1. Background

With the rise in the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors, Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains a major global health issue [

1] despite reductions in morbidity and mortality rates due to advancements in therapeutic approaches. Given the prolonged life expectancy resulting from these advancements, patients have to manage CAD symptoms and complex treatment plans over a long duration, affecting as a result their Health-related Quality of life (HRQOL) [

2]. From a cardiologist’s perspective, the assessment of CAD is predominantly medically oriented: generally focusing on specific signs and symptoms indicating which may significantly underestimate patients’ poor HRQoL [

3], because it is not just limited to symptoms due to CAD. Thus, evaluating HRQoL is crucial in managing CAD because it can help clinical decision-making [

4] since the aim of treatment is not just to extend life, but also to relieve symptoms and maximize the highest achievable level of HRQOL, within the constraints imposed by CAD.

Moreover, research on the effects of CAD has primarily focused on mortality risk, survival rates, and serious complications, as well as symptoms like pain and dyspnea. Whereas, other important aspects encountered by clinicians in their daily practice are understudied, such as the patients’ satisfaction with treatment, their mental state (including emotions and self-assessment), their perception of health status and the impact of the disease on their social life and work efficiency. Thus the importance of focusing on patients’ HRQoL in order to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice [

4].

The aim of our study was to assess the health-related quality of life in Tunisian patients with coronary artery disease and to specify the influencing factors associated with health-related quality of life.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was an observational, descriptive and cross-sectional single-center study that was carried out at the cardiology department of HABIB THAMEUR teaching hospital, Tunis. It included patients over the age of 18 years old, treated for coronary artery disease (acute coronary syndrome or chronic coronary disease) seen in outpatient consultation. We included patients having Complete coronary revascularization (Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)) done at least 12 months prior to the interview. We didn’t include patients with a history of psychiatric or cognitive disorders that may impair an oral interview. Patients with incomplete coronary artery revascularization or serious comorbidities (such as a malignant tumor, terminal kidney-failure, sequelae of stroke, amputation, end-stage heart-failure, severe valvular heart disease …) were excluded.

2.2. Study Protocol

Patients seen in outpatient consultation during the study period and meeting the inclusion criteria were consecutively added to the study. The data from each patient was collected, after obtaining a written consent, through an individual fully-structured interview that contained : The patient's Age, Sociodemographic characteristics and Habits, The patient's medical history, Transthoracic echocardiographic findings, Angiographic findings and revascularization protocole. Therapeutic aspects: Adherence to optimal medical treatment, smoking cessation, compliance to treatment and physical activity. Finally The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) : This quality of life questionnaire was translated into Tunisian dialect and adapted to the Tunisian population. It consists of 36 items, each one scored from 0 to 100 (with 100 representing the highest level of functioning possible), that determine the following eight multi-item dimensions of health: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems (RP), bodily pain (BP) , general health(GH) , vitality( VT), social functioning (SF), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) and mental health (MH).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows (version 25.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). We conducted a descriptive study followed by an analytical study. For qualitative variables, we calculated absolute frequencies and percentages. For quantitative variables, we computed means, medians, standard deviations, and determined the extreme values. Concerning Analytic study, Continuous variables were compared using independent samples t test. The correlation between continuous variables was tested using Pearson correlation test. Differences between proportions were evaluated by Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test. In multi-variate analyses, we applied a linear regression analysis to identify which of the following factors remains associated to MCS, PCS and SF-36 after adjusting for confounding variable. A p-value < 0.05 based on two-sided calculation was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Of the 183 patients with a history of coronary artery disease eligible for this study were seen in outpatient consultation from July to December 2023, 33 patients were excluded, as a result 150 patients eligible for the study were included.

The mean age of study population was 62.7 ± 12.8 years and ranging from 38 to 76 years with a male predominance. It is constituted by a group of 118 men (78.7%) and group of 32 women (21.3%) corresponding to a sex ratio of 3.69 The age group of 60-70 years has the largest proportion of participants.

The sociodemographic data, comorbid conditions, clinical characteristics, echocardiographic findings, revascularization data and therapeutic aspects of this study are presented in

Table 1:

3.1. The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)

We studied our population’s participants according to their mental (MCS)(including VT, SF, RE, and MH) , physical (PCS)(including PF,RP,BP and GH) and total (SF36) scores. For the physical component, we observed the highest scores in the dimension Bodily pain (76.3) followed by Physical Functioning (71.1). The scores ranged from 5 to 100.

For the mental component, the items Social functioning and Mental Health demonstrated the highest means (65.4 and 57.4). The scores ranged from 5 to 100.

Table 2.

SF-36 Questionnaire scores.

Table 2.

SF-36 Questionnaire scores.

| |

PF |

RP |

RE |

VT |

MH |

SF |

BP |

GH |

PCS |

MCS |

SF36 |

| Means |

71,1 |

42,2 |

37,6 |

53,6 |

57,4 |

65,4 |

76,3 |

55,9 |

61,4 |

53,5 |

64,3 |

| Standard Deviation |

24,6 |

48,4 |

47,5 |

20,0 |

22,7 |

26,3 |

20,9 |

24,0 |

25,5 |

24,9 |

21,7 |

| Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

16 |

13 |

23 |

0 |

14 |

14 |

20 |

| Maximum |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

96 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

99 |

97 |

| Percentage of patients having an altered score (%) |

20 |

57.3 |

62.7 |

41.3 |

44 |

22.7 |

10.7 |

35.3 |

40.7 |

47.3 |

29.3 |

3.2. Analytic Study

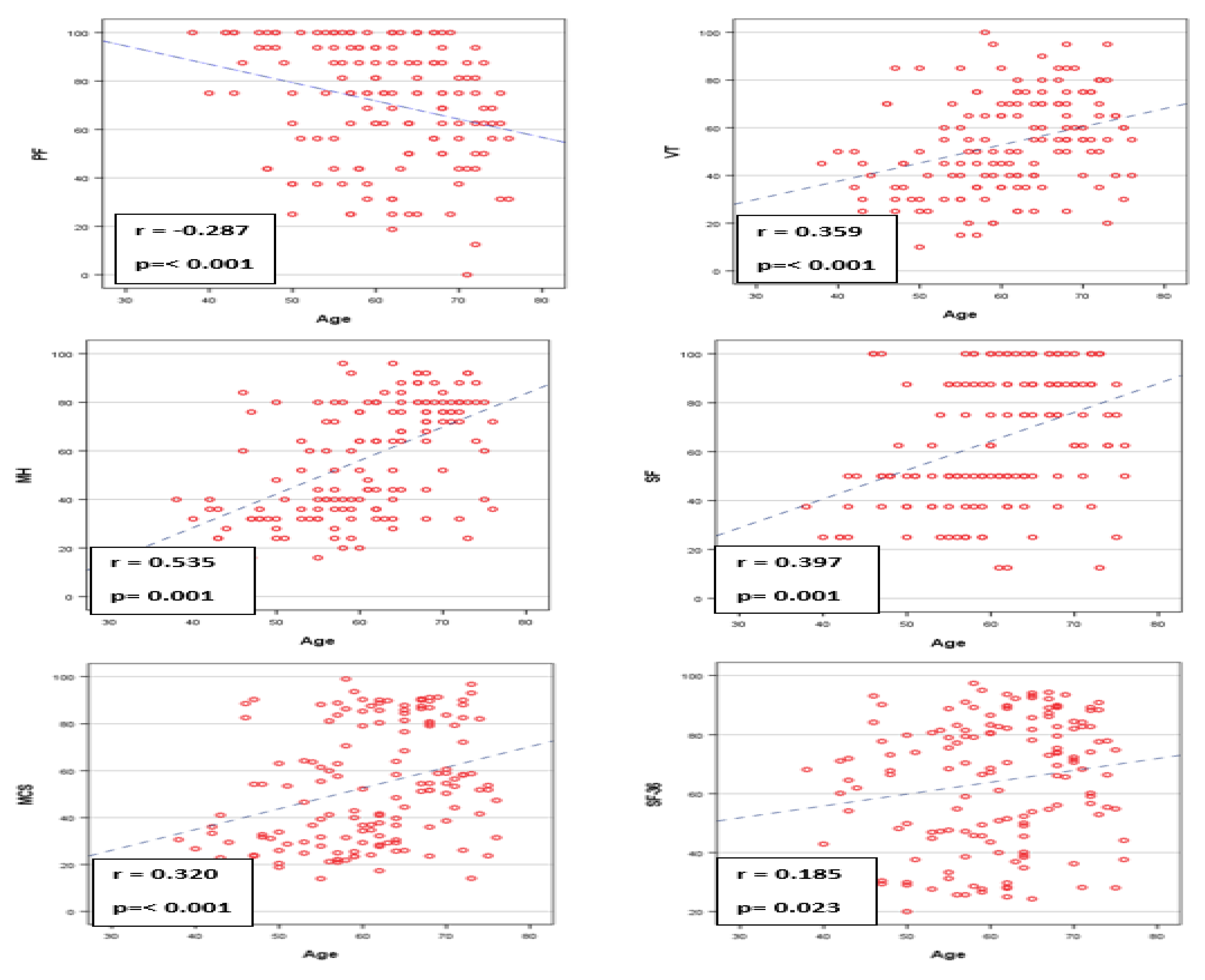

Correlations between patient’s age and the other demographic characteristics are reported in the

Figure 1 and

Table 1

Patients age was inversely correlated with physical functioning (r=-0.28; p<0.001), and positively correlated with vitality (r=0.535; p=0.001), mental health (r=0.535; p=0.001) social functioning (r=0.397; p=0.001), MCS ( r=0.320; p<0.001) and SF 36 ( r=0.185; p=0.023).

Table 3.

Association between demographic characteristics and different SF-36 components.

Table 3.

Association between demographic characteristics and different SF-36 components.

| |

Gender

|

Education level

|

Occupation

|

Social insurance coverage |

Living environment

|

Marital status

|

| |

Men |

women |

p |

Illiterate |

instructed |

P |

Employed |

Retried |

Jobless |

p |

uncovered |

covered |

p |

Rural |

urban |

P |

Married |

Single |

P |

| PF |

74,2 |

59,8 |

0.003

|

62,9 |

75,2 |

0,007 |

74,3 |

72,0 |

60,0 |

0,030 |

69,3 |

71,9 |

0,555 |

66,9 |

72,3 |

0,265 |

71,9 |

68,2 |

0,439 |

| RP |

48,3 |

19,5 |

0.001

|

37,0 |

44,7 |

0,357 |

47,0 |

50,0 |

15,7 |

0,006 |

39,1 |

43,5 |

0,611 |

42,4 |

42,1 |

0,973 |

41,2 |

45,6 |

0,641 |

| EL |

42,1 |

20,8 |

0.014 |

37,3 |

37,7 |

0,968 |

38,9 |

48,7 |

17,3 |

0,027 |

37,7 |

37,5 |

0,983 |

41,4 |

36,5 |

0,599 |

36,8 |

40,2 |

0,714 |

| VT |

55,9 |

44,8 |

<0.001 |

53,8 |

53,5 |

0,920 |

50,4 |

64,2 |

48,1 |

<0,001 |

52,1 |

54,2 |

0,543 |

52,0 |

54,0 |

0,605 |

53,8 |

52,6 |

0,762 |

| MH |

59,2 |

50,8 |

0.063 |

63,3 |

54,4 |

0,023 |

51.5 |

70,6 |

56,6 |

<0,001 |

56,5 |

57,7 |

0,765 |

61,1 |

56,3 |

0,287 |

57,1 |

58,4 |

0,773 |

| SF |

68,5 |

53,9 |

0.005 |

68,8 |

63,8 |

0,274 |

62,9 |

77,2 |

56,0 |

0,002 |

63,6 |

66,2 |

0,572 |

68,6 |

64,5 |

0,438 |

64,2 |

69,5 |

0,306 |

| BP |

79,7 |

63,8 |

<0001 |

69,8 |

79,6 |

0,006 |

77,1 |

82,7 |

64,7 |

0,002 |

72,9 |

77,9 |

0,209 |

72,4 |

77,4 |

0,225 |

76,4 |

76,0 |

0,924 |

| GH |

58,2 |

47,5 |

0.025 |

52,7 |

57,5 |

0,249 |

54,8 |

62,2 |

50,2 |

0,112 |

53,0 |

57,2 |

0,334 |

54,1 |

56,4 |

0,625 |

55,4 |

57,5 |

0,660 |

| PCS |

65,1 |

47,6 |

<0.001 |

55,6 |

64,3 |

0,049 |

63,3 |

66,7 |

47,7 |

0,006 |

58,6 |

62,6 |

0,375 |

58,9 |

62,1 |

0,538 |

61,2 |

61,8 |

0,906 |

| MCS |

56,4 |

42,6 |

0.001 |

55,8 |

52,3 |

0,423 |

50,9 |

65,2 |

44,5 |

0,001 |

52,5 |

53,9 |

0,742 |

55,8 |

52,8 |

0,553 |

53,0 |

55,2 |

0,654 |

| SF-36 |

67,0 |

54,2 |

0.001 |

62,2 |

65,3 |

0,413 |

62,6 |

72,9 |

57,1 |

0,007 |

62,1 |

65,2 |

0,420 |

63,9 |

64,4 |

0,918 |

63,3 |

67,5 |

0,262 |

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

We applied a linear regression analysis to identify which of the factors significantly associated to PCS in univariate analysis, remains associated to PCS after adjusting for the other variable, Results show that only obesity and hospitalization for acute heart failure remain associated to PCS while adjusting to other factors (as shown in

Table 4).

In the other hand, multivariate analysis show that only age, obesity, hospitalization for acute heart failure and the occurance of the last cardiac event in the previous 5 years remain significantly associated to MCS after adjusting for the other variable. (

Table 5)

Concerning SF36, multivariate analysis show that only age, obesity and hospitalization for acute heart failure remain significantly associated to SF-36 after adjusting for the other variable.

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis for Physical Component Scale.

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis for Physical Component Scale.

|

Coefficients |

standard Error |

95% CI |

P |

| Gender |

-10,3 |

6,31 |

0,10 |

2,13 |

0,103 |

| Occupation |

-0,50 |

2,78 |

0,86 |

5,00 |

0,856 |

| Diabetes |

-1,29 |

3,85 |

0,74 |

6,33 |

0,738 |

| Arterial Hypertension |

-5,00 |

3,94 |

0,21 |

2,79 |

0,206 |

| Smoking |

0,20 |

4,66 |

0,97 |

9,42 |

0,967 |

| Chronic renal failure |

-0,078 |

4,16 |

0,98 |

8,15 |

0,985 |

| Obesity |

-26,0 |

3,47 |

0,00 |

-19,2 |

<0,001 |

| Number of hospitalizations |

-7,04 |

4,13 |

0,09 |

1,13 |

0,091 |

| Hospitalisation for acute heart failure |

-10,0 |

4,49 |

0,03 |

-1,15 |

0,027 |

| Number of stents |

1,06 |

2,83 |

0,71 |

6,66 |

0,707 |

| LVEF |

6,15 |

3,29 |

0,06 |

0,37 |

0,064 |

| Physical activity |

-0,90 |

3,96 |

0,82 |

6,93 |

0,821 |

| Optimal medical treatment |

-2,13 |

4,55 |

0,64 |

6,85 |

0,639 |

| Therapeutic compliance |

0,414 |

4,80 |

0,93 |

9,90 |

0,931 |

Table 6.

Linear regression analysis for Mental Component Scale.

Table 6.

Linear regression analysis for Mental Component Scale.

| |

Coefficient |

standard Error |

95% CI |

P |

| Age |

0,92 |

0,23 |

0,47 |

1,37 |

<0,001 |

| Gender |

-5,79 |

6,77 |

19,18 |

7,60 |

0,394 |

| Occupation |

-2,20 |

3,29 |

-8,71 |

4,32 |

0,507 |

| Smoking |

0,86 |

4,56 |

-8,16 |

9,89 |

0,851 |

| Obesity |

-24,0 |

3,33 |

-30,5 |

17,42 |

<0,001 |

| Number of hospitalizations |

3,79 |

3,30 |

-2,73 |

10,32 |

0,252 |

| Hospitalization for acute heart failure |

-9,63 |

4,45 |

-18,4 |

-0,82 |

0,032 |

| LVEF |

-3,75 |

3,06 |

-9,81 |

2,30 |

0,223 |

| Cardiac event occurance in the previous 5 years |

4.49 |

2.19 |

0.16 |

8.83 |

0.042 |

Table 7.

Linear regression analysis for SF-3.

Table 7.

Linear regression analysis for SF-3.

| |

Coefficients |

standard Error |

95% CI |

P |

| Occupation |

-1,05 |

2,04 |

5,09 |

2,98 |

0,608 |

| Diabetes |

-1,63 |

2,84 |

7,24 |

3,98 |

0,568 |

| Smoking |

4,92 |

3,11 |

1,22 |

11,1 |

0,116 |

| Obesity |

-25,3 |

2,74 |

30,8 |

19,9 |

<0,001 |

| Number of hospitalizations |

-3,53 |

3,27 |

10,0 |

2,93 |

0,282 |

| Hospitalization for acute heart failure |

-9,38 |

3,57 |

16,4 |

2,31 |

0,010 |

| Number of stents |

-0,02 |

2,26 |

4,49 |

4,45 |

0,993 |

| LVEF |

-3,49 |

2,55 |

8,53 |

1,56 |

0,174 |

| Optimal medical treatment |

-1,02 |

3,64 |

8,22 |

6,18 |

0,780 |

| Therapeutic compliance |

-1,37 |

3,52 |

8,34 |

5,59 |

0,697 |

| Age |

0,48 |

0,17 |

0,15 |

0,81 |

0,005 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Associated with the Deterioration of Health-Related Quality of Life

1) Gender :

Our population had a male predominance (78.7%). This distribution is very similar to several quality of life studies conducted with coronary artery disease patients in Europe [

5], Asia [

6], Canada[

7] and the United States of America [

8]. Our study highlighted a statistically significant decrease in quality of life scores (MCS, PCS and SF36) among women. This aligns with the findings of several studies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In fact, Regidor et al, [

12] stated that the added stress due to responsabitlities endured by women such as domestic chores , the multiple demands and conflicts derived from their role as mothers and the effort required to compete in an occupational sector dominated by men, explain this worsened HRQoL compared to men.

.

Furthermore, Norris CM et al, demonstrated that the depressive symptoms presented by female CAD patients are strongly associated with poorer recovery from cardiac events.[

10]

2) Age :

The average age of our population was 62.7 ± 12.8 years, with a majority of 39.3% of patients being in the age group between 60 and 70 years, thus classifying it as somewhat elderly and aligning with the average age reported in several studies[

5,

6]. Indeed, the incidence of cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease tends to increase among older patients, given the fact that age itself is an established cardiovascular risk factor[

13].

Our study showed that physical functioning declined with age, whereas self-perception of vitality, mental health, social functioning, the mental component score and the total SF36 score increased.

Consistent with our findings, recent studies [

5,

14,

15,

16] found that older age was significantly associated with lower physical HRQoL and better mental HRQoL

: J Am Coll et al,

stated that the higher ratings of vitality and mental health components in older patients is a reflection of a greater tolerance of reduced health status

compared to younger patients [

16]

.

The reduction in physical capacities in older patients has also been detected in several studies [

6,

17] and may be explained by the fact that ageing is a cardiovascular risk factor and older patients have more chronic diseases compared to the younger population and as a result are exposed to more comorbidities which may lead to a worsened health-related quality of life.

3) Level of education

Our study found that patients with lower education levels (illiterate or primary education) faced more bodily pain and had a worsened physical functioning compared to patients with a higher level of education. Falide et al, [

18] and Barbareschi et al, [

19] stated that patients with lower education levels were more likely to poorly comprehend their disease and therapeutic plans which leads to a lack of adherence to treatment and missed medical appointments causing as a result higher levels of stress and anxiety and a diminishing HRQoL. On the contrary, patients with higher levels of education were more likely to have a better understanding of their medical condition, strictly follow their therapeutic regimen and improve their lifestyle and habits and as a consequence have an improved physical status and a better HRQoL.

4) Occupation :

Our patients showed that the lowest scores were detected in jobless patients. This aligns with the findings in worldwide researches, in fact unemployment was among the predictive factors of poor health-related quality of life in multiple studies [

2,

12,

15,

20]. The majority of jobless patients in our study have stated that the cause of their unemployment was either the recurrence of chest pain after getting back to work ,despite a complete revascularization, limiting as a result their capacities to perform well or losing their job during the occurance of the first cardiac event. This highlights the huge negative impact of CAD on the patients’ lives. These same reasons have also been reported in a study conducted by Crilley JG et al, [

21]

Our employed patients in the other hand, perceived their health more positively when they were professionally active, both for their overall and physical scores. This can be explained by the sense of security provided by employment regarding financial resources, which are predictive of good quality of life when they are adequate.

5) Tobacco smoking and comorbidities:

We noted in our study that patients with a history of tobacco smoking, or comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, arterial hypertension and renal failure presented significantly lower scores than non-smokers.

Several studies have shown that CAD patients with a history of tobacco smoking have an inferior HRQoL compared to non-smokers [

2,

6,

22,

23,

24]. This negative effect on HRQoL in general and especially its physical component has been linked to

smoking being a risk factor for decreased muscle strength and as a consequence a decreased physical performance[

25]

. On the other hand, the stress caused by the change in lifestyle, such as smoking cessation, can hinder the mental component of HRQoL.

4.2. Obesity

Obesity can harm HRQoL as it has been shown that obese patients had a higher prevalence of depression and their HRQoL was significantly reduced compared with patients with a normal BMI [

8,

26,

27]. Simultaneously weight loss improved HRQOL outcomes in patients with established CAD [

28]. This can be explained by the fact that obesity can become an obstacle limiting everyday’s physical activities in addition to the self-image complexes it can induce, causing as a result a reduction in both physical and mental components of HRQoL.

4.3. Arterial Hypertension

It is entirely plausible that patients with arterial hypertension report diminished physical health-related quality of life due to the chronicity, severity, and duration of their condition. On the other hand, the long-term use of antihypertensive medications, combined with food restrictions and behavioral adjustments to manage the illness, may cause additional stress on patients, negatively impacting their mental HRQoL. As a result arterial hypertension can affect both physical and mental components of HRQoL[

2,

6,

22,

29]

.

4.4. Diabetes

Diabetic patients in our study presented a significantly lower PCS and SF-36T than those without diabetes, this aligns with the findings of most studies [

2,

4,

8,

11,

29,

30].

Sherman et al[

31] explained that the chronic nature of diabetes and its associated complications, such as peripheral vascular disease, renal failure and diabetic retinopathy can contribute to a decline in the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients with CAD.

4.5. Kidney Failure

Our study showed a lower HRQoL in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). This association between renal failure and the decline in health perception has been confirmed by several studies [61–66]. Frazer et al [64] linked this association to the anemia and its symptoms (dizziness, weakness, shortness of breath), wheras Sharma et al, [62] suggested that CKD places various limitations on patients' daily lives, especially regarding their physical functioning (inability to preform self-care and lack of energy) and mental functioning ( higher rates of anxiety and depression) even in the early stages of the disease, leading to a decline in health-related quality of life.

5) History of coronary artery disease :

4.6. Number of Hospitalizations

Our study showed that the HRQoL of patients is inversely proportional to the number of hospitalizations for cardiac events. This aligns with various studies that proved that recurrent hospitalizations for cardiac events affect poorly the HRQoL of CAD patients [

49,

50,66–70] .

This phenomenon can be explained by the effect of hospital admissions for cardiac events on both the mental and physical health of patients.

Concerning the mental component, every cardiac event and its symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue) cause frustration for patients as they have to go through the same experience repeatedly. In addition, with every new readmission, patients become more anxious in fear of a new heart cardiac event [71] and feel less « hopeful » for a return to their intial premorbid state which can cause depression[72].

Concerning the physical component, the sequel of every new cardiac event (persistent angina or dyspnea, heart failure) represents a new limitation of patients’ physical functioning, this can result in a decrease in the physical component and the overall status of HRQoL of CAD patients.

4.7. Cause of Hospitalization

The patients in our study who have been hospitalized for STEMI or acute heart failure presented lower scores of HRQoL than the rest of our population. This can be explained by the more serious sequels of STEMI as it causes extensive heart damage that requires more aggressive treatment and longer recovery, impacting daily activities and overall well-being in addition to a higher risk of complications.

Moreover, in our multivariate analysis, the hospitalization for acute heart failure was detected as an independent factor of impairment of health-related quality of life in the SF36 total score and both of its physical and mental scales.In fact, several international studies found a deteriorating HRQoL among CAD patients admitted for heart failure [

22,

41] including physical, psychological, and social dimension.

4.8. Coronary Artery Status

Our study showed that an increasing number of diseased coronary vessels negatively impacts multiple subscales of HRQoL (PF, GH, PCS and SF-36). In fact, the number of diseased vessels is a reflection of the coronary artery disease severity, making this parameter the most important determinant of HRQoL of CAD patients. In addition to the necessity of multiple readmissions and revascularization procedures that can poorly affect both mental and physical components of HRQoL.

4.9. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

We found that a mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction impaired most components of the SF-36 (PCS, MCS, PF, PL, EL, VT, MH, BP and GH). All these scores were lower in patients with an LVEF <40%. These findings are consistent with various studies [

39,

42,

43]

.

Wilson et al [

42] suggested that patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction experience symptoms like fatigue, dyspnea, and sleep disturbances more than patients without a myocardial systolic dysfunction. These symptoms, the added treatment of myocardial dysfunction, the lifestyle changes and the reccurent admissions for acute heart failure can subsequently impact the patients' functional status, overall health, and health-related quality of life.

4.10. Therapeutic Aspect

4.10.1. Physical Activity

Our study showed that there is a significant positive association between physical activity and HRQoL. We found that patients who exercise regularly presented higher Physical component and SF-36 scores.

Most studies indicate the importance of following medical recommendations for lifestyle changes, especially physical activity as it

prevents the progression of the disease, positively influencing the quality and length of life. [

44,

45]

K. Kontoangelos et al’s, research on risk factors affecting the quality of life, which included evaluating subjects' physical capacity through a treadmill test, revealed that both the intensity and duration of exercise were linked to improved HRQoL scores among patients[

46].

Akyuz et al, attributed this improvement to the fact that physical activity lowers cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, reduces rehospitalization, alleviates psychological stress, and helps manage risk factors for coronary artery disease, including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity[

46].

4.10.2. Smoking Cessation

We didn’t detect any association between smoking cessation and PCS, MCS and SF-36.

Nevertheless, multiple studies found a negative influence of smoking on overall HRQoL in CAD patients after revascularization [

47,

48]. Persisting smoking limits vascular reconstruction and the maintenance of coronary blood flow by causing microvascular endothelial dysfunction, which can lead to persistent angina [

49]. Additionally, their study found that smoking reduces individuals' capacity to exercise following angioplasty.

Xue et al, compared the HRQoL of non-smokers, smokers and quitters and found that quitters had a similar HRQoL to non-smokers and both groups had significantly greater improvements in HRQoL. The multivariate analysis showed that persistent smoking was an independent risk factor for worsened HRQoL.

4.10.3. Medical Treatment and Therapeutic Compliance

Our study found that adherence to optimal medical treatment was attained in the majority of participants (73.3%). Moreover, the adherent patients to optimal treatment presented higher PCS and SF-36 scores.

These findings are in agreement with numerous studies [

50,

51,

52,

53] In fact, a report of the American College of Cardiology in collaboration with the American Heart Association Task Force [

54] stated that improving adherence to medication is crucial for CAD management, as the continuous therapy is linked to improved clinical outcomes, which positively influence health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

An explanation provided for the positive effect of medication adherence, is the consideration of long-term effects of treatment on heart remodeling and the maintenance of optimal blood flow following revascularization. These factors contribute to better physical health in patients with coronary artery disease, leading to improvements in their physical, mental, and overall HRQoL.

4.11. Strenghts and Limitations

The key strengths of this study lie in the fact that: This study is, to our knowledge, the first Tunisian study to assess health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. The assessment of health-related quality of life was based on the mostly used questionnaire: The SF36 questionnaire Our questionnaire is in Tunisian dialect and is adapted to the Tunisian population [

50]. However, some limitations have to be addressed to the present study :The small population size (150 patients), the mono-centric design and absence of a control group (Patients without coronary artery disease)

5. Conclusions

Coronary artery disease remains a major health issue that places a heavy burden on public health systems as well as on patients both globally and in Tunisia.

The recent therapeutic advancements have certainly contributed in improving prognosis and longevity, but

Unfortunately, Health-related quality of life in Tunisian CAD patients has, to our knowledge, been minimally explored.

Our results indicated that the majority of our population had a good quality of life according to the SF-36 total score and both of its components: physical and mental Component Scale .

Our findings showed a significant association between the following factors: female gender, age, low levels of education, unemployment, dyslipidemia, diabetes, arterial hypertension, renal failure, obesity, smoking, lack of physical activity, recurrent hospitalizations, admissions for acute heart failure or STEMI, multiple vessel disease, recent cardiac events, mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and non-adherence to medical treatment.

Our study thus highlighted the factors that can impair the health-related quality of life of coronary artery disease patients in Tunisia such as age, obesity, comorbidities, and recurrent hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure. These factors, mostly modifiable, should be addressed and managed at each medical contact: during therapeutic education sessions, regular consultations, or hospital stays.

A multidisciplinary approach is essential for a better management. Additionally, we should consider more frequently assessing the mental health of these patients and recommend psychiatric consultations if needed.

Lastly, improving the health-related quality of life should be the ultimate goal of healthcare providers and should be considered a lifelong plan to be discussed with the patients throughout the progression of their illness.

List of Abbreviations

CAD: Coronary artery disease

HRQoL: Health-related Quality of life

PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention

CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting

SF-36: The 36-item Short-Form health survey

PF : Physical functioning

RP : Role limitations due to physical problems

BP : Bodily pain

GH : General health

VT : Vitality

SF : Social functioning

RE : Role limitations due to emotional problems

MH : Mental health

PCS : Physical component scale

MCS : Mental component scale

WHO : World Health Organisation

ACS : Acute coronary syndromes

CCS : Chronic coronary syndrome

ESC : European Society of Cardiology

LVEF : Left ventricular ejection fraction

NSTEMI : Non-sustained ST-Elevation myocardial infarction

STEMI : Sustained ST-Elevation myocardial infarction

HF : Heart failure

CKD: Chronic kidney disease

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gaidai O, Cao Y, Loginov S. Global Cardiovascular Diseases Death Rate Prediction. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101622. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad I, He HG, Kowitlawakul Y, Wang W. Narrative review of health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with coronary heart disease. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016, 22, 4–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, Davies AR, Jette AM, Fink A, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991, 114, 451–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen SS, Martens EJ, Denollet J, Appels A. Poor health-related quality of life is a predictor of early, but not late, cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Psychosomatics. 2007, 48, 331–7. [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz I, Łoboz-Grudzień K. Factors influencing quality of life up to the 36th month follow-up after treatment of acute coronary syndrome by coronary angioplasty. Nurs Res Rev. 2015, 5, 23–31.

- Wang W, Lau Y, Chow A, Thompson DR, He HG. Health-related quality of life and social support among Chinese patients with coronary heart disease in mainland China. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014, 13, 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Norris CM, Ghali WA, Galbraith PD, Graham MM, Jensen LA, Knudtson ML, et al. Women with coronary artery disease report worse health-related quality of life outcomes compared to men. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004, 2, 21. [CrossRef]

- Conradie A, Atherton J, Chowdhury E, Duong M, Schwarz N, Worthley S, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) and the Effect on Outcome in Patients Presenting with Coronary Artery Disease and Treated with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI): Differences Noted by Sex and Age. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5231.

- Kristofferzon ML, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Perceived coping, social support, and quality of life 1 month after myocardial infarction: a comparison between Swedish women and men. Heart Lung J Crit Care. 2005, 34, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Norris CM, Spertus JA, Jensen L, Johnson J, Hegadoren KM, Ghali WA, et al. Sex and gender discrepancies in health-related quality of life outcomes among patients with established coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008, 1, 123–30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreel TH, Nieuwkerk PT, Hartog ID, Netjes JE, Vonk ABA, Lemkes J, et al. Gender differences in quality of life in coronary artery disease patients with comorbidities undergoing coronary revascularization. PLOS ONE. 2020, 15, e0234543.

- Regidor E, Barrio G, de la Fuente L, Domingo A, Rodriguez C, Alonso J. Association between educational level and health related quality of life in Spanish adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999, 53, 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–337.

- Beck CA, Joseph L, Bélisle P, Pilote L. Predictors of quality of life 6 months and 1 year after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2001, 142, 271–9. [CrossRef]

- Hawkes AL, Patrao TA, Ware R, Atherton JJ, Taylor CB, Oldenburg BF. Predictors of physical and mental health-related quality of life outcomes among myocardial infarction patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013, 13, 69.

- Quality of life after coronary angioplasty or continued medical treatment for angina: three-year follow-up in the RITA-2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 35, 907–14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cf M de L, Hm K, V V, Cs W, Ta G, Lf B, et al. A population-based perspective of changes in health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction in older men and women. J Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. juill 1998 [cité 26 août 2024], 51(7). Disponible sur: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9674668/.

- Failde I, Medina P, Ramirez C, Arana R. Construct and criterion validity of the SF-12 health questionnaire in patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010, 16, 569–73.

- Barbareschi G, Sanderman R, Kempen GIJM, Ranchor AV. Socioeconomic Status and the Course of Quality of Life in Older Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Int J Behav Med. 2009, 16, 197–204.

- Johnson JA, Coons SJ. Comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-12 in an adult US sample. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 1998, 7, 155–66.

- Crilley JG, Farrer M. Impact of first myocardial infarction on self-perceived health status. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians. 2001, 94, 13–8.

- Wang W, Thompson DR, Ski CF, Liu M. Health-related quality of life and its associated factors in Chinese myocardial infarction patients. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014, 21, 321–9.

- Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Magid DJ, McCarthy M, Shroyer ALW, MaWhinney S, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004, 77, 1508–13.

- Barta Z, Harrison MJ, Wangrangsimakul T, Shelmerdine J, Teh LS, Pattrick M, et al. Health-related quality of life, smoking and carotid atherosclerosis in white British women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010, 19, 231–8.

- Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Smith LM. Smoking is a risk factor for decreased physical performance in elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007, 62, 93–100.

- Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Sharma AM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Association between obesity and health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Obes 2005. 2010, 34, 1434–41.

- Lidell E, Höfer S, Saner H, Perk J, Hildingh C, Oldridge N. Health-related quality of life in European women following myocardial infarction: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015, 14, 326–33.

- Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation, exercise training, and weight reduction on exercise capacity, coronary risk factors, behavioral characteristics, and quality of life in obese coronary patients. Am J Cardiol. 1997, 79, 397–401.

- Wang W, Lopez V, Ying CS, Thompson DR. The psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the SF-36 health survey in patients with myocardial infarction in mainland China. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2006, 15, 1525–31.

- Uchmanowicz I, Loboz-Grudzien K, Jankowska-Polanska B, Sokalski L. Influence of diabetes on health-related quality of life results in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with coronary angioplasty. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 217–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman AM, Shumaker SA, Kancler C, Zheng B, Reboussin DM, Legault C, et al. Baseline health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease: the Estrogen Replacement and Atherosclerosis (ERA) trial. J Womens Health 2002. 2003, 12, 351–62.

- Darvishpour A, Javadi-Pashaki N, Salari A, Sadeghi T, Taleshan-Nejad M. Factors associated with quality of life in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. Int J Health Sci. 2017, 11, 35–41.

- Salazar A, Dueñas M, Fernandez-Palacin F, Failde I. Factors related to the evolution of Health Related Quality of Life in coronary patients. A longitudinal approach using Weighted Generalized Estimating Equations with missing data. Int J Cardiol. 2016, 223, 940–6.

- Munyombwe T, Hall M, Dondo TB, Alabas OA, Gerard O, West RM, et al. Quality of life trajectories in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a national longitudinal study. Heart Br Card Soc. 2020, 106, 33–9.

- Oldridge N, Gottlieb M, Guyatt G, Jones N, Streiner D, Feeny D. Predictors of health-related quality of life with cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 1998, 18, 95–103.

- Smedt DD, Clays E, Annemans L, Doyle F, Kotseva K, Pająk A, et al. Health related quality of life in coronary patients and its association with their cardiovascular risk profile: Results from the EUROASPIRE III survey. Int J Cardiol. 2013, 168, 898–903.

- Dias CC, Mateus P, Santos L, Mateus C, Sampaio F, Adão L, et al. Acute coronary syndrome and predictors of quality of life. Rev Port Cardiol. 2005, 24, 819–31.

- Failde II, Soto MM. Changes in health related quality of life 3 months after an acute coronary syndrome. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6, 18.

- Lee DTF, Choi KC, Chair SY, Yu DSF, Lau ST. Psychological distress mediates the effects of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics on the physical health component of health-related quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014, 21, 107–16.

- Positive psychology differences and risk stratification between STEMI and NSTEMI [Internet]. [cité 2 oct 2024]. Disponible sur: https://esc365.escardio.org/journal/52969.

- Lewis EF, Li Y, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Weinfurt KP, Velazquez EJ, et al. Impact of cardiovascular events on change in quality of life and utilities in patients after myocardial infarction: a VALIANT study (valsartan in acute myocardial infarction). JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 159–65.

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995, 273, 59–65.

- R E, C C, M R, G de G, D C, C D, et al. Indicators of myocardial dysfunction and quality of life, one year after acute infarction. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. oct 2001 [cité 2 oct 2024], 3(5). Disponible sur: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11595604/.

- O A, A H, V K, M V, K P, A K, et al. Effects of Physical Activity on Aging Processes in Elderly Persons. 2019 [cité 3 oct 2024], Disponible sur: https://reposit.uni-sport.edu.ua/handle/787878787/1824.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association [Internet]. [cité 3 oct 2024]. Disponible sur: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052.

- Kontoangelos K, Soulis D, Soulaidopoulos S, Antoniou CK, Tsiori S, Papageorgiou C, et al. Health Related Quality of Life and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Behav Med Wash DC. 2024, 50, 186–94.

- Dąbek J, Styczkiewicz M, Kamiński K, Kubica A, Kosior DA, Wolfshaut-Wolak R, et al. Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease-Multicenter POLASPIRE II Study. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3630.

- Dibben GO, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2023, 44, 452–69.

- Staniute M, Brozaitiene J, Bunevicius R. Effects of Social Support and Stressful Life Events on Health-Related Quality of Life in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013, 28, 83.

- Lee YM, Kim RB, Lee HJ, Kim K, Shin MH, Park HK, et al. Relationships among medication adherence, lifestyle modification, and health-related quality of life in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018, 16:100.

- Krack G, Holle R, Kirchberger I, Kuch B, Amann U, Seidl H. Determinants of adherence and effects on health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 136.

- Nouamou I, Mourid ME, Ragbaoui Y, Habbal R. [Medication adherence among elderly patients with coronary artery disease: our experience in Morocco]. Pan Afr Med J. 2019, 32, 8.

- Zakeri MA, Tavan A, Nadimi AE, Bazmandegan G, Zakeri M, Sedri N. Relationship Between Health Literacy, Quality of Life, and Treatment Adherence in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. HLRP Health Lit Res Pract. 7, e71-9.

- Jl A, Cd A, Em A, Cr B, Rm C, De C, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol.

- Guermazi M, Allouch C, Yahia M, Huissa TBA, Ghorbel S, Damak J, et al. Translation in Arabic, adaptation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Tunisia. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2012, 55, 388–403.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).