1. Introduction

Eating disorders are neuropsychiatric disorders characterized by excessive preoccupation with and distorted cognition of food, weight, and body shape, resulting in recurrent abnormal eating behaviors and physical and psychological consequences [

1]. Given their physical sequelae and the relatively high mortality rate among psychiatric disorders [

2,

3], eating disorders rank among the most urgently needed psychiatric disorders to treat.

Eating disorders are a psychological disorder with a high prevalence among women [

1], which has more than doubled globally between 2000 and 2018 [

4]. In Korea, the number of patients diagnosed with eating disorders has increased by 41% over the past five years (from 6,612 to 9,317) [

5]. Interventions during adolescence have been shown to prevent the severity and chronicity of eating disorders, and treatment persistence has been shown to be good. In addition, unlike adults, adolescents can receive help and support from their parents, and parental involvement in treatment increases the likelihood of preventing long-term maintenance of dysfunctional eating patterns [

6]. However, the persistence of eating disorders in adulthood may be associated with greater difficulty in detecting symptoms, higher rates of disengagement from treatment, and a greater likelihood of persistent and chronic [

7], resulting in decreased responsiveness and persistence to treatment, which may lead to more severe symptoms of the disorder. Therefore, there is a need to focus on women in early adulthood who are more likely to have more severe and chronic symptoms than adolescents.

Psychotherapies such as Family Based Treatment (FBT), Interpersonal Psycho Therapy (IPT), and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are recommended for treating eating disorders [

8]. When examining the guidelines for eating disorder subdisorder, for adults with anorexia, psychotherapy focused on the eating disorders is recommended, with other psychotherapies available, including the Maudsley Model of AN for Adults (MANTRA), CBT, Specialist-Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM), and psychodynamic psychotherapy, which have shown significant effectiveness [

9,

10,

11]. In addition, effective treatments for anorexia may vary by age, with Family Based Treatment (FBT) with parental education recommended for children and adolescents, and treatments such as MANTRA, CBT, and SSCM for adults [

12].

A variety of psychotherapies are recommended to treat eating disorders, with CBT being more effective than other psychotherapies in treating bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder [

13]] and anorexia nervosa, which has been shown to be effective in adults and adolescents [

14], including weight gain [

15,

16]. Furthermore, CBT is one of the most effective evidence-based treatments for eating disorders and is recommended for treating eating disorders in adults [

17,

18] sought to develop a broader understanding of patients with eating disorders by emphasizing the core pathology shared by patients with eating disorders that is not seen in other psychiatric disorders, regardless of diagnosis, and by including four factors (clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem, intolerant mood, and interpersonal difficulties) that impede and maintain treatment for eating disorders.

Despite this, some people with eating disorders continue to suffer from ineffective CBT treatment or high dropout rates [

19,

20]. Failure to complete treatment is one of the factors limiting the effectiveness of eating disorder treatment [

21]. It is important to ensure that people with eating disorders are able to complete treatment. As with other mental disorders, early and rapid changes are key to long-term treatment outcomes for eating disorders [

22,

23,

24]. While CBT can be used to treat all types of eating disorders, it may not be the optimal treatment for anorexia and bulimia nervosa [

25].

Anorexia nervosa has a high dropout rate [

14,

26], and typically, only one-third to one-half of patients with ED achieve clinical remission after CBT treatment. Eating disorder patients also have high rates of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, such as non-suicidal self-harm [

27], mood disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol and substance use disorders, and personality disorders [

28]. In addition, inflexible and rigid personality traits [

29] and low emotional awareness [

30] can interfere with the ability to perform the tasks required in CBT treatment. These high dropout rates and high comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders make the treatment of eating disorders more challenging, suggesting the need for treatment models that address eating pathology in an intensive and integrated manner along with personality traits, emotional instability, and other comorbidities for those who cannot be helped by CBT [

31,

32].

Schema Therapy (ST) was developed by Young [

33] to treat clients with chronic personality problems who were unable to receive adequate help through traditional cognitive behavioral therapy. Schema Therapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of other serious and persistent psychological problems with personality traits, including personality disorders [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]; as an alternative to CBT for eating disorders [

42,

43], and research has also shown that Schema Therapy may be appropriate for treating eating disorders with co-occurring pathologies, including chronic eating disorders and personality disorders [

44,

45].

A growing body of research has shown the efficacy of Schema Therapy for eating disorders [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] emphasized the need for research and development to describe new subschema modes that may distinguish different psychopathology groups. Schema mode is an important concept in Schema Therapy, which refers to the “state” in which schemas are activated, i.e., the schemas and coping styles that are activated at a particular moment, rather than to individual characteristics. Schema modes can explain the rapid changes in emotional states and behaviors associated with affective instability [

41,

50], Adults with eating disorders have been shown to experience significantly higher levels of maladaptive coping modes than those without eating disorders [

43,

51]. It is important to identify the schema modes of people with eating disorders, because intervention strategies vary depending on which schema mode is activated.

Identifying factors that may influence eating disorder treatment outcomes can help improve therapeutic interventions [

32], but according to Grilo and Juarascio [

52], little progress has been made in this area, and some empirical research suggests that cognitive distortions, such as over-evaluation of weight/body shape, predict eating disorders [

53,

54]. Nevertheless, for patients with eating disorders who cannot be helped by CBT, a schema mode approach may be an alternative [

38], so this study incorporates Schema Therapy.

Schema Therapy proposes that psychological symptoms, disorders, and problems are caused by the development of maladaptive schemas as a result of core childhood needs, such as attachment, not being met in the childhood environment, in addition to the child’s temperament, and schema modes are triggered when these schemas are activated [

55]. Thus, environments that do not validate children’s emotions, such as authoritarian parenting behaviors, and environments with high levels of control with little acknowledgment of children’s autonomy can lead to psychological problems because they are less receptive to children’s emotional needs and are more likely to neglect children’s needs, resulting in chronic unmet emotional needs.

Previous studies examining the relationship between parental behavior and eating disorders have shown that low parental affection and high levels of control are important variables. Patients with AN were associated with less parental care and higher levels of control than the control [

56] and were associated with overprotective and unreasonably controlling fathers [

57], and low parental support in binge eating disorder patients [

58]. In addition, parenting attitudes (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive) have been shown to be associated with eating symptoms in children [

59]. Therefore, we hypothesized that authoritarian parenting behaviors (high control and low affection) would positively influence eating disorders.

Negative early experiences, such as authoritarian parenting behaviors, contribute to the formation of dysfunctional schemas and beliefs [

60]. Young [

33] suggested that individuals develop dysfunctional assumptions about weight and body shape as a means of compensating for dysfunctional core beliefs. In other words, individuals with eating disorders form dysfunctional assumptions (intermediate beliefs) that success and achievement must be related to weight and body size to compensate for core beliefs of powerlessness, lack of self-efficacy, defectiveness, failure, worthlessness, and lack of identity [

61], which are considered core pathologies that are only seen in individuals with eating disorders.

This means that people with eating disorders place undue weight on weight and body shape when assessing their self-worth [

62] and, which is a unique cognition held by people with eating disorders and is important to consider when treating eating disorders [

63]. Eating disorders are cognitive disorders [

64], and their core psychological theme, schemas, are deeply ingrained beliefs that are acquired early in life, repeated throughout life, and highly resistant to change ([

65]. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that authoritarian parenting behaviors would positively influence eating disorder beliefs (schemas).

Negative parenting experiences such as authoritarian parenting behaviors play an important role in shaping an individual’s core beliefs. If a parent exhibits authoritarian parenting behaviors that are unaffectionate and highly controlled, the child may partially internalize their parenting style, which can lead to maladaptive behaviors, such as dysfunctional eating behaviors, because the core beliefs that make up the self are likely to be irrational. In other words, individuals with disordered eating form dysfunctional assumptions (intermediate beliefs) that success and achievement must be tied to weight and body shape regulation and control in order to compensate for core beliefs of powerlessness, lack of self-efficacy, defectiveness, failure, worthlessness, and lack of identity [

61], and these dysfunctional beliefs are considered core pathology seen only in individuals with eating disorders.

Individuals with eating disorders place an inordinate amount of weight and body shape on their self-worth [

62], and individuals with eating disorders exhibit unusual beliefs that evaluate themselves based solely on their eating, body shape, or weight and their ability to maintain control over these factors [

18]. In addition, idiosyncratic beliefs about weight, body shape, food, and eating have been identified in both anorexia and bulimia [

66]. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that eating disorder beliefs would have a positive influence on eating disorders.

Maladaptive beliefs are maintained through maladaptive coping behaviors. Maladaptive coping modes include avoiding intolerable emotional states and cognitions by engaging in impulsive behaviors, such as binge eating, and overcompensating coping styles, such as restricting food, compulsive exercise, and calorie counting, to prevent intolerable emotions from being activated. These maladaptive coping styles serve to avoid activating distressing emotions or to maintain beliefs that alleviate negative emotions, but do not serve the individual in the long run. Schema modes are temporary emotional, cognitive, and behavioral states that respond to an activated early maladaptive schema such as surrender, avoidance, or overcompensation. Research has highlighted the importance of these coping styles and schema modes in the relationship between negative early experiences and disordered eating behaviors [

67].

This suggests that cognitive factors and coping styles should be considered alongside schema modes when treating eating disorders, and that considering schema modes may be particularly effective in interventions for eating disorders with complex comorbidities and personality difficulties [

69]. Maladaptive schema modes have been shown to mediate the relationship between early experiences and maladaptive schemas and eating disorder behaviors [

68], with overcompensation (perfectionistic overcontroller), avoidance (detached protector and detached self-soother), and surrender (compliant surrenderer) schema modes all playing important roles [

67]. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that eating disorder beliefs, the core pathology of eating disorders, would influence eating disorders through maladaptive schema modes.

With high mortality rates [

3], non-suicidal self-harm [

27], and high comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol and substance use disorders, and personality disorders [

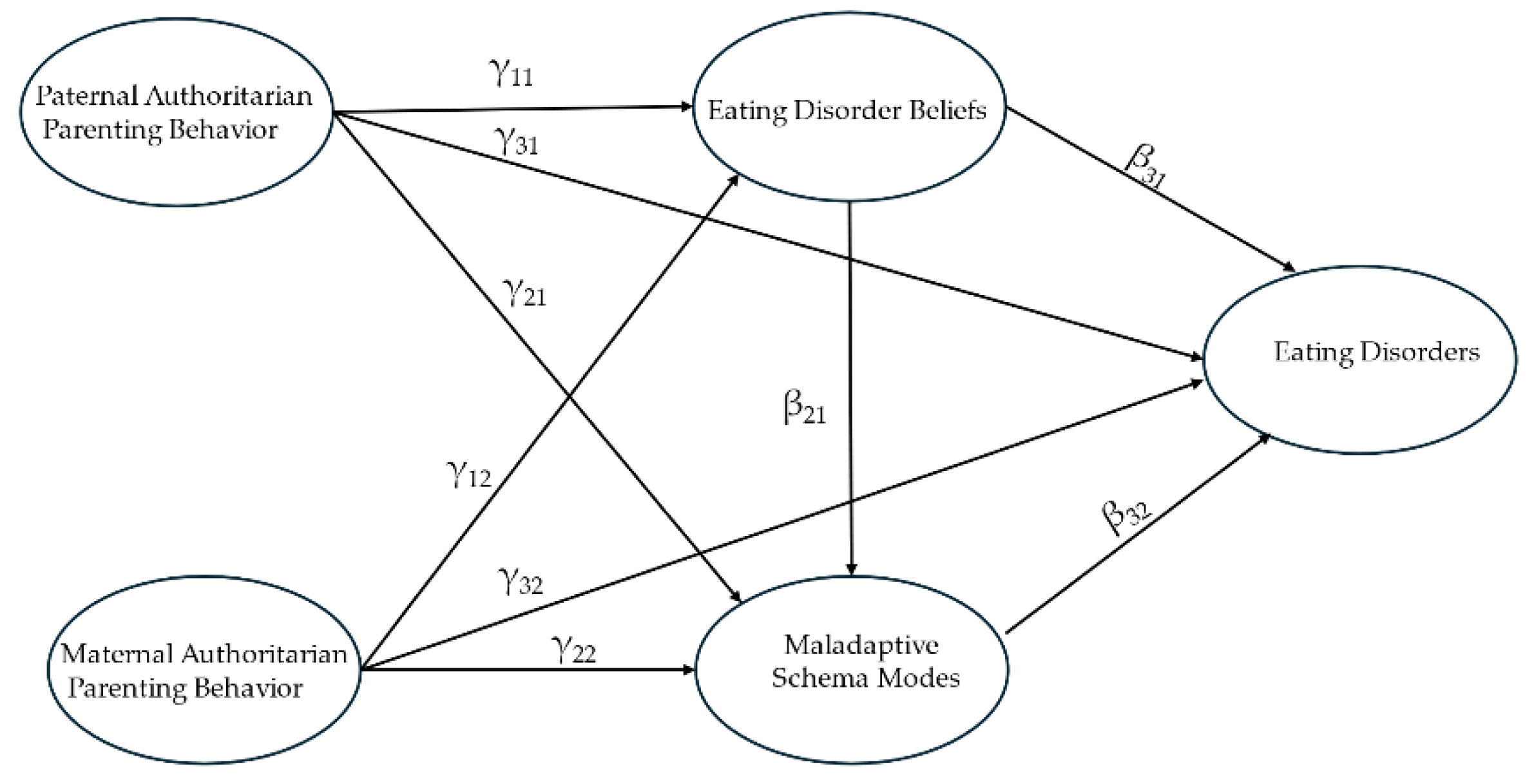

28], eating disorders are urgently needed but difficult to treat. In this study, based on the etiology of Schema Therapy and previous studies on eating disorders, we developed a hypothetical model (

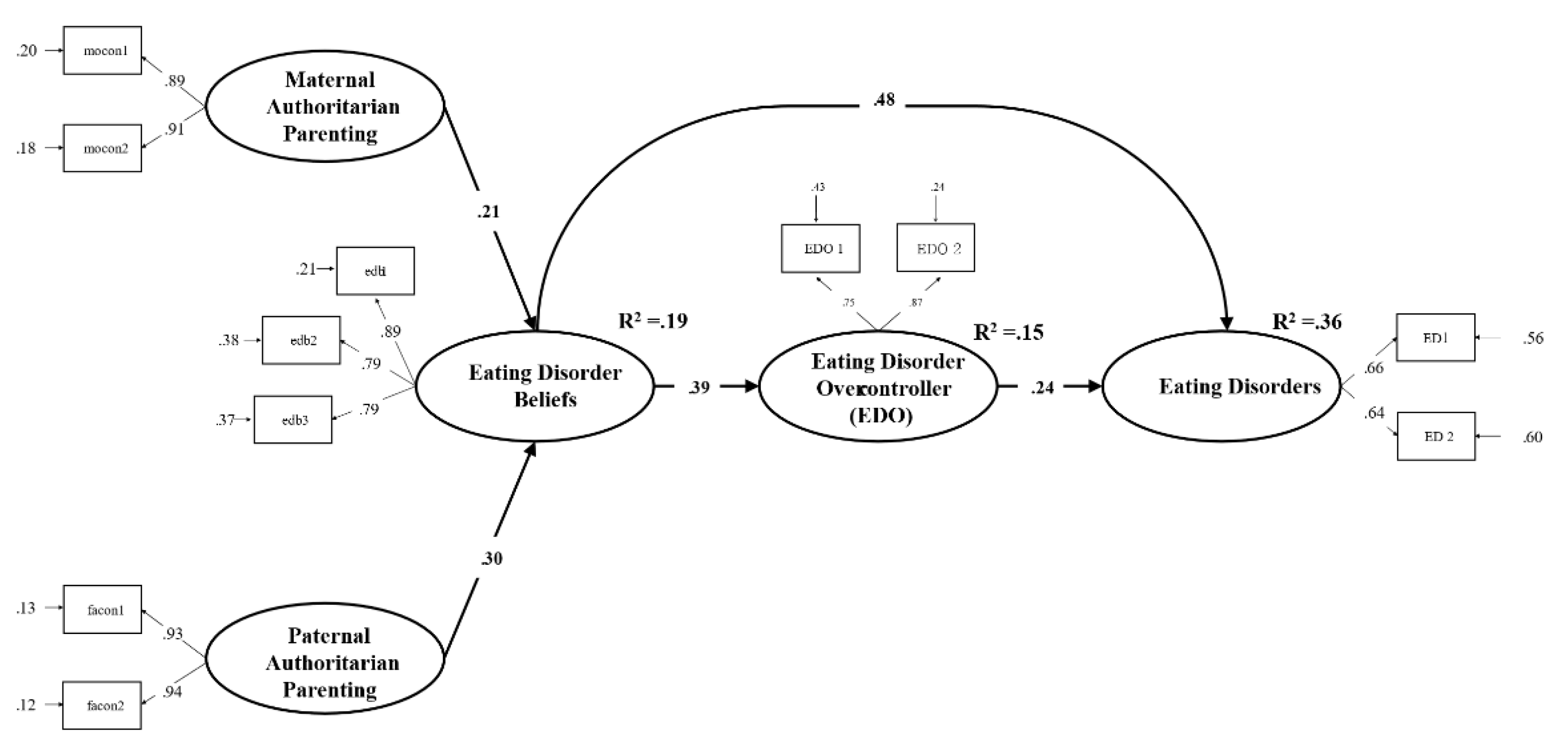

Figure 1) that suggests that authoritarian (controlling) parenting by fathers and mothers may directly cause eating disorders or may cause eating disorders through psychological mechanisms that lead to the development and expression of eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes, and tested it to provide a more diverse perspective and understanding of eating disorders and provide useful implications for therapeutic interventions.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of this study.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of this study.

4. Discussion

This study examined the role of eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes in the relationship between authoritarian parental behavior and eating disorder symptoms among women in their 20s with eating disorders. It was discovered that both maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors had an indirect effect on eating disorders through eating disorder beliefs and unhealthy schema modes.

The results confirmed in this study are summarized as follows

First, the mediation path of eating disorder beliefs was significant in the relationship between authoritarian maternal and paternal parenting behavior and eating disorders. This finding suggests that authoritarian maternal and paternal parenting behaviors influence eating disorders through eating disorder beliefs. This suggests that beliefs in eating disorders play an important role. Eating disorder beliefs are conditioned beliefs [[

91], Cooper et al.’s study (as cited in [

92])] that are associated with core schemas, such as early maladaptive schemas [

61], This supports the CBT theory that the etiology of eating disorders is cognitive, which suggests that addressing eating disorder beliefs is important in treating eating disorders. There are six important ways to address eating disorder beliefs [

93]. First, identifying excessive preoccupation with weight/size and its consequences; second, emphasizing the importance of other aspects of self-evaluation; third, addressing body image confirmation and avoidance; and fourth, dealing with “fat feelings.” Fifth, exploring the sources of self-evaluation, and finally, learning to deal with eating disorder minds.

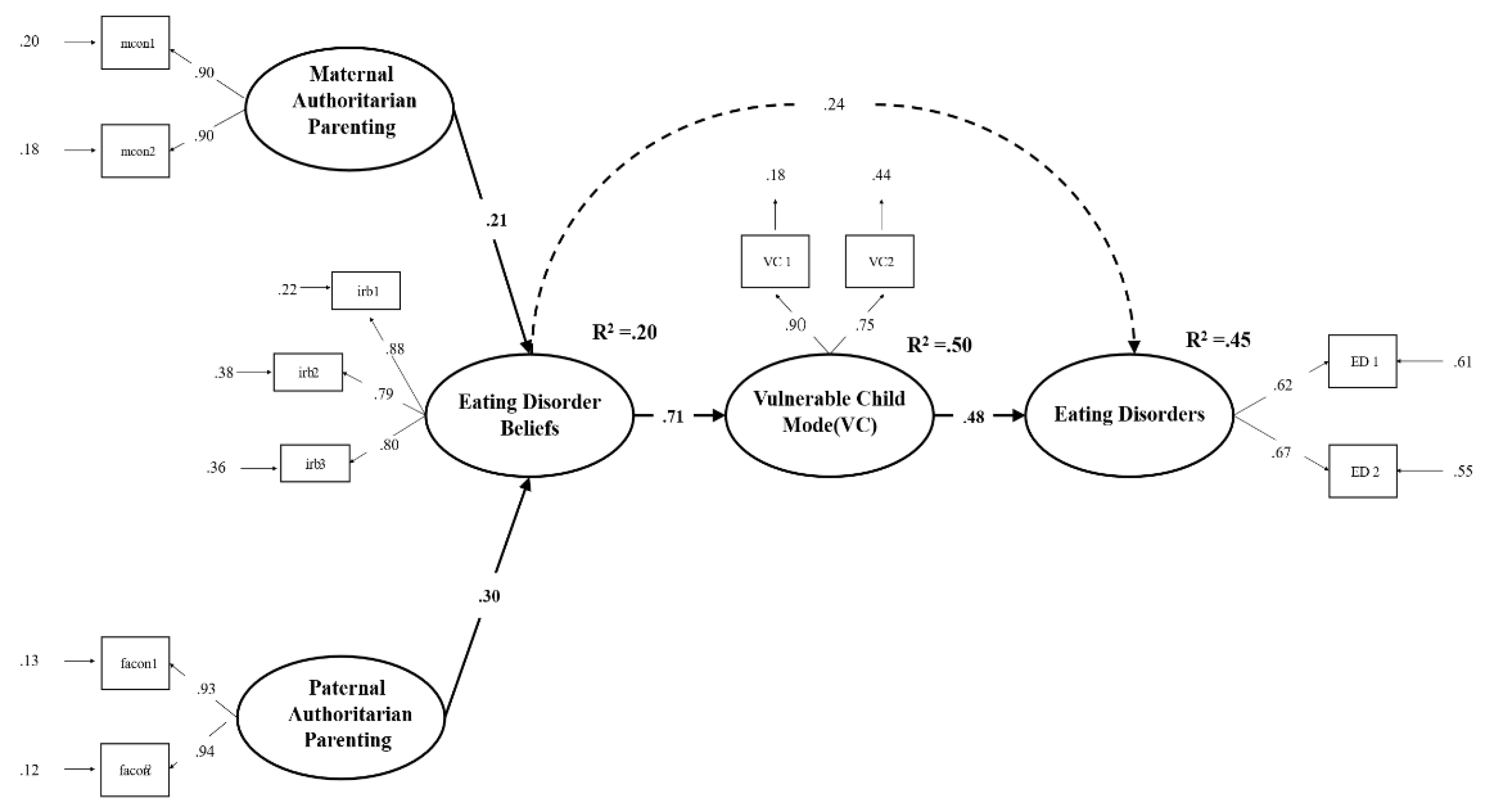

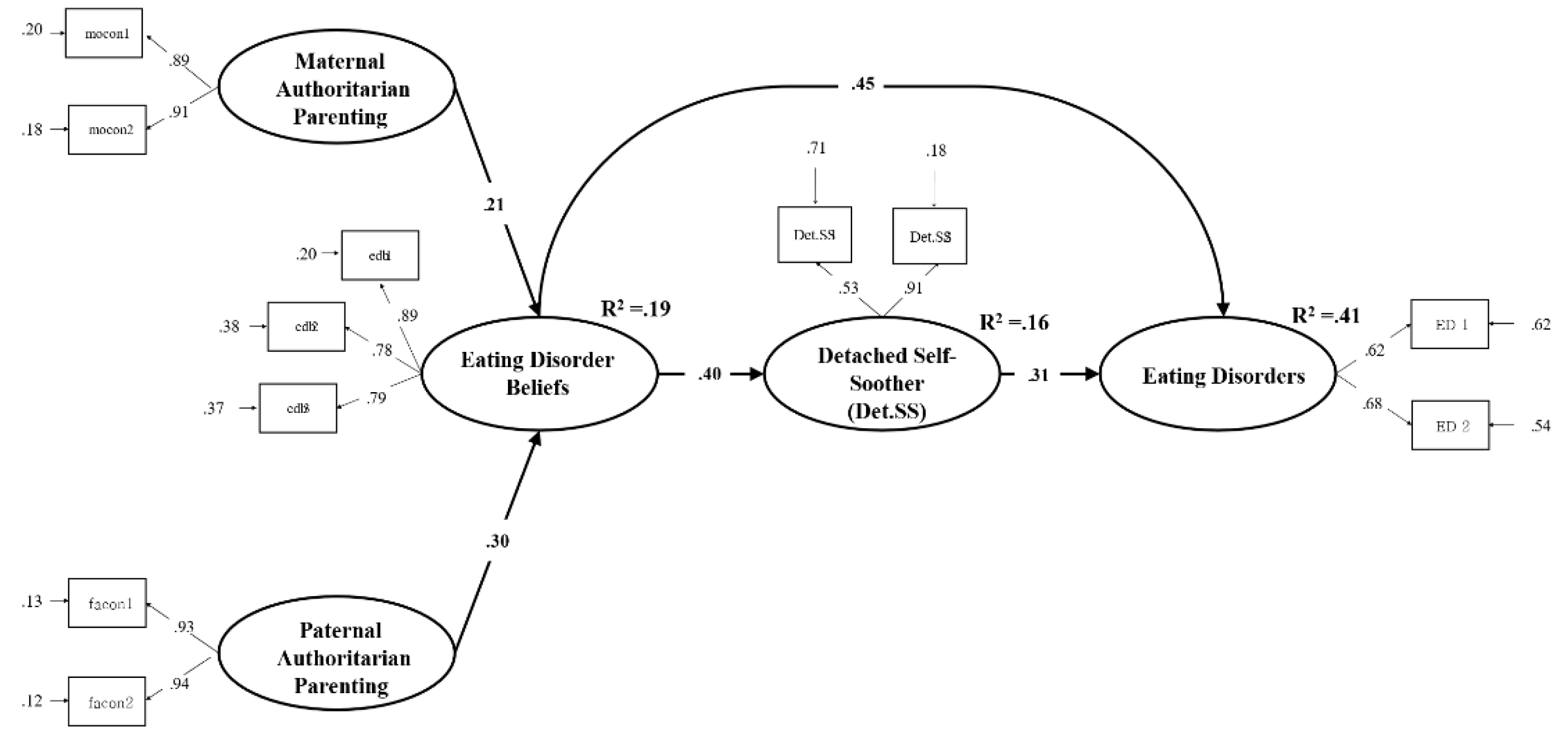

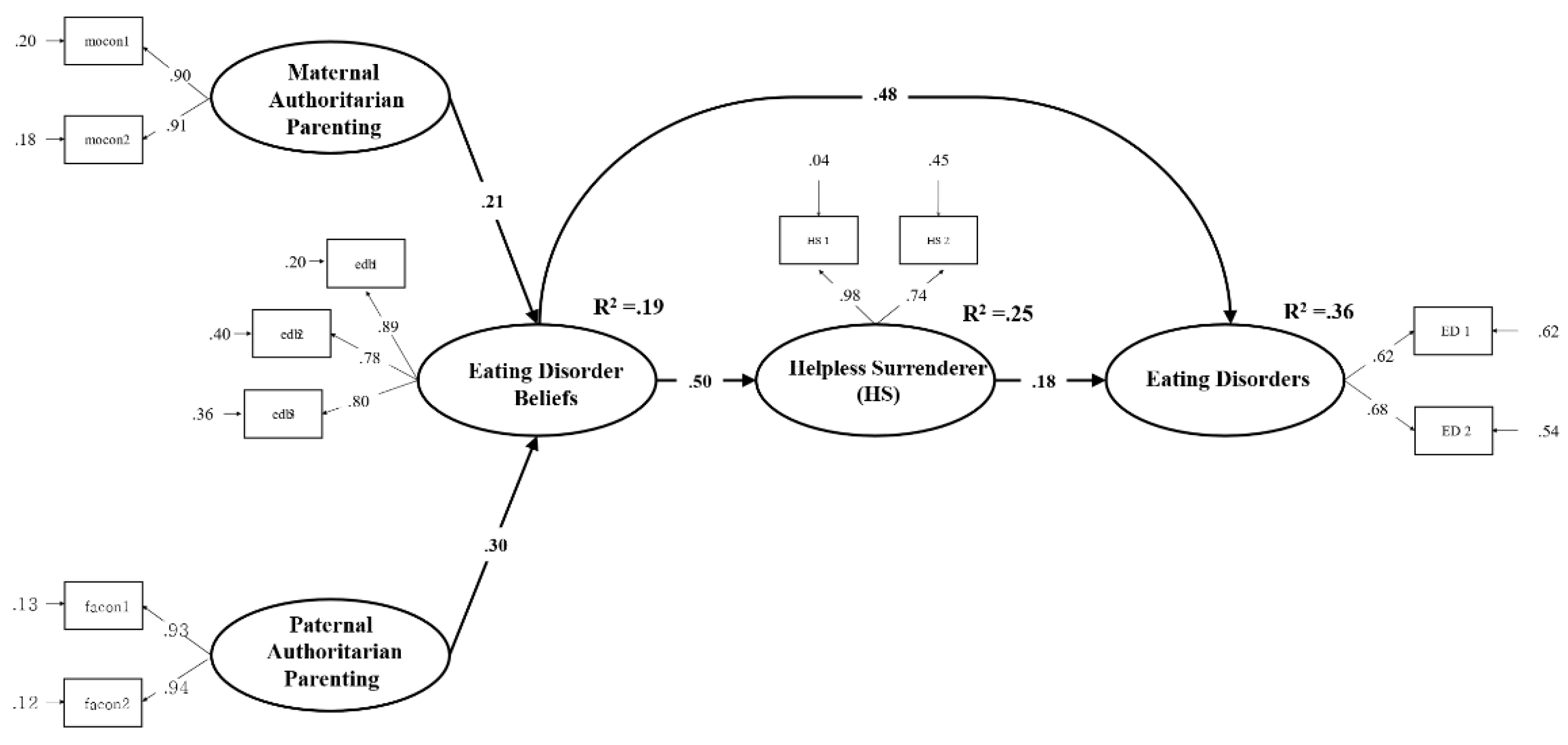

Second, we examined the dual mediating effects of eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes on the relationship between authoritarian maternal and paternal parenting and eating disorders. Only the vulnerable child, detached self-soother, helpless surrender, and eating disorder overcontroller mode pathways were significant.

Specifically, the results were as follows:

(1) The sequential mediation pathways of eating disorder beliefs and vulnerable child style were significant in the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders, suggesting that perceived maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors indirectly influence eating disorders through the sequential mediation pathways of eating disorder beliefs and vulnerable child mode. The finding that authoritarian parenting behavior and eating disorder beliefs only influenced eating disorders through the vulnerable child mode suggests the importance of the role of the vulnerable child mode in treating eating disorders. This finding supports schema therapy theory, which posits that maladaptive schema modes give rise to psychological disorders [

33]. The vulnerable child mode is associated with the early maladaptive schemas and is considered central to schema therapy because it provides the clearest expression of unmet needs and the resulting emotions. In patients with eating disorders, research suggests that providing corrective emotional experiences of unmet needs in childhood [

94], tending to the vulnerable child mode [

95], and creating supportive, authentic connections to help build healthy adult mode may be important in treating eating disorders. These schema therapy interventions are thought to lead to changes in eating disorder symptoms as well as changes in the unconditional core schema of eating disorders and changes in eating disorder beliefs, which are the core pathology of eating disorders. It is also expected that emotion-focused techniques, such as imagery rescripting, may be effective. Imagery rescripting can make trauma-related images more accessible, reorganize them to elicit new meanings [

96,

97], help clients recognize what they feel like to have their needs met [

98], and empower them to care for vulnerable children as healthy adults. Previous research has shown that imagery rescripting is an effective technique for reducing vulnerable child mode [

99] and has been shown to reduce eating disorders [

100,

101,

102].

(2) The dual mediation pathways of eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes (detached self-soother, helpless surrenderer, and disordered-overcontroller mode) were significant in the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders, that is, maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors indirectly influenced eating disorders through eating disorder beliefs, and eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes influenced eating disorders. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that negative parenting environments, such as authoritarian parenting behaviors, influence the formation of dysfunctional beliefs [

60]. In addition, the findings of the present study that eating disorder beliefs developed from authoritarian parental behaviors influence eating disorder symptoms through maladaptive schema modes provide empirical support for the etiology proposed in schema therapy. This supports Brown et al.

’s [

67] assertion that dysfunctional coping styles are a therapeutic focus for treating eating disorders, and suggests that a schema therapy approach may be a viable intervention to reduce eating disorder behaviors. In addition, the finding that eating disorder beliefs are important in the treatment of eating disorders supports the argument [

41,

103] that treating eating disorders requires an approach that considers both eating disorder beliefs and schema-level beliefs.

Focusing on maladaptive schema modes, the results were as follows:

(3) The dual mediation paths of eating disorder beliefs and detached self-soother mode were significant in the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders, that is, maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors indirectly influenced eating disorders through eating disorder beliefs, and eating disorder beliefs, and detached self-soother mode positively influenced eating disorders. This may mean that the use of avoidance coping modes, such as the detached self-soother mode, serves to comfort and block out uncomfortable feelings through eating disorder behaviors (e.g., binge eating and over-exercising). These findings are consistent with the Escape Model [

104] and research suggests that behaviors such as binge eating and compensatory behaviors are means of regulating negative emotions [

105]. Waller’s study ( as cited in [

106]) also viewed binge eating behavior as a secondary avoidance of negative emotions through the process of schematic avoidance. Addressing avoidance-coping modes, such as dissociated self-soothing, may be helpful in reducing eating disorder symptoms.

(4) In the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders, the dual mediation pathways of disordered eating beliefs and the helpless succumbent style were significant, that is, maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors indirectly influenced eating disorders through disordered eating beliefs and disordered eating beliefs and the helpless surrenderer mode positively influenced eating disorders. The helpless surrenderer mode is a newer style to describe eating disorders [

70,

71]), characterized by people in this mode expressing distress but not directly revealing true vulnerability, hoping that others will intuitively know their needs and acting as if help from others is not enough. In Marney, Reid, and Wright’s study [

107], individuals in this mode felt unable to change their behaviors, worried that others would not accept them if they recovered from their eating disorder, and wanted people to understand them without explanation, which may explain their hopelessness about their ability to change and poor response to treatment [

18].

(5) The dual mediating effects of eating disorder beliefs and eating disorder-overcontroller mode were significant in the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders, that is, maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors indirectly influenced eating disorders through eating disorder beliefs, and eating disorder beliefs and the eating disorder overcontroller mode had a positive effect on eating disorders. The eating disorder-overcontroller mode, like the helpless surrenderer mode, is an emerging mode for explaining eating disorders and is characterized by a focus on the “elevated feelings” that come from controlling the body and restricting basic human needs, distancing oneself from underlying feelings of vulnerability and distress [

70]. These findings share some similarities with the Emotion Avoidance Model [

108,

109] in terms of distancing from emotions and aligning with clinical perfectionism, as introduced by Fairburn et al. [

18]. Patients with eating disorders have been shown to share perfectionistic traits [

110,

111], and clinical perfectionism and weight/shape overvaluation often go hand in hand in that they operate in a system of self-evaluation: fear of failure (fear of overeating, being “fat,” and gaining weight), selective attention to performance (repetitive calorie counting, frequent body shape, and weight checks), and self-criticism arising from negatively biased evaluations of one’s own performance lead to aiming for and striving for high standards. This involves excessive effort to control eating, body shape, and weight, and this process is a factor in maintaining pathological eating behaviors. Therefore, it has been suggested that, in the case of patients with ED, a reduction in clinical perfectionism would facilitate change by removing the powerful networks that maintain eating disorders [

18]. In this regard, interventions in the eating disorder overcontroller mode may be a way to alleviate eating disorder behaviors and symptoms.

Third, we examined the mediating effects of maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behavior eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes to eating disorders, and found differences between mothers and fathers.

(1) Maternal and paternal differences were found in the dual mediating effects of maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors on the relationship between eating disorder beliefs and detached self-soother mode. Specifically, authoritarian maternal parenting behavior had a significant effect on the relationship between eating disorder beliefs and eating disorders through the full mediation pathway of eating disorder beliefs, but the dual mediation effect through the maladaptive schema mode (detached self-soother mode) was not significant. For fathers, both the full and dual mediation pathways of eating disorder beliefs were significant in the relationship between authoritarian parenting behavior and eating disorders.

(2) Maternal and paternal differences were found in the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors and eating disorders when examining the dual mediating effects of eating disorder beliefs and eating disorder overcontroller mode. Specifically, maternal authoritarian parenting behaviors had a significant effect on the relationship between eating disorder beliefs through the full mediation path of eating disorder beliefs, but a dual mediation effect through the maladaptive schema mode (eating disorder overcontroller mode) was not significant. For fathers, both the full and dual mediation pathways of disordered eating beliefs were significant in the relationship between authoritarian parenting behavior and eating disorders. This supports research suggesting that high paternal control leads to children’s inability to internally justify their own validity, which leads them to internalize unrealistic standards for themselves, leading to perfectionistic thoughts and behaviors [

112]. Additionally, children who feel unloved by their fathers may become more preoccupied with their own weight in an attempt to appear “perfect” in order to gain their father’s affection and attention [

113]. Authoritarian parenting is highly correlated with irrational perfectionism in children, consistent with findings that paternal authoritarian parenting behaviors, in particular, influence children’s perfectionism [

114].

Consistent with the results in (1) and (2), the findings of this study that fathers’ authoritarian parenting behaviors had a greater impact on eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes, such as avoidance and overcompensatory coping modes, suggest that fathers’ authoritarian parenting behaviors may have a more significant impact on their children. These results are partially consistent with Khosravi et al. [

115], who found that higher levels of authoritarian parenting behaviors in fathers and mothers are associated with greater use of avoidance and overcompensating coping styles. This is consistent with previous studies that have found that individuals with eating disorders tend to perceive their fathers’ parenting behaviors more negatively [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120]. In addition, these findings may be a result of differences in parenting styles, which may differ between mothers and fathers, depending on their roles [

121,

122,

123].

Fourth, we examined the dual mediating effects of eating disorder beliefs and helpless surrender mode on the relationship between maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting behavior and eating disorders, and found that the full mediation of eating disorder beliefs was significant. However, the effect of the dual mediation pathway of helpless surrenderer mode was not significant. This means that eating disorder beliefs developed from authoritarian parental behaviors have a stronger effect on eating disorders than the effect of eating disorder beliefs developed through the helpless surrender mode on eating disorders. Brown et al. [

67] also found a low correlation between the helpless surrender mode and eating disorders, which may be a factor in maintaining eating disorders rather than contributing directly to eating disorder behaviors [

107]. In addition, the helpless surrenderer mode is characterized by the hope that others will intuitively know their needs and act as if help from others is not enough, which is thought to interfere with forming authentic relationships with others. Fairburn et al. [

18] described interpersonal difficulties as a contributing factor to the maintenance of eating disorders, and it is thought that individuals in this mode are more likely to have the interpersonal difficulties described by Fairburn et al. [

18] than the eating disorder symptoms

Fifth, for modes that were not identified in this study, we found that

The child modes did not show a significant effect, except for the vulnerable child mode. These results are likely due to the differences in the types of eating disorders. Previous research has shown that groups with eating disorders show similar patterns of mode, but the angry and impulsive child modes were only significant in the bulimia nervosa group and not in the anorexia nervosa group, and not in the eating disorders and purging disorders. This may indicate that anger, loss of control, etc., are distinctive modes of bulimia nervosa [

43] and are consistent with previous research suggesting an association between bulimia nervosa and anger or impulsivity [

124,

125]. In addition, for other specified feeding and eating disorders, there was no association with the undisciplined child mode, suggesting that the role of the mode may differ across subtypes.

The dysfunctional critic mode is an internalized attribution of significant others [

126]. Dysfunctional critic modes are experienced primarily through thoughts and serve as a sense of identity [

55]. For people with eating disorders, controlling their weight and body shape is the only absolute value that they place on themselves. The lack of significant results is thought to be due to the fact that eating disorder beliefs function similarly to dysfunctional critic modes.

Among the maladaptive coping modes, self-aggrandizer and bully & attack were not significant, which is partially consistent with previous research [

43,

51]. Therefore, self-aggrandizer and bully & attack modes may be less prominent mechanisms in eating disorder pathology [

43]. In particular, bully & attack mode may be associated with antisocial personality disorder [

127,

128].

The implications of this study are as follows. First, it identifies the psychological mechanisms underlying eating disorders by examining the dual mediating effects of maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting on eating disorder beliefs and maladaptive schema modes in women in their 20s. Second, this study provides empirical support for and reaffirms the etiology of schema therapy.

The limitations of this study are as follows: First, out of the 16 modes, the mediating effect of the four maladaptive schema modes was significant. As there is little domestic or international research on maladaptive schema modes as a psychological mechanism for eating disorders, a replication study is warranted to understand the dual mediation pathways for the various maladaptive schema modes in this study. Second, the study population was limited to women in their 20s, limiting the generalizability of the results. In particular, the prevalence of eating disorders in males has increased in recent years. Therefore, future studies should include a wider range of age groups and sexes, including adolescents and men.