1. Introduction

Polyethersulfone (PES) is an advanced polymeric material characterized by high mechanical strength, thermal resistance, and excellent chemical properties. Its unique structure, based on aromatic rings connected by sulfone and ether bridges, provides exceptional stability, making it one of the most commonly used materials in membrane technology. PES membranes have a wide range of applications in various industries, such as aerospace, medicine (e.g. production of hemodialysis filters), water treatment, and wastewater treatment[

1]. PES membranes come in different forms, such as flat, spiral, or tubular, which differ in construction and application. In particular, tubular membranes, due to their high resistance to contamination and ease of cleaning, are frequently used in challenging industrial conditions [

2].

In the context of the rubber industry, ultra-filtration using PES membranes can play a crucial role in the optimization of wastewater treatment processes. Reuse of treated wastewater in industrial facilities allows the implementation of a closed water loop, reducing the demand for fresh water and decreasing the amount of discharged wastewater, contributing to the realization of the principles of sustainable development. The implementation of this technology enables compliance with stringent environmental standards and generates economic benefits by reducing costs associated with water purchase and wastewater disposal. Such systems, depending on the level of wastewater contamination, e.g., used in the food industry, can achieve recovery rates of up to 95% [

3].

Ultra-filtration (UF) is an advanced membrane separation technique that effectively removes suspended particles, macromolecules, and organic contaminants from aqueous solutions. As a result, ultra-filtration finds widespread application in various sectors, such as water treatment, wastewater treatment, food processing, and pharmaceutical industries [

4]. One of the limitations of the ultra-filtration process using PES membranes is the fouling phenomenon, which reduces process efficiency by membrane clogging. To minimize this effect, various modifications of the PES material are employed [

5,

6].

The inherent hydrophobic nature of polyethersulfone (PES) makes membranes prone to fouling, which can result in reduced efficiency, increased operational costs, frequent chemical cleaning requirements, and ultimately shorter membrane lifespan [

7,

8,

9]. Sequently, research on PES membrane modifications focuses on enhancing their hydrophilicity, selectivity, and stability. These modifications are achieved primarily by incorporating nanomaterials into the membrane surface to alter its roughness [

10]. Compared to integrally asymmetric membranes, nanocomposite membranes fabricated with nanoparticles demonstrate superior permeability and reduced fouling intensity. Studies have shown that membranes incorporating inorganic particles such as zeolites, silica, or metal oxides within their structure also exhibit improved transport properties [

11].

Examples of such modifications include the integration of membrane material with spherical silica particles [

12] or the use of a mixed matrix membrane (MMM) with the addition of carbon nanotubes prepared by phase inversion [

13]. Studies show that increasing the concentration of carbon in the membrane material results in increased nominal permeability [

14].

Mixed matrix membranes, depending on the nanofillers used, acquire different functional properties. Research on the impact of additives such as TiO2 and SWCNT-COOH demonstrates that when these membranes are used for ultra-filtration of wastewater with organic contaminants, they significantly alter the parameters of the UF process. PES-TiO2 membranes exhibit excellent antifouling properties but have poorer separation coefficients, while PES-SWCNT-COOH membranes show the highest cleaning efficiency but quickly lose permeability [

15]. Other additives used to modify PES membranes include cellulose nanocrystals, which significantly improve membrane hydrophilicity [

16]. One of the effects of modifying ultrafiltration membranes using nanofillers is the creation of nanohybrid membranes. This technology involves creating a two-layer membrane. Such membranes are produced using dry-wet phase inversion to form flat sheet membranes. This study is expected to provide insight into improving new strategies that facilitate PES membrane separation based on PES membranes as an effective and efficient technology for treating industrial water [

17].

In industrial applications using filtration membranes, bio-fouling, or colonization of membranes by microorganisms, often occurs. Bio-fouling is a serious problem in membrane systems because it requires regular chemical cleaning, which shortens the membrane’s lifespan and reduces product quality. To prevent this, biocides are added [

18].

Due to modifications, PES membranes, especially in tubular form, exhibit excellent filtration performance, high resistance to fouling, and long lifespan, suggesting that they would be an ideal solution for applications such as wastewater treatment in the rubber production process.

Wastewater from the rubber industry is characterized by, among other things, a high content of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and high concentrations of non-ionic surfactants (NIS). This characteristic of wastewater pollution is caused by the production technology, where rubber products are vulcanized using steam. This process involves heating the rubber compound in closed molds or in an autoclave using steam, which allows for effective crosslinking of rubber molecules under high temperature and humidity conditions. However, the presence of steam introduces additional challenges in terms of adhesion of adhesion rubber to the mold and protection of production equipment. Steam, as a heating medium, can increase the risk of the rubber compound sticking to the mold and contribute to the formation of deposits and corrosion on the mold surface. To counteract these problems, specialized anti adhesive agents are used that meet the specific requirements of processes carried out under steam conditions. The use of anti adhesive agents in the steam vulcanization process is crucial for obtaining high-quality rubber products and for production efficiency. The most commonly used agents, such as talc, silica flour, silicone emulsions, wax emulsions, or fluoropolymer preparations, must be adapted to specific process conditions, such as temperature, humidity, and the intense action of steam. The appropriate selection and application of these agents not only prevents rubber from sticking to molds, but also extends the life of the molds, increases production efficiency, and reduces costs associated with equipment maintenance. However, these agents, which are necessary to carry out a proper and effective vulcanization process, introduce an unfavorable environmental aspect by releasing toxic substances into the aquatic environment. Therefore, research on environmentally friendly anti adhesive agents is being conducted [

19,

20]

However, the topic of wastewater treatment from the rubber production industry does not have abundant resources in the available scientific literature and is still a novelty. Until 2010, no more than 10 articles on this topic per year can be found, around 15 articles in 2015, and after 2020, the number of articles in this topic significantly increases to 40-50 articles per year. From the available literature, up to 48% of all articles on this topic have been published in the last 5 years [

21]. Therefore, it is evident that this is an intensively developing research area that needs further investigation.

The main goal of the conducted research was to determine the suitability of the ultra-filtration process on modified PES membranes for use in a closed water system in a production plant in southern Poland, specializing in the production of rubber components for the automotive industry. The intended application is to enable the reuse of process water from washing vulcanized rubber hoses, which currently goes to sewage systems. This process would include preliminary treatment and water recovery for reuse in production processes. Particular attention was focused on parameters such as the content of non-ionic surfactants (NIS) and chemical oxygen demand (COD), which determine the main contaminants in this type of wastewater. Reducing these parameters determines the effectiveness of process water treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Investigated Wastewater

The Wastewater examined originated from the washing process of vulcanized rubber hoses prior to their final assembly. The washing of the rubber hoses was performed using warm water without detergent additives. The primary source of contaminant in this wastewater consisted of surfactants derived from the anti-adhesive lubricant (Rheolase 487LG) used during the rubber vulcanization process using steam. This lubricant originated from the vulcanization stage preceding the washing process.

The lubricant adhered to the rubber hoses when operators of steam autoclaves applied it during the placement of the hoses in shaping molds. This application served two purposes: (1) to reduce friction and facilitate the molding process, and (2) to protect the rubber hoses from mechanical damage and adhesion to the molds. The Rheolase 487LG lubricant exhibits high water solubility, fully dissolving at temperatures exceeding 45 ° C [

22]. This property influenced the decision to conduct surfactant separation studies at a wastewater temperature of approximately 35 ° C.

A high level of chemical oxygen demand (COD) is characteristic of organic antiadhesive agents, which contain substances that are readily oxidized in aqueous environments, such as fats, oils, waxes, and water-soluble organic compounds.

As a result, the investigated wastewater exhibits the following concentrations of pollutants:

The target values expected after the ultrafiltration (UF) process are:

2.2. Ultrafiltration Process

The studies conducted used 18 tubular membranes of the ESP04 type, manufactured by PCI Membranes and made of modified polyethersulfone (PES). The ultrafiltration process was carried out using a pilot installation, UF-1, supplied by APEKO Sp. z o.o. (Poland). The selection of these membranes was based on their well-documented advantages, which are particularly beneficial for the intended application.

This type of membrane has previously been used in studies conducted by Woźniak P. and Gryta M. [

23] on wastewater from car washed wastewater, where their excellent separation properties were confirmed for similar contaminants (high surfactant content, elevated levels of COD, and waxes).

Due to their tubular design, these membranes are especially effective in filtering liquids with high viscosity and significant amounts of suspended solids. Their wide flow channels are highly resistant to clogging. Additionally, the surface of these membranes is protected against biofouling using a biocide. The biocide used is Proxel GXL, provided by Azelis Essential Chemicals, which is a water-based agent containing 20% dipropylene glycol.

2.3. Experimental Installation

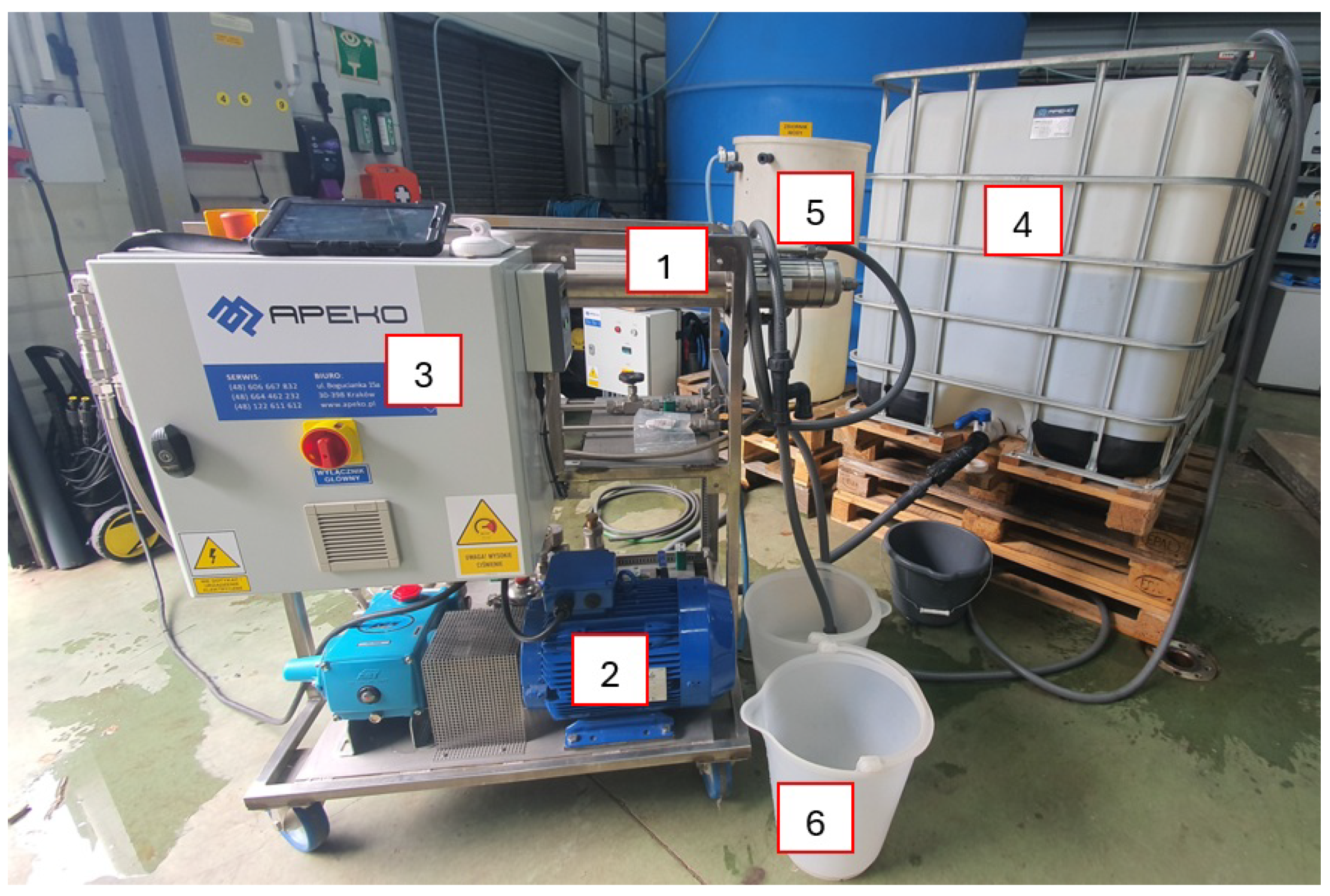

For the study on the efficiency of industrial wastewater treatment using membranes made from modified PES, a pilot installation UF-1 type supplied by APEKO Sp. z o.o. was used

Figure 1. The nominal installation capacity, achieved with new membranes and using clean water (softened municipal tap water was used for testing), is 221 L/m²/h.

Components of the installation

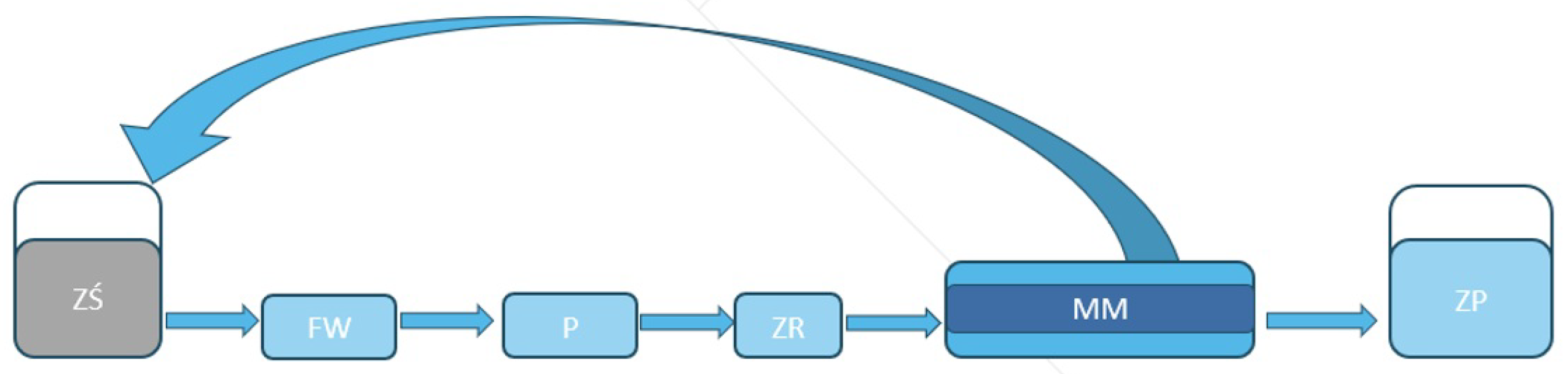

Figure 2:

1. Cylindrical PCI B1 module equipped with 18 membranes

2. High-pressure circulation pump CAT

3. Electrical box with control panel

4. IBC 100L tank, wastewater buffer for ultrafiltration

5. Cleaning chemical tank

6. Standard permeate container, plastic bucket with a measuring scale

ZŚ – Wastewater tank, IBC 1000 L

FW – Inlet filter, string-wound 50 µm

P – Process pump, high pressure CAT model 1051

ZR – Control valve that regulates the inlet flow

MM – PCI B1 membrane module with PCI ESP04 membranes

ZP – Permeate tank

The installation was equipped with a membrane module with the following parameters:

Membrane material: modified PES

Diameter of the cylindrical B1 module with 18 membranes: 100 mm

Number of internal channels: 18

Diameter of internal channels: 12.7 mm

Membrane length: 1200 mm

Operating range of pH: from 1 to 14

Maximum operating pressure: 30 bar

Maximum operating temperature: 65 ° C

Hydrophilicity: 4 (scale from 1 to 5 according to PCI Membrans scale)

Molecular Weight Cut-Off: 4 kDa

Solvent resistance: insensitive

Active filtration area: 0.9 m² [

24].

2.4. Membrane Regeneration

Membrane regeneration was carried out through a chemical cleaning process using two Ecolab agents from the Ultrasil series:

P3 Ultrasil 02

P3 Ultrasil 11

P3 Ultrasil 02 is an alkaline liquid cleaning detergent based on surfactants and sequestrants[

25]. P3 Ultrasil 11 is an acid cleaning agent used as a complement to alkaline cleaning (with P3 Ultrasil 02). The purpose of the alkaline agent is to remove organic contaminants, while the acidic agent eliminates mineral residues [

26].

The chemical cleaning solution for the membranes was prepared according to the manufacturer’s recommendations: 50 g of the alkaline agent Ultrasil 11 and 30 ml of the acidic agent Ultrasil 02 were dissolved in 50 L of softened tap water from the facility’s water treatment station. The prepared solution was heated to 50 ° C and then pumped through the membrane module for 1 hour, while maintaining a constant feed pressure of 10 bar.

2.5. Analyzed Parameters

The study determined the transport and separation conditions of the membranes during testing of the membrane module. Changes in the volumetric permeate flow over time / depending on the amount of filtered wastewater were assessed. Approximately 2 m³ of wastewater was filtered in three research cycles

The permeate flux was calculated using the formula:

where:

J – volumetric permeate flux [L/m²·h]

V – volume of permeate obtained during time t [L]

F – active membrane area [m²]

t – time [h]

The nominal permeate flux (for clean tap water) for the tested membrane module was:

The contaminant rejection coefficient for the tested membrane was calculated using the following formula:

where:

R – contaminant rejection coefficient [%]

Cp - contaminant concentration in the permeate

Cn - contaminant Concentration in the feed wastewater

During the tests, parameters of the raw wastewater and the obtained permeate were determined, such as the chemical oxygen demand (COD) and the content of nonionic surfactants (NIS) under various ultrafiltration process conditions.

The analysis of these parameters was performed using a Hach DR9000 spectrophotometer and cuvette tests LCI400 (for COD analysis) and LCK433 (for nonionic surfactant analysis), supplied by Hach Lange Poland Sp. z o.o. On the basis of these parameters, separation coefficients (R, %) were calculated for key contaminants present in this wastewater.

2.6. Research Methodology

Due to technical limitations, it was not possible to connect the pilot installation directly to the fresh wastewater stream. Therefore, the wastewater was collected from a common sump that serves all the washing machines in the production hall into a 1 m³ plastic IBC tank and subsequently subjected to ultrafiltration from this tank. To evaluate the performance of the membrane installation, three consecutive trials were carried out, each maintaining a constant feed flow rate of 23 L/min. As the ultrafiltration efficiency decreased, the feed pressure gradually increased from an initial value of 15 bar to 25 bar. Higher pressure was achieved by adjusting the pump operation, while constant feed flow was maintained by regulating the inlet proportional valve. The three filtration cycles were performed in the following sequence:

Filtration of 600 L of wastewater in a closed loop, yielding 510 L of permeate over six hours, with an initial feed pressure of 15 bar increased to 20 bar by the end of the cycle.

Chemical cleaning cycle at 50°C for 1 hour, followed by rinsing with clean water.

Filtration of 600 L of wastewater in a closed loop, yielding 570 L of permeate over six hours, with an initial feed pressure of 15 bar increased to 25 bar by the end of the cycle.

Chemical cleaning cycle at 50°C for 1 hour, followed by rinsing with clean water.

Filtration of 600 L of wastewater in a closed loop, yielding 570 L of permeate over six hours, with an initial feed pressure of 15 bar increased to 25 bar by the end of the cycle.

Chemical cleaning cycle at 60°C, followed by rinsing with clean water.

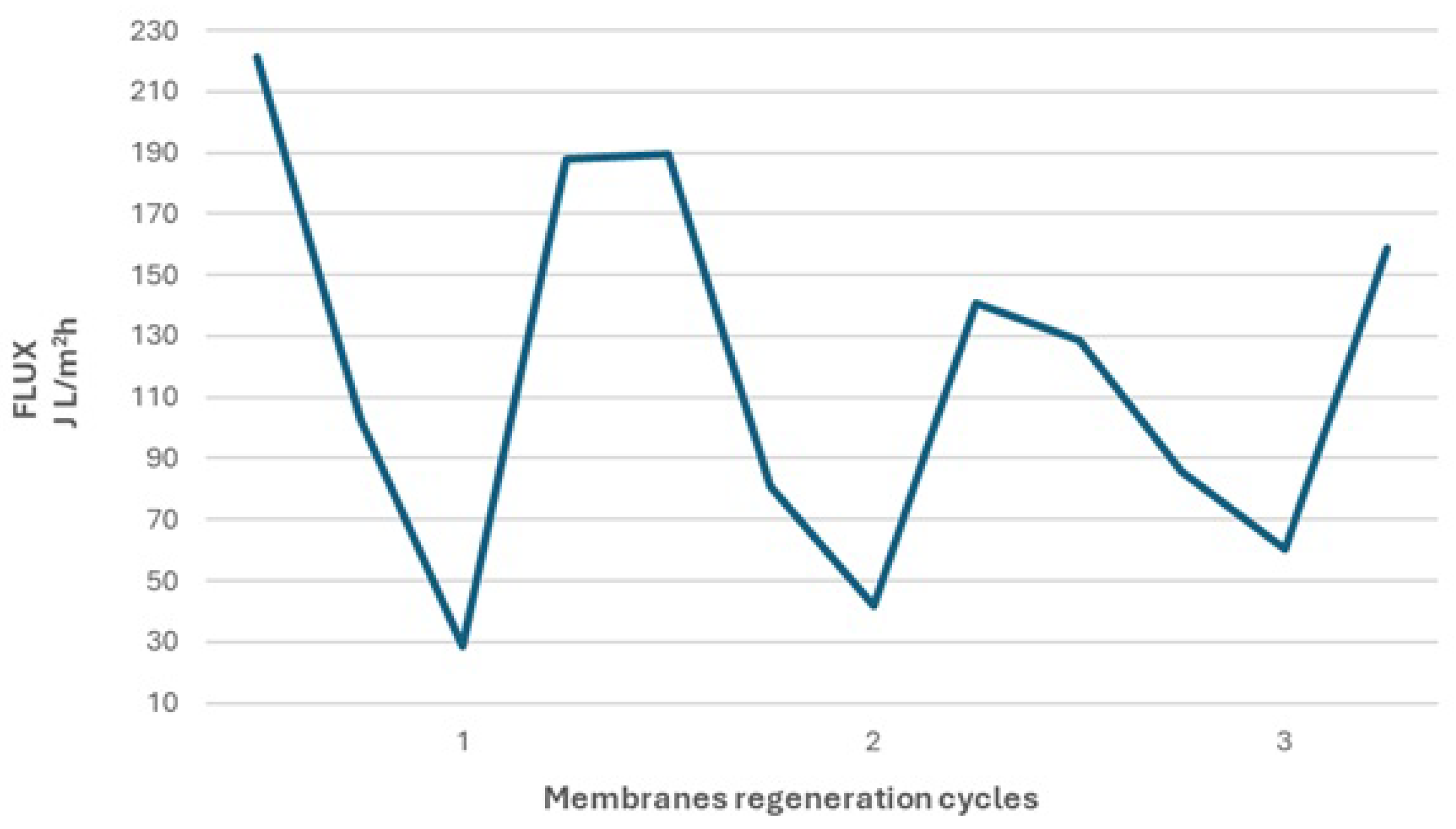

After each chemical cleaning cycle, membrane performance was evaluated by filtration using clean softened municipal tap water to assess the effectiveness of the cleaning process and the potential for membrane regeneration, thereby mitigating fouling phenomena.

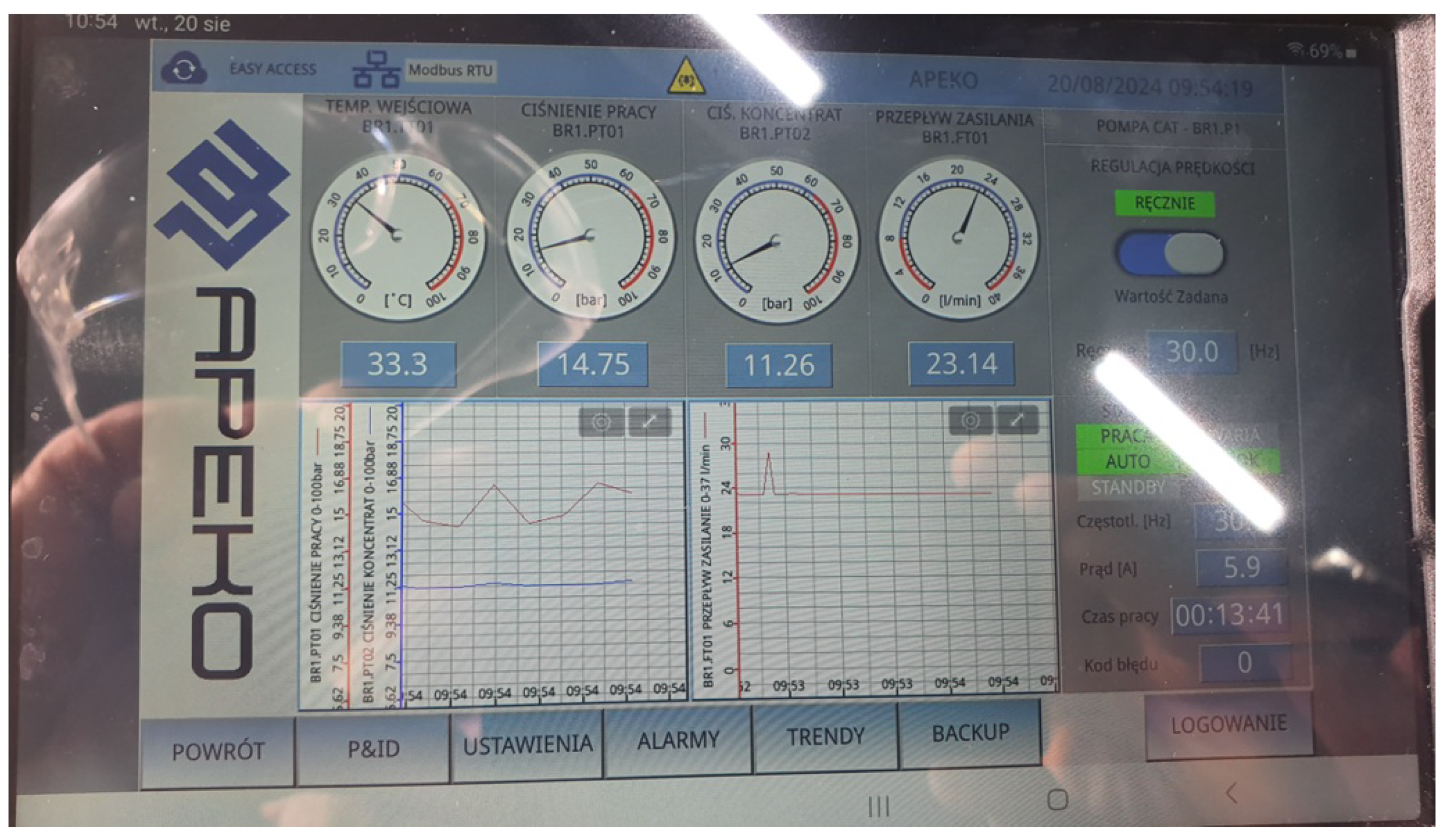

The operation of the membrane installation was monitored using the electronic control panel of the UF-1 device (

Figure 3), which recorded all process parameters, including time, flow rate, temperature, pressure, etc.

To ensure comparable initial conditions, after each trial the membranes were regenerated by chemical cleaning using a solution of water with alkaline and acidic agents at 50°C for one hour. The third chemical cleaning cycle was performed at an elevated temperature of 60°C. This variation was designed to evaluate whether the temperature of the cleaning solution influences cleaning effectiveness.

The chemical cleaning procedure, intended to restore initial membrane performance by removing inorganic fouling with acids and organic fouling with alkaline agents, is widely recognized in the literature as highly effective. However, contaminants adhering to the membrane surface, such as nonionic surfactants, are generally considered difficult to remove, although this also depends on their molecular structure.

Following chemical cleaning, the membrane module was rinsed with softened water at a neutral pH. After rinsing, membrane performance was reassessed by filtration of clean and softened municipal tap water to verify the efficacy of the cleaning.

3. Results

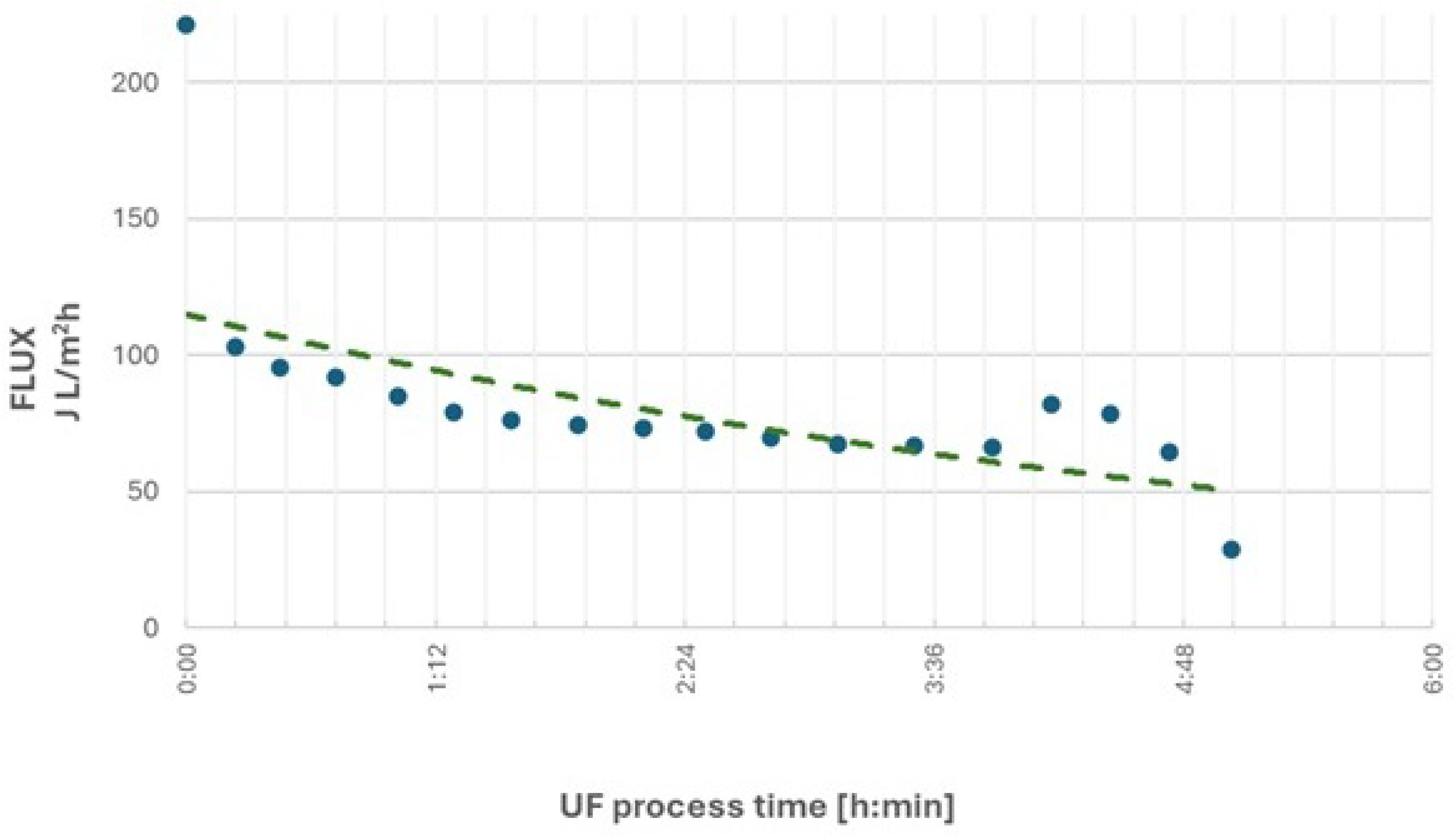

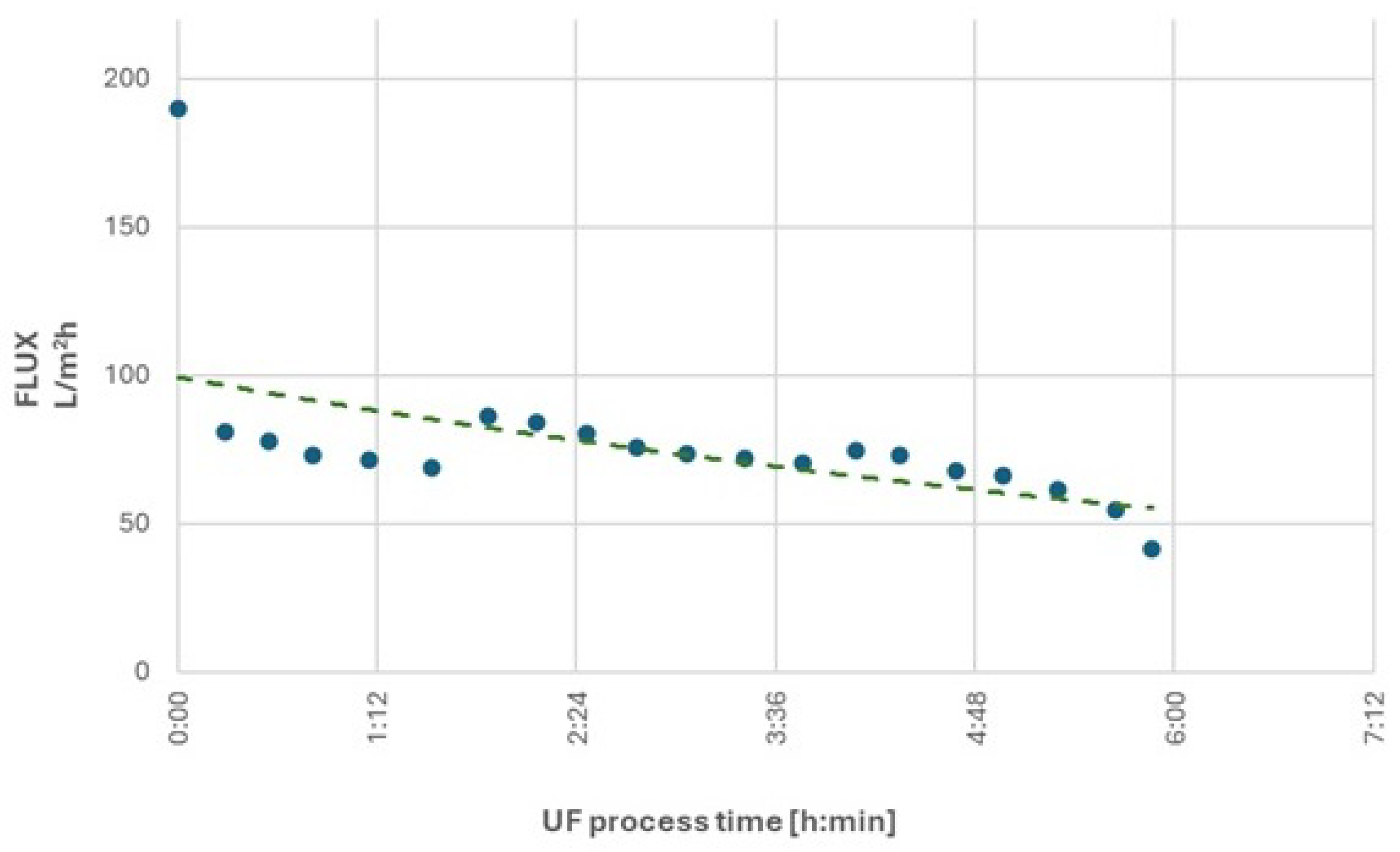

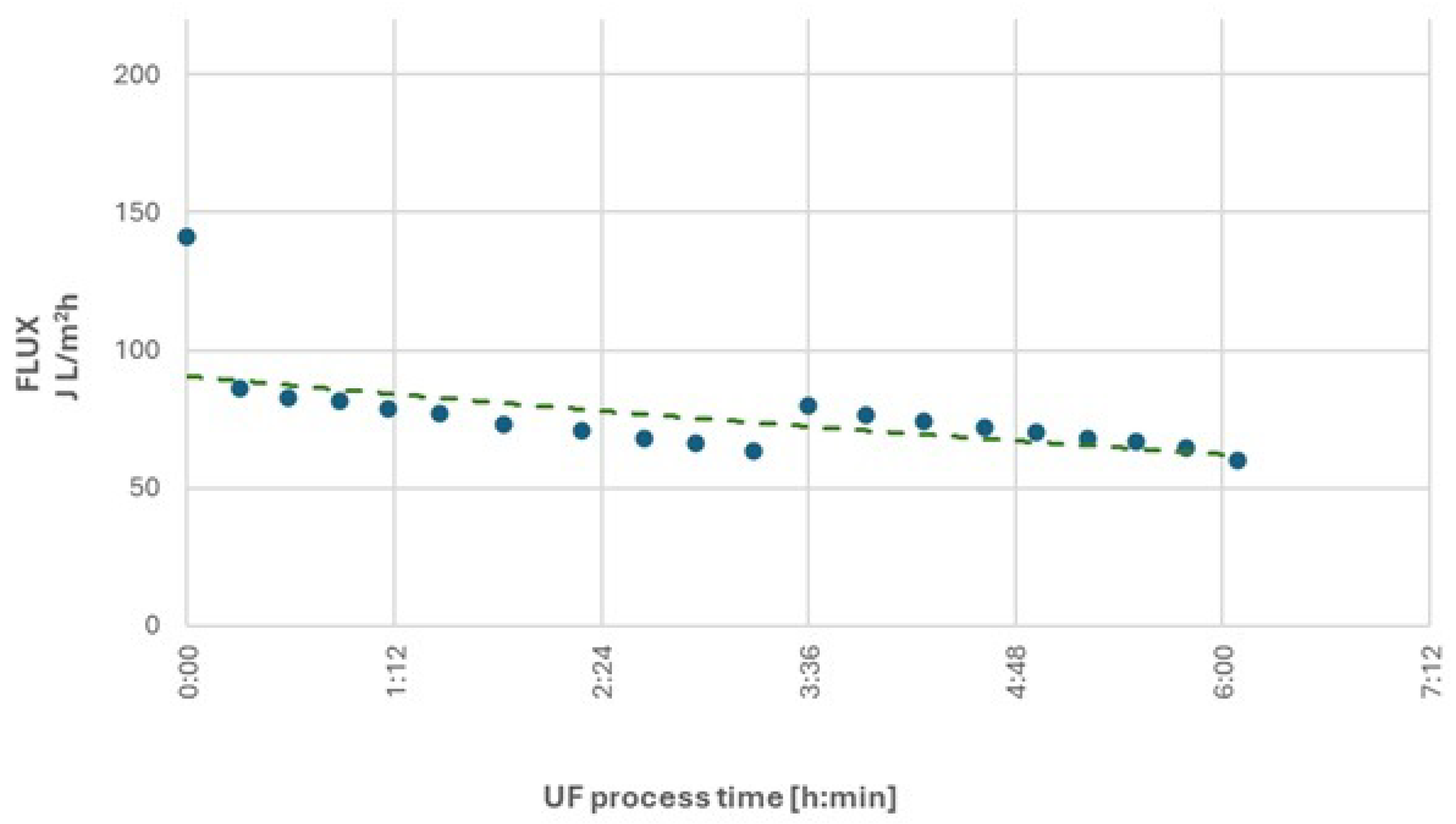

During the studies conducted, the membrane transport conditions (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) were monitored by observing changes in volumetric permeate flux (membrane performance) over time while maintaining a constant feed flow rate. Furthermore, the separation conditions of the key contaminants were analyzed by determining the concentrations of nonionic surfactants (NIS) and pollutants measured by the chemical oxygen demand (COD) parameter (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.1. First Research Cycle

The results of the first research cycle revealed significant changes in ultrafiltration performance over time. At an initial feed stream pressure of 15 bar, after obtaining approximately 400 L of permeate, a substantial decline in process efficiency was observed. The volumetric permeate flux decreased by about 40%, from an initial value of 102.8 L/m²·h to 65.9 L/m²·h. At this point, the contaminants in the remaining retentate were concentrated three times compared to the initial wastewater. To improve process efficiency, the feed pressure was increased to 20 bar, temporarily raised the permeate flux to 81.8 L/m²·h. However, after producing an additional 100 L of permeate, the performance of the process decreased markedly to 28.7 L/m²·h, leading to the termination of the first research cycle.

After obtaining 510 L of permeate and more than 5 hours of filtration, the process efficiency decreased by 70%.

A reduction in nonionic surfactant concentration was observed, with rejection rates of RNIS = 85% for the initial wastewater and RNIS = 95% for the concentrated retentate at the end of the cycle.

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) parameter decreased by RCOD = 77% for initial wastewater and RCOD = 87% for the concentrated retentate at the end of the cycle.

3.2. Second Research Cycle

In the second research cycle, the ultrafiltration process was initiated at a constant feed pressure of 15 bar. After obtaining 150 L of permeate, a decrease in process performance was observed, with the volumetric permeate flux decreasing from an initial value of 80.8 L/m²·h to 68.6 L/m²·h, representing a 15% reduction. In response, the feed pressure was increased to 20 bar, which allowed the permeate flux to increase to 86.2 L/m²·h. After producing 360 L of permeate, the efficiency of the process decreased again to 70.3 L/m²·h, indicating a further 18% decrease in membrane performance. To improve efficiency, the feed pressure was increased once more, this time to 23 bar. This adjustment resulted in a slight increase in permeate flux to 74.8 L/m²·h. Ultimately, after approximately six hours of operation, with 570 L of permeate obtained and a 20-fold concentration of retentate, the process performance fell dramatically to 41.7 L/m²·h.

After obtaining 570 L of permeate and 6 hours of filtration, the process efficiency decreased by 55%.

A reduction in nonionic surfactant concentration was observed, with rejection rates of RNIS = 79% for the initial wastewater and RNIS = 81% for the concentrated retentate.

The chemical oxygen demand parameter decreased by RCOD = 78% for the initial wastewater and RCOD = 85% for the concentrated retentate.

3.3. Third Experimental Cycle

In the third cycle of wastewater ultrafiltration, the process was initiated at a feed pressure of 20 bar. The initial permeate flux was 86.0 L/m²h and decreased linearly over time. After collecting 300 L of permeate, the volumetric permeate flux dropped to 63.5 L/m²h, corresponding to a 26% decline in performance. In response, the feed pressure was increased to 25 bar, which resulted in an increase in process efficiency to 79.8 L/m²h. The subsequent operation of the process was also characterized by a linear decrease in flux. Ultimately, after obtaining 570 L of permeate and 30 L of retentate concentrated twentyfold, the ultrafiltration performance decreased by a further 25%, reaching a value of 60.2 L/m²h, which led to the termination of the experiment.

After obtaining 570 L of permeate and a filtration time of 6 hours, a 30% decrease in process efficiency was observed.

A reduction nonionic surfactants content was achieved, with RNIS = 74% for the initial wastewater and RNIS = 94% for the concentrated retentate at the end of the cycle.

A decrease in the COD parameter was observed, with RCOD = 74% for the initial wastewater and RCOD = 89% for the concentrated retentate at the end of the cycle.

To ensure consistent initial conditions for each experimental cycle, a membrane regeneration cycle was conducted between them. As shown by the data presented in

Figure 3.4, after each regeneration cycle, the membranes recovered their performance, although to a progressively lesser extent, indicating that chemical cleaning was not completely effective. It is also noticeable that after increasing the cleaning temperature to 60°C in the final experimental cycle, the membrane regained a higher level of performance. The elevated cleaning temperature allowed for a greater degree of fouling reversibility, resulting in a 13% higher membrane efficiency compared to cleaning at 50°C.

4. Discussion

The studies and observations indicate that in each successive experiment, the obtained permeate exhibited significant turbidity removal. The product obtained in every test was visually clear, free of suspended solids and particulate matter, and showed perfect transparency.

Analysis of the parameters examined, namely COD and non-ionic surfactants (NIS), revealed that the highest contaminant separation efficiencies (RNIS = 94%, RCOD = 89%) in the permeate were achieved at the end of the cycle, during ultrafiltration of highly concentrated wastewater when the membrane was already fouled and operated under the highest applied pressure of 25 bar.

The improvement in membrane separation performance during operation is attributed to the formation of a filtration cake layer on the membrane surface. The accumulation of contaminants in the membrane leads to the development of a cake layer which, despite restricting the flow of the permeate and reducing process flux, simultaneously improves the membrane’s separation capabilities of the membrane. This phenomenon has been observed and described, among others, by M. Gryta and P. Woźniak during studies of tubular polymer membranes in the ultrafiltration of car wash wastewater [

23].

The decline in ultrafiltration process performance, manifested as a decrease in volumetric permeate flux, is attributed to membrane fouling caused by concentration polarization, adsorption of feed components within the porous membrane structure, pore blocking, and the formation of a gel layer on the membrane surface. Membrane fouling is considered reversible if it can be removed by physical methods such as adjusting operational parameters or rinsing the membrane with water. On the contrary, fouling resulting from adsorption and entrapment of dissolved contaminants within membrane pores, which requires chemical cleaning, is regarded irreversible [

8]. In the membranes case of the studied made from modified polyethersulfone (PES), the fouling was only partially mitigated, even after chemical cleaning.

Chemical cleaning enabled the recovery of 85% of the initial permeate flux after the first cycle, 63% after the second cycle, and 74% after the third cleaning performed at an elevated cleaning solution temperature. These results suggest that increasing the cleaning temperature improves the efficiency of chemical cleaning and allows for more effective mitigation of membrane fouling. Another critical factor that influences the effectiveness of chemical cleaning is the duration of the cleaning process. In the present study, the cleaning time was set to 1 hour, based on the assumption that longer operational interruptions would be undesirable under real-world conditions, making this duration optimal for process downtime.

Research conducted by Gryta and P. Woźniak on reducing fouling during ultrafiltration of car wash wastewater demonstrated that 30 minutes of chemical cleaning yielded satisfactory results, enabling recovery of 70–80% of membrane performance [

9]. Accordingly, a one hour cleaning time was deemed optimal for the present study.

Despite its effectiveness, chemical cleaning has drawbacks, including potential damage to membrane seals, possible negative environmental impacts, and surface degradation of the membrane due to the alkaline nature of cleaning agents, which can deteriorate membrane separation properties [

27]. No adverse effects of chemical cleaning were observed during the conducted experiments; however, only three cleaning cycles were performed.

The investigated membrane made of modified polyethersulfone (PES) demonstrated effective separation of target contaminants, achieving separation coefficients exceeding 85% for COD and more than 80% for nonionic surfactants (NIS), which renders it promising for potential application in a water recovery system within the examined rubber manufacturing facility. However, a significant drawback was its susceptibility to fouling, which rapidly caused a substantial decline in permeate flux. It appears that for optimal operation, the concentration of retentate should not exceed six times that of the raw wastewater. Under such conditions, the membrane was able to recover more than 85% of its initial performance after chemical cleaning. In contrast, during subsequent trials where the concentrate reached a 20-fold concentration, chemical cleaning proved less effective.

Furthermore, it is necessary to consider whether membranes with a molecular weight cut-off point (MWCO) of 4 kDa, as tested, are optimally selected for the intended application. The results indicate that while these membranes exhibit excellent contaminant separation performance, they are less favorable in terms of fouling propensity and permeate flow blockage. Studies conducted by W. Tomczak and M. Gryta using PES ultrafiltration membranes on wastewater with similar contaminant profiles originating from car wash facilities-characterized by high COD and elevated surfactant content-demonstrated that membranes with an MWCO of approximately 10 kDa are better suited for this purpose. Membranes with lower MWCO values were found to be more prone to fouling under these conditions [

28].

In the actual industrial system under analysis, the wastewater stream that is to be subjected to the pretreatment process has a flow rate of 3 m³/h. The production process operates continuously 24 hours a day, five days a week. For the investigated PES membrane, the permeate flux ranged from 140 to 180 L/m²·h. Therefore, to achieve the required permeate flow and ensure a functional water recovery system, a minimum active membrane area of 20 m² would be necessary, along with the use of at least two such modules to provide satisfactory system redundancy.

Comparing the performance results of the PCI ESP04 membranes with studies conducted by P. Woźniak and M. Gryta, where the same membrane was evaluated against membranes with higher MWCO values, it can be inferred that the use of a membrane with a higher MWCO, such as the FP100 membrane manufactured by PCI Membranes-made of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) with an MWCO of 100 kDa-could yield permeate of comparable quality at several times higher flux [

23].

Considering the application of the tested PES membrane for the construction of a closed-water recirculation system in the rubber hose washing process, it can be concluded that this process is highly effective in improving the visual quality of wastewater and demonstrating very good efficiency in the separation of chemical contaminants. However, to develop a fully efficient system, it is necessary to effectively mitigate membrane fouling. To this end, the ultrafiltration process should be preceded by preliminary wastewater treatment, such as sedimentation or prefiltration using, for example, string-wound or sand filters. Further research should focus on membranes with higher molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) values to evaluate their separation capabilities and confirm improved performance for this application. Furthermore, in future studies, the use of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), such as the Fenton reaction, applied to raw wastewater prior to ultrafiltration could be considered, as these may reduce membrane fouling and limit the occurrence of fouling phenomena [

29].

5. Conclusions

Modified PES membranes, type ESP04 from PCI Membranes, demonstrated high efficiency in the removal of turbidity from wastewater.

The obtained permeate exhibited a significant reduction in the concentration of the analyzed contaminants.

The membranes were prone to fouling and, after approximately six hours of filtration, their performance decreased markedly; this phenomenon could not be compensated for by increasing the operating pressure.

Membrane regeneration through chemical cleaning with alkaline agents only partially mitigated fouling, resulting in a permanent performance loss of approximately 30%.

For the wastewater studied, ultrafiltration tests should be repeated using membranes with a higher MWCO parameter, eg, FP100 with MWCO = 100 kDa.

More research is needed to assess the potential benefits of applying a preliminary wastewater pretreatment process prior to ultrafiltration, such as advanced oxidation processes (AOP).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; Validation, P.T. M.R.; formal analysis, S.K. and M.R.; investigation, S.K.; resources, P.T. ; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; supervision, P.T. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science under the 6th edition of the Industrial Ph.D. program, within the project entitled ‘Reduction of non-ionic surfactants (SPC) in industrial wastewater. Closed water loop exemplified by an industrial plant. ‘ Funding agreement no. DWD/6/0539/2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- A. Rahimpour, S.S. Madaeni, S. Mehdipour-Ataei, Synthesis of a novel poly(amide-imide) (PAI) and preparation and characterization of PAI blended polyethersulfone (PES) membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2008, 311, Issues 1-2, Pages 349-359. [CrossRef]

- N. Sazali, W. Norharyati, W. Salleh, N. A. H. Md Nordin, Z. Harun, A. F. Ismail. Matrimid-based carbon tubular membranes: The effect of the polymer composition. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2015, 132, Issue 33, 42394. [CrossRef]

- K. Hernandez, C. Muro, R. E. Ortega, S. Velazquez, F. Riera. Water recovery by treatment of food industry wastewater using membrane process. Environmental Technology 2021, 42, Issue 5, Pages 775-788. [CrossRef]

- R. Haas, R. Oitz, T. Grischek, P. Otter. AquaNES Project: Coupling Riverbank Filtration and Ultrafiltration in Drinking Water Treatment. Water 2019, 11, Pages 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Parisa Daraei, Sayed Siavash Madaeni, Negin Ghaemi, Mohammad Ali Khadivi, Bandar Astinchap, Rostam Moradian. Enhancing antifouling capability of PES membrane via mixing with various types of polymer modified multi-walled carbon nanotube. [CrossRef]

- A. Świerczyńska, J. Bohdziewicz, G. Kamińska, K. Wojciechowski. Influence of the type of membrane-forming polymer on the membrane fouling. Environment Protection Engineering 2016, 42, no. 2, Pages 197-210. [CrossRef]

- F. Meng, S. R. Chae, A. Drews, M. Kraume, H. S. Shin, F. Yang. Recent advances in membrane bioreactors (MBRs): membrane fouling and membrane material. Water Resorces 2009, 43, Pages 1489-1512. [CrossRef]

- S. Liang, K. Xiao, Y. Mo, X. Huang. A novel ZnO nanoparticle blended polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for anti-irreversible fouling. Journal of Membrane Science 2012, 394, Pages 184-192. [CrossRef]

- Gryta M.; Woźniak P. Polyethersulfone membrane fouling mitigation during ultrafiltration of wastewaters from car washes. Desalination 2024, 574, 117254. [CrossRef]

- E. Nurmalasari, H. Ulia, A. P. Ainia, A. K. Yahya, Y. Fahni. Modified Polyethersulfone (PES) Membran Methods to Improve Anti-fouling. Mini Review. Eksergi. Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Kimia, 2023, 20 (2), Pages 64-75. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, B. Van der Bruggen. The use of nanoparticles in polymeric and ceramic membrane structures: Review of manufacturing procedures and performance improvement for water treatment. Environmental Pollution 2010, 158, Issue 7, Pages 2335-2349. [CrossRef]

- Qian Li, Shunlong Pan, Xin Li, Chao Liu, Jiansheng Li, Xiuyun Sun, Jinyou Shen, Weiqing Han, Lianjun Wang. Hollow mesoporous silica spheres/polyethersulfone composite ultrafiltration membrane with enhanced antifouling property. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2015, 487, Pages 180-189. [CrossRef]

- Li Wang, Xiangju Song, Tao Wang, Shuzheng Wang, Zhining Wang, Congjie Gao. Fabrication and characterization of polyethersulfone/carbon nanotubes (PES/CNTs) based mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) for nanofiltration application. Applied Surface Science 2015, 330, Pages 118-125. [CrossRef]

- Sri Aprilia, Cut Meurah Rosnelly, Sri Ramadhani, Lia Novarina, Umi Fathanah, Fauzi M. Djuned dan Amri Amin. Characterization of Polyether Sulfone Membranes Filled with Activated Carbon. Jurnal Rekayasa Kimia dan Lingkungan 2018, 13 (1), Pages 82-93. [CrossRef]

- G. Kamińska. WWTP effluent treatment with ultrafiltration with different mixed matrix nanocomposite membranes. Comparison of performance and fouling behavior. Archives of Environmental Protection 2022, 48 (4), Pages 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Cigdem Balcik-Canbolat, Bart Van der Bruggen. Efficient removal of dyes from aqueous solution the potential of cellulose nanocrystals to enhance PES nanocomposite membranes. Cellulose 2020, 27, Pages 5255-5266. [CrossRef]

- Tutuk Djoko Kusworo, Qudratun, Dani Puji Utomo. Performance evaluation of double stage process using nano hybrid PES/SiO2-PES membrane and PES/ZnO-PES membranes for oily waste water treatment to clean water. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2017, 5, Issue 6, Pages 6077-6086. [CrossRef]

- R. Sathish Kumar, G. Arthanareeswaran. Nano-curcumin incorporated polyethersulfone membranes for enhanced anti-biofouling in treatment of sewage plant effluent. Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 94, Pages 258-269. [CrossRef]

- Bo Liang, Ye Yang, Junping Li. Research progress of water-based release agents. MATEC Web Conference 2022, 358, 01033. [CrossRef]

- Yang Mengqing, Li Lihong, Zhu Zhiqiang, Ma Haiyan. Research progress on eco-friendly rubber release agents. Colloid and Polymer Science 2025, 303, Pages 163-174. [CrossRef]

- I. Ullah, M. N. Naser, A. A. Zaidi, M. Kumar, U. Rasool, B. Kim. Research hotspots and development trends in the rubber industry wastewater treatment: a quantitative analysis of literature. Journal of Rubber Research 2023, 26, Pages 249-260. [CrossRef]

- Performance Fluid. Safety data sheet. Rheolase 487LG. 2025, Revision 1.0,21.10.2021, Available online: www.performancefluids.co.uk (accessed on 20.03.2025).

- Woźniak P., Gryta, M. Application of Polymeric Tubular Ultrafiltration Membranes for Separation of Car Wash Wastewater. Membranes 2024, 14, 210.

- PCI Membranes. Membrane technical datasheet. PCI ESP04. 2019, Available online: https://www.pcimembranes.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/PCI_B1_Series.pdf, (accessed on 20.03.2025).

- Ecolab. Safety datasheet. Ecolab P3 Ultrasil 02 2023, Available online: https://assets.pim.ecolab.com/media/Original/10062/PL-PL-115941E-ULTRASIL (accessed on 20.03.2025).

- Ecolab. Safety datasheet. Ecolab P3 Ultrasil 11 2023, Available online: https://assets.pim.ecolab.com/media/Original/10062/PL-PL-114224E-ULTRASIL (acessed on 20.03.2025).

- Woźniak P., Gryta, M., Mozia S. Effects of Alkaline Cleaning Agents on the Long-Term Performance and Aging of Polyethersulfone Ultrafiltration Membranes Applied for Treatment of Car Wash Wastewater. Membranes 2024, 14, 122. [CrossRef]

- Tomczak W., Gryta, The Application of Polyethersulfone Ultrafiltration Membranes for Separation of Car Wash Wastewaters: Experiments and Modelling. Membranes 2023, 13, 321. [CrossRef]

- M. Kowalczyk, T. Kamizela, K. Parkinta, M. Milczarek. Zastosowanie reakcji Fentona w technologii osadów ściekowych. Zeszyty Naukowe, Uniwersytet Zielonogórski 2011, 21, Pages 98-112.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).