1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, led to severe respiratory illness and high mortality rates globally [

1,

2]. While most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 experienced mild to moderate symptoms, a subset of patients developed a severe disease, characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ dysfunction, and in some cases, death. This severe clinical presentation is often attributed not only to viral replication but also to an excessive and dysregulated immune response, commonly referred to as a “hyperinflammatory response” or “cytokine storm” [

3]. The hyperinflammatory response in COVID-19 is driven by an over-activation of immune cells, particularly macrophages and T cells, leading to the release of high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. These cytokines contribute to extensive tissue damage, particularly in the lungs, causing the endothelial injury, increased vascular permeability, and alveolar flooding seen in severe COVID-19 cases [

4].

Hyperinflammatory syndrome in COVID-19 (cHIS) is largely mediated by over-activated macrophages and T cells, leading to a cascade of immune reactions that amplify the inflammatory response. This phenomenon has significant implications for patient management, as the hyperinflammatory state not only worsens lung injury but also increases the likelihood of coagulopathy and systemic complications [

5]. Several scoring systems have been developed or adapted to help assess and quantify inflammation in COVID-19 patients. These scores can assist clinicians in predicting disease severity, guiding treatment, and identifying patients who may benefit from immunomodulatory therapies [

6]. Clinical criteria and laboratory parameters incorporated in the cHIS score can be helpful tools in identifying patients with COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome, aiming to recognize and manage those at risk of severe complications, who could potentially benefit from targeted anti-inflammatory therapies [

7].

The aim of this study was to validate the predictive accuracy of the cHIS score for mechanical ventilation requirements and ICU mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a single-center, single-arm, observational cohort study conducted in the Intensive Care Unit of the University Clinical Center of Tuzla, a tertiary referral center in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The study was conducted and the results presented according to the STROBE statement [

8]. Data were collected from electronic medical records and patient charts. All patient data were anonymized to ensure privacy protection.

2.2. Participants

A total of 85 laboratory-confirmed critically ill and hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were ≥18 years of age were enrolled in this study. The patients’, body temperature, laboratory markers of hyperinflammation, length of stay, comorbidities, demographic data and clinical outcomes (mechanical ventilation requirement after ICU admission, and mortality) were recorded.

The inclusion criteria were a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 and admission to the ICU. Patients who received immunomodulatory therapies before admission or who had incomplete medical records were excluded.

2.3. Data Measurement

Hyperinflammatory response was evaluated through the cHIS score, which was calculated on admission to ICU. The following parameters were recorded: 1. Fever (>38⁰C), 2. Macrophage activation with ferritin ≥700 μg/L, 3. Hematological dysfunction with neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) ≥10 or hemoglobin ≤9.2 g/dL and platelet count ≤110,000 cells/L, 4. Coagulopathy with D-dimer ≥1.5 μg/mL, 5. Hepatic injury with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) ≥400 U/L or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥100 U/L and 6. Cytokinemia with interleukin-6 (IL-6) ≥15 pg/mL or triglyceride ≥150 mg/dL or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥15 mg/dL. Each of the six parameters was credited with one point and the sum of all parameters represents the cHIS score. Cut-off points were specified (CHIS score 3) and all the values greater than the cut-off point was taken to predict mortality.

Patients were divided into two groups: those with cHIS scores less than 3, and those with cHIS scores of 3 or higher. The groups were compared according to their clinical outcomes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report clinical and demographic characteristics, laboratory values, and clinical outcomes. Variations in clinical outcomes were examined using box-and-whisker-plots. The central line in the box represented the median value, while the edges of the box depicted the 25th-75th percentiles. The whiskers showed the minimum and maximum values.

The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. When analyzing continuous data, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed, and for categorical data, the chi-square goodness-of-fit test.

The association between the maximum daily cHIS score and in-hospital all-cause mortality was assessed by evaluating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). A similar analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the cHIS score and the requirement for mechanical ventilation. To account for potential influencing factors, sensitivity analyses were performed using appropriate multivariable logistic regression models. For both the mechanical ventilation model and the mortality model, we included the following covariates: cHIS, age, and the number of comorbidities. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R programming language, and statistical significance was indicated by p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

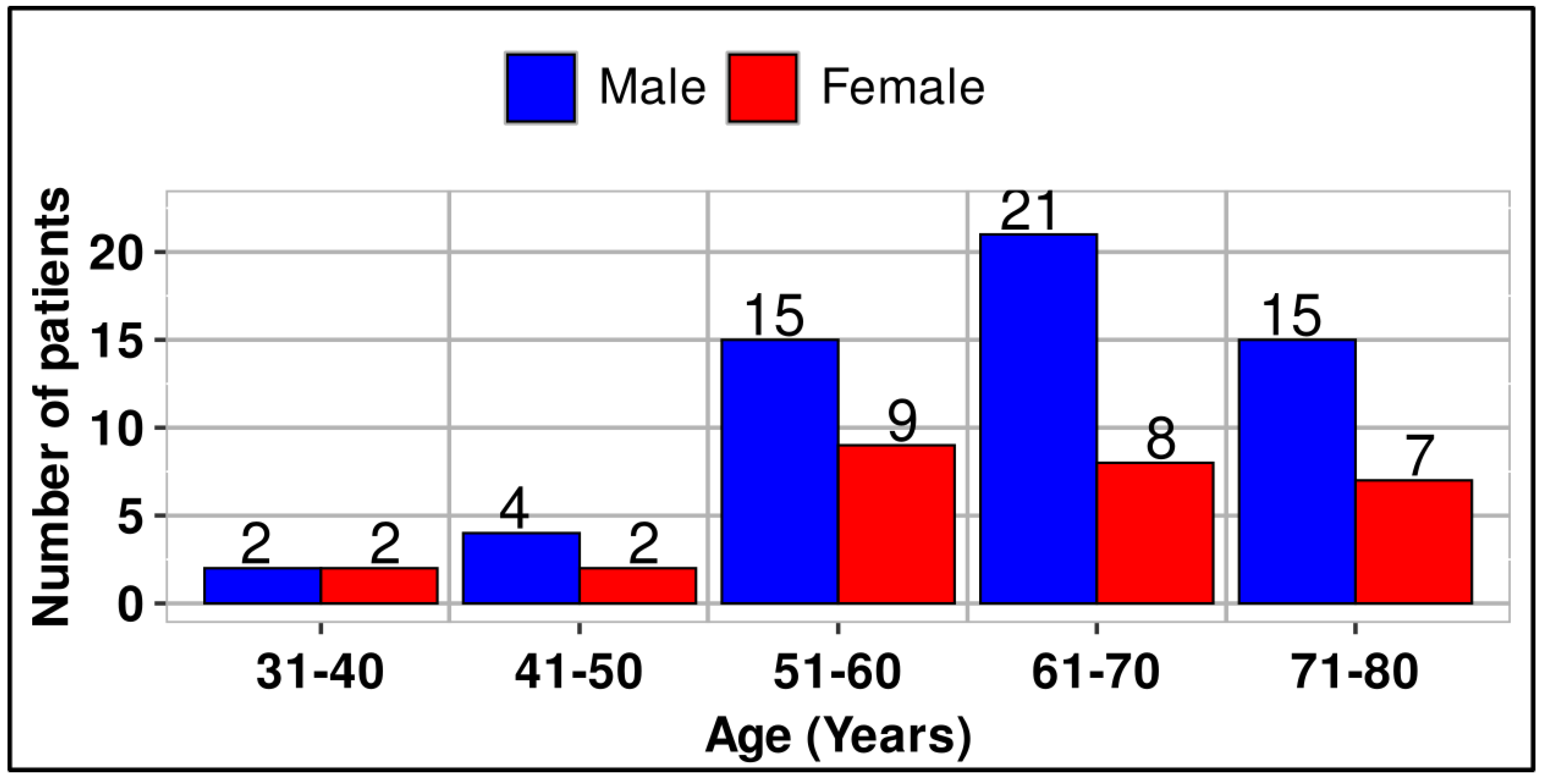

A total of 85 patients were enrolled in this retrospective study, comprising 28 females and 57 males. Patients’ ages ranged from 31 to 78 years, and they were categorized into five age groups (

Figure 1). The difference in numbers between male and female patients was statistically significant (p<0.001).

The COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome scores for 85 patients were calculated. The clinical, laboratory and demographic characteristics of patients with COVID-19, were stratified by peak cHIS score (

Table 1). The median daily cHIS score was 3 (IQR 2–4). All data connected with two subsets of patients, those with cHIS<3 and the second classified group with cHIS≥ 3, are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

It is important to underline that the primary laboratory parameters used in the cHIS score exhibit significant differences between the two patient groups (those with a cHIS score of less than 3 and those with a score of 3 or higher). For instance, ferritin levels (measured in μg/L) are nearly three times greater in patients with a cHIS score of 3 or above (

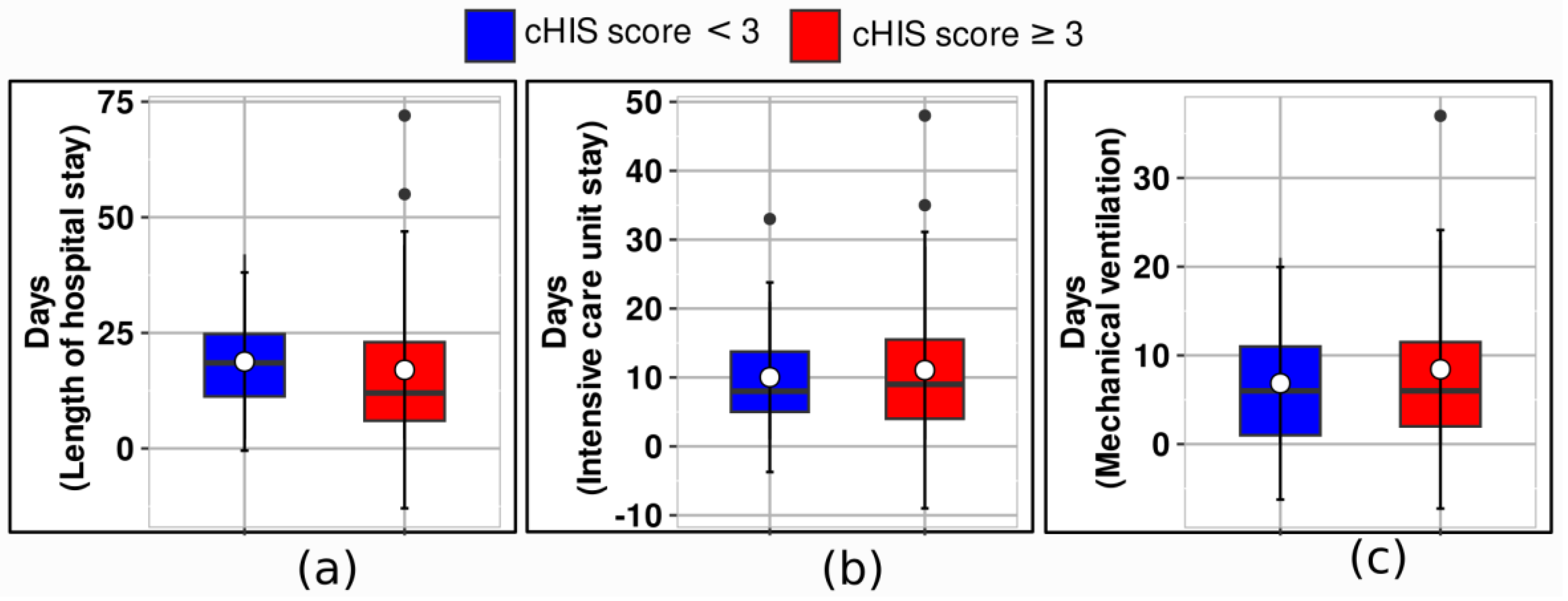

Table 1). There were minimal differences in the length of stay in the ICU and the duration of mechanical ventilation between the two patient groups (

Table 2).

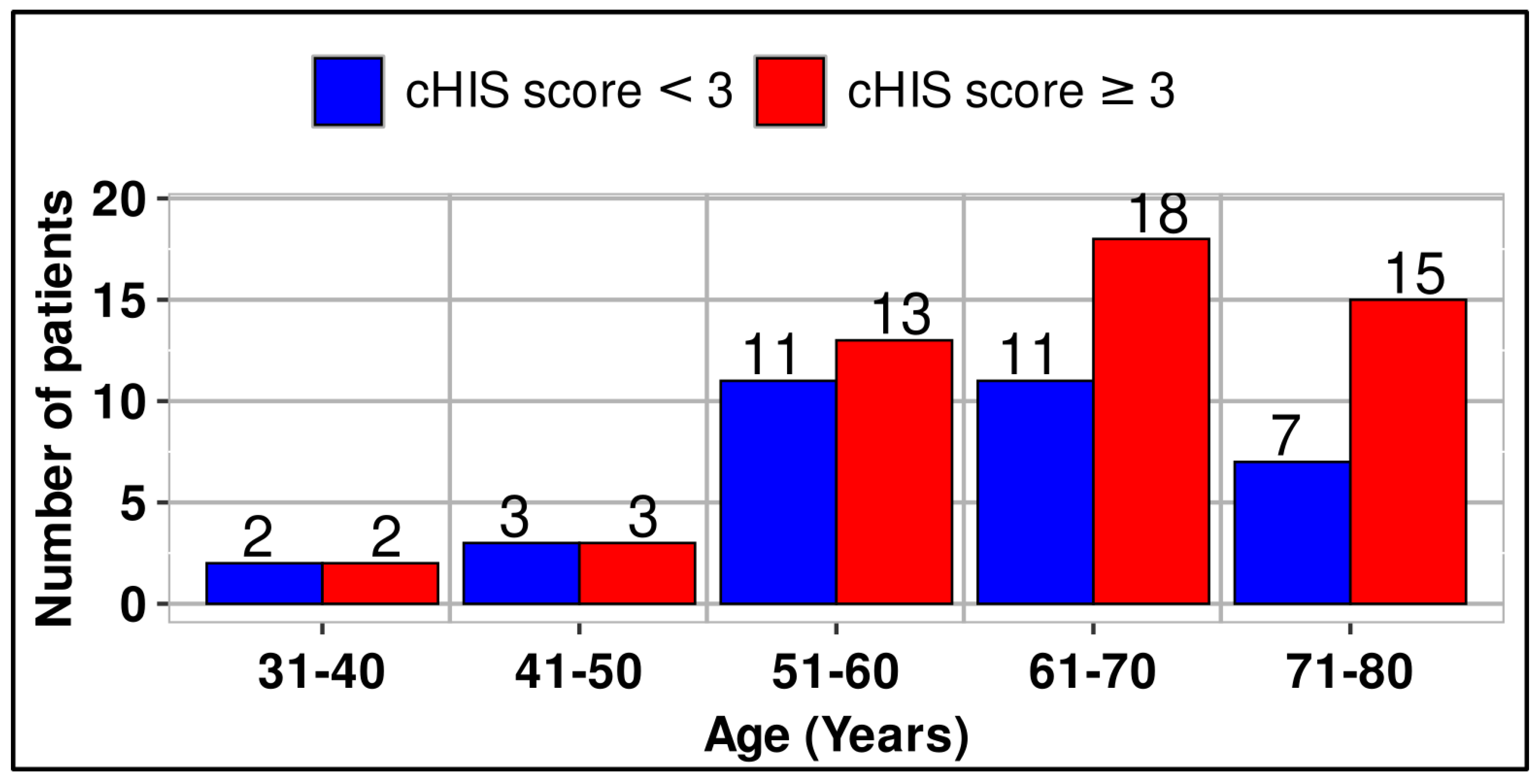

Although the number of patients within the two classified groups is almost the same up to age 60, a greater difference is observed above age 61 in favor of patients with cHIS>3. (

Figure 2)

In

Figure 3, median values and IQR are shown for the length of hospital stay, the ICU stay, and mechanical ventilation. Patients with a score of less than 3 had significantly different outcomes compared to those with a score of 3 or higher across several clinical endpoints. The median length of hospital stay for patients with a score of less than 3 was 19 days (IQR 11–25), while it was 12 days (IQR 6–23) for those with a score of 3 or more.

3.2. Main Results

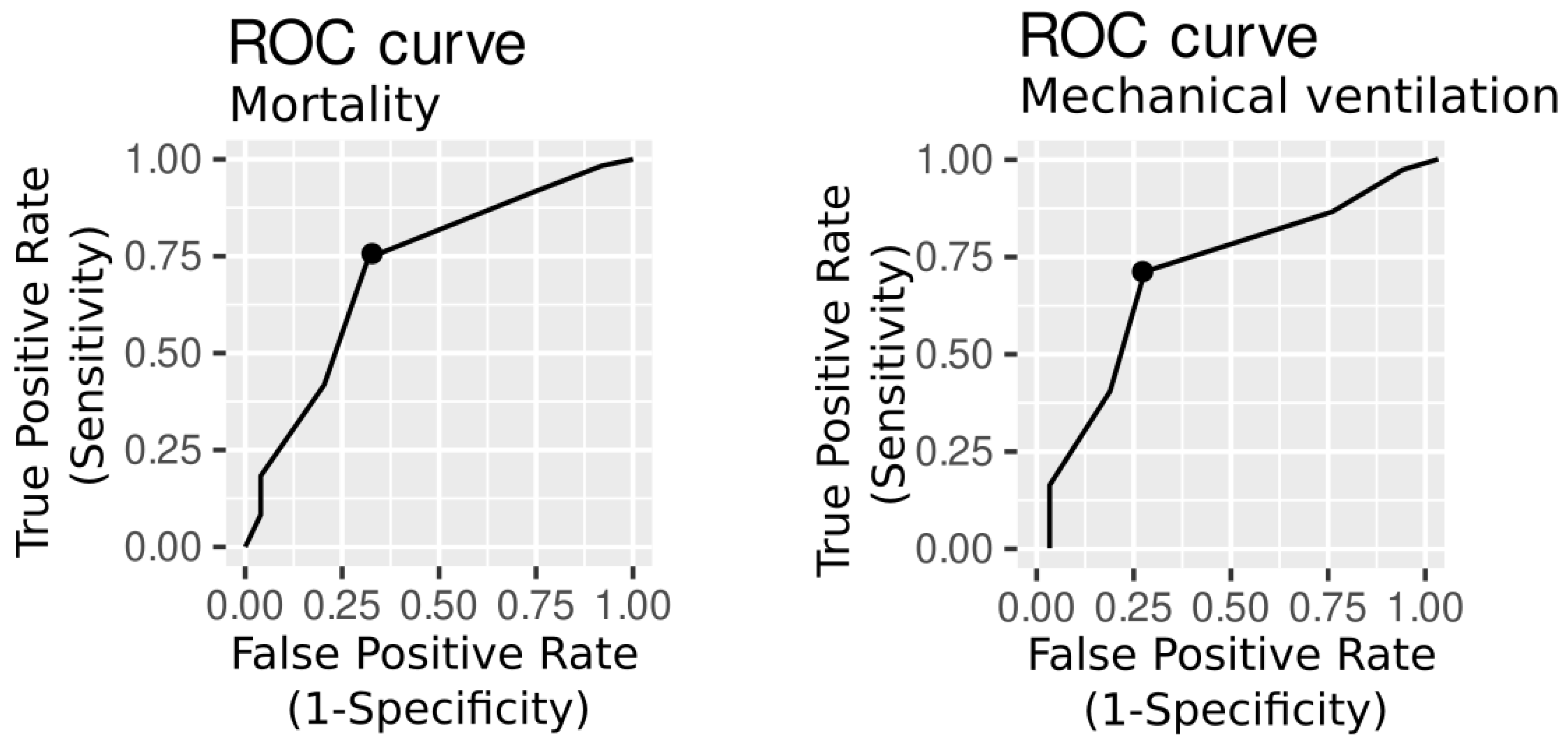

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to assess the cHIS discrimination ability, while Youden Index Analysis was used to determine the optimal cut-off values, including the sensitivity and specificity of the cHIS score. On the basis of the Youden index, an admission cHIS score ≥ 3 had the best accuracy for intensive care unit mortality, and the AUROC was 0.70 (95% CI 0.55–0.83, sensitivity=0.76, specificity=0.66). For mechanical ventilation, the cHIS score was also ≥ 3 and the AUROC was 0.71 (95%CI 0.57-0.81, sensitivity=0.73, specificity=0.65) (

Figure 4).

Bivariate regression for cHIS and mechanical ventilation showed an odds ratio (OR) of 4.9 (95% CI 1.3-23.9, p<0.026) in a sensitivity analysis. The OR in bivariate regression for in-hospital mortality was 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.2), p=0.031.

In the multivariable logistic regression model for mortality, the OR was 1.07 (95% CI 1.0–1.15) adjusted for age and 1.22 (0.78–2.32) adjusted for comorbidities. The cHIS scale remained associated with mortality (OR 4.12 [95% CI 1.02–9.34], p=0.045).

In a multivariable regression model for mechanical ventilation, the OR was 1.09 (95% CI 1.03–1.16) adjusted for age, and 1.26 (0.67–2.0) adjusted for total comorbidities. The cHIS scale was associated with mechanical ventilation (OR 1.42 [95% CI 0.98–2.2], p=0.033)

A post-hoc sensitivity analysis was used to evaluate the frequency and association of individual cHIS criteria with clinical outcomes. At a threshold of three or higher, the scale demonstrated exceptional sensitivity in predicting both mechanical ventilation and mortality. Concerning the laboratory parameters incorporated in the cHIS score, the preceding analysis yielded the following results: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, (sensitivity=0.70, specificity=0.73, AUROC=0.67), C-reactive protein (sensitivity=0.61, specificity=0.82, AUROC=0.72), Lactate dehydrogenase (sensitivity=0.24, specificity= 1.00, AUROC=0.61) and D-dimer (sensitivity=0.69, specificity= 0.73, AUROC=0.71) were most specifically associated with mechanical ventilation. For mortality, C-reactive protein (sensitivity=0.84, specificity=0.59, AUROC=0.74), Lactate dehydrogenase (sensitivity=0.63, specificity=0.94, AUROC=0.80) and D-dimer (sensitivity=0.67, specificity= 0.80, AUROC=0.77) were the most important variables.

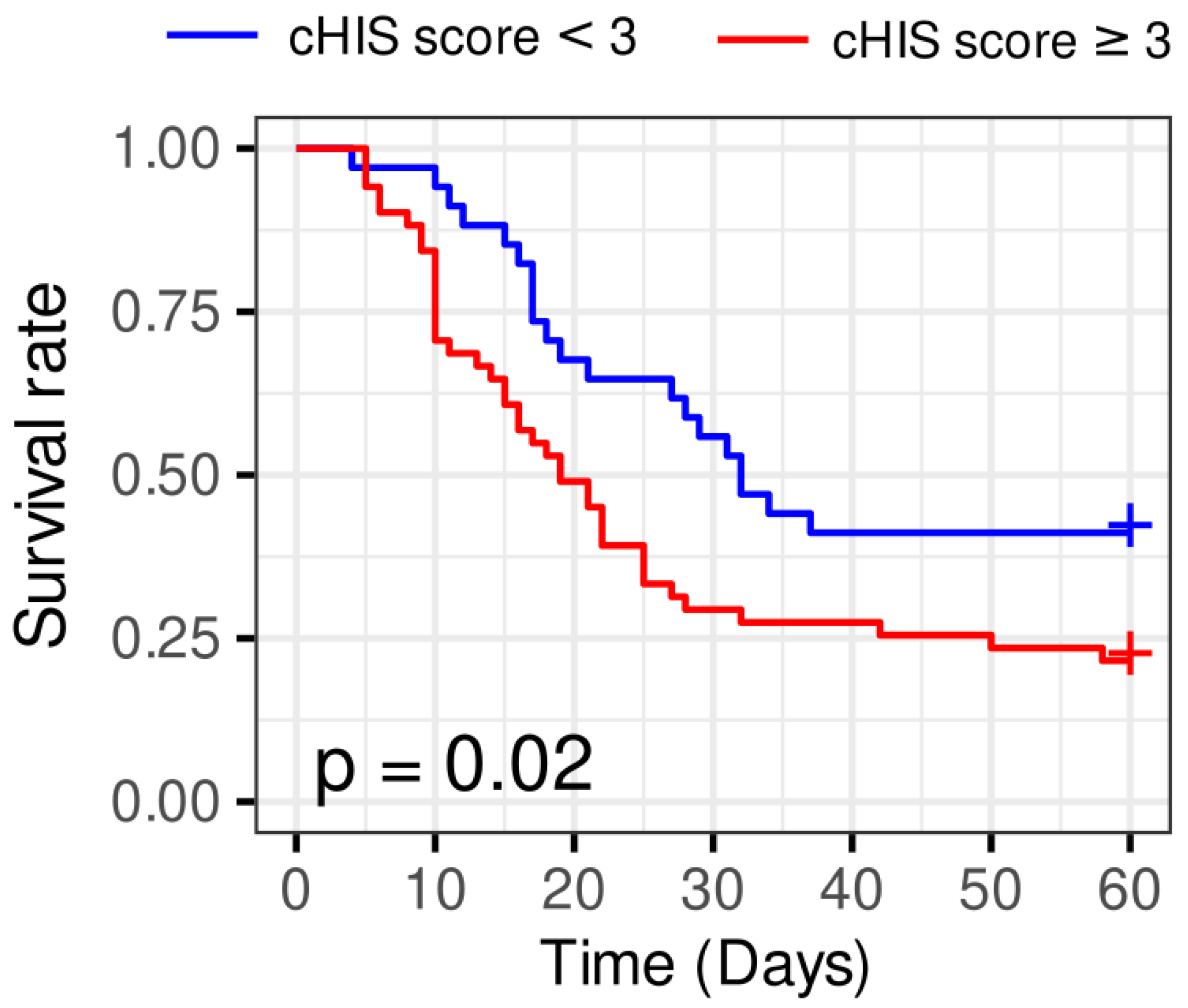

Patients with a cHIS score ≥ 3 had significantly worse survival probabilities than those with a cHIS score < 3, according to the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank test p=0.02). Thus, the cHIS score is related to survival, and worse outcomes are associated with larger scores (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The cHIS score is a reliable prognostic tool for predicting ICU mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. We found that the cHIS score could predict ICU mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation, with area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) values of 0.70 and 0.71, respectively. The optimal cutoff cHIS score of ≥3, determined via the Youden index, offered acceptable sensitivity and specificity. The worse outcomes are associated with larger cHIS scores. Key biomarkers of hyperinflammatory syndrome, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and D-dimer, were strongly associated with mechanical ventilation, while CRP, LDH, and D-dimer were particularly important for predicting mortality. Our results also indicate that the older patients tend to have higher CHIS scores and are more likely to require ICU admission and mechanical ventilation.

However, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings or patient populations. Second, the relatively small sample size (n=85) may reduce the statistical power to detect smaller but clinically significant associations. Third, we excluded patients who received immunomodulatory therapies before admission, which may limit the applicability of our findings to patients already on such treatments. Finally, the lack of long-term follow-up data prevents us from assessing the impact of hyperinflammation on post-ICU recovery and long-term morbidity.

The COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome score was designed to estimate the degree of hyperinflammation in COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital, by calculating the maximum daily cHIS score [

7]. Others evaluated the cHIS score on admission, focusing specifically on patients treated in the ICU [

9]. High cHIS scores, low BMI and the presence of chronic lung disease were important independent predictors of mortality across all cHIS scores [

7], but we also found that CRP, LDH, and D-dimer were predicting mortality.

The specified threshold values of the cHIS score vary across studies. One study [

7] showed that a threshold score of 2 or more was predictive of both mortality and mechanical ventilation. In contrast, it was found that a cHIS score of 3 or more was associated with ICU mortality and invasive mechanical ventilation (6). Further analysis [

10] reported that a cHIS score of 2 or more was associated with higher odds of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and in-hospital mortality. It was demonstrated that a cHIS score of 3 or more was a better predictor of mortality, while a score of 2 or more was more predictive of the need for mechanical ventilation [

11]. We found that the cHIS score can predict ICU mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation, with the optimal cutoff cHIS score of ≥3.

CHIS identifies patients with hyperinflammation, which is strongly associated with poor COVID-19 outcome (12). Various attempts have been made to summarize clinical manifestations and laboratory findings, and facilitate better prediction of clinical outcomes [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Among these efforts the COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome (cHIS) score has emerged as a promising tool for identifying patients at risk of poor outcomes. Early identification of high-risk patients using the cHIS score can facilitate timely interventions, such as immunomodulatory therapies or advanced respiratory support, potentially improving patient outcomes. Moreover, the cHIS score may also be valuable for other patients with hyperinflammatory syndromes, such as sepsis, septic shock, macrophage activation syndrome, systemic autoimmune diseases, or other viral infections.

5. Conclusions

The cHIS score is a reliable prognostic tool for predicting ICU mortality and mechanical ventilation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Its use supports early risk stratification and targeted interventions to improve patient outcomes. Moreover, the cHIS score may also be a valuable parameter for other patients with hyperinflammatory syndrome.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, J.S. and S.D.; Methodology, J.S.; Software, E.S.; Validation, J.S., S.D. and F.I.H; Formal Analysis, J.S.; Investigation, F.J.HX., L.M., S.S., Resources, J.S.; Data Curation, F.I.H., L.M., S.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, J.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.D.; Visualization, E.S.; Supervision, S.D.; Project Administration, J.S.; Funding Acquisition, J.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Clinical Center Tuzla (No 02-09/2-82/20, date: 20 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Rohaimi, A.H.; Al Otaibi, F. Novel SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and COVID19 disease; a systemic review on the global pandemic. Genes Dis. 2020, 7, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalmurti, N; Christopher, A.; Hunter, C.A. Cytokine Storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2020, 53, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tiwari, S.; Deb, M.K.; Marty, J.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020, 56, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Gouveia, M.I.M.; Marcelino, B.D.R.; Santos, C.S.D.; Lima, K.V.B.; et al. Hyperinflammatory Response in COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Viruses. 2023, 6, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merad, M.; Martin, J.C. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nature Reviews Immunology 2020, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, M.; Halacli, B.; Yuce, D.; Gunegul, Y.; Ersoy, E.O.; Topeli, A. Assessment of Admission COVID-19 Associated Hyperinflammation Syndrome Score in Critically-Ill COVID-19 Patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2023, 38, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.J.; Peltan, I.D.; Jensen, P.; Hoda, D.; Hunter, B.; Silver, H.; et al. Clinical criteria for COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: A cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e754–e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzunlulu, M.; Maraşli, H.Ş.; Eken, E.; İncealtin, O.; Vahaboğlu, H. Hyperinflammatory Syndrome in Patients with COVID-19. Bezmialem Science. 2023, 11, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.O.; He, J.X.; et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1708–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descalsota, JRD; Cana, AWR; Chin, II; Orcasitas, JF. Identifying COVID-19 Confirmed Patients at Elevated Risk for Mortality and Need of Mechanical Ventilation Using a Novel Criteria for Hyperinflammatory Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort, Single-center, Validation Study. Acta Med Philipp [Internet]. 2024, Jun.26 [cited 2024Dec.25].

- Hsu, TY; D’Silva, KM; Patel, NJ; Wang, J; Mueller, AA; Fu, X; et al. Laboratory trends, hyperinflammation, and clinical outcomes for patients with a systemic rheumatic disease admitted to hospital for COVID-19: a retrospective, comparative cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021, 3, e638–e647.

- Yang, A.; Liu, J.; Tao, W.; Li, H. The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, C.J.; Wooster, L.; Sigurslid, H.H.; Li, R.H.; Jiang, W.; Tian, W.; et al. Estimating risk of mechanical ventilation and mortality among adult COVID-19 patients admitted to Mass General Brigham: the VICE and DICE scores. EClinical Medicine. 2021, 33, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastin, C.; Eastin, T. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease, 2019 in China. J Emerg Med. 2020, 58, 711–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.J.; Crooks, C.; Naja, M.; Ledlie, A.; Goulden, B.; Liddle, T.; et al. COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation and escalation of patient care: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2020, 2, e594–e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).