Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Psychological Factors in Metabolic Aging [3,4,5,6,7]

2.1. Stress and HPA Axis Dysregulation

- Cortisol Overload

- Metabolic Consequences

2.2. Depression and Behavioral Inactivity

- Mood Disorders and Metabolism

- Impact on Physical Activity and Muscle Loss

- Implications for Aging

2.3. Sleep Disturbances and Circadian Misalignment

- Sleep and Hormonal Regulation of Metabolism

- Ghrelin, which increases hunger, is up following inadequate sleep, while leptin, which inhibits appetite and encourages energy expenditure, is decreased during sleep deprivation.

- Circadian Misalignment and Aging

- Unusual sleep-wake patterns

- Exposure to evening light (from screens or artificial light)

- Sleep, Mood, and Metabolic Vicious Cycle

- Implications for Aging Populations

3. Exercise as a Psychometabolic Intervention [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]

3.1. Neurochemical and Mood Benefits

- Serotonin, which controls appetite, mood, and sleep.

- Dopamine and norepinephrine, which enhance mental clarity, motivation, and attentiveness.

3.2. Metabolic Resilience Through Physical Activity

- Increased Insulin Sensitivity: Exercise increases the absorption of glucose into muscle cells, which lowers blood sugar levels and improves insulin’s effects.

- Increased Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Exercise, particularly endurance training, enhances the quantity and functionality of mitochondria, the cell’s energy factories, which improves energy metabolism in general.

- Fat Mobilisation and Redistribution: Exercise, even in the absence of notable weight changes, lowers dangerous visceral fat and encourages a healthier body composition.

3.3. Integration of Psychological and Physical Health

- Exercise that increases metabolism also increases energy, physical function, and self-efficacy, all of which contribute to improved emotional health.

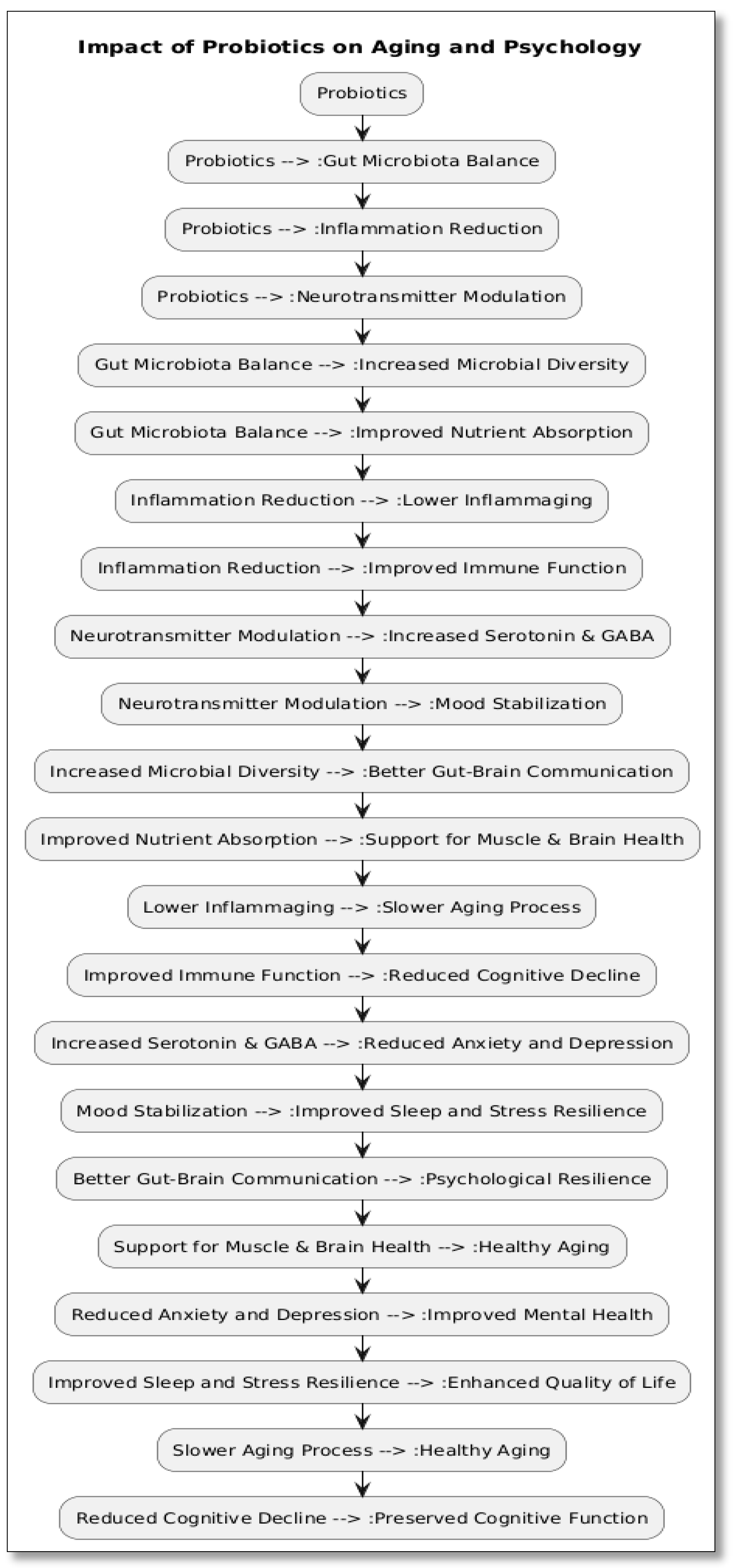

4. Gut-Brain-Metabolism Axis: The Role of Prebiotics and Probiotics [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]

4.1. Gut Microbiota and Neuroendocrine Function

- Serotonin (5-HT): The gut produces over 90% of the body’s serotonin. Depression and anxiety may be exacerbated by dysbiosis, which lowers serotonin availability.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA): This inhibitory neurotransmitter, which helps to relax the nervous system, is produced by some strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): These molecules, such as butyrate, are produced when microbes ferment prebiotic fibres. They help maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier and have anti-inflammatory properties that benefit the body and brain.

4.2. Probiotics for Psychological and Metabolic Health

- Better glucose metabolism

- Improved nutritional absorption (such as vitamin D, B12, and magnesium); • Decreased body fat buildup; • Improved immunological modulation, particularly in older persons with weakened defences

4.3. Prebiotics and Stress Modulation

4.4. Potential for Sarcopenia and Metabolic Syndrome Prevention

- Improve the absorption of amino acids needed for the synthesis of muscle proteins;

- Reduce inflammation in muscles through systemic immune control.

- Enhance the nutritional status of elderly, fragile populations

5. Synergistic Strategies for Healthy Aging [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]

| Factor | Impact on Metabolism | Intervention |

| Chronic Stress | ↑ Cortisol → ↑ Fat storage, ↓ Muscle synthesis | Exercise, Meditation, Probiotics |

| Depression | ↓ Activity, ↑ Inflammation, Disrupted appetite | Psychotherapy, Physical Activity, Probiotics |

| Sleep Disturbances | Hormonal imbalance → ↑ Hunger, ↓ Insulin sensitivity | Sleep hygiene, Melatonin, Pre/Probiotics |

| Gut Dysbiosis | ↑ Inflammation, ↓ Neurotransmitter production | Prebiotics, Probiotics, Dietary Fiber |

| Social Isolation (Psychosocial) | ↓ Activity, ↑ Inflammatory markers | Group Exercise, Community Support |

6. Conclusion

References

- Munot N, Kandekar U, Rikame C, Patil A, Sengupta P, Urooj S, et al. Improved mucoadhesion, permeation and in vitro anticancer potential of synthesized thiolated acacia and karaya gum combination: a systematic study. Molecules. 2022;27:6829. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munot N, Kandekar U, Giram PS, Khot K, Patil A, Cavalu S. A comparative study of quercetin-loaded nanocochleates and liposomes: formulation, characterization, assessment of degradation and in vitro anticancer potential. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikyam HK, Tripathi P, Patil SB, Lamichhane J, Chaitanya M, Patil AR. Extraction, purification, and quantification of hesperidin from the immature Citrus grandis/maxima fruit Nepal cultivar. Asian J Nat Prod Biochem. 2022;20. [CrossRef]

- Patil A, Munot N, Patwekar M, Patwekar F, Ahmad I, Alraey Y, et al. Encapsulation of lactic acid bacteria by lyophilisation with its effects on viability and adhesion properties. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalawade AS, Gurav RV, Patil AR, Patwekar M, Patwekar F. A comprehensive review on morphological, genetic and phytochemical diversity, breeding and bioprospecting studies of genus Chlorophytum Ker Gawl. from India. Trends Phytochem Res. 2022;6(1):19–45.

- Patil KG, Balkundhi S, Joshi H, Ghewade G. Mehsana buffalo milk as prebiotics for growth of Lactobacillus. Int J Pharm Pharm Res. 2011;1(1):114–7.

- Das N, Ray N, Patil AR, Saini SS, Waghmode B, Ghosh C, et al. Inhibitory effect of selected Indian honey on colon cancer cell growth by inducing apoptosis and targeting the β-catenin/Wnt pathway. Food Funct. 2022;13:8283–303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil MJ, Mali V. The diverse cytotoxicity evaluation of Lactobacillus discovered from sheep milk. Acta Sci Pharm Sci. 2021;5(12):69–70.

- Abhinandan P, John D. Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus plantarum with the cell adhesion properties. J Glob Pharma Technol. 2020;10(12):1–6.

- Patil A, Pawar S, Disouza J. Granules of unistrain Lactobacillus as nutraceutical antioxidant agent. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2018;9(4):1594–9.

- Patil A, Mali V, Patil R. Banana fibers camouflaging as a gut worm in a 6-month-old infant. Iberoam J Med. 2020;2:245–7. [CrossRef]

- Munot NM, Shinde YD, Shah P, Patil A, Patil SB, Bhinge SD. Formulation and evaluation of chitosan-PLGA biocomposite scaffolds incorporated with quercetin liposomes made by QbD approach for improved healing of oral lesions. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021;24(6):147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil A. Psychology in the age of technology dependence and the mobile dilemma. Preprints.org. 2023;2023070101.

- Patil A, Kotekar D, Chavan G. Knowing the mechanisms: how probiotics affect the development and progression of cancer. Preprints.org. 2023;2023070243.

- Kim CS, Jung MH, Shin DM. Probiotic supplementation has sex-dependent effects on immune responses in association with the gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Nutr Res Pract. 2023;17(5):883–898. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li G, Li W, Song B, et al. Differences in the gut microbiome of women with and without hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a case-control study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim CS, Jung MH, Shin DM. Probiotic supplementation has sex-dependent effects on immune responses in association with the gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Nutr Res Pract. 2023;17(5):883–898. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li G, Li W, Song B, et al. Differences in the gut microbiome of women with and without hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a case-control study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingade JA, Padalkar NS, Shin JH, Kim YH, Park TJ, Park JP, Patil AR. Electrostatically assembled maghemite nanoparticles-Lactobacillus plantarum: A novel hybrid for enhanced antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antibiofilm efficacy. Bioresour Technol. 2025;430:132538. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikyam HK, Joshi SK, Patil SB, Vakadi S, Patil AR. Steroidal glycosides from Mallotus philippensis induce apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells via MTT and DAPI assays. Asian J Nat Prod Biochem. 2025;23(1).

- Wang J, Yuan F, Kendre M, He Z, Dong S, Patil A, Padvi K. Rational design of allosteric inhibitors targeting C797S mutant EGFR in NSCLC: an integrative in silico and in-vitro study. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1590779. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakate MK, Wategaonkar SB, Zambare DN, Shembade UV, Moholkar AV, et al. Dual extracellular activities of cobalt and zinc oxides nanoparticles mediated by Carica papaya latex: Assessment of antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activities. Inorg Chem Commun. 2025;114538. [CrossRef]

- Patil A, Singh N, Patwekar M, Patwekar F, Patil A, Gupta JK, Elumalai S, et al. AI-driven insights into the microbiota: Figuring out the mysterious world of the gut. Intell Pharm. 2025;3(1):46–52. [CrossRef]

- Manikyam HK, Joshi SK, Patil SB, Patil AR, Ponnuru VS. Free radical-induced inflammatory responses activate PPAR-γ and TNF-α feedback loops, driving HIF-α mediated metastasis in HCC: In silico approach of natural compounds. Univ Libr Biol Sci. 2025;2(1):1.

- Bhinge SD, Jadhav S, Lade P, Bhutkar MA, Gurav S, Jadhav N, Patil A, et al. Biogenic nanotransferosomal vesicular system of Clerodendrum serratum L. for skin cancer therapy: Formulation, characterization, and efficacy evaluation. Future J Pharm Sci. 2025;11(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Kareppa MS, Jangme CM, Patil AR. Phytochemical investigation and HPTLC screening of Tinospora cordifolia leaf extract. J Neonatal Surg. 2025;14(24s).

- Wang L, Xu Z, Bains A, Ali N, Shang Z, Patil A, Patil S. Exploring anticancer potential of Lactobacillus strains: Insights into cytotoxicity and apoptotic mechanisms on HCT 115 cancer cells. Biologics: Targets Ther. 2024:285–295. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikyam HK, Joshi SK, Patil SB, Patil AR. A review on cancer cell metabolism of fats: Insights into altered lipid homeostasis. Dis Res. 2025;4(2):97–107. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).