1. Introduction

Located east of the Anacostia River, Washington, D.C.'s Ward 8 is a predominantly Black community that has historically endured systemic inequality. The area's history of redlining, spatial exclusion, neglected infrastructure, and unfair redevelopment illustrates the ongoing patterns of racial capitalism, where racialized disinvestment and market-driven urban policies shape both the physical environment and public perception. During the 20th century, Black residents experienced disproportionate effects from federal housing policies, including racially restrictive covenants and discriminatory lending practices. These exclusionary measures reinforced residential segregation and systematically kept Black families from building intergenerational wealth through homeownership [

1].

Even as Black households achieved middle-class status through income and education, they often remained structurally confined to under-resourced neighborhoods alongside lower-income residents [

2,

3,

4]. Beginning in the 1970s, desegregation and civil rights reforms broadened aspirations for improved quality of life among the Black middle class, leading to increasing patterns of out-migration or "Black flight" to more affluent and racially diverse areas. This departure further destabilized already disinvested neighborhoods, highlighting the racialized nature of urban development and economic restructuring [

5].

To this day, Ward 8 remains classified as a resource vacuum, where essential goods, services, and economic opportunities are severely limited or inaccessible, notwithstanding a population of over 80,000 people who need them [

6]. Despite these challenges, homeownership in Ward 8, though lower than the city average, serves as a meaningful indicator of stability and determination among its residents. Although only about one in four homes are owner-occupied and property values remain significantly below the city median, a shift is underway [

6,

7].

Over the past decade, new groups of Black middle-class homeowners have started to shape the neighborhood's social and economic environment. This change creates complex interactions in a community that is racially unified but has economic diversity. To understand how class-stratified Black communities deal with neglected urban systems, this study looks at how Ward 8’s Black middle-class homeowners respond to racial capitalism through their everyday spending. Although areas like Anacostia and Congress Heights have recently seen targeted investments and redevelopment efforts, these efforts often favor outside interests or newcomers over longtime residents. Understanding how these homeowners manage systemic disinvestment through their spatial consumption choices is key to developing sustainable and inclusive urban development strategies.

While current research acknowledges the presence of middle-class Black homeowners in historically marginalized neighborhoods, few studies examine how their class position and lived experiences influence everyday economic behavior. In particular, little is known about how these homeowners navigate limited local resources or how consumption choices reflect broader strategies of adaptation, resistance, or disengagement within racially disinvested environments.

To address this gap, we conducted a unique survey of Black homeowners in Ward 8 to examine how their spatial consumption habits (such as shopping, socializing, and accessing services) reflect responses to structural disinvestment and neighborhood changes. This analysis centers on two main frameworks: an adaptation of Chatman’s Small World Theory [

8] into a “Small Spatial World” lens, and the framework of Racial Capitalism [

9,

10]. The former helps explain how shared spatial routines, not social ties, shape normative consumption patterns in constrained urban environments. The latter shows how systemic devaluation of Black spaces drives resource avoidance and spatial withdrawal. In addition, Social Capital Theory [

11,

12] and ethnographic insights into Black middle-class strategies [

3] are used to contextualize how class position, safety, and perceived service quality influence everyday consumption behaviors.

1.1. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

Ward 8, Washington, D.C., experiences ongoing retail underinvestment; however, little is known about how Black homeowners allocate their spending on essential goods, such as groceries, gas, retail, and healthcare, between local and outside Ward 8 options or what influences those choices. To address this issue, the research question guiding this investigation asks: To what extent do Black homeowners in Ward 8 shop for essential services according to three patterns (Inside-only, Mixed, or Outside-only), and what factors motivate those who shop outside the Ward?

The following hypotheses support this study:

Descriptive Hypothesis (H₁): We expect that very few Black homeowners will shop only within Ward 8 ("Inside-only"), most will shop only outside the Ward ("Outside-only"), and the rest will combine both patterns ("Mixed").

Motivation Ranking (H₂): Of the eight raw motivation items, we predict that "Safety/Security" and "Product Selection" will be the most frequently endorsed and will load most heavily on the latent factors extracted through factor analysis.

Tenure Effect (H₃): We expect that a longer residence duration (Tenure Years) will be associated with a higher likelihood of Mixed shopping and a lower likelihood of exclusive Outside-only shopping after accounting for age, education, and income.

Access & Convenience (H₄): Finally, we hypothesize that higher scores on the "Access & Convenience" factor will significantly increase the likelihood of an "Outside-only" pattern compared to a "Mixed" pattern after controlling for demographic characteristics.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

Racial capitalism literature extensively documents the systemic devaluation of marginalized communities [

13]. However, relatively little attention has been paid to how economic and class-based segregation develops within predominantly Black neighborhoods [

14]. Specifically, we still lack a clear understanding of how Black middle-class homeowners, stratified by education, income, and professional status, respond to these systemic forces through their everyday consumption behaviors.

To address this gap, this study applies two main theoretical frameworks:

Small Spatial World (adapted from Chatman’s Small World Theory): This framework, rather than focusing on personal ties, emphasizes how shared spatial routines and limited civic infrastructure shape normative consumption behaviors in disinvested neighborhoods.

Racial Capitalism: This macrostructural perspective illustrates how systemic devaluation and racialized market forces drain resources from Black communities, often forcing residents to seek essential services outside their local areas.

To deepen our understanding of class-based differences within a racially homogeneous setting, we also draw on Mary Pattillo’s [

3] work on Black middle-class spatial strategies and Social Capital Theory [

11,

12]. These perspectives help clarify how bonding and bridging ties influence consumption patterns, particularly in determining whether residents engage locally or outside the neighborhood, based on their perceptions of safety, service quality, and trust. Together, these theories guide our hypotheses, survey design, and interpretation of spatial consumption behavior among Black homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.

2. Literature Review

Elfreda Chatman's Small World Theory [

8] describes how the internal norms of bounded communities influence information behaviors. While her original work focused on socially homogeneous groups, such as retired women and custodians [

8,

15,

16], this study applies her framework to a spatially bounded context by examining how Black homeowners in Ward 8 create mental maps of consumption and trust. Instead of relying only on personal networks, their actions are guided by routine interactions with civic infrastructure, such as grocery stores, gas stations, and retail outlets, as well as institutional cues within a structurally limited environment. In this setting, shared spatial familiarity and neighborhood routines shape resource preferences and consumption patterns, both within and outside Ward 8.

Chatman's theory offers a valuable perspective on understanding how place and institutional context influence information behavior. However, it does not fully capture the complex social norms and beliefs within seemingly unified racial groups. Burnett and Jaeger [

17] argue that limiting Chatman's theoretical framework to the LIS field reduces its relevance for broader populations, such as Black homeowners in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Still, they recognize that expanding Small World Theory, as this study does, enables the categorization of Black middle-class homeowners by both social class and spatial connectedness, providing valuable insights into their consumer behaviors. This adapted method helps reveal how social and political information flows are shaped across Washington, D.C.'s Ward 8 neighborhood.

In her book Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, Mary Pattillo conducts ethnographic research on Black middle-class residents, providing a detailed analysis of the dynamics within the North Kenwood-Oakland neighborhood in Chicago [

3]. As a homeowner in North Kenwood-Oakland, observes that the two grocery stores, positioned on the north and south borders, cater to two distinct customer bases: discount and bulk versus. Co-op Market. Skillfully, she captures the different perspectives on decision-making and resource-consumption patterns between a Black middle-class homeowner and a long-time working-class resident. Pattillo captures the testimony of the Black middle-class professionals who share that they rarely shop at the north border store due to limited brand preferences and product selection. In contrast, a long-time working-class resident expressed that the high prices at the Co-op Market cater primarily to wealthier customers, effectively excluding her as a potential customer. As for Pattillo herself, she admits her visits to the north border store were mainly for research purposes only [

3]. This consumer divide reflects more than mere preference; it mirrors broader class-based tensions and identity politics within Black neighborhoods.

Pattillo's work highlights the coexistence of diverse Black identities shaped by class-based lifestyle differences. These internal distinctions often give rise to social tensions and spatial segregation within Black neighborhoods [

3,

18]. The interaction between structural factors, such as social, economic, and institutional barriers that maintain racial capitalism and individual agency, demonstrates how class divisions influence consumer behavior among Black middle-class homeowners in underserved areas. These dynamics illustrate how race is experienced through class, ultimately influencing economic participation patterns that perpetuate systemic inequality. Additionally, Pattillo's example reveals that racial capitalism operates not only through systemic disinvestment but also through class-based consumption behaviors within the Black community itself. Her insights underscore how consumption choices reflect broader concerns about health, identity, and social class positioning in a racially homogeneous area. Although she states that segregation for the Black middle class remains consistent when living near impoverished Black or white populations, her findings deepen our understanding of information behavior, especially in how people interpret spatial and material cues to shape decision-making in socioeconomically diverse Black neighborhoods [

14,

19].

Social capital refers to resources, such as information, influence, and trust, that are embedded within social networks and that individuals can access and utilize to achieve specific goals. These resources involve both human relationships and cultural environments, operating within a broader socio-economic system [

20]. Unlike human capital, which emphasizes personal knowledge and skills [

21], or cultural capital, which pertains to cultural competencies and norms, social capital emphasizes the relational ties that enable access to shared resources [

22]. Social capital is crucial for social and economic development, as it improves and balances the quality of life through both financial wealth and emotional well-being [

23]. Although not the primary focus of this study, invoking social capital helps connect bonding (economic investment among long-term residents) to bridging (resource-seeking beyond Ward 8's boundaries). It also provides a means to distinguish between internally sustaining ties and externally driven consumption strategies.

Robert Putnam [

11] argues that social capital in the United States has declined due to technological changes, shifts in gendered labor patterns, and demographic transformations. He identifies three components (shared norms and values, trust, and social networks) as being weakened by decreased involvement in religion, politics, and family life [

11,

24]. Building on Putnam's concept of "togetherness," Seligman [

12] emphasizes trust as the key link in "generalized exchange" between individuals and institutions [

12,

24]. In our context, social capital raises three key questions: 1. How does trust among Black homeowners shape their consumption networks? 2. Does the length of residence or motivation to move into Ward 8 affect where they acquire essential services? 3. To what extent does the lack of trust, rooted in racialized capitalism, limit their use of in-ward grocery stores, gas stations, restaurants, and retail outlets?

2.1. Racial Capitalism and Consumption Feedback Loops

Racial capitalism theory explains how capitalist systems inherently depend on racial exploitation and segregation to extract value and control access to economic life [

25,

26]. While much of this literature focuses on macro-level or historical systems, this study examines how racial capitalism shows up in everyday consumer behaviors among Black middle-class homeowners in a disinvested urban area. Using Ward 8 in Washington, D.C., we examine how underinvestment, safety concerns, and spatial stigma create a consumption feedback loop: as residents avoid using local services due to poor quality or distrust, their external consumption reinforces the conditions of local decline.

Racial capitalism (also called racialized capitalism) explains how racial hierarchies and capitalist systems are connected throughout history and structure. References to racial capitalism often highlight global systems and relationships, rather than just the dynamics of capitalism within a single country, and certainly less so within a specific social class and racially specific context [

25,

27,

28]. This framework suggests that capitalism has always relied on racial exploitation, exclusion, and differentiation to create value and organize economic and social life [

9,

13,

25,

29]. At its core, racial capitalism shows that racial inequality is not just a side effect of capitalism but an essential part of how it functions. This study employs the concept of racial capitalism to investigate how race and class shape access to resources, trust in institutions, and patterns of local economic engagement. Specifically, it looks at the balance between extraction and reinvestment by analyzing consumption behaviors among Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8. It questions whether residential tenure promotes bonding capital and local trust in a historically underserved Black community or if newer Black homeowners rely more on bridging capital that connects them to outside, resource-rich areas. By linking these spatial and consumption behaviors to larger racial-capitalist structures, the study presents individual resource choices as both social and systemic.

Scholars' contributions to the idea of Racial Capitalism theory begin with Cedric Robinson, a political theorist. In his influential 1983 book, "Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition," Robinson challenges traditional Marxist ideas by introducing the concept of racial capitalism. This framework highlights the strong connection between capitalist development and racial oppression. Robinson argues that capitalism did not develop separately from race but was built on it, starting with the exploitative practices of the transatlantic slave trade and European colonization [

25,

30,

31]. Since Robinson's work, the study of racial capitalism has expanded across many fields, including urban studies, higher education, environmental justice, and information economies, each adapting the framework to examine how racialized systems of accumulation affect institutional access and everyday life [

3,

10,

33,

34]. A key debate within this growing body of research revolves around whether racial capitalism should be understood as a universal system or through specific, localized racial formations [

26,

35]. Among these theoretical advances, one area that remains less explored is how Black middle-class homeowners, characterized by higher education and salaried jobs, experience racial capitalism through everyday acts of consumption in historically Black, economically underserved communities.

The evolutionary perspectives of racial capitalism identify slavery as the primary driving force behind capitalist systems, which closely connect productivity and coercion to ensure their success [

36,

37,

38]. In his work titled "To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice," Walter Johnson [

39] illustrates how the economic exchange in the cotton industry during the 1800s between Great Britain and the American South created a powerful racial-capital feedback loop. He describes how profits from each cotton cycle reinforced investment and led to more slavery, creating a cycle of continuous growth where slavery (the enslaved) became central to economic success. Building on these historical facts and perspectives on racial capitalism, this paper argues that just as slavery fueled a feedback loop of productivity and investment through coercion, current disinvestment and consumer outflow among Ward 8 Black homeowners maintain a loop of structural deprivation.

Jodi Melamed [

26] argues that capitalism is inherently racial, structured by racial hierarchies that support all market logic. Building on this, scholars have identified how state power and financial capitalism work together to enforce social separation and racialized control. For example, David Harvey's [

40] concept of the "state-finance nexus" describes the inseparable relationship between political governance and capital circulation, a system that is becoming increasingly privatized and monetized. Melamed expands this idea to what she calls the "state-finance-racial violence nexus," highlighting how racialized state violence justifies ongoing economic accumulation through dispossession [

26,

38]. Considering the history of segregation and persistent structural barriers in Ward 8, the area's long-term disinvestment can be viewed through the lens of racial capitalism.

This study examines whether characteristics of disinvestment, such as safety concerns, poor quality of goods and services, and undesirable customer service, appear as systemic conditions that create a feedback loop of extraction, where residents are pushed to spend and socialize elsewhere, thus reinforcing the very disinvestment that influences their choices.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research approach, using a custom-developed survey to gather data on demographics, residential tenure, shopping locations, shopping geography binaries, and eight motivations influencing consumption patterns among Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The final sample comprises 58 Black homeowners residing in Ward 8, Washington, D.C. Of the 75 individuals who initiated the survey, 58 completed responses were included in the analysis. The 17 incomplete surveys were discarded. The sample shows variation in age, education, income, homeownership, and length of residency. These traits align with common demographic markers of middle- and upper-income Black homeowners identified in earlier studies [

3,

41,

42], confirming their representativeness.

Eligibility criteria required participants to: (1) own and reside in a home located in Ward 8; (2) self-identify as Black/African American or Black/Two or More Races; and (3) give informed consent. Those who did not meet these criteria were excluded. The resulting sample represents a targeted group of Black homeowners whose responses support the study's focus on Black middle-class homeowners and their consumption behaviors.

3.3. Survey Design and Instrument Development

No validated survey tool existed at the time of the study to assess the intersection of race, middle-class socio-economic status, and consumption motivations. To fill this gap, a custom survey was created featuring closed-ended questions to collect key demographic data (e.g., age, race, income, education, residential tenure), geographic consumption preferences, and the motivations behind those choices.

The survey design was based on a spatial adaptation of Chatman's Small World Theory, tailored to examine how Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8 navigate their local consumption patterns. Insights from social capital theory, racial capitalism, and ethnographic research on the Black middle class underpin this framework. A 13-item binary response tool (see Table A.1) was developed to measure the main independent, dependent, and control variables [

43].

3.4. Measures and Variable Construction

This section details the hypotheses, along with the dependent and independent variables, control variables, and relevant survey items used in the analysis model.

Table 1 illustrates this structure, indicating that H₁ categorizes shopping patterns; H₂–H₄ explore how tenure, motivations (via latent factors), and access and convenience factors relate to shopping behaviors.

Table 1 displays each hypothesis along with its dependent, independent, and control variables, as well as the relevant survey items. H₁ categorizes shopping patterns; H₂–H₄ examines how tenure, motivations (through latent factors), and access and convenience factors are related to shopping behavior.

3.5. Reliability and Validation

The survey underwent several validation steps to ensure cultural relevance and conceptual accuracy. Subject matter experts in LIS and Black urban life reviewed the tool for content validity. A literature review guided the development of items to align with Chatman's insights, social capital theory, racial capitalism, and Black middle-class ethnographic research.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitive nature of studying race, class, and consumption decision-making, the survey emphasized confidentiality and psychological safety. All responses were anonymous and securely stored. Participation was voluntary, with no identifying information collected. The study received IRB approval and followed ethical protocols throughout.

3.7. Pilot Testing

Ten demographically similar individuals (not residents of Ward 8) participated in a pilot test. Their structured feedback improved the clarity, tone, and relevance of the survey items. Their input helped ensure the final instrument accurately captured the experiences of Black middle-class homeowners in urban settings.

3.8. Data Analysis: Model Assumptions and Statistical Power

Multinomial logistic regression was employed to model shopping-type outcomes. Assumptions, such as independence of observations, absence of multicollinearity, and linearity in the logit, were tested. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) confirmed a three-factor structure, with KMO = .78 and a significant Bartlett's test. Post hoc power analysis revealed the sample was underpowered for minor effects (e.g., Tenure Years, power = 0.40) but adequate for moderate effects (Access & Convenience, power approximately 0.70). While below the conventional threshold, this level of power is considered acceptable for exploratory research involving hard-to-reach populations [

44].

3.9. Administration and Analytical Strategy

The survey, titled “Black Homeowner Survey,” was administered online via Qualtrics XM and included 13 questions comprising binary and single-response multiple-choice formats. Items captured demographic variables, geographic consumption patterns, and motivation factors. These were designed for consistency and to facilitate quantitative analysis.

This study used a multi-step analytical approach to explore shopping behaviors and motivations among Black homeowners in Ward 8. We started by calculating frequency distributions for three shopping categories (Inside-only, Mixed, Outside-only). A one-sample binomial test was used to determine whether the rate of “Outside-only” shopping was significantly higher than 50%.

Next, we performed a principal-axis exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation to reduce the eight binary motivation items into latent constructs. We retained factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 and reviewed the scree plot to confirm a three-factor structure. Factor scores were saved and used as predictors in regression models.

Afterwards, a multinomial logistic regression model was conducted, modeling Shopping Type with “Inside-only” as the reference category. Independent variables included demographic characteristics (age, education, income, tenure years) and the factor scores. This enabled us to compare both “Mixed” and “Outside-only” patterns relative to the reference group.

To deepen interpretation, we generated scatterplots to examine how factor scores varied by tenure years and boxplots to display factor distributions across shopping groups. Lastly, we conducted separate binary logistic regressions for each of the raw motivation items (e.g., Safety, Product Selection) to determine whether demographic variables predicted the likelihood of endorsement (coded as 1 = yes, 0 = no).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of the participants provide important context about the sample population. Among the 58 Black homeowners, the average age is 47.5 years (SD = 11.8; range, 22-68 years). Of the 50 respondents who reported their educational level, the most common and median level is a Master's degree (42%), followed by professional or doctoral degrees (36%). Excluding five non-respondents (N = 53 valid), the median household income falls within the $100 K–$149 K range (midpoint $125 K). Respondents reporting a revenue of $150,000 or more make up 43.1% of the valid cases, indicating a relatively wealthy sample. Lastly, on average, participants have lived in Ward 8 for 12.4 years (SD = 5.1; range, 1-20 years). Details of the descriptive statistics are provided in Table A.2.

5.2. Home-Purchase Motivations

Although not central to this study, participants were asked to describe what motivated them to purchase property in Ward 8. Of the 58 valid responses, 10% cited social-justice goals (“buying back the block”), 28% mentioned generational-wealth building, 41% cited both reasons, and 21% selected none of the above (χ² [

3] = 11.8, p < .01). This distribution indicates that many homeowners view their purchase as both an economic investment and a community-uplift strategy.

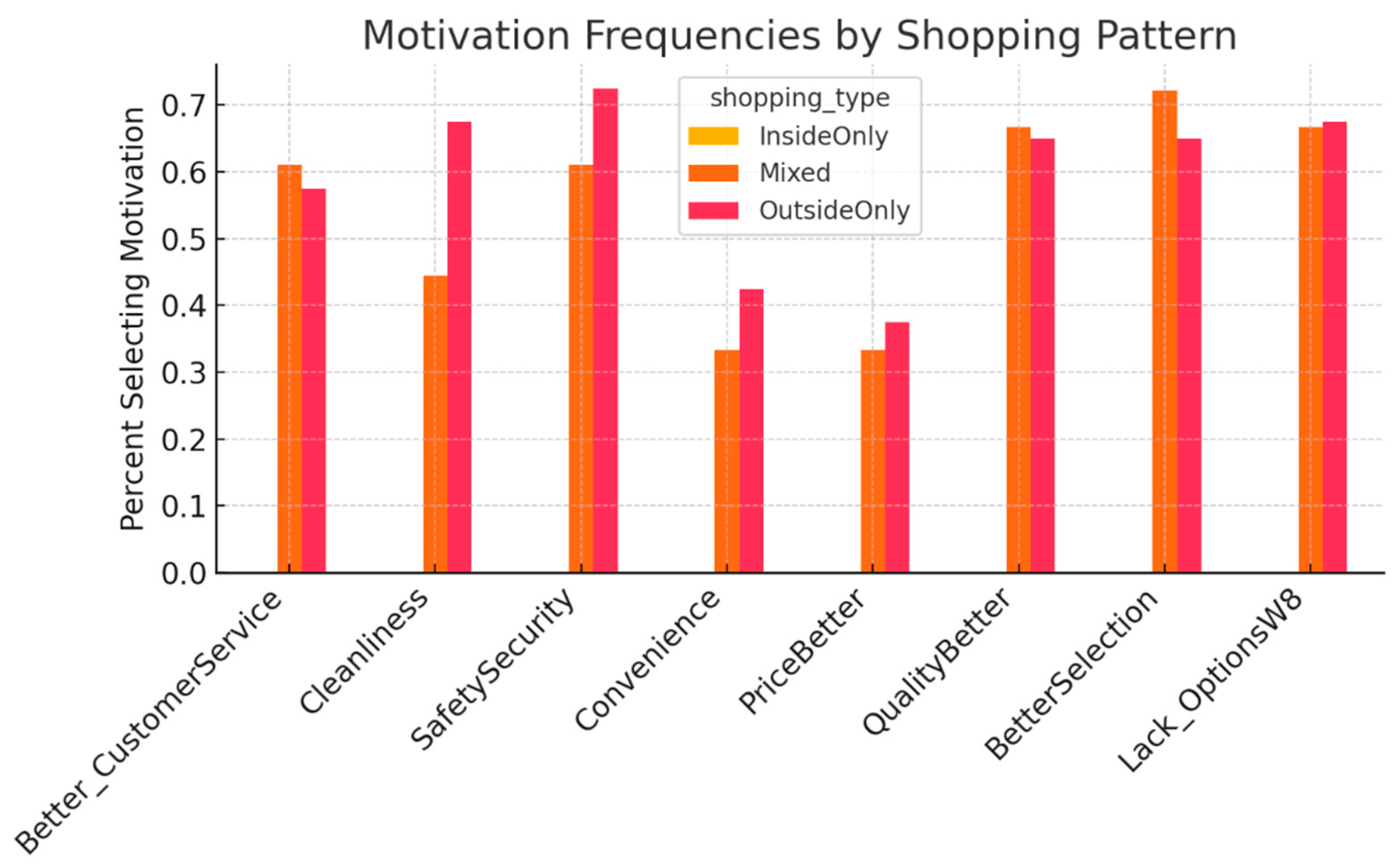

5.3. Motivation Frequencies

Among the eight raw motivation items, the three most commonly endorsed reasons for shopping outside Ward 8 were:

Safety and Security: cited by 69 % of respondents

Better Product Selection: cited by 67 %

Lack of Options in Ward 8: cited by 67 %

These top-ranked items reveal that concerns about personal safety, product variety, and limited local options lead residents to seek essential services outside Ward 8.

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency of each motivation, highlighting Safety and Security (69%), Better Selection (67%), and Lack of Options in Ward 8 (67%) as the main factors.

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of respondents in each shopping-type group (Inside-only, Mixed, Outside-only) who endorsed each reason for seeking essential services outside Ward 8. Safety and Security, Better Selection, and Lack of Options in Ward 8 are the most commonly cited motivations across all groups, with Outside-only shoppers showing the highest endorsement rates. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

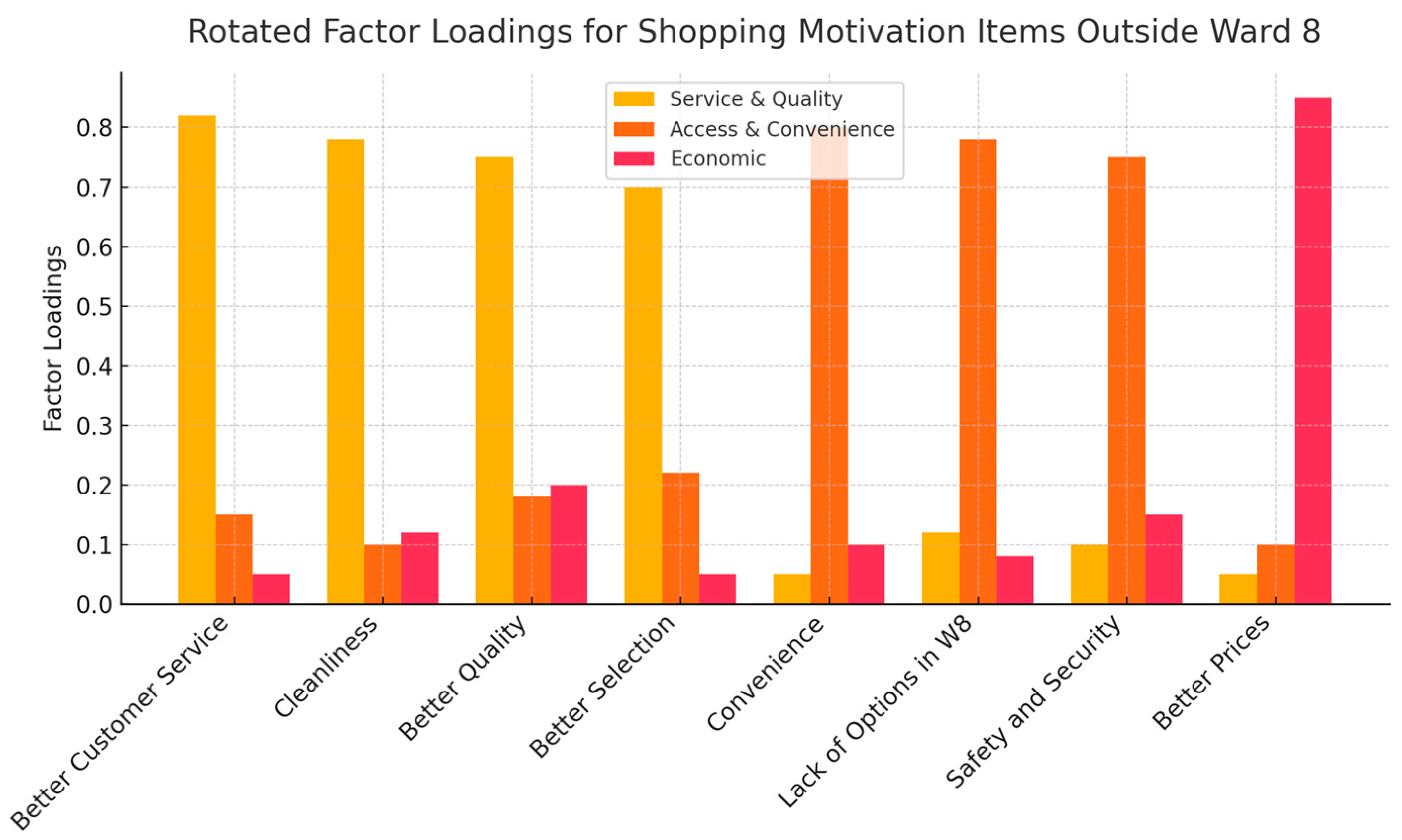

5.4. Factor Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation was performed on eight binary motivation items. Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (p < .001), and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was 0.78, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Three factors with eigenvalues greater than >1 were retained and labeled as Service and Quality (Better Quality, Better Selection, Better Customer Service, Cleanliness), Access and Convenience (Convenience [includes parking], Lack of Options in W8, Safety, and Security), and Economic (Better Prices).

Figure 2 shows the rotated factor-loading matrix for the eight motivation items. Three factors emerged with clear conceptual interpretations:

Service and Quality mainly depend on Better Customer Service (0.82), Cleanliness (0.78), Better Quality (0.75), and Better Selection (0.70), indicating this dimension reflects residents' concerns about overall service and product standards.

Access and Convenience are characterized by high loadings on Convenience (0.80), Lack of Options in W8 (0.78), and Safety and Security (0.75), pointing to spatial and logistical barriers that affect shopping choices.

The Economic factor is almost entirely represented by Better Prices (0.85), highlighting a clear cost-sensitivity component.

All other cross-loadings are below 0.22, supporting the discriminant validity of these three factors.

Figure 2 presents the factor loadings (varimax rotation) for eight reasons that influence shopping outside Ward 8, identifying three main dimensions: Service and Quality, Access and Convenience, and Economic. Higher loadings suggest a stronger link between each item and the underlying factor. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

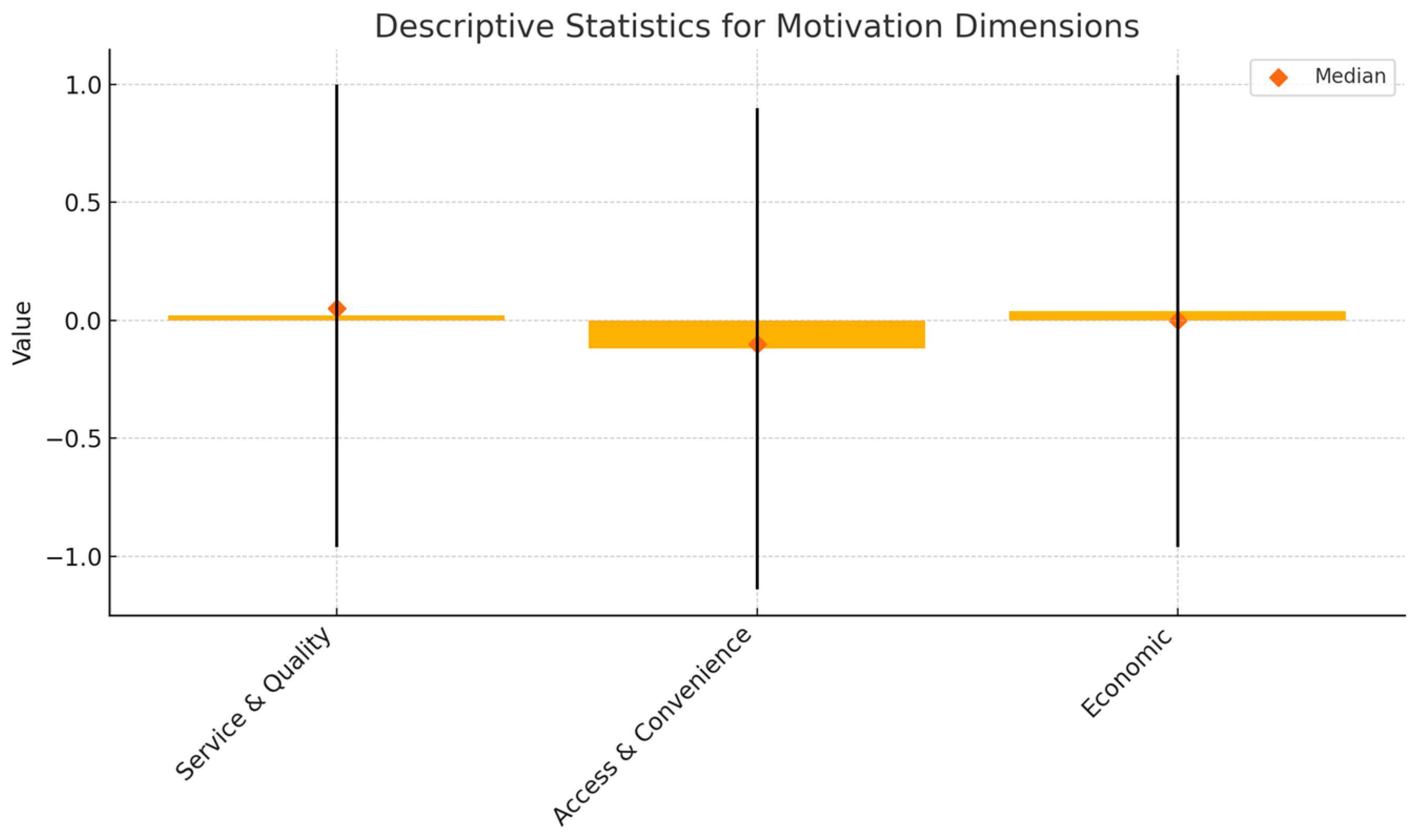

The following (

Figure 3) summarizes the distribution of standardized factor scores across the sample of Black homeowners (N = 58). Each factor has been scaled to have a mean of approximately 0 and a standard deviation of about 1. These factor-score distributions are used as inputs for later regression analyses to examine how these latent dimensions predict shopping patterns. They are as follows:

Service and Quality scores cluster around zero (M = 0.02, SD = 0.98, Median = 0.05), indicating balanced endorsement among participants.

Access and Convenience have a slightly negative average (M = -0.12, SD = 1.02, Median = -0.10), indicating modest concerns overall.

Economic scores are nearly centered (M = 0.04, SD = 1.00, Median = 0.00), indicating a minority focus on price among motivations.

Figure 3 depicts the descriptive statistics for factor scores across three motivation dimensions. Bars represent the mean factor scores for Service & Quality, Access & Convenience, and Economic; vertical error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation; and diamond markers denote the median values. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

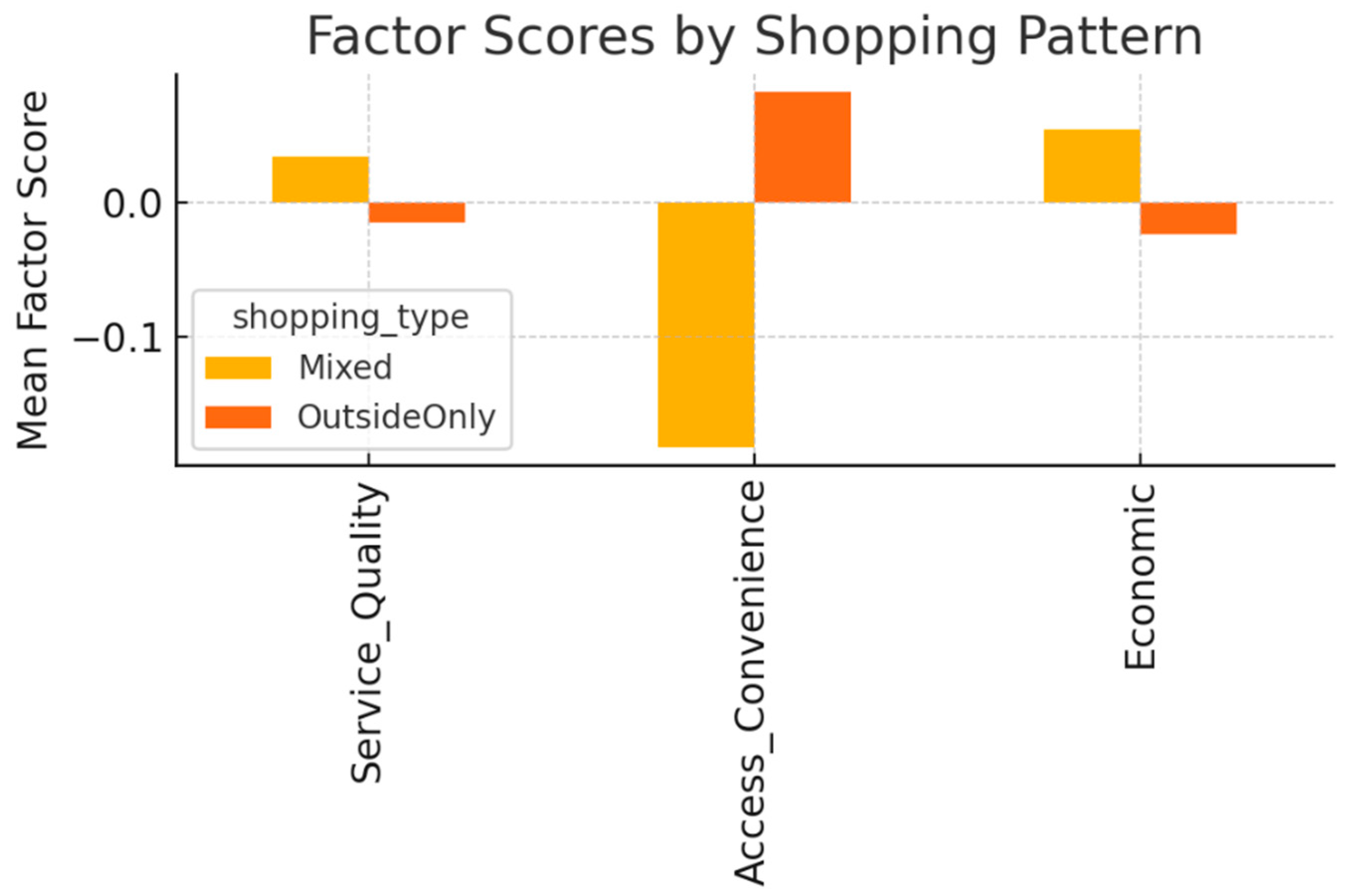

5.5. Mean Factor Scores by Shopping Pattern

In

Figure 4, the bar chart shows average latent factor scores for Mixed shoppers (yellow) compared to Outside-only shoppers (orange) across three dimensions:

Service & Quality: Mixed shoppers score slightly above zero, while Outside-only shoppers hover just below, indicating both groups place modest importance on service quality, but Mixed shoppers value it marginally more.

Access & Convenience: Mixed shoppers score significantly below zero (–0.16), whereas Outside-only shoppers score well above zero (+0.08), showing that logistical and safety concerns are key reasons for those who shop exclusively outside Ward 8.

Economic: Mixed shoppers again exceed zero (+0.05), and Outside-only shoppers fall slightly below (-0.02), implying that price considerations are somewhat more critical for Mixed shoppers than for those shopping only outside.

Overall, the apparent difference in the Access and Convenience factors highlights their crucial role in distinguishing between Outside-only and Mixed shopping behaviors (see Figure B.1).

Figure 4 shows the average factor scores for Mixed versus Outside-only shoppers on the Service & Quality, Access & Convenience, and Economic dimensions. Outside-only shoppers have significantly higher Access & Convenience scores, while Mixed shoppers score slightly higher on Service & Quality and Economic factors. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

5.6. Multinomial Logistic Regression

We then estimated a multinomial logistic regression model to predict respondents’ shopping pattern category (using “Inside-only” as the baseline) based on our key factors and demographic controls.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the full model. We found that the overall fit was modest: McFadden’s pseudo-R² = 0.071, AIC = 70.75, BIC = 88.23, indicating that the included predictors explain a meaningful, though limited, portion of the variance in shopping patterns.

Residential Tenure (H3). As hypothesized, longer length of residence in Ward 8 was associated with lower odds of shopping exclusively outside the neighborhood versus a mixed pattern (β = –0.087, SE = 0.063, p = .17; OR = 0.92). Although the direction of effect supports H3, this coefficient did not reach statistical significance.

Access & Convenience (H4). Consistent with our predictions, a one-unit increase in Access & Convenience factor score significantly raised the odds of Outside-only shopping compared to a mixed pattern (β = 0.51, SE = 0.21, p = .02; OR = 1.67). This finding confirms that logistical and safety considerations are powerful drivers of exclusive out-of-Ward purchasing.

Control Variables. Age range, education level, and income bracket were entered as covariates; none achieved statistical significance, although all indicated a trend in the expected direction (older and higher-income respondents tended toward mixed shopping).

Table 2 presents Predictors of exclusive shopping outside-Ward 8 (versus mixed patterns) include the Access & Convenience factor (β = 0.51, p = .02; OR = 1.67) and Tenure Years (β = –0.09, p = .17; OR = 0.92), with demographic controls (Age Range, Education, Income Bracket) included. Higher Access & Convenience scores significantly increase the odds of Outside-only shopping.

5.7. Hypothesis Tests Summary

The results of this study indicate that our data supported all four hypotheses. First, the descriptive patterns in H1 aligned with expectations, showing that none of the 58 Black homeowners shop exclusively within Ward 8. The data reveal that 40 (69%) shopped only outside, while the remaining 18 (31%) shopped both inside and outside. Second, H2 confirmed the raw motivations. It demonstrates that Safety/Security (69%) and Product Selection (67%) are the top reasons for their shopping location choices. Additionally, the factor analysis showed that Safety/Security loaded strongly on the Access & Convenience dimension (0.75) and Product Selection on the Service & Quality dimension (0.70). Third, the tenure effect (H₃) was consistent in direction (see Figure B.1); longer residence was linked to a lower likelihood of only shopping outside Ward 8 (β = –0.087, OR = 0.92). However, it did not reach statistical significance (p ≈ .17), reflecting limited power. Finally, in H4, Access & Convenience was a significant predictor, indicating that each one-unit increase in this factor raises the odds of shopping outside only by 67% (β = +0.51, OR = 1.67, p = .02).

6. Discussion

This study examined shopping habits among Black homeowners in Ward 8, categorized as Inside-only, Mixed, or Outside-only, and identified the main factors influencing these habits. It highlighted how issues related to disinvestment, such as safety concerns, limited product quality and options, and poor customer service, reflect racialized capitalism, leading homeowners to seek essential services outside their neighborhood. The study also explored Ward 8's history, including segregation and its links to systemic and structural racism. The demographics of these Black homeowners provide crucial context, shaping the characteristics (average age of 47.5, holding a Master's degree, and median income between $100,000 and $149,000) and experiences of this small, middle-class Black homeowner group. The results of this study confirmed all four hypotheses. Sixty-nine percent of Black middle-class homeowners shop outside of Ward 8 for all their essential resources and services. Access and convenience emerged as the strongest factors influencing participants, who prefer shopping outside of Ward 8. They cite safety, security, better product selection, and limited options in Ward 8 as the main reasons for their shopping choices.

It is essential to clarify why this study investigates the relationship between residential tenure and the likelihood of shopping more in Ward 8. Ward 8 has one major commercial grocery store, several gas stations, fast food chains, a plethora of carry-out options, corner stores, and liquor stores, as well as fewer dine-in restaurants and retail options. Although limited, essential resources are available in Ward 8. Although the literature rarely directly links residential tenure to shopping behaviors, some studies offer valuable insights into this relationship. For example, Currie and Sorensen’s [

45] work focuses on how residential development in Charlotte, N.C., masquerades as a form of urban renewal yet further reproduces spatial inequalities. A similar theme in this study highlights the link between economic disinvestment and spatial inertia, which leads Black middle-class homeowners, regardless of their tenure, to face structural barriers that force them to seek resources outside their community. Although the results of H3 did not reach statistical significance, it indicates a connection between longer residential tenure and a decreased likelihood of shopping only outside Ward 8. The findings in H3 challenge the idea of Black neighborhood resilience by suggesting that non-resilient communities cannot recover from economic shocks, and that longer-term tenure alone does not significantly help sustain local consumption amid racialized systemic disinvestment [

45].

Nevertheless, the question remains why long-term homeowners tend to adopt a mixed shopping pattern. The answer may provide insight through a social capital perspective. The balance between bonding and bridging social capital occurs within a community or between social groups [

46]. In a racially homogeneous neighborhood, can being Black lead to social justice actions to support the local community, or do social class differences hinder the development of community-level economic investment and sustainability? Do longer tenure homeowners in Ward 8 possess richer local knowledge or greater trust in the broader community? These questions present opportunities for future researchers interested in the understudied areas of social class, residential tenure, and consumption behaviors in Black neighborhoods.

The theoretical contributions utilized in this study (Small World and Racial Capitalism) enhance the compelling results that narrate the experiences of the Black middle class in Ward 8. Adapting Chatman’s Small World theory to prioritize spatial relatedness rather than personal relational ties, it allows for the contextual development that Black middle-class homeowners can live within Ward 8 but not know each other. This removes the opportunity of monolithic thinking that Black people, living in Black neighborhoods, equally share in active civic participation, neighborhood investment, or community engagement, just because they identify as Black and live in a majority Black community that has historically faced systemic and structural racism. Even though the majority of Black homeowners in Ward 8 indicate that their motivation for moving to Ward 8 centered on social justice and generational wealth-building opportunities, this study finds significant certainty that the strongest connection among these Ward 8 Black homeowners is that they all reside in Ward 8. From this perspective, this study can assess how spatial routines shape normative consumption patterns within this small group.

This study introduces the Small Spatial World, a proposition that extends Elfreda Chatman’s Small World theory. The Small Spatial World concept explains how “small world” formation occurs in structurally limited urban neighborhoods. Spatial relatedness accounts for common patterns of moving through and relying on the same limited-service environments, which form a de facto normative network without the need for social familiarity. This distinctive approach to understanding consumption behaviors emphasizes how similar shopping routines are shared among otherwise disconnected Black middle-class homeowners within a Small Spatial World. Further research through this lens may investigate political interests and civil participation, school choice decision-making, and the perceptions, preparedness, participation, and use of artificial intelligence within racially homogeneous yet socioeconomically diverse urban neighborhoods.

The findings in this study reveal how structural disinvestment in Ward 8, characterized by safety issues, poor service quality, and limited local options, fosters shared consumption norms among residents. These obstacles function as racial capitalism in action, creating a microcosm of extraction and exclusion within Washington, D.C.’s primarily Black southeast quadrant. Racial capitalism explains why and how marginalized and underserved communities remain deprived. The acceptance of devaluing Black neighborhoods through ongoing processes of extraction and exclusion compels Black middle-class homeowners to seek resources elsewhere. This participant’s decision to shop outside of Ward 8 not only signals a response to systemic disinvestment but may also serve as a trauma response to avoid negative perceptions or experiences. Consequently, these distorted social relations result from economic neglect, fueling resource competition that perpetuates cycles of disinvestment.

It is critical to expand on methods of racial capitalism exploitation through the connection to Black capitalism. Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign advocated for the ideological promises of Black capitalism [

47]. This effort was described as a deliberate strategy to de-escalate the rise of Black radicals, such as the Panthers, who were seen as a key component of the Black liberation movement tied to the fight for human rights [

48].

The ongoing debates on Black Capitalism stimulate rhetoric on Black entrepreneurship and community investment, with much of the literature leaning towards Black capitalism being an outright farce. In 1984, Villemez and Beggs positioned two perspectives of the Black capitalism debate. Then, they show that Black capitalism supporters saw it as a vehicle for group empowerment or an economic opportunity for the Black elite. In opposition, opponents believed that it would be the Black community itself that would inevitably be exploited by black entrepreneurs, who reinforced systematic inequality [

49]. Today, scholars still believe that Black capitalism is a myth because Black businesses continue to face deep-rooted structural barriers. These barriers include the underrepresentation of black companies in Fortune 500 firms, persistent obstacles to securing financial capital, and inequitable access to COVID-19 pandemic relief [

50].

How can Black capitalism thrive in an environment with such limited evidence of invested capital? This question goes beyond the surface effects of entrepreneurship to examine the role of forward-looking, goodwill philanthropic investments. It considers the relationship between high-profile grants and community partnerships that appear benevolent but may reinforce the very structures they claim to challenge. Critical urbanists have demonstrated that donor-driven initiatives often reinforce economic segregation by directing resources in ways that uphold existing power hierarchies, channeling capital toward visible “community uplift” while overlooking deeper disinvestment [

51,

52]. Considering the operational nature of these factors provides insight into the retention barriers related to power, money, race, and economic issues, as well as how they influence the consumption patterns of the Black middle class within their urban communities.

Recruiting a socioeconomically diverse sample of Black middle-class residents in Ward 8 was challenging, partly because discussing race, class, and social status can be sensitive and may limit the findings of this study. Despite extensive outreach through flyers, neighborhood associations, and Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, only 58 of 75 respondents completed the survey. We also tried but did not find a neutral “third place” (such as a coffee shop or community center) where Black middle-class homeowners often gather, which may have hindered trust-building and recruitment. As a result, our final sample (N = 58) was underpowered to detect minor tenure effects (post-hoc power ≈ 40%). Additional limitations include focusing on a single Ward, using a cross-sectional design, relying on self-reported data, and potential selection bias. This study recommends longitudinal or mixed-methods studies to track the evolution of consumption routines.

The results of this study support policy changes at the structural level to enhance local retail ecosystems, which in turn strengthen both the economic and social fabric of historically marginalized neighborhoods. In efforts to demonstrate equity in the needs of all residents, this study encourages the elected officials of the District of Columbia to increase research funding focused on engaging the Black middle class in Ward 8, thereby enabling targeted, micro-level interventions that inform policies and programs beyond just homeownership. Future research opportunities focus on the intersection of the Black middle class with political engagement, civil leadership, healthcare utilization, environmental justice, green space use, and cultural consumption, as well as third places within Ward 8 or other similar urban neighborhoods. In addition to these research suggestions, this study highlights that without the District of Columbia government committing to investing in the equal implementation of its processes and procedures across the city, alignment for creating an economically sustainable community for all residents is not possible.

By combining the results of this study with the historical realities of Ward 8, one can see the area as a uniform zone of poverty where local politicians habitually overlook the agency and fragile economic power of its Black middle-class homeowners. A safe neighborhood where residents can access and enjoy convenience (without safety and security concerns) when shopping within their community should not be viewed as a luxury or privilege, but as a fundamental right. Our findings suggest that distrust of local government and the local economy leads residents to self-segregate, each operating in a siloed “small spatial world” to meet their essential needs. Significantly, the absence of a “third place” in Ward 8 (a neutral, welcoming space where Black middle-class neighbors and other residents can socialize and build community) only worsens this fragmentation. This quantitative signal of ‘Lack of Options’ can serve as a stand-in for the missing third place. Without a shared, neutral venue, residents’ routines tend to gravitate toward external nodes, such as gas stations, supermarkets, and restaurants, which reinforces the Small Spatial World dynamic and reflects racialized underinvestment in Ward 8. This lack of shared social infrastructure both reflects and sustains the broader patterns of racialized disinvestment and spatial segregation across Ward 8.

7. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine how Black homeowners in Ward 8, D.C., navigate neighborhoods with structural disinvestment when seeking essential services and to explore the motivations behind their consumption patterns. By combining a Small Spatial World adaptation of Small World Theory with Racialized Capitalism, along with insights from Social Capital Theory and Pattillo’s ethnography, we demonstrate how race, class, safety concerns, and perceived service quality influence where and how these residents shop.

Our findings show that nearly all Black homeowners (69%) exclusively shop outside of Ward 8, while the remaining participants exhibit a mix of shopping both inside and outside the ward. The most significant factors influencing their decisions were safety and security, better product selection, and the limited options available within Ward 8. Although longer-term residents show signs of shopping locally, the sample size was too small to confirm the significance of this trend. For the participants, the results indicate that quality and convenience are the most important factors, with latent factors such as ease of access, parking, store cleanliness, and product variety being the strongest predictors of exclusively shopping outside Ward 8.

Ultimately, this study shows that even without formal connections or neighborhood “third places,” Black homeowners in Ward 8 create a kind of micro-network within a small spatial world where consumption choices are driven not by personal ties but by shared routines. These routines are seen as an implicit response to racial capitalism that naturally develops after decades of underinvestment and devaluation, which operate below the level of conscious choice.

Despite current local government and private economic investments in Ward 8, the lack of neutral “third places” and the dominance of Outside-only patterns highlight the urgent need for macro-level interventions to break silos, identify, facilitate engagement, and support the voices of Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8. It is also essential to reinject capital, governance, and community voice into the Ward’s collective economy. By redesigning policy levers on a large scale and ensuring proper implementation and oversight of these strategies, D.C.’s local government and Ward 8 can develop the social and commercial infrastructure (including proper “third places”) that anchors local shopping, fosters trust, and counteracts the effects of structural barriers created by racialized capitalism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of the District of Columbia (protocol code IRB #2261552-13, approved on December 3, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and confidentiality protections before beginning the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to concerns regarding privacy and confidentiality. However, the survey instrument is provided in the appendix for replication purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Use of Generative AI Disclosure

During the preparation of this manuscript, the corresponding author utilized OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-4 model) to assist in text development and create visualizations for data presentation. All content was carefully reviewed and revised to ensure academic accuracy and integrity. The author takes full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript and any supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| LIS |

Library and Information Sciences |

| ANC |

Advisory Neighborhood Commissions |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| N |

Sample Size |

| β |

Regression coefficient |

| SE |

Standard Error |

| z |

z-score |

| p-value |

Probability value |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1: Black Homeowner Instrument

Table A1.

This appendix includes the full survey instrument used in the study titled “Spatial Disinvestment and the Small Spatial World: Essential-Service Shopping Patterns Among Black Middle-Class Homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.” The Black Homeowner Survey was a custom-designed tool created to explore how Black middle-class homeowners make retail shopping decisions within a context of racialized disinvestment.

Table A1.

This appendix includes the full survey instrument used in the study titled “Spatial Disinvestment and the Small Spatial World: Essential-Service Shopping Patterns Among Black Middle-Class Homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.” The Black Homeowner Survey was a custom-designed tool created to explore how Black middle-class homeowners make retail shopping decisions within a context of racialized disinvestment.

| Black Homeowner Survey Instrument |

| Number # |

Questions |

Choices |

| 1 |

Do you provide consent to participate in this survey? |

Yes

No |

| 2 |

What is your age range?

|

Under 25

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

65 and above

Prefer not to answer |

| 3 |

What is your gender identity?

|

Male

Female

Non-binary/third gender

Transgender

Prefer not to say

|

| 4 |

How long have you lived in your Ward 8, D.C., neighborhood?

|

Less than 1-year

1-3 years

4-6 years

7-10 years

10 -14 years

15- 19 years

20 years or more

|

| 5 |

Do you identify as Black or African American?

|

Yes, I identify solely as Black or African American

Yes, I identify as Black or African American and also identify as belonging to one or more other groups.

No

|

| 6 |

What is your highest level of education?

|

Trade School Certification (e.g., Plumber, Commercial Driver's License)

Associate degree

Bachelor's degree

Master's degree

Doctorate or professional degree

Prefer not to answer |

| 7 |

What is your annual household income?

|

Under $50,000

$50,000 - $99,999

$100,000 - $149,999

$150,000 -$199,999

$200,000 -$249,999

$250,000-$499,999

$500,000 and above

Prefer not to answer |

| 8 |

Do you own and occupy a home in Ward 8, D.C.?

|

I own and occupy a home in Ward 8, D.C.

I own but do not occupy a home in Ward 8, D.C. |

| 9 |

Where do you primarily frequent restaurants or other retail goods (e.g., haircare products, liquor stores, and bookstores)? |

Inside Ward 8, Washington, D.C.

Outside Ward 8 but within Washington, D.C.

Primarily in Maryland

Primarily in Virginia

I primarily order delivery and shop online |

| 10 |

Where do you primarily purchase your groceries and everyday supplies?

|

Inside Ward 8, Washington, D.C.

Outside Ward 8 but within Washington, D.C.

Primarily in Maryland

Primarily in Virginia

I primarily order delivery and shop online |

| 11 |

Where do you typically purchase gas?

|

Inside Ward 8, Washington, D.C.

Outside Ward 8 but within Washington, D.C.

Primarily in Maryland

Primarily in Virginia

I do not purchase gas |

| 12 |

Which, if any, of the below lead you to seek essential services (grocery stores, healthcare, gas stations) outside Ward 8, Washington, D.C.? (Select all that apply.)

|

Customer service is better elsewhere.

Cleanliness is better elsewhere.

Safety and security concerns.

The convenience of shopping locations and parking is better elsewhere.

The prices of goods and services are better elsewhere.

The quality of goods and services is better elsewhere.

Product selection is better elsewhere.

There is a lack of options and trust in the resources available in Ward 8.

|

| 13 |

Which of the following best describes your primary motivation for purchasing a home and living in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.? (Select one option.)

|

To contribute to social justice efforts, such as "buying back the block" and uplifting the local Black community

To create opportunities for generational wealth through homeownership

Both social justice efforts and generational wealth opportunities

None of the above |

Appendix A.2: Table of Sample Demographics (N = 58)

Table A2.

reports demographic characteristics for N = 58 Black homeowners in Ward 8. Continuous measures (Age, Tenure) show N, mean, SD, median, and range. Categorical measures (Income, Education) show counts and percentages; the median income bracket is $ 125,000, and the modal/median education is a Master's degree.

Table A2.

reports demographic characteristics for N = 58 Black homeowners in Ward 8. Continuous measures (Age, Tenure) show N, mean, SD, median, and range. Categorical measures (Income, Education) show counts and percentages; the median income bracket is $ 125,000, and the modal/median education is a Master's degree.

| Variable |

Variable |

N |

Percent |

Mean |

SD |

Median |

Range |

| Age (years) |

|

58 |

|

47.5 |

11.8 |

49.5 |

22-68 |

| Tenure (years) |

|

58 |

|

12.4 |

5.1 |

12.5 |

1-20 |

| Income |

Under $50,000 |

5 |

8.6% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

$50K-$99K |

11 |

19.0% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

$100K-$149K |

13 |

22.4% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

$150K-$199K |

12 |

20.7% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

$200K-$249K |

5 |

8.6% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

$250K-$499K |

7 |

12.1% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

≥ $500K |

0 |

0.0% |

|

|

|

|

| Income |

Median bracket |

|

|

|

|

$125K |

|

| Education |

Trade school certificate |

5 |

8.6% |

|

|

|

|

| Education |

Associate degree |

3 |

5.2% |

|

|

|

|

| Education |

Bachelor’s degree |

3 |

5.2% |

|

|

|

|

| Education |

Master’s degree |

21 |

36.2% |

|

|

|

|

| Education |

Doctorate/professional |

18 |

31.0% |

|

|

|

|

| Education |

Mode & Median |

|

|

|

|

Master’s |

|

Appendix B

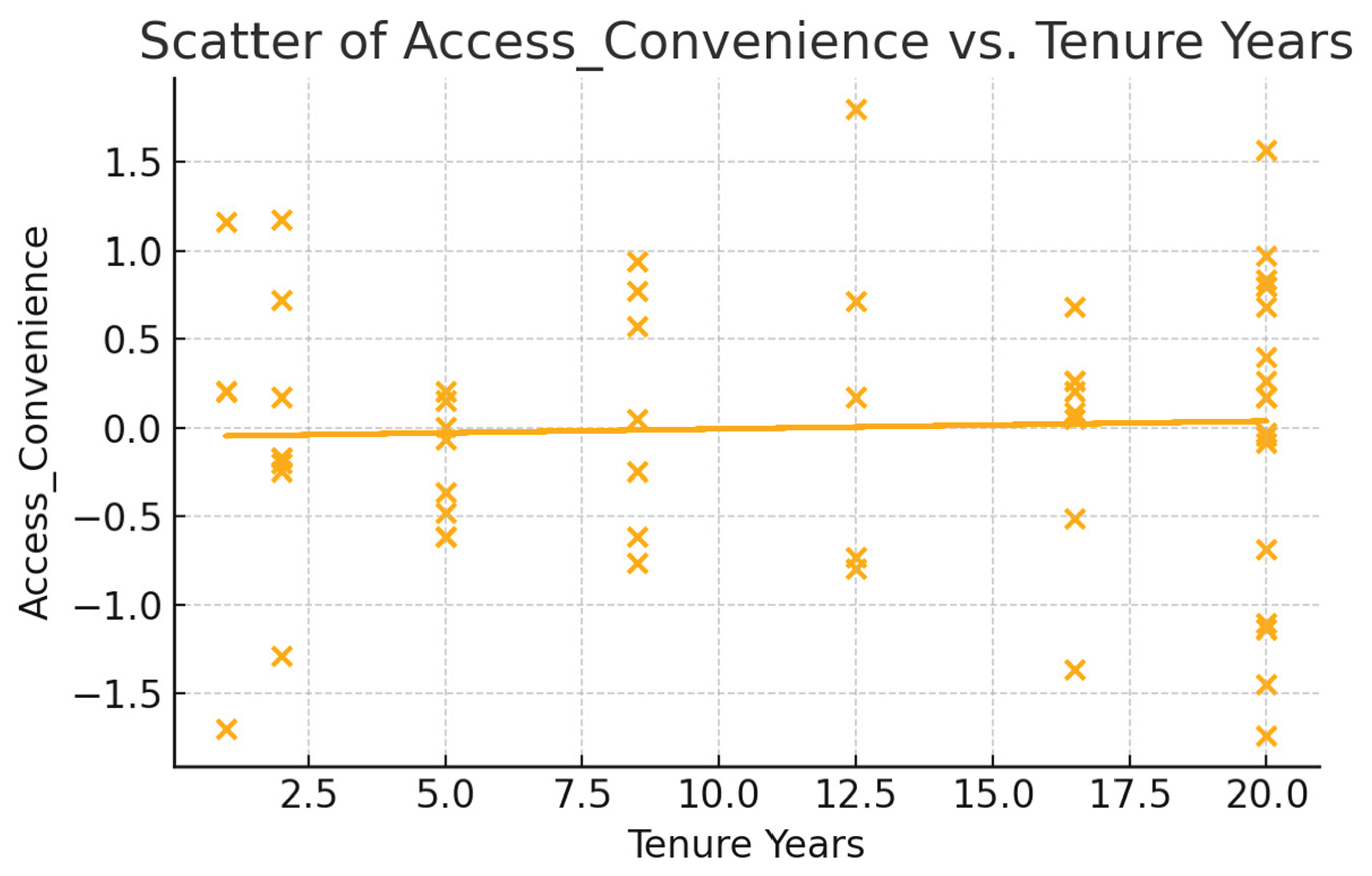

Appendix B.1: Scatterplot of Access & Convenience Factor Scores by Tenure Years

Figure A1.

This figure shows a scatterplot illustrating the relationship between respondents' length of residence in Ward 8 (Tenure Years) and their standardized scores on the Access & Convenience factor. Each point represents an individual respondent. The fitted trend line (in orange) indicates no strong linear relationship between tenure and Access & Convenience motivations, suggesting that logistical and spatial concerns (e.g., parking, safety, lack of options) influence shoppers across different levels of neighborhood tenure. This supports the idea that such problems are common, rather than limited to newer or longer-term residents. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

Figure A1.

This figure shows a scatterplot illustrating the relationship between respondents' length of residence in Ward 8 (Tenure Years) and their standardized scores on the Access & Convenience factor. Each point represents an individual respondent. The fitted trend line (in orange) indicates no strong linear relationship between tenure and Access & Convenience motivations, suggesting that logistical and spatial concerns (e.g., parking, safety, lack of options) influence shoppers across different levels of neighborhood tenure. This supports the idea that such problems are common, rather than limited to newer or longer-term residents. Note: Graphic generated with GenAI.

References

- DC Office of Planning. Ward 8 Heritage Guide: A People’s History of Anacostia, Congress Heights, and Washington Highlands. 2023. Available online: https://planning.dc.

- Pattillo, M. Black Middle-Class Neighborhoods. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2005, 31, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattillo, M. Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. S.; Denton, N. A. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. In Social Stratification, Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue, T. J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- DC Health Matters. Ward 8 Profile. Available online: https://www.dchealthmatters.

- Census Reporter. Ward 8, DC – Profile Data (2023). Available online: https://censusreporter. 6100.

- Chatman, E. A. A Theory of Life in the Round. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999, 50, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R. D. G. Introduction: Race, Capitalism, Justice. Boston Rev., . Available online: https://www.bostonreview. 31 October.

- Pulido, L. Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial Capitalism. Capital. Nat. Social. 2016, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. J. Democracy 1995, 6, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, A. B. The Problem of Trust; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, N. Racial Capitalism. Harv. L. Rev. 2013, 126, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R. M. Beyond the Ghetto: The Black Middle Class and Neighborhood Attainment. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of New York at Albany, Albany, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, E. A. Alienation Theory: Application of a Conceptual Framework to a Study of Information among Janitors. RQ 1990, 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, E. A. The Information World of Retired Women; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, G.; Jaeger, P. T. Small Worlds, Lifeworlds, and Information: The Ramifications of the Information Behaviour of Social Groups in Public Policy and the Public Sphere. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal.

- Babb, T. N. Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City—A New Perspective of Middle Class. Rev. Commun. 2009, 9, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattillo-McCoy, M. E.; Pattillo, M. E. Middle Class, yet Black: A Review Essay. Afr. Am. Res. Perspect. 1999, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Inequality in Social Capital. Contemp. Sociol. 2000, 29, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, C. Human Capital. In Handbook of Cliometrics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural capital. J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecka, J. Social Capital in the Perspective of Modern Challenges and Threats. Horyzonty Polityki 2025, 16, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siisiainen, M. Two Concepts of Social Capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam. Int. J. Contemp. Sociol. 2003, 40, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition; Zed Press: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, J. Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction in America; Russell & Russell: New York, NY, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Go, J. Three Tensions in the Theory of Racial Capitalism. Sociol. Theory 2020, 39, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. P. Race and America’s Long War; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alagraa, B. Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism: Thirty-Five Years Later [Review of Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, by C. J. Robinson]. CLR James J. 2018, 24, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. J. Capitalism, Slavery and Bourgeois Historiography. Hist. Workshop 1987, 23, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, R. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, E. S.; Vasudevan, P.; Bailey, Z.; Patel, S.; Robinson, W. R. Racial Capitalism within Public Health—How Occupational Settings Drive COVID-19 Disparities. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. The Trap of “Racial Capitalism. ” Eur. J. Sociol. 2023, 64, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptist, E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, D. R. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph, M.; Singhal, M. Racial Capitalism. Theory Soc. 2019, 48, 851–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice. Boston Rev. 2017. Available online: http://bostonreview.

- Harvey, D. The Enigma of Capital: And the Crisis of Capitalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, B. J. Why Buy a Home? Race, Ethnicity, and Homeownership Preferences in the United States. Sociol. Race Ethn. 2018, 4, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Institute. Explaining the Black-White Homeownership Gap: A Closer Look at Disparities across Local Markets. 2020. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101160/explaining_the_black-white_homeownership_gap_a_closer_look_at_disparities_across_local_markets_0.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Creswell, J. W.; Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M. A.; Adnan, T. H. Requirements for Minimum Sample Size for Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, YE01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, M. A.; Sorensen, J. Repackaged “Urban Renewal”: Issues of Spatial Equity and Environmental Justice in New Construction, Suburban Neighborhoods, and Urban Islands of Infill. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 464–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, T. Functions of Social Capital—Bonding, Bridging, Linking. Social Cap. Res. 2018, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, R. E.; Randolph, L. A. The National Response to Richard M. Nixon’s Black Capitalism Initiative: The Success of Domestic Détente. J. Black Stud. 2001, 32, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M. The Black Panther Party and the Struggle for Human Rights. Spectrum J. Black Men 2016, 5, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villemez, W. J.; Beggs, J. J. Black Capitalism and Black Inequality: Some Sociological Considerations. Soc. Forces 1984, 63, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, E. O. Is Black Capitalism Still a Myth? Mon. Rev. 2024, 76, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, K. L.; Hill, J. D. The Predatory Rhetorics of Urban Development: Neoliberalism and the Illusory Promise of Black Middle-Class Communities. Du Bois Rev. 2023, 20, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danley, S.; Blessett, B. Nonprofit Segregation: The Exclusion and Impact of White Nonprofit Networks. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2022, 51, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).