1. Introduction

The US swine industry is one of the largest pork contributors to the global pork value chain, contributing approximately 12% of the world’s pork, estimated at more than 8 billion USD in export value [

1,

2]. As such, the swine industry is economically crucial in the US and globally. Due to its vertical integration [

3] the industry is often troubled by various endemic viral and bacterial diseases resulting in huge financial losses e.g., more than USD 600m per year from PRRSV [

4]. Although the swine industry appears to have mastered how to mitigate the impacts of most of these swine diseases through vaccination and application of different biosecurity measures, the ever-present threat of introduction of foreign animal diseases (FADs) such as African Swine Fever (ASF) [

5] necessitates regular evaluation and improvement of these biosecurity measures. Previous studies have highlighted some inconsistencies and complexities in the adoption of biosecurity recommendations such as those described in the secure pork supply (SPS) plan [

6,

7]. As part of a larger study [

8], this study aimed to characterize the beliefs, behaviors and practices on the adoption and implementation of biosecurity measures by US production systems on their farms.

2. Materials and Methods

Although this online survey study was intended for all US swine production enterprises, the responding production enterprises were exclusively from the Midwest region. We recorded feedback from 122 pig producers in the Midwest US and beyond between December 2021 and September 2022 using Qualtrics. We used an anonymized self-administered online questionnaire to collect data for our study (

Supplementary material 1). The questionnaire was disseminated using a link emailed through outreach networks and databases, pork council and associations such as the American Association for Swine Veterinarians. The questionnaire was developed borrowing tools from similar studies [

7,

9,

10]. We subsequently pretested the questionnaire among 10 veterinarians, extension and producers and used their feedback to update and refine the questions before deployment for data collection. The data captured details on experience of the respondents in swine production, perception of FAD risk/threat and behavioral, normative and control beliefs regarding biosecurity practices as prescribed in the secure pork supply (SPS) plan [

6]. All data was handled in accordance with recommended data privacy and protection guidelines. Descriptive statistical analysis using R 4.2.0 software [

11] including frequency summaries statistics were done to identify underlying patterns of biosecurity practices among respondents. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were not used in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or generation of any content in this study.

3. Results and Discussion

The response rate to our survey was 44.3% (54/122) considering the number of individuals who clicked on the survey link (N=122) as the total. The total number of responses was 54 and thus subsequent analysis was based on N=54 as the sample population. The mean age of the respondents was 44.1± 12.9 years, with a median of 44 years and ranging from 15-64 years. These farmers had also been in swine production for 23.0± 14.8 years, with a median of 20 years and ranging from 2-58 years. More than half 53.7% (29/54) of the respondents had college level education, and a quarter of the respondents had high school level education. About two-thirds (68.5%, 37/54) of the respondents to the questionnaire were independent producers and about 22.2% (12/54) were strictly finisher farms. Most 53.7% (29/54) of the responding operations had an inventory of 1-99 pigs and 16.7% (9/54) had an inventory of more than 5000 pigs. The distribution of these demographics suggested that our study population was largely representative of the greater swine production industry in the region. However, more participants from the diverse production and operation types would have enriched the study for better generalizability.

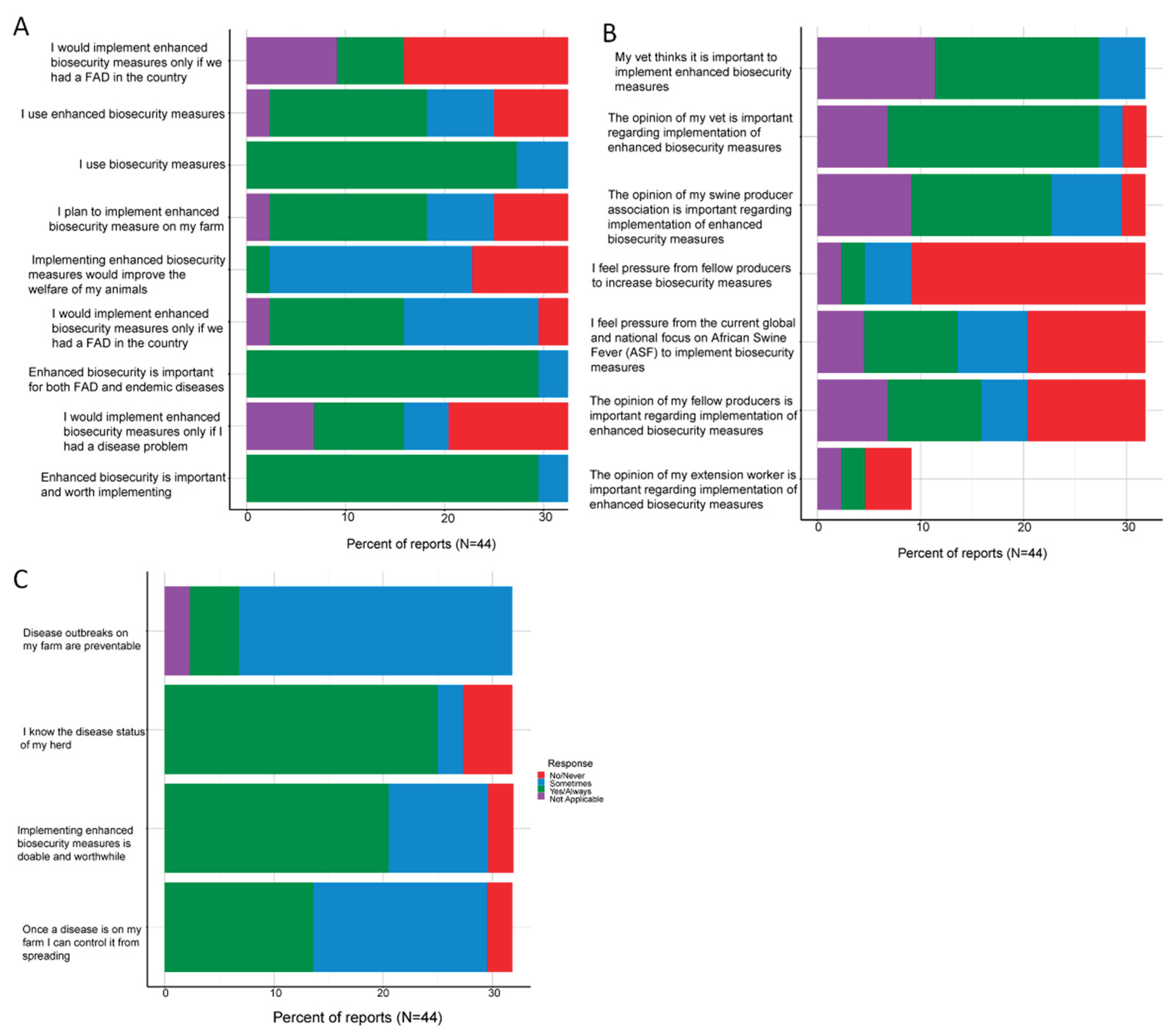

Among the respondents who answered questions on their perceptions and practices of implementing biosecurity measures various factors influenced their actions and response to endemic or foreign animal diseases. Overall, the operations that responded believed that they always (48.1%, 26/54) or at least sometimes (33.3%, 18/54) implemented biosecurity measures. Similarly, most responding operations believed that enhanced biosecurity was always (72.2%, 39/54) important and worth implementing or at least sometimes (11.1%, 6/54). In equal measure, respondents felt that enhanced biosecurity was important for both FAD and endemic diseases. Additionally, 50% (27/54) indicated they would use enhanced biosecurity if there was a threat of FAD in the country (

Figure 1 A). Some of the primary biosecurity practices where we observed some discordance in our study population were the presence and use of a functional line of separation (LOS) to distinguish between clean and dirty areas, and whether movements between clean and dirty areas were monitored in any form. We are not sure why a majority (63% - 34/54) of our study population chose not to indicate whether they had a functional LOS on their premises suggesting that this may be a sensitive issue that most production systems preferred not to disclose or misunderstand what the question aimed to address. However, of those who responded, 90% (18/20) either always or sometimes observed LOS and used it appropriately. Despite these respondents also indicating that movements across the LOS were restricted, more than half (57.9% - 11/19 who responded to the question) never record or tracked movements across the LOS on their premises. Good biosecurity practices recommend tracking LOS crossings to allow for easier identification of any breaches or routes of contamination, especially in cases of outbreaks. More awareness on how to effectively use LOS may be beneficial to the industry for improved disease management.

Actions by the respondents to implement enhanced biosecurity measures or update their operation’s biosecurity are influenced by opinions from different quarters. Attending veterinarians and the swine producer’s association opinions were most influential. The majority of the respondents indicated that their veterinarians always (29.6%, 16/54) thought it was important for them to implement enhanced biosecurity measures in their operations, and most (53.7%, 29/54) always felt that their vet's opinion regarding the implementation of enhanced biosecurity measures was important. The majority of the respondents (59.3%, 32/54) also never felt any pressure from fellow producers to increase biosecurity measures in their operations. Respondents had mixed feelings about how the global threat of African Swine Fever (ASF) influenced their operation's biosecurity, with 20.4% (11/54) saying that they always felt pressure from global and national focus on ASF to implement biosecurity measures, while almost twice as many (37%, 20/54) never felt the need to alter their operations (

Figure 1 B).

Overall, most (68.5%, 37/54) respondents felt that they knew the health status of their herds well all the time. Respondents generally felt that disease outbreaks were not always, but sometimes preventable in their enterprises (59.3%, 32/54). Largely, respondents believed that in the case of a disease outbreak they were able, always (44.4%, 24/54) or sometimes (46.3%, 25/54), to control it from spreading (

Figure 1 C).

Although some respondents believed that they implemented enhanced biosecurity measures on their farms, none of them qualified as practicing all recommended steps of enhanced biosecurity according to the SPS plan. Biosecurity practices considered were the presence of a biosecurity manager, functional perimeter buffer area (PBA), vehicle cleaning /disinfection points external to the farm proper, an active and functional line of separation within the premises where internal biosecurity was strictly managed and movements in and out of clean areas were controlled and monitored. Other practices included the sharing of equipment between farms, ability to restrict access (lock) to farm buildings and the presence of backup plan in the event of an introduction of FAD to the farm[

6]. Both external and internal biosecurity practices are crucial in disease management, i.e., preventing introduction and spread to and from a given farm. For certain diseases such as PEDV, PRRS, influenzas etc., which have multiple routes of transmission including fomite/mechanical spread, the hygiene of vehicles is a crucial biosecurity component [

7,

12,

13,

14,

15]. As such, the presence of disinfection/sanitization stations, external to the farm and PBA minimize the risk of introducing pathogens into the farm. Moreover, internal practices to separate clean areas from dirty areas (LOS) and strict adherence to hygiene practices such as use of protective clothing, showering in and out of these areas has been documented to considerably decrease the risk of disease spread and aid with biocontainment of pathogens [

16,

17].

While there are varied reasons why farms would choose to respond in a certain way to biosecurity threats to their farms, this study has gathered information to provide a snapshot of biosecurity practices on some US swine farms, but that further research, quantitative and qualitative, would be valuable to elucidate how specific factors may influence the variation in biosecurity practices how are implemented on farms. Firstly, a comprehensive sensitization and enabling producers to identify and implement the components of enhanced biosecurity measures would reduce the assumptions that producers were safe and were actually implementing enhanced biosecurity [

7]. Although most of the respondents were confident about the health status of their herds (

Figure 1c) and

supplementary table 1, and FADs may jolt producers in to implementing more stringent biosecurity measures, without adequate understanding and capacity to apply the recommendations of the SPS, the industry would still be at risk should a disease be introduced into the US. For optimal outreach and engagement to these production systems, attending veterinarians would be ideal since their opinions were highly regarded and thus as part of capacity building and awareness, these practitioners ought to be included in those sessions. Lastly, while the confidence of the respondents in their ability to address any health challenges in the production systems can be lauded, proper and regular biosecurity gap assessments would be beneficial to ensure that the true status is always known and where more effort is needed, mechanisms to strengthen biosecurity can be implemented. Our study is, however, limited by the number of respondents and the proportional representation of the different production and operation types. Future research should endeavor to collect more diverse data including organic and backyard production systems which may play a pivotal role in case of disease outbreak.

4. Limitations

The interpretation of these study results was done with some considerations in mind. As is common with online administered surveys, we could not ascertain that the respondents filling in the questionnaire were the intended people on the farms. In this study we intended to involve farm managers/supervisors and veterinarians with intricate knowledge of the daily running of the farms. It is possible that other people within the farm management, e.g. farm owners, filled out some of the questionnaires contributing to either missing data or varied responses to some questions. Another challenge with online surveys is the generally low response since there is no personalized touch. While this could have been a factor in our study, we enlisted the help of numerous outreach officers and used different events to connect with the respondents which increased awareness and encouraged more participants to participate in the study as observed by the grouped number of interactions with our survey within the study period . Finally, we also had to exclude a number of observations due to missing data 10/54 observations. Some of the respondents declined to answer specific questions touching on biosecurity practices on their farms (partial responses for Q4 and 5) which was the focus of our study. At the risk of reducing the sample size and power of our study, we opted to exclude these observations as any attempts to impute data could have led to the introduction of unnecessary biases.

5. Conclusions

Overall and consistent compliance with the recommendations of the SPS biosecurity plan in the US swine industry is yet to be achieved. However, some production systems perceive their current practices as adequate to prevent the introduction and spread of diseases to and from their farms and confidently believe they can manage any disease threats that come their way using current or enhanced biosecurity measures: the definition is not universal among producers. Creating a culture of biosecurity [

18] that involves regular biosecurity assessments and review of biosecurity practices would be beneficial to the management of both endemic and foreign diseases in the US swine industry. Producers and workers should actively be involved in these assessments and the design of biosecurity plans.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: A summary of survey responses on swine biosecurity among swine producers in the US December 2021 and September 2022.

Author Contributions

MC, MA, AP, CC, DM and MM conceptualized the study, sourced for funding and lead industry engagement with veterinarians and production systems. MC, DM, CY synthesized the survey data and cleaned it for analysis. MC, DM, MM analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in reviewing and approving the manuscript for publication.

Funding

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge funding for this project from USDA APHIS Award Number AP21VSSP0000C023. The funder had no other influence on how the study was conducted and the interpretations of the collected data.

Institutional Review Board Statement

A determination was made by the University of Minnesota's Institutional Review Board (IRB) that this study did not constitute research on human subjects and thus was exempt from requiring approval. All participants provided informed consent as sought in the opening statement of the survey.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to confidentiality agreements, anonymized data shall only be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are incredibly grateful to the swine production systems, veterinarians and industry stakeholders for partnering with us in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

References

- USDA FAS - Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS). Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Pork Checkoff Facts & Statistics. Available online: https://porkcheckoff.org/pork-branding/facts-statistics/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Kinsley, A.C.; Perez, A.M.; Craft, M.E.; Vanderwaal, K.L. Characterization of swine movements in the United States and implications for disease control. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2019, 164, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtkamp, D.J.; Kliebenstein, J.B.; Neumann, E.J.; Zimmerman, J.J.; Rotto, H.F.; Yoder, T.K.; Wang, C.; Yeske, P.E.; Mowrer, C.L.; Haley, C.A. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. Journal of Swine Health and Production 2013, 21, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, J. Containing African Swine Fever in the Dominican Republic | Agrilinks. Available online: https://agrilinks.org/post/containing-african-swine-fever-dominican-republic (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- ISU and UMN Secure Pork Supply Plan-Biosecurity. Available online: https://www.securepork.org/pork-producers/biosecurity/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Pudenz, C.C.; Schulz, L.L.; Tonsor, G.T. Adoption of secure pork supply plan biosecurity by U.S. Swine producers. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2019, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chepkwony, M.C.; Makau, D.N.; Yoder, C.; Corzo, C.; Culhane, M.; Perez, A.; Perez Aguirreburualde, M.S.; Nault, A.J.; Mahero, M. A scoping review of knowledge, attitudes, and practices in swine farm biosecurity in North America. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2025, 12, 1507704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richens, I.F.; Houdmont, J.; Wapenaar, W.; Shortall, O.; Kaler, J.; O’Connor, H.; Brennan, M.L. Application of multiple behaviour change models to identify determinants of farmers’ biosecurity attitudes and behaviours. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2018, 155, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culhane, M.; Cardona, C.; Goldsmith, T.J.; Charles, K.S.; Suskovic, G.; Thompson, B.; Starkey, M. Building an all-hazards agricultural emergency response system to maintain business continuity and promote the sustainable supply of food and agricultural products. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2018, 4, 1550907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2022.

- Lopez-Moreno, G.; Davies, P.; Yang, M.; Culhane, M.R.; Corzo, C.A.; Li, C.; Rendahl, A.; Torremorell, M. Evidence of influenza A infection and risk of transmission between pigs and farmworkers. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWaal, K.; Perez, A.; Torremorrell, M.; Morrison, R.M.; Craft, M. Role of animal movement and indirect contact among farms in transmission of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Epidemics 2018, 24, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, J.; Gauger, P.; Harmon, K.; Zhang, J.; Connor, J.; Yeske, P.; Loula, T.; Levis, I.; Dufresne, L.; Main, R. Role of Transportation in Spread of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infection, United States - Volume 20, Number 5—May 2014 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2014, 20, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvis, J.A.; Corzo, C.A.; Machado, G. Modelling and assessing additional transmission routes for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: Vehicle movements and feed ingredients. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2022, 69, e1549–e1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dee, S.; Deen, J.; Rossow, K.; Weise, C.; Eliason, R.; Otake, S.; Joo, H.S.; Pijoan, C. Mechanical transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus throughout a coordinated sequence of events during warm weather. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 2003, 67, 12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Yang, M.; Goyal, S.M.; Cheeran, M.C.J.; Torremorell, M. Evaluation of biosecurity measures to prevent indirect transmission of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. BMC Veterinary Research 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenendaal, H.; Costard, S.; Zagmutt, F.J.; Perez, A.M. Sleeping with the enemy: Maintaining ASF-free farms in affected areas. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022, 9, 935350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).