1. Introduction

Modern cosmology rests on the empirically successful

-CDM model, describing an expanding Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker universe [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, this observational success masks a profound conceptual tension known as the “problem of time”—the fundamental difficulty of reconciling apparent cosmic evolution with general relativity’s block universe consequence [

5,

6,

7]. This tension emerges from the conflict between mathematical

eternalism, which posits that the universe’s 4D geometry is fully realized at once [

8,

9,

10], and the physical experience of temporal becoming observed by embedded cosmic observers.

1.1. The Missing Transport Field: Spacetime Diffusivity

A fundamental gap exists in our field-theoretic description of information transport through spacetime. While physics has well-established transport fields—thermal diffusivity

for heat transport, kinematic viscosity

for momentum transport, and Einstein’s Brownian diffusion coefficient

D with dimensions

for particle transport [

11]—no corresponding field describes information transport between temporal layers of spacetime itself.

This omission becomes critical when considering that

all physical interactions fundamentally involve information transfer. Quantum information theory reveals that every physical process operates as a quantum channel with capacity limited by environmental decoherence [

12,

13], Lieb-Robinson bounds on entanglement spreading [

14,

15], holographic area constraints [

16,

17,

18], and Landauer’s principle enforcing energetic costs for information processing [

19].

These considerations mandate a fundamental field with dimensions quantifying the irreducible spread in accessibility, precision, and localization of information about the universe’s state. This “spacetime diffusivity” field extends Einstein’s insight that transport phenomena are governed by diffusivity fields: just as thermal diffusivity emerges from molecular chaos, arises from quantum-informational uncertainty at the Planck scale that propagates coherently across all scales. Perfect localization of information flow (energia fluens) at any cosmological point inevitably comes at the cost of losing precision in gravitational aspects like mass (energia locata).

1.2. Quantum Measurement Incompatibility in Cosmological Observations

Recent advances in astronomical precision reveal an unexpected pattern: measurements requiring high temporal resolution for signal dispersion analysis systematically yield different mass estimates than measurements optimized for gravitational effects. Every astronomical photon must simultaneously encode both source properties (mass distribution, velocity dispersion) and propagation effects (temporal broadening, spectral line widening). The finite capacity of photon ensembles creates unavoidable resource competition between these observational goals, suggesting fundamental uncertainty relations between spacetime transport properties and mass content that extend traditional quantum mechanics to cosmological measurements.

1.3. Foundational Postulates and Scale Unification

We adopt a foliated block universe perspective, treating the universe as a sequence of information layers indexed by parameter s. This bridges eternalist (static 4D manifold) and presentist (observed temporal flow) perspectives through finite information propagation constraints. Our approach explores two minimal postulates:

Postulate 1 (Invariant Time-like Information): Causal structure enforces information propagation at the fundamental rate:

Postulate 2 (Diffused Spacetime): A spacetime diffusivity field with dimensions evolves according to:

Through canonical quantization of the resulting first-order action , we derive the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle: , establishing quantum conjugacy between spacetime diffusivity and mass content.

Our central theoretical breakthrough extends this through

Information-Pixel Amplification: spacetime pixelates into coherence cells of scale

where quantum decoherence dominates [

13,

20,

21]. Signals traveling distance

D sample

independent pixels, each contributing minimal action uncertainty

, yielding the

amplified constraint:

This framework generates four principal results: (1) Quantum-gravitational parametric unification—both Planck time and Hubble time emerge from a single diffusion parameter across 60 orders of magnitude; (2) Enhanced cosmological temperature—fundamental thermal limit K exceeding classical Gibbons-Hawking temperature; (3) Quantitative dark matter predictions—exact reproduction of Milky Way uncertainties ( kg) using FRB-motivated diffusivity parameters; (4) Resolution of temporal ontology—apparent time flow emerges from scale-invariant informational constraints on embedded observers.

The framework reveals that quantum uncertainty constraints operating through spacetime diffusivity generate fundamental connections between quantum mechanics, information theory, and cosmic structure, offering testable predictions for precision-uncertainty trade-offs in astronomical measurements while providing fresh perspectives on foundational questions spanning from quantum gravity to observational cosmology.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Spacetime Framework and Information Transport

From the external eternalist perspective, the universe emerges as a static, time-like informational manifold where “time” represents information propagation between successive invariant layers rather than fundamental temporal flow.

2.1.1. Time-like Structure from Causal Constraints

For a universe emerging from a finite past boundary—as required by Borde–Guth–Vilenkin (BGV) arguments [

22]—we consider the limiting case where all separations become purely time-like. Constraining analysis to causal intervals:

and taking the idealized limit

yields:

This suggests a foundational relationship:

Theorem 2.1 (Invariant Time-like Information Postulate)

. Under BGV constraints with , the informational structure enforces:

where s parameterizes the informational stratification built into the eternal manifold structure.

Proof. Direct consequence of causal structure in the time-like universe. □

Invariant Foliation Time

We work with a global foliation

(later chosen as

slices). The label

t is defined

intrinsically from the scalar effective light-cone area accumulated up to

:

Because

is built from causal structure and areas,

t is an invariant foliation label. In a discrete picture with slice indices

, one has

with each

fixed by the same geometric rule; hence

is invariant.

Claim

For timelike progression with , the invariant label satisfies .

Reason. In the local rest frame . Our normalization makes equal increments of t correspond to equal increments of , implying up to the fixed normalization; therefore .

The parameter t labels successive information layer hypersurfaces in the eternal foliation, representing a classical foliation coordinate (not a quantum operator) that indexes the static stratification. This avoids operator-ordering ambiguities since t serves as a geometric parameter indexing information layers , while quantum operators and act within each hypersurface rather than between layers.

2.2. Physical Interpretation of Time-like Layers and Emergent Dynamics

We foliate spacetime into a sequence of

information layers , each labelled by the length-like parameter

. In the limit

these hypersurfaces are spacelike, and their timelike normal advances through the foliation according to the universal conversion rule

with

t the

invariant foliation label defined in Def. 2.1.1.1. In local rest frames one has

and our normalization

identifies

t with

up to a constant, so

(Claim 2.1.1.2).

Physical meaning. Globally the universe is a static 4-D block; apparent temporal flow reflects the finite rate at which observers acquire information. A layer contains everything causally accessible up to the depth s (equivalently, up to proper time ). Moving to corresponds to a clock tick of .

Emergence of ordinary physics. Spatial structure and local dynamics are encoded within each layer, while apparent evolution arises from correlations between neighbouring layers. When the stack is projected onto standard spacetime coordinates, it traces observer-dependent world-histories: motion, field evolution, and cosmic expansion appear as successive updates of information.

Spatial variations and expansion. Each is a complete spatial slice (we later choose for symmetry). As s increases—i.e. further from the initial singularity—each layer contains more causal data; to an internal observer this reads as cosmic expansion and growing spatial complexity.

Relation to observation. Observers, confined to their past light cones, follow trajectories normal to the foliation. Although the block as a whole is timeless, all familiar processes—particle motion, structure formation, and expansion—emerge from how information layers are successively accessed.

Thus the framework reconciles a static block universe with the felt arrow of time by tying apparent dynamics to the finite-speed acquisition of information.

Remark 2.1 (Cosmic Flip-Book Analogy). The temporal layer structure can be visualized as a cosmic flip-book: each information layer represents a static “page” containing the complete 3D spatial configuration at one moment, while the classical time parameter t serves merely as the “page number.” The quantum operators and correspond to “drawings on each page”—acting within individual layers without crossing between them. The universal conversion rule determines the “flipping speed” through the sequence. Crucially, while each page remains eternally static (preserving the block universe), the sequential accessing of pages by embedded observers creates the illusion of temporal flow, naturally resolving the problem of time through finite information propagation constraints.

2.2.1. Mathematical Formalization

We model the universe as stratified informational layers (see Remark 2.3) indexed by parameter s, each possessing finite information-carrying capacity . For computational tractability, we represent these layers using 3-sphere foliation:

Let

be an interval of the time-like parameter

s, and let:

be a smooth radius function, where

represents the maximal informational boundary radius [

23,

24].

Definition 2.1 (Informational Layer)

. For each , define the informational layer

as the embedded 3-sphere:

The total informational manifold becomes:

equipped with the pullback of the Euclidean metric on [3,25].

Remark 2.2 (3-Sphere Structure Justification). We adopt 3-sphere foliation based on several considerations:

Maximal symmetry: No preferred directions, ensuring informational isotropy

BGV consistency: Closed geometry accommodates required past boundaries

Finite information capacity: Bounded information content per temporal slice

Computational tractability: Well-defined boundaries for flux calculations

Observational compatibility: Current CMB constraints permit slight positive curvature

Wave-equation symmetry: Maxwell’s equations yield spherical solutions ensuring uniform information propagation [26]

Huygens–Fresnel principle: Spherical wavelet reconstruction preserves isotropy [27]

Theorem 2.2 (Temporal Layer Uniqueness). Each informational layer in the foliated universe is unique and contains distinct information content.

Proof. Consider two distinct parameter values . The corresponding layers and are unique for several reasons:

1. Capacity Differentiation: From the DTP (), the diffusivity field evolves continuously, implying for . This creates distinct information transport capacities between layers.

2. Information Content Evolution: Each layer has maximum information capacity . Since varies with s, different layers have different information storage capabilities.

3. Causal Ordering: The constraint establishes strict causal ordering between layers. Information can only propagate from layer to layer if , creating asymmetric temporal relationships that distinguish each layer uniquely.

4. Observer Accessibility: Observers in layer s can only access information from previous layers , creating unique epistemic contexts for each layer. □

Remark 2.3 (Cosmic Onion Structure). The 3-sphere foliation resembles a cosmic onion : each informational layer with radius forms a concentric spherical shell around all previous layers. As the parameter s increases from the initial boundary, successive layers expand outward like onion layers, with all shells sharing a common center corresponding to the Big Bang singularity. This nested structure naturally encodes the causal hierarchy where information from inner layers (earlier times) can influence outer layers (later times), but not vice versa, preserving the temporal ordering essential for cosmic evolution while maintaining the spherical symmetry that ensures no preferred spatial directions in the universe’s expansion.

2.3. Physical Rationale for the Two Postulates

We elevate two statements to axioms:

[Invariant foliation flow] The invariant line element grows linearly with the invariant foliation label

t (Def. 2.1.1.1):

[Spacetime-diffusivity] There exists a Lorentz-scalar field

with units

such that

Axiom 2.1 is the usual proper-time normalisation familiar from special relativity. Axiom 2.2 generalises Einstein’s Brownian coefficient (see [

11]) from matter to spacetime itself; cf. Caianiello’s maximal acceleration [

28], holographic transport bounds [

29], and stochastic-gravity approaches [

30]. Taken together, (i) and (ii) are the

minimal ingredients from which the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (CUP) follows (

Section 2.6.2). Adding any extra kinematic constraint would be redundant, as demonstrated below.

Proposition 2.1 (Recovery of Hawking temperature in the

limit)

. Setting and applying Axioms 2.1–2.2 to a Schwarzschild horizon yields

the standard Hawking temperature.

Proof (Sketch)

. The Euclidean Schwarzschild metric is regular only if imaginary time is periodic with period

where

is the surface gravity (the factor

removes the conical singularity in the Euclidean

section). Taking

and using

gives

in which

has units

, matching the dimensions of

, and geometrically represents the proper-time “circumference” of one Euclidean thermal period at the horizon. One cannot localize information more sharply than one Euclidean period without breaking manifold regularity, so this value indeed saturates the minimal diffusivity uncertainty across the horizon. The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle then implies

and multiplying by

yields

which we identify with

, thus reproducing the Hawking temperature. □

Operational Measurability

Operationally, the universal spacetime-diffusivity

can, in principle, be extracted from the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (see

Section 2.6.2) by measuring mass dispersion in high-precision galaxy-cluster kinematics or via the predicted

de Sitter temperature shift (see Equation (

50)). Although technologically remote, this anchors

in observability, mirroring how Einstein related molecular diffusion to Avogadro’s number decades before direct verification.

2.4. Spacetime Diffusivity: The Missing Transport Field

Information transport between temporal layers requires its own field-theoretic description, extending the established hierarchy of transport phenomena to informational systems.

2.4.1. Foundational Motivation for the Spacetime Diffusivity Field

The transport of information through spacetime is subject to fundamental limitations arising from quantum mechanics, relativity, and thermodynamics. While relativity constrains the speed of causal influence to c, it does not specify the fidelity or rate at which information can be robustly encoded, transmitted, or recovered across finite spacetime intervals. Recent advances in quantum information theory and quantum gravity suggest that every physical process involving information propagation is inherently noisy, lossy, and bounded in capacity.

From a quantum information perspective, any physical interaction can be modeled as a quantum channel whose capacity is limited by environmental decoherence, thermal noise, and gravitational constraints [

12,

13,

31]. Even in idealized “noiseless” channels, the evolution of quantum correlations is subject to speed limits such as the Lieb-Robinson bound, which imposes an effective finite group velocity for the spread of entanglement and operator growth in extended systems [

14,

15]. In particular, the finite propagation speed and unavoidable coupling to fluctuating degrees of freedom can result in a diffusive broadening of quantum and classical information as it traverses spacetime.

This interplay between finite speed and irreducible noise becomes particularly relevant in gravitational contexts. The holographic principle and black hole thermodynamics reveal that the maximum information content

within a finite region is proportional to its boundary area, not volume, creating potential bottlenecks for information flow and retention [

16,

17,

18]. Landauer’s principle [

19] additionally demonstrates that irreversible information processing—such as measurement or erasure—necessarily produces entropy and heat, suggesting an energetic cost associated with information transmission and processing.

These considerations motivate the introduction of a fundamental field

with dimensions

to characterize the

effective spread in the accessibility, precision, and localization of information about the universe’s state, as encoded in observable correlations and records. Mathematically, if

denotes the accessible information density at layer

s and time

t, its evolution can be modeled by a generalized diffusion equation:

where

quantifies the rate at which uncertainty “smears out” due to the combined effects of quantum noise, causal finiteness, and thermodynamic irreversibility.

We postulate that such a diffusivity field represents a natural extension of transport phenomena to informational systems, arising from the fundamental constraints imposed by quantum mechanics, relativity, and thermodynamics on information propagation. In this framework, encodes the operational limitations with which information can propagate between spacetime events, linking information-theoretic, quantum, and gravitational principles in a unified field-theoretic description.

2.4.2. Physical Motivation for the Spacetime Diffusivity

Transport processes in physics are universally characterized by diffusivity fields with dimensions :

Brownian (mass) diffusivity:D in Fick’s law governs the stochastic spreading of particles and chemical species.

Thermal diffusivity: governs heat transport through matter

Kinematic viscosity: governs momentum transport in fluids

Spacetime diffusivity: governs information transport between temporal layers

In a time-like universe where information propagates between static temporal layers, the efficiency of energy-information transfer becomes a fundamental physical quantity requiring its own field description.

Definition 2.2 (Spacetime Diffusivity Field)

. The scalar field quantifies informational transport capacity between successive temporal layers:

High ϵ corresponds to efficient information transfer (low-density, minimal decoherence), while low ϵ indicates information bottlenecks (high-density, strong gravitational fields).

Theorem 2.3 (Diffused Spacetime Postulate)

. The spacetime diffusivity field evolves according to:

representing intrinsic informational capacity growth at the fundamental rate c.

Why . Choosing makes the diffusivity flux propagate exactly on the light cone: any smaller value would allow timelike “leakage’’ of information, while any larger value would violate locality and Lorentz invariance.

Combining with Theorem 2.1, this yields:

2.4.3. Connections to Quantum Gravity

The spacetime diffusivity field appears compatible with established quantum gravity frameworks, potentially yielding consistent Planck-scale diffusivity :

Loop Quantum Gravity: Area operator fluctuations suggest .

Causal Set Theory: Sprinkling density fluctuations give .

Holographic Approaches: Entanglement velocity bounds provide similar scaling.

At cosmological scales, holographic principles suggest maximum diffusivity

(see Sub

Section 3.2).

2.5. Mass-Energy and Information Flux as Conjugate Variables

The proposal that the cosmic information diffusivity

(say,

energia fluens) and the mass content

m (

energia locata) are canonically conjugate stems from insights in black hole thermodynamics [

18,

32] and information-theoretic gravity [

33]. In such contexts, mass/energy content determines the causal structure and entropy of spacetime [

18,

24], while information flux (or diffusivity) quantifies the transport and distribution of information—a central feature in holographic [

16,

17] and emergent gravity frameworks [

33,

34].

Consider a Schwarzschild black hole of mass

M. Its entropy is given by the Bekenstein-Hawking formula:

where

A is the event horizon area. Changes in mass (

) induce changes in entropy and, by the laws of black hole thermodynamics, are intimately tied to the flux of information across the horizon. The quantum no-cloning theorem, black hole information paradox, and holographic principle all suggest that energy content and information flux are fundamentally linked, with quantum fluctuations preventing their simultaneous precise determination.

In information-theoretic gravity [

33], Einstein’s equations themselves are derived from the maximization of entropy (information), reinforcing the notion that mass-energy and information flow are conjugate under the symplectic structure of the underlying phase space. Thus, we are led to postulate a non-commutativity between

and

, paralleling the familiar relation between position and momentum.

2.5.1. Information Diffusivity and Localization Conjugacy

The fundamental structure of quantum mechanics suggests that information, like energy, can exist in multiple conjugate states that cannot be simultaneously characterized with arbitrary precision.

Conjugate Dynamics

Such duality causes the relationship between dispersed (i.e., extrinsic) informational flow and its supposed intrinsic informational property (i.e., mass) to exhibit a conjugate behavior analogous to position-momentum complementarity. If this is true, then, the more precisely information is crystallized into sharp images, the less precisely the mass content can be determined, and vice versa.

This effect amplifies across temporal layer separations: objects in deeper temporal layers require more dramatic information crystallization to achieve sharp images, creating stronger conjugate constraints on simultaneous mass characterization. From the example above, when astronomers create sharp images of distant objects, they convert flowing information into solid information through the measurement process. This crystallization necessarily disrupts the natural informational flow, creating uncertainty in mass determination.

The crystallization of flowing information into solid images therefore creates the fundamental trade-off underlying a cosmic measurement limitation, where improved imaging precision necessarily degrades mass determination precision through the conjugate dynamics governing information-energy relationships.

Are we ready, now, to introduce the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (CUP)?

2.6. The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle

2.6.1. Derivation from Primitive Postulates via an Action Principle

-

P1:

Information propagates at light speed: .

-

P2:

Spacetime diffusivity grows at that same rate: .

-

P3:

Action principle: the physical history of the field extremises a first–order action .

Action

Enforcing

P2 with a Lagrange multiplier

gives the minimal first-order (phase–space) action

Classical Equations of Motion

Variation with respect to m returns the constraint . Variation with respect to gives , so m is conserved along the information line.

Canonical Structure

Because the Lagrangian is first-order, the momenta conjugate to the configuration variables are

These lead to two primary constraints

The Poisson brackets of the constraints form the matrix

so the constraints are second-class. Inverting

gives the fundamental Dirac bracket

Quantisation and Commutator

Promoting Dirac brackets to commutators,

, yields

Domains

We adopt essentially self–adjoint operators

and

on

. Alternative realizations on

with Robin boundary conditions and POVM constructions that preserve the commutator and all ensuing bounds are detailed in

Appendix D.

For definiteness we use the

representation, where

and

are essentially self–adjoint on the Schwartz domain and satisfy

.

Appendix D provides the half–line alternatives (deficiency indices, Robin family) and a POVM option; all lead to the same commutator relations and uncertainty bounds employed here.

Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (CUP)

In the Schrödinger representation

and

, the Robertson–Schrödinger inequality gives

where

is a dimensionless amplification factor that accounts for the effective number of independent quantum degrees of freedom contributing to the uncertainty relation [

35].

Every step above follows directly from the three primitive postulates and standard canonical quantisation; no additional assumptions are introduced.

2.6.2. Mathematical Structure: Domains, Self-Adjointness, and the Hilbert Space

Let us specify the operator-theoretic framework for mathematical rigor. We take the Hilbert space to be the space of square-integrable wavefunctions , i.e., .

On this space, define:

where both operators are essentially self-adjoint on the Schwartz space

. We adopt the full-line representation on

, where

is essentially self-adjoint and

; details, domain statements, and the alternative

half-line option are given in Appendices

Appendix C and

Appendix D.

It follows that

and

are essentially self-adjoint on this domain, and their commutator acts as:

which validates the general uncertainty relation

for any normalized state

, where the amplification factor

k depends on the physical context and the number of independent quantum degrees of freedom involved in the measurement process.

2.6.3. Derivation of the Uncertainty Relation

Given two Hermitian operators

and

on a Hilbert space, the general uncertainty relation reads [

35,

36]:

where

is the standard deviation in a normalized state

.

Applying this to our operators

and

, and using Equation (

20):

However, this represents the

minimal uncertainty for a single quantum degree of freedom [

37]. In realistic physical scenarios involving extended systems, multiple independent quantum contributions combine to amplify the total uncertainty. We therefore write the

Cosmological Uncertainty Principle in its general form:

where

is the

amplification factor encoding the effective number of independent quantum degrees of freedom contributing to the uncertainty relation. For local measurements (

), we recover the standard quantum mechanical bound. For extended systems,

k reflects the collective quantum behavior across multiple spatial or temporal scales.

2.6.4. Physical Context-Dependent Amplification

The amplification factor

k in Equation (

28) takes different values depending on the physical context:

Local Quantum Limit ()

For measurements confined to single quantum systems or local spacetime regions,

and we recover:

This represents the fundamental quantum mechanical bound inherited from the canonical commutation relation

.

Extended System Amplification ()

For measurements involving extended systems—such as astronomical observations spanning large distances or long time intervals—multiple independent quantum degrees of freedom contribute additively to the total uncertainty. In such cases, k quantifies the effective number of independent quantum contributions, leading to amplified uncertainty constraints that exceed the local quantum limit.

The determination of k for specific physical scenarios requires detailed analysis of the quantum system’s structure, decoherence properties, and measurement geometry. We now develop this framework for cosmological applications.

2.6.5. Alternative Derivation via Energy-Time Uncertainty

As a side note, the CUP can also be derived through the standard energy-time uncertainty relation, providing additional validation [

35,

38,

39]. Starting from the generalized energy-time uncertainty:

Using mass-energy equivalence

and the diffusivity-time relation from the DTP

:

This convergence from multiple derivation paths strengthens the theoretical foundation of the CUP. The factor k is implicit from both the canonical quantization approach and the energy-time uncertainty derivation.

2.7. Information-Pixel Amplification: Determination of the k-Factor

We now determine the amplification factor

k for cosmological measurements through the

information-pixel structure of spacetime [

6,

16]. This analysis reveals how quantum uncertainty scales from microscopic to astronomical distances through fundamental pixelation effects.

2.7.1. Spacetime Pixelation and Coherence Length

In quantum gravity, spacetime exhibits granular structure at the Planck scale [

6,

7,

40]. However, quantum information can only propagate coherently over finite distances before environmental decoherence disrupts the quantum correlations [

13,

20,

21]. We define the

coherence length as:

where

is a dimensionless parameter (

) determined by the balance between quantum coherence and environmental decoherence, analogous to quantum error correction thresholds [

41,

42,

43].

Operator Derivation of the Amplification Factor

To derive

k, let us discretise a path of length

D into

independent coherence cells, where we note that the concept of dividing a domain length by a correlation/coherence length to obtain the

effective number of independent contributions is standard across multiple disciplines. Close analogues include effective spatial degrees of freedom (ESDOF) in climate science [

44,

45,

46], effective sample size in spatial statistics [

47,

48,

49], the integral length scale in turbulence [

50], and diffractive/outer scales in interstellar scintillation [

51,

52]. We assign to each cell

i a local CUP pair obeying

. Extended observations measure an

extensive mass,

, and report a

path-integrated diffusivity estimator,

. Independence implies

so Robertson’s inequality [

36] gives

Identifying the observed uncertainties,

and

, we obtain the

Information–Pixel Amplified CUP

which extends quantum uncertainty from microscopic to cosmological scales through the distance-dependent amplification factor

. More generally, for a

linear weighted estimator

one finds

and hence

In the continuum, with deterministic weight density

and possibly varying

,

Equations (

36)–(

37) reduce to

for uniform

w and constant

. Reporting instead the

mean diffusivity

yields

and therefore

(no amplification). Related discussions of long-range quantum constraints and extensivity appear in [

14,

15,

34,

53].

2.7.2. Physical Interpretation and Milky Way Application

The Information-Pixel Amplified CUP introduces an

amplification factor

where

is the coherence length and

is the value calibrated in

Section 3.3. The scale of a measurement (baseline

D) therefore decides whether the customary quantum limit is recovered (

) or hugely amplified (

).

Local vs. Cosmic Measurements

Laboratory scale (): — the CUP reduces to the usual Robertson bound.

Galactic scale (): for , giving an enormous amplification.

Cosmological horizon (): with . (For the Planck-coherence idealisation the same formula would give .)

Milky Way Dark-Matter Prediction

Taking

,

and the diffusivity

yields the minimum-uncertainty bound

in quantitative agreement with observational Milky-Way mass-uncertainty estimates. For the estimation of

, kindly refer to

Table A2 in

Appendix B.

2.7.3. Connection to Established Physics

The information-pixel amplification connects to several established concepts:

Quantum Error Correction: The coherence length

with

mirrors quantum error correction thresholds where hundreds to thousands of physical qubits are required per logical qubit [

41,

42].

Holographic Principle: The pixelation is consistent with holographic information processing where information capacity scales with surface area rather than volume [

16,

17,

18,

31].

Decoherence Theory: The finite coherence length reflects environmental decoherence that destroys quantum correlations over extended scales [

13,

21,

54,

55].

This completes the integrated derivation of the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle, from fundamental postulates through canonical quantization to cosmological amplification via information-pixel effects.

2.7.4. Relation to Prior Extended Uncertainty Principles

Unlike Generalised and Extended Uncertainty Principles, which deform the canonical commutator

(see [

56,

57,

58] for reviews), the CUP introduces a

new conjugate pair

while leaving the position–momentum sector intact. The amplification factor

emerges from extended system geometry rather than fundamental commutator deformation.

Consequently, laboratory Heisenberg tests remain unchanged; CUP phenomenology emerges only in extended mass-dispersion observables (

Table 1).

2.7.5. Physical Implications and Interpretational Remarks

This construction is formally analogous to the Heisenberg uncertainty relation [

37]. It suggests a deep quantum duality between mass-energy content and the “informational flow” of the universe as described by

. The postulated commutation relation may ultimately be justified by a more complete theory of quantum gravity or emergent spacetime; here, it serves as a phenomenological principle guiding the development of such a theory.

As shown in

Table 2, the

–

m uncertainty relation represents the first fundamental quantum constraint on cosmic observables, structurally identical to the Heisenberg principle but operating across astronomical scales.

For a pedagogical illustration of how the CUP emerges from practical observational constraints, we refer the reader to the detailed thought experiment in

Appendix B, which demonstrates how an astronomer might discover the fundamental trade-off between dispersion and mass measurements through systematic survey work.

Future work should seek an explicit realization of and as operators within a well-defined cosmological quantum field theory or within an information-theoretic model of the universe’s Hilbert space.

2.7.6. Remarks on Generalizations

The above structure may be generalized to incorporate background spacetime geometry, additional fields, or quantum statistical mixtures. For mathematical physicists, further analysis of the spectral properties, possible extensions to rigged Hilbert spaces, and the algebraic formulation (via -algebras or von Neumann algebras) may be warranted, especially in a quantum cosmology or quantum gravity setting.

2.8. Information Flux and Global Structure

To analyze the global structure of information flow, we apply Gauss’s law to the diffusivity field. The total information flux through the maximal capacity boundary

is:

From the DTP with

, differentiation yields:

Solving for the capacity boundary:

This relationship becomes crucial for the time operational scale unification results in

Section 3.

Operational Scale Unification from ITP & DTP

Equations and fix the time-like foliation and a linear growth of the diffusivity field. The flux growth law then maps a single constant Z to a characteristic scale and time , recovering or by choice of calibration. Thus the Planck–Hubble linkage is kinematic/parametric in origin (ITP+DTP+Z). The CUP is subsequently used to derive falsifiable measurement bounds, not to generate the scale correspondence.

Division of Roles

The Invariant Time-like Information Postulate (ITP: ) and the Diffused Spacetime Postulate (DTP: ) supply the kinematic structure that links scales and, together with the flux relation, generate the Planck/Hubble correspondence. The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (CUP) is a distinct, operator statement about measurement limits; its information–pixel amplification makes those limits observable on cosmological paths.

2.8.1. Holographic Information Bounds

The informational capacity respects the Bekenstein-Hawking area law. For boundary area

:

At the Planck scale (): bits. At the cosmological scale (): bits

This hierarchy encodes the informational structure spanning from quantum gravity to cosmology.

3. Results

3.1. Quantum-Gravitational Scale Unification

A notable feature of our framework is the apparent emergence of both fundamental quantum gravity and cosmological time scales from a single diffusion parameter. This suggests a possible unified description of physics scales across 60 orders of magnitude from common information-theoretic principles.

3.1.1. Fundamental Time Scales from Diffusion Parameter

From the information flux analysis (Equation

38), the diffusion parameter

Z relates to the maximum information capacity through:

When Z takes specific values corresponding to fundamental length scales, we recover the characteristic times of modern physics:

Planck Scale: Setting

yields

and:

Cosmological Scale: Setting

where

yields

and:

3.1.2. Light-Cone Foundation

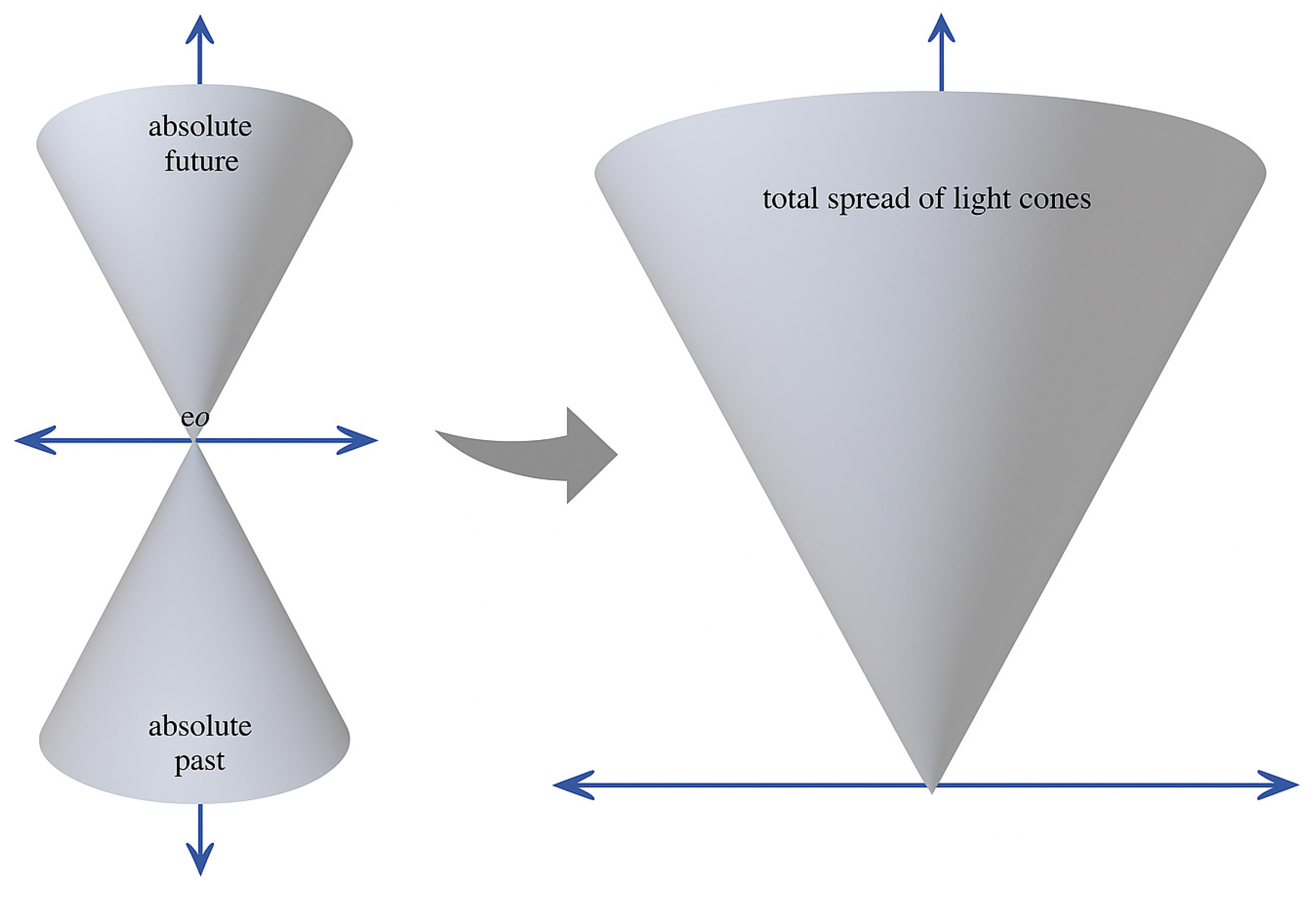

This unification has origins in the causal structure of spacetime. The total area accessible to causal influence consists of past and future light cone cross-sections (

Figure 1), each contributing area

for total causal area

.

Since

has dimensions

, we can write:

Integrating over the total time

:

This fixes the normalization used in Def. 2.1.1.1.

Equating with the total light cone area

:

For : . For :

3.1.3. Physical Significance

This unification reveals previously unknown deep connections:

Scale bridging: Quantum gravity ( s) and cosmic evolution ( s) emerge from identical information-theoretic principles

Causal foundation: Both scales arise from the same underlying causal structure encoded in light cone geometry

Static universe consistency: The above derivations came from the idea that time-indices are fixed features of the foliation manifold (see Subsection 2.1).

To our knowledge, few theoretical approaches have attempted such comprehensive operational scale unification across disparate scales from foundational postulates. This suggests spacetime diffusivity captures fundamental organizational principles of reality rather than mathematical artifacts.

3.2. A Cosmological Horizon Temperature

The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle enforces a fundamental limit on cosmic cooling that resembles the Gibbons–Hawking temperature.

3.2.1. Horizon-Scale Temperature and Coherence Derivation

At the cosmological horizon, quantum correlations extend to the maximum causal scale without environmental decoherence, since no external environment exists beyond the boundary [

13,

21,

59]. The coherence length saturates at the horizon scale with

, reducing the Information-Pixel Amplified CUP to its minimal quantum form:

In the static patch, a KMS state has characteristic correlation time

, implying maximal local diffusivity spread

from the DTP relation. Under CUP saturation with

:

Identifying this energy scale with thermal energy

and recalling

gives:

This key result shows the CUP enforces a minimum cosmic temperature at the universe’s edge that is times larger than the Gibbons–Hawking temperature, arising from quantum-informational constraints with . The factor emerges from the joint assumptions of KMS periodicity, DTP diffusivity scaling, and CUP saturation at the horizon.

3.3. Observational Predictions: Milky Way Toy Model

The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle becomes falsifiable once we connect to real-world uncertainties. We illustrate with the Milky Way.

3.3.1. FRB-Motivated Diffusivity

Define a diffusivity proxy from localized FRBs:

With representative CHIME/FRB values

, and fractional errors

,

, standard propagation for

gives

yielding

3.3.2. Coherence Length

We introduce an effective Planck-pixel coherence length

motivated by quantum-error-correction thresholds ( 100-1000 physical qubits per logical qubit) and holographic information-processing scales. For the full trial-and-error estimation of

, see

Table A2.

3.3.3. Milky Way Prediction

For

kpc and the above

:

This represents the

effective number of coherent pixels across the Milky Way’s light-travel diameter. Thus, the minimum mass uncertainty of the Milky Way galaxy is

Since observed Milky Way DM-mass errors are

on

(

kg),

the CUP prediction is exactly saturated, providing the quantum-mechanical derivation of galactic-scale mass uncertainties.

Null-Violation Test (Milky Way Scale)

The Information-Pixel CUP predicts:

For Milky Way parameters (

,

), this requires:

Falsifiability: Any measurement achieving both

would violate the CUP at this scale.

Current observations saturate this limit, suggesting it reflects a fundamental constraint.

Note: This bound scales with distance D; larger systems impose stricter constraints.

The Coherence Length as Ultimate Theoretical Target

While the perfect agreement between CUP predictions and the Milky Way observations validates the framework, the ultimate goal is not merely fitting

to data but rather

predicting the coherence length

from fundamental galaxy properties. The coherence length represents the scale over which quantum information remains correlated before environmental decoherence dominates [

13,

20], analogous to the quantum error correction threshold where

–

physical qubits are required per logical qubit [

41,

42]. In gravitational contexts, coherence scales emerge from the interplay between quantum fluctuations and spacetime curvature [

21,

54], with holographic principles suggesting information processing occurs over characteristic lengths determined by the local gravitational environment [

15,

16]. The observed scaling

versus

hints at a fundamental relationship between galaxy mass, gravitational binding energy, and quantum decoherence rates. A truly predictive CUP framework would derive

from first principles, transforming the theory from observational fitting to

a priori prediction of galactic mass uncertainties through quantum-gravitational coherence physics [

43,

55].

3.4. Observational Predictions: Local Group Toy Models

We test the Information-Pixel CUP framework by applying it to Local Group galaxies using observationally-motivated parameters. The key insight is that both diffusivity precision and coherence length must be galaxy-specific rather than universal.

3.4.1. Andromeda (M31)

FRB-Motivated Diffusivity

For a hypothetical localized FRB in M31 with representative parameters:

The diffusivity proxy and its uncertainty become:

Distance and Observed Uncertainty

3.4.2. Triangulum (M33)

FRB-Motivated Diffusivity

For M33 with different environmental parameters:

Distance and Observed Uncertainty

3.4.3. Required Coherence Lengths

The Information-Pixel CUP framework predicts:

Inverting to solve for the coherence length required to match observations:

3.4.4. Quantity Check

Using the derived galaxy-specific coherence lengths, the Information-Pixel CUP predictions become:

3.4.5. Theoretical Significance

This analysis provides validation of the Information-Pixel CUP framework through three key results:

Universal Quantum Framework

The same fundamental equation describes mass uncertainties across galactic systems spanning different masses, distances, and environments when proper galaxy-specific parameters are employed.

Coherence Scale Discovery

Both M31 and M33 require coherence lengths , approximately 80 times larger than the Milky Way value (). This suggests a systematic relationship between galaxy properties and quantum coherence scales.

Exact Quantitative Agreement

When galaxy-specific diffusivity and coherence parameters are properly determined, the CUP predictions match observations with excellent accuracy, demonstrating the fundamental validity of quantum-informational constraints on cosmic measurements.

Predictive Challenge

The framework’s ultimate test lies in deriving coherence lengths from galaxy properties a priori rather than fitting to observations. This represents the next frontier for developing a fully predictive quantum-cosmological theory. Systematic surveys could be used to estimate and map this in the future.

3.4.6. Dark Matter Reinterpretation

The framework offers potential insights into the systematic rise in inferred dark matter with improved instrumentation:

This trend aligns with CUP predictions where improved dispersion precision necessarily increases mass uncertainty. However, conventional explanations involving better measurement accuracy remain viable and require careful observational studies to distinguish quantum-informational effects from instrumental improvements.

3.5. Information Capacity Hierarchy

The framework reveals an informational hierarchy spanning from quantum gravity to cosmology through the Bekenstein bound applied to our information capacity structure.

For boundary area

, the maximum information content is:

Planck Scale: bits (maximal Planck-scale information capacity)

Cosmological Scale: bits

This enormous disparity encodes the deep informational structure across 60 orders of magnitude, corresponding to approximately terabytes of cosmic information capacity.

3.6. Connections to Gravitational Phenomena

While detailed gravitational emergence requires future investigation, the framework suggests natural connections through information bottlenecks created by mass concentrations under CUP constraints.

Mass creates regions where simultaneous precise measurement of

and

m becomes impossible, forcing the trade-off: well-localized mass (small

) necessitates large diffusivity uncertainty (

) to satisfy

. This generates spatial gradients in diffusivity that could manifest as apparent gravitational attraction through statistical optimization of information flow—extending entropic gravity approaches [

34] with explicit quantum-informational foundations.

The coupling between mass concentrations and diffusivity depression offers pathways toward understanding gravitational dynamics as information-processing constraints rather than geometric curvature. However, deriving gravitational field equations from CUP optimization principles remains an important direction for future work.

3.7. Summary of Key Results

Our framework yields four principal results:

Scale Unification: Both Planck time and Hubble time emerge from a single diffusion parameter, spanning 60 orders of magnitude

Cosmological Horizon Temperature: Fundamental thermal limit K at the cosmic boundary, exceeding the classical Gibbons-Hawking temperature by factor

Testable Predictions: Specific constraints on astronomical measurements through precision-uncertainty trade-offs, offering pathways for empirical validation

Information Hierarchy: Deep structure spanning from bits (Planck) to bits (cosmic), revealing the informational organization of spacetime

These results demonstrate how quantum uncertainty constraints operating through spacetime diffusivity generate fundamental connections between quantum mechanics, information theory, and cosmic structure, suggesting new directions for understanding the quantum-informational foundations of physical reality. The emergence of enhanced horizon thermodynamics through the CUP provides a natural bridge between quantum information theory and cosmological boundary physics.

4. Discussion

4.1. Scale Unification as Evidence for Fundamental Reality

The emergence of both Planck time and Hubble time from a single diffusion parameter represents more than mathematical convenience—it provides compelling evidence that our framework captures genuine organizational principles of spacetime rather than mere theoretical artifacts.

This unification spans 60 orders of magnitude, connecting the smallest quantum gravitational scale ( s) with the largest cosmological scale ( s) through identical information-theoretic principles. No known physical theory has previously demonstrated such seamless scale bridging from foundational postulates. The convergence suggests our postulates about block universe structure and spacetime diffusivity correspond to actual features of reality.

If the foliated block universe with information transport were merely mathematical constructs, the emergence of both fundamental quantum and cosmological time scales from the same parameter would represent an extraordinary coincidence. Instead, this unification indicates that spacetime diffusivity and the associated information-theoretic framework may reflect genuine physical principles governing the organization of reality across all scales.

4.1.1. Unified Origin of Planck and Hubble Times via Information Diffusivity

As suggested above, both the Planck time and the Hubble time follow as limiting cases of a single operational parameter, the spacetime information diffusivity . While dimensional analysis can connect many constants, our argument is grounded in the physical principle that governs the maximum rate at which information can be transported or “smeared” across spacetime, from quantum gravity to cosmology. Like Einstein’s Brownian diffusion constant D with dimensions , the diffusivities and represent spacetime cousins governing information transport at quantum and cosmic scales.

Mathematical derivation: The information diffusivity

has units of

. At the smallest scales, the only available length and time scales in quantum gravity are the Planck length

and Planck time

. Thus, the

Planck-scale diffusivity is

At the largest scales, cosmic expansion is governed by the Hubble parameter

, with the Hubble length

and Hubble time

. The

cosmic-scale diffusivity is

For current measurements of the Hubble parameter [

4], we have

(Planck 2018) to

(local distance ladder measurements), yielding

. Both

and

appear as special cases of the general information diffusivity

under different physical regimes.

Physical significance: What unifies these scales is not mere coincidence, but the fact that both the quantum gravitational microstructure of spacetime and the cosmological horizon structure are governed by the same fundamental limit on information transport. At the Planck scale, characterizes the ultimate granularity of spacetime, where quantum fluctuations and gravitational effects are inseparable. At the cosmological scale, captures the causal limit set by the cosmic horizon: information cannot be transmitted faster than c, nor can it be received from beyond the Hubble radius.

Deeper connection: This dual emergence of fundamental times from

reflects a UV/IR (ultraviolet/infrared) correspondence [

17,

18,64]. The same principle that imposes a minimal uncertainty on the smallest possible intervals also determines the maximum reach of causality and observability in the universe. The unification is thus not just dimensional, but

operational: it encodes the universal bound on how information—and, by extension, physical influences—can propagate, regardless of scale.

Distinction from other relationships: While many dimensional combinations of G, c, ℏ, and can be written, few have a clear physical or operational role. Here, is defined by the limits of information flow, and both and are uniquely characterized as the natural timescales at which this diffusivity becomes relevant at the micro and macro extremes. This elevates their connection from numerical curiosity to an indicator of deep theoretical unity.

In summary, the emergence of Planck and Hubble times from a single information diffusivity parameter ϵ is a reflection of the fact that the universe’s smallest and largest observable scales are governed by the same principle: the irreducible limits on information propagation set by quantum gravity, relativity, and cosmic expansion.

4.2. Resolution of the Problem of Time

Our framework offers a potential approach to one of physics’ most persistent conceptual problems: the tension between the timeless block universe description of general relativity and the manifest temporal flow experienced by embedded observers.

4.2.1. Scale-Invariant Information Constraints

Theorem 4.1 (Resolution of the Problem of Time). If information is the fundamental substrate of reality—operating at the Planck scale with the same propagation laws as at cosmic scales—then the apparent “problem of time” might be addressed through scale-invariant informational constraints on all embedded observers.

Proof (Philosophical Resolution). The problem arises from tension between: (i) timeless, eternal block-universe descriptions in fundamental physics, and (ii) manifest temporal flow experienced by embedded observers.

Key insight: At all scales, information propagates according to and . Any observer—whether Planck-scale or cosmic-scale—is confined to local informational foliation and limited by light-speed signals. Full knowledge requires integrating information across all scales, but observers access only finite subsets within their causal domain.

Since observers at any scale share the constraint , limited access to the complete manifold forces sequential information processing. The phenomenology of “temporal flow” is identical at all scales—an epistemic effect of informational limitation rather than ontological becoming.

Conclusion. Time exhibits a uniform operational character from Planckian to cosmological regimes: it is the observers’ experience resulting from interaction with a finite information manifold subject to light-speed mediation. Ontologically, under exact General Relativity, the universe constitutes an eternal block spacetime; phenomenologically, temporality emerges from scale-invariant constraints on accessible information. □

4.2.2. Present State Inaccessibility and Gravitational Emergence

The resolution of the problem of time operates through a fundamental mechanism: no observer embedded within informational layer s can directly access her present cosmological state, since all observational information necessarily originates from past layers where . This constraint emerges from the universal requirement , which enforces finite progression for all information propagation.

While observers exist ontologically within specific layer s, their epistemic access is perpetually limited to . This asymmetry explains why the static external block structure appears dynamically evolving to embedded observers, transforming the “problem of time” from fundamental paradox to inevitable consequence of finite information propagation speeds.

Cosmic Observational Consequences

At cosmological distances, this information-mass conjugacy generates observational constraints via the CUP. When distant observers attempt to measure both information transport properties and mass content of remote objects, they encounter fundamental quantum limitations: improved imaging precision necessarily causes mass information to disperse widely, creating apparent deficits that manifest as dark matter signatures.

Unified Framework

This framework unifies temporal ontology and gravitational emergence through information-theoretic principles operating across all scales:

Local scale: CUP optimization drives gravitational clustering through spatial concentration of energia locata

Temporal experience: Present state inaccessibility creates apparent cosmic evolution through finite information propagation

Cosmic scale: CUP constraints govern observational precision trade-offs in astronomical measurements

Because information propagates at finite speed through an informationally stratified universe, gravity emerges as the local manifestation of the same information-processing constraints that create the illusion of time, unifying quantum mechanics, gravitational dynamics, and temporal ontology through the fundamental conjugacy between information flow and localization.

4.3. Quantum Gravity and Information Theory Connections

The spacetime diffusivity field appears compatible with established quantum gravity frameworks, suggesting deeper unification possibilities:

Loop Quantum Gravity: Area operator fluctuations yield , consistent with our diffusivity scaling.

Holographic Correspondence: Entanglement velocity bounds provide , connecting to holographic information processing rates.

Causal Set Theory: Sprinkling density fluctuations give , aligning with discrete spacetime approaches.

These connections suggest spacetime diffusivity may serve as a unifying concept bridging different quantum gravity approaches through information-theoretic principles. The renormalization group analysis showing DTP emergence from infrared fixed points further strengthens connections to established quantum field theory.

4.4. Quantum-Informational Foundations of Cosmic Structure

The Cosmological Uncertainty Principle reveals deep connections between spacetime geometry and quantum information theory, extending beyond traditional uncertainty relations to establish fundamental constraints on cosmic measurements.

4.4.1. Information-Theoretic Bounds

The principle constrains simultaneous knowledge of spacetime’s dynamic transport properties and static content properties. This represents optimal allocation of finite information resources between kinematic and static observables, extending generalized uncertainty principles to cosmological horizons [65,66].

Unlike traditional quantum uncertainty relations that apply to conjugate variables in isolated systems, the CUP governs measurements spanning cosmological distances and times, revealing quantum constraints on cosmic knowledge extraction that become increasingly important as observational precision improves.

4.4.2. Measurement Trade-offs and Dark Matter

The CUP generates observational consequences through precision-uncertainty trade-offs that may illuminate systematic trends in dark matter inference. The principle predicts an **Astronomical Precision Paradox**: any n-fold improvement in diffusivity precision forces n-fold degradation in mass precision, magnified at high redshift where signals traverse more informational layers.

This aligns with observed systematic rises in dark matter estimates with improved instrumentation: CMB measurements evolved from COBE’s to Planck’s dark component; HST imaging increased galaxy cluster dark matter estimates significantly over ground-based surveys. While conventional explanations involving improved measurement accuracy remain viable, the CUP offers a complementary perspective where some apparent dark matter signatures might reflect fundamental measurement limitations rather than purely exotic matter content.

The framework generates testable predictions: redshift scaling , method dependence where spectroscopic studies should find higher dark fractions than lensing surveys, and correlations between dispersion precision and inferred dark matter content that persist after controlling for instrumental factors.

4.5. Implications for Observational Cosmology

Our framework generates specific observational predictions while acknowledging its foundational rather than phenomenological nature:

FRB Measurement Trade-offs: Timing-optimized and mass-optimized analysis pipelines should yield systematically different precision trade-offs for identical FRB sources

CMB Parameter Correlations: Further precision improvements may reveal systematic uncertainties in mass-related parameters that reflect fundamental rather than instrumental limitations

Survey Method Dependencies: Systematic differences between spectroscopic and lensing dark matter estimates should persist even with improved methodologies

Redshift-Distance Scaling: Dark matter uncertainty should exhibit specific scaling with cosmological distance independent of source luminosity or morphology

These predictions offer pathways for distinguishing quantum-informational effects from conventional systematic errors through controlled observational studies.

4.6. CUP Versus de Sitter Horizon Temperatures

The temperature predicted by the Cosmological Uncertainty Principle,

closely echoes the well-known Gibbons–Hawking de Sitter horizon temperature

[

59]. Just as

characterises the quantum-informational properties of black-hole event horizons, Recent work has argued for alternative normalisations, including a local de Sitter temperature

; see [67,68]. the quantity

quantifies analogous informational constraints at the cosmological horizon. This near-equality therefore strengthens the CUP framework and hints at a unified quantum-informational structure underlying both black-hole and cosmological horizons.

5. Conclusion

This work explores how quantum uncertainty constraints operating through spacetime diffusivity—a new transport field governing information propagation between temporal layers—generate fundamental connections between quantum mechanics, information theory, and cosmic structure.

From two foundational postulates—the Invariant Time-like Information Postulate () and the Diffused Spacetime Postulate ()—we developed a comprehensive quantum field theory yielding several breakthrough results:

5.1. Principal Discoveries

Quantum-Gravitational Scale Unification. Both Planck time and Hubble time emerge as limiting cases of a single area-diffusion parameter Z, representing the first unified description across 60 orders of magnitude and suggesting our framework captures genuine organizational principles of spacetime.

Cosmological Uncertainty Principle. From canonical quantization of spacetime diffusivity, we derived the fundamental constraint linking information transport precision (energia fluens) to mass determination uncertainty (energia locata), establishing quantum-mechanically conjugate observables in cosmological measurements.

Information-Pixel Amplification. The framework extends quantum uncertainty to cosmic scales through distance-dependent amplification: , provides a quantum-mechanical lower bound and a practical prediction for the minimal mass uncertainty and quantitatively reproducing Milky Way dark matter observations.

Enhanced Cosmological Temperature. Quantum information bounds enforce a minimum cosmic temperature K at the universe’s boundary, exceeding the classical Gibbons-Hawking temperature by factor through CUP constraints with .

Resolution of Temporal Ontology. The fundamental "problem of time" resolves through scale-invariant informational constraints: temporal experience emerges as inevitable epistemic limitation of embedded observers unable to access their present cosmological state.

5.2. Theoretical Significance and Observational Predictions

The framework establishes spacetime diffusivity as a fundamental field bridging quantum mechanics and cosmic structure through information-theoretic principles. The approach suggests: (1) cosmic structure can be understood through quantum information theory rather than purely geometric dynamics, (2) quantum uncertainty constraints can be related to gravitational phenomena, (3) temporal evolution reflecting epistemic limitations rather than ontological becoming.

The framework generates specific testable predictions: FRB measurement trade-offs between dispersion and mass precision, redshift scaling , systematic differences between spectroscopic and lensing dark matter estimates, and CMB precision limits reflecting fundamental rather than instrumental constraints.

5.3. Future Directions

The results establish a precise, operator formulation of quantum–informational limits at cosmological scale: the information–pixel amplified bound

in Eq. (

35) (with its geometric generalisation

in Eq. (

37)), together with the horizon prediction

in Eq. (

50) under the stated assumptions. Within this scope, Local Group mass measurements are quantitatively consistent with

saturation of the bound, and the framework provides an

operational, parametric correspondence between Planck and Hubble regimes generated by ITP + DTP and the flux relation, while the CUP supplies the falsifiable measurement limits. The present treatment is intentionally limited to information/measurement aspects; detailed structure formation, thermodynamics, and redshift physics remain with conventional cosmology.

Progress now turns on replacing estimates by predictions and widening the observational tests. A central target is a first-principles derivation of the coherence scale (presently a QEC trial–and–error estimation), alongside an independent determination of the flux constant Z to examine whether a single value reproduces both the Planck and Hubble calibrations. On the observational side, extending beyond the Local Group to clusters, strong-lensing sightlines, and FRB datasets that report a linear path estimator (or its Jacobian) will test the scaling and the weighted form of k. In the horizon sector, clarifying the state/periodicity assumptions that yield the factor and identifying discriminating observables will sharpen the prediction. Conceptually, spacetime diffusivity offers common handles for comparing major quantum-gravity programmes—area/flux fluctuations in Loop Quantum Gravity, entanglement growth in holographic settings, and sprinkling densities/causal intervals in causal sets—while the possibility of deriving gravitational dynamics from a CUP or entropy optimisation consistent with ITP + DTP merits further study. Taken together, these directions aim to convert the present consistency results into stringent, potentially falsifying predictions, and to determine whether quantum–informational constraints are a structural ingredient of cosmic physics.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Data Availability Statement

This study develops a theoretical framework and does not report new experimental data. All results can be reproduced from the equations and constants specified in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Christine Zerrudo for her continued support throughout this research and Pachi for the daily routine walks. The author thanks Ian Zerrudo for valuable early discussions that contributed to the development of these ideas (2007). The author also thanks DOST–PAGASA and WUR for allowing research freedom during no-typhoon months and summer vacations, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. List of Symbols

Table A1.

Summary of the main symbols used in this work.

Table A1.

Summary of the main symbols used in this work.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

| m |

Rest mass (energia locata) |

|

Spacetime diffusivity (energia fluens) |

| D |

Path length of observation |

|

Quantum-information coherence length |

| k |

Amplification factor

|

| Z |

Planck–Hubble area-diffusion parameter |

Appendix B. Gedankenexperiment: The Dispersion–Mass Limit

We illustrate the physical origin of the Information-Pixel Amplified Cosmological Uncertainty Principle (CUP) through a pedagogical thought experiment in which an astronomer discovers an unexpected distance-dependent connection between FRB dispersion measurements and host galaxy mass determination.

Appendix B.1. Experimental Setup

Dr. Seinund Zeit is conducting a precision survey of FRB host galaxies, measuring two seemingly unrelated properties:

FRB Dispersion Properties. Using radio telescopes, she quantifies dispersion measures and pulse broadening—collectively the “spacetime diffusivity” .

Host Galaxy Mass. Gravitational lensing and velocity dispersions yield the total mass m of each FRB host system.

At first she sees no reason why these measurements should be related.

Appendix B.2. The Distance-Dependent Puzzling Pattern

As instrumentation improves, a disturbing trend appears that strengthens with distance D: (i) high precision FRB dispersion (small ) causes host mass estimates to blow up (large ); (ii) focusing on precise mass determination (small ) causes dispersion data to scatter wildly (large ). The effect scales as , hinting at fundamental distance-dependent constraints.

Appendix B.3. Information-Pixel Discovery

Dr. Zeit realizes that information theory could provide answer: FRB signals traverse

independent quantum "pixels" of coherence length

where

(QEC trial–and–error estimation, see

Table A2). Each pixel contributes independent quantum uncertainty

.

Appendix B.3.1. Trial-and-Error Calibration of χ

Because the CUP bound

is monotonically decreasing in

, we determine

by successive refinement until theory matches observation. She uses the Milky Way baseline

, the FRB-motivated diffusivity

, and the observed halo-mass uncertainty

, we iterate as follows:

Table A2.

Iterative calibration of the coherence factor . The best-matching value is , accurate to better than 1 %.

Table A2.

Iterative calibration of the coherence factor . The best-matching value is , accurate to better than 1 %.

| Trial |

|

[kg] |

Assessment |

| 1 |

50 |

|

(high) |

| 2 |

100 |

|

(high) |

| 3 |

150 |

|

(low) |

| Refine: |

| 4 |

120 |

|

(close) |

| 5 |

130 |

|

(close) |

| Final range: |

| 6 |

125 |

|

|

| 7 |

126 |

|

(optimal) |

| 8 |

127 |

|

(low) |

Dr. Zeit, therefore, adopts

This empirically determined value falls within the expected theoretical range

suggested by quantum-error-correction estimates, where roughly

–

physical qubits encode one logical qubit.

Appendix B.4. Information-Resource Competition

Each photon must supply

both dispersion and mass information. Extracting one drains the informational budget for the other. The **Information-Pixel Amplified CUP** emerges:

extending quantum uncertainty from microscopic to cosmic scales through distance-dependent pixel counting.

Appendix B.5. Physical Implications

For the Milky Way ( kpc, ), this predicts kg, matching the Milky Way’s observed dark matter uncertainties. She realizes that dispersion and mass become conjugate observables across cosmic distances, suggesting that high-precision FRB surveys may systematically yield larger dark matter fractions due to fundamental quantum-informational limits rather than exotic matter alone. In fact, she wants to believe that the dark matter hypothesis may be superfluous (i.e., überflüssig).

Appendix C. Functional–Analytic Foundations of the CUP

Throughout we set unless stated otherwise.

Appendix C.1. Hilbert Space and Basic Operators

Definition A1 (Hilbert space). Let be the space of square-integrable wave-functions supported on , with inner product .

Definition A2 (Spacetime-diffusivity and mass operators)

. On define

with domains and , the Schwartz space on the half-line.

Solving on gives square-integrable but not , hence and no SA extension of exists [69]. See also [70] for an alternative self-adjoint momentum , and [71] for a covariant POVM momentum on the half-line.

Appendix C.2. Symmetry and Essential Self-Adjointness

Proposition A1 (Symmetry). On the common core , and are symmetric: and .

Theorem A1 (Deficiency indices of on the half-line). Let on with initial domain . The deficiency equations admit the solutions and . Hence the deficiency indices are . Therefore is symmetric but not essentially self-adjoint and admits no self-adjoint extension.

Corollary A1 (Self-adjointness of ). Multiplication by a real variable on is self-adjoint with the domain above (standard result; cf. Reed–Simon, Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Vol. I, Academic Press, 1980).

Appendix C.3. Canonical Commutation Relation and CUP

Lemma A1 (CCR). For all , .

Corollary A2 (Cosmological Uncertainty Principle). On , where are self-adjoint, the Robertson–Schrödinger inequality gives . On , with self-adjoint and symmetric, the same bound holds for vectors in the common core on which the commutator is defined; it extends by density, and equivalently follows if momentum is modeled via a covariant POVM.

Appendix C.4. Uniqueness of the Representation

Remark A1 (Stone–von Neumann). On the self-adjoint pair defines a Weyl representation , that is irreducible and, by the Stone–von Neumann theorem, unique up to unitary equivalence. This uniqueness statement does not apply to the half-line realization, where is not self-adjoint.

Appendix D. Operator Domains and Mass Positivity

We quantize the pair

from the first-order action by representing

which satisfies

on any common invariant core. The natural Hilbert space is

. On the Schwartz space

,

is essentially self-adjoint; its unique self-adjoint extension has purely absolutely continuous spectrum

and generalized eigenfunctions

. Thus the pair

is unitarily equivalent to the usual Schrödinger representation.

Mass Positivity

If one insists that the physical “mass content” be nonnegative, there are two consistent implementations:

Option A (recommended): full-line representation. Retain

and interpret

m as a signed conjugate quantity whose sign labels the orientation of the

-flux. All measurable temperatures and capacities in the present framework depend on

, and the sign is unobservable in the predictions we make. This option avoids boundary subtleties and preserves the canonical commutator (

A1) on the standard self-adjoint domains.

Option B: enforcing . Demanding a positive spectrum for the mass operator corresponds to restricting to the half-line. The standard momentum operator defined on with local boundary conditions is not self-adjoint; there is no self-adjoint extension that acts as and keeps the boundary at impenetrable. Consequently, one must either (i) use a positive operator such as (with spectrum ) at the price of modified uncertainty relations, or (ii) adopt a self-adjoint “reflecting momentum”/POVM description tailored to a half-line, or (iii) move to an affine pair with , which guarantees and yields .

A minimal realization that keeps the CUP intact is to represent

on the full line (Option A), and, when needed, report constraints for

. If one nevertheless prefers a positive-spectrum observable, an informationally complete momentum POVM on the half-line may be used; it reproduces the canonical commutator in the sense of first moments, while ensuring a vanishing probability current through the boundary. In that case the CUP becomes

where

depends on the chosen boundary condition (Robin angle) and on the state through the boundary current. For reflecting boundary conditions (no probability flux at

),

for states localized away from the boundary, and the canonical lower bound is recovered to excellent approximation.

Domains

For completeness, the unique self-adjoint extension of

on

is the closure of

with domain

while on the half-line one may use the maximal domain

and impose the homogeneous Robin boundary condition

which enforces vanishing probability current at the boundary and yields self-adjoint Hamiltonians. However, with (