Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Study Population

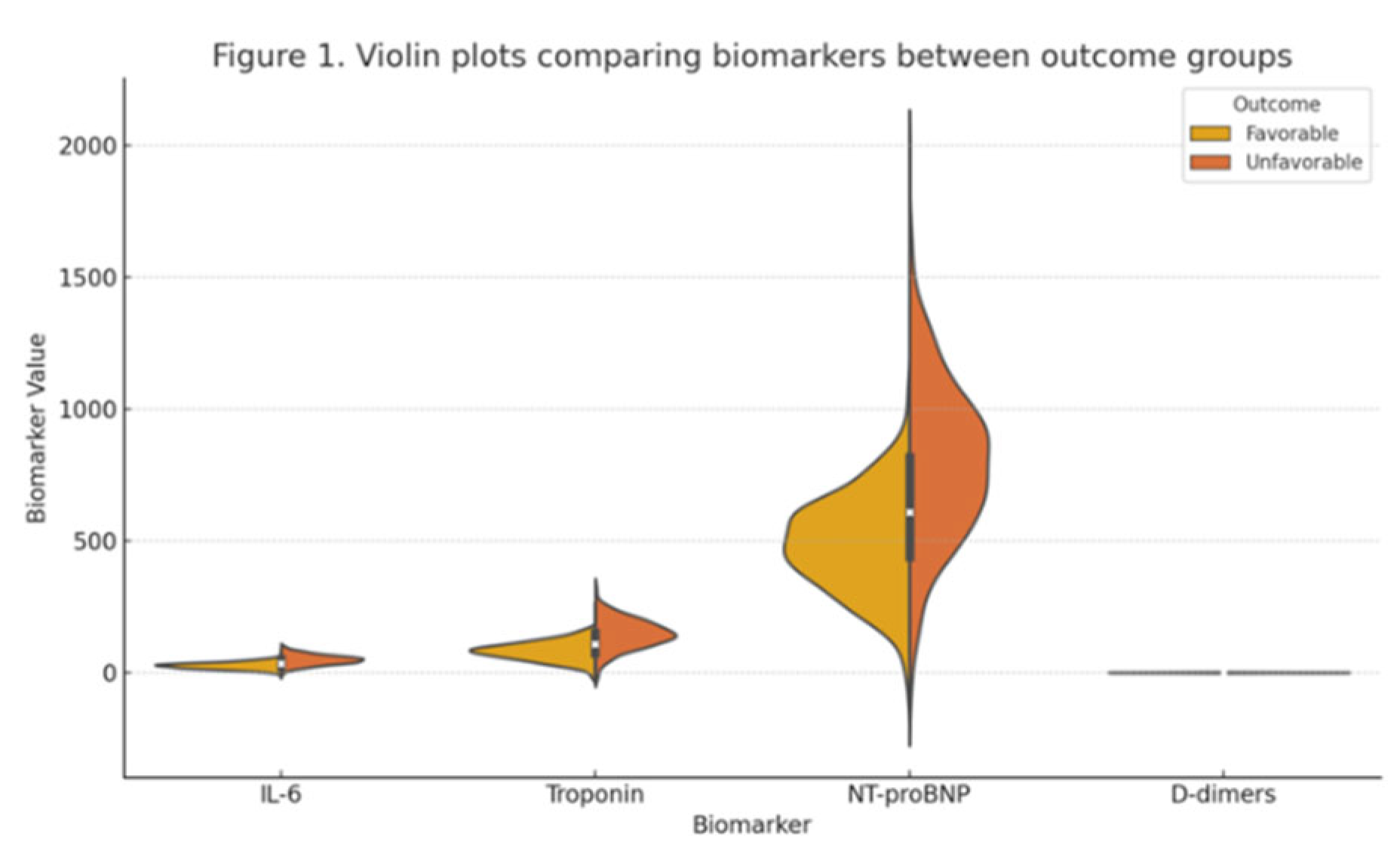

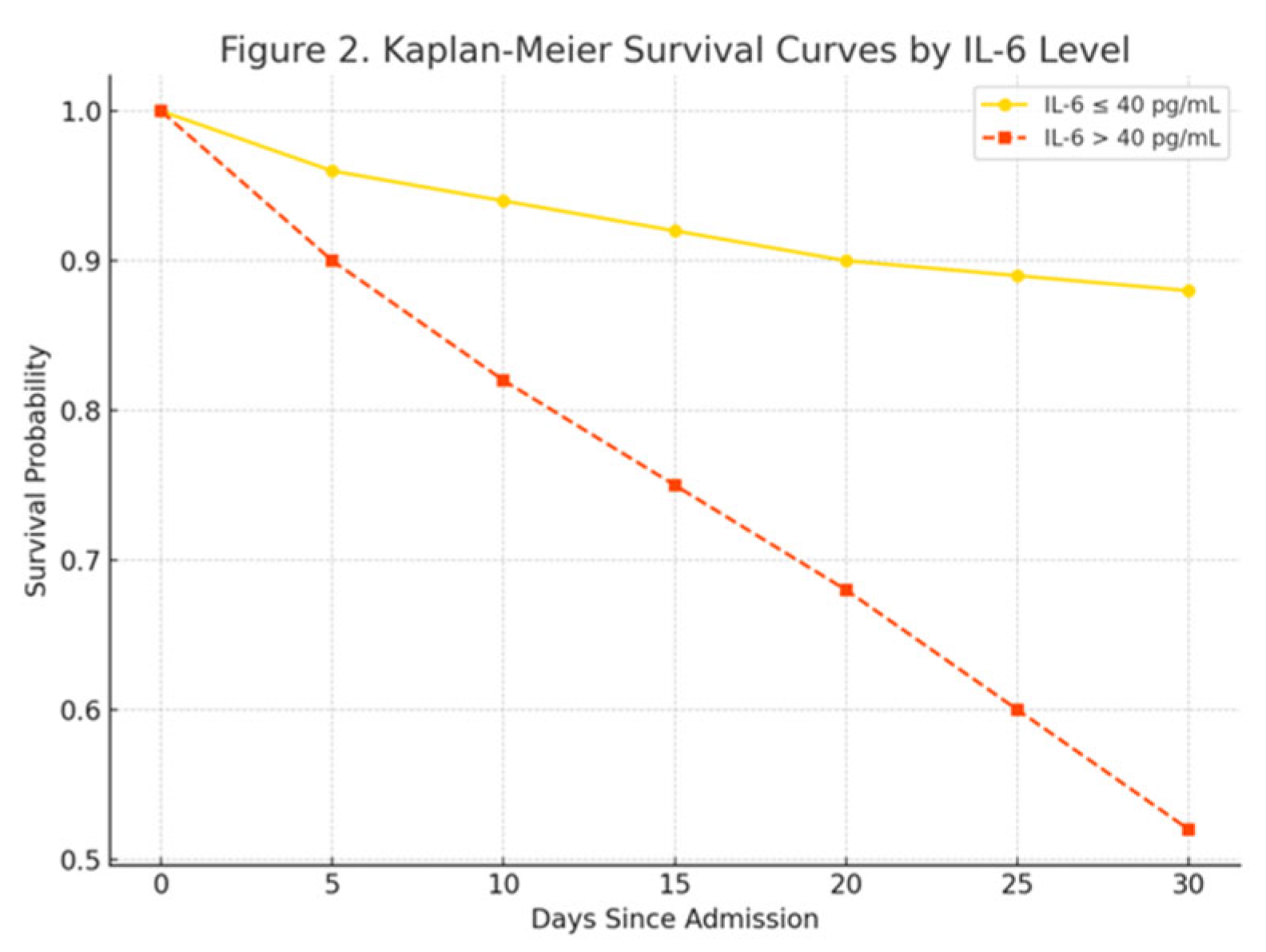

3.2. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Unfavorable Outcomes

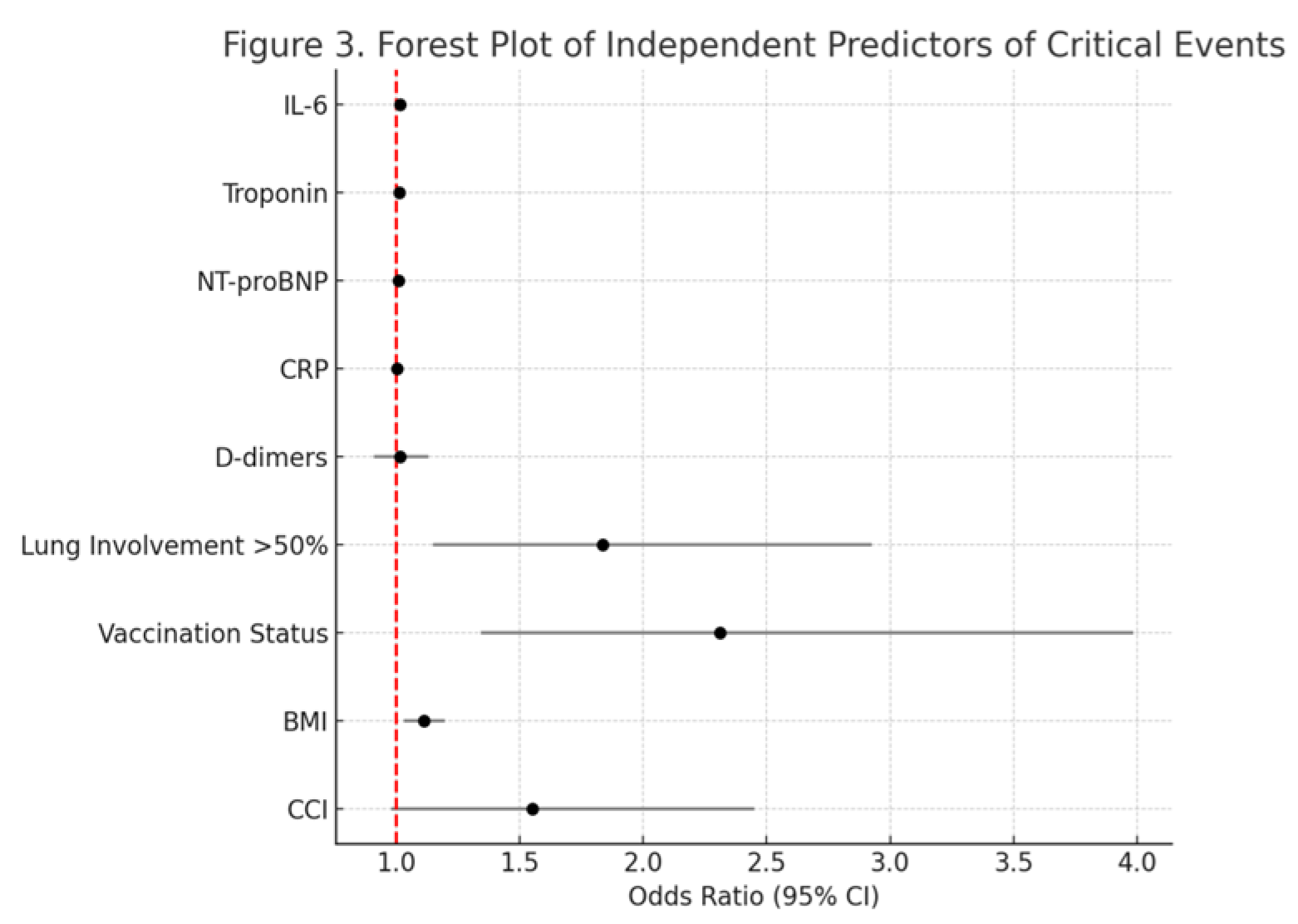

3.3. Multivariable Analysis of Predictors of Unfavorable Outcomes

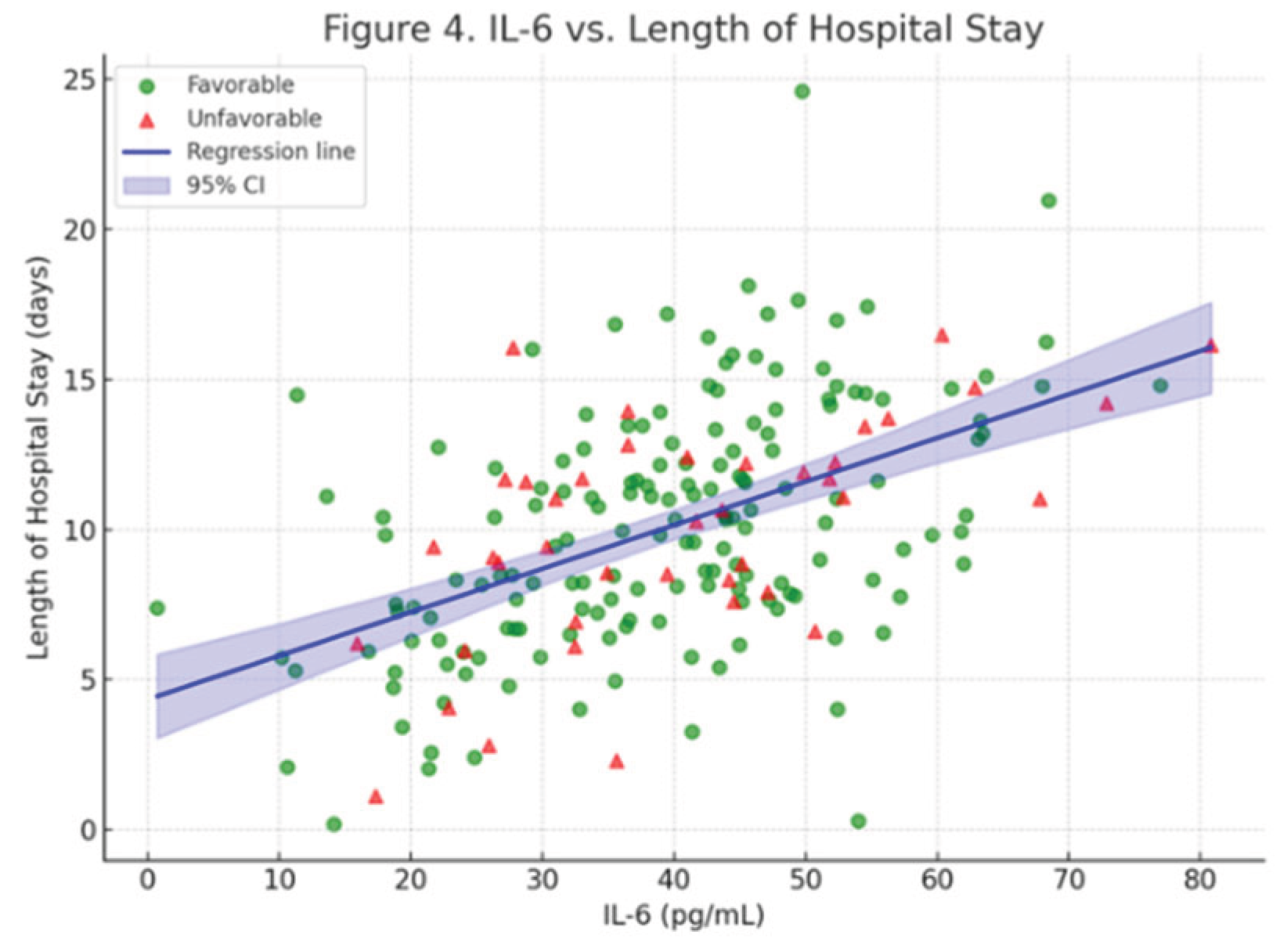

3.4. Linear Regression Analysis of Continuous Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| SpO2 | Oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry |

| CT | Computered Tomography |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve (ROC) |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| COVID 19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| MV | Mechanical Ventilation |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| p | p-value |

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016, 315, 801–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Via, L.; Sangiorgio, G.; Stefani, S.; Marino, A.; Nunnari, G.; Cocuzza, S.; et al. The global burden of sepsis and septic shock. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2024, 5, 456–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.C. COVID-19 sepsis: pathogenesis and endothelial molecular mechanisms based on "two-path unifying theory" of hemostasis and endotheliopathy-associated vascular microthrombotic disease, and proposed therapeutic approach with antimicrothrombotic therapy. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2021, 17, 273–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1054–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chousterman, B.G.; Swirski, F.K.; Weber, G.F. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. SeminImmunopathol. 2017, 39, 517–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhong, Y.; Ali, M.M.; McGuire, F.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo. 2013, 27, 669–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1033–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabay, C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 2006, 8Suppl 2, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, M.; Aab, A.; Altunbulakli, C.; Azkur, K.; Costa, R.A.; Crameri, R.; et al. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor β, and TNF-α: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2016, 138, 984–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kishimoto, T. Immunotherapeutic implication of IL-6 blockade. Immunotherapy. 2012, 4, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, T.; Jurinovic, V.; Arnreich, C.; Lipworth, B.J.; Hellmuth, J.C.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; et al. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2020, 146, 128–36.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H. Interleukin-6 in Covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2020, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, N.I.; Bagiu, I.C.; Vulcanescu, D.D.; Lazureanu, V.; Turaiche, M.; Rosca, O.; et al. IL-6 baseline values and dynamic changes in predicting sepsis mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomolecules. 2025, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinellu, A.; Sotgia, S.; Carru, C.; Mangoni, A.A. B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations, COVID-19 severity, and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 690790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Luo, J. Predictive value of C-reactive protein for disease severity and survival in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ClinExp Med. 2023, 23, 2001–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.; Pranata, R.; Lim, M.A.; Oehadian, A.; Alisjahbana, B. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, and ferritin in severe coronavirus disease-2019: a meta-analysis. TherAdvRespir Dis 2020, 14, 1753466620937175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, H.M.; Ferenczy, A.; Christie BD3rd Ashley, D.W.; Montgomery, A. Correlation of D-dimer and outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Am Surg. 2022, 88, 2115–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Su, Z.; Komissarov, A.A.; Liu, S.L.; Yi, G.; Idell, S.; et al. Associations of D-dimer on admission and clinical features of COVID-19 patients: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 691249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 802–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 811–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.W.; Aronow, W.S. COVID-19, cardiovascular diseases and cardiac troponins. Future Cardiol. 2022, 18, 135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrsalovic, M.; VrsalovicPresecki, A. Cardiac troponins predict mortality in patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of adjusted risk estimates. J Infect. 2020, 81, e99–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochhegger, B.; Zanon, M.; Altmayer, S.; Mandelli, N.S.; Stüker, G.; Mohammed, T.L.; et al. COVID-19 mimics on chest CT: a pictorial review and radiologic guide. Br J Radiol. 2021, 94, 20200703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shudifat, A.E.; Al-Radaideh, A.; Hammad, S.; Hijjawi, N.; Abu-Baker, S.; Azab, M.; Tayyem, R. Association of lung CT findings in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with patients' age, body weight, vital signs, and medical regimen. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 912752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E.; Muglia, R.; Bolengo, I.; Santonocito, O.G.; Lisi, C.; Angelotti, G.; et al. Quantitative chest CT analysis in COVID-19 to predict the need for oxygenation support and intubation. EurRadiol. 2020, 30, 6770–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Ratnakumar, R.; Collin, S.M.; Berrocal-Almanza, L.C.; Ricci, P.; Al-Zubaidy, M.; et al. Chest CT features and functional correlates of COVID-19 at 3 months and 12 months follow-up. Clin Med (Lond). 2023, 23, 467–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragomir, R.; Popa, D.; et al. IL-6 as a predictor of hospitalization and morbidity in COVID-19: a 2024 meta-analysis. Viruses 2024, 16, 1789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, T.; Jurinovic, V.; Arnreich, C.; Lipworth, B.J.; Hellmuth, J.C.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; et al. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2020, 146, 128–36.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1033–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mesa, J.E.; Galindo, M.; Garcia-Montoya, L.; Rojas-Villarraga, A.; Mendoza-Pinto, C.; Barahona-Correa, J.; et al. Elevated troponin in critically ill COVID-19 patients: association with ICU outcomes and mortality. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 802–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Zhao, D.; Momeni, A.; Rojas, S.V.; Chang, A.Y. Prognostic value of troponin in COVID-19-associated myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2024, 110, 342–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojón-Álvarez, R.; López-Cheda, A.; Rey, J.R.; Buño-Soto, A.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; García-Lledó, A.; et al. Prognostic significance of NT-proBNP in patients with COVID-19 without heart failure: insights from a retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1427652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 811–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhuri, B.; Aikawa, T.; Lau, E.S.; Li, S.X.; et al. Elevated natriuretic peptides in patients with severe or critical COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2022, 49, e207404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslé MM, Brown KE, Mook P, Campbell H, WHO Working Group. Estimated number of lives saved and hospitalizations averted by COVID-19 vaccination in the WHO European Region between December 2020 and March 2023: a modelling study. Lancet Respir Med. 2024, 12, 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, I.A.; Aramă, V.; Nicolau, D.; Popescu, C.P.; Iliescu, M.; Radu, A.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage in ICU patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter retrospective study in Romania. Crit Care. 2023, 27, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1054–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stan, D.; Ionescu, A.; Popescu, L.; et al. Impact of body mass index on outcomes in Romanian ICU COVID-19 patients: a multicenter cohort study. BMJ Open. 2024, 14, e056789. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L.; Yoo, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; et al. Obesity and COVID-19 mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021, 45, 987–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Domingo, M.; Bermejo-Martín, J.F.; Juanes-Bénitez, R.G.; et al. Body mass index and immune response in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a Spanish cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021, 45, 1123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, H.M.; Ferenczy, A.; Christie BD3rd Ashley, D.W.; Montgomery, A. Correlation of D-dimer and outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Am Surg. 2022, 88, 2115–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Su, Z.; Komissarov, A.A.; Liu, S.L.; Yi, G.; Idell, S.; et al. Associations of D-dimer on admission and clinical features of COVID-19 patients: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 691249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleyjeh, I.M.; Kashour, Z.; Damlaj, M.; Riaz, M.; Tlayjeh, H.; Altannir, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. ClinMicrobiol Infect. 2021, 27, 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derde, L.P.G.; Gordon, A.C.; McArthur, C.J.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Al-Beidh, F.; Benfield, T.; et al. Effectiveness of tocilizumab, sarilumab, and anakinra in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Thorax. 2025, 80, 267–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, X. Effect of subcutaneous vs intravenous tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a systematic review. Eur J ClinPharmacol. 2024, 80, 1523–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Value (n=207) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 68.7 (11.2) |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 112 (54.1%) |

| Vaccination Status | |

| Unvaccinated, n (%) | 176 (85.0%) |

| Vaccinated, n (%) | 31 (15.0%) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Days to Admission, Mean (SD) | 4.2 (1.5) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 64 (30.9%) |

| Frequent Alcohol Consumption, n (%) | 78 (37.7%) |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 28.7 (3.7) |

| Comorbidities | |

| CCI Score, Mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.3) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 169 (81.6%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 72 (34.8%) |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 42 (20.3%) |

| CT Severity Score | |

| <25% Lung Involvement, n (%) | 52 (25.1%) |

| 25–50% Lung Involvement, n (%) | 74 (35.7%) |

| >50% Lung Involvement, n (%) | 81 (39.1%) |

| Oxygenation and Severity | |

| Oxygen Saturation at Baseline, Mean (SD) | 90.1 (5.7) |

| Oxygen Flow >15 L/min, n (%) | 95 (45.9%) |

| SOFA Score, Mean (SD) | 6.3 (2.4) |

| Baseline Biomarkers, Mean (SD) | |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 32.4 (15.6) |

| Troponin (ng/L) | 98.7 (45.2) |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 567.2 (234.1) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 111.8 (45.2) |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| D-dimers (µg/mL) | 1.1 (0.8) |

| EKG Changes | |

| EKG Changes, n (%) | 55 (26.6%) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| Remdesivir | 189 (91.3%) |

| Antibiotics | 177 (85.5%) |

| Corticosteroids | 204 (98.6%) |

| Tocilizumab | 12 (5.8%) |

| Length of Stay | |

| Length of Stay (days), Mean (SD) | 14.3 (8.0) |

| Outcomes, n (%) | |

| ICU Admission | 42 (20.3%) |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 38 (18.4%) |

| Death | 28 (13.5%) |

| Characteristic | Favorable (n=155) | Unfavorable (n=52) | p-Value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 66.3 (10.4) | 76.2 (9.8) | 0.0001 |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 83 (53.5%) | 29 (55.8%) | 0.763 |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 27.3 (3.4) | 30.5 (3.3) | 0.0003 |

| Vaccination Status, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Vaccinated | 31 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Unvaccinated | 124 (80.0%) | 52 (100.0%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| CCI, Mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.3) | 0.0002 |

| CT Severity, n (%) | |||

| <25% | 44 (28.4%) | 8 (15.4%) | |

| 25–50% | 58 (37.4%) | 16 (30.8%) | |

| >50% | 53 (34.2%) | 28 (53.8%) | |

| Oxygenation and Severity | |||

| Oxygen Saturation, Mean (SD) | 90.2 (5.9) | 87.3 (8.1) | 0.194 |

| Oxygen Flow >15 L/min, n (%) | 98 (63.2%) | 43 (82.7%) | 0.072 |

| SOFA Score, Mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.1) | 7.8 (2.5) | 0.025 |

| Baseline Biomarkers, Mean (SD) | |||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 27.3 (12.8) | 48.7 (19.4) | 0.012 |

| Troponin (ng/L) | 78.9 (34.6) | 145.2 (56.3) | 0.008 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 489.3 (189.7) | 789.4 (298.2) | 0.015 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 111.8 (45.2) | 111.8 (45.2) | 0.950 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.4) | 0.089 |

| D-dimers (µg/mL) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.920 |

| EKG Changes | |||

| EKG Changes, n (%) | 41 (26.5%) | 14 (26.9%) | 0.950 |

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCI | 1.550 | 0.980–2.452 | 0.060 |

| IL-6 | 1.016 | 1.004–1.028 | 0.013 |

| Troponin | 1.013 | 1.003–1.023 | 0.017 |

| NT-proBNP | 1.009 | 1.000–1.018 | 0.049 |

| CRP | 1.002 | 0.992–1.012 | 0.910 |

| D-dimers | 1.015 | 0.910–1.132 | 0.930 |

| Lung Involvement (>50%) | 1.835 | 1.150–2.927 | 0.011 |

| Vaccination Status (Unvaccinated vs. Vaccinated) | 2.312 | 1.342–3.986 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 1.112 | 1.032–1.198 | 0.005 |

| Variable | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (per pg/mL) | 0.120 | 0.078–0.162 | <0.001 |

| Troponin (per ng/L) | 0.080 | 0.065–0.095 | <0.001 |

| D-dimers (per µg/mL) | 0.150 | -0.650–0.950 | 0.850 |

| Lung Involvement (>50% vs. ≤50%) | 2.650 | 1.290–4.010 | <0.001 |

| Age (per year) | 0.045 | -0.015–0.105 | 0.140 |

| CCI | 0.430 | 0.110–0.750 | 0.010 |

| Vaccination Status (Unvaccinated vs. Vaccinated) | -2.500 | -4.082–-0.918 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 0.300 | 0.100–0.500 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).