1. Introduction

Music making and listening to music is generally found to have a positive impact on wellbeing [

1], e.g. reduced stress response [

2,

3,

4] and pain perception [

2,

5] as well as positive effect on immune response [

3,

4,

6,

7], brain plasticity [

1,

8,

9,

10], neurorehabilitation [

11,

12] and healthy ageing [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, in professional musicians, much like in sport athletes, the high physical and mental demands of professionally mastering a musical instrument and performing in the industry have been linked to stresses and illnesses specific to musicians' professions. What has long been a matter of debate for athletes under the names of sports physiology, sports psychology and sports medicine has now been developed as a separate specialist field for the needs of professional musicians under the name “music physiology and musicians' medicine”. In the course of the rapid increase in playing and singing demands on professional musicians and the simultaneous increase in competition in a globalized job market, the physiological and psychological conditions of music-making [

17,

18] and the pathophysiological mechanisms in the development of musical illnesses gradually became the subject of research.

The majority of complaints in musicians are Musculo-fascial imbalances and pain syndromes [

19,

20,

21,

22], various psychosomatic stress situations [

23,

24,

25], including excessive music performance anxiety [

23,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] and musicians dystonia [

30]. Typical triggers are usually an imbalance between burden and resilience as well as professional and private stress situations [

17,

18,

23,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In line with the vulnerability-stress model [

37,

38] both musculoskeletal disorders and musician’s dystonia have been linked with psychological factors such as perfectionism [

39,

40,

41,

42], anxiety [

41,

43,

44] and psychosocial stress [

18,

45,

46] as well as traumatic childhood experiences [

33,

39]. Research consistently shows that musicians experience higher rates of mental health issues compared to the general population. Kenny et al. [

23] found high symptom prevalence rates of affective disorders among Australian professional orchestra musicians, including social phobia (33%), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (22%), and depression (32%). Research by Vaag, Bjørngaard, and Bjerkeset found prevalence rates of 20.1% for symptoms of depression and 14.7% for symptoms of anxiety [

47], increased use of psychotherapy and psychotropic medication [

48] and higher prevalence of impaired sleep [

49] among Norwegian professional musicians. Especially solo or lead artists and internationally touring musicians consistently show highest risks for mental health issues [

31,

50].

Regarding music performance anxiety (MPA), a study by Spahn et al. [

27] found three subgroups of musicians, that are distinguished from each other by symptom severity and the availability of self-efficacy and functional coping strategies. While half of the sample exhibited only few symptoms of MPA (Type I MPA, common “Lampenfieber” [

27]), approximately one quarter showed high symptoms at the beginning of the performance (Type II MPA, [

27]) versus increasing symptoms during performance (Type III MPA, [

27]). The latter group exhibited the lowest values of self-efficacy and adaptive coping and the lowest self-assessment of musical quality[

27]. Given this relationship of increased symptom severity with maladaptive coping [

27] we can hypothesize that these individuals tend to overfocus on or get triggered by errors and/or physical symptoms during performance and are automatically trapped in negative inner self-talk, that leads to a vicious circle of increased symptoms and degraded performance. This may especially happen on stage but is also common during musical lessons or in musical interactions such as chamber music, e.g. as a reaction to critics or merely by the aspect of being observed (“judged”) by others (so called “triggers”).

Schema-focused therapy (SFT), also known as schema therapy, with its focus on early maladaptive schemas, appears particularly well-suited to address these challenges. To provide context for readers unfamiliar with the theoretical framework, we first introduce schema therapy. Schema therapy is an integrative psychological treatment approach developed by Jeffrey Young [

51]. It aims to help individuals understand and change long-standing, deeply ingrained negative patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that originated in childhood and continue to cause problems in adult life. These patterns, known as early maladaptive schemas, are essentially core beliefs or emotional themes that act as a lens through which individuals view themselves, others, and the world. When these schemas are triggered by current life events, they can lead to intense emotional reactions and unhelpful coping strategies. Schema therapy is particularly well-suited to address complex psychological challenges because it combines elements from cognitive-behavioral therapy, attachment theory, psychodynamic concepts, and Gestalt therapy.. At its core, schema therapy focuses on identifying and modifying early maladaptive schemas (EMS), which are self-defeating emotional and cognitive patterns that begin early in development and repeat throughout life. Young [

51] identified 18 early maladaptive schemas that are grouped into five broad domains based on unmet emotional needs in childhood: Disconnection and Rejection, Impaired Autonomy and Performance, Impaired Limits, Other-Directedness and Over-Vigilance and Inhibition. Beyond schemas, schema therapy also utilizes the concept of schema modes,, which are moment-to-moment emotional and cognitive states and coping strategies [

51,

52]. These modes are like different 'parts' of ourselves that are activated in response to specific situations, often triggered by emotional events related to our personal schemas. . Individuals can rapidly shift between these modes [

51,

52]. Young [

51] described four main types of schema modes (see

Table 1 for an overview and detailed description):

- (1)

Child modes: Represent innate, universal emotional states from childhood (e.g., vulnerable child, angry child, impulsive child);

- (2)

Maladaptive coping modes: Represent ways of coping with schema activation (e.g., detached protector, compliant surrenderer, self-aggrandizer);

- (3)

Internalized parent modes: Represent internalized voices of parents or other authority figures (e.g., punitive parent, demanding parent);

- (4)

Healthy Adult mode: Represents the integrated, functional aspect of the self, capable of nurturing, setting limits, and problem-solving.

To illustrate these dynamic internal states, consider a music student receiving critical feedback from a teacher. If this feedback triggers an underlying

Defectiveness/Shame schema, the student might initially experience a

Vulnerable Child mode, feeling deeply hurt, inadequate, and believing, ‘I am fundamentally flawed and exposed.’ This intense emotional pain can then immediately activate various coping responses. One common reaction is a

Detached Protector mode, leading them to emotionally disconnect and appear indifferent to the feedback as a defense. Alternatively, they might shift into an

overcompensating mode, such as

Self-Aggrandizer, where they might dismiss the criticism, become defensive, or even subtly undermine the teacher’s authority to protect their fragile self-esteem. Simultaneously, an internal

Punitive Parent mode might emerge, with self-critical thoughts like, ‘You are a complete failure; this proves you don’t belong here,’ intensifying the shame. This complex interplay of modes is further influenced by the

way criticism is delivered; harsh or shaming feedback from the teacher can exacerbate the student's Vulnerable Child and Punitive Parent modes, while constructive and supportive criticism might facilitate a shift towards a more adaptive response. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the teacher's own schemas (e.g.,

Unrelenting Standards schema) can unconsciously shape their critical approach, adding another layer to the interaction. This highlights how various schema modes often co-activate, creating a complex internal landscape and influencing behavioral responses in challenging situations. In contrast, a student operating from a balanced Healthy Adult mode would be able to process the feedback constructively, acknowledge areas for improvement without self-condemnation, and engage in adaptive problem-solving (example created after [

53]).

Schema-modes are a useful concept to describe the emotional, cognitive and behavioral issues of a client or patient. Schema-focused therapy (and coaching [

54,

55]) is targeted towards the balancing of schema-modes towards healthy strategies and the development of alternative coping strategies for dealing with emotional triggers.

Research on schemata and schema-focused-therapy has led to the development of various questionnaires to assess 1) early maladaptive schemas [

56,

57,

58,

59] and 2) schema-modes [

60,

61,

62]. Most of the available studies assessed mode presence in samples with personality disorders [

63,

64,

65,

66]. A systematic review by [

67] found medium-to-large effect sizes for schema therapy interventions, particularly for personality disorders. Randomized trials comparing schema therapy for personality disorder to psychodynamic [

68] respectively clarification-oriented therapy [

69] demonstrated significant greater recovery in the schema-therapy group for borderline, anxious, paranoid, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. Furthermore, schema-modes have been investigated in eating disorders [

70], obsessive-compulsive disorders [

71,

72,

73,

74] as well as affective and anxiety disorders [

74,

75,

76,

77].

Table 1.

Schema-Modes according to short SMI. 14 Schema-Modes according to the factor structure of short SMI [

60]. Column “Emotional and Behavioral Response” describes typical feelings, beliefs & behavior associated with the mode and evaluated by the respective test items.

Table 1.

Schema-Modes according to short SMI. 14 Schema-Modes according to the factor structure of short SMI [

60]. Column “Emotional and Behavioral Response” describes typical feelings, beliefs & behavior associated with the mode and evaluated by the respective test items.

| Acronym |

Schema-Mode (short SMI, [60])

|

Emotional & Behavioral Type |

Mode Category |

| VC |

Vulnerable Child |

Sadness, Shame, Fear, feeling fundamentally inadequate & excluded, loneliness |

Maladaptive Child Modes |

| AC |

Angry Child |

Anger e.g. in case of abundance, lack of freedom/independence, Revenge, feeling unfairly treated/cheated |

| EC |

Enraged Child |

Rage, out of control anger with intense impulses to destroy things/hurt other people, threatening other people |

| IC |

Impulsive Child |

Impatience, Lack of Self-Control |

| UC |

Undisciplined Child |

Lack of Self-Control, Dismissing Boundaries & Rules, Procrastination boring tasks |

| HC |

Happy Child Mode |

Curiosity, Happiness, Fun, feeling safe, loved & accepted |

Happy Child Mode |

| CS |

Compliant Surrender |

“Freeze” – Response, People Pleasing, Passivity, avoiding conflict, social chameleon, not expressing own needs, underdog, |

Maladaptive Coping Modes (“Protectors” against unpleasant child modes/emotions and inner critic) |

| DPT |

Detached Protector |

“Flight” – Response; Procrastination, Resignation, Not-Responding/Interacting, Dissociation, emotional numbness, emotionally detached |

| DSS |

Detached Self-Soother |

“Flight” – Response; distracting and addictive Behavior (Social Media, Drugs, Work, Gaming), rumination, daydreaming |

| SA |

Self-Aggrandizer |

“Fight”- Response; seeking attention of others, ambition to always be Nr.1, neglecting other people’s feelings and needs, need to control other people |

| BA |

Bully & Attack |

“Fight”- Response; dominant behavior, belittling & bullying others |

| PP |

Punishing Parent |

Denying oneself pleasures, self-harming behavior, feeling of being a bad person, angry at oneself |

Maladaptive Inner Critic |

| DP |

Demanding Parent |

Trying hard to do things “right”, high own standards, sacrificing health and wellbeing, perfectionism, constant self-pressure to achieve |

| HA |

Heathy Adult |

Feeling to be a good person, self-sufficient, self-structured, healthy boundaries (self & others), learning mindset, optimistic, adequate emotional regulation |

Adaptive, Reflected & Flexible Adult Mode |

Research Gap & Hypothesis

To our knowledge, no study so far has investigated the presence and relative expression of schemata and schema-modes in musicians. Schema-focused therapy (SFT), also known as schema therapy, with its focus on early maladaptive schemas and development of personality, as well as its multifaceted approach appears particularly well-suited to address the above-mentioned challenges and vulnerabilities of professional musicians and music students.

The present study investigates schema-modes in music students and its relation to the results of non-clinical, Axis I and Axis II disorders (short SMI [

60], as well as intra-individual degree of coping with the life of a musician (HIL Scale, [

78] ). We choose to investigate schema-modes using short SMI due to the availability of comparison samples in the validation study [

60] and the applicability of results, as schema-therapy and schema-coaching primarily work with modes more than with the underlying schemata. The short SMI [

60], is a widely cited instrument designed to assess schema modes - temporary states of emotions, cognitions, and behaviors associated with underlying schemata. Its particular value lies in providing normative group-level data for healthy controls as well as clinical samples, including Axis I and Axis II patients. While most other studies focus on individual psychiatric disorders, the Short SMI provides data on larger groups of clustered disorders within a single publication. This is especially helpful for our study because, to our knowledge, ours is the first investigation of schema modes or schema-related psychology in musicians. Comparing musicians to a single disorder, or across multiple studies with different methodologies, would be either too specific or too heterogeneous to interpret meaningfully for this target group. Although the Axis I and II classification is based on the older DSM-IV framework - where Axis I refers to clinical disorders such as depression or anxiety, and Axis II to personality disorders - we found this publication suitable due to its large sample sizes and the breadth of clinical groups represented, providing a valuable reference point for interpreting the relative severity and patterns of maladaptive and coping schema modes in our sample.

Given the above presented existing research on MPA, drug use in musicians, and the mediating factors of childhood trauma, perfectionism and anxiety as well as depression in the development of musician’s health problems, we expect heightened scores of vulnerable child modes, self-soothing and overcompensating (perfectionism) coping modes as well as demanding and punishing inner parent modes and reduced healthy adult mode in music students compared to non-clinical controls.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants & Procedure

Music students enrolled in musical performance and/or music pedagogy studies at Zurich University of Arts and Basel Music Academy, including exchange students, were recruited for the online study “Fostering Motivation and Self-Competence”. Advertisement was sent via email distributor and via information given verbally to students enrolled in classes in the field of “music physiology” at the universities. Students were compensated with the optional offer of 1:1 personal feedback on their questionnaire results (20/46 participants signed up for the offer) and a group workshop on healthy coping strategies. The workshop took place at the end of January 2025, two months after completion of data collection.

The instruction was held with positive, resource-oriented wording, hence avoiding clinical sounding terms like “psychological” or “depression”/” anxiety” that might lead to a feeling of stigmatization and a biased sample. Nevertheless, participation was restricted to healthy participants, excluding participants with current (diagnosed) psychological or neurological diseases. This fundamental exclusion criterium was added to the consent form such that participants of the study have given written consent and agreed with the terms of the study, including that they must not take part if they have any psychological or neurological diseases.

On top of that, participants were excluded, who had already completed their primary music education (master degree level), e.g. who were enrolled in a continuous education program or primarily working as music professionals. This exclusion criterium was ensured by adding a respective questions at the beginning of the questionnaire. Study participants, who reported not to be a student any more, where directly routed to the “Thank you” slide at the end of the questionnaire.

In total, N = 46 music students (29 female, 14 male, 3 prefer not to say; mean age = 24.9 years, SD = 4.26, range 18 - 40) of 18 nationalities participated in the study. N = 23 students were enrolled at Zurich University of Arts, N = 15 at Basel Music Academy and N = 7 at other universities or preferred not to say. N = 24 studied music performance (Bachelor, Master), N = 8 music pedagogy and N = 13 various music performance respectively pedagogy subjects (e.g. music for schools, precollege, specialized education or creative music course programs). The sample consisted of 9 pianists, 15 string players, 7 woodwind players, 5 singers and 10 other instruments, that were only present once or participants preferred not to say to ensure anonymity (see section 2.2). Participants indicated medium to high proficiency in English language understanding on a continuous slider scale ranging from 0 (no understanding of English language) - 100 (native speaker) with equally spread values between 52 and 100.

The online survey was setup and conducted via the online platform

https://www.soscisurvey.de and a respective agreement on data processing according to the EU General Data Protection Regulation between Soscisurvey and the University of Zurich as the data controller & collector. The local cantonal ethic committee approved the study request with the BASEC-Nr.: Req-2024-00757.

Further N = 69 individuals have started but not finished the questionnaire. Thirteen participants were directed to the last page due to declining consent, two were excluded due to missing music student status, and 53 participants dropped out during the questionnaire. One additional participant was manually excluded due to missing student status, resulting in a total of 115 valid cases. Additionally, the online survey received a total of N = 646 clicks. Each click corresponds to an access to the questionnaire, regardless of whether the participant closed the survey immediately, read only the introduction, or continued the questionnaire. Multiple accesses by the same participant as well as accesses by search engines were counted as separate clicks. We only consider the 115 valid cases, including dropouts on the consent form and during the questionnaire, because the meaning of clicks is unclear. While the number of clicks is a very rough indicator of reach, it suggests that the survey information reached a relatively broad audience via the channels used. The observed dropout rate in our study was approximately 59 %.

2.2. Questionnaire Material

Socio-demographical questions included question on age, gender, nationality (voluntary), self-estimated fluency in English language. Music-related items encompassed main instrument (voluntary), music school (voluntary), status of musicianship (pre-college, student at music university, teacher, employed, self-employed), past and current study programs (precollege, bachelor, master, continuous education) and musical profile (pedagogy, performance, classical, jazz/rock/pop, school music, theory/composition/sound design). Questions that could lead to the identification of students due to e.g. the small number of students in specific instrumental classes at specific music schools, were kept optional to ensure anonymity. Data analysis was restricted to students currently enrolled in a fundamental university music program (precollege, bachelor, master) in music performance or pedagogy. Other fields of study were assessed to gain a more detailed picture about the participant’s musical background and experience. Additionally, we asked whether the participants had mainly physical, psychological, both or neither complaint related to music making.

2.2.1. Short Schema-Mode-Inventory (Short SMI)

The short Schema-Mode-Inventory (short SMI, [

60]) is a short version of the Schema-Mode-Inventory (SMI, Young et al., 2007) and consists of 118 items compared to 270 items of the original version. The questionnaire has a 14-factor structure (i.e. 14 schema-modes, see

Table 1) with acceptable internal consistencies (Cronbach α’s from .79 to .96) and adequate test-retest reliability. The inventory was developed to gain a shorter questionnaire for the assessment of schema-modes in research and clinical applications and was tested on 319 non-patient controls without psychopathology, 136 patients with Axis I and 236 patients with Axis II disorders (total sample: N = 863, 57.1% female, mean age 34 years,

SD = 11.80, range 18–70). Comparisons with the normative and clinical groups (see Results section) are based on the published summary data reported in the Short SMI validation study, as raw data were not available. Furthermore, the questionnaire showed moderate construct validity compared with several existing scales such as

Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI; Cloninger, Przybeck, Svrakic and Wetzel, 1994),

Irrational Belief Inventory (IBI; Timmerman, Sanderman, Koopmans and Emmelkamp, 1993),

State-Trait Anger Scale (STAS; Spielberger, Jacobs, Russel and Crane, 1983),

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein and Fink, 1998),

Loneliness Scale (LS; de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg, 1999)

, Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ; Griffin and Bartholomew, 1994), Utrecht Coping List (UCL; Schreurs, van de Willige and Brosschot, 1993), Personality Disorder Belief Questionnaire (PDBQ; Dreessen and Arntz, 1995; Narcissism subscale).

2.2.2. Coping with Work as a Musician (HIL-Scale)

The HIL Scale ([

78]) assesses coping with work as a musician through seven items covering the following topics: 1) satisfaction with success at work, (2) confidence in stage situations, (3) satisfaction with breathing while playing, (4) satisfaction with posture while playing, (5) satisfaction with movements while playing, (6) symptoms in the context of music making, and (7) feeling capable of handling one's studies or profession. Responses are recorded on a six-point scale (1 = fully applies to 6 = does not apply at all). After reversing the scores of all items (except for HIL item 6 regarding complaints), high total scores indicate good coping (maximum = 42). The HIL Scale was tested on a sample of 68 musicians and has also been applied to 38 + 105 first-year music students and 29 music teachers. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.84, 0.73, and 0.78, indicating satisfactory reliability. Although no general population norms exist for the HIL, previous studies with music students provide reference values: for example, first-year students (N=105) scored on average 31.7–31.9 (SD ≈ 0.45) across two time points (beginning and end of the academic year), while a similar study on first-year students (N=38; [

78]) reported average scores of 33.33 (SD=4.39) respectively 33.06 (SD=4.62). In another study [

78], music teachers and advanced music students scored lower before an intervention and improved after (teachers: M = 26.8 vs. M=30.0; music students: M = 24.6 vs. M = 28.7). These values suggest that scores around 30 can be interpreted as reflecting moderate to good coping, showing that participants manage the demands of musical performance and study fairly well, though there may still be room for improvement compared to the highest-performing student samples.

2.2.3. Open Questions: Inner Self-Talk

The following optional open response questions were added to the questionnaire to gain a complete understanding of the participants’ constructive and destructive inner self-talk as well as other social, psychological or physical issues:

- (1)

If you have complaints related to making music, what are they?

- (2)

If you have/have had problems with a teacher or orchestra or chamber music partner currently or in the past, what problems were they?

- (3)

What are typical thoughts (positive and negative) you have in musical situations (practice, rehearsal, lesson, stage)?

These questions were not derived from previously established instruments but were developed based on our clinical experience and exchange with other experts in the field of music physiology and psychology. Question 1 reflects a commonly used open question to assess music-related problems in addition to standardized closed questions (e.g., from the HIL scale). Question 2 was included to address frequently reported difficulties in communication or hierarchical settings such as ensembles and orchestras. Question 3 aimed to capture typical patterns of inner self-talk/thoughts, providing insights into both constructive self-guidance and potentially maladaptive patterns that may reflect inner parent modes. We were interested in whether these aspects, which we often encounter in clinical and educational practice, might also be reflected in the schema mode results of the sample. Since no previous research has investigated schema modes in musicians nor developed a respective questionnaire, we decided to include these open, exploratory questions as an initial step.

Free responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using a two-step lexical categorization procedure. First, individual responses were translated into nominalized expressions capturing the core content of each statement. Second, these expressions were grouped into descriptive categories based on similarity of content, and the frequency of each category across participants was counted. Each participant could contribute only once per category per question. No formal coding manual was used; categories were derived directly from the responses and represent the full range of issues mentioned by the sample. This approach is exploratory and descriptive, aiming to provide an overview of typical complaints, self-talk, and social or organizational issues among music students, rather than to perform an interpretive thematic analysis.

2.3. Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were conducted using the open-source statistical software package R (Version 4.50) and the R packages dplyr, tidyr, tidyverse, multcomp, Hmisc, car, effsize, psych, sjstats and stats. Plots were created with the R package ggplot2 and fmsb.

Statistical differences between the scores of our sample and the comparison groups [

60] were analyzed using pairwise t-tests. Shapiro-Wilk-test did not reject the assumption of normality (

p > 0.05 for all comparisons), parametric tests were used for statistical analyses. Pearson Correlations were used to assess the relationship between Short SMI Modes and HIL Scores. K-Means Clustering and Hierarchical Clustering were used to perform a classification of the sample into distinct psychological profiles. Free responses on open-ended questions were analyzed in a two-step lexical approach (see section 2.2.3): 1) Translation of the individual responses in nominalized expressions and 2) categorization of the nominalizations based on content. Finally, the frequency of the occurrence of the categories across the sample was counted for each question .

3. Results

3.1. Schema-Modes (SMI) in Music Students

Scores on short SMI (Schema-Mode-Inventory SMI, [60)) were compared with the three samples in the validation study of the questionnaire [

60]: Non-patient controls, Axis I patients and Axis II patients (see

Table 2). These comparisons were based on the published summary data reported in the validation study, as raw data were not available. The validation study reports clinical groups classified according to Axis I (clinical disorders such as depression or anxiety) and Axis II (personality disorders) categories from the DSM-IV framework. While these classifications are now outdated in DSM-5/ICD-11, we used them here because the Short SMI data provide large, clustered clinical samples that serve as a practical reference point for interpreting the relative severity and patterns of maladaptive and coping schema modes in our music student sample.

Effect sizes were calculated relative to the published summary statistics of the Short SMI validation study. While this allows descriptive comparisons between the music student sample and the normative and clinical groups, the absence of raw data limits the ability to conduct formal statistical tests or check distributional assumptions in the reference samples. In summary, the participants of the present study significantly differ in most of the short SMI scales from the non-patient controls in direction of the clinical Axis I and Axis II samples (samples from validation of short SMI, [

60]). At the same time the sample showed considerable overlap with the scores of Axis I, but predominantly distinguishes from Axis II scores.

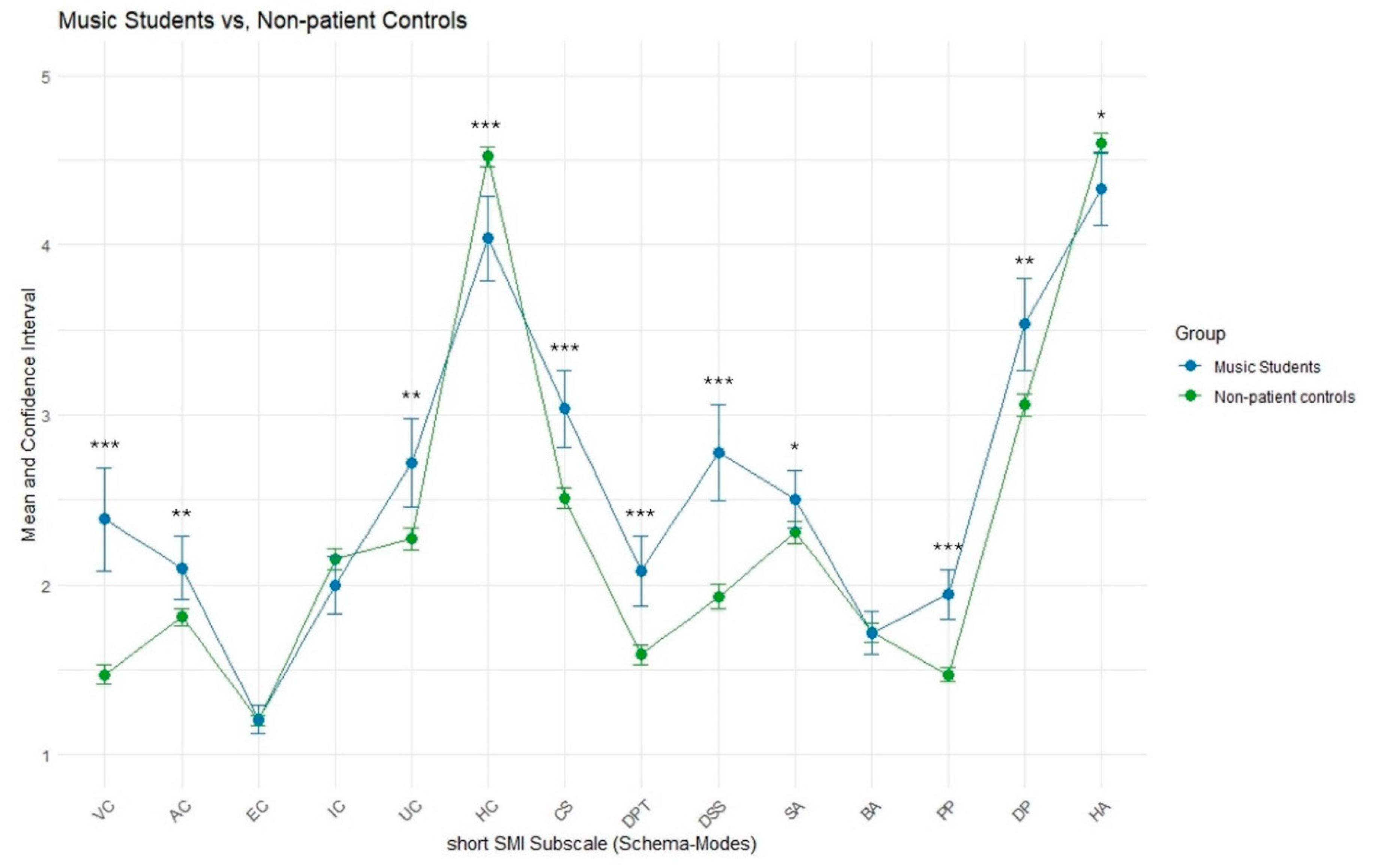

Music students scored higher on all maladaptive modes except the enraged child (EC) and the impulsive child (IC) modes as well as the bully & attack (BA) coping mode than the non-clinical population (see

Figure 1), reflecting worse coping with emotional triggers. Furthermore, significantly reduced adaptive modes (Healthy Adult, HA, and Happy Child, HC), reflect limited resources in adequate coping strategies. Considering Cohen’s d effect size categorization [

79] Vulnerable Child (VC), Compliant Surrender (CS), Detached Protector (DPT)and Detached Self Soother (DSS) Coping Modes as well as Punishing Inner Critic (PP) show large effect sizes; Angry Child (AC), Undisciplined Child (UC), Self-aggrandizer (SA) and Demanding Inner Critic (DP) yield medium effect sizes as do the reduced adaptive modes Happy Child (HC) and Healthy Adult (HA).

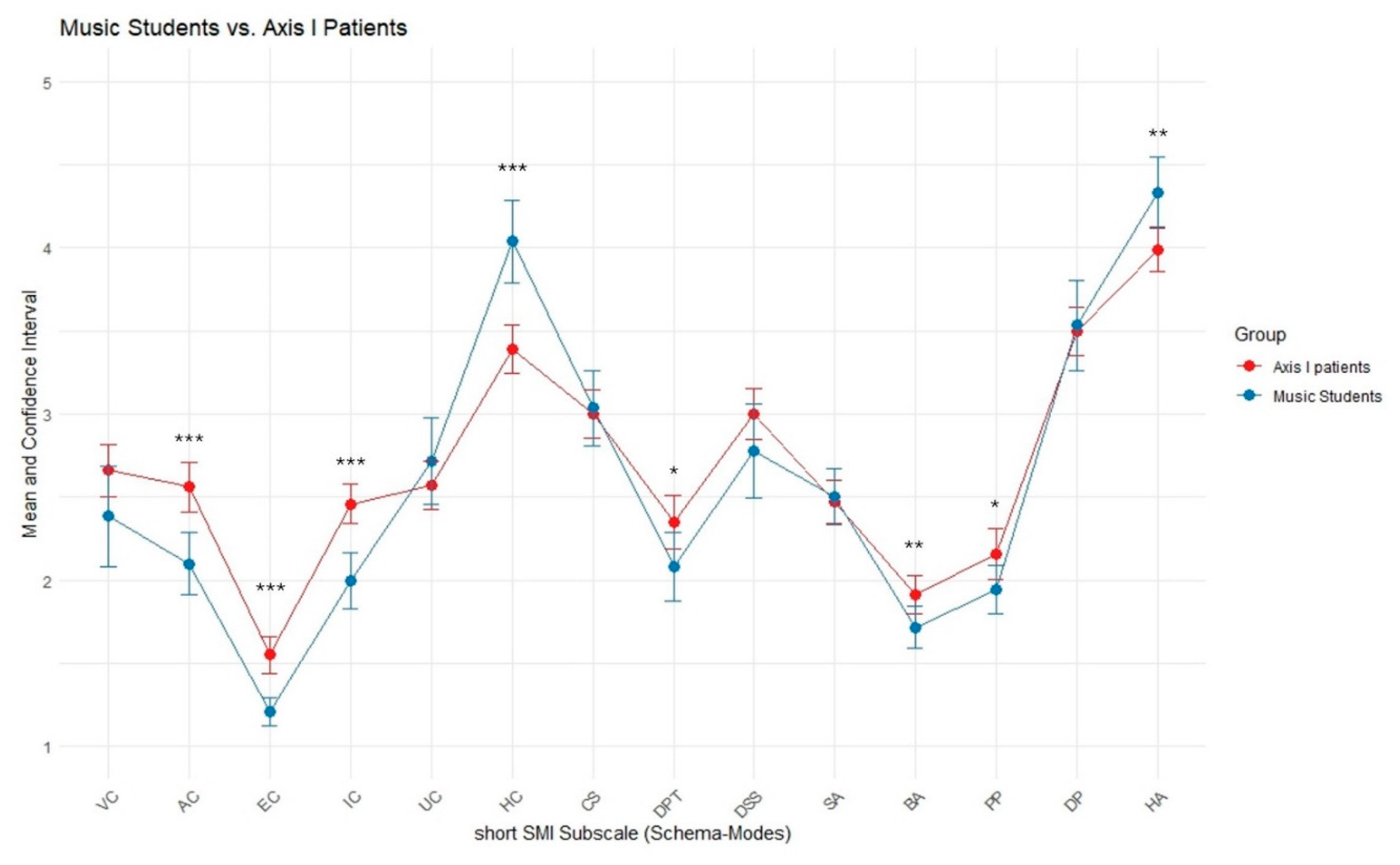

Compared to Axis I patients, music students reached similar, i.e. significantly non-different, scores on Vulnerable Child (VC), Undisciplined Child (UC), Compliant Surrender (CS), Detached Self Soother (DSS), Self-aggrandizer (SA) and Demanding Inner Critic (DP) (see

Figure 2), reflecting similar occurrence of these maladaptive emotional, cognitive and behavioral (coping) states as compared to these clinical patients. However, the present sample exhibited significantly lower scores (i.e. reduced occurrence of) on several other maladaptive modes than the Axis I patients: Angry Child (AC), Enraged Child (EC), Impulsive Child (IC), Detached Protector (DPT), Bully & Attack (BA) and Punishing Inner Critic (PP).

Furthermore, music students exhibited significantly higher scores on adaptive modes (Healthy Adult, HA, and Happy Child, HC), showing that the participants in the sample have more availability of positive resources than Axis I patients – although less than the non-clinical control group (see above).

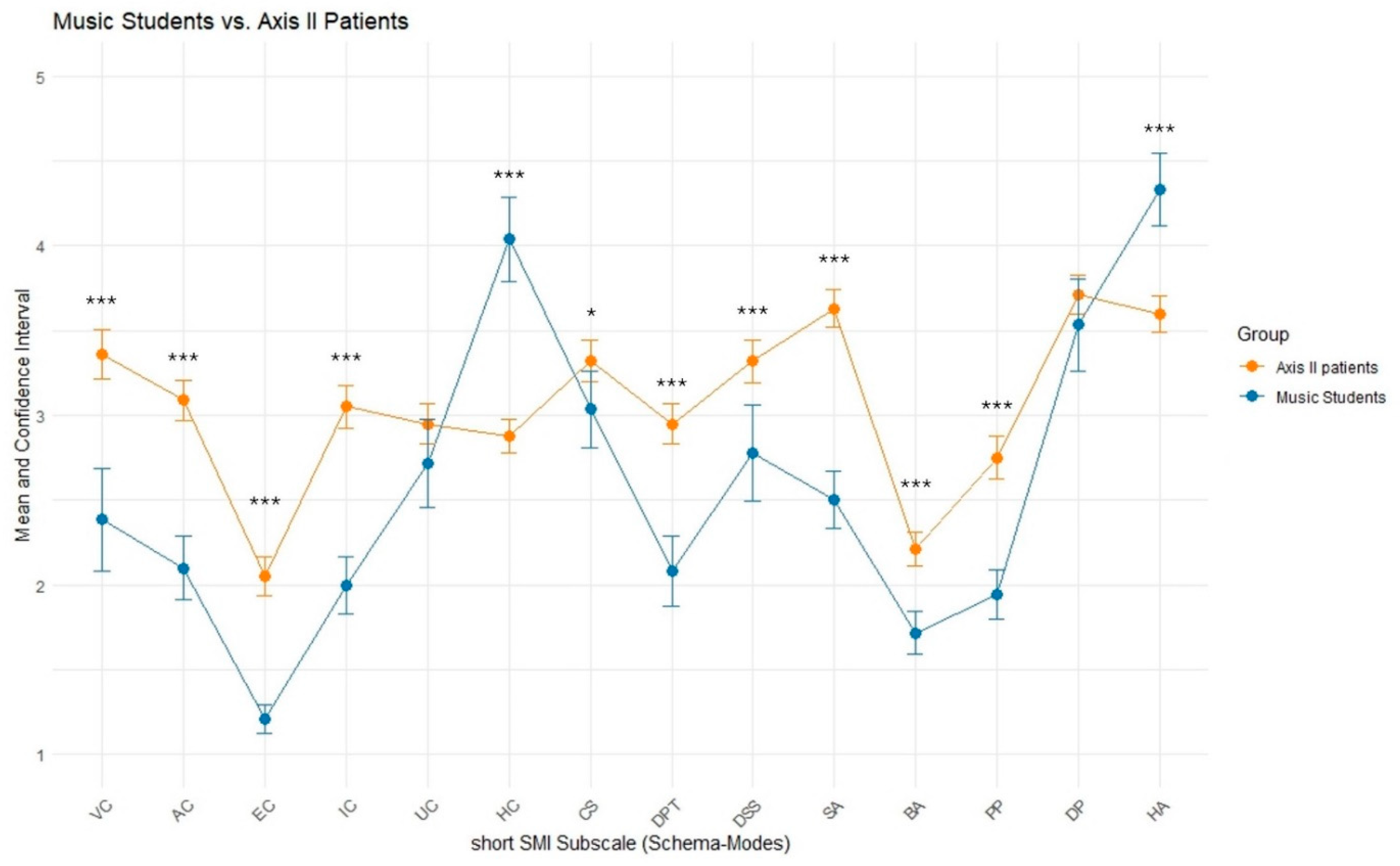

Compared to Axis II patients, music students reached similar, i.e. significantly non-different, scores only on Undisciplined Child (UC) and Demanding Inner Critic (DP) (see

Figure 3), reflecting similar occurrence of these two maladaptive states as compared to these clinical patients. On all other maladaptive modes, the present sample exhibited significantly lower scores (i.e. reduced occurrence of) than the Axis II patients.

Furthermore, music students exhibited significantly higher scores on adaptive modes (Healthy Adult, HA, and Happy Child, HC), showing that the participants in the sample have more availability of positive resources than Axis II patients – although less than the non-clinical control group (see above).

3.2. Internal Consistency of the shortSMI Subscales

The internal consistency of the Short-SMI subscales in the present sample was generally good to excellent (following the guidelines of Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; [

80]). The Vulnerable Child (VC) mode showed very high reliability (α = 0.93, average r = 0.55), followed by Happy Child (HC, α = 0.89, r = 0.46) and Healthy Adult (HA, α = 0.86, r = 0.37). Other subscales showed good reliability: Detached Protector (DPT, α = 0.83, r = 0.36), Detached Self Soother (DSS, α = 0.80, r = 0.50), Demanding Parent (DP, α = 0.82, r = 0.38), Angry Child (AC, α = 0.78, r = 0.25), Compliant Surrender (CS, α = 0.75, r = 0.30), Enraged Child (EC, α = 0.76, r = 0.32), Impulsive Child (IC, α = 0.72, r = 0.25), Undisciplined Child (UC, α = 0.72, r = 0.36), and Punishing Parent (PP, α = 0.70, r = 0.21). Two subscales showed lower reliability: Self-Aggrandizer (SA, α = 0.64, r = 0.15) and Bully & Attack (BA, α = 0.53, r = 0.14).

No internal consistency was calculated for the Short-SMI full score, as it combines heterogeneous subscales measuring distinct maladaptive and adaptive schema modes, and the small sample size relative to the large number of items would make the reliability estimate unstable.

Notably, the most reliable subscales (VC, HC, HA, DPT, DSS) also showed the clearest and most consistent effects in subsequent analyses, including cluster analyses, correlations with other scales, and differences compared to the validation study samples. The two low-reliability subscales (SA and BA), reflecting strongly externalizing behaviors, rarely appeared in the analyses, likely due to their low occurrence and socially undesirable nature in this sample. Overall, these reliability patterns provide additional confidence that the observed results for the majority of subscales reflect meaningful individual differences in schema modes among the music students.

3.3. Interrelation Between Schema Modes and HIL Scale

After reversing negatively poled items, participants in the sample on average scored low-medium (mean = 28.87, sd = 5.24) on the HIL scale. Although no general norms exist for the HIL scale, previous studies with music students and teachers reported mean scores between approximately 30 and 33, which can be considered as reflecting moderate to good coping [

25]. By contrast, pre-intervention values in music teachers (M = 26.8) and advanced students (M = 24.6) were lower, with improvements to around 29–30 after intervention [

78]. In this context, the present sample’s mean of 28.9 can be interpreted as slightly lower but still within an average to moderate-good range of coping and above the pre-intervention levels reported for teachers and advanced students. There was no difference between the HIL scores of female (mean = 29.07, sd = 5.05) and male (mean = 29.79 , sd = 4.66) musicians (t(27.77) = 0.46, p = 0.649 n.s.), with not enough data available for participants who selected gender “other/prefer not to say”.

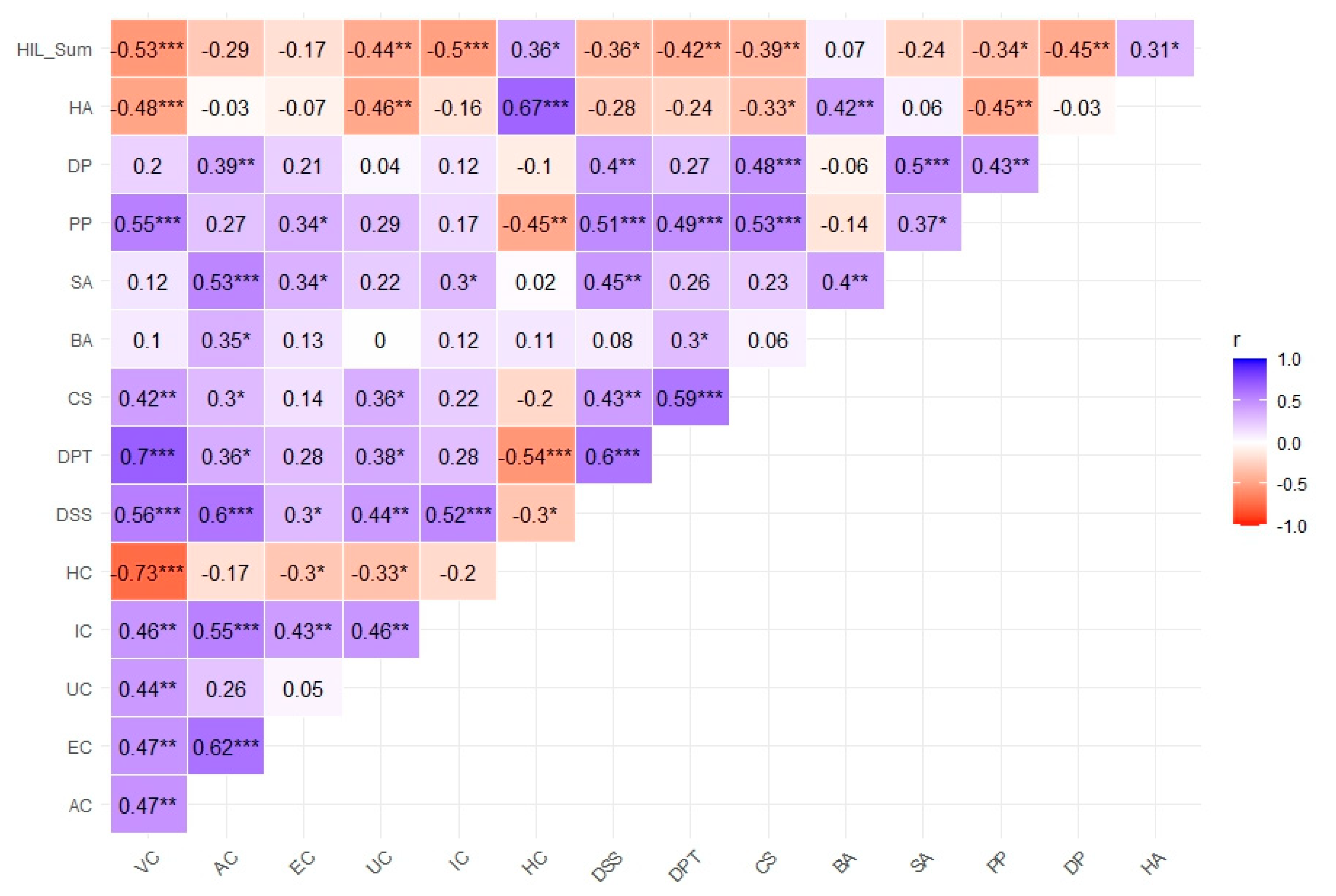

All maladaptive Schema Modes of short SMI were negatively correlated with HIL Sum Scores: The higher the score on the respective maladaptive modes (see

Figure 4), the lower the scores on the HIL Sum Score, indicating worse capabilities to cope with life as a musician

. Solely modes related to rage & anger (EC enraged child, AC angry child & BA Bully & Attack) did not yield significance w.r.t correlation with the HIL sum score. In contrast, high expression on Happy Child (HC) and Healthy Adult (HA) were positively correlated with HIL Scores (r = 0.36, p < .015 respectively r = 0.31, p < .38). Consequently, higher scores on these positive, adaptive schema modes were associated with better coping with life as a musician in the sample.

Interrelations between the SMI Schema Modes reflect predictions by Schema-Theory. Emotional triggers usually lead to activation of emotional child modes, cognitive parent modes (inner critic) and a maladaptive behavioral coping response. Only in case of sufficient resources of the “healthy adult” (HA), activation of maladaptive coping responses is reduced and the intensity of emotions and cognitions by child and parent modes can be reduced. It is especially noteworthy, that a high negative correlation between “happy child” (HC) and “vulnerable child” (VC) modes exists (-0.73, p < .001) next to smaller negative correlations between HC and other child modes (see

Figure 4). Furthermore, the VC mode shows strong correlations with all other maladaptive child modes (AC, EC, IC and UC). It is also closely linked to ‘freeze’ and ‘flight’ coping responses (CS Compliant Surrender, DPT Detached Protector, and DSS Detached Self-Soother). In addition, the VC mode is associated with punishing self-talk (PP Punishing Parent Mode), which often manifests as intense negative cognitions such as self-hate and vulnerable feelings of inferiority, shame, or worthlessness. This is also indicated by the high correlation between PP and VC in comparison to the other child modes with emotions more directed externally (anger, impulsiveness). Conversely, those outwardly directed child emotions of the AC (angry child) are exclusively correlated with the demanding parent mode (DP). Furthermore, high scores on maladaptive child and parent modes – reflecting frequent occurrence of these stages in the participants – are related to increased occurrence of maladaptive coping responses of at least one category, with the “freeze” and “flight” states being the most frequently experienced states.

3.4. Clustering Analysis: 3 Distinct psychOlogical Profiles of Music Students

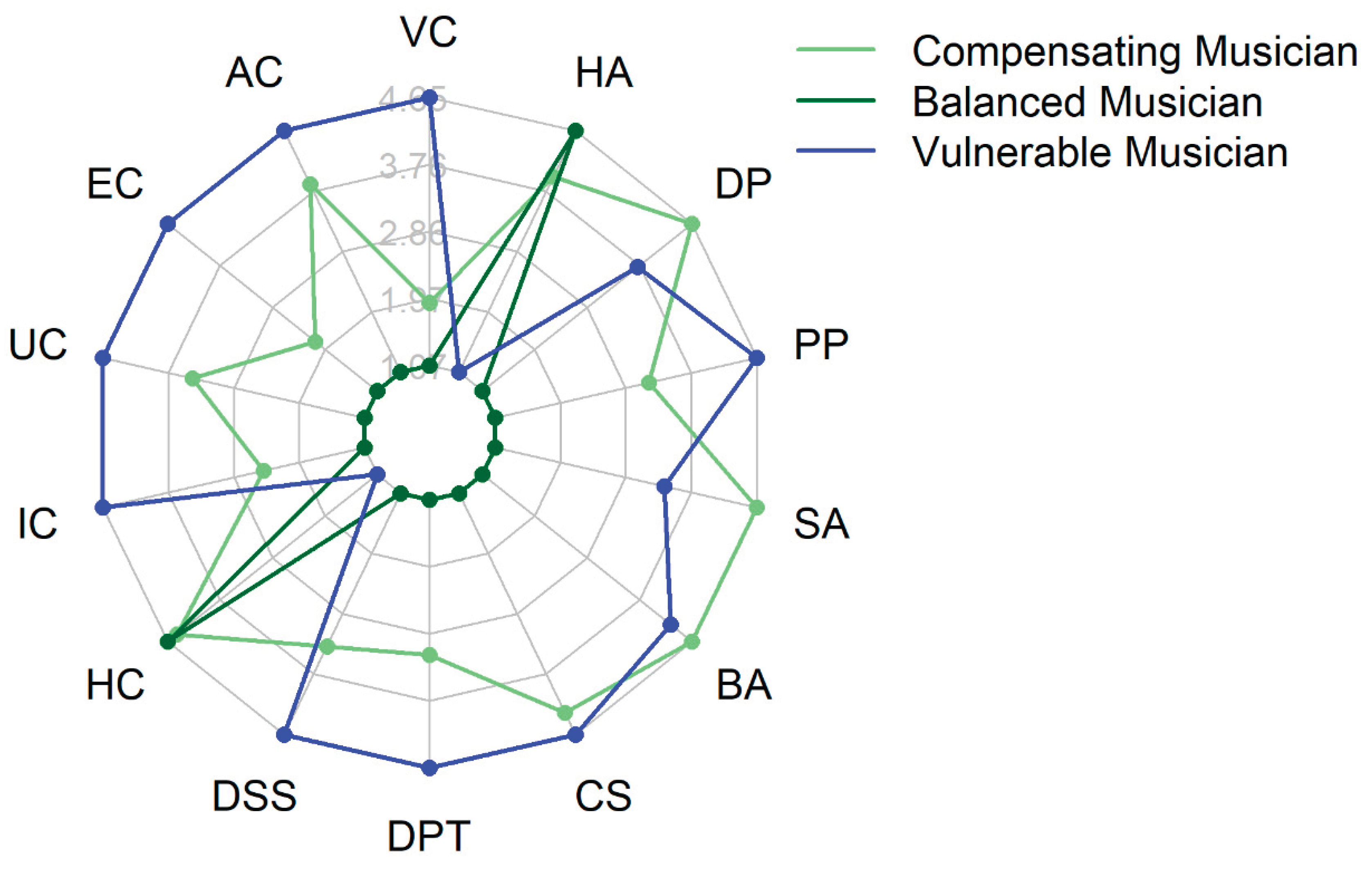

To investigate, whether specific psychological and coping profiles of music students exist, we performed an exploratory cluster analysis on the short SMI sub scores. The Within-Sum-of-Squares (WSS) plot showed a monotonic, exponential decrease of WSS for increasing cluster size with a visual estimation of an “elbow” at around 3 Cluster. The 3 Cluster solution was confirmed by the dendrogram of the exploratory hierarchical cluster analysis and is an adequate number of clusters for a sample size of N = 46.

The three obtained clusters significantly differ on HIL sum scores (F(42,2) = 8.216, p < .000974, η² = 0.281) with Cluster 1 (N=21, Δ mean= -7.21, CI [-11.79, -2.638], p < .010) and Cluster 3 (N= 10; Δ mean= -4.81, CI [-0.996, -8.623], p < .001) showing lower overall capability to cope with the life of a musician compared to Cluster 2 (N=14; compare

Table 3). The distinguishing correlation between Cluster number and HIL Score as well as the characteristic profile of the presence and intensity of maladaptive, respectively adaptive (HC, HA) short SMI sub scores (Schema Modes) indicate a meaningful cluster analysis (see

Table 3). The radar plot profiles displayed in

Figure 5 for each group are based on the means of the respective variables for each cluster level, scaled relatively between SMI modes and cluster.

3.5. Inner Self-Talk

Free responses on open-ended questions were analyzed in a two-step lexical approach: 1) Translation of the individual responses in nominalized expressions and 2) categorization of these expressions into descriptive categories. Finally, the frequency of the occurrence of the categories across the sample was counted for each question (see

Table 4).

Apart from physical (e.g. pain) related issues, most frequently mentioned complaints (Question 1) relate to destructive self-talk and expectations of self and others as well as topics of social interaction and organization. The latter aspect is strongly reflected in the responses to Question 2 “If you have/have had problems with a teacher or orchestra or chamber music partner currently or in the past, what problems were they?”. Most frequent categories related to social communication and interaction issues within music ensembles and between music teacher and music student.

During practice, rehearsal, and stage situations, the most frequently reported negative thoughts and feelings fell into four descriptive categories: 1) self-doubt 2) feeling of inferiority/insufficiency 3) externally oriented worrying (comparison/opinion of others) and 4) self-critical thoughts of demanding, punishing and hyperfocussing type. Nevertheless, several participants mentioned joy/pleasure, goal and process orientation, connection with others through music and flow states among others as positive resources respectively thoughts and feelings on stage.

Responses on open-ended questions did not differ in content between the three clusters, although we have to consider the small sample size in each cluster and the design of the questions as voluntary. The summary above thus provides a descriptive overview of typical issues, complaints, and inner self-talk among music students, rather than a quantified comparison of positive versus negative thoughts or relative frequencies of complaints. .

4. Discussion

The application of the Short Schema-Mode Inventory (SMI, [

60]) in this study marks a novel approach in psychological research within music students, providing valuable insights into their schema modes and their psychological profiles compared to non-clinical controls and Axis I and II patients from representative samples reported in [

60]. The findings suggest that music students may exhibit scores with maladaptive child modes (VC, AC and UC modes) and coping modes significantly different from non-patient controls, aligning more closely to Axis I patients and in-part overlapping with Axis II patients for maladaptive modes. This is consistent with the monotonic increase of symptom severity with higher maladaptive short SMI scores reported in [

60] and may indicate that music students, while per se not presenting clinical disorders, may experience emotional and psychological challenges between non-patient controls and clinical populations.

Particularly notable were the large effect sizes for Vulnerable Child (VC), Compliant Surrender (CS), Detached Protector (DPT), Detached Self-Soother (DSS), and Punishing Parent (PP) indicating substantial psychological distress compared to non-clinical patients (see

Table 1 for an overview over mode descriptions). These modes except PP plus the demanding parent (DP) inner critic furthermore were the modes that showed non-significant distinction from Axis I patients. This could hypothetically reflect subclinical or undiagnosed Axis I disorders like depression or anxieties, as patients with anxiety disorders and depression have been shown to have heightened early maladaptive schemata [

75]. However, this cannot be determined from the present study. Interestingly, VC scores in the short SMI validation study [

60] are strongly correlated with loneliness (Loneliness Scale, LS, .71), fearful attachment style in relationships (RSQ fearful attachment, .77) and Childhood Traumata (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, CTQ, .79) as hypothesized a priori by the authors of short SMI (60). The high scores on CS, DPT, DSS and PP in the present study furthermore correlated medium to high with the very same scales in [

60], although this was unexpected by the authors. These correlations of shortSMI [

60] raise the hypothesis that traumatic childhood experiences, attachment style and loneliness might contribute to the particular increased maladaptive modes in music students, but this cannot be inferred directly from the current study and warrants future investigation. Following this hypothesis, the present results in music students appear consistent with previous research indicating loneliness and social isolation in musicians [

81,

82,

83,

84] as well as traumatic childhood experiences as a risk factor of musician’s dystonia [

33,

39,

46]. Heightened early maladaptive schemata and schema modes have been found in patients with psychological trauma and PTSD [

85,

86]. Interestingly, Rezaei et al. [

87] found, that especially the schema “rejection” mediated adverse effect of childhood trauma on the development of depression, Banik et al. [

88] found the schemata “defectiveness” and “failure” linked to depression and Dutra et al. [

89] found increased suicidality in trauma patients with heightened scores on both “defectiveness”, “failure” and “social isolation” schemata. Given that experiences of rejection and feeling inferior or defective compared to other musicians are reported in this study (see section “Inner Self Talk” below) and common in the highly competitive performance industry of professional musicians, e.g. in competitions or engagements for concerts and collaborations with artist managers and recording labels, stress and pressure created by real or imagined rejection or inferiority could potentially trigger early maladaptive schemata in musicians with trauma history ore previous adverse experiences with unconstructive critics. Such processes might contribute to more pronounced emotional reactions (child modes) and more maladaptive coping strategies (fight, flight, freeze) such as perfectionism, procrastination, self-soothing with addictive behavior, sublimination or narcissistic attitudes, which in turn could affect wellbeing or career development. However, this remains speculative until studies on schema-mode-structure of musicians with trauma history are being investigated.

Reduced scores in adaptive modes (Healthy Adult (HA) and Happy Child (HC)) compared to non-clinical controls – although significantly higher than in both clinical populations – may point to limitations in positive coping strategies, suggesting that supportive interventions could be beneficial. However, research on schema-focused interventions is needed to confirm this hypothesis. While there is only non-significant overlap with Axis II patients (personality disorders) on UC (Undisciplined Child) and DP (Demanding Parent) of [

60], the results have to be interpreted carefully, since people with personality accentuations, e.g. narcissistic tendencies, usually do not voluntarily participate in psychological studies or offerings because of their belief, that others are the problem.

The HIL Scale results revealed a lower average level of coping among the music students, with no significant gender differences. This contrasts previous findings by [

25] who investigated psychological distress in longitudinal study of 105 first-year students at three Swiss music universities and found greater increase in the tendency to exhaustion among women compared to men in the first year of their studies. Whether these differences can be explained by possibly greater willingness to deny complaints in men remains unclear [

90]. In the present study, the mean HIL score of 28.9 was somewhat lower than the 31–33 typically reported for first-year students in earlier research [

25], but at the same time clearly higher than the pre-intervention values documented for teachers and advanced students [

78], which likely reflected groups with above-average psychological strain. This suggests that our sample demonstrated slightly reduced coping resources compared to typical student cohorts, but not to the extent observed in pre-intervention groups with elevated distress.

Notably, maladaptive Schema Modes were negatively correlated with HIL scores, underscoring the impact of psychological profiles on musician-specific coping capabilities. This finding suggests that when musicians are frequently operating from maladaptive emotional and behavioral patterns (e.g., feeling overwhelmed, self-critical, or detached), their ability to cope with life as a musician, such as confidence in stage situations, satisfaction with performance or bodily functions (e.g. posture, breathing, movement control etc.) while playing or feeling capable of handling one's studies, is significantly hindered. This is particularly noteworthy for musicians, as their profession often involves high-pressure performance situations where effective coping is crucial for sustained well-being and career longevity. Positive correlations between HIL Scale and HC and HA modes indicate that the presence of adaptive modes enhances music specific coping, reflecting Schema Theory's predictions of reduced maladaptive coping responses with stronger Healthy Adult resources. Specifically, these results imply that musicians who can access their Healthy Child (HC) mode for joy and spontaneity, and their Healthy Adult (HA) mode for emotional regulation, self-reflection, thoughtful decision-making and self-nurturing, are better equipped to manage the unique stressors of their musical lives. While the general principle that adaptive psychological resources support coping aligns with broader Schema Theory (as evidenced by the reported reverse relationship between HA and HC and the severity of Axis I and Axis II symptoms in general populations [

60] in the validation of short SMI), our study specifically extends this understanding to the domain of music performance. The purpose of presenting these correlations is to demonstrate how established schema theory constructs manifest within the distinct context of music students, highlighting the practical relevance of schema modes for understanding and potentially improving their coping mechanisms in a performance-oriented field.

The interrelation between maladaptive scores underscore the dynamic interplay within the schema mode system, where emotional triggers frequently activate maladaptive Child modes, inner critics (Parent modes), and subsequent maladaptive coping responses. This observed interrelation between several Child modes (Emotions), Parent modes (Cognition, internalized Beliefs), and coping behaviors is typical for schema activation, as described in the introduction. Crucially, the presence of a robust Healthy Adult mode appears to mitigate these maladaptive reactions, allowing for a reduction in the intensity of distressing emotions and cognitions, while the Vulnerable Child mode emerges as a central driver of psychological distress and dysfunctional coping.

The patterns of internal consistency observed in the Short-SMI subscales provide meaningful context for interpreting the results. Subscales with high reliability, such as Vulnerable Child (VC), Detached Protector (DPT), Detached Self-Soother (DSS), Happy Child (HC), and Healthy Adult (HA), were not only measured consistently but also corresponded to the modes showing the strongest effects across analyses, including cluster membership (see section 4.1) and correlations with coping (HIL) scores. This may suggests that these consistently measured modes are central to characterizing emotional vulnerability, coping strategies, and psychological resources in music students.

In contrast, two subscales—Self-Aggrandizer (SA) and Bully & Attack (BA)—showed low reliability. This may reflect limited variance in these socially undesirable behaviors rather than poor measurement quality; socially desirable responding or perceived stigma could have led participants to endorse only some items within these scales, producing inconsistent response patterns. Taken together, these findings highlight that the most reliably measured and frequently expressed modes are the most informative for understanding the psychological profiles of music students, while less frequently expressed, externalizing modes require cautious interpretation.

4.1. Clustering Profiles: Identification of Psychological Subtypes

To investigate whether specific psychological profiles exist among music students, we performed an exploratory cluster analysis on the short SMI sub scores. The analysis revealed three distinct profiles: "Balanced Musician" (N=14), "Compensating Musician" (N=10), and "Vulnerable Musician" (N=21) (compare

Figure 5).

The "Balanced Musician" cluster showed the highest overall coping capability, characterized by lower scores on maladaptive modes and higher scores on adaptive modes. These musicians maintain a stable emotional state, leveraging positive coping strategies effectively.

The "Vulnerable Musician" cluster demonstrated the most significant psychological distress, marked by high scores in maladaptive child and passive coping modes (“Freeze”, Flight”) and low scores in adaptive modes. These individuals have frequent and intense negative emotional states which they try to avoid by e.g. fleeing the stressor or pleasing others (interpersonally or by musical perfectionism). These music students may benefit from more comprehensive support comprehensive support to address their emotional vulnerabilities effectively. Further research is needed to determine the extent and form of such interventions.

The "Compensating Musician" cluster exhibited medium levels of maladaptive modes and slightly lower scores on adaptive modes, reflecting a group that employs compensatory strategies to manage their emotional and psychological challenges superficially. These musicians often rely on externalizing coping behavior (“Fight”, e.g. self-aggrandizing, “bully & attack”) and validation by others (“Freeze”, e.g. CS, compliant surrender) to navigate their stressors and perform in the short term. Although they have more healthy resources (HA, HC) than “vulnerable musicians”, they may be at risk of decompensating if stressors increase or resources shrink or when success fails to materialize. Compared to “vulnerable musicians”, “compensating musicians” report fewer emotional child modes. This may indicate either weak connections to their own emotions or a bias in reporting due to the desire to be seen as competent and strong.

Hypothesizing about a potential relation to performance related stress and anxiety, the results of the cluster analysis are in line with Spahn and Krampe’s study [

27] and may suggest, that “Balanced Musicians” show similarity to the Type I MPA group (presumably low MPA, common Lampenfieber, [

27]) with high self-efficacy and adaptive coping, while “Compensating Musicians” show increased performance stress but still have strategies to cope with it and regulate themselves during performance (presumably high MPA at the beginning of the performance, [

27]). “Vulnerable Musicians” are in danger of getting into a vicious circle on stage by insufficient coping strategies and emotional regulation (presumably Type II MPA, that worsens during performance, [

27]). Research is needed to investigate the relationship between MPA severity and type and schema-mode expression.

4.2. Inner Self-Talk: Qualitative Insights

The analysis of free-response questions revealed common themes related to physical pain, self-criticism, social interaction, and organizational issues. Negative self-talk and self-doubts were prevalent, especially during musical tasks, indicating a need for interventions addressing destructive inner dialogues. These reports reflect the heightened demanding and punishing parent modes (DP and PP) in the study sample. A considerable number of subjects mentioned difficulties in social communication and interaction with teachers, conductors and colleagues as distressing factors. Social relationships is one of the most important factors in predicting wellbeing and healthy ageing in the general population [

91,

92,

93].This is especially noteworthy as Ascenso et al. [

94] identified the “shared nature of music making” and the “oneness in performance with others” as crucial for the experience of meaning and purpose in professional musicians. Furthermore, emotional distressing student-teacher relationships are frequently related to mental health issues in the further course of the musical career and traumatic familiar or pedagogical experiences may contribute to the risk of musician’s dystonia [

33]. Despite the subjective quality of these reports that cannot be validated objectively, accusations of lacking respect or pedagogical qualification of teachers as well as sexism and discrimination in teacher-student relations and music ensembles reflect perceived emotional abuse and distress.

Sexual and emotional abuse among students is a recognized problem across educational contexts and is associated with long-term negative effects on wellbeing and development [

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100]. In music education, evidence shows that teacher-perpetrated abuse is common, with more than one-quarter of students reporting emotional abuse and up to 10% physical abuse in school music classes [

97]. Reported physical acts by music teachers included beating, pulling ears or hair, hitting a student’s head with instruments or rulers, and throwing objects, while emotional abuse ranged from harsh criticism, insults, and neglect to humiliating practices such as comparing a student’s voice to an animal sound, making fun of physical characteristics, or forcing peers to spit on a singled-out child [

97]. In higher education, qualitative research highlights similarly patterned emotional abuse embedded in classical music culture, including humiliation, harmful comparison, and verbal aggression [

98]. In contrast, peer-perpetrated bullying disproportionately affects music and theatre students, with male students being more vulnerable to physical aggression and female students to social/relational victimization [

100].

Positive responses of the participants highlighted resources such as joy, goal orientation, connection through music, and flow experiences. Such positive emotions are crucial for general wellbeing [

94,

101] and effective coping in dealing with performance anxiety [

26]. Especially, positive feelings can increase and stabilize internal resources and resilience by means of the broaden and build effect [

102]: positive emotions increase wellbeing and positive action repertoire, which in turn further increase wellbeing and resources. Furthermore, flow experiences [

103] and feelings of accomplishment and process orientation [

104] have been associated with increased motivation and creativity [

105,

106,

107,

108].

4.3. Implications for Prevention and Interventions at music school

The identification of distinct psychological profiles among music students underscores the need for personalized coaching interventions. "Balanced Musicians" may benefit from course programs aimed at maintaining and refining their existing coping strategies. Coaches can incorporate advanced techniques for stress management, performance optimization, and emotional regulation. Encouraging practices that emphasize balance and well-being, such as regular physical exercise, structured practice routines, and social support, can help these individuals sustain their adaptive coping mechanisms. Such interventions are already implemented by a wide range of music universities via the course programs in the field of music physiology and musician’s medicine (e.g. stage training, mental training, or body focused programs such as Alexander Technique or Dispokinesis). Whether the increasing efforts at conservatoires with regard to prevention and therapy will be able to compensate for the frequent musician-specific complaints or only alleviate them remains to be seen at the present time. Initial empirical values have been documented, at least for conservatoire training [

28,

109,

110].

For "Compensating Musicians," strategies could focus on building internal resilience and self-validation. This group may benefit from techniques of schema-focused coaching that strengthen adaptive modes (HA, HC) and enhance internal coping mechanisms, such as mindfulness practices, resilience training, and schema-focused group workshops as suggested by Wenhart [

53]. Similarly, "Vulnerable Musicians" benefit from such techniques but some may need comprehensive support in terms of individual psychological coaching or even long-term psychotherapy. Dedicated training for both groups should focus on dealing with negative inner self-talk on stage, but equally during practice and in ensemble playing. Imaginative Techniques, role plays on chairs between internalized voices and exercises to increase self-confidence should be central to workshops and coaching to increase self-efficacy and adaptive coping as suggested by [

53] and in accordance with the broaden & build effect [

102] and the self-determination theory [

106,

107]. Furthermore, psychoeducation on the interaction between biological predisposition (e.g. stress sensibility, nervous system activity), present and past social system and psychological factors (inner self talk, beliefs etc.) may be taught to enable music students to individually reflect and work on their unique levers.

A comparable voluntary workshop as suggested by [

53] was conducted for the participants of the present study as a pilot workshop and yielded overall positive feedback. More than twice as many participants enrolled in a personal 1:1 coaching and greatly appreciated the offer, underlining the need for a confidential space to target individual topics with a psychological expert. Such coaching with psychologically educated personnel could represent a promising approach to help musicians deal with individually experienced traumatic or non-traumatic, emotional in past personal or musical life, as intense traumatic, or reoccurring similar emotional situations create schemas that are automatically triggered on stage or in musical interaction with others, as soon as the brain detects a similar emotional threat.

Lastly, cooperations with external psychological or psychiatric clinics and implementing peer-support groups could help to facilitate access to mental health support and reduce stigma.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

A limitation inherent to the online study design is the inability to control for the representativeness of the samples. While we made sure to distribute the questionnaire widely across the participating Swiss music universities, whether students did or did not take part in the study might be dependent on their personal affection with the topic. On the one hand, students who took part in the study may have been especially interested in coaching or therapy topics anyway or may even have perceived instability and a need for therapy in themselves. One the other hands, students who did not take part might have had felt too much a stigma with the topic or feared negative consequences in their studies or towards their teacher despite the anonymous character of the survey.

Another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size (N = 46), which reduces the stability and generalizability of both the cluster analysis and reliability estimates. While three distinct clusters could be identified, their interpretability and robustness are constrained by the limited number of participants. The high dropout rate of approximately 59% further exacerbates these limitations, potentially introducing significant non-response bias if those who dropped out differ systematically from the music students who completed the survey. This substantial attrition might reflect issues with survey length, perceived relevance to music students, or the sensitive nature of the Short-SMI questions, leading to a less representative sample. Similarly, two Short-SMI subscales (Self-Aggrandizer and Bully & Attack) did not reach adequate internal consistency. This may be partly due to the low frequency and socially undesirable nature of these behaviors, which could have led participants to endorse only some items within these scales, resulting in inconsistent responses. Consequently, findings for these subscales should be interpreted cautiously, and future studies with larger, more diverse samples are needed to validate the cluster solution and reliability patterns. Furthermore, it could be that the students investigated would have performed more similarly to (healthy) purely student control groups in the non-musical area than compared to the clinical norm controls of adults of the Schema Inventory (mean age in [

60] was 34 years, SD = 11.80, range 18–70). This could be hypothesized, because the phase of life as a student after leaving home is typically characterized by reorientation and upheaval [

111,

112]. While the comparison study [

60] investigated clinical and non-clinical samples with specifically assessed selection criteria, this was not possible in the character of an online study apart from self-reported mental and physical health. Additionally, comparisons with the published validation study samples were based solely on summary data, as raw data were not available, which means statistical interpretations are limited to descriptive reference rather than formal parametric tests. However, in the case of music students, a heterogeneous field of behavioral and experiential patterns can be assumed, even within the musical disciplines [

113]. Furthermore, first-year students at three universities of music were found to have significantly higher values for life satisfaction, social support and inner peace as well as for ambition and subjective meaningfulness of work compared to comparison groups of students of pedagogy and psychology. On the other hand, the ability to distance oneself from work and the striving for perfection were significantly lower than in the comparison groups mentioned [

114].

Another constraint of our study is the limitation of the comparison with clinical samples to the classification of DSM-IV and ICD-10 instead of DSM-V and ICD-11 categorization. Axis I refers to clinical disorders such as depression or anxiety, and Axis II refers to personality disorders. While these categories are now outdated in DSM-5/ICD-11, they are retained here because the Short SMI validation study used these classifications and provides large, clustered clinical samples that serve as a practical reference for interpreting the schema-mode patterns in our music student sample. The classification as Axis I and II is now a historical concept but was still used at the time of the development of the schema-mode-inventory [

60]. These categories of Axis I and Axis II disorders are no longer included in today's DSM-5 and are no longer systematically used in modern diagnostics - even if they are still occasionally used in clinical language because the terms have become commonplace. In older diagnostic systems such as ICD-10, a similar distinction is sometimes still made, although not explicitly in axis form.

Future studies should consider larger samples of cross-university cohorts to validate these findings and explore long-term impacts of schema-focused workshops dedicated to musicians with longitudinal designs. Furthermore, questionnaires that assess the underlying schemata e.g. YSQ (Young Schema Questionnaire) should be used, to identify whether common schemata such as “social isolation” or “rejection” or “failure” are specifically more prevalent in highly competitive populations such as music students/professional musicians or sport athletes compared to the general student or adult population. This would complete the picture of the related schema-modes presented in this research. Additionally, integrating clinical assessments of common physical and psychological diagnoses might offer deeper insights into the interrelation between schema-modes and musicians’ overall, long-term health, ultimately contributing to their holistic development. Especially the investigation of MPA and musicians’ dystonia as well as psychosomatic components in pain disorders in relation to schemata and schema-modes may inform about the genesis and psychopathology of these disorders and improve individualization of treatment strategies.