1. Introduction

The field of nanomaterials and nanotechnology holds significant importance in contemporary scientific investigations. These materials find applications across various aspects of life, while their practical performance is determined by their nanostructural architecture and the constituent materials.

The partially filled d-orbitals of transition metal ions and the high electronegativity of oxygen atoms in transition metal oxides (TMOs) account for their intriguing and diverse properties, making them a widely investigated class of materials. These unique electronic structures are manifested in a range of phenomena, including colossal magnetoresistance (CMR), high-temperature superconductivity, electrocatalytic and photocatalytic activity, as well as ferromagnetic, ferroelectric, ferroelastic, thermoelectric, multiferroic, and gas-sensing capabilities [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The nanomaterials are a class of materials characterized by having at least one dimension in the range of 1 to 100 nm. Based on the number of nanosized dimensions, the architecture of nanomaterials can be categorized into four main groups: 0D (nanoparticles, quantum dots); 1D (nanorods, nanowires, nanofibers); 2D (nanosheets, graphene, other 2D materials); and 3D (nanospheres, nanoprisms, nanotubes, nanoporous materials). Two primary approaches exist for the production of diverse nanomaterials: top-down and bottom-up. The top-down approach is a subtractive method involving the breakdown of a bulk material into nanomaterials (e.g., nanolithography, mechanical milling, laser ablation, sputtering, electron explosion, arc discharge, electrospinning, and thermal decomposition). In contrast, the bottom-up approach entails the assembly of nanostructures from atomic or molecular precursors through methods, such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), atomic layer deposition (ALD), sol-gel processing, spin coating, and pyrolysis [

7,

8,

9].

Nanotubular fibers represent a promising class of three-dimensional (3D) nanomaterials for applications in batteries, catalysis, and gas sensing, primarily due to their high specific surface area. Several fabrication methods have been developed, among which electrospinning is particularly versatile. This technique encompasses configurations, such as single-nozzle, coaxial, triaxial, microfluidic, and emulsion electrospinning, along with hybrid approaches that integrate electrospinning and atomic layer deposition [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Numerous research groups have utilized a combination of electrospinning and ALD to fabricate various fiber structures. In the conventional approach, a low-temperature ALD process is employed following electrospinning to coat the polymer fibers with different thin films, thereby preventing polymer degradation. However, at these reduced temperatures, some deposited films exhibit non-ideal, non-self-limiting growth behaviour, as the process often operates outside the optimal ALD temperature window. Furthermore, in certain cases, post-deposition annealing of such structures can induce the Kirkendall effect, resulting in the disruption of the microtubular morphology [

15].

To overcome these challenges, we adopted a modified approach. First, the polymer fibers were coated with Al₂O₃ via low-temperature ALD. Owing to its thermal and chemical stability, Al₂O₃ acts as an inert structural matrix. Subsequent thermal annealing was performed to obtain hollow Al₂O₃ fibers. This sequence enabled the final deposition of desired functional active films by thermal ALD, ensuring growth within their respective optimal ALD windows.

In this study, two-layered hollow submicron fibers were produced by combining electrospinning and ALD. The inner shell consisted of amorphous Al₂O₃, while the outer shell was ZnO doped with Co, Fe, or Ni. The morphology and elemental composition of the resulting hollow double-shell fibers were investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy. The crystalline structure was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the surface chemical states and elemental composition were determined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis.

3. Results and Discussions

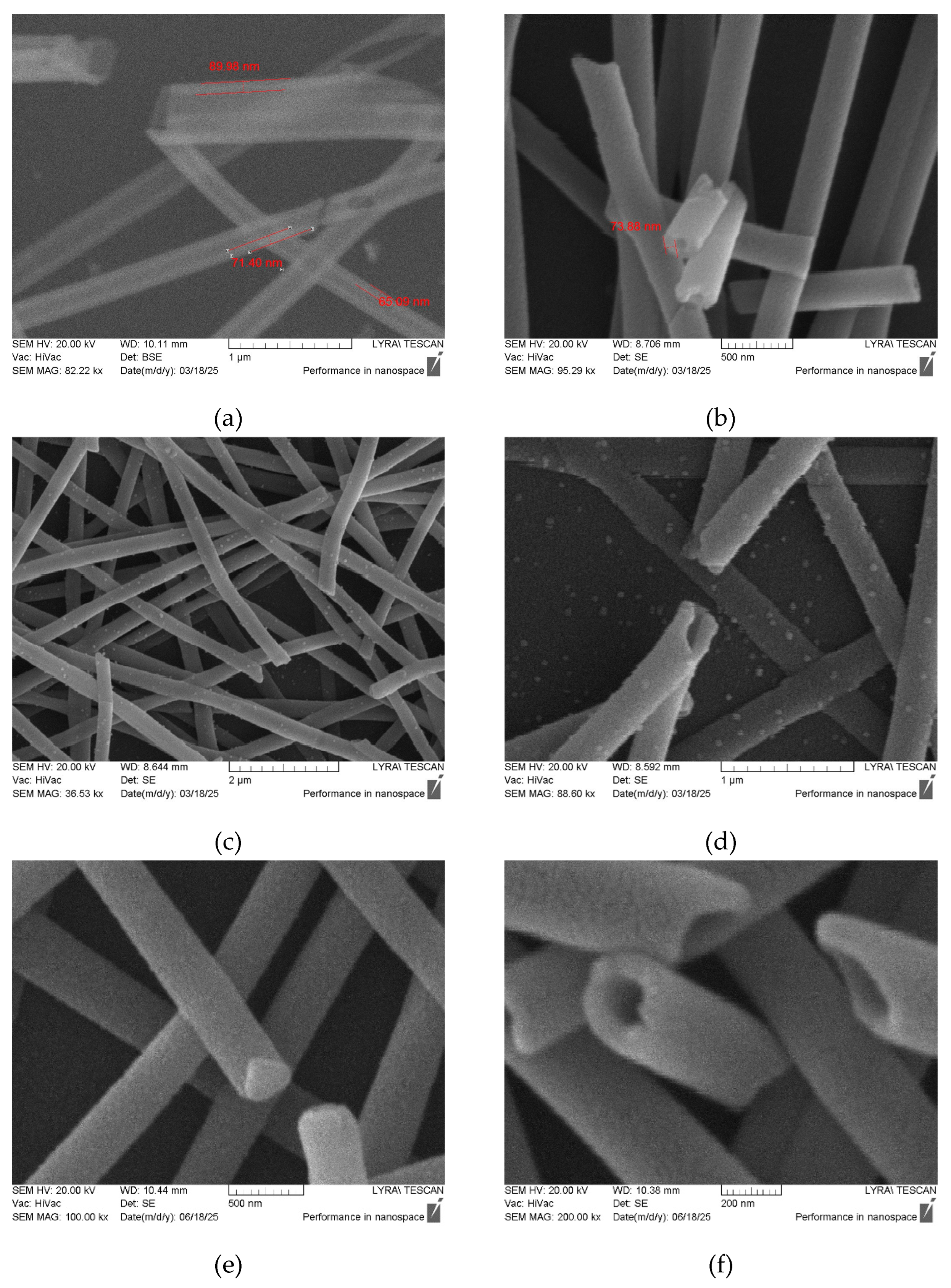

High-quality double-layered hollow ZnO:TM/ALO fibers were successfully synthesized; they exhibited uniform distribution, well-defined shapes, and smooth, defect-free surfaces (

Figure 2). The fiber thickness and fiber-wall thickness were directly determined from SEM images, with these findings corroborated by ellipsometry measurements on films deposited on p-Si(100) reference substrates. (the ellipsometry consistently showed 2-3 nm thinner films, likely due to a slower initial reaction rate on Si compared to the HO-rich PVA surface.)

The outer fiber diameters varied from 310 to 420 nm depending on the ALD regime (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Due to shrinkage occurring during the ALD and annealing processes, in some cases the resulting ZnO/Al₂O₃ fibers possessed smaller diameters than the initial pure PVA fibers [

15]. Notably, the pure ZnO/ALO and ZnO:Ni/ALO fibers in both series (s1 and s2) displayed larger diameters. The increased diameter in ZnO/ALO-s1 is attributed to the higher number of ZnO ALD cycles compared to its doped counterparts (

Table 1). Significantly, the ZnO:Ni/ALO-s1 was the only sample in its series where nickel (Ni) was detected via EDX and XPS analysis (see below). This observation suggests a faster reaction kinetic for nickelocene compared to ferrocene and cobaltocene within this specific ALD regime. ALD regime for series 2 is distinguished by more TMO cycles and higher precursor and reactor temperatures. Increasing the temperatures accelerates the kinetic reaction of metallocenes and ozone and, therefore, Ni and Fe dopants are detected in this series. On the other hand, the higher temperature reduces the ZnO growth rate, since it is moved outside the ALD window [

16,

17,

18,

19].

The thickness of the fiber walls, i.e., the ZnO:TM/ALO films, was determined from SEM images (

Figure 3,

Table 2) as well as from ellipsometry measurements performed on the same films deposited on p-Si(100) reference substrates. Both methods yielded comparable wall thicknesses between 60 to 140 nm. The wall thickness variation within each series is attributed to differences in the initial growth rate.

It should be noted that the Ni-doped ZnO fibers exhibit a clearly visible grain structure with mean grain diameters of approximately 50 nm (

Figure 3 (c)-(e)). Furthermore, in some samples, Series 2, clogged fibers were observed (

Figure 3(e)). This is attributed to the non-self-limiting ALD regime in Series 2, which results in a mixed CVD-ALD growth for ZnO and, consequently, the occlusion of some hollow fibers.

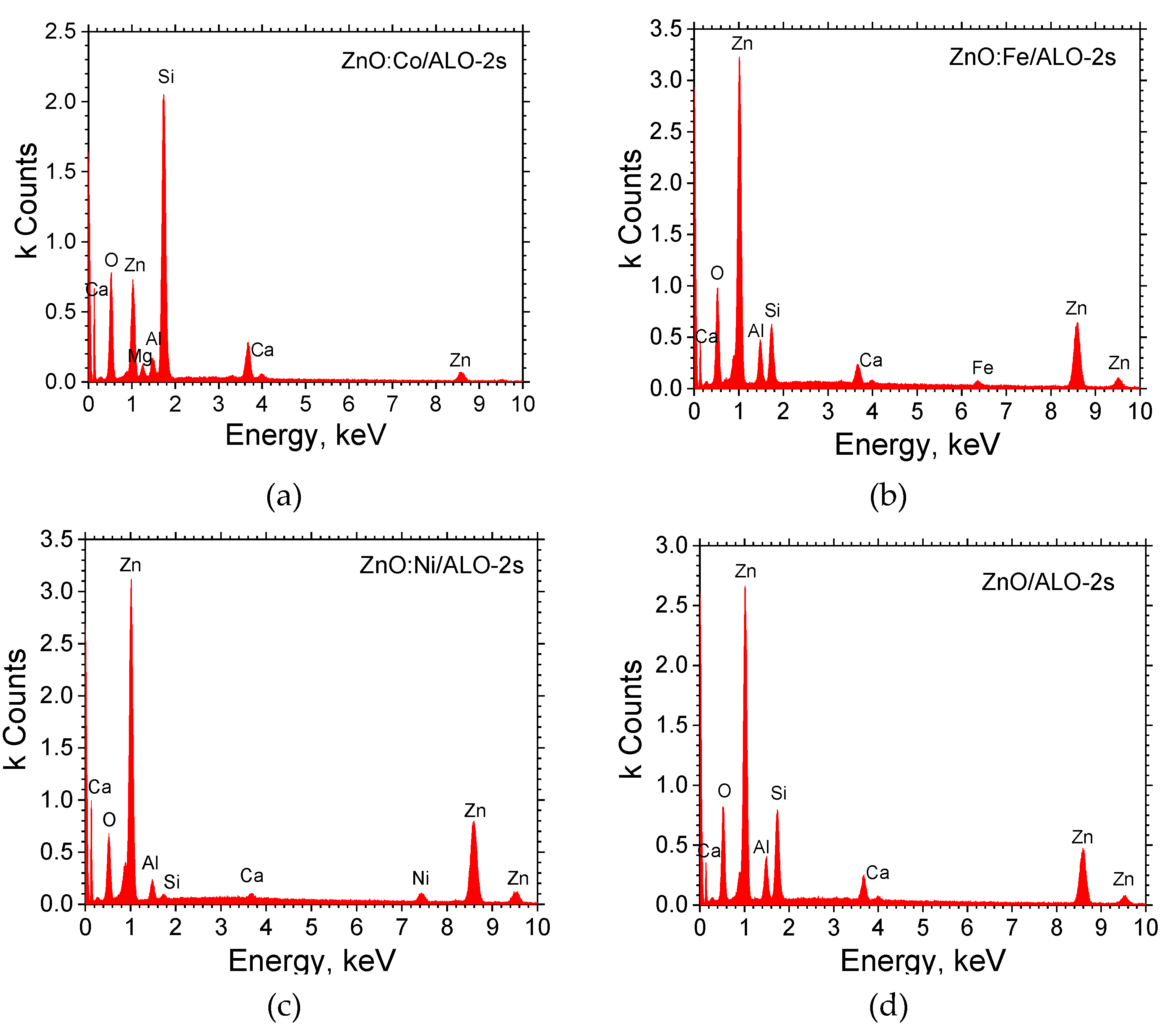

Figure 4 presents an EDX analysis of ZnO:TM/ALO-s2 hollow fibers fabricated on glass substrates. In all samples, zinc (Zn) and aluminum (Al), originating from the ZnO/Al₂O₃ fibers, are clearly visible. Given the fibrous mesh structure, elements from the underlying glass substrate, such as calcium (Ca), silicon (Si), and magnesium (Mg), are also detectable. For the doped fibers, nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe) elements are clearly observed. However, cobalt (Co) could not be detected in either series, which may be attributed to its concentration falling below the detection limit of the analysis.

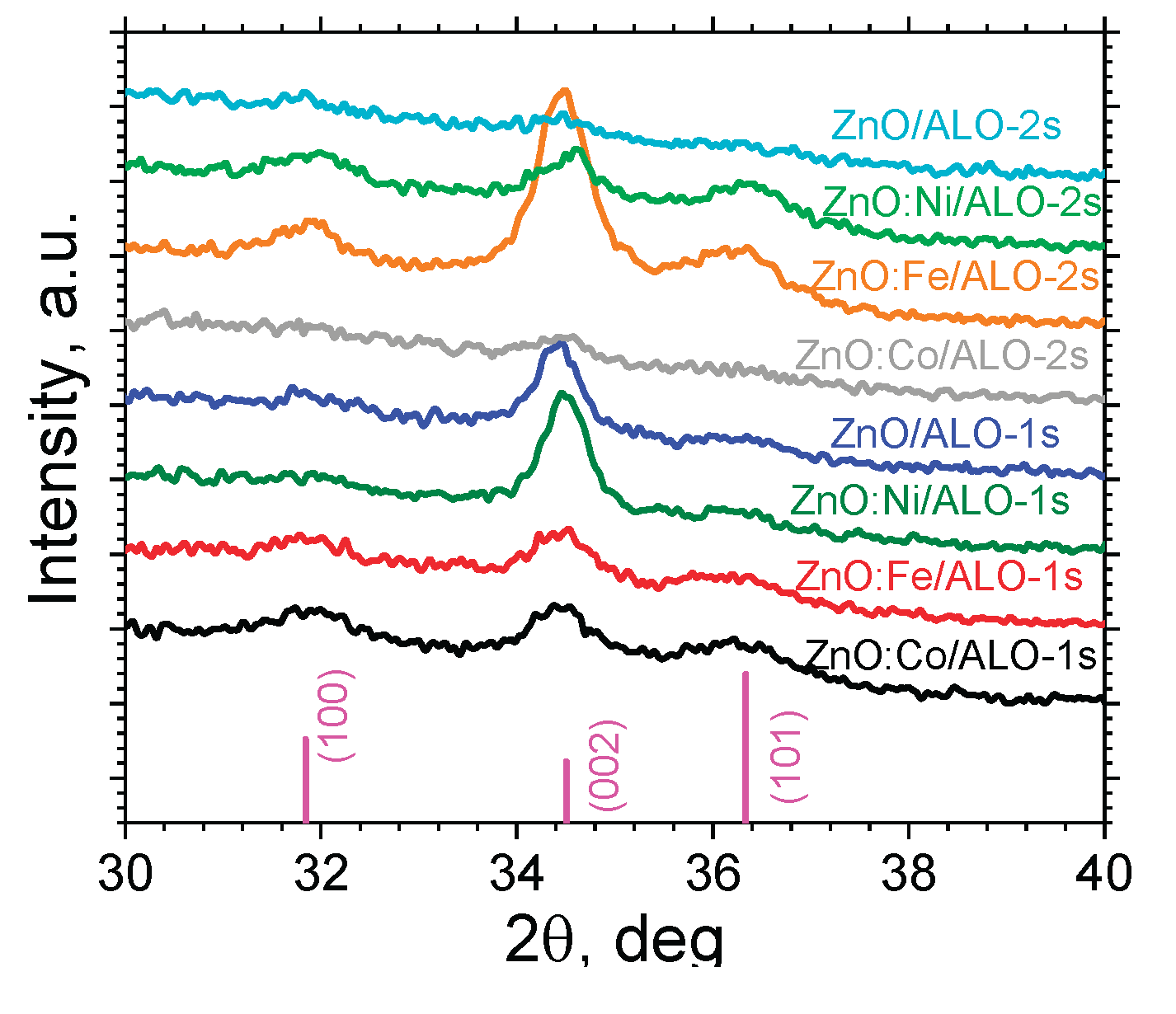

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses shown in

Figure 5 revealed a polycrystalline hexagonal phase with a wurtzite-type structure for the ZnO:TM top shell of the hollow ZnO:TM/ALO fibers obtained.

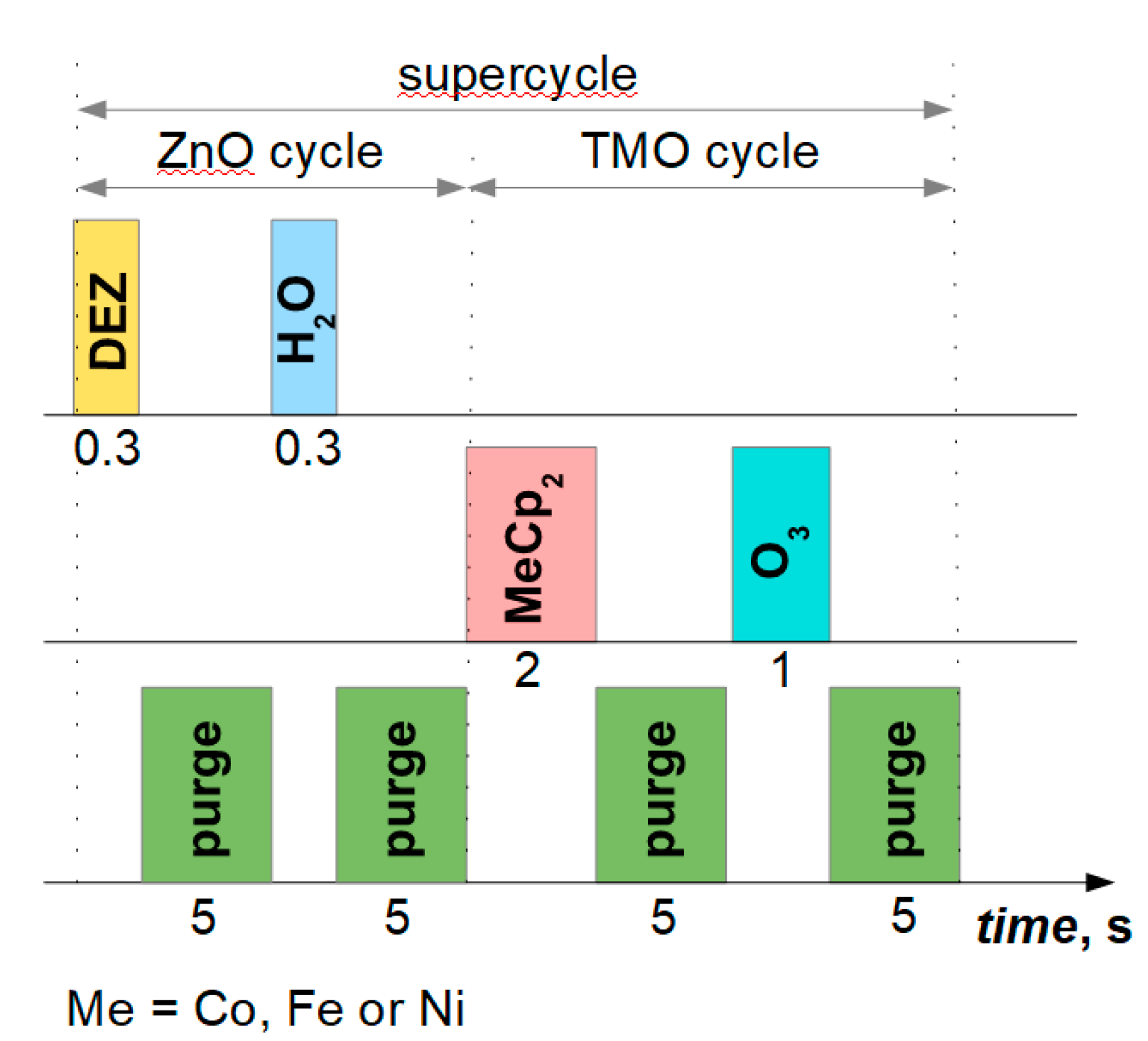

Table 3 summarizes the corresponding ZnO crystallite sizes. During ALD, sequential layers of ZnO and TMO were deposited. This growth mechanism, which depends on the reactor temperature (

Figure 1), significantly influences the nanostructure of the resulting films. Pure and Ni-doped ZnO samples from Series 1 exhibit a strong, predominantly

c-axis-oriented crystal structure and the largest crystallite sizes. Under regime 1, a reactor temperature of 200 °C provides an indispensable ALD window, resulting in relatively smooth and conformal ZnO films. Conversely, at an elevated temperature (230 ℃), which is outside the optimal ALD window for ZnO, the growth mechanism transitions from pure ALD to a mixed CVD-ALD regime. This transition results in highly uneven coatings with decreased ZnO crystallinity – the ZnO/ALO and ZnO:Co/ALO films reveal no significant crystallization. On such surfaces, an increased density of initial growth points leads to a larger number of crystallites but, simultaneously, a reduced overall size. For the Ni-doped ZnO fiber structures, continuous nickel oxide sublayers were obtained in both ALD regimes (as observed in the XPS analysis below,

Figure 8), which slightly affected the crystallographic orientation and size of the crystallites. At lower deposition temperatures, in the Co- and Fe-doped ZnO fiber structures, the reaction between metallocene and ozone proceeds very slowly or is even absent, leading to the formation of numerous defects that impair the crystal structure. As the temperature is raised, the reaction of ferrocene and ozone accelerates, enabling the formation of iron oxide sublayers and a corresponding increase in crystallite sizes. In these specific structures, an increase in the

ab-oriented growth of ZnO is observed.

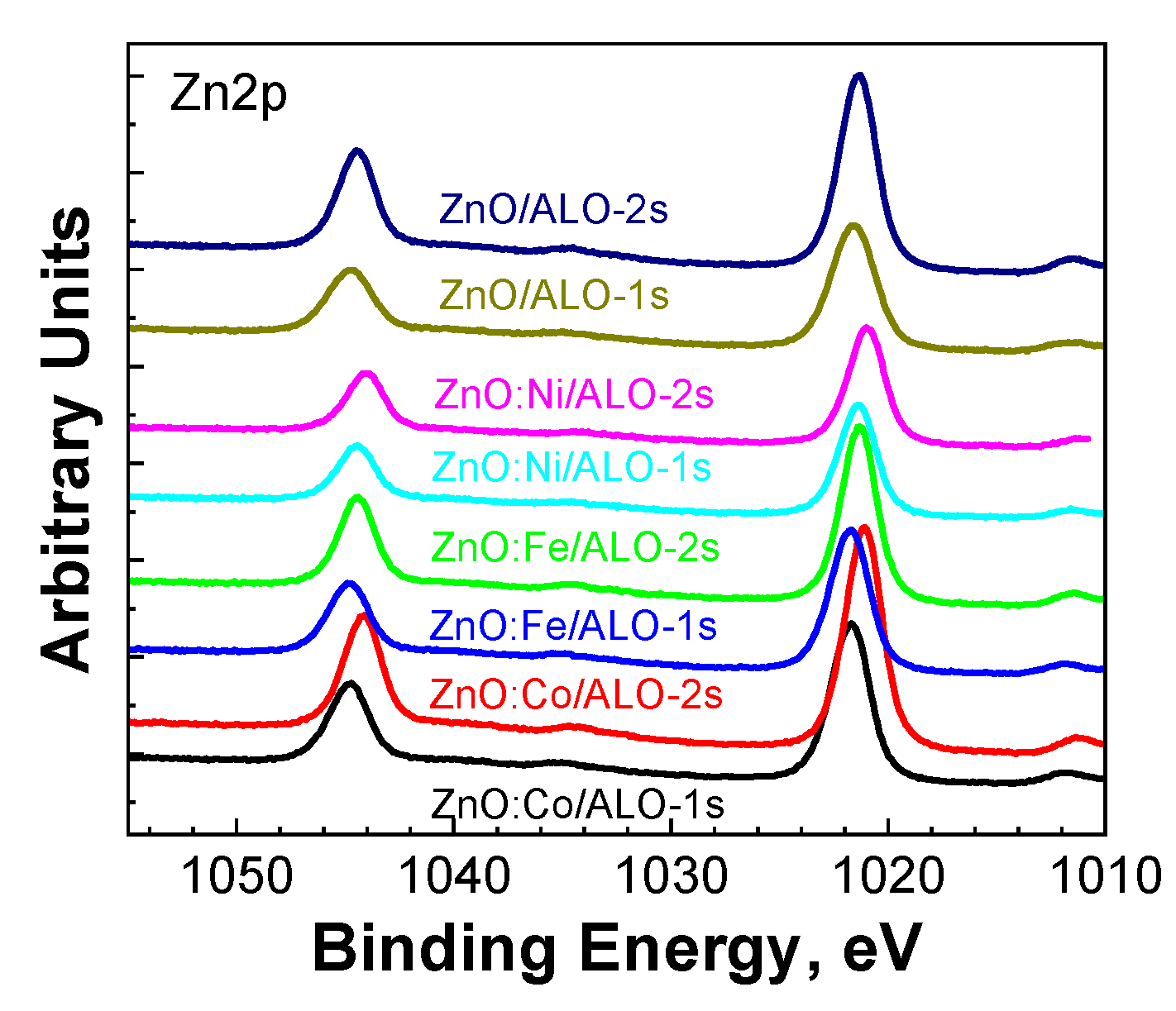

The XPS analysis detected the presence of C1s, O1s, and Zn2p signals on the surface of the ZnO:TM/ALO fiber structures. No Al2p signal was detected, primarily because XPS is a surface-sensitive technique with a typical X-ray penetration depth of only 3-5 nm. The observed C1s signal is attributed solely to surface contamination [

15]. Notably, only nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe) were detected as doping elements (further explanation provided below). In the Zn2p region, zinc appeared as a characteristic doublet, Zn2p

3/2 and Zn2p

1/2, with a spin-orbit splitting of 23.1 eV, consistent with ZnO (

Figure 6).

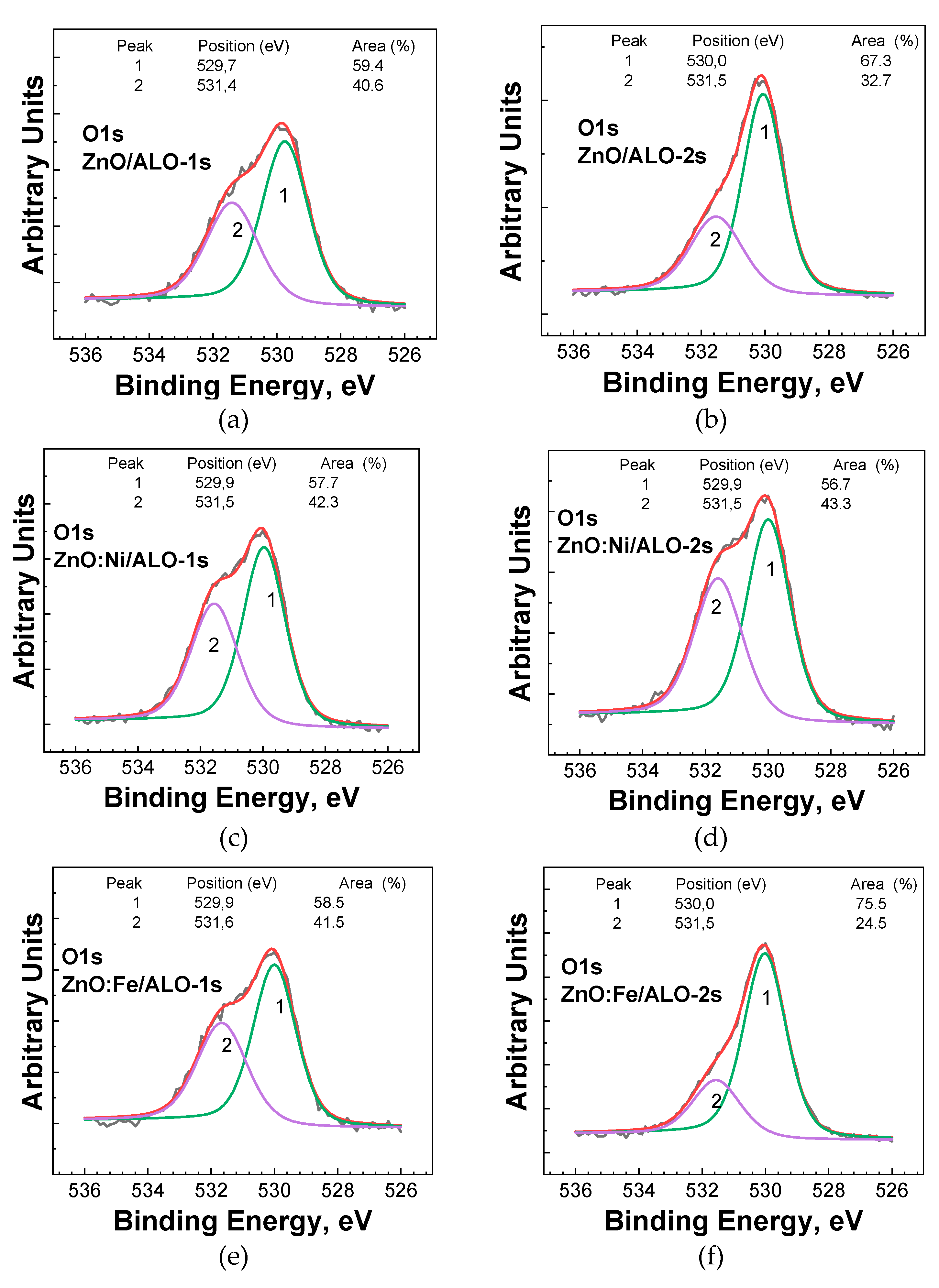

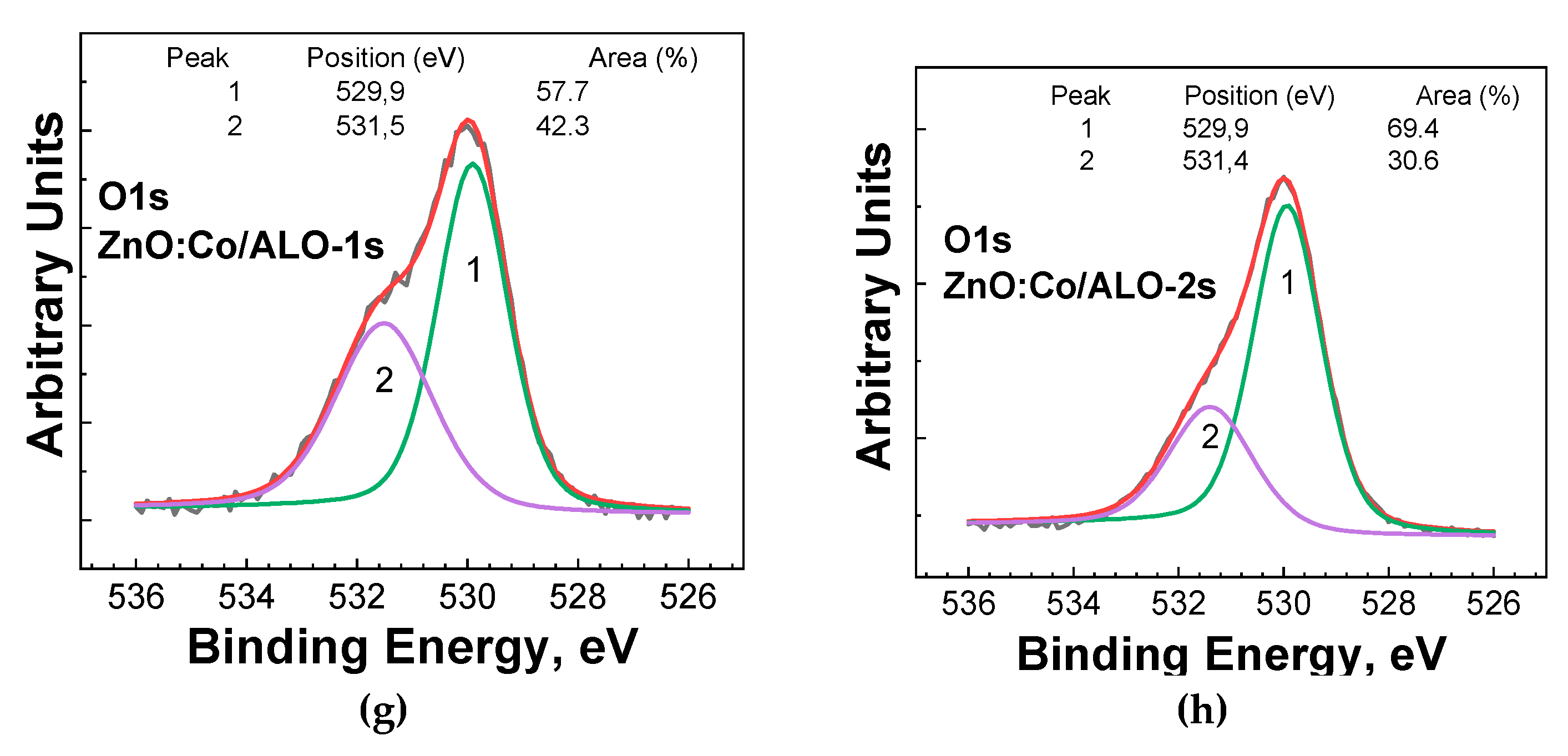

The O1s photoelectron line, centered at approximately 530.0 eV, is characteristic of oxygen within metal oxides. A smaller shoulder at the higher binding energy of 531.5 eV was consistently observed across all studied samples (

Figure 7), which is attributed to the formation of oxygen vacancies in the ZnO lattice [

20]. Consequently, the O1s photoelectron spectra provide valuable insights into the changes occurring in ZnO after doping with Co, Fe, or Ni. For ZnO doped with Co, Fe, and Ni at a lower ALD deposition temperature (Series 1), a slight increase in the oxygen vacancy formation was observed compared to the pure ZnO fibers deposited under the same conditions. At this deposition temperature, only Ni was identifiable as a dopant in the Ni2p region. The fibers deposited at higher temperatures exhibited a lower concentration of oxygen vacancies. Doping pure ZnO with Co, Fe, and Ni again resulted in modifications in the number of oxygen vacancies. Specifically, Co and Fe doping of ZnO reduced the oxygen vacancies, while Ni doping caused an increase. It's important to note that in this higher temperature ALD regime (Series 2), only Fe and Ni were detected on the surface of the studied fibers. Overall, ZnO and Co, Fe, and Ni-doped ZnO deposited at higher temperatures and with more cycles exhibited a lower number of oxygen vacancies than those deposited at lower temperatures and with fewer cycles.

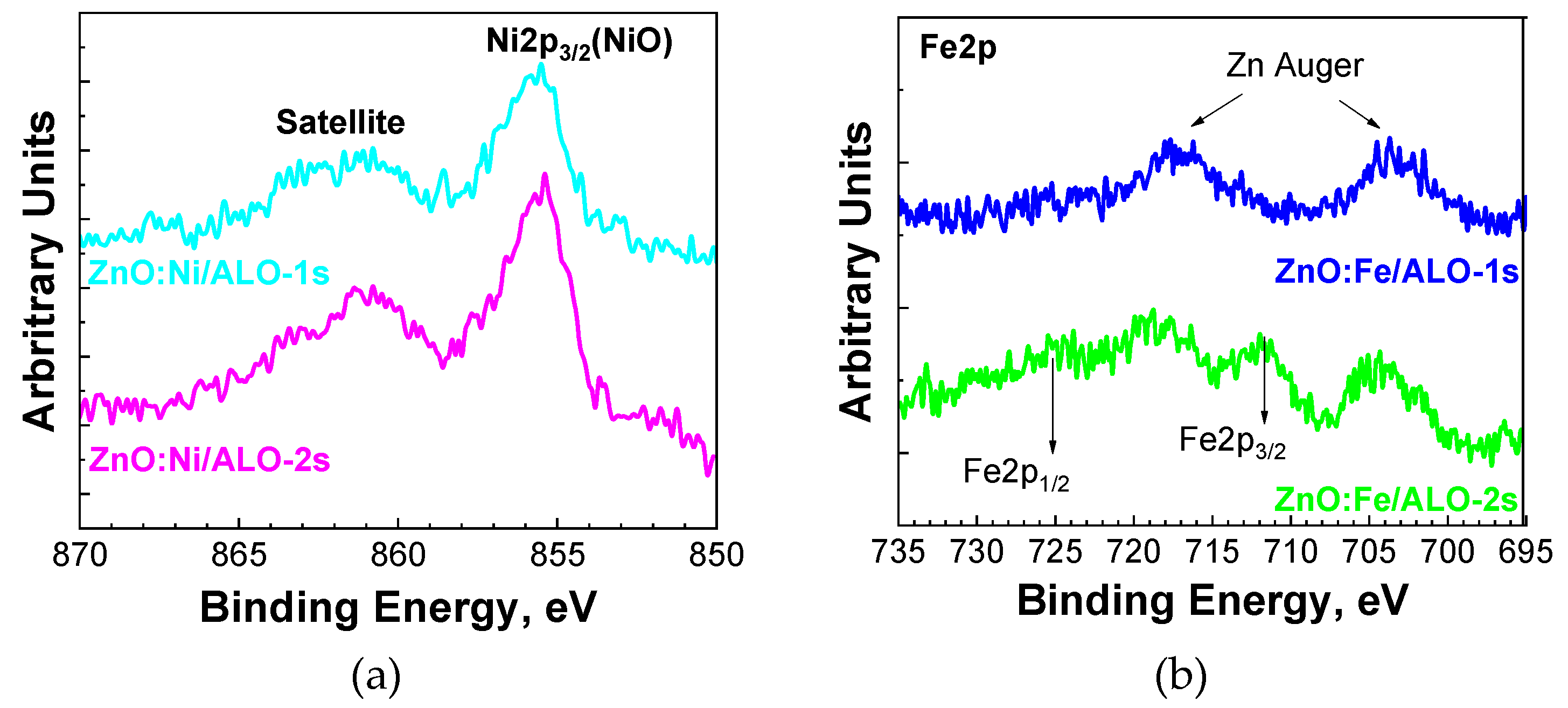

The Ni2p core-level spectra for both deposition temperatures show nickel in a Ni²⁺ oxidation state around 855.5 eV consistent with the presence of NiO or Ni(OH)₂ (

Figure 8a) [

21]. Conversely, iron (Fe) was detected only in the sample prepared at the higher deposition temperature (Series 2). The Fe2p signal overlaps significantly with the Zn Auger peaks (

Figure 8b), making the precise determination of the Fe2p peak positions challenging. Nevertheless, the Fe2p

3/2 peak is discernible between the Zn Auger peaks at approximately 712 eV for ZnO:Fe/ALO-2s fibers. Due to the close binding energies of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ oxidation states in various iron oxides (Fe₂O₃, Fe₃O₄, FeO, and FeO(OH)) [

22] and the overlap observed, identifying precisely the specific type of iron oxide in this study proved difficult.

Figure 8.

XPS of Ni2p3/2 (a) and Fe2p (b) of ZnO:TM/ALO fibers.

Figure 8.

XPS of Ni2p3/2 (a) and Fe2p (b) of ZnO:TM/ALO fibers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.B. and B.G.; methodology, B.S.B., B.G., K.S., N.S., K.B., V.M., L.S., D.S. and A.P.; validation, B.S.B. and B.G.; formal analysis, B.S.B. and B.G., investigation, B.S.B., B.G., I.A., P.T. (Peter Tzvetkov), K.S., N.S., K.B., V.M., L.S., P.T. (Penka Terziyska), D.S. and A.P.; resources, B.S.B.; data curation, B.S.B. and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.B. and B.G.; writing—review and editing, B.S.B., B.G., I.A., P.T. (Peter Tzvetkov), and A.P.; visualization, B.S.B. and B.G.; supervision, B.S.B.; project administration, B.S.B.; funding acquisition, B.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.