Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

Plant harvesting and leaf processing

Phytochemical analysis

Experimental animals

Acute toxicity study

Induction of hyperglycemia in experimental animals

Administration of doses of the plant extract

Data analysis

Ethical considerations

Results

Phytochemical analysis of the plant extract

Oral hypoglycemic test

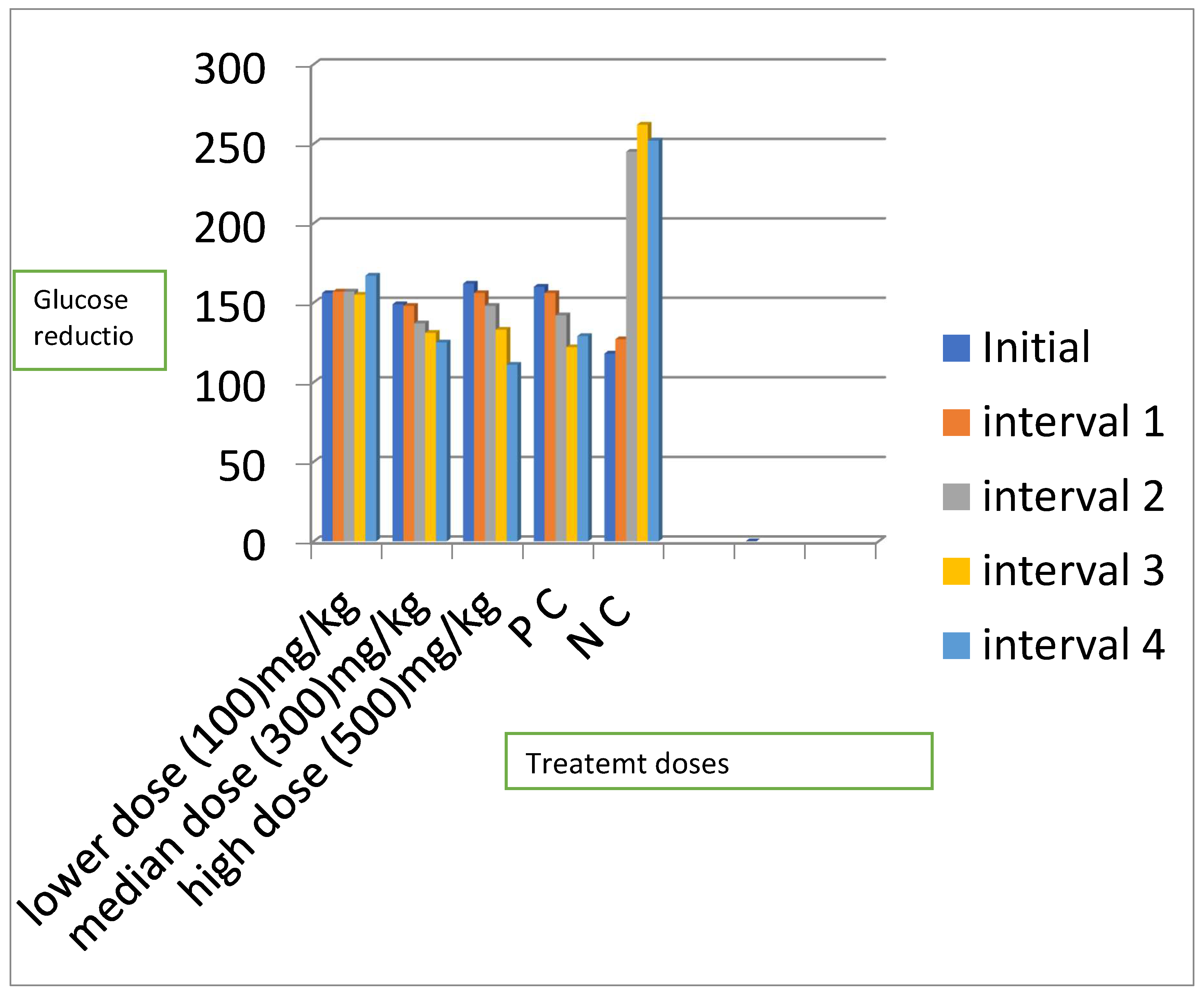

Mean blood glucose levels for all the treatment groups

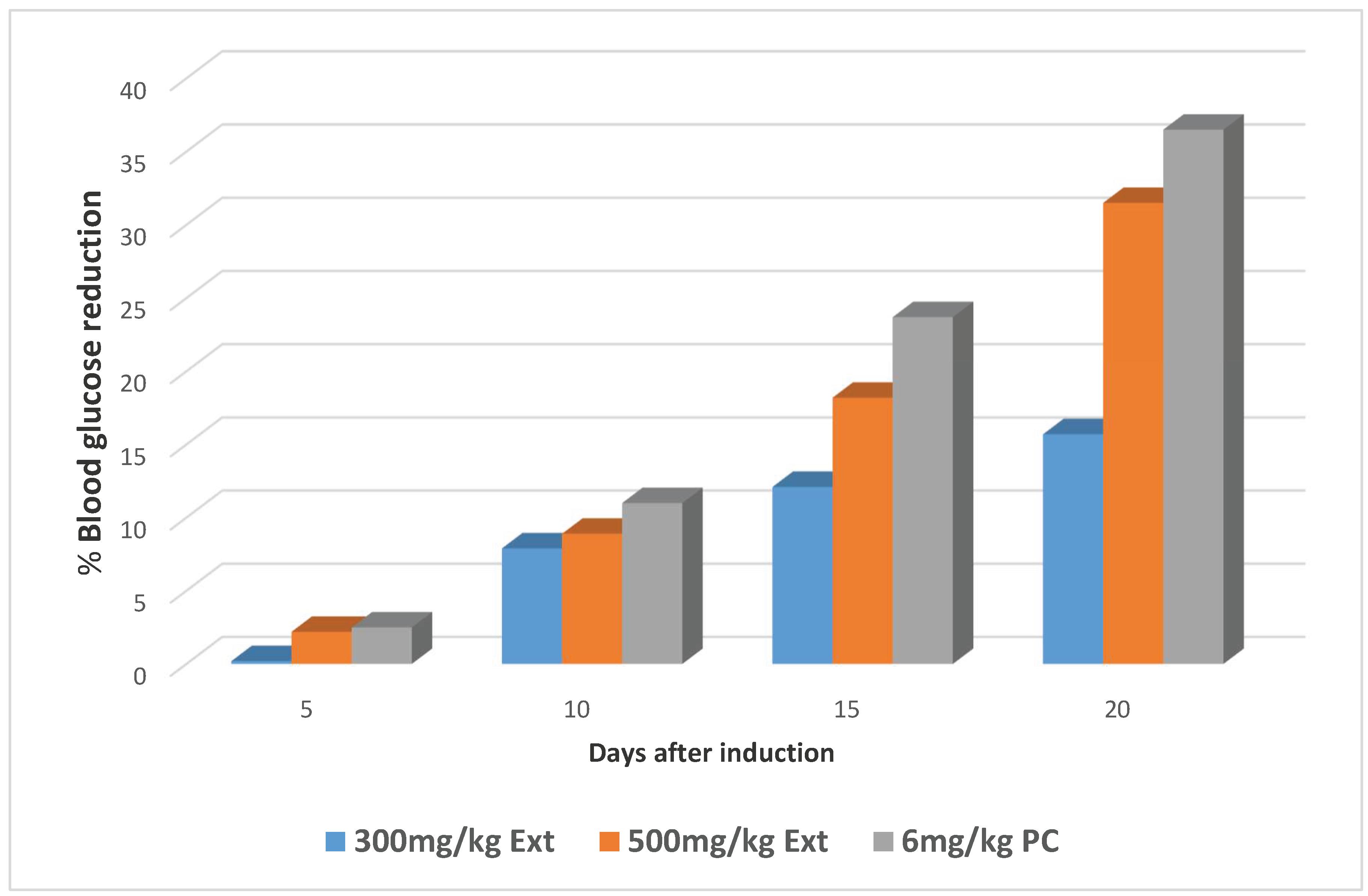

Percentage reduction in the blood glucose levels of the animals for the three significant groups

Acute toxicity of the extract

Discussion

Percentage yield of Extract

Phytochemical analysis

Oral hypoglycemic study

Acute toxicity study

Conclusion

Recommendations

References

- Chang, C. L. T., Lin, Y., Bartolome, A. P., Chen, Y., Chiu, S., & Yang, W. Herbal Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus : Chemistry , Biology , and Potential Application of Selected Plants and Compounds. Evidence-Based Alternative and Complementary medicine. Volume 2013 Article ID 378657 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cicero L. T. Chang,Yenshou Lin, Arlene P. Bartolome,Yi-Ching Chen, Shao-Chih Chiu, and Wen-Chin Yang Herbal Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Chemistry, Biology, and Potential Application of Selected Plants and Compounds. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2013, Article ID 378657, 33 pages 2013. [CrossRef]

- DiTomaso, J.M., G.B. Kyser et al. Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Weed Research and Information Center, University of California. 2013.

- Eweka, A. O. Histological studies of the effects of oral administration of Aspiliaafricana( Asteraceae ) leaf extract on the ovaries of female wistar rats. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 6:57–61. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh M N. Fundamentals of experimental pharmacology.Indian Journal of Pharmacology 3: 36-39 1984.

- International Diabetes Federation. (2015). IDF Diabetes Atlas 2015.

- Jean-Louis Chiasson, NahlaAris-Jilwan, RaphaëlBélanger, Sylvie Bertrand, Hugues Beauregard, Jean-Marie Ékoé, Hélène Fournier, and Jana Havrankova. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Canadian Medical Association Journal 168(7): 859-866 2003.

- LC Taziebou, F-X Etoa, B Nkegoum, CA Pieme, DPD Dzeufiet. Acute and subacute toxicity of Aspilia Africana leaves. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 4(2) 127-134 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ncube, B J, Finnie, J& Van Staden. Quality from the field: The impact of environmental factors as quality determinants in medicinal plants. South African Journal of Botany, 82(12):6-9 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ngugi M P, Murugi N J, Kibiti M C, Ngeranwa J J, Njue M W, Maina D, Gathumbi K P and Njagi N EHypoglycemic Activity of Some Kenyan Plants Traditionally used to Manage Diabetes Mellitus in Eastern Province. Journal of diabetes and metabolism, 2(8):2-4. 2011.

- Nyanzi R, Wamala R and Atuhaire L K, Diabetes and Quality of Life: A Ugandan Perspective. Makerere University. Kampala Uganda. 2013. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2001). Guidance document on the recognition, assessment and use of clinical signs as humane endpoints for experimental animals used in safety evaluation. Series on Testing and Assessment No 19. ENV/JM/MONO.

- Osadebe, P. O., Odoh, E. U., &Uzor, P. F. Natural Products as Potential Sources of Antidiabetic Drugs. British Journal of Pharmacutical Research, 4(17): 2075–2095. 2014.

- Panawala P B, D.C. Abeysinghe, R.M. Dharmadasa. Phytochemical Distribution and Bioactivity of Different Parts and Leaf Positions of PimentaDioica (L.) Merr (Myrtaceae) World Journal of Agricultural Research., 4(5): 143-146 2016. [CrossRef]

- Quy Diem Do, Artik Elisa, AngkawijayaPhuong ,LanTran-Nguyen, Lien HuongHuynh, FelyciaEdiSoetaredjo and SuryadiIsmadji Yi-HsuJu. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatic I; Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 22(3): 296-302 2014. [CrossRef]

- Schorderet, M. Pharmacologie des conce Editions Slatkine Genève, Edition Frison-Roche Paris. Pp33-34. 1992.

- Shrivastava A, Suchita Singh, Sanchita Singh. Phytochemical investigation of different plant parts of Calotropisprocera: International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications,3(8) 1-42018.

- SospeterNgociNjeru, MeshackObonyo. Potency of extracts of selected plant species from Mbeere, Embu County-Kenya against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 10(12):149-157 2016. [CrossRef]

- Spilvallo R, Novero M, Bertea CM, Bossi S, Bonfante P. Truffle volatiles inhibit growth and induce an oxidative burst in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 175:417–424 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ssegawa, P., &Kasenene, J. M. Medicinal plant diversity and uses in the Sango bay area, Southern Uganda. Journal of Ethnopharmacology,113 (3): 521–540. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Switi B. Gaikwad, G. Krishna Mohan and M. Sandhya Rani. Phytochemicals for Diabetes Management. Pharmaceutical Crops 5(1):11-28 2014.

- Syed Saeed ul Hassan2, ShahidRasool, Muhammad Khalil-ur-Rehman, SaiqaIshtiaq, Shahidul Hassan, Imran Waheed& M. Asif Saeed. Phytochemical Investigation of Irritant Constituents of Cuscutareflexa. International Journal of Agriculture & Biology, 14 (5). 3-5 2014.

- UmbaTolo, C., Kahwa, I., Nuwagira, U. . ., Weisheit, A. ., &Ikiriza, H. Medicinal plants used in treatment of various diseases in the Rwenzori Region, Western Uganda. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 25, 1–16. 2023.

- American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 32(Suppl 1): S62–S67.2009.

- Hatem A. Abuelizz,ElHassaneAnouar,Rohaya Ahmad,Nor Izzati Iwana Nor Azman,Mohamed Marzouk,Rashad Al-Salahi. Triazoloquinazolines as a new class of potent α-glucosidase inhibitors: in vitro evaluation and docking studyPlos One14(8): e0220379.2019. [CrossRef]

- Trease, G.E. and Evans, W.C. (1996) A Textbook of Pharmacology. Baillier Tidally, London.

- Inbathamizh L, Padmini E. Quinic acid as a potent drug candidate for prostate cancer—a comparative pharmacokinetic approach. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 6(4):106–1122013.

- Firdous S.M. Phytochemicals for treatment of diabetes. EXCLI Journal 13: 451–453. 2014.

| Phytochemicals | Observations | Conclusion |

| Tannins | ++ | Garlic tannins present |

| Reducing sugars | ++ | Reducing sugars present |

| Anthracenocides | ++ | Anthracenocides present |

| Coumarins | ++ | Coumarins present |

| Saponins | ++ | Saponins present |

| Steroid glycosides | ++ | Steroids present |

| Flavonosides | ++ | Flavanones present |

| Anthocyanins | + | Anthocyanins present |

| Alkaloids | + | Alkaloids present |

| Starch | + | Starch present |

| Phenols | + | Phenols present |

| Amino acids | - | Amino acids absent |

| Anthraquinones | - | Anthraquinones absent |

| Treatment | Fasting Blood Glucose Level, Mean ± SEM (mg/dl) | ||||

| Initial | 5th day | 10th day | 15th day | 20th day | |

| Ext;100mg | 155.7±11.28 | 157.0±11.68 (-0.8) | 157.2±10.73 (-1.0)a | 154.7±8.81 (0.6)c | 167.0±11.50 (-7.2)a |

| Ext;300mg | 148.5±16.04 | 148.2±15.46 (0.2) | 136.7±10.23(7.9)a | 130.5±11.50 (12.1)b | 125.2±2.32 (15.7)a |

| Ext;500mg | 162.2±8.86 | 158.7±9.25 (2.2) | 147.7±7.23 (8.9)a | 132.7±7.86 (18.2)b | 111.2±3.94 (31.5)a |

| PC | 159.5±3.50 | 155.5±3.57 (2.5) | 142.0±2.86 (11.0)a | 121.7±4.27 (23.7)b | 101.7±5.12 (36.2)a |

| NC | 118.0±15.77 | 127.0±213.34(7.6) | 245.0±18.60 (-107.6) | 262.2±44.85 (-122.2) | 251.5±22.50 (-11.3) |

| P value | 0.115 | 0.309 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Group | Number of animals | Dose (mg/kg) | Observations |

| Phase one | |||

| Group one | 3 | 10 | Scratching of the lips |

| Group two | 3 | 100 | Scratching of the lips |

| Group three | 3 | 1000 | Scratching of the lips |

| Phase two | |||

| Group one | 1 | 1600 | Increased breathing rate, Piloerection, Reduced movement |

| Group two | 1 | 2900 | Increased urination, Reduced movement Piloerection, No desire for food & water, Increased breathing rate |

| Group three | 1 | 5000 | Increased urination, Sedation, Increased breathing rate, No movement, Piloerection, No desire for food & water |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).