1. Introduction

The ovarian follicle is a dynamic entity with the potential to either progress towards ovulation or undergo atresia. Several factors contribute to the intricate process of ovarian function. These include the presence of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptors within small and developing follicles, the existence of luteinizing hormone (LH) receptors specifically in ovulatory follicles (OF), and the generation of growth factors by granulosa cells (GC) that play a pivotal role in influencing both follicular growth and the ovulation process [1-4]. Throughout the normal estrous cycle in bovine species, the ultimate dominant follicle experiences a process of differentiation. This differentiation facilitates the secretion of estradiol, initiating the preovulatory LH surge from the pituitary. Subsequently, this hormonal cascade leads to ovulation and the transformation of the remaining follicle into a corpus luteum [1-3].

In the stages of follicular growth and ovulation, steroidogenic cells, particularly GC, play a pivotal role in the maturation and release of the oocyte. Moreover, proliferation and function of GC are controlled by the regulation and transcription of different genes. This regulation plays a crucial role in normal follicular development, influencing the physiological state of the dominant preovulatory follicle. For instance, the transcription of genes governing the growth of a dominant follicle (DF) undergoes rapid downregulation or silencing in granulosa cells due to increased intracellular signaling mediated by LH [5-7]. In contrast, the preovulatory follicle exhibits a set of genes activated in response to the LH surge or hCG injection [8-10]. Among these genes, our previous studies identified TRIB2, a member of the Tribbles pseudokinase (TRIB) family, as differentially expressed in GC of DF and downregulated by hCG in OF [

11].

The TRIB family of serine/threonine pseudokinases is composed of TRIB1, TRIB2, and TRIB3, which represent atypical members of the serine/threonine kinase super family [

12]. Functionally, TRIB pseudokinases exhibit distinctive features, including a PEST domain in the N-terminal region that facilitates protein degradation. Additionally, they contain a pseudokinase domain, which is analogous to protein serine/threonine kinases but lacks catalytic activity [13, 14]. The presence of a constitutive photomorphogenesis 1 (COP1) site at the C-terminal region enables the targeted degradation of crucial proteins through the proteasome. Furthermore, there is a binding site for MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) Kinase 1 (MEK1), which plays a regulatory role in modulating MAPK activity [13, 15]. Therefore, TRIB family members can modulate the ubiquitin-proteasome system and stabilize protein substrates, as shown with TRIB3 [

16]. In this study, we used an

in vitro model of cultured granulosa cells along with the CRISPR/Cas9 approach to inhibit TRIB3 expression to better elucidate its function and mechanism of action in granulosa cells.

Overall, TRIB members function as important signaling mediators and scaffold subunits via the binding and modulation of several signaling molecules, including kinases, phosphatases, transcription factors and components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. In particular, TRIB3 can interact with ubiquitin ligase, proteasomal degradation systems, autophagy, transcription factors, MAPK/ERK, TGF-β, and JAG1/Notch signaling pathways [17-19]. Also, it is found that loss of TRIB2 in Drosophila leads to increased proliferation, while overexpression leads to a slowed cell cycle and altered fertility [19-21]. Molecular studies in bovine species have demonstrated the expression of TRIB members in granulosa cells of ovarian follicles during follicular development as well as a correlation between oocyte maturation and Tribbles expression [22, 23].

These reports indicate that TRIB members are involved in numerous cellular processes, including the expression of target genes in different cell types, such as reproductive cells. However, TRIB members functions and mode of action in GC of the ovarian follicles of mammals have not yet been fully investigated. In this study, an in vivo model of bovine follicles at different developmental stages as well as an in vitro model of cultured GC were used to decipher and better understand TRIB function and mode of action in reproductive cells. We hypothesized that TRIB members are regulated differently during follicular development and ovulation processes. We specifically aimed to investigate their regulation by gonadotropins FSH an LH and study their potential actions on target signaling pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

The experimental procedures underwent thorough review and received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee within the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Montreal (authorization# 21-Rech-1959). The cows received care and treatment in strict compliance with the guidelines outlined by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC, 2009) and according to ARRIVE guidelines.

To analyze the regulation and function of TRIB members in ovarian granulosa cells (GC), both in vivo and in vitro models were utilized.

2.2. In Vivo Sample Preparation

The in vivo model was prepared following previously established methods [23, 24].

Experimental animal model and

in vivo sample preparation including groups being compared and experimental unit have been previously described [23-25]. After synchronizing the estrous cycle through a single injection of PGF2α, normal cycling cows were assigned to two distinct groups: one comprising cows with dominant follicles (DF group, n=4) and another group consisting of cows with ovulatory follicles (OF group, n=4). The DF were surgically removed by ovariectomy from four cows on day 5 of the estrous cycle, using day 0 as a reference point corresponding to the day of estrus. In this context, the dominant follicle was identified with a diameter of ≥8mm, exhibiting growth, while subordinate follicles remained either in a static state or regressing [

11]. Follicular walls (FW) consisting of theca interna with attached mural GC were also prepared at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours post-hCG injection, with two cows (n=2) sampled per time point [

26]. The 0-hour sample was represented by day 7 dominant follicles. Immediately after ovariectomy, follicles were dissected to create preparations of granulosa cells from both DF and OF, as well as the follicular walls. These preparations were stored at -80°C until further analyses.

2.3. In Vitro Sample Preparation

Ovaries were obtained from the slaughterhouse, and GC were collected from follicles (<10 mm in diameter). GC were cultured in twelve-well plates (n=4 independent experiments, unless otherwise stated) for the analysis of protein expression. Culture media were prepared using McCoy’s 5a supplemented with L-glutamine (2mM), sodium bicarbonate (0.084%), bovine serum albumin (BSA; 0.2%), HEPES (20 mM), sodium selenite (4 ng/ml), transferrin (5μg/ml), insulin (10ng/ml), non-essential amino acids (1 mM), androstenedione (100 nM), penicillin (100 IU), and streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) [27, 28]. Cells were seeded at a density of 0.1×106 cells and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere with medium change every 48 hours. To analyze the effects of LH on TRIB expression in GC, exact amounts of LH (10 ng) were added in separate experiments for different durations (30 min, 3 h, and 6 h), followed by analyses of the target proteins including MAPK3/1, and p-MAPK3/1. Additionally, to assess the effect of FSH, exact amounts of FSH (1 ng) were added in separate experiments at different time points (5 min, 30 min, 3 h, 6 h; n=3), followed by protein analyses. For LH treatments, four independent experiments (n=4) were performed, and three time points were measured while for FSH treatments, three independent experiments (n=3) were performed with four time points measured. Recombinant FSH (catalog #F4021-10UG) and LH (catalog #L6420-10UG) were purchased from Millipore Sigma (Sigma Aldrich), USA.

2.4. Functional Studies

Functional studies have been previously reported for TRIB2 by our laboratory [23, 27, 29]. We used the same approach of CRISPR/Cas9 in the current study to investigate the function of TRIB3 in GC of ovarian follicles.

The CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used through the guide-it CRISPR/Cas9 system (Takara Bio) for the cloning and expression of target single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for TRIB3 inhibition in GC. Two sgRNAs were designed and their efficiency was tested before transfection experiments using the Guide-it sgRNA in vitro transcription and Screening System (Takara Bio), as previously reported [23, 27]. GC were collected from slaughterhouse ovaries and cultured in 12-well plates at a density of 0.1×106 cells in McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented as described above (n=4 independent experiments with duplicate wells for each treatment). Nanoparticle complexes from the Xfect transfection kit (Takara Bio) were applied to GC, 24 h after cells were seeded, and incubated for 9h at 37°C then removed and replaced with complete growth medium. Transfected GC, along with control GC (transfection with an empty vector or no transfection control), remained in culture under the same conditions for 48h. Cells were collected for protein extraction to perform Western blot analyses. The effects of TRIB3 inhibition on MAPK and Akt pathways were verified by analyzing phosphorylation levels of MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2), p38MAPK (MAPK14) and Akt.

2.5. Protein Extraction And Western Blot Analyses

Granulosa cells from in vitro experiments were collected and homogenized in M-PER buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Sigma Aldrich), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 1 minute at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined from the recovered supernatant using the BCA Protein Assay Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described by the manufacturer.

For western blot analyses,

in vitro samples (10ug total protein) were resolved by one-dimensional denaturing Novex Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF; Novex Life Technologies, Invitrogen). Antibodies were purchased from New England Biolabs/Cell Signaling Technology, unless otherwise stated. The membranes were incubated with anti-TRIB3 (1:500), anti-TRIB2 (1:500; from our own laboratory [

23]), anti-MAPK3/1 (1:1000; cat.#4695S), anti-p-MAPK3/1 (1:1000; cat.#4370S), anti-MAPK14, (1:1000; cat.#9212S) anti-p-MAPK14 (1:1000; cat.#4511S), anti-AKT (1:1000; cat.#9272S), and anti-p-AKT (1:1000; cat.#4060S) antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Revelation was performed using the SuperSignal West Atto Ultimate Sensitivity Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). following the manufacturer’s protocol. The revelation was carried out using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad). β-actin (ACTB) was used as the reference protein, with anti-β actin antibodies. Primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling and secondary antibody and anti-β actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz.

2.6. RNA Preparation and RT-qPCR Analysis

For in vivo samples, the expression and regulation of TRIB1, TRIB2, and TRIB3 mRNA were assessed by RT-qPCR during follicular development and post hCG injection using the following specific primers: for TRIB1 (accession# NM_001101105), forward: gttctgcattcctgaccacat and reverse: tgtacccaggttccaagacag; amplicon size (140bp); for TRIB2 (accession# NM_178317), forward: ttgggtatttctgtccctga and reverse: acgtgtcacctacccaaaaa; amplicon size (237bp); for TRIB3 (accession# NM_001076103), forward: actaccccttccaggactcag and reserve: ttctccttcctcctctgcttc; amplicon size (278bp). An annealing temperature of 59°C was used for all three sets of primers. Total RNA was extracted from bovine granulosa cells (GC) obtained from follicles at various developmental stages (day 5 dominant follicles, DF and ovulatory follicles, OF), as well as from follicular wall (FW), which include granulosa cells and theca cells (TC) at different time points (0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours) post-hCG injection. Samples of FW collected from day 7 dominant follicles are referred to as 0 h samples. Also, separate TC samples from DF and OF were analyzed for TRIB members expression as compared to GC samples.

Total RNA was extracted from

in vivo samples using the TRIzol Plus RNA purification kit (Invitrogen) and quantified by absorbance at 260nm. Reverse transcription was performed (with 1μg of total RNA from different samples) using the SMART (Switching Mechanism At 5’-end of RNA Transcript) PCR cDNA synthesis technology (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s procedure.

RPL19 was used as reference gene.

CYP17A1 and

CYP19A1 were used as markers for TC and GC, respectively. RT-qPCR experiments were performed using the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s procedure with the following conditions: . RT-qPCR data were analyzed using the Livak method (2

-ΔΔCq) [

30], and RPL19 was used as reference gene [

31].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM derived from three or more independent experiments, as specified within the text. To compare different samples or treatments from in vivo experiments, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess effects of hCG injection. In instances where ANOVA revealed a significant difference (P < 0.05), the Tukey-Kramer test was used for multiple comparisons of individual means among DF and OF and the Dunnett’s test was used for follicular walls samples.

For in vitro experiments, ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer analyses (P < 0.05) were applied to compare various time points post-FSH and LH treatments, with 0 hour serving as the control. Statistical analyses were conducted using PRISM software 9 for macOS (GraphPad). In the case of RT-qPCR data, the results are presented as normalized amounts of respective genes relative to 2-ΔΔCq.

3. Results

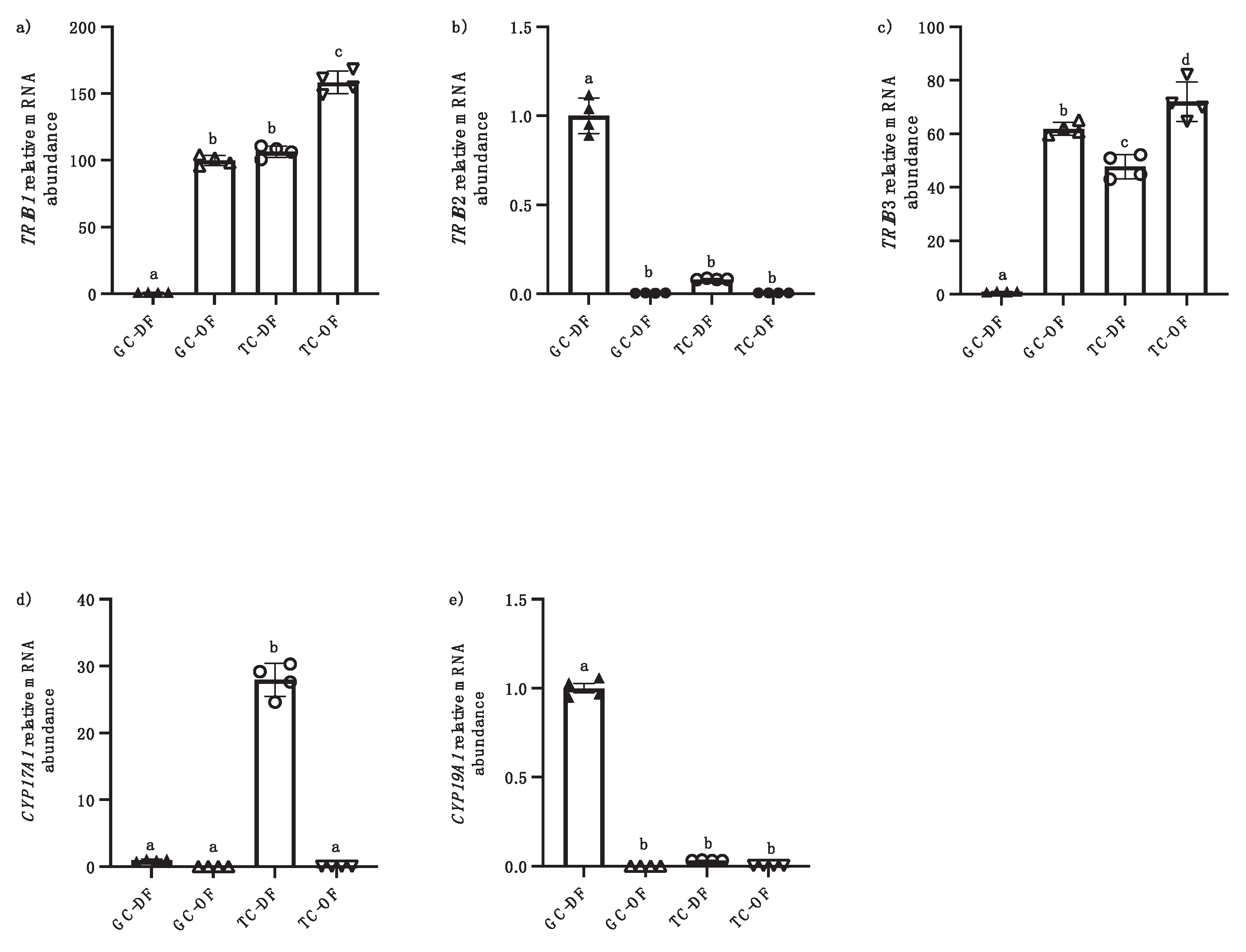

3.1. TRIB Regulation During Follicular Development

We analyzed the expression and regulation of

TRIB1,

TRIB2 and

TRIB3 in an

in vivo model with samples of granulosa cells (GC) and theca cells (TC) from follicles at different developmental stages of dominant (DF) and ovulatory follicles (OF). RT-qPCR results revealed

TRIB members expression in these different reproductive cell populations, namely GC vs. TC.

TRIB2 was predominantly present in GC of dominant follicles (DF) (

Figure 1b; P <0.05), significantly downregulated by hCG in ovulatory follicles (OF) whether in GC or TC and absent in TC of DF as compared to GC of DF (1b, p<0.001). Although

TRIB2 expression was weak in TC, it was stronger in TC from DF than in TC from OF confirming

TRIB2 downregulation by hCG. These results suggest that TC contribution to

TRIB2 expression in the ovary is absent or very limited as compared to GC. In contrast, both

TRIB1 and

TRIB3 were expressed in TC, both from DF and OF (Fig. 1a and 1c).

TRIB1 and

TRIB3 mRNA expression were strongest in OF post-hCG both in GC and TC as compared to DF (a and c, p<0.05). Interestingly,

TRIB1 and

TRIB3 were expressed in GC only in OF post-hCG as compared to GC of DF (

Figure 1a and c; P < 0.0001).

CYP19A1 was utilized as a marker for GC and

CYP17A1 as a marker for TC. As expected,

CYP17A1 was present in TC and absent in GC from day 5 DF (Fig. 1d, p<0.0001). Conversely,

CYP19A1 was significantly expressed in GC and not observed in TC (Fig. 1e, p<0.0001).

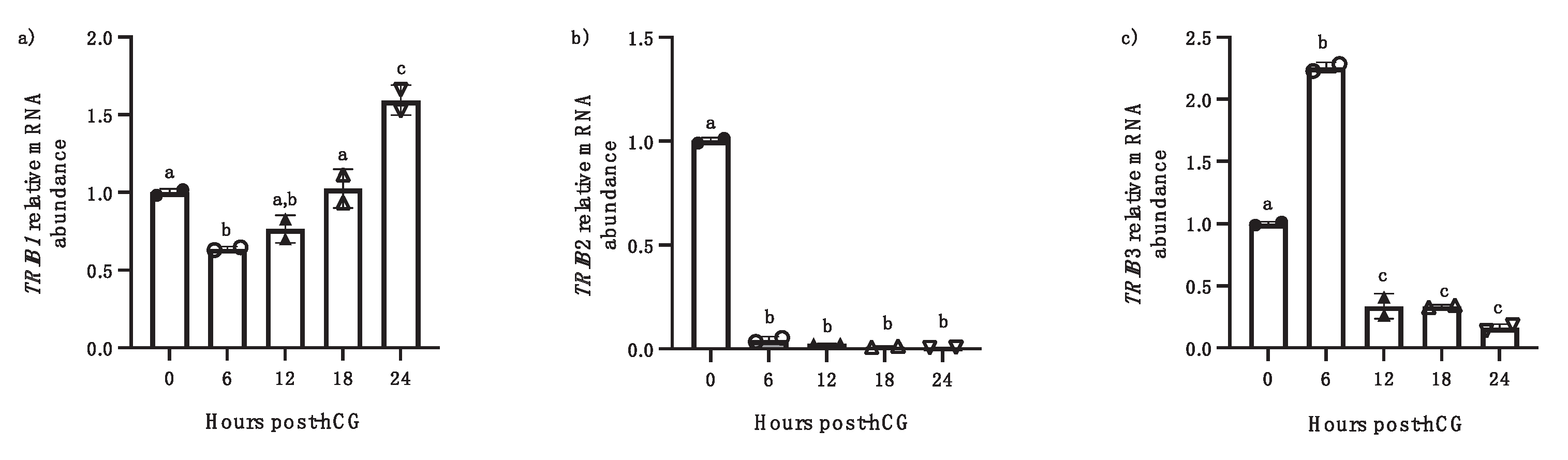

3.2. Regulation of TRIBs by hCG During Follicular Development

Further, we analyzed the expression and regulation of TRIB members in follicular wall samples (FW), containing both granulosa cells and theca cells, at different times post-hCG injection (6h, 12h, 18, 24h). Analysis of the temporal expression of TRIB1 and TRIB3 at the different time points post-hCG injection revealed a different pattern of significant increase in mRNA amounts. TRIB1 mRNA expression in FW exhibited an early decrease at 6 h post-hCG and then showed an increase and significant upregulation at 24 h post-hCG injection compared to 0 h (Fig. 2a; p<0.001). However, TRIB3 expression showed a significant upregulation in FW only at 6 h post-hCG (Fig. 3B; p<0.05) before a drastic decrease from 12h through 24 h post-hCG (p<0.001). TRIB2 expression was significantly downregulated by hCG starting at 6h through 24h post-hCG (b, p<0.0001)

Figure 2.

TRIB1, TRIB2 and TRIB3 mRNA regulation was analyzed in follicular walls (containing granulosa and theca cells) isolated from OF at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h (h) post-hCG injection. TRIB1 mRNA was significantly increased in FW at 24 h post-hCG as compared to 0h (a, p<0.05). TRIB2 was significantly downregulated starting at 6h through 24h post-hCG (b, p<0.0001). TRIB3 mRNA was significantly increased in FW at 6 h post-hCG as compared to 0h and then was reduced at 12h through 24h post-hCG injection (p < 0.001). Different letters denote samples that differ significantly. (ANOVA, Dunnett test).

Figure 2.

TRIB1, TRIB2 and TRIB3 mRNA regulation was analyzed in follicular walls (containing granulosa and theca cells) isolated from OF at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h (h) post-hCG injection. TRIB1 mRNA was significantly increased in FW at 24 h post-hCG as compared to 0h (a, p<0.05). TRIB2 was significantly downregulated starting at 6h through 24h post-hCG (b, p<0.0001). TRIB3 mRNA was significantly increased in FW at 6 h post-hCG as compared to 0h and then was reduced at 12h through 24h post-hCG injection (p < 0.001). Different letters denote samples that differ significantly. (ANOVA, Dunnett test).

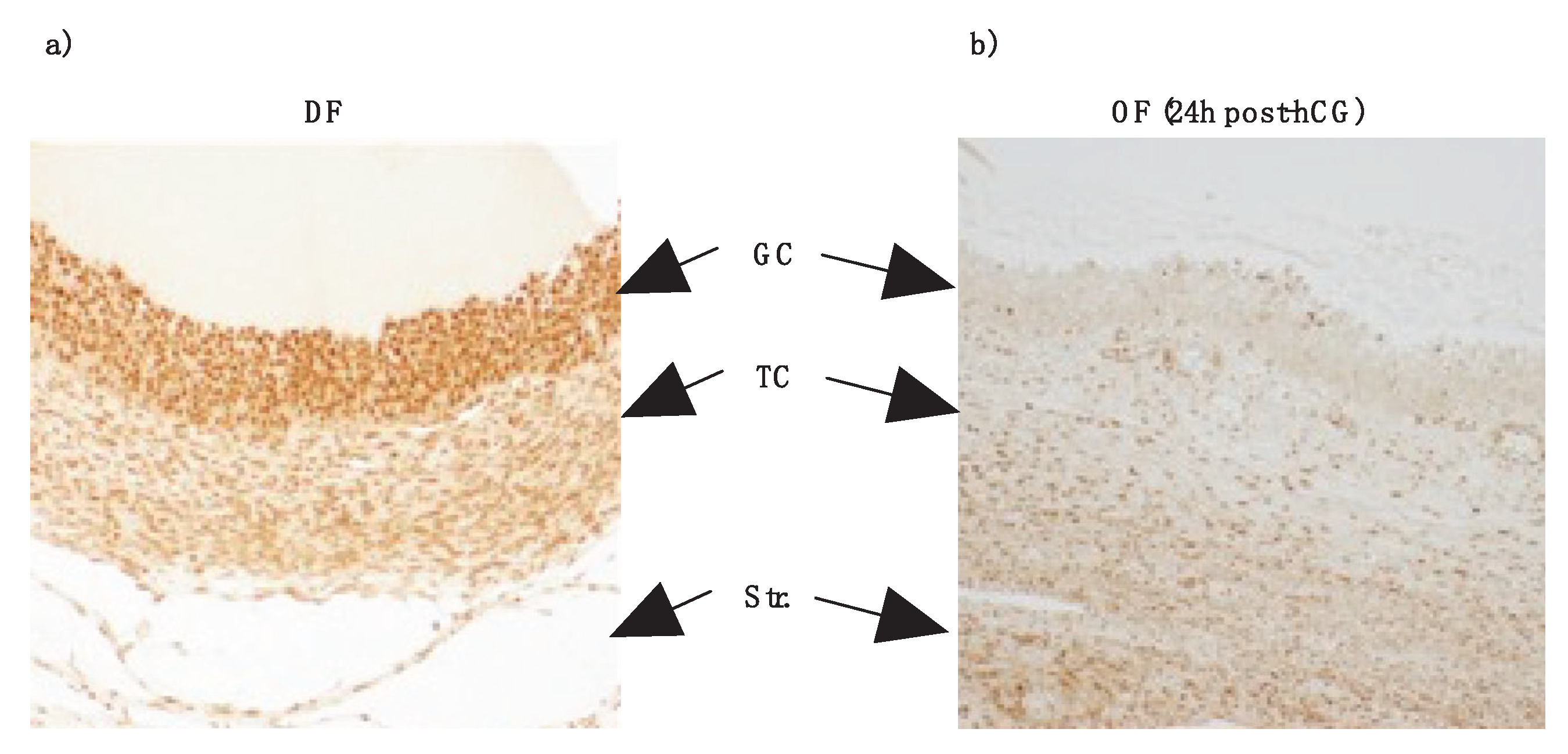

3.3. TRIB2 Downregulation by hcg Confirmed via Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Results from IHC, using in-house anti-TRIB2 antibodies previously described [

23], confirmed the presence of TRIB2 in the GC layer of DF as compared to the TC layer and also confirmed downregulation of TRIB2 in OF post-hCG injection. GC from day 5 dominant follicles (DF; Fig. 3a) exhibited a stronger labeling signal as compared to theca cells of the same follicle and to GC from ovulatory follicles (OF) 24 h following hCG injection (Fig. 3b). Theca cells also were stained, albeit weaker than in GC (

Figure 3a and b). These findings were consistent with TRIB2 mRNA and protein expression patterns observed in DF and OF, as determined in this study and previously reported [

23]. In contrast to

TRIB2, our data show that

TRIB1 and

TRIB3 are induced by hCG and we suspect they might play significant roles in the ovulation process or the formation and function of the corpus luteum (CL).

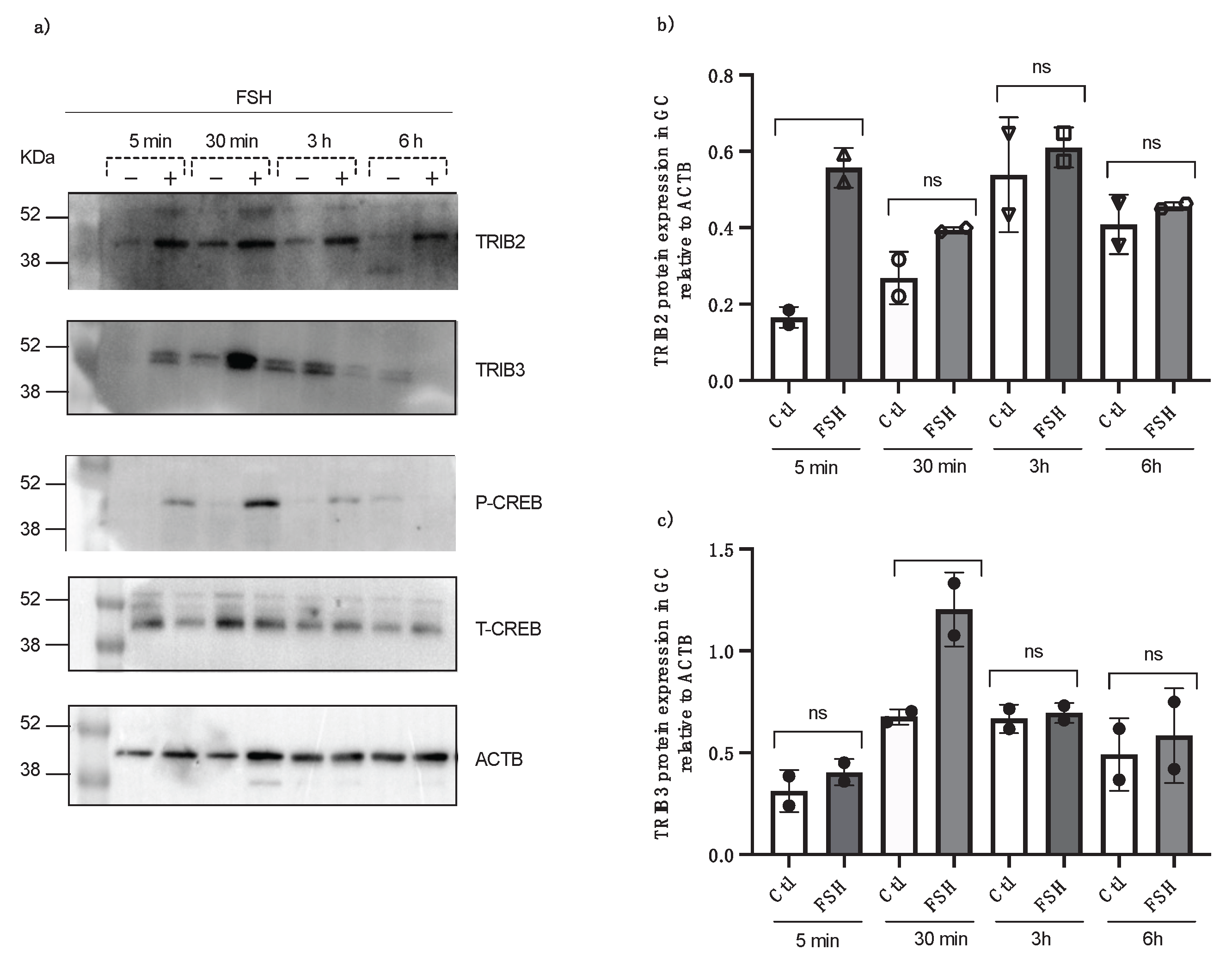

3.4. TRIBs Regulation by FSH In Vitro

Cultured granulosa cells were treated with FSH in a serum-free medium and collected at 5 minutes, 30 minutes, 3 hours, and 6 hours following FSH treatment and TRIB2 and TRIB3 protein expression were analyzed by Western blot using specific anti-TRIB2 and anti-TRIB3 antibodies. Data revealed a significant induction of TRIB2 expression by FSH at 5 minutes post-incubation (Fig. 4a and b; p<0.01) while a significant expression of TRIB3 was obtained at 30 minutes post-FSH treatment (Fig. 4a and c; p<0.05). Additionally, phospho and total CREB antibodies (Cell Signaling) were tested to confirm granulosa cells response to FSH treatments, and the results showed that starting at 5 min through 30 min post-FSH treatment, there was significantly more expression of p-CREB (Fig. 4a) as compared to control.

Figure 4.

TRIB2 and TRIB3 protein expression in bovine GC post FSH treatment from in vitro samples at different times (5 min, 30 min, 3 h and 6h). Total protein extracts of GC were analyzed by western blot using anti-TRIB2 and anti-TRIB3 antibodies. TRIB2 and TRIB3 are induced by FSH at different times. The strongest TRIB2 protein expression was observed in the GC, 5 min post FSH treatment, while TRIB3 was expressed significantly in GC, 30 min post FSH treatments. Anti-p-CREB and anti-t-CREB were used to confirm GC response to FSH treatment (*p<0.05; **p<0.001).

Figure 4.

TRIB2 and TRIB3 protein expression in bovine GC post FSH treatment from in vitro samples at different times (5 min, 30 min, 3 h and 6h). Total protein extracts of GC were analyzed by western blot using anti-TRIB2 and anti-TRIB3 antibodies. TRIB2 and TRIB3 are induced by FSH at different times. The strongest TRIB2 protein expression was observed in the GC, 5 min post FSH treatment, while TRIB3 was expressed significantly in GC, 30 min post FSH treatments. Anti-p-CREB and anti-t-CREB were used to confirm GC response to FSH treatment (*p<0.05; **p<0.001).

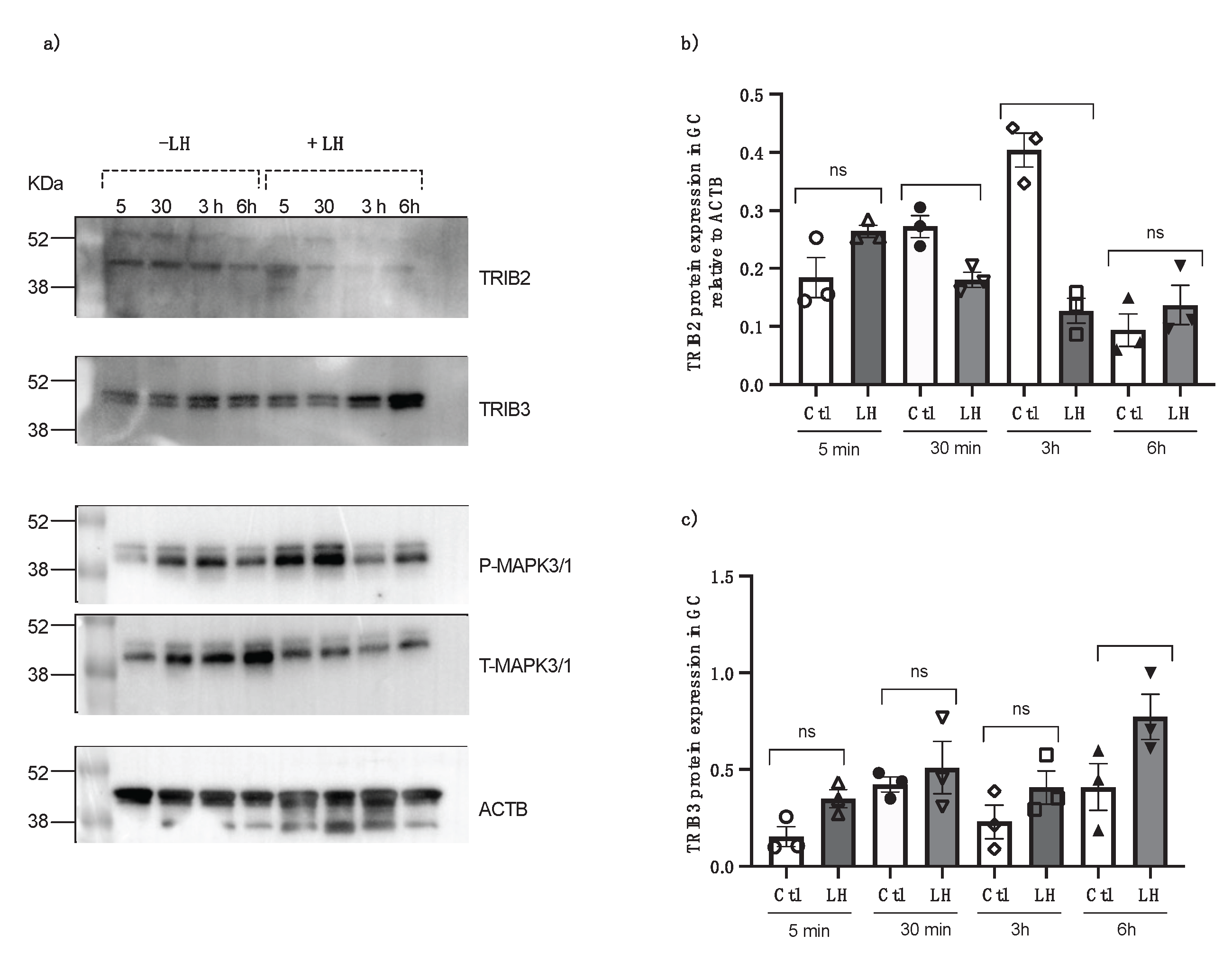

3.5. TRIBs Regulation by LH In Vitro

To verify the effects of LH on TRIBs expression, granulosa cells were cultured in a medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and treated with LH. Cells were collected at 5 minutes, 30 minutes, 3 hours, and 6 hours post-LH treatment. Control cells were collected at the same times. The data revealed that LH suppresses TRIB2 expression, particularly at 3 hours post-LH treatment (Fig. 5a and b; p<0.001). In contrast, TRIB3 expression is induced by LH, especially at 6 hours following LH treatment (Fig. 5a and c; p<0.05). Granulosa cells response to LH treatment was confirmed using total and phospho MAP kinase 3/1 (ERK 1/2). The results showed that there is more protein expression of p-MAPK3/1 at 5 minutes and 30 minutes post LH treatment (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

TRIB2 and TRIB3 protein expression in bovine GC following treatment with LH at different times (5 min, 30 min, 3 h and 6h) from in vitro samples. Western blot analyses of TRIB2 and TRIB3 show LH suppresses TRIB2 expression at 3h post-LH, whereas TRIB3 expression is induced by LH, particularly at 6-hour post-LH compared to the control. Anti-t-MAPK3/1 and anti-p-MAPK3/1 were used to confirm GC response to LH treatment (*p<0.05; ***p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

TRIB2 and TRIB3 protein expression in bovine GC following treatment with LH at different times (5 min, 30 min, 3 h and 6h) from in vitro samples. Western blot analyses of TRIB2 and TRIB3 show LH suppresses TRIB2 expression at 3h post-LH, whereas TRIB3 expression is induced by LH, particularly at 6-hour post-LH compared to the control. Anti-t-MAPK3/1 and anti-p-MAPK3/1 were used to confirm GC response to LH treatment (*p<0.05; ***p<0.0001).

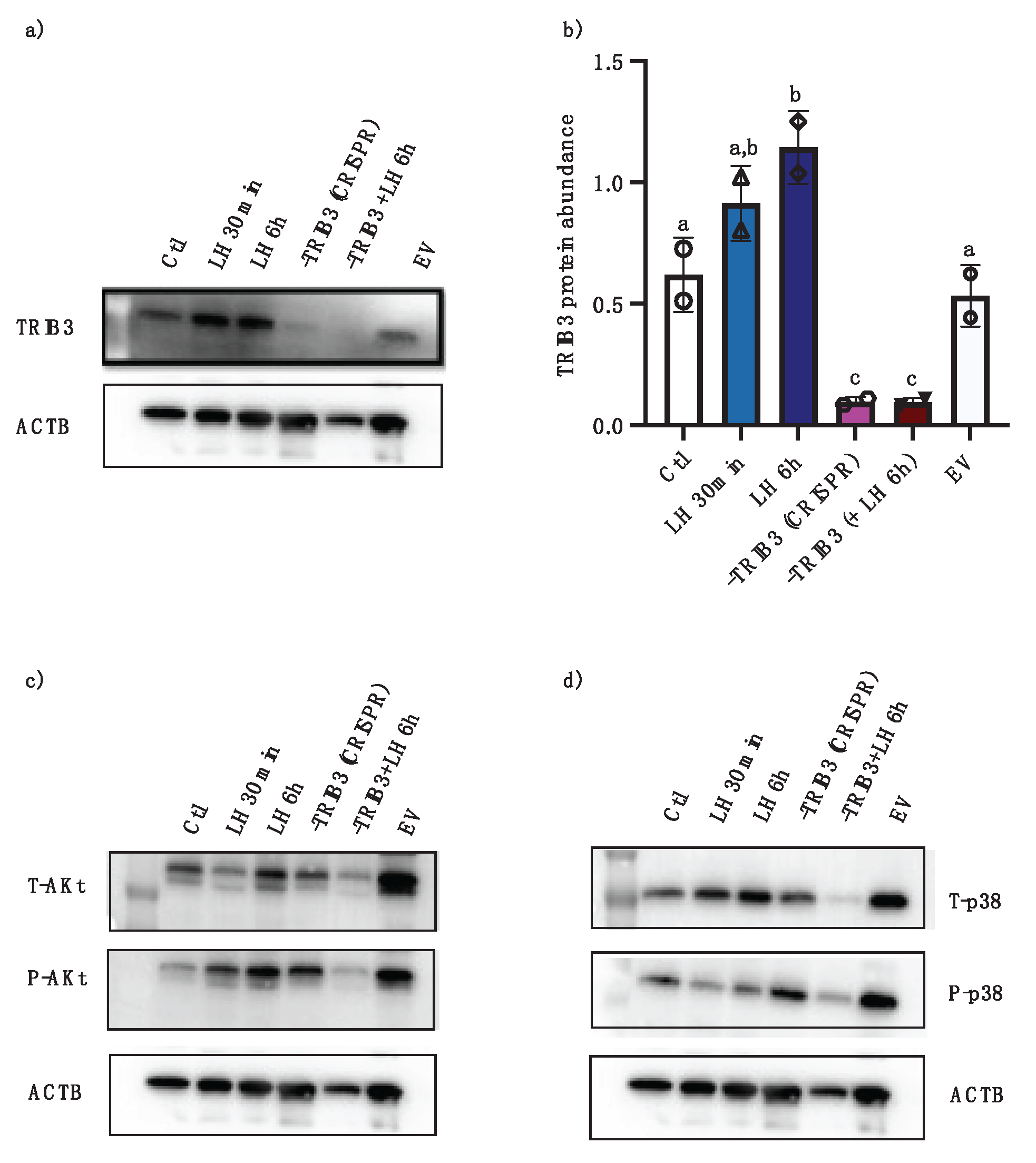

3.6. Functional Studies

Two sgRNA sequences were synthesized and tested for TRIB3 knock-down using the CRISPR/Cas9 approach in granulosa cells. A sgRNA with 96.1% efficiency at directing Cas9-mediated cleavage of TRIB3 was identified and utilized for cloning into the pGuide-it vectors for plasmid construct and subsequent transfection of GC. Western blot analyses confirmed TRIB3 inhibition in GC via CRISPR/Cas9 as compared to control and empty vector (Fig. 6a and b; p<0.001). The effects of TRIB 3 inhibition were assessed by analyzing potential TRIB3 targets Akt and p38 using anti-pAKT, tAKt , pP38, and tP38 antibodies in Western blots. Results provide evidence that there is less pAKt in TRIB3-inhibited GC (Fig. 6c), whereas there were increased amounts of p-P38 in TRIB3-inhibited cells (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that that TRIB3 inhibition via CRISPR-Cas9 might have positive effect on AKt signaling pathway in GC but might negative effect on P38 signaling pathway in GC.

The results of TRIB3 inhibition via CRISPR-Cas9 suggested that TRIB3 might have positive effect on AKt signaling pathway in GC, while negatively affecting P38 signaling pathway in GC. Our current data provide evidence that TRIB2 could be involved in granulosa cells proliferation and follicular development while TRIB1 and TRIB3 could be involved in the ovulation and luteinization processes, respectively.

Figure 6.

Effects of TRIB3 inhibition via CRISPR/Cas9 on Akt and p38MAPK. Western blot analyses confirmed TRIB3 expression inhibition via CRISPR/Cas9 as compared to control and empty vector (a and b, p<0.05). LH treatment induced TRIB expression at 6h in the absence of CRISPR/Cas9 while LH treatment following CRISPR/Cas9 did not increase TRIB3 abundance (a and b, p<0.05). Western blot analyses of AKt show a reduction in p-AKT in TRIB3 KO samples (c) while p38MAPK phosphorylation seem to increase in TRIB3 KO samples (d).

Figure 6.

Effects of TRIB3 inhibition via CRISPR/Cas9 on Akt and p38MAPK. Western blot analyses confirmed TRIB3 expression inhibition via CRISPR/Cas9 as compared to control and empty vector (a and b, p<0.05). LH treatment induced TRIB expression at 6h in the absence of CRISPR/Cas9 while LH treatment following CRISPR/Cas9 did not increase TRIB3 abundance (a and b, p<0.05). Western blot analyses of AKt show a reduction in p-AKT in TRIB3 KO samples (c) while p38MAPK phosphorylation seem to increase in TRIB3 KO samples (d).

4. Discussion

It has been demonstrated that the expression of TRIB pseudokinases exhibits specificity to different tissues and cell types [

32]. In our previous study, we elucidated the regulation of TRIB expression in granulosa cells (GC) within ovarian follicles throughout follicular development, particularly TRIB2 [

23]. Furthermore, previously published findings offer compelling evidence indicating that TRIB2 serves as a regulator of GC proliferation and has the potential to influence steroidogenesis and MAPK signaling pathways within these reproductive cells [

23]. Our current data confirms that TRIB2 could be involved in granulosa cells proliferation and follicular development and provide evidence that TRIB1 and TRIB3 could be involved in the ovulation and luteinization processes, respectively. Taken together, these findings suggest that TRIB2 may play a pivotal role in modulating GC proliferation and follicular growth during the crucial phases preceding ovulation in the final stages of follicular development.

We showed that, contrary to TRIB2,

TRIB1 expression was induced in ovulatory follicles following hCG injection in accordance with previously reported data in bovine and other species [

33]. This expression pattern suggests that

TRIB1 may be involved in granulosa and cumulus cells function during oocyte maturation. Similarly, our data also showed that TRIB3 expression was induced by hCG/LH although at different times as compared to

TRIB1. We previously reported that

TRIB3 expression was strongest in the corpus luteum as compared to all stages of follicular development [

23] suggesting a role for TRIB3 in GC differentiation into luteal cells or in the function of the corpus luteum. TRIB1 as well as TRIB3 were also shown to be upregulated during the ovulatory period in cumulus cells, whereas TRIB2 was downregulated during the same period [

22]. We have shown in the current study that TRIB2 expression was downregulated in bovine GC from hCG-induced OF in accordance with previous studies [22, 34, 35]. The differences in regulation of Tribbles members expression in GC as well as in the theca layer during follicular development indicate that they may have different roles either in the final follicular growth, the ovulation process, corpus luteum formation and function or steroidogenesis. Observations at the protein level support the hypothesis that TRIB2 as well as TRIB3 are hormonally regulated by FSH and LH suggesting that these hormones may control differently TRIB2 and TRIB3 ability to affect target genes function and ovarian function.

TRIB3 is involved in several crucial cellular processes, including stress responses, proliferation, adipose tissue homeostasis, metabolic regulation, and cellular signaling pathways [36, 37]. Recent research highlights its significant role in female reproduction, particularly in ovarian function and follicular development [

38]. TRIB3 is known to interact with various signaling pathways, including the AKt and MAPK pathways, which are vital for cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation [37, 39, 40]. By modulating these pathways, TRIB3 can affect granulosa cell function and, consequently, follicular development and oocyte quality in human [

40]. In this research we have shown that

TRIB3 is expressed in TC, both from dominant follicles and ovulatory follicles. This observation combined with previously reported data showing TRIB3 strongest expression in the corpus luteum [

22] suggest an important role for TRIB3 in granulosa and theca cells differentiation and steroidogenesis.

The results of TRIB3 inhibition via CRISPR-Cas9 suggested that TRIB3 might have positive effect on AKt signaling pathway in GC, while negatively affecting P38MAPK signaling pathway in GC in bovine species. During follicle development, FSH promotes the proliferation and steroidogenesis of GC by binding to its receptor (FSHR) on the GC membrane. Reduced expression of FSHR typically leads to a diminished response of GC to FSH stimulation [

41]. In the current study, our results showed that TRIB2 and TRIB3 are induced by FSH at different times. TRIB3 regulatory effect on FSH signaling pathways can impact the growth and selection of dominant follicles, thus influencing ovulation and fertility. Moreover, TRIBs might play a role in the response to the luteinizing hormone (LH), which triggers ovulation [

23]. Our current data shows that LH suppresses TRIB2 expression, particularly at 3 hours post-LH treatment. On the other hand, TRIB3 expression is induced by LH, especially at 6 hours following LH treatment. By modulating the pathways activated by LH, TRIBs may affect the final stages of oocyte maturation and the subsequent release of the oocyte from the follicle. This highlights the importance of TRIBs in coordinating the hormonal signals that are essential for successful ovulation.

We previously showed a likely correlation between TRIB2 and MAPK signaling in GC since lack of TRIB2 resulted in decreased phosphorylation of p38MAPK and MAPK3/1 supporting the idea that TRIB2 could function to control GC proliferation through MAPK modulation and could control an efficient activation of p38MAPK. Similarly, our current study showed that TRIB3 tends to negatively modulate p38MAPK. Since members of p38MAPK family act in a cell environment- and cell type-specific manner to mediate various biological signals leading to proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration, it is likely that the regulation of different TRIB members relative to their key partners in granulosa cells will dictate the effects in follicular development, ovulation or corpus luteum function.

Overall, the current findings confirm previously reported data regarding TRIB members relation in bovine granulosa cells and provide further evidence for their roles and relevance in the ovary and the activity of granulosa cells.

Author Contributions

Investigations, M.P. and K.N.; Visualization, M.P. and K.N.; Validation, M.P. and K.N.; Formal analysis, M.P. and K.N.; Writing-Original draft preparation, M.P.; Methodology, M.P. and K.N.; Conceptualization, K.N.; Resources, K.N.; Writing-Review and Editing, M.P. and K.N.; Supervision, K.N.; Project Administration, K.N.; Funding Acquisition, K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (RGPIN#04516) to K. Ndiaye and by an Alliance Grant from NSERC (#RN001413) to K. Ndiaye. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Montreal reviewed and approved all the experimental protocols, as the animals were cared for in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and according to ARRIVE guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jacques G. Lussier for his suggestions and critical comments throughout the progress of this project and for sharing in vivo granulosa and theca cells samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AKT, Protein Kinase B

CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein

CYP17A1, Cytochrome P450, Family 17, Subfamily A, Polypeptide 1

CYP19A1, Cytochrome P450, Family 19, Subfamily A, Polypeptide 1

ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase

FSH, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

GC, Granulosa Cell

hCG, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase

RT-qPCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

TC, theca cells

TRIB, Tribbles pseudokinases

References

- Fortune J, Rivera G, Evans A, Turzillo A. Differentiation of dominant versus subordinate follicles in cattle. Biology of reproduction. 2001;65(3):648-54. [CrossRef]

- Ginther O, Beg MA, Bergfelt D, Donadeu F, Kot K. Follicle selection in monovular species. Biology of reproduction. 2001;65(3):638-47. [CrossRef]

- Richards JS, Ascoli M. Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine signaling pathways that regulate ovulation. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2018;29(5):313-25. [CrossRef]

- Lucy M. The bovine dominant ovarian follicle. Journal of animal science. 2007;85(suppl_13):E89-E99. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye K, Fayad T, Silversides DW, Sirois J, Lussier JG. Identification of downregulated messenger RNAs in bovine granulosa cells of dominant follicles following stimulation with human chorionic gonadotropin. Biology of reproduction. 2005;73(2):324-33. [CrossRef]

- Nimz M, Spitschak M, Fürbass R, Vanselow J. The pre-ovulatory luteinizing hormone surge is followed by down-regulation of CYP19A1, HSD3B1, and CYP17A1 and chromatin condensation of the corresponding promoters in bovine follicles. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010 Dec;77(12):1040-8. PMID: 21069797. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld CS, Wagner JS, Roberts RM, Lubahn DB. Intraovarian actions of oestrogen. Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2001;122(2):215-26. [CrossRef]

- Sayasith K, Bouchard N, Doré M, Sirois J. Regulation of bovine tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 6 in ovarian follicles during the ovulatory process and promoter activation in granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149(12):6213-25. [CrossRef]

- Sayasith K, Sirois J, Lussier JG. Expression, regulation, and promoter activation of vanin-2 (VNN2) in bovine follicles prior to ovulation. Biology of reproduction. 2013;89(4):98, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Lussier JG, Diouf MN, Lévesque V, Sirois J, Ndiaye K. Gene expression profiling of upregulated mRNAs in granulosa cells of bovine ovulatory follicles following stimulation with hCG. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2017;15:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye K, Fayad T, Silversides DW, Sirois J, Lussier JG. Identification of downregulated messenger RNAs in bovine granulosa cells of dominant follicles following stimulation with human chorionic gonadotropin. Biol Reprod. 2005 Aug;73(2):324-33. Epub 2005 Apr 13. PMID: 15829623. [CrossRef]

- Hegedus Z, Czibula A, Kiss-Toth E. Tribbles: a family of kinase-like proteins with potent signalling regulatory function. Cellular signalling. 2007;19(2):238-50. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama T, Nakamura T. Tribbles in disease: Signaling pathways important for cellular function and neoplastic transformation. Cancer science. 2011;102(6):1115-22. [CrossRef]

- Wei S-C, Rosenberg IM, Cao Z, Huett AS, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Tribbles 2 (Trib2) is a novel regulator of toll-like receptor 5 signaling. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18(5):877-88. [CrossRef]

- Dobens Jr LL, Bouyain S. Developmental roles of tribbles protein family members. Developmental Dynamics. 2012;241(8):1239-48.

- Li K, Wang F, Cao W-B, Lv X-X, Hua F, Cui B, et al. TRIB3 promotes APL progression through stabilization of the oncoprotein PML-RARα and inhibition of p53-mediated senescence. Cancer cell. 2017;31(5):697-710. e7. [CrossRef]

- Hua F, Li K, Yu J-J, Hu Z-W. The TRIB3-SQSTM1 interaction mediates metabolic stress-promoted tumorigenesis and progression via suppressing autophagic and proteasomal degradation. Autophagy. 2015;11(10):1929-31. [CrossRef]

- Sakai S, Miyajima C, Uchida C, Itoh Y, Hayashi H, Inoue Y. Tribbles-related protein family members as regulators or substrates of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cancer development. Current cancer drug targets. 2016;16(2):147-56. [CrossRef]

- Rzymski T, Paantjens A, Bod J, Harris A. Multiple pathways are involved in the anoxia response of SKIP3 including HuR-regulated RNA stability, NF-κB and ATF4. Oncogene. 2008;27(33):4532-43. [CrossRef]

- Seher TC, Leptin M. Tribbles, a cell-cycle brake that coordinates proliferation and morphogenesis during Drosophila gastrulation. Current Biology. 2000;10(11):623-9. [CrossRef]

- Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rørth P. Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell. 2000;101(5):511-22. [CrossRef]

- Brisard D, Chesnel F, Elis S, Desmarchais A, Sánchez-Lazo L, Chasles M, et al. Tribbles expression in cumulus cells is related to oocyte maturation and fatty acid metabolism. Journal of ovarian research. 2014;7(1):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Warma A, Ndiaye K. Functional effects of Tribbles homolog 2 in bovine ovarian granulosa cells. Biology of reproduction. 2020;102(6):1177-90. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye K, Castonguay A, Benoit G, Silversides DW, Lussier JG. Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) increases phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) in reproductive cells. The FASEB Journal. 2016;30:644.3-.3. [CrossRef]

- Lussier JG, Diouf MN, Levesque V, Sirois J, Ndiaye K. Gene expression profiling of upregulated mRNAs in granulosa cells of bovine ovulatory follicles following stimulation with hCG. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E. 2017;15(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Filion F, Bouchard N, Goff AK, Lussier JG, Sirois J. Molecular Cloning and Induction of Bovine Prostaglandin E Synthase by Gonadotropins in Ovarian Follicles Prior to Ovulationin Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(36):34323-30. [CrossRef]

- Benoit G, Warma A, Lussier JG, Ndiaye K. Gonadotropin regulation of ankyrin-repeat and SOCS-box protein 9 (ASB9) in ovarian follicles and identification of binding partners. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0212571. [CrossRef]

- Portela VM, Zamberlam G, Gonçalves PB, de Oliveira JF, Price CA. Role of angiotensin II in the periovulatory epidermal growth factor-like cascade in bovine granulosa cells in vitro. Biology of reproduction. 2011;85(6):1167-74. [CrossRef]

- Warma A, Lussier JG, Ndiaye K. Tribbles pseudokinase 2 (Trib2) regulates expression of binding partners in bovine granulosa cells. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(4):1533. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001;25(4):402-8.

- Crookenden M, Walker C, Kuhn-Sherlock B, Murray A, Dukkipati V, Heiser A, et al. Evaluation of endogenous control gene expression in bovine neutrophils by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR using microfluidics gene expression arrays. Journal of Dairy Science. 2017;100(8):6763-71. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Francis S, Crossman D, Kiss-Toth E. Regulation of expression and signalling modulator function of mammalian tribbles is cell-type specific. Immunology letters. 2006;104(1-2):171-7. [CrossRef]

- Charlier C, Montfort J, Chabrol O, Brisard D, Nguyen T, Le Cam A, et al. Oocyte-somatic cells interactions, lessons from evolution. BMC genomics. 2012;13:560. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye K, Fayad T, Silversides DW, Sirois J, Lussier JG. Identification of downregulated messenger RNAs in bovine granulosa cells of dominant follicles following stimulation with human chorionic gonadotropin. Biology of reproduction. 2005;73(2):324-33. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Wang C, Li X, Hu Y, Gou R, Guo Q, et al. Down-regulation of TRIB3 inhibits the progression of ovarian cancer via MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Cancer Cell International. 2020;20:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Quiles M, Martinez Campesino L, Morris I, Ilyas Z, Reynolds S, Soon Tan N, Sobrevals Alcaraz P, Stigter ECA, Varga Á, Varga J, van Es R, Vos H, Wilson HL, Kiss-Toth E, Kalkhoven E. The pseudokinase TRIB3 controls adipocyte lipid homeostasis and proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mol Metab. 2023 Dec;78:101829. Epub 2023 Oct 30. PMID: 38445671; PMCID: PMC10663684. [CrossRef]

- Ye MP, Lu WL, Rao QF, Li MJ, Hong HQ, Yang XY, Liu H, Kong JL, Guan RX, Huang Y, Hu QH, Wu FR. Mitochondrial stress induces hepatic stellate cell activation in response to the ATF4/TRIB3 pathway stimulation. J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul;58(7):668-681. Epub 2023 May 7. PMID: 37150773. [CrossRef]

- Bao XY, Sun M, Peng TT, Han DM. TRIB3 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of retinoblastoma cells by activating the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2021;31(4):307-315. PMID: 33896816. [CrossRef]

- Qu J, Liu B, Li B, Du G, Li Y, Wang J, He L, Wan X. TRIB3 suppresses proliferation and invasion and promotes apoptosis of endometrial cancer cells by regulating the AKT signaling pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2019 Mar 27;12:2235-2245. PMID: 30988628; PMCID: PMC6441550. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Si C, Xia L, Wu X, Zhao S, Xu H, et al. TRIB3 regulates FSHR expression in human granulosa cells under high levels of free fatty acids. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2021;19:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Recchia K, Jorge AS, Pessôa LVdF, Botigelli RC, Zugaib VC, de Souza AF, et al. Actions and roles of FSH in germinative cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(18):10110. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).