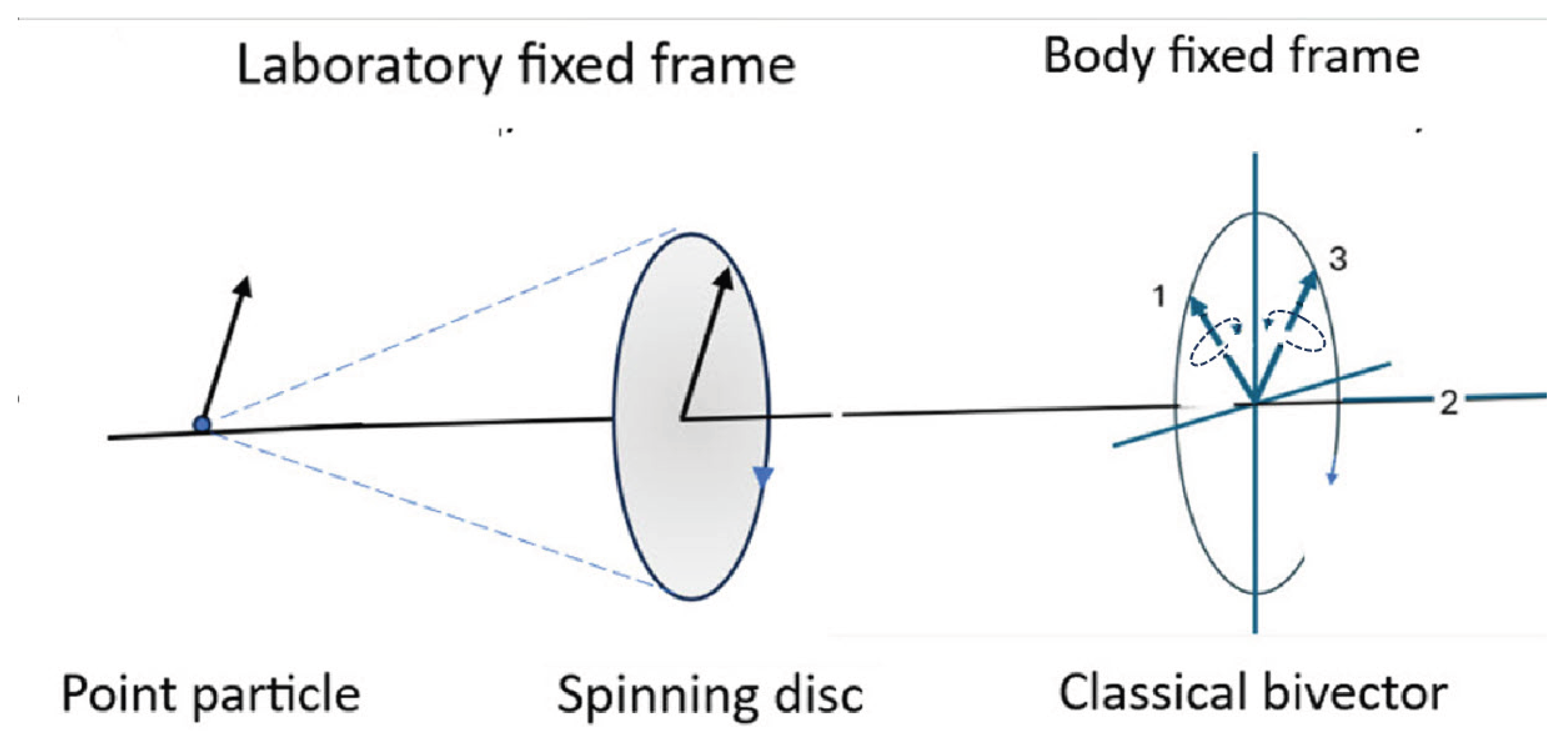

2. Classical Spin

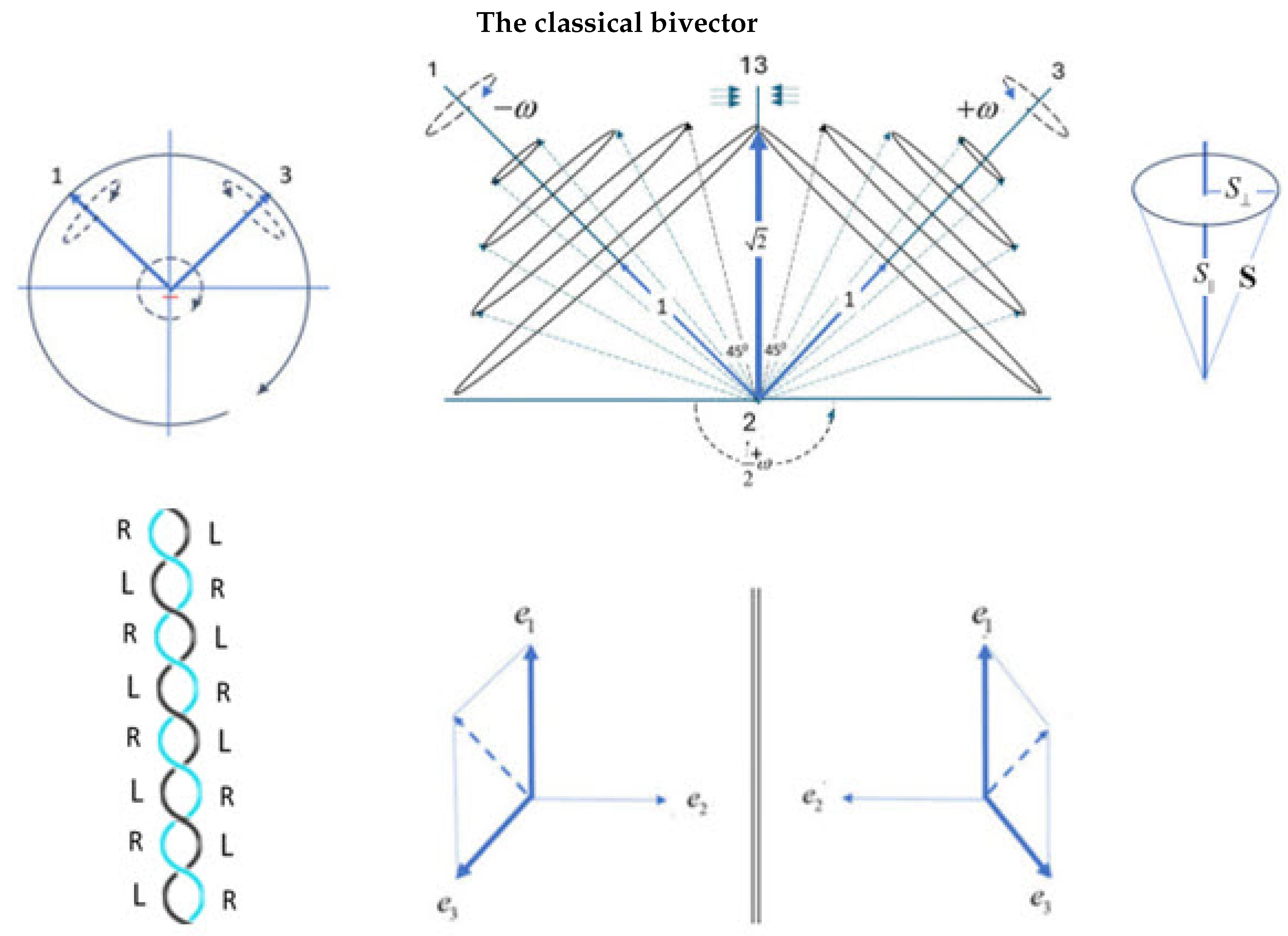

2.1. A Classical Bivector

2.2. Complementarity

2.3. Euler’s Equations

2.4. Resonance

2.5. Geometric Algebra: Bivector Dynamics

2.6. A Classical Boson of spin-1

2.7. Special Relativity

2.7.1. The Quantum and Relativistic Limits

3. Correspondence

3.1. Parity from Reflection

3.2. Classical-Quantum Correspondence

3.2.1. Calculation of Planck’s constant

3.3. Quaternion spin

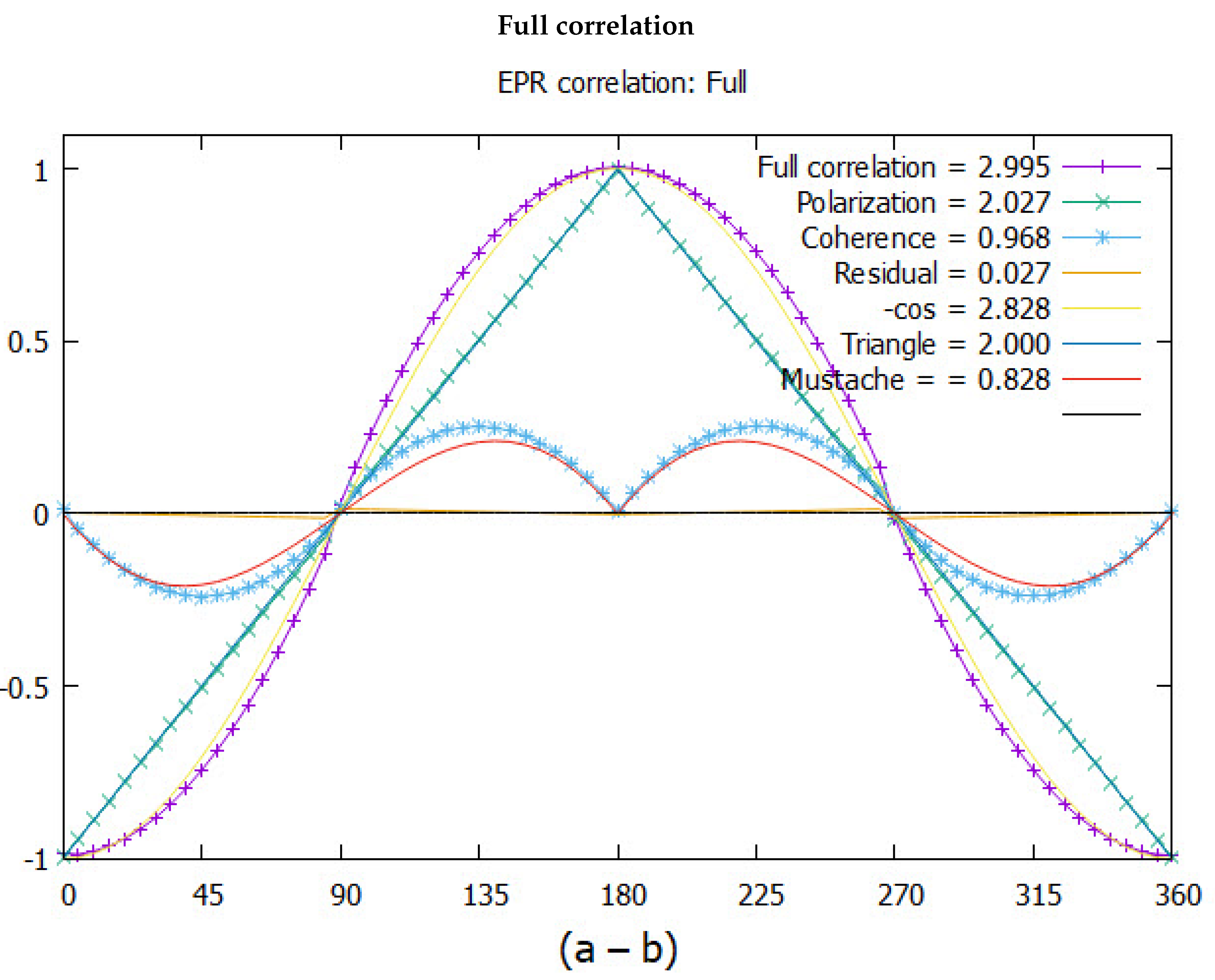

3.3.1. The EPR Paradox

4. Interpretation

4.1. Hammers, Wrenches, and Matter

4.2. Determinism

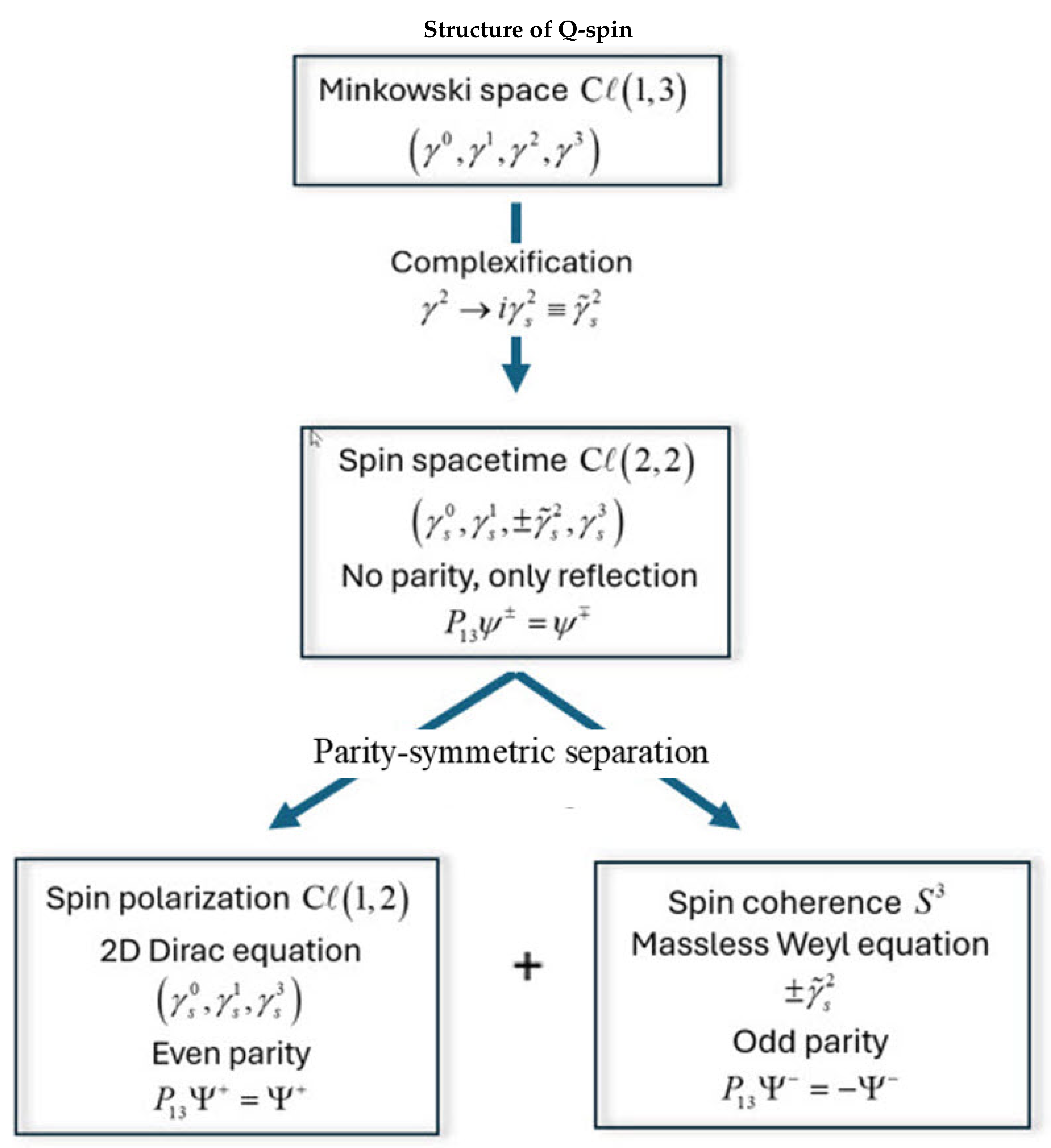

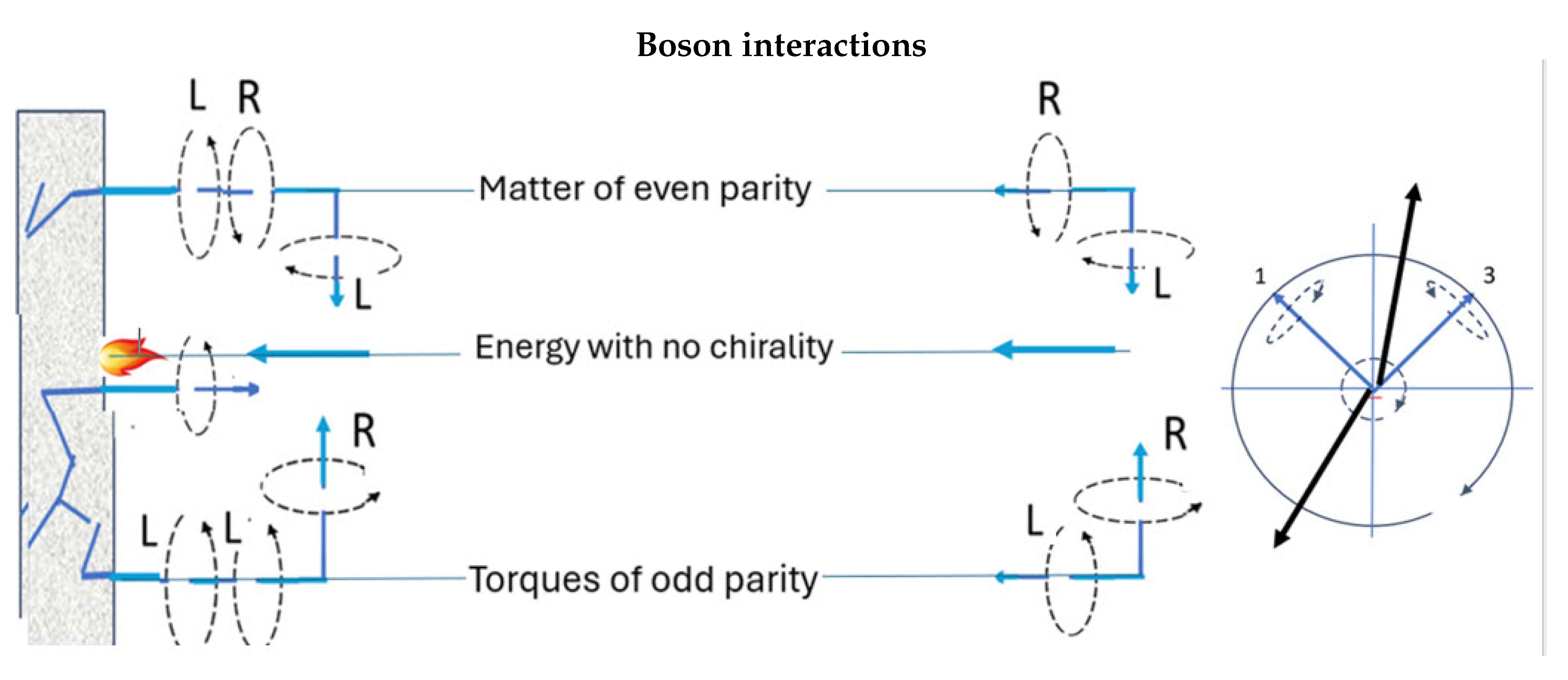

5. Unification of Bosons and Fermions

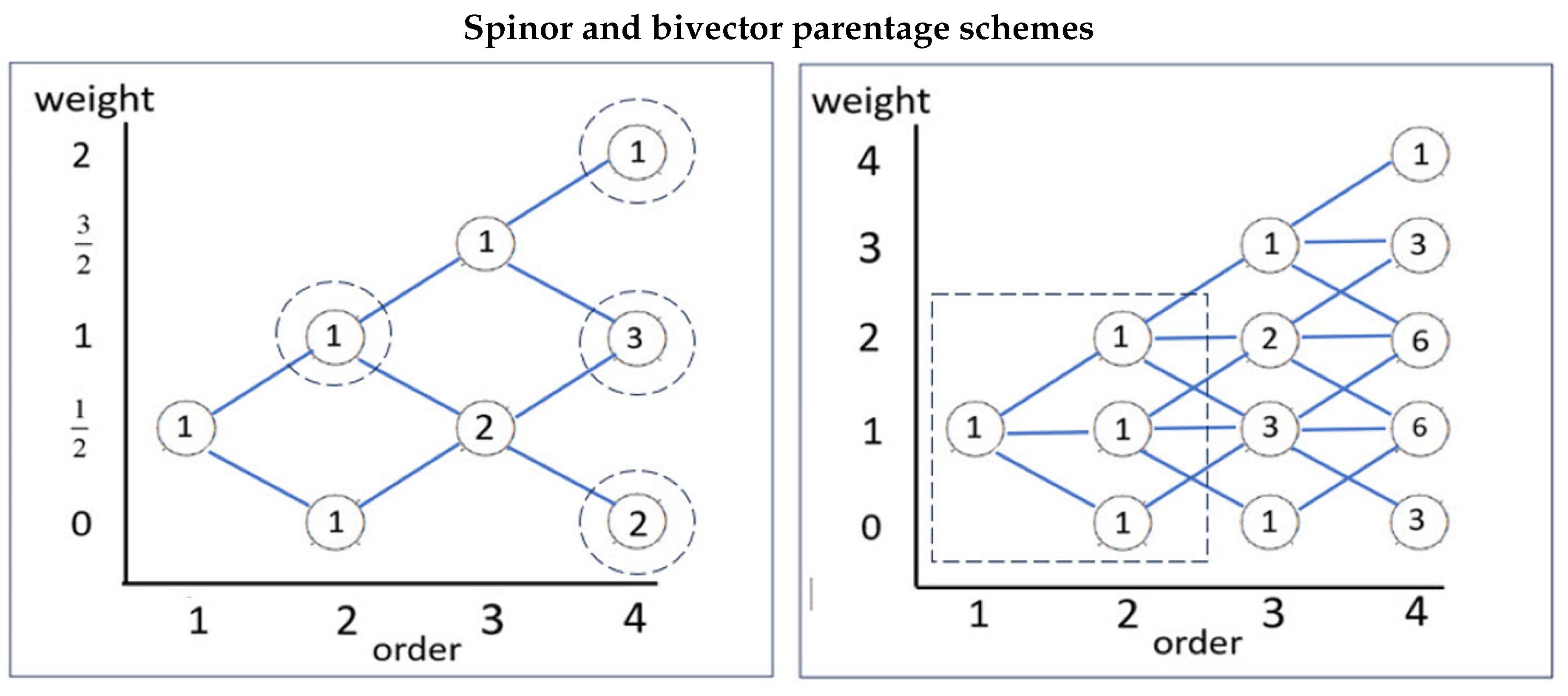

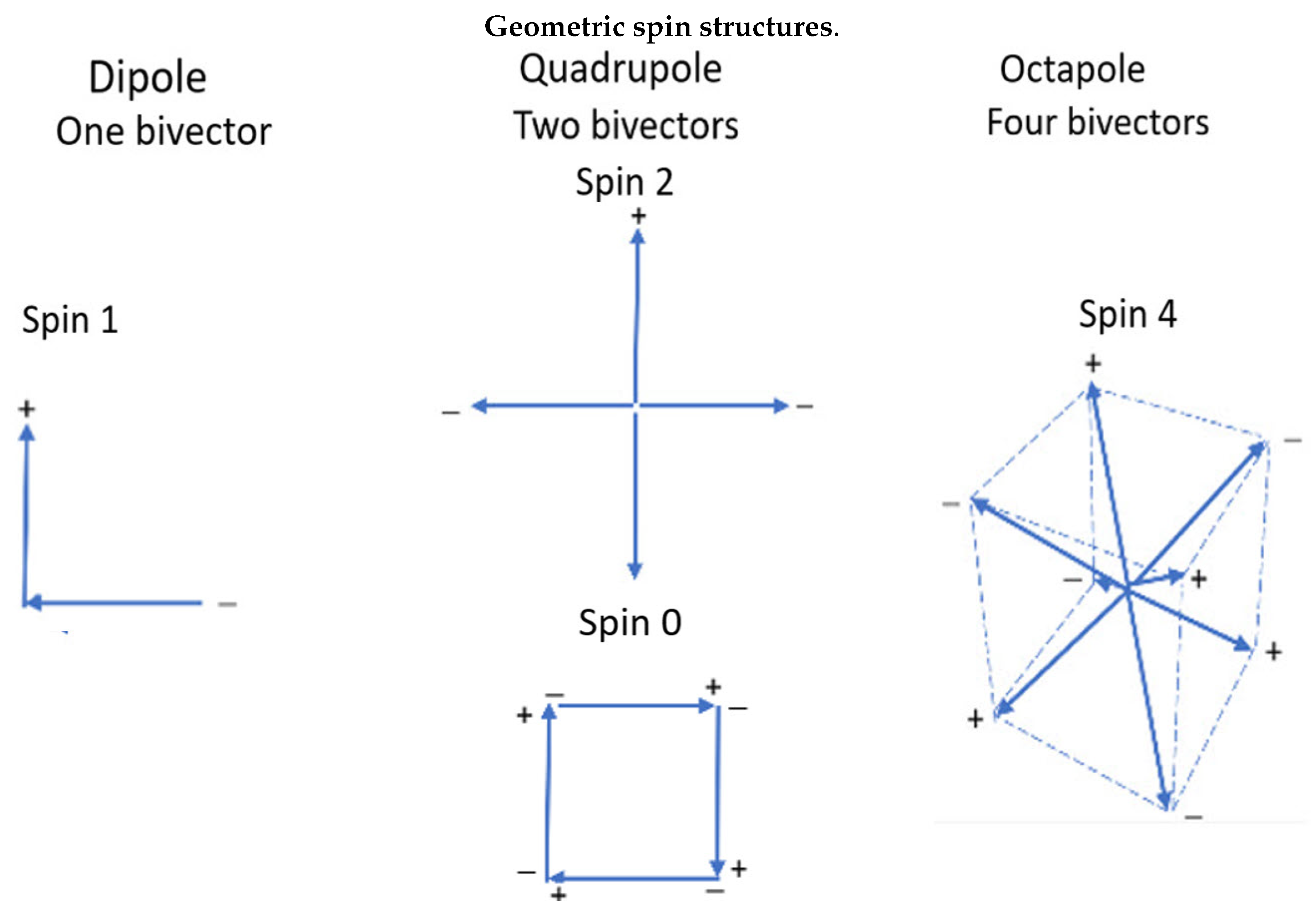

5.1. Emergence of Spin

5.2. Emergence of charge

5.3. Internal Mass-Energy

5.4. Photons Are Massless Bivectors

6. Ontology and Geometry

6.1. Particles

6.2. Lie versus Clifford Algebra

6.3. The Bivector Field

7. Quantization and Measurement

7.1. Lagrangians

7.2. Quantization

7.3. No Superposition; no Collapse

7.4. The Fermion Approximation

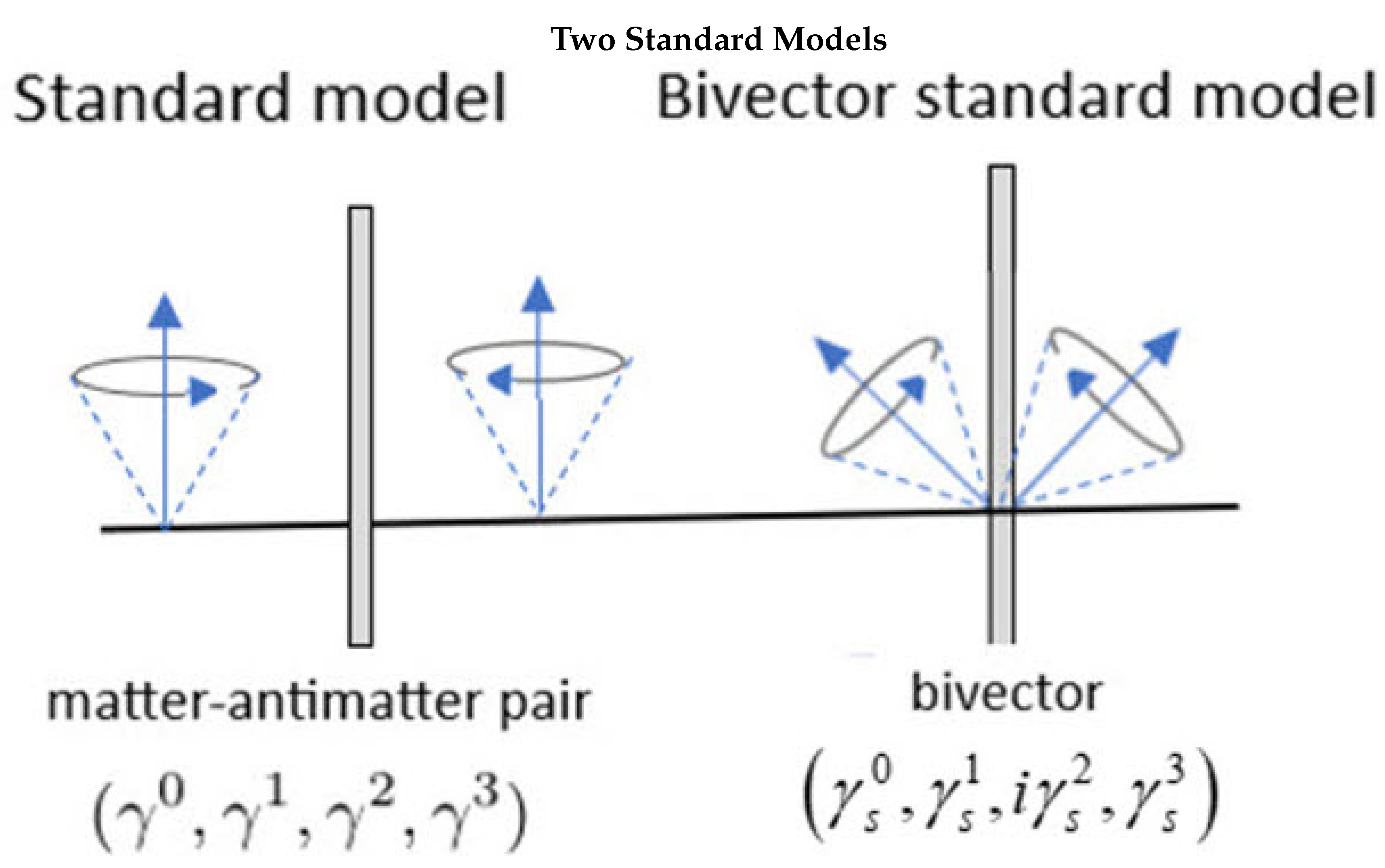

8. SM—BiSM and experiment

8.1. The “Origin of Positrons in the Galaxy” Puzzle

8.2. Separating Vector and Bivector Motion

8.3. Low Energy Studies

8.4. Neutrinos, Parity and Non-Locality

8.5. Classical Bivector

F. The Muon Anomaly

8.6. Electron quadrupole moment

8.7. Problems with chirality

9. Conclusions

A. Symmetry of Quaternion Spin

Appendix A Parentage Schemes

Appendix B Quantum Correspondence

Appendix C Symmetry of Quaternion Spin

References

- Peskin, M.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction To Quantum Field Theory; Frontiers in Physics: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The quantum theory of the electron. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, 1928; 117, 610–624. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctuary, B. Quaternion Spin. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. Spin Helicity and the Disproof of Bell’s Theorem. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. EPR Correlations Using Quaternion Spin. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6(3), 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, C.; Lasenby, J. Geometric algebra for physicists; Cambridge University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. A Theory of Electrons and Protons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1930, 126(801), 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, W. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics-Wave Equations; SpringerVerlag: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 310–360. [Google Scholar]

- Paganini, P. Fundamentals of particle physics: understanding the standard model; Cambridge University Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nuclear Physics 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzaglia, W.M. Physical applications of a generalized Clifford calculus (Papapetrou equations and metamorphic curvature). arXiv 1997, preprint gr-qc/9710027.

- Hestenes, D. Spin and uncertainty in the interpretation of quantum mechanics. American Journal of Physics 1979, 47, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D.; Sobczyk, G. Clifford algebra to geometric calculus: a unified language for mathematics and physics (Vol. 5); Springer Science and Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C.; Sen, S. Topology and geometry for physicists; Elsevier, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A.S. Quantum field theory and topology (Vol. 307); Springer Science and Business Media: 2013.

- Hestenes, D. The zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics. Foundations of Physics 1990, 20(10), 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidhar, K. The spin bivector and zeropoint energy in geometric algebra. Adv. Studies Theor. Phys 2012, 6, 675–686. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H. Classical mechanics; Pearson Education India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.M. Spacetime and geometry; Cambridge University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, I.E.; Lewis, J.E. Geometry of convex sets; John Wiley and Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger, H. Minkowskische addition und subtraktion beliebiger punktmengen und die theoreme von erhard schmidt. Mathematische Zeitschrift 1950, 53(3), 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics Physique Fizika 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics; Cambridge University Press: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, N.; Cavalcanti, D.; Pironio, S.; Scarani, V.; Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Reviews of modern physics 2014, 86(2), 419–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Physical review letters 1969, 23(15), 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Dalibard, J.; Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Physical review letters 1982, 49, 1804.Aspect, A. Proposed experiment to test the non separability of quantum mechanics. Physical Review D 1976, 14, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G.; Jennewein, T.; Simon, C.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Physical Review Letters 1998, 81(23), 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, H.M. The two Bell’s theorems of John Bell. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 2014, 47, 424001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczynski, M. Quantum nonlocality: how does nature do it? Entropy 2024, 26(3), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Quantum mechanics of fractional-spin particles. Physical review letters 1982, 49(14), 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrennikov, A. Contextual approach to quantum mechanics and the theory of the fundamental prespace. arXiv 2003, preprint quant-ph/0306003.

- Khrennikov, A. Y. Contextual approach to quantum formalism (Vol. 160); Springer Science & Business Media: 2009.

- Hestenes, D.; Lasenby, A. Space-time algebra; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2015; p. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, M.V. (1984). Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1802, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Oveshnikov, L. N., Kulbachinskii, V. A., Davydov, A. B., Aronzon, B. A., Rozhansky, I. V., Averkiev, N. S., ...; Tripathi, V. Berry phase mechanism of the anomalous Hall effect in a disordered two-dimensional magnetic semiconductor structure. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrynnikov, N. R.; Sanctuary, B. C. Geometric phase in NMR interferometry experiment. Molecular Physics 1994, 83(6), 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. Quantum electrodynamics. I. A covariant formulation. Physical Review 1948, 74(10), 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P. Space-time approach to quantum electrodynamics. In Quantum Electrodynamics; CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, F. J. The Radiation Theories of Tomonaga, Schwinger, and Feynman. Phys. Rev. 1949, 75, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.,; Low, F. E. Quantum electrodynamics at small distances. Physical Review 1954, 95(5), 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. G. Renormalization group and critical phenomena. I. Renormalization group and the Kadanoff scaling picture. I. Renormalization group and the Kadanoff scaling picture. Physical review B 1971, 4(9), 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. G. , & Kogut, J. The renormalization group and the epsilon expansion. The renormalization group and the epsilon expansion. Physics reports 1974, 12(2), 75–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, D. J. Twenty five years of asymptotic freedom. Nuclear Physics B-Proceedings Supplements 1999, 74, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyuk, V. I.,; Sukhanov, A. D. Dirac in 20th century physics: a centenary assessment. Physics-Uspekhi 2003, 46, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, Bryan, "Qubits, Beta decay and Parity", 2025, In preparation.

- Coope, J. A. R.; Snider, R. F.; McCourt, F. R. Irreducible cartesian tensors. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1965, 43(7), 2269–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coope, J. A. R., and Snider, R. F. Irreducible cartesian tensors. II. General formulation. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1970, 11(3), 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coope, J. A. R. Irreducible Cartesian Tensors. III. Clebsch-Gordan Reduction. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1970, 11, 1591–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, R.F. Irreducible Cartesian Tensors (Vol. 43); Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kalb, M.; Ramond, P. Classical direct interstring action. Physical Review D 1974, 9(8), 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.D. Classical electrodynamics; John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauli_matrices.

- Frankel, T. The geometry of physics: an introduction; Cambridge university press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, L.H. Quantum field theory; Cambridge university press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, J. F.; Golowich, E.; Holstein, B. R. Dynamics of the standard model; Cambridge university press, 2014; p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctuary, B. Quaternion spin: parity and beta decay, 2025.

- Mohapatra, R.N.; Pal, P.B. Massive neutrinos in physics and astrophysics; World scientific, 2004; Vol. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Altarelli, G. The mystery of neutrino mixings. arXiv 2011, preprint arXiv:1111.6421.

- Born, M.; Oppenheimer, R. (2000). On the quantum theory of molecules. In Quantum Chemistry: Classic Scientific Papers (pp. 1-24).

- Donoghue, J. F.; Golowich, E.; Holstein, B. R. Dynamics of the standard model; Cambridge university press, 2014; p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- Zee, A. Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell; Princeton University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fano, U. Description of states in quantum mechanics by density matrix and operator techniques. Reviews of modern physics 1957, 29(1), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, John. Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics. Princeton university press, 1955.

- Wilde, M. M. (2013). Quantum information theory. Cambridge university press.

- Fields, B.; Sarkar, S. Big-bang nucleosynthesis (particle data group mini-review). arXiv 2006, preprint astro-ph/0601514.

- Peres, A. (Ed.). (2002). Quantum theory: concepts and methods. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Hu, X. M.; Guo, Y.; Liu, B. H.; Li, C. F.; Guo, G. C. Progress in quantum teleportation. Nature Reviews Physics 2023, 5(6), 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. H.; Brassard, G.; Crépeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W. K. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Physical review letters 1993, 70(13), 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. W. Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring,” in Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pp. 124–134, IEEE, 1994.

- Levitt, M. H. (2008). Spin dynamics: basics of nuclear magnetic resonance. John Wiley & Sons.

- Edmonds, A. R. (1996). Angular momentum in quantum mechanics (Vol. 4). Princeton university press.

- Guessoum, N.; Jean, P.; Gillard, W. The lives and deaths of positrons in the interstellar medium. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2005; 436, 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Weidenspointner, G.; Skinner, G.; Jean, P.; Knödlseder, J.; Von Ballmoos, P.; Bignami, G.; ...; Winkler, C. An asymmetric distribution of positrons in the Galactic disk revealed by gamma-rays. Nature, 2008; 451, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Beacom, J. F.; Bell, N. F.; Bertone, G. Gamma-ray constraint on Galactic positron production by MeV dark matter. Physical Review Letters 2005, 94(17), 171301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celso, J. Villas-Boas, Carlos E. Máximo, Paulo J. Paulino, Romain P. Bachelard, and Gerhard Rempe. ’Bright and Dark States of Light: The Quantum Origin of Classical Interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 134, 133603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, A. M. (2014). Quantum Measurements: a modern view for quantum optics experimentalists.

- Whitesides, G. M.; Grzybowski, B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 2002, 295(5564), 2418–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D. (2020). Introduction to elementary particles. John Wiley & Sons.

- Laurikainen, K. V. (2012). Beyond the atom: the philosophical thought of Wolfgang Pauli. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Wu, C. S.; Ambler, E.; Hayward, R. W.; Hoppes, D. D.; Hudson, R. P. Experimental test of parity conservation in beta decay. Physical review 1957, 105(4), 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M. W.; Manson, N. B.; Delaney, P.; Jelezko, F.; Wrachtrup, J.; Hollenberg, L. C. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Physics Reports 2013, 528(1), 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aylor, J. M.; Cappellaro, P.; Childress, L.; Jiang, L.; Budker, D.; Hemmer, P. R.; ...; Lukin, M. D. High-sensitivity diamond magnetometer with nanoscale resolution. Nature Physics 2008, 4(10), 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi, B.; Albahri, T.; Al-Kilani, S.; Allspach, D.; Alonzi, L. P.; Anastasi, A.; ...; Lusiani, A. Measurement of the positive muon anomalous magnetic moment to 0.46 ppm. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126(14), 141801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Asmussen, N.; Benayoun, M.; Bijnens, J.; Blum, T.; Bruno, M. .. ; Zhevlakov, A. S. The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon in the Standard Model. Physics reports 2020, 887, 1–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroi, T. Muon anomalous magnetic dipole moment in the minimal supersymmetric standard model. Physical Review D 1996, 53(11), 6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielse, G.; et al. New Determination of the Fine Structure Constant from the Electron g Value and QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. J. Mohr, B. N. Taylor, and D. B. Newell. CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATRIN Collaboration†, Aker, M., Batzler, D., Beglarian, A., Behrens, J., Beisenkötter, J.,; Zeller, G. Direct neutrino-mass measurement based on 259 days of KATRIN data. Science, 2025; 388, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi, K., Enomoto, S., Furuno, K., Goldman, J., Hanada, H., Ikeda, H., ...; (KamLAND Collaboration). First results from KamLAND: evidence for reactor antineutrino disappearance. Physical review letters 2003, 90, 021802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A. TASI 2020 lectures on precision tests of the standard model. arXiv 2020, preprint arXiv:2012.11642.

- Erler, J.; Schott, M. Electroweak precision tests of the Standard Model after the discovery of the Higgs boson. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 2019, 106, 68–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Myers, T.G.; Sukra, B.A.D.; Gabrielse, G. Measurement of the electron magnetic moment. Physical review letters 2023, 130(7), 071801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W.E.; Retherford, R.C. Fine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom by a Microwave Method. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H. B. G. On the Attraction Between Two Perfectly Conducting Plates. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 1948, 51, 793. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia: Physics beyond the Standard Model, accessed April 2025.

- "Interpretations of quantum mechanics," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, [Online]. Available: urlhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretations of quantum mechanics. [2025-04-05].

- Werner Heisenberg. Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1927, 43, 172–198. English translation: “The Physical Content of Quantum Kinematics and Mechanics,” in Quantum Theory and Measurement, edited by J. A. Wheeler and W. H. Zurek (Princeton University Press, 1983), pp. 62–8.

- Lee, T. D.; Yang, C. N. Question of parity conservation in weak interactions. Physical Review 1956, 104(1), 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Twistor algebra. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1967, 8, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Solutions of the Zero-Rest-Mass Equations. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1969, 10, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.C. Lie groups, Lie algebras, and representations. In Quantum Theory for Mathematicians; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 333–366. [Google Scholar]

- Howard Georgi – Lie Algebras in Particle Physics.

- Cornwell, J. F. (1984). Group theory in physics. Academic Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).