1. Introduction

The two-level inverter, as a power converter, is widely used in new energy generation systems such as photovoltaic, wind power, and micro-grids [

1,

2]. Among control strategies for voltage source inverters, model predictive control (MPC) has been widely studied due to its advantages of control flexibility, reliable operation, and simple complementation [

3]. Related improvement research focuses on reducing computational complexity, decreasing switching frequency, suppressing common-mode voltage, or reducing current harmonics [

4,

5].

However, although existing improvements enhance performance from different perspectives, they fail to fundamentally solve the model mismatch problem. MPC highly relies on model accuracy, but numerous uncertain factors during actual operation can significantly affect model precision, thereby degrading control performance [

6]. Model mismatch directly leads to prediction value deviation; for instance, load inductance parameter mismatch has been proven to increase output current harmonics [

7].

To mitigate parameter sensitivity, researchers have proposed strategies such as online parameter correction [

8,

9] and real-time inductance identification [

10]. However, these methods are either computationally complex [

11] or only focus on specific parameter variations while neglecting other system components [

12]. Model-free predictive control (MFPC) adopts the ultra-local model to replace traditional modeling, aiming to circumvent the impact of mismatch [

13]. Nevertheless, MFPC methods relying on multi-cycle historical data for future state estimation often exhibit some modeling errors [

14], and the substantial computational burden results in sluggish dynamic response [

15,

16].

In order to improve this problem, the observer is introduced to reduce the computational burden [

17]. For example, methods combining sliding mode observer (SMO) have been used to enhance the speed regulation performance of permanent magnet synchronous motor [

18,

19] and improve the dynamic response of two-level inverters [

20,

21]. However, such methods still have limitations: the observer gain parameters are often preset offline, making it difficult to adapt to wide-range external disturbances; the inherent feedback delay of the system always lags behind the rapid changes of disturbances, constraining the dynamic performance [

22].

To further enhance control performance under complex operating conditions, this paper proposes a model-free predictive control strategy based on an adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer (ASTSMO), termed ASTSMO-MFPC. The core contributions lie in: 1) Employing the ultra-local model to replace the traditional discrete model, circumventing model mismatch in MPC at its source; (2) Designing a super-twisting sliding mode observer (STSMO) to accurately estimate the dynamic components of the model; (3) Designing an adaptive algorithm that formulates the observer gains as adaptive gains related to the current observation error, thereby constraining the impact of boundary uncertainty in the dynamic components on the system and significantly enhancing system robustness across diverse operating conditions. Simulation results verify the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method compared to existing schemes. The structure of the paper is as follows: Problem Formulation, Proposed Control Strategy, Simulation Verification and Conclusion.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Mathematical Model and MPC Strategy

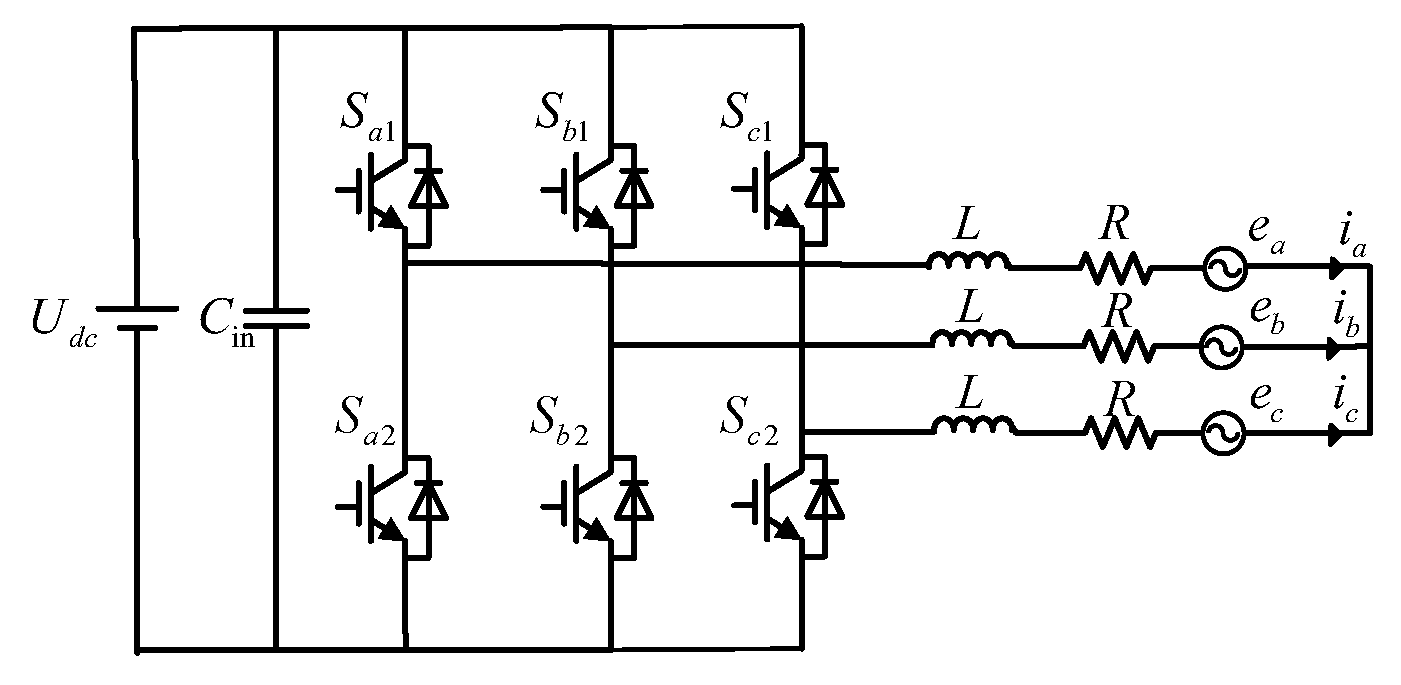

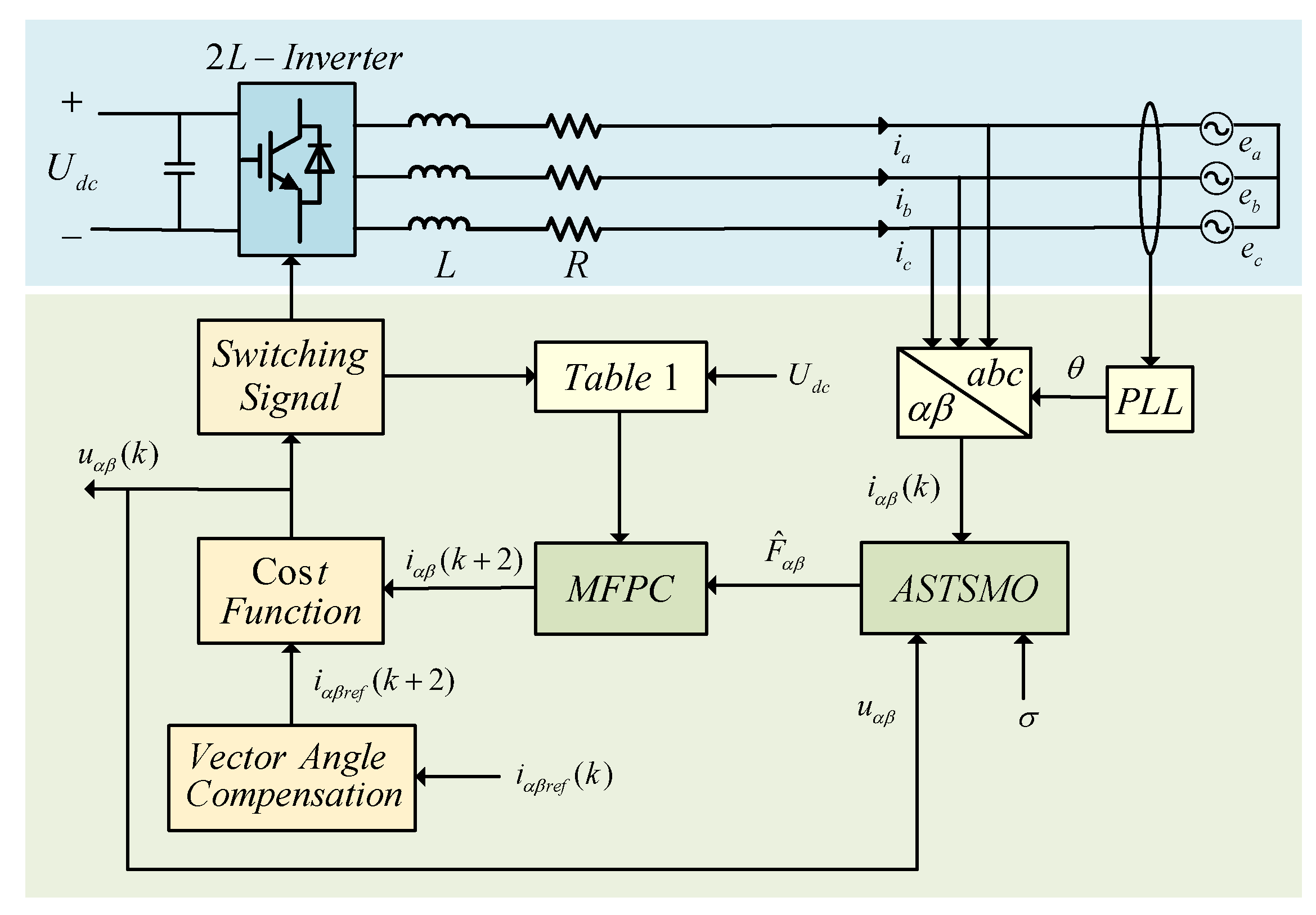

Figure 1 shows the topology of a three-phase two-level inverter. Here,

is the DC voltage;

L and

R are the filter inductance and equivalent parasitic resistance, respectively;

,

,

and

,

,

correspond to the three-phase AC grid voltages and inverter output currents, respectively;

(

) represents the switching states of the power devices. The two switching devices in each phase leg operate in complementary conduction.

indicates that the upper switching device is turned ON, while

indicates that the upper switching device is turned OFF. The valid combinations of these switching states generate eight distinct discrete space voltage vectors, as listed in

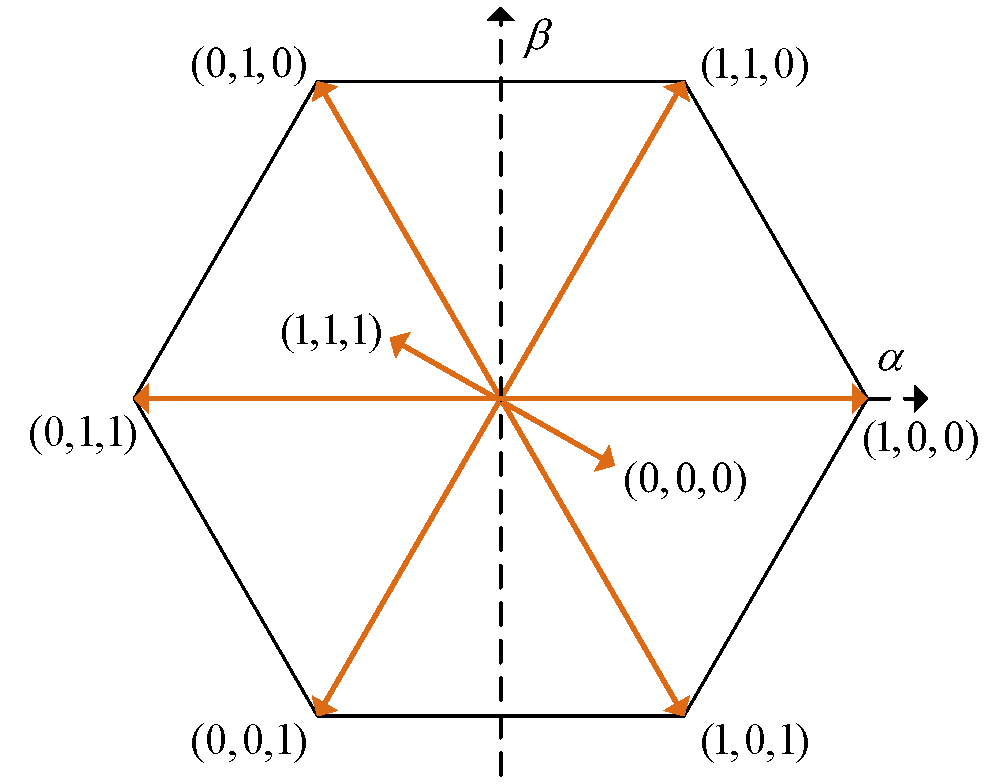

Table 1, with their positions in the space vector diagram shown in

Figure 2.

Ideally, the inverter in the

stationary coordinate system can be modeled as:

where

,

and

are the output voltage of the inverter;

,

and

are the output current of the inverter;

,

and

are the AC voltage.

Assuming that the sampling period is T, the current prediction expression at time

can be obtained by discretizing (

1) as:

where

denotes the value of the variable

x at time

;

represents the value of variable

x at time

.

To compensate for the inherent computational delay in the model predictive control strategy, the following compensation mechanism is adopted: First, the optimal voltage vector

and

obtained in the previous control cycle are substituted into (

2), computing the predicted currents

and

at time

. Subsequently, all candidate voltage vectors

shown in

Figure 2 are sequentially substituted into (

3) to compute their corresponding predicted currents

at time

. This achieves delay compensation based on two-step prediction:

where

denotes the value of the variable

x at

.

When the sampling frequency is significantly higher than the system’s fundamental frequency, it is reasonable to assume that the grid voltage vector remains approximately constant over one sampling period, i.e.,

. The compensation of the reference current is achieved using the vector angle compensation method, expressed as:

where

is the given reference current.

To determine the optimal voltage vector, the cost function defined in (

5) evaluates the current tracking performance for each candidate vector. By minimizing the cost function, the optimal voltage vector is selected and applied to the inverter switching actions in the next control cycle.

As clearly seen from (

3), the predicted current is strongly coupled with the inductance parameters

L and resistance parameters

R. When external factors cause the actual parameters of the device to deviate from the modeled parameters (a phenomenon termed parameter mismatch), significant errors arise. The following section will derive detailed expressions to quantify this error.

2.2. The Effect of Parameter Mismatch

MPC is very sensitive to the change of parameters. The actual filter inductance and parasitic resistance are assumed to be

and

, while

L and

R are used to represent the filter inductance and parasitic resistance used in the mathematical model. Therefore, the errors of filter inductance and parasitic resistance can be expressed as

and

, respectively, and (

2) can be written as:

where

is the predicted current considering the influence of parameter mismatch.

Taking the error on the

-axis as an example, this paper defines it as

, which means the difference between (

2) and (

6).

Substituting (

2) and (

6) into (

7), we can get the following:

For analyzing the error expression, assume that during the current control cycle,

is the optimal vector.

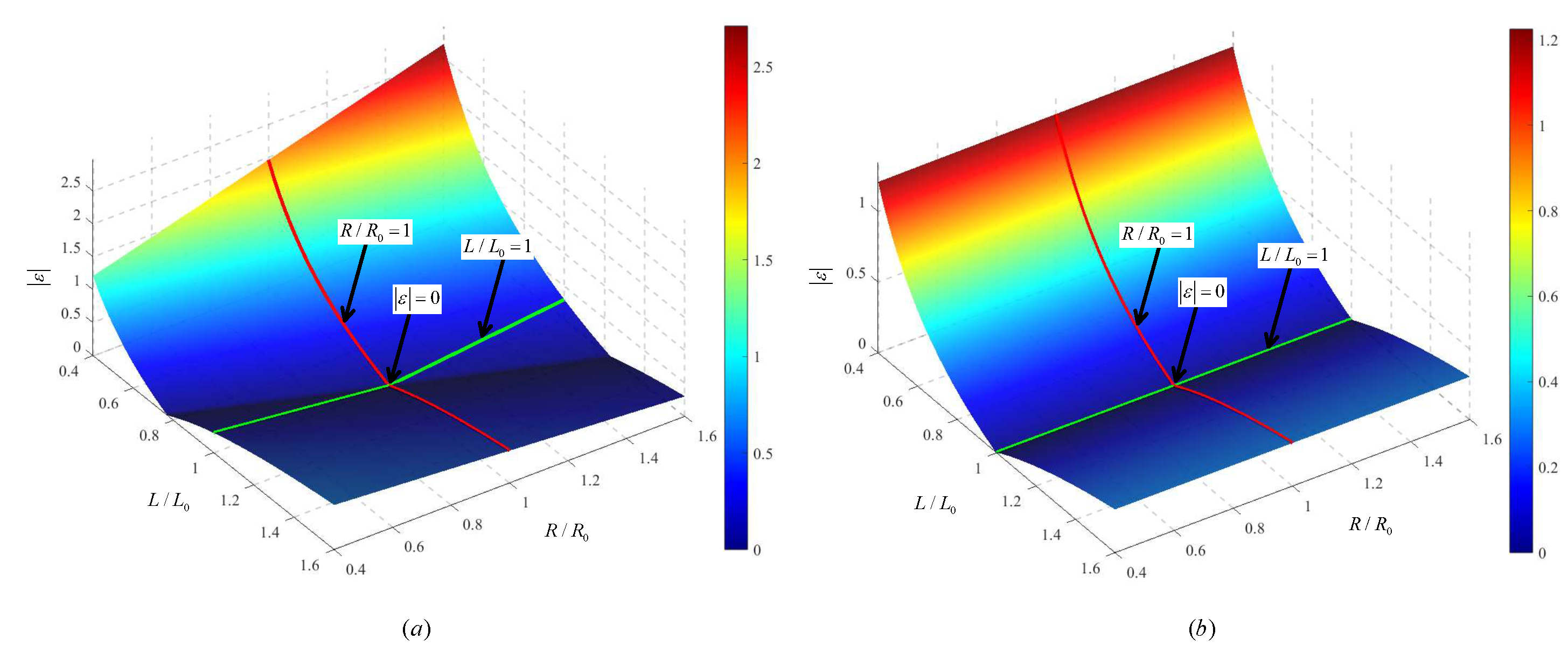

Figure 3 shows the absolute prediction error

under specific parameter combinations:

Figure 3-(a) and

Figure 3-(b) demonstrate that when the parasitic resistance is large (

), resistance parameter mismatch significantly compromises control accuracy. Conversely, when resistance is small (

), the negative impact of resistance mismatch on control accuracy is substantially reduced.

Both

Figure 3-(a) and

Figure 3-(b) reveal that the prediction error

reaches its minimum when the actual inductance matches the modeled inductance (

). Inductance mismatch increases the prediction error

, exhibiting directional dependency: When the actual inductance is smaller than the modeled value (

),

increases sharply; When the actual inductance is larger (

),

also increases but with a slow trend.

3. Proposed Control Strategy

3.1. Ultra-Local Model

To address the reliance of conventional model predictive control on precise mathematical models and its vulnerability to parameter mismatch, this paper introduces the ultra-local model as a solution. This approach completely avoids explicit representation of physical parameters such as inductance and resistance, instead establishing a data-driven nonlinear dynamic relationship that depends solely on system input-output data. This model-free characteristic enables significant advantages in scenarios involving unmodeled dynamics or parametric perturbations.

For a typical first-order dynamic system, its ultra-local model can be expressed in the following form:

where

x denotes the system output,

is the control input, and

is a design parameter. The critical term

, serving as a lumped representation of unknown dynamics, encompasses in real-time the effects of all unmodeled dynamics, external disturbances, and parameter variations. By estimating the time-varying characteristics of

online, this model adaptively compensates control deviations induced by model mismatch. This mechanism fundamentally eliminates the stringent requirement for parameter accuracy in conventional MPC.

Building on [

23], this paper constructs the ultra-local model for a 2L-inverter. While considering practical system parameter deviations, the system equation can be written as:

According to (

9) and (

10), the ultra-local model of 2L-inverter can be further derived, as shown in (

11):

where

is the lumped disturbance of the system ;

is a non-physical parameter of 2L-inverter. The prediction model in (

2) can be rewritten as:

Under parameter mismatch, the values of and deviate, but encapsulates various errors and disturbances with real-time updating. Consequently, the system maintains robust control performance through despite parameter mismatch. This makes accurate calculation of critically important.

To estimate the lumped disturbance term

in real-time without relying on system parameters, existing studies widely adopt algebraic identification techniques (Algebraic-MFPC). Processed via the composite trapezoidal formula [

24],

is calculated as:

where

,

is the number of control cycles. Its value needs to be weighed between computational efficiency and estimation accuracy. Engineering practice shows that the reasonable value range of

is 8 12. An excessively large

leads to a significant increase in computational burden, while an overly small

reduces the accuracy of disturbance estimation due to insufficient data samples. Traditional algebraic identification requires iterative calculations based on historical data. When the reference command undergoes a step change, a large data window introduces inertial delay, limiting the tracking response speed of

. Optimizing

merely achieves a trade-off between computational complexity and steady-state accuracy without fundamentally improving the response speed during transient processes.

3.2. Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Observer

To address the inherent limitations of algebraic methods, a strategy using a sliding mode observer (SMO) to estimate the dynamic component was proposed in [

25]. However, this approach introduces chattering into the control system, adversely affecting both dynamic and steady-state performance [

26]. The super-twisting sliding mode algorithm (STSMO), a second-order sliding mode technique proposed by Levant [

27], effectively suppresses chattering while preserving the strong robustness of conventional SMO. This is achieved by transferring the high-frequency switching discontinuity from the control signal

u to its derivative

.

The STSMO design requires only the sliding surface information and is directly applicable when the relative degree of the system with respect to the sliding variable is 1. However, a key challenge hinders its practical application: difficulty in parameter tuning due to the typically unknown precise boundaries of the dynamic component.

To meet the requirements of model-free predictive current control for 2L- inverters, this section proposes an improved observer design with two key modifications:

(1) Replacing linear error feedback with an exponential adaptive law, where this nonlinear regulation mechanism significantly enhances transient response performance;

(2) Substituting the sign function with a hyperbolic tangent function (tanh) to achieve smooth chattering suppression. Building on these improvements, we construct a three-level cascade-structured adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer (ASTSMO) governed by the following dynamic equations:

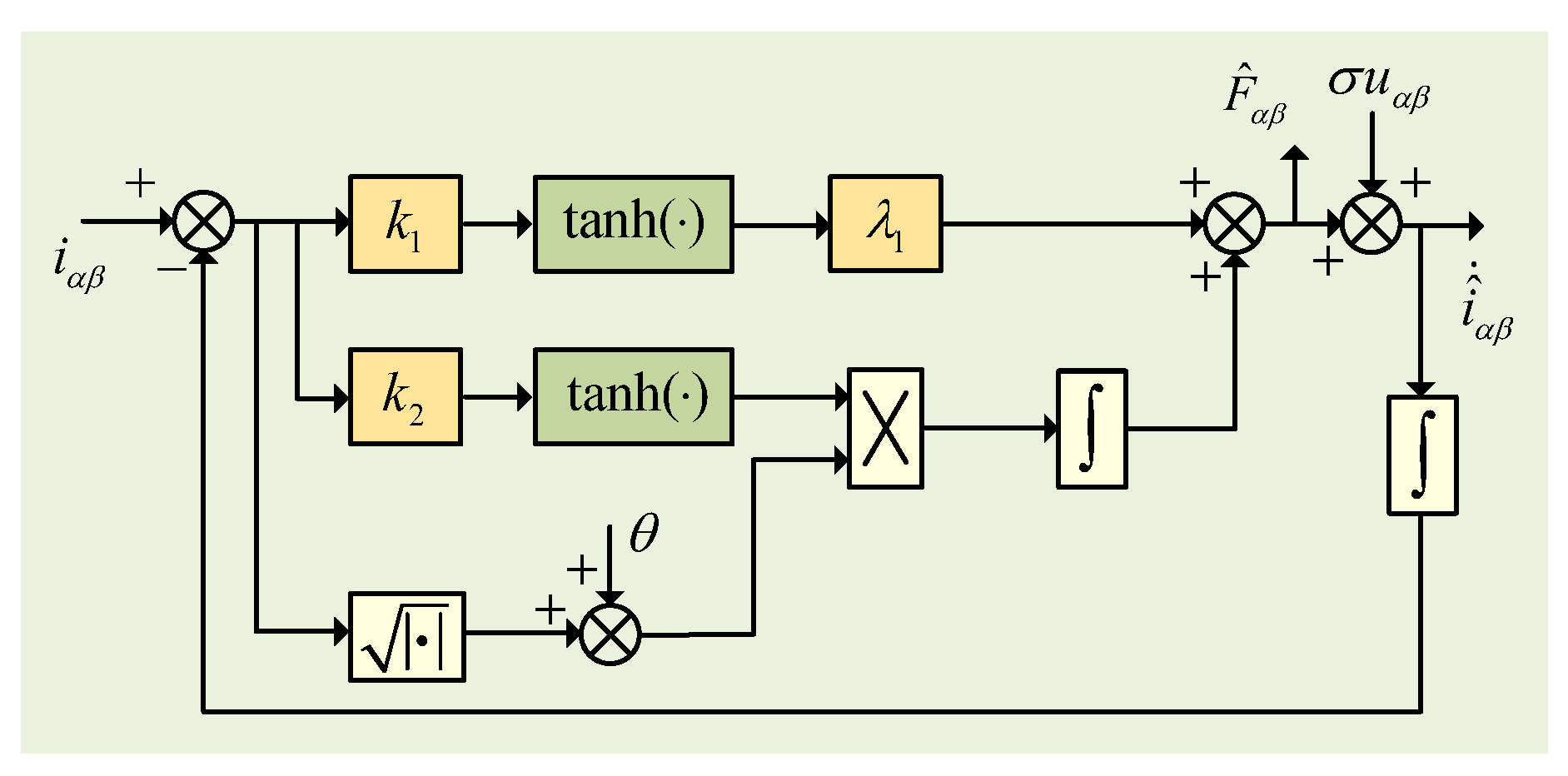

where

is the observed value of current;

, denotes current observation error;

represents the control input voltage ;

is a fixed gain coefficient, taking a positive real number ;

,

is the nonlinear adjustment coefficient, positive real number;

is a time-varying adaptive gain.

Firstly, The current observation error e is entered into the hyperbolic tangent function processing layer; constitutes a proportional channel to generate a fast response component; constitutes an adaptive integral channel to generate a disturbance tracking component ; the estimated value of the disturbance is output after the two channels are superimposed.

The time-varying adaptive gain

is designed as:

where

is the adaptive adjustment coefficient (

> 0);

is the basic gain term (

> 0). When

increases : the gain

increases automatically, enhancing the anti-interference ability. When

decreases : the

decreases automatically to avoid overshoot oscillation.

After the observer converges, the lumped disturbance estimate is :

The structure diagram of the adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer designed according to (

Section 3.2) - (

16) is shown in

Figure 4.

3.3. Stability Proof

Proposition 1: For the adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer defined by (

Section 3.2), the observer error

e converges to zero in finite time when the following conditions hold:

a. The lumped disturbance is bounded, i.e., there exists a constant such that for all t;

b. The gain parameters satisfy , , ;

c. The nonlinear regulation coefficients , are sufficiently large.

Proof. From the ultra-local model (

9) and observer equation (14)-(a), the observer error dynamics yields:

The Lyapunov function is constructed as (

19), V is a positive definite function.

where

is the lower bound of the ideal gain, satisfying

The adaptive gain derivation of (

15) :

Since

is singular at

, a regularization factor needs to be introduced. Let

,

be small constants greater than 0.

brings (

18), (

21) and (

23) into (

20):

The following proves that it converges in finite time, using three inequalities to scale:

The conditions for the establishment of (25)-(a) are: when

is close to 0,

; The validity of (25)-(b) can be proven by using Young’s inequality; Under parameter condition

, (25)-(c) can be proven to hold. Combining (25)-(a) - (25)-(c) and selecting sufficiently large

and

, we obtain:

By (25)-(c), we know that

v is bounded and take :

Then there exists

such that :

According to the finite-time stability theorem, the observer error e converges to zero in finite time .

3.4. ASTSMO-MFPC Strategy

Substitute

with the dynamically estimated term

obtained from the stabilized ASTSMO into (

12), and consider delay compensation:

The cost function defined in (

5) is still employed for receding-horizon optimization. In summary, the block diagram of the proposed adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer-based model-free predictive control for inverter is shown in

Figure 5.

The execution flow of this control algorithm comprises three main steps: First, the adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer estimates the dynamic component of the inverter’s ultra-local model in real-time; Second, the obtained estimate is substituted into the prediction model equation to compute the predicted state at the next sampling instant, followed by global optimization calculation based on the predefined cost function; Finally, the optimal voltage vector that minimizes the cost function value is selected to generate corresponding switching signals. This control strategy requires no precise physical parameters of the inverter system, thus exhibiting remarkable robustness.

4. Simulation Verification

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, a simulation model was established and compared with both conventional model predictive current control (MPC) and algebraic-based model-free predictive current control (Algebraic-MFPC). Identical circuit parameters were used for all methods, operating at low voltage levels. Relevant simulation parameters are listed in

Table 2.

4.1. Steady-State Results under Parameter Matching

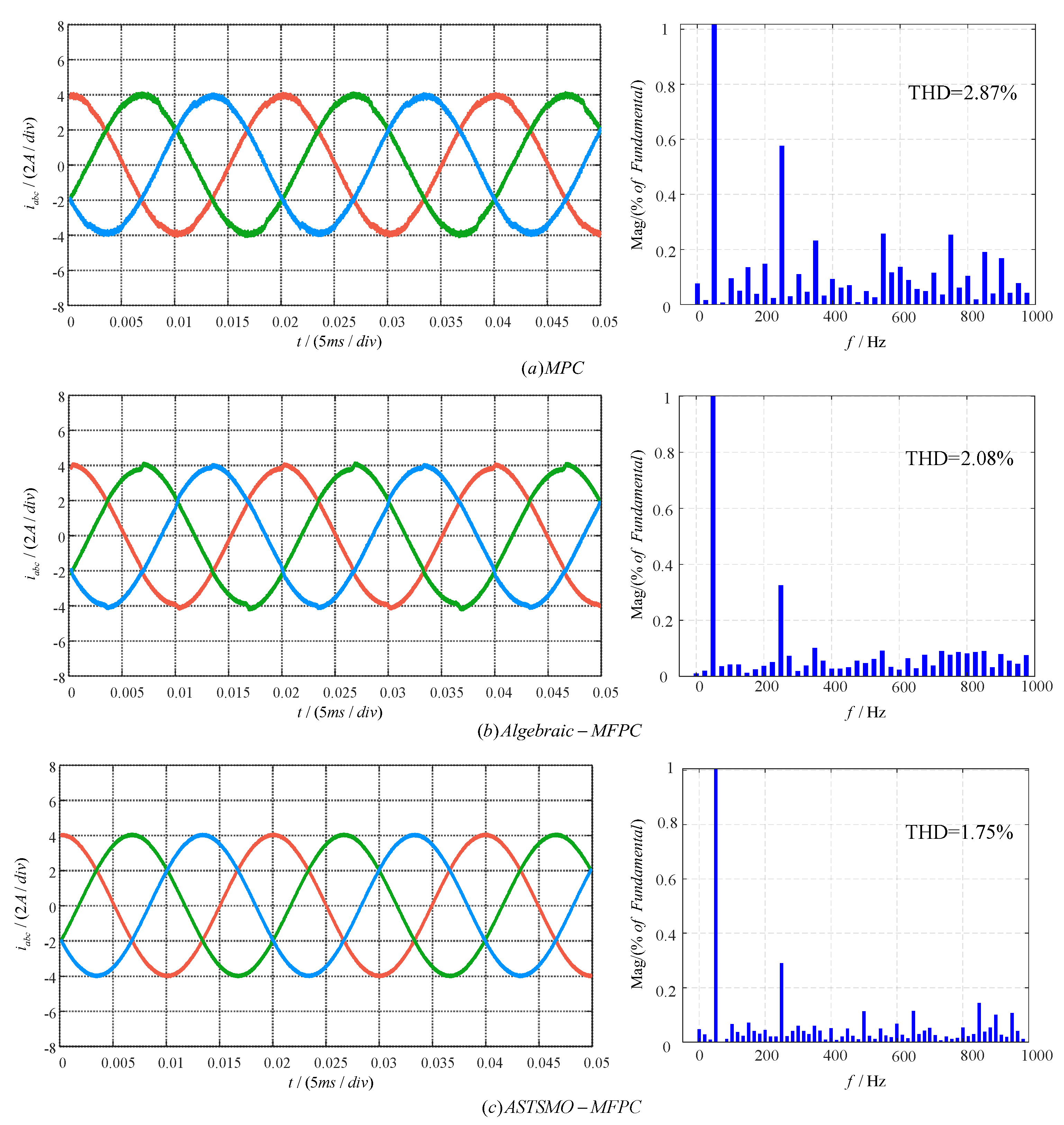

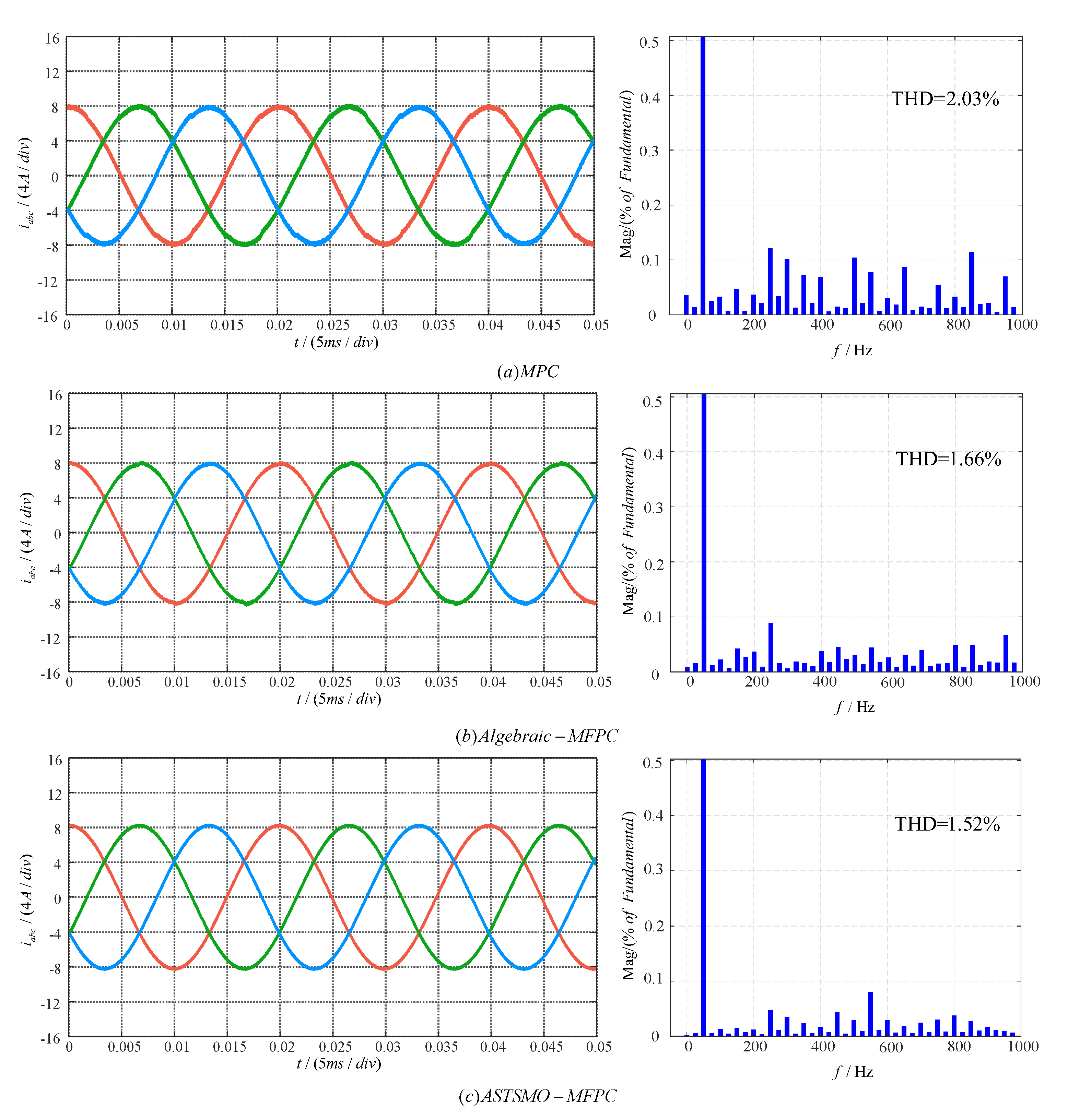

To validate effectiveness, the steady-state performance of the ASTSMO-MFPC was compared via simulations with MPC and Algebraic-MFPC.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the output current waveforms and corresponding total harmonic distortion (THD) analyzes for the three methods at reference currents of 4 A and 8 A, respectively. THD values under varying reference currents are summarized in

Table 3.

Simulation results demonstrate that under parameter-matched conditions, all three strategies achieve steady-state reference current tracking while maintaining THD within industry-accepted standards. Detailed analysis reveals: (1) With accurate parameter matching, MPC delivers acceptable performance meeting basic requirements; (2) Both MFPC methods outperform conventional MPC, as clearly evidenced by

Table 3 data showing significantly lower THD values for MFPC strategy at identical reference currents; (3)

Figure 6 -

Figure 7 indicate that Algebraic-MFPC exhibits slight overshoot at phase peaks, whereas the proposed ASTSMO-MFPC maintains superior current amplitude accuracy with smoother waveforms; (4) Table 3 THD data conclusively proves ASTSMO-MFPC achieves the lowest THD across all tested currents (4–12 A), substantially outperforming both MPC and Algebraic-MFPC. For example, at 8 A, its THD (

) is lower than MPC’s

and Algebraic-MFPC’s

, with this advantage persisting as current increases.

In summary, under parameter-matched conditions, the proposed ASTSMO-MFPC demonstrates optimal performance in both current amplitude accuracy and harmonic suppression (THD reduction).

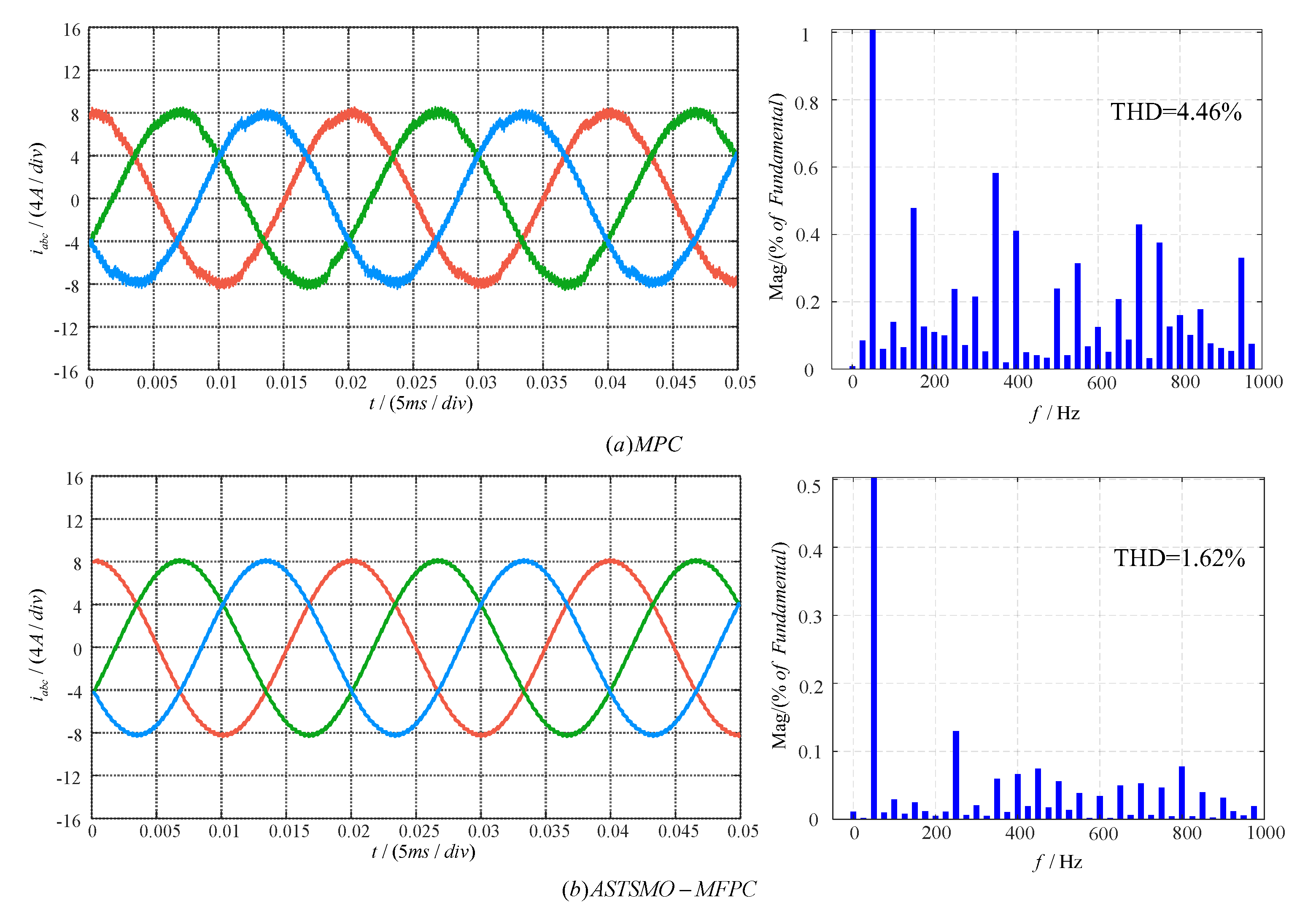

4.2. Results under Parameter Mismatching

To validate the parameter robustness of the proposed method, this paper conducts a comparative study between ASTSMO-MFPC and MPC under model parameter mismatch conditions. The simulation sets the reference current to 8 A and configures the inductance parameter in the control algorithm to half the actual inductance.

Figure 8 displays the output current waveforms of both methods under parameter mismatch. Visually, the MPC output exhibits significant distortion with degraded waveform smoothness and a doubled THD value. In contrast, ASTSMO-MFPC maintains accurate tracking of the reference sinusoidal wave without observable distortion, showing minimal THD variation.

Table 4 presents the THD values of both strategies under parameter mismatch conditions at reference currents ranging from 6 A to 12 A. At each operating point, the MPC strategy exhibits significantly increased THD, while the ASTSMO-MFPC maintains near-constant performance. These results demonstrate that while conventional MPC suffers severe performance degradation under parameter mismatch, the ASTSMO-MFPC method substantially enhances parameter robustness through its observer’s real-time updating of unknown dynamics.

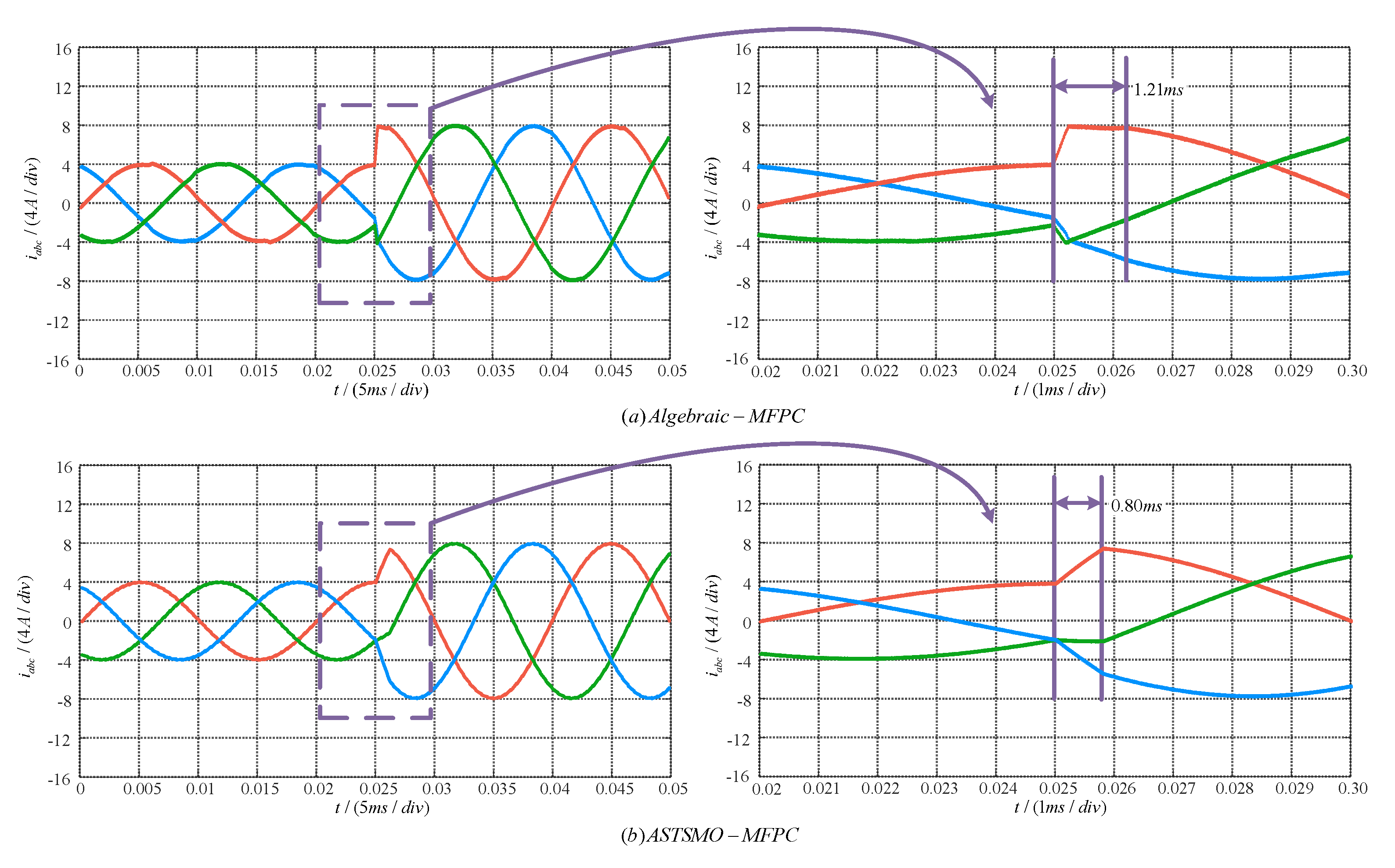

4.3. Results when Reference Current Step

To thoroughly compare the dynamic performance of the proposed ASTSMO-MFPC with Algebraic-MFPC, dynamic tests under reference current step changes were conducted. The test configured the reference current to step-increase from 4 A to 8 A. When the reference current experienced a step change, the response time of Algebraic-MFPC was 1.21 ms. In contrast, ASTSMO-MFPC exhibited faster dynamic response with its response time significantly reduced to 0.80 ms. This indicates a improvement in system response speed compared to the conventional algebraic method, demonstrating substantial dynamic performance advantages.

A core improvement of the proposed method lies in employing ASTSMO to estimate unknown disturbances and unmodeled dynamics within the system. This approach drastically reduces the online computational burden of the control system. The faster response time observed in

Figure 9 directly manifests this computational efficiency enhancement in dynamic performance, thereby enabling the controller to complete predictive optimization calculations and update control actions more rapidly.

To objectively evaluate the computational complexity of the proposed strategy, execution times were measured on an AMD Ryzen5 5600 @ 4.4 GHz simulation platform, enabling quantitative comparison between conventional MPC and the ASTSMO-MFPC strategy. Key findings are summarized as follows: In the control actuation stage, both the proposed ASTSMO-MFPC and conventional MPC require traversing all 8 voltage vectors and iteratively evaluating the cost function. The computational complexity at this stage is comparable (measured mean: 95 s/control cycle). The additional computational overhead primarily originates from the online ASTSMO estimation module (measured mean: 20 s/control cycle), which dynamically updates the coefficients of the ultra-local model. Consequently, the overall computational complexity of the proposed strategy exhibits only a 21% increase compared to conventional MPC (i.e., 115 s vs. 95 s). This marginal computational cost delivers significant performance benefits: It fundamentally eliminates the controller’s dependency on precise model parameters while enhancing parametric robustness, thereby ensuring reliable system operation under parameter mismatches.

5. Conclusions

To address the performance degradation of model predictive control caused by parameter mismatch in three-phase inverter systems, this paper proposes a model-free predictive current control strategy based on an adaptive super-twisting sliding mode observer. This strategy integrates model-free concepts into the predictive framework, replacing traditional physical models with a first-order ultra-local model to fundamentally eliminate reliance on precise parameters. By designing an ASTSMO with adaptive gains to accurately estimate unknown dynamic terms in the ULM in real-time, it significantly enhances disturbance rejection capability. Simultaneously, the adaptive gain mechanism simplifies parameter tuning. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed ASTSMO-MFPC method outperforms conventional MPC and algebraic MFPC in both steady-state harmonic suppression and dynamic response speed. It exhibits stronger parameter robustness and superior comprehensive dynamic-steady-state performance, providing an effective solution for high-performance inverter control under parametric uncertainty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W. Luo and Z. Shu; methodology, W. Luo; validation, W. Luo, Z. Shu and R. Zhang; formal analysis, W. Luo; investigation, W. Luo; data curation, Z. Shu and R. Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, W. Luo, Z. Shu and R. Zhang; writing—review and editing, W. Luo, J. I. Leon and A. M. Alcaide; supervision, L. G. Franquelo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, under grant 62003114, the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang, under grant LH2023F019, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, under grant 2020M681097, the Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Fund, under grant LBH-Z20134, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, under grant HIT.NSFJG202207, and the National Key Laboratory of Laser Spatial Information Foundation, under grant LSI2025WDZC07.

References

- W. Luo, S. Stynski, A. Chub, L. G. Franquelo, M. Malinowski and D. Vinnikov, “Utility-Scale Energy Storage Systems: A Comprehensive Review of Their Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions,” IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 17–27, 2021.

- W. Luo, S. Li, S. Vazquez, J. Du, L. Wu, and L. G. Franquelo, “Grid-connected inverter control via linear parameter-varying system approach,” in IECON 2022 – 48th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- S. Vazquez, D. Marino, E. Zafra, M. D. V. Peña, J. J. Rodríguez-Andina, L. G. Franquelo, and M. Manic, “An artificial intelligence approach for real-time tuning of weighting factors in FCS-MPC for power converters,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 69, no. 12, pp. 11 987–11 998, 2022.

- E. Zafra, J. Granado, V. B. Lecuyer, S. Vazquez, A. M. Alcaide, J. I. Leon, and L. G. Franquelo, “Computationally Efficient Sphere Decoding Algorithm Based on Artificial Neural Networks for Long-Horizon FCS-MPC,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 39–48, 2024.

- Z. Song, Y. Tian, W. Chen, Z. Zou and Z. Chen “Predictive Duty Cycle Control of Three-Phase Active-Front-End Rectifiers,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 698–710, 2015.

- L. Guo, M. Zheng and Y. Li, “Parametric Sliding Mode Predictive Control Strategy for Three-Phase LCL Grid-Connected Inverter,” Power System Protection and Control, vol. 50, no. 8, pp. 72–82, 2021.

- P. R. U. Guazzelli, W. C. Pereira, C. M. R. Oliveira, A. G. Castro, and M. L. Aguiar, “Weighting Factors Optimization of Predictive Torque Control of Induction Motor by Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 6628–6638, 2018.

- X. Shi, J. Zhu, L. Li and D. D. C. Lu, “Model-Predictive-Based Duty Cycle Control with Simplified Calculation and Mutual Influence Elimination for AC/DC Converter,” IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 504–514, 2019.

- X. Shen, J. Liu, G. Liu, J. Zhang, J. I. Leon, L. Wu and L. G. Franquelo, “Finite-Time Sliding Mode Control for NPC Converters with Enhanced Disturbance Compensation,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 1822–1831, 2025.

- Z. Chen, J. Qiu and M. Jin, “Adaptive Finite-Control-Set Model Predictive Current Control for IPMSM Drives with Inductance Variation,” IET Electric Power Applications, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 874–884, 2017.

- C. K. Lin, J. Yu, Y. S. Lai and H. C. Yu, “Improved Model-Free Predictive Current Control for Synchronous Reluctance Motor Drives,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 3942–3953, 2016.

- F. Guo, T. Yang, A. M. Diab, S. S. Yeoh, S. Bozhko and P. Wheeler, “An Enhanced Virtual Space Vector Modulation Scheme of Three-Level NPC Converters for More-Electric-Aircraft Applications,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 5239–5251, 2021.

- F. Michel and J. Cédric, “Model-Free Control,” International Journal of Control, vol. 86, no. 12, pp. 2228–2252, 2013.

- L. Guo, N. Jin, C. Gan and K. Luo, “Hybrid Voltage Vector Preselection-Based Model Predictive Control for Two-Level Voltage Source Inverters to Reduce the Common-Mode Voltage,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 4680–4691, 2019.

- H. Li, X. Li, Z. Chen, J. Mao, J. Huang, “Model-Free Adaptive Integral Backstepping Control for PMSM Drive Systems,” Journal of Power Electronics, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1193–1202, 2019.

- Y. Zhang, T. Jiang and J. Jiao, “Model-Free Predictive Current Control of a DFIG Using an Ultra-Local Model for Grid Synchronization and Power Regulation,” IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 2269–2280, 2020.

- J. Liu, X. Shen, A. M. Alcaide, Y. Yin, J. I. Leon, S. Vazquez, L. Wu and L. G. Franquelo, “Sliding Mode Control of Grid-Connected Neutral-Point-Clamped Converters Via High-Gain Observer,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 4010–4021, 2022.

- Y. Wang, H. Li, R. Liu, L. Yang and X. Wang, “Modulated Model-Free Predictive Control with Minimum Switching Losses for PMSM Drive System,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 20942–20953, 2020.

- Y. L. Cao, J. A. Cao, X. Song and Y. J. Liu, “Research on Vector Control of PMSM Based on an Improved Sliding Mode Observer,” Power System Protection and Control, vol. 49, pp. 104–111, 2021.

- Y. Yin, S. Vazquez, A. Marquez, J. Liu, J. I. Leon, L. Wu, and L. G. Franquelo, “Observer-based sliding-mode control for grid-connected power converters under unbalanced grid conditions,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 517–527, 2022.

- W. Luo, S. Vazquez, J. Liu, F. Gordillo, L. G. Franquelo and L. Wu, “Control System Design of a Three-Phase Active Front End Using a Sliding-Mode Observer,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 739–748, 2020.

- G. Liang, S. Huang, M. D. Li and X. Wu, “A High-Order Fast Terminal Sliding-Mode Disturbance Observer Based on Mechanical Parameter Identification for PMSM,” Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society, vol. 35, no. S2, pp. 395–403, 2020.

- C. Ma, H. Li, X. Yao, Z. Zhang and F. De Belie, “An Improved Model-Free Predictive Current Control with Advanced Current Gradient Updating Mechanism,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 68, no. 12, pp. 11968–11979, 2020.

- F. Li, T. Zheng, N. He and Q. Cao, “Data-Driven Hybrid Neural Fuzzy Network and ARX Modeling Approach to Practical Industrial Process Identification,” IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1702–1705, 2022.

- N. Jin, M. Chen, L. Guo, Y. Li and Y. Chen, “Double-Vector Model-Free Predictive Control Method for Voltage Source Inverter with Visualization Analysis,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 69, no. 10, pp. 10066–10078, 2021.

- J. Liu, L. Wu, C. Wu, W. Luo and L. G. Franquelo, “Event-triggering Dissipative Control of Switched Stochastic Systems via Sliding Mode,” Automatica, vol. 103, pp. 261–273, 2019.

- A. Chalanga, S. Kamal, L. M. Fridman, B. Bandyopadhyay and J. A. Moreno, “Implementation of Super-Twisting Control: Super-Twisting and Higher Order Sliding-Mode Observer-Based Approaches,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 3677–3685, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).