1. Introduction

According to the latest UN report entitled Measuring digital development Facts and figures 2020 , in Africa, internet use covered 29% of the total population. In the 15-24 age group, this indicator rises to 40%. According to official data from the Multisectoral Regulatory Agency for the Economy (ARME), in 2019 , the internet cover rate in Cape Verde was 73.8%. This is a rapid evolution since in 2014 it was 53.4 %, thus representing an increase of 20.4 percentage points.

According to the National Institute of Statistics , in 2014, 48% of households in Cape Verde had internet, and 67% had it in 2019, representing an increase of 12 p.p. above the average for the African continent. Considering the distinction by gender, according to the same source, 20% of the group of women use the internet, in contrast to 37% of men in Africa. On the other hand, only 3% of the Cape Verdean population admits not knowing what the internet is, being a fringe of the population far from the digital transition process.

The age groups that access the internet the most are 25-34 years old, with 83.7%, closely followed by the 15-24 years of age group with 79.9%, with 78.6% reporting that they use the internet daily. Regarding the time spent daily on the internet, two aspects should be highlighted: only 11.7% say they do so for just one hour, while 63.1% of internet users dedicate five or more hours to surfing the internet.

In terms of technological devices used, internet access is mainly done using mobile phones (96.8%). Cape Verdeans prefer to do it at home (83.5%). A relevant fact that can contribute to a good characterization of the digital transition in Cape Verde is to realize that 16.5% of those who say they do not use the internet say it is due to the high cost, lack of knowledge being the most common reason (46.7%).

Even though with peculiarities, the introduction of the internet into the daily life of Cape Verde and, in particular, its younger age groups, has progressed consistently over the last decade. This paper aims to analyse a society in clear development and how information technologies and especially digital social media are being used and appropriated. It also examines their relationship with violence, especially cyberbullying, by young people in this African archipelago, contributing to a better understanding of a reality that has been the object of repeated neglect by the scientific community.

1.1. Cyberbullying as an Expression of Networked Youth Violence

Digital culture is one of the most expressive features of the youth condition (Nonato, 2020), permeated by an expressive culture of violence (Napoli, 2020). It appears that the question of social class and education (Reis & Sousa, 2017; Bastos & Ferrão, 2019; Marzana et al, 2023) are variables that explain the inequalities in digital literacy levels (Ledesma, 2019), strongly correlated with the phenomenon of cyberbullying (López-Vizcaíno et al., 2021; Singh & Sharma, 2021).

As a violence phenomenon traditionally associated with the school context (Alves, 2016), there was a multiplication and diversification of contexts and circumstances that favour violence among young people. Social media has boosted the growing exposure of its users, particularly younger ones (Akbar & Utari, 2015), with a real tendency to blur the boundaries between the private and public spheres (Sousa & Pinto-Martinho, 2022).

Emma Rich (2024) proposes a reconceptualization of body disaffection among young people, arguing that it should not be understood as an individual pathology, but as a relational phenomenon emerging from intra-actions between bodies, digital technologies and gender norms, generating intense affects such as shame and desire in the context of health and fitness-oriented social networks. Deslandes and Ferreira (2025) show that young Brazilian and Portuguese digital influencers mobilize an incorporated and affective activism on social networks, articulating personal experiences of oppression with discursive strategies of visibility and engagement, challenging hegemonic norms by valuing the stigmatized body as a space of resistance, belonging and political reconfiguration.

This way, with the intensification of interaction in the digital space, the inherent risk of a growing exposure of what is intimacy increases, largely due to social media such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Among young age groups, whether from pre-university or even university education, media consumption is strongly linked to sociability and their own cultural consumption (Nogueira, 2021). The intensive use of smartphones by young people, especially at the weekend, is associated with a significant increase in the risk of anxiety, suicidal ideation and worse mental health assessment (Brodersen, Hammami & Katapally, 2022).

Among the various motivations and appropriations given to digital social media, six axes can be considered from the perspective of Throuvala et al. (2019): 1. facilitating interaction with groups of friends; 2. rapid adoption of various technological devices; 3. emotional management; 4. it plays an important role in the construction of identity; 5. standardization of frames of reference; 6. streamlining and expanding interaction and relationship groups. The effective understanding of the ways in which young people construct the meanings of their use of digital social media allows for more objective and assertive guidance on potential policies and interventions for combating and preventing cyberbullying (Dennehy et al., 2020).

Addiction to social networks in young adults is associated with fear of negative evaluation, which is mitigated by higher levels of self-esteem and conscientiousness (Piko, Krajczár & Kiss, 2024). Violence among young people, especially in the main stages of interaction such as the school context, existed and exists in its most diverse expressions. From this point of view, cyberbullying has acquired relevance and visibility in recent decades, especially considering the increased use of digital platforms, which basically reproduce existing social practices (Kwan & Skorick, 2013). In this perspective, it is essential to see digital practices as important and complex processes of young people’s appropriation of different technological devices.

Greater and more intense participation in digital social media, such as Facebook or Instagram, as a predictor of contact with experiences of online violence is relatively consensual among the scientific community (Cho et al., 2019; Mohseny et al., 2021). Indeed, not only the use of digital social media, in particular Facebook and Instagram, but also the very intensity of this use contributes to the existence of cyberbullying experiences.

Typologically, we can assume that online violence can have the following characteristics in a cumulative or isolated way: insults, devaluation of a class or social nature, pejorative comments, linguistic and image content that hurt the target's susceptibility (Hosseinmardi et al., 2015). Concomitantly, there are authors who point out that repeated practice is a component of online violence, emphasizing its routine nature (Cheng et al., 2019). From the point of view of the intervening actors, online violence is also a type of digital social practice that has young interpreters both as victims and as perpetrators (Moretti & Herkovits, 2021).

Different from the traditional forms of violence where bullying can be included, cyberbullying is enhanced by the permanent access to possible victims about the technological apparatus (Redmond, Lock and Smart, 2020), relativizing the spatial-temporal circumstances. We are therefore able to consider cyberbullying as the repeated and deliberate use of hostile ways of treating third parties to cause them physical and/or moral damage, using technologies that allow communication and measured interaction (Ansary, 2020).

As an area of growing interest, cyberbullying as a research object has been approached from different angles, as summarized by Macaulay et al. (2018): mapping and characterization of cyberbullying; design and implementation of programmes that allow the contribution of knowledge in order to increase digital literacy; institutional awareness of good practices in the prevention and identification of cyberbullying; effort to operationalize the concept of cyberbullying, contributing to its measurement and impact; dissemination of information and knowledge among the actors involved, directly and indirectly, in cyberbullying phenomena.

1.2. The Social Effects of a Youth Culture Permeated by Digital Risks

Regarding the consequences of experiencing cyberbullying situations, it should be noted that there is a very diverse set of implications. In general terms, five categories of actors commonly involved and identifiable in cyberbullying phenomena can be identified: those without involvement; those who testify; those who accumulate the dual role of witness and victim; those who are both a witness and perpetrator; and even witness, victim and perpetrator simultaneously (Yoon et al., 2019).

In this regard, Clark and Bussey (2020) demonstrated that active defence roles for victims and a more reserved behaviour in digital social media is positively correlated with higher levels of empathy and self-efficacy. As advocated by Tokunaga (2010), cyberbullying presents a very diverse set of impacts that go far beyond the psychosocial sphere, negatively impacting, for example, academic achievement, and leading to a higher probability of depression, suicide and family dysfunctions (Chung et al., 2019).

Intensive web browsing and in particular the use of digital social media are also associated with problems of addiction among the younger social categories (Van Ouytsel et al., 2019), negatively impacting psychosocial maturation and growth. The construction of emotions itself is, to a certain extent, conditioned by the experience of cyberbullying (Cho et al., 2019; Balakrishnan et al., 2020), which can be an important instrument to deter and combat this phenomenon. Recently, a survey carried out in South Korea (Lee & Chun, 2020) showed that exposure to cyberbullying, even among young males, had a diverse set of negative consequences, such as: internalizing and externalizing problems, academic failure, erratic management presence on the various online platforms, strategies and practices of self-imposed isolation.

Cyberbullying, as other forms of violence, has social categories that are more likely to be its target. It mainly targets women, even among the university population (Sobba et al., 2017). It is also among the female group that we find those young people who tend to talk and debate in a small circle the cyberbullying situations they know or experience, compared to their male counterparts, who are more limited regarding verbalizing and debating this issue (Livazovic & Ham, 2019). Barker-Clarke (2023) argues that the undifferentiated use of the terms “cyberbullying” and “nudes” by teenage girls contributes to the normalization of digital sexual harassment, particularly through the unsolicited sending of intimate images. This process of trivialization is the result of a digital gender habitus shaped by post-feminist dispositions and the absence of effective institutional responses.

The possibility of greater risk to cyberbullying corresponds to a greater risk of being a victim of some type of violence, which we will call digital vulnerability. Digital vulnerability corresponds to higher levels of risk of cyberbullying, which, in some categories, such as women, has potential targets. It can also be approached from the point of view of gender power relations.

Academic literature has reported a greater propensity of females to experience situations of bullying (Guimarães & Cabral, 2019) and cyberbullying (Coelho & Romão, 2018; Ndvave and Kyobe, 2019; Gomes Barbosa et al., 2024). However, there are recent surveys (Mohseny et al., 2021) that demonstrate opposite trends, that is, among a population of pre-university school level it was found that male respondents showed a higher level of contact and frequency with situations of cyberbullying. Female respondents made fewer complaints. This empirical observation is, nevertheless, due to nuances of a cultural nature and to the idiosyncrasies of the communities and societies in which the research is carried out. In practice, we can be faced with a culture that allows a group, whether male or female, to express greater sensitivity to situations of violence and, more specifically, to cyberbullying.

Considering the domain of digital practices studies, there are some indicators that allow establishing some predictive capacity regarding the occurrence of cyberbullying situations in the use of digital tools that involve risk, but also a certain moral fluidity, in addition to those who traditionally are victims of bullying (Chen et al., 2017). At the same time, recent surveys that measure the intensity of internet usage daily can demonstrate that there is effectively a correlation between increased internet usage and higher levels of digital vulnerability (Choi et al., 2019). Among these social categories composed of young people, it was found that they are cumulatively those that are more exposed on digital social media, namely their lifestyles or leisure activities (Muller et al., 2018), although we are far from a consensus among researchers regarding this association (Camerini et al., 2020).

WhatsApp, as one of the most popular digital social media among the most diverse age groups, provides immediate connectivity and easy access to co-workers, friends or family (Rey et al., 2019; Symons et al., 2018). It is reported as a stage for cyberbullying, where there are repeated verbal offenses, exclusion of actors from interaction groups and image attacks, as well as constraints on the expression of one's own opinion (Aizenkot, 2020). Dating or maintaining an intimate online interaction (sexting) is also a very recurrent element in cyberbullying (Van Ouytsel et al., 2019). Also, the abundant use of emojis, as symbols of expression of emotions and reactions, is also part of an online circumstance framework in which their authors may be victims of cyberbullying (Matulewska & Gwiazdowicz, 2020).

Thus, the question is: to what extent the use and appropriation of digital social media is conditioned by the perception and experience of cyberbullying situations? The theoretical evidence allows us to equate the following research hypothesis for our work: H – The use and appropriation of digital social media by young Cape Verdeans is associated with the perception and experience of cyberbullying phenomena.

2. Materials and Methods

The field work was carried out at the Public University of Cape Verde (UNI-CV) in November and December 2019. The survey was conducted directly and in person and completed by the respondents themselves. It had an average duration of 15 minutes. The survey consisted of twenty-six indicators, grouped along the following lines: social, demographic and family characteristics; digital practices; risks and vulnerabilities in the digital sphere. Through a non-probabilistic convenience sample (Marôco, 2010), a sample of 349 students who attended public higher education at the University of Cape Verde, on the Palmarejo campus (city of Praia), was obtained. Of those, 255 were validated for the construction of clusters, resulting in a convenience sampling. Data were analysed using SPSS version 28.

2.1. Analysis Model and Measures

Four indicators were considered: Q12 – online practices and presence ; Q16 – profile on social media ; Q19 – privacy settings and Q21 – changing privacy criteria . This procedure enabled us to categorize the young people surveyed regarding their attitudes towards visibility in digital social media, allowing us to articulate theoretical dictates with methodological and technical rigor. By articulating not only digital practices, but also provisions relating to the management of digital social media, this model enables a better understanding of the topic under study.

As for the variables of social and demographic characteristics, sex was coded as follows; 0 - female and 1 - male. The quantitative variable age was measured according to the number of years. The daily internet use was also measured according to the number of daily hours reported by each respondent. We also considered the educational qualifications of the respondents' parents . Using the Spearman-Brown measure of association of 0.83, we built a composite index that synthesizes the qualifications of the parents. Regarding digital practices, it resulted in a composite index of 24 items with a Cronbach's α of 0.83, which goes from 1 (never) to 5 (every day). Third-party cyberbullying is also an index composed of seven initial items; 1- Yes and 2 – No. With a 0.75 association measure (Cronbach α). In this line, the cyberbullying experienced by the respondent also results from the association of eight initial items with a Cronbach α of 0.66 (Cohen, 1992) and coded with 1- Yes and 2 – No.

2.2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The analysis model focuses on cluster analysis, initially hierarchical and then non-hierarchical. This statistical model of association allows us to categorize cases with relative similarities and distinguish them from those that differ, using considered criteria (variables). In the case of this analysis, which is exploratory in nature, it allows us to identify different provisions regarding privacy practices in digital social media, as well as the management of their presence on these platforms. In this sense, the hierarchical cluster model was implemented (Marôco, 2010). To this end, the between-groups linkage method was defined as an aggregative model and since the four variables that operationalize the definition of clusters have quantitative scales, the squared Euclidean distance measure was chosen.

From the analysis of the dendrogram, two large clusters stand out. We can see two sets that dominate the categorization of respondents. The first, in the upper component of the dendrogram, still presents great internal heterogeneity. The second, represented by the lower half of the diagram, also has a considerable dimension. Thus, we need to advance a step in the distribution of cases and thus opt for four clusters. Of these, two stand out due to their larger size and two are smaller, although substantively there are differences between the four.

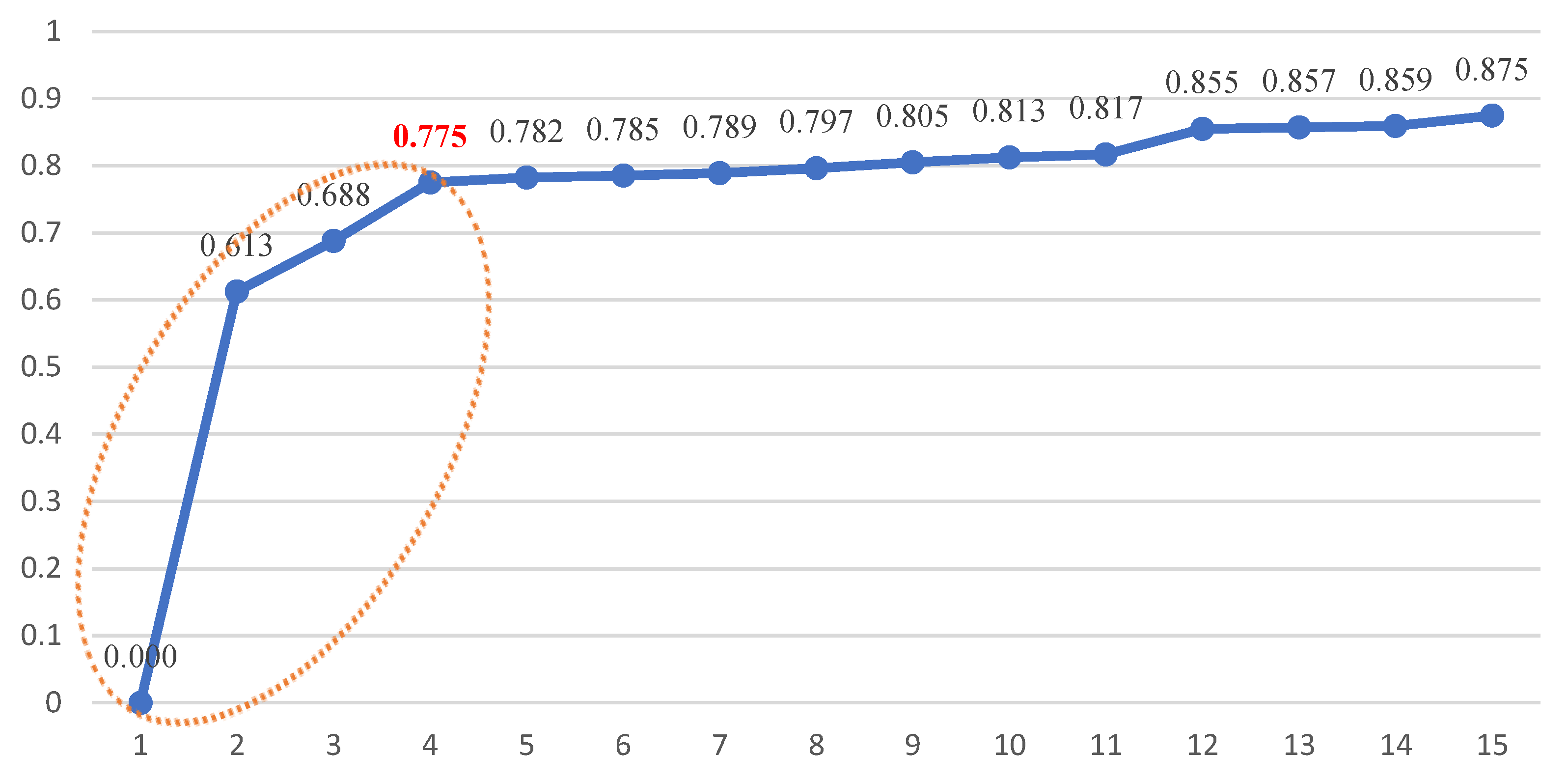

The choice of four clusters proved to be fruitful, given the results shown in

Figure 1. The footnote of the SPSS output mentions that individuals were assigned to the first, with no significant variation in the respective centroids. Furthermore, the four-cluster model guarantees the explanation of 77.49% (R-sq = 0.78) of the total variance.

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the R2 criterion, simulating the variance explained by the different solutions, up to a maximum solution of fifteen clusters. In this sense, it is noticeable, due to the loss of inclination of the straight line, which becomes progressively parallel to the horizontal axis, that a solution with four clusters is the most appropriate. Moving to a solution with five clusters does not substantively add to the variance explained by the model. However, the transition from three to four clusters has increased explanatory power.

2.3. Non-Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The four indicators were standardized, given the existence of different scales among the four indicators used, to mitigate the possibility that those with greater amplitude could impact the discrimination of the four clusters that make up the final solution. With this procedure, the four indicators are placed with the same possibility of configuring the four clusters. Thus, the calculation of the F statistic was carried out to quantify the weight of each indicator in distinguishing the clusters: variable Q21 records a statistic of F = 1142.67. The remaining variables: Q12 = 224.13, Q16 = 0.80 and Q19 = 9.63. In fact, variable Q21 is the one with the greatest differentiating weight and defining capacity of the four clusters. It should be noted that the way in which the variables are constructed allows for a more readable and intuitive interpretation of the data, since they operationalize an increasing order in all four indicators that are above.

3. Results

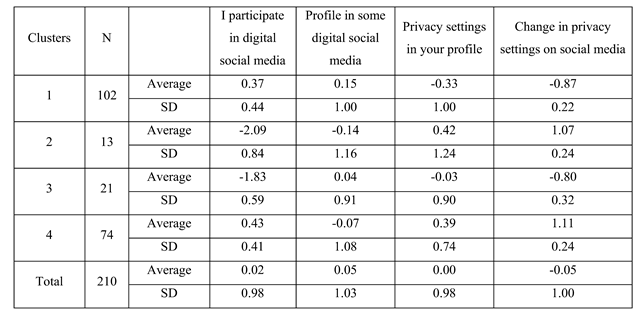

We measured the level of association of the four indicators that make up the presented cluster model , which resulted in the following distribution of cases: cluster 1 = 29%; cluster 2 = 6.2%; cluster 3 = 48.6%; cluster 4 = 10%.

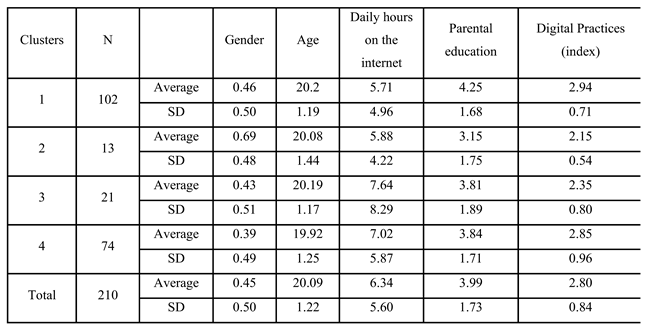

The initial sample consists of 255 respondents, 210 of which are part of the construction of clusters (Table 1). This disjunction refers to cases of non-responses in one or more of the four items. Among those validated, 57% are female with a mean age of 20 years (SD = 1.21) with ages ranging between 18 and 22 years. On average, the young Cape Verdeans surveyed use the internet for approximately 6 hours (SD = 5.55) per day. Parental education indicates a medium level (7th to 9th grade) (measure 1-6) when the average is 4.03 (SD=1.75).

Digital practices in general present a frequency of 2.94, which can be interpreted as a value below the median value (measure 1-5) (SD = 0.92). With regard to measuring cyberbullying, the experiences reported by friends or relatives of the respondents were distinguished from those experienced by the respondents themselves. A greater number of cyberbullying situations experienced by people in their personal sphere is reported (X = 0.5; SD = 0.31), compared with those experienced by the respondents themselves (X = 0.35; SD = 0.24).

Females are more likely to experience cyberbullying situations, either through knowledge of family or friends (X = 0.52; SD = 0.31), or through their own experience (X = 0.36; SD = 0.24). For the male group, the records are respectively lower: X = 0.48; SD = 0.31 and X = 0.34; SD = 0.24. The execution of different practices in a digital context follows the same trend, with the group of young women reporting higher frequency (X= 3.00; SD = 0.93), compared with the male group (X = 2.90; SD = 0 .93). The female group also spends more time daily using the internet (X = 6.78; SD = 6.40), compared with their male counterparts (X = 5.36; SD = 3.72), which means almost another hour and a half.

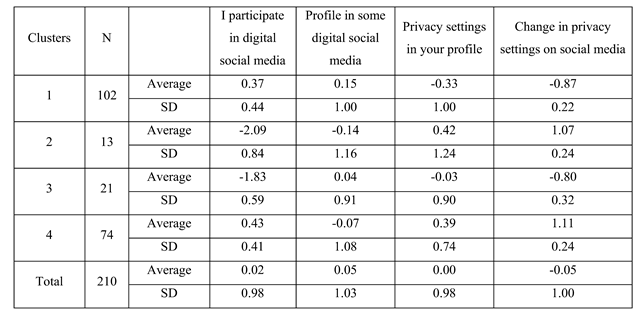

The clusters make it possible to distinguish ways of managing the participation of the young people in online social media. Briefly, we would say that cluster 1 stands out for grouping respondents who adopt practices of greater control of visibility through greater selectivity of who can access their profile on social networks.

Cluster 2 brings together young Cape Verdeans who use digital social media less and who also have less presence in them. The third cluster brings together a group of young people interviewed who do not differ in any of the four criteria considered, demonstrating that they have practices within the total average values. Finally, the fourth cluster gathers those who differ from the others due to the intense presence in digital social media and for not having marked practices of restriction of access to their digital social media (see Table 2).

Table 2. Cluster averages in the four indicators

Note: Standardized variables. Source: Authors’ own.

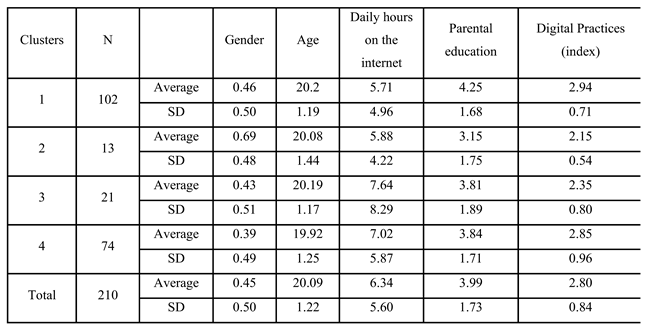

The male group is the majority only in cluster 2, which is distinguished by its lower presence on digital platforms, and which tends to change the settings in order to obtain greater privacy (according to Table 3).

Table 3. Descritive statitics of the variable by cluster.

Source: Authors’ own.

In the remaining three categories, women are in the majority, with emphasis on the fourth cluster with 61%, which stands out due to the intense involvement in digital social media and the scarce change in privacy settings. The four clusters do not differ in terms of average age, all of them being around 20 years old. The daily time dedicated to internet use is a differentiating factor, since cluster 3 spends approximately 8 hours a day on the internet, while cluster 4 spends 7 hours. On the opposite side, we find clusters 1 and 2 that respectively use 6 of their daily hours browsing the internet. Parental education is approximately between the 7th and 9th grades of schooling across the four clusters.

Finally, about the frequency of practices in the digital space, clusters 1 and 4 spend more time, in contrast to clusters 2 and 3, which have lower digital practices.

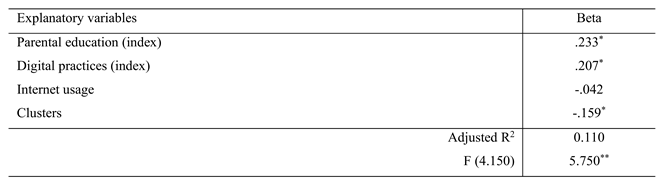

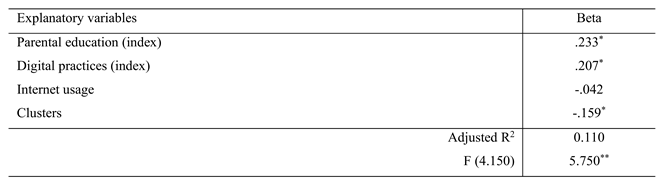

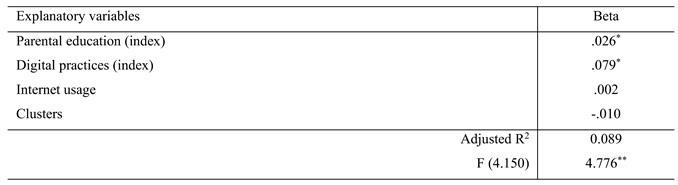

After verifying the assumptions[1], a linear regression model was used (cf. Table 4 and Table 5) [2][3], which allows measuring the predictive capacity of the two cyberbullying indicators. The constructed models enable explaining, respectively, 11% and 9% of the variance of cyberbullying, sometimes experienced by third parties, sometimes experienced by the respondents themselves. Regarding the identification of cases of online violence directed at friends or relatives, parental education and digital practices, besides having a statistically significant effect, are also positive, that is, as the educational qualifications of the two parents increase, the greater the incidence of cases of digital violence against family and friends. The same happens with digital practices, the greater the digital practices, the more knowledge about cyberbullying situations on third parties is revealed.

In clusters, if there is a statistically significant effect, it is negative. This means that as one moves from the first cluster to the fourth, the incidence of this type of violence tends to decrease.

Table 4. Explanatory factors of cyberbullying experienced by third parties (multiple regression).

P=0.05* p=0.001** Source: Authors’ own

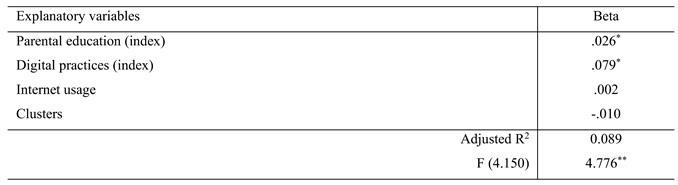

Cyberbullying experienced by the respondents themselves (cf. Table 5) shows trends that are relatively in line with those described above (cf. Table 4). Both parents' education and digital practices have significant and positive effects, translating into an increase in the declaration of having been, at some point, a victim of online violence. Clusters do not have a statistically significant effect, and are negative, in line with what was seen regarding cyberbullying experienced by third parties.

Table 5. explanatory factors of cyberbullying experienced by the respondents (multiple regression).

P=0.05* p=0.001** Source: Authors’ own.

In a provisional balance, in addition to the level of education of parents being a good predictor, as well as increased digital practices, in clusters 3 and 4 there are greater signs of denunciation of experiences of cyberbullying in its different aspects.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

The empirical evidence revealed some social and cultural contours that may explain the phenomenon of cyberbullying and its complex understanding. In general, young people´s use of the internet is seen as intense and, above all, for purposes of leisure and promotion of sociability. With this intense and almost permanent submersion in the digital sphere, contact with situations of violence tends to reflect this increase. We sought to understand which strategies are constructed by young Cape Verdean respondents with regard to their participation in digital social media and how these are associated with the perception and experience of cyberbullying situations.

The first two clusters categorize the young Cape Verdeans who adopt a more precautionary stance when browsing digital social media. The first is based on a proactive stance, by changing the privacy settings on their accounts and profiles on these websites. On the other hand, we would say that the second cluster is cautious but adopting a posture (deliberate or not) that tends to be passive, with less participation and less use of digital social media: this cluster has a smaller number of profiles and accounts in this type of platforms. In contrast, the young members of the fourth cluster distinguish themselves from the others because they are avid users of digital social media and because they have an account on various websites, without any restriction on their access and shared information.

Thus, we would say that the active cautious (cluster 1) come from a family background where there are greater educational resources for parents, which is also reflected in more diversified digital practices, which go far beyond digital social media.

Those who are cautious due to inertia (cluster 2) are mostly male and come from family members that tend to have low levels of education. They do not spend much time on the internet on a daily basis and have low levels of frequency of digital practices, i.e., little diversity beyond the use of digital social media.

The attitudinal polarization is found in cluster four, which adopts a very relaxed posture regarding the management and access to their information shared in the profiles of digital social media. At the same time, it is also the group that most declare to visit these digital platforms, which we will designate as active carefree.

Some of the social determinants tested add explanatory power to the implemented model. The most paradigmatic case is parental education. We noticed that it is decisive in the proximity and access of young Cape Verdeans to digital social media, as in the cases of clusters one and four. Both the active cautious and the active carefree show great ease in accessing, handling and diversity in the use of the internet. After all, the highest levels of cyberbullying are found primarily in the active cautious with cyberbullying experienced by third parties (X=0.57; SD=0.30) and cyberbullying experienced by themselves (X=0.38; SP=0. 23). These findings are close to those seen among the active carefree with respectively X= 0.48 (SD=0.31) and X=0.34 (SD=0.24). Additionally, the cautious due to inertia register the lowest values of cyberbullying in their versions: experienced by third parties X=0.41 (SD=0.31) and experienced by themselves X=0.30 (SD=0.19).

These data contribute to the idea that there is an association between digital activity, parents' educational level and the perception of contact/proximity with cyberbullying. On the contrary, less contact with this type of online violence is associated with low educational levels of parents, as well as a more sporadic and even suspicious contact with the internet in general. Indeed, we have enough empirical evidence to see that the perception of cyberbullying is greatly conditioned by sociocultural circumstances, such as the educational qualifications of the parents, which are the starting point for a circumstantial framework that conditions what is done, but also the management strategies on digital social media (Carriço dos Reis et al., 2018). Emotional and behavioural self-regulation is a significant protective factor against the perpetration of bullying, including cyberbullying, during early adolescence (Williams et al. 2024). In fact, self-regulation skills should be strengthened to enhance the prevention of bullying among young people. On another front, as Pivec (2024) suggests, there is the possibility that brief school interventions, guided by the principles of positive youth development (the Five Cs: competence, confidence, character, care and connection), can indirectly influence the reduction of bullying and victimization, especially when they promote a sense of connection between peers in adverse contexts.

Of course, this reflection does not have totalizing ambitions regarding knowledge about the reality of Cape Verdean youth. There are still some “loose ends”, such as the cases, for example, of the active cautious. Did they adopt a proactive stance of relative security after experiences with cyberbullying? Or does this posture reflect full awareness of the risk they are running? This is the type of question that did not fit in this analysis, but that could potentially be part of future research, whether quantitative or qualitative.

Author Contributions

(redacted for peer review).

Funding

(redacted for peer review).

Institutional Review Board Statement

(redacted for peer review).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aizenkot, D. (2020). Cyberbullying experiences in classmates‘ WhatsApp discourse, across public and private contexts. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104814. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M. A., & Utari, P. (2015). Cyberbullying pada Media Sosial (Studi Analisis Isi tentang Cyberbullying pada Remaja di Facebook). Journal Komnas, 1, 1–20.

- Alves, M. G. (2016). Viver na escola: indisciplina, violência e bullying como. desafio educacional. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 46(161), 594–613. [CrossRef]

- Ansary, N. S. (2020). Cyberbullying: Concepts, theories, and correlates informing evidence-based best practices for prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101343. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V., Khan, S., & Arabnia, H. R. (2020). Improving cyberbullying detection using Twitter users’ psychological features and machine learning. Computers and Security, 90. [CrossRef]

- Barker-Clarke, E. (2023). Girls navigating the context of unwanted Dick Pics: ‘some things just can’t be unseen.’ Youth, 3(3), 935–953. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A., & Ferrão, M. E. (2019). Analysis of grade repetition through multilevel models: A study from Portugal. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 49(174), 270–288. Camerini, A., Marciano, L., Carrara, A., & Schulz, P. J. (2020). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among children and adolescents: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Telematics and Informatics, 49, 101362. [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K., Hammami, N., & Katapally, T. R. (2022). Smartphone use and mental health among youth: It is time to develop smartphone-specific screen time guidelines. Youth, 2(1), 23–38. [CrossRef]

- Carriço dos Reis, B. M., Rivera Magos, S., Lopes, P., & Sousa, J. (2018). Prácticas digitales de los jóvenes portugueses y mexicanos. Un estudio comparativo. index.comunicación, 8(3), 207–227.

- Chen, L., Ho, S. S., & Lwin, M. O. (2017). A meta-analysis of factors predicting cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: From the social cognitive and media effects approach. New Media and Society, 19(8), 1194–1213. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. , Guo, R., Silva, Y., Hall, D., & Liu, H. (2019). Hierarchical attention networks for cyberbullying detection on the Instagram social network. In SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, SDM 2019 (pp. 235–243). Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Publications. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., Lee, H., Peguero, A. A., & Park, S. (2019). Social-ecological correlates of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration among African American youth: Negative binomial and zero-inflated negative binomial analyses. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 50-60. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K. S., Cho, S., & Lee, J. R. (2019). Impacts of online risky behaviors and cybersecurity management on cyberbullying and traditional bullying victimization among Korean youth: Application of cyber-routine activities theory with latent class analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chung, T. W., Sum, S. M., & Chan, M. W. (2019, June 1). Adolescent Internet Addiction in Hong Kong: Prevalence, Psychosocial Correlates, and Prevention. Journal of Adolescent Health. Elsevier USA. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M., & Bussey, K. (2020). The role of self-efficacy in defending cyberbullying victims. Computers in Human Behavior, 109. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V. A., & Romão, A. M. (2018). The relation between social anxiety, social withdrawal and (cyber)bullying roles: A multilevel analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, R., Meaney, S., Walsh, K. A., Sinnott, C., Cronin, M. & Arensman, E. (2020). Young people’s conceptualizations of the nature of cyberbullying: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51, 101379. [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, S. F., & Ferreira, V. S. (2025). Connective embodied activism of young Brazilian and Portuguese social media influencers. Youth, 5(1), 28. [CrossRef]

- Gomes Barbosa, M. P., Blanco-Herrero, D., Arcila-Calderón, C., & Sánchez-Holgado, P. (2024). Discurso de ódio na Espanha. Pesquisa sobre a percepção e a experiência da população. Observatorio (OBS*), 18(2). [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J. & Cabral, C. S. (2019). Bullying entre meninas: tramas relacionais da construção de identidade de gênero. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 49(171), 160–179. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinmardi, H. , Mattson, S. A., Rafiq, R. I., Han, R., Ly, Q., & Mishra, S. (2015). Analyzing Instagram cyberbullying incidents on the Instagram social network. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) (Vol. 9471, pp. 49–66). Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, G.C., & Skoric, M.M. (2013). Bullying no Facebook: uma extensão das batalhas na escola. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (1), 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, A. E. (2019). Escuela y medios digitales: algunas reflexiones sobre el proyecto transmedia literacy. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 49(174), 222–245. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Chun, J. S. (2020). Conceptualizing the impacts of cyberbullying victimization among Korean male adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 117. [CrossRef]

- Livazovic, G. & Ham, E. (2019). Cyberbullying and emotional distress in adolescents: the importance of family, peers and school. Heliyon, 5(6). [CrossRef]

- López-Vizcaíno, M. F., Nóvoa, F. J., Carneiro, V., & Cacheda, F. (2021). Early detection of cyberbullying on social media networks. Future Generation Computer Systems, 118, 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, P. J. , Betts, L. R., Stiller, J., & Kellezi, B. (2018). Perceptions and responses towards cyberbullying: A systematic review of teachers in the education system. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2010), Análise Estatística com o PASW Statistics (ex-SPSS), Pero Pinheiro, reportnumber.

- Marzana, D., Ellena, A. M., Martinez-Damia, S., Ribeiro, A. S., Roque, I., Sousa, J. C., Agahi, O., Pell Dempere, M. I., & Prieto-Flores, Ò. (2023). Public Employment Services and strategic action towards rural neets in Mediterranean Europe. Social Sciences, 13(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Matulewska, A., & Gwiazdowicz, D. J. (2020). Cyberbullying in Poland: a case study of aggressive messages with emojis targeted at the community of hunters in urbanized society. Social Semiotics, 30(3), 379–395. [CrossRef]

- Mohseny, M., Zamani, Z., Basti, S. A., Sohrabi, M. R., Najafi, A., & Tajdini, F. (2021). Exposure to cyberbullying, cybervictimization, and related factors among junior high school students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C., & Herkovits, D. (2021). Victims, perpetrators, and bystanders: A meta-ethnography of roles in cyberbullying. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 37(4). [CrossRef]

- Muller, C. R., Pfetsch, J., Schultz-Krumbholz, A., & Ittel, A. (2018). Does media use lead to cyberbullying or vice versa? Testing longitudinal associations using a latent cross-lagged panel design. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 93–101. [CrossRef]

- Napoli, P. N. (2020). Sociabilidades violentas no conflictivas entre estudiantes de escuelas medias. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 50(176), 605–621. [CrossRef]

- Ndyane, Z. C. , & Kyobe, M. (2019). Mobile Bully-victim Behaviour on Facebook: The case of South African Students. In 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference, IEMCON 2019 (pp. 743–749). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, M. A. (2021). O capital cultural e a produção das desigualdades escolares contemporâneas. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 51. [CrossRef]

- Nonato, E. R. (2020). Cultura digital e ensino da literatura na educação secundária. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 50(176), 534–554. [CrossRef]

- Piko, B. F., Krajczár, S. K., & Kiss, H. (2024). Social media addiction, personality factors and fear of negative evaluation in a sample of young adults. Youth, 4(1), 357–368. [CrossRef]

- Pivec, T. (2024). Supporting the five Cs of positive youth development amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact on adolescents’ bullying behaviour. Youth, 4(1), 191–213. [CrossRef]

- Redmond, P., Lock, J. V., & Smart, V. (2020). Developing a cyberbullying conceptual framework for educators. Technology in Society, 60. [CrossRef]

- Reis, B. C., & Sousa, J. C. (2017). A Invisibilidade do desemprego (juvenil) no Discurso Mediático da imprensa portuguesa. Observatorio (OBS*), 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Rey, R. D. , Ojeda, M., Casas, J. A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Elipe, P. (2019). Sexting among adolescents: The emotional impact and influence of the need for popularity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(AUG). [CrossRef]

- Rich, E. (2024). A new materialist analysis of health and fitness social media, gender and body disaffection: "You shouldn’t compare yourself to anyone... but everyone does". Youth, 4(2), 700–717. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. , & Sharma, S. K. (2021). Review of Machine Learning methods for Identification of Cyberbullying in social media. In Proceedings – International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems, ICAIS 2021 (pp. 284–288). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [CrossRef]

- Sobba, K. N., Paez, R. A., & Bensel, T. (2017). Perceptions of Cyberbullying: An Assessment of Perceived Severity among College Students. Tech Trends, 61(6), 570–579. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J. C., & Pinto-Martinho, A. (2022). Confiança e Uso dos media na União Europeia. Media & Jornalismo, 22(41), 161–178. [CrossRef]

- Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2018). Sexting scripts in adolescent relationships: Is sexting becoming the norm? New Media and Society, 20(10), 3836–3857. [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M. & Kuss, D. J. (2019). Motivational processes and dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use among adolescents: A qualitative focus group study. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 164–175. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J., Lu, Y., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Temple, J. R. (2019). Longitudinal associations between sexting, cyberbullying, and bullying among adolescents: Cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 73, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C., Griffin, K. W., Botvin, C. M., Sousa, S., & Botvin, G. J. (2024). Self-regulation as a protective factor against bullying during early adolescence. Youth, 4(2), 478–49. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y., Lee, J. O., Cho, J., Bello, M. S., Khoddam, R., Riggs, N. R., & Leventhal, A. M. (2019). Association of Cyberbullying Involvement With Subsequent Substance Use Among Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(5), 613–620. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).