Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- emotional exhaustion (EE), perceived by the individual as an emotional depletion, as if „their reserves are consumed” [1];

- depersonalization (DP), characterized by a subjective feeling of detachment and even diminished empathy [4];

- decreased sense of personal accomplishment (PA), which can distort one’s self-evaluation of their work and leads them to feel less competent than they actually are [5].

- self-awareness: represents an individual’s ability to recognise their own emotions, as well as the impact of those emotions over other people;

- self-management (or self-regulation): assumes the recognition of negative emotions, as well as controlling and forwarding them towards a more productive purpose;

- inner motivation: represents the tendency to be driven by values and passion, not just by external reward;

- social awareness: includes the ability to manage and guide the relationship with others;

- -

- -

- diversity when it comes to cultural and contextual differences regarding work ethic, work-life balance, or the approach of expressing feelings in certain regions. In the context of obtaining most of the data used by self-administered questionnaires, the cultural stigma or reveal bias may be an important contributor to the accuracy of data. The individualistic vs. collectivist models can also shape the way not only work is perceived, but also how individuals tend to seek or receive support and guidance [30].

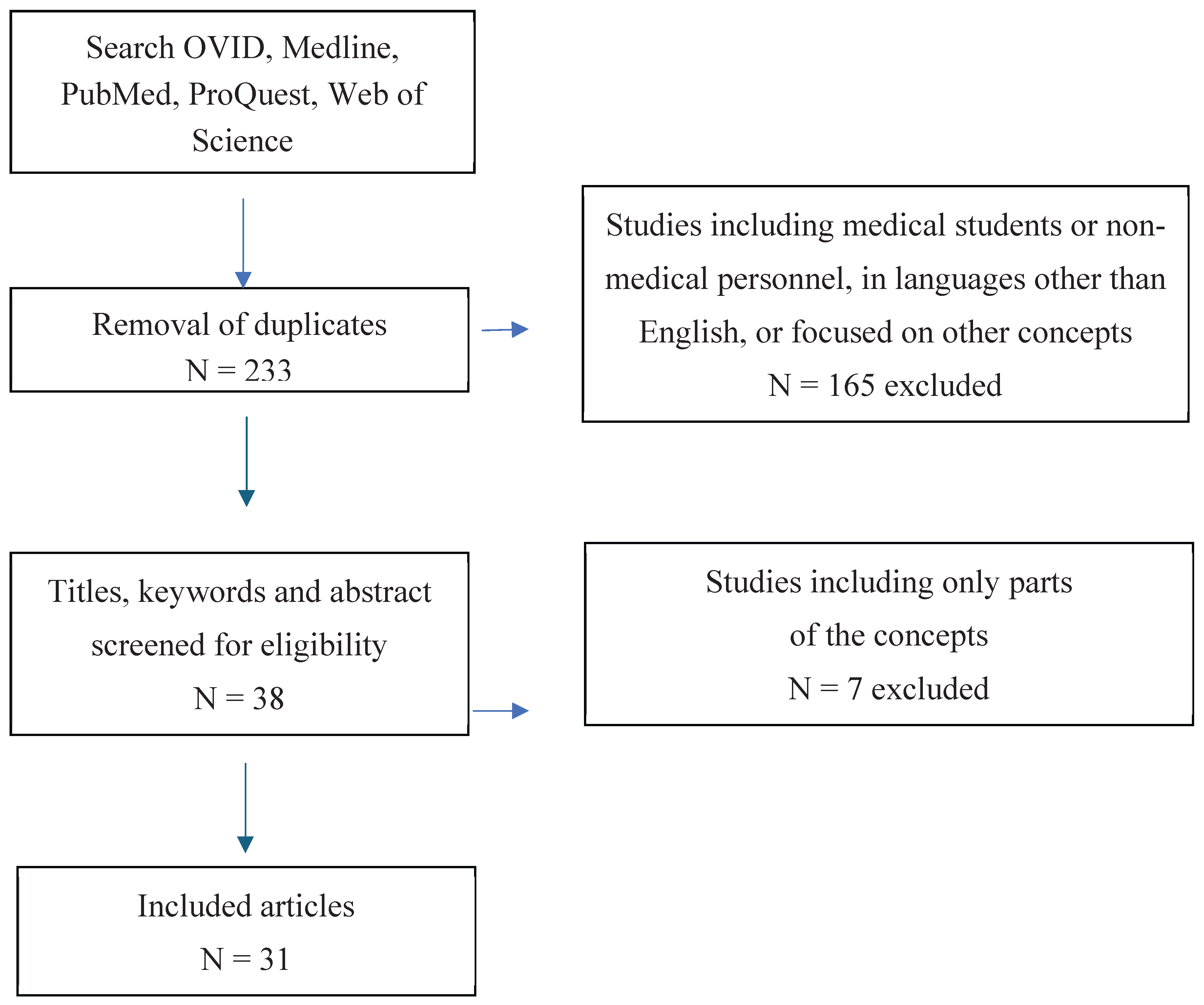

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Findings

3.2. RQ1: What Is the Burnout Prevalence Among Healthcare Professionals and Which Are the Main Contributing Factors to Burnout?

3.3. RQ 2: Does Emotional Intelligence Play a Role in Protecting Against Burnout?

3.4. RQ 3: Which Additional Factors Influence EI in Healthcare Workers?

4. Discussion

4.1. Burnout Prevalence and Variability

4.2. Protective Role of EI

4.3. Factors Influencing EI

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| EE | Emotional Exhaustion |

| DP | Depersonalization |

| PA | Personal Accomplishment |

| PO | Psychological Ownership |

References

- Grow, H.M.; McPhillips, H.A.; Batra, M. Understanding physician burnout. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2019, 49, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, R.; Oluwasina, F.; Eboreime, E.; El Gindi, H.; Agyapong, B.; Hrabok, M.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Burnout among residents: Prevalence and predictors of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion and professional unfulfillment among resident doctors in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Medical Teacher 2017, 39, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Preventing and Managing Burnout: What have we learned. Biomedical Journal 2018, 2, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Scarecrow Education 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tavella, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Parker, G. Burnout: Redefining its key symptoms. Psychiatry Research 2021, 302, 114023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, J.G.; Khan, Z.; Babu, M.; Hamed, O. Stress, burnout, and maladaptive coping. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons 2011, 96, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Canu, I.G.; Marca, S.C.; Dell’Oro, F.; Balázs, Á.; Bergamaschi, E.; Besse, C.; Wahlen, A. Harmonized definition of occupational burnout: A systematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2021, 47, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Burnout and doctors: Prevalence, prevention and intervention. Healthcare 2016, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa-Velea, O.; Diaconescu, L.V.; Gheorghe, I.R.; Olariu, O.; Panaitiu, I.; Cerniţanu, M.; Spinei, L. Factors associated with burnout in medical academia: An exploratory analysis of Romanian and Moldavian physicians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genly, B. Safety and job burnout: Understanding complex contributing factors. Professional Safety 2016, 61, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, N.; Karayiannis, P. N.; Convie, L.; Clarke, M.; Kirk, S. J.; Campbell, W.J. Resilience in medical doctors: a systematic review. Postgraduate medical journal, 95. [CrossRef]

- Bria, M.; Băban, A.; Dumitraşcu, D.L. Systematic review of burnout risk factors among European healthcare professionals. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2012, 16, 423–452. [Google Scholar]

- Renger, D.; Miché, M.; Casini, A. Professional Recognition at Work: The Protective Role of Esteem, Respect, and Care for Burnout Among Employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020, 62, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, R.; Raghuvanshi, J. Do values reflect what is important? Exploring the nexus between work values, work engagement and job burnout, International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2023, 31, 1414-1434. [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Duan, Z.; Zhan, K.; Lu, H.; Chen, X. Non-linear association of years of experience and burnout among nursing staff: a restricted cubic spline analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 1343; 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, N.R.F.; de Santana, A.N.; Bueno, J.M.H. The relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence: A meta-analysis. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho 2023, 23, 2471–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Taieb, O.; Xavier, S.; Baubet, T.; Reyre, A. The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: A systematic review. Explore 2020, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hricová, M. The mediating role of self-care activities in the stress-burnout relationship. Health Psychology Report 2020, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.Y.H.; Khoo, H.S.; Gallardo, M.D.; Hum, A. How leaders, teams and organisations can prevent burnout and build resilience: A thematic analysis. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2020, 14, e827–e836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-L.; Yeap, P.F. The impact of work engagement and meaningful work to alleviate job burnout among social workers in New Zealand”, Management Decision, 2022, 60, 3042-3065. [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J.; Deane, F.P.; Anderson, S. Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences 2002, 32, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.R.; Khoshsima, H.; Zare-Behtash, E. The impacts of enhancing emotional intelligence on the development of reading skill. International Journal of Instruction 2018, 11, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanesan, P.; Fauzan, N. Models of emotional intelligence: A review. e-BANGI Journal 2019, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Gaschke, Y.N. The experience and meta-experience of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 55, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Gomberg-Kaufman, S.; Blainey, K. A broader conception of mood experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1991, 60, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. N: Bantam Books, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence: Issues in paradigm building. The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace 2001, 13, 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, G. Big five model personality traits and job burnout: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychology 2023, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listopad, I.W.; Michaelsen, M.M.; Werdecker, L.; Esch, T. Bio-psycho-socio-spirito-cultural factors of burnout: A systematic narrative review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 722862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, M. Preventing Burnout: Controlling Emotions, the Right Way. Master’s thesis, Lamar University-Beaumont.

- Kadadi, S.; Bharamanaikar, S.R. Role of emotional intelligence in healthcare industry. Drishtikon: A Management Journal 2020, 11, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru-Luna, L.M.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Cervera-Santiago, J.L. Emotional intelligence measures: A systematic review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Gao, L.; Fan, L.; Jiao, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y. The influence of emotional intelligence on job burnout of healthcare workers and mediating role of workplace violence: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 892421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Sambasivan, M.; Kumar, N. Effect of spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence, psychological ownership and burnout on caring behaviour of nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2013, 22, 3192–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, B.; Petrusa, E.; McKinley, S.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Gee, D.; Smink, D.S.; Phitayakorn, R. Association of burnout with emotional intelligence and personality in surgical residents: Can we predict who is most at risk? Journal of Surgical Education 2017, 74, e22–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofer, K.D.; Hollis, R.H.; Goss, L.; Morris, M.S.; Porterfield, J.R.; Chu, D.I. Burnout is associated with emotional intelligence but not traditional job performance measurements in surgical residents. Journal of Surgical Education 2018, 75, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, Z. The contribution of emotional intelligence on the components of burnout: The case of health care sector professionals. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies 2014, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Simón Márquez, M.D.M.; Martos Martínez, Á. Burnout risk and protection factors in certified nursing aides. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeneessier, A.S.; Azer, S.A. Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University. BMC Medical Education 2023, 23, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemy, Z.A.; Sharif, A.F.; Bahgat, N.M.; Abdelsattar, S.; Latif, A.A.A. Emotional intelligence, workplace conflict and job burn-out among critical care physicians: A mediation analysis with a cross-sectional study design in Egypt. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Năstasă, L.E.; Fărcaş, A.D. The effect of emotional intelligence on burnout in healthcare professionals. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 187, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Analysis of the risk and protective roles of work-related and individual variables in burnout syndrome in nurses. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, J.; Swenson, S.; Rabow, M. Emotional intelligence in internal medicine residents: Educational implications for clinical performance and burnout. Annals of Behavioral Science and Medical Education 2009, 14, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, F.; Baker, S.J.; Wood, T.; Wood, L.; Hollis, R.H.; Chu, D.I.; Lindeman, B. Emotional intelligence and burnout in surgical residents: A 5-year study. Journal of Surgical Education 2020, 77, e63–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, I.; Reddy, K.J. Relationship of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout among MBBS Doctors of Himachal Pradesh. Indian Journal of Psychological Science 2022, 15, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou, E.M.; Damigos, D.; Lyrakos, G.; Chanopoulos, K.; Kosmidis, G.; Karavis, M. The relationship between burnout syndrome and emotional intelligence in healthcare professionals. Health Science Journal 2016, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arnone, R.; Cascio, M.I.; Parenti, I. The role of Emotional Intelligence in health care professionals burnout. European Journal of Public Health 2019, 29, 186–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgens-Ekermans, G.; Brand, T. Emotional intelligence as a moderator in the stress-burnout relationship: A questionnaire study on nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2012, 21, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygiel, D.D.; Mikolajczak, M. Emotional intelligence buffers the effects of negative emotions on job burnout in nursing. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Bhagat, D. The role of emotional intelligence on health care professionals occupational stress and burnout. International Journal of Current Research and Review 2020, 12, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaei, S.E.; Khosravi, Y.; Heravizadeh, O.; Ahangar, H.G.; Pourshariati, F.; Amrollahi, M. The effect of emotional intelligence and job stress on burnout: A structural equation model among hospital nurses. International Journal of Occupational Hygiene 2017, 9, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Beierle, S.P.; Kirkpatrick, B.A.; Heidel, R.E.; Russ, A.; Ramshaw, B.; McCallum, R.S.; Lewis, J.M. Evaluating and exploring variations in surgical resident emotional intelligence and burnout. Journal of Surgical Education 2019, 76, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, A.; Wan, H. The mediating role of emotion management, self-efficacy and emotional intelligence in clinical nurses related to negative psychology and burnout. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2023, 16, 3333–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, M.K.; Mathur, D.M.; Pushp, B.K. Emotional intelligence, perceived stress and burnout among resident doctors: An assessment of the relationship. The National Medical Journal of India 2013, 26, 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.C.; Hung, C.M.; Liu, Y.T.; Cheng, Y.J.; Yen, C.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Huang, C.K. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. Medical Education 2011, 45, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Sarkar, A.P.; Haldar, D.; Saren, A.B.; Lo, S.; Sarkar, G.N. Correlation among perceived stress, emotional intelligence, and burnout of resident doctors in a medical college of West Bengal: A mediation analysis. Indian Journal of Public Health 2018, 62, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, Z.; Parveen, S.; Khizar, U. Self-control as mediator between emotional intelligence and burnout among doctors. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2023, 7, 388–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Dahmash, A.; Alhadlaq, A.S.; Alhujayri, A.K.; Alkholaiwi, F. , Alosaimi, N.A. (2019). Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Plastic Surgery Residents: Is There a Relationship? Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open 2019, 7, e2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, H.; Wasfie, T.; Laykova, A.; Barber, K.; Hella, J.; Vogel, M. Emotional intelligence, burnout, and wellbeing among residents as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Surgeon 2022, 88, 1856–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasfie, T.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Barber, K.; Hella, J.R.; Anderson, T.; Vogel, M. Burnout and well-being of medical and surgical residents in relation to emotional intelligence: A 3-year study. Surgery 2024, 175, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, A.M.; Abdulla, I.H.; Alnatheer, A.M.; Alahmari, A.N.; Alwhibi, O.A.; Alabduljabbar, Z.; Alkholaiwi, F.M. Emotional intelligence and burnout among otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery residents. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 851408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasfie, T.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Barber, K.; Hella, J.R.; Anderson, T.; Vogel, M. Longitudinal study of emotional intelligence, well-being, and burnout of surgical and medical residents. The American Surgeon 2023, 89, 3077–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, S.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Martin, A. Psychological ownership: A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2017, 38, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, A.; Abaeva, O.; Prisyazhnaya, N.; Romanova, T.; Romanov, S.; Sobolev, K.; Manukyan, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout Levels among Healthcare Workers: A Comparative Analysis of the Pandemic Period and Post-Pandemic Period. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Burn-out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. WHO. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 01.07.2025).

- Goldberg, D.G.; Soylu, T.; Hoffman, C.F.; Kishton, R.E.; Cronholm, P.F. “Anxiety, COVID, Burnout and Now Depression”: A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Clinicians’ Perceptions of Burnout. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39(8), 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Di Bianca, M. Help-Seeking for Depression as a Stigmatized Threat to Masculinity. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 2021, 52, (2), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.J.; Ho, M.-H.R.; Wang, S.-Y.; Miller, I.S.K. Meta-Analyses of the Relationship between Conformity to Masculine Norms and Mental Health-Related Outcomes. Journal of Counselling Psychology 2017, 64(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, E.W.; Shapard, L. Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review 2004, 3, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Vargas, C.; De la Fuente, E.I.; Fernández-Castillo, R.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Age as a risk factor for burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: A meta-analytic study. Research in Nursing & Health 2017, 40, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, L.; van der Vaart, L.; Stemmet, L. Positive Psychological Interventions Aimed at Enhancing Psychological Ownership. In Theoretical Orientations and Practical Applications of Psychological Ownership. In Theoretical Orientations and Practical Applications of Psychological Ownership; Publisher: Place, Country, 2017; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, K.; Muller Neff, D.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Luo, J.; Briley, D.A.; Chow, P.I.; Su, R.; Hill, P.L. A Systematic Review of Personality Trait Change Through Intervention. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143(2), 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-I.; Hsu, W.-H. The Impact of Health Service Provider Agreeableness on Care Quality Variation. Serv. Sci. 2012, 4(4), 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.C.; Hsu, C.W.; Chang, C.H.; Tseng, P.T.; Chang, K.V. Effectiveness of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation for Reducing Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2022, 13, 883251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Ortega, E.; Ramirez-Baena, L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Vargas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Gender, marital status, and children as risk factors for burnout in nurses: A meta-analytic study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksson, U.; Graneheim, U.H.; Richter, J.; Eisemann, M.; Åström, S. Exposure to violence in relation to personality traits, coping abilities, and burnout among caregivers in nursing homes: A case-control study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 2008, 22, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converso, D.; Sottimano, I.; Balducci, C. Violence exposure and burnout in healthcare sector: Mediating role of work ability. La Medicina del Lavoro 2021, 112, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somani, R.; Muntaner, C.; Hillan, E.; Velonis, A.J.; Smith, P. A Systematic Review: Effectiveness of Interventions to De-escalate Workplace Violence against Nurses in Healthcare Settings. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.P. Workplace Violence against Health Care Workers in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C. The Promotion of Technology Acceptance and Work Engagement in Industry 4.0: From Personal Resources to Information and Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegling, A.B.; Vesely, A.K.; Petrides, K.V.; Saklofske, D.H. Incremental validity of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire-short form (TEIQue-SF). Journal of Personality Assessment 2015, 97, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ridder, D.T.; Lensvelt-Mulders, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Stok, F.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2012, 16, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, V.; Kraiger, K. Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Human Resource Management Review, 2019, 29, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; Andreatta, R.; Woltenberg, L.; Cormier, M.; Hoch, J.M. The relationship of emotional intelligence to burnout and related factors in healthcare profession students, Nurse Education Today, 2024, 143, 106387. [CrossRef]

- Cabello, R.; Sorrel, M.A.; Fernández-Pinto, I.; Extremera, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Age and gender differences in ability emotional intelligence in adults: A cross-sectional study. Developmental Psychology 2016, 52, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Shipley, N.; Jackson, M.; Segrest, S.; Sharma, D.; Chapman, B.P.; Hayslip, B. Emotional intelligence: A comparative study on age and gender differences. International Journal of Basic and Applied Research 2018, 8, 670–681. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Zafra, E.; Gartzia, L. Perceptions of gender differences in self-report measures of emotional intelligence. Sex Roles 2014, 70, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariselli, L.; Ghini, M.; Freeman, J. (2008). Age and emotional intelligence: white paper. http://www.6seconds.org/sei/media/WP_EQ_and_Age.pdf (Accessed at th, 2025). 8 April.

- Sanchez-Gomez, M.; Breso, E.; Giorgi, G. Could Emotional Intelligence Ability Predict Salary? A Cross-Sectional Study in a Multioccupational Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Vanuk, J.R.; Persich, M.R.; Cloonan, S.A.; Grandner, M.A.; Dailey, N.S. Sleep quality and duration are associated with greater trait emotional intelligence. Sleep Health 2022, 8, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepdanius, E.; Harefa, S.K.; Indika, P.M.; Effendi, H.; Rifki, M.S.; Afriani, R. Relationship between physical activity, stress and sleep quality and emotional intelligence. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences 2023, 11, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acebes-Sánchez, J.; Diez-Vega, I.; Esteban-Gonzalo, S.; Rodríguez-Romo, G. Physical Activity and Emotional Intelligence among Undergraduate Students: A Correlational Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Study title | Authors, position in Reference list | Year | Country | Study design | Sample size | Type of personnel | Instruments used for measuring Burnout | Instruments used for measuring EI | Correlations between Burnout and EI | Factors contributing to Burnout | Modulating factors for EI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Job Burnout of Healthcare Workers and Mediating Role of Workplace Violence: A Cross-Sectional Study | Cao, Y., Gao, L., Fan, L., Jiao, M., Li, Y., & Ma, Y. [35] | 2022 | China | Cross-sectional | 2061 | Physician, nurses, and medical technicians | MBI-GS | EIS | EI was significantly negatively associated with all three dimensions of job burnout | Exposure to violence is corelated with higher burnout | Female gender significantly corelated with higher EI |

| 2 | Effect of spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence, psychological ownership and burnout on caring behaviour of nurses: a cross-sectional study | Kaur, D., Sambasivan, M., Kumar, N. [36] | 2013 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 550 | Nurses | MBI-HSS | SSEIT | Nurses with higher levels of EI suffer lesser levels of burnout | Psychological ownership corelates with lower levels of burnout | Spiritual intelligence influences EI |

| 3 | Association of Burnout With Emotional Intelligence and Personality in Surgical Residents: Can We Predict Who Is Most at Risk? | Lindeman, B., Petrusa, E., McKinley, S., Hashimoto, D. A., Gee, D., Smink, D. S., ... & Phitayakorn, R. [37] | 2017 | United States | Longitudinal cohort | 143 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | Burnout scores were significantly inversely correlated with all 4 facets of EI and EI total | Female sex and older age are associated with higher burnout levels Agreeableness and positive work experiences was inversely corelated with burnout | EI global scores decrease significantly with age |

| 4 | Burnout is Associated With Emotional Intelligence but not Traditional Job Performance Measurements in Surgical Residents | Cofer, K. D., Hollis, R. H., Goss, L., Morris, M. S., Porterfield, J. R., Chu, D. I. [38] | 2018 | United States | Cross-sectional | 40 | Resident doctors | MBI-HSS | TEIQ-SF | The mean EI scores were lower in residents with burnout versus residents without burnout | ||

| 5 | The Contribution of Emotional Intelligence on the Components of Burnout: The Case of Health Care Sector Professionals | Ünal, Z [39] | 2014 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 136 | Trainees, interns, nurses and doctors | MBI | EIS | EI has a positive contribution on PA whereas negative contribution on EE and DP | Married individuals report lower levels of burnout | |

| 6 | Burnout Risk and Protection Factors in Certified Nursing Aides | Molero Jurado, M. D. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. D.C., Gázquez Linares, J.J.G., Simón Márquez, M. D.M., Martos Martínez, Á. [40] | 2018 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 278 | Nurses | CBB | EQ-i-20M | Burnout Syndrome score is significantly related negatively with all the EI factors | Lower age is linked to a higher burnout risk, the group of professionals with a permanent contract showed a significantly higher mean score in burnout | |

| 7 | Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University | Almeneessier, A.S., Azer, S. A. [41] | 2023 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 126 | Medical academics, doctors | MBI-HSS | TEIQ-SF | There is an inverse interrelation was reported between burnout and EI | Workplace risk factors for burnout: workload, job control, lack of a supportive environment, recognition and rewards, equitability, and organizational values | In contrast with other studies, we reported EI and its elements higher in men than in women, which can be explained based on cultural differences |

| 8 | Emotional intelligence, workplace conflict and job burn-out among critical care physicians: a mediation analysis with a cross-sectional study design in Egypt | Kasemy, Z. A., Sharif, A. F., Bahgat, N.M., Abdelsattar, S., Latif, A.A. A. [42] | 2023 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 144 | Doctors | MBI | TEIQ | EI could significantly predict job burn-out across various dimensions, and it showed EI showed a negative association with EE, depersonalisation, and reduced personal achievement. | Age and years of experience, conflict management skills and CoQ10 levels have a negative correlation with burnout Exposure to violence and inadequate resources and facilities had a positive correlation with burnout levels | Conflict management and CoQ10 levels exhibited positive correlations with EI |

| 9 | The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Burnout in Healthcare Professionals | Năstasă, L. E., Fărcaş, A. D. [43] | 2015 | Romania | Cross-sectional | 120 | Doctors and nurses | MBI | EIS | The level of burnout experienced by the medical personnel did not correlate with the level of EI development. | The burnout syndrome is felt more acutely by women | |

| 10 | Analysis of the Risk and Protective Roles of Work-Related and Individual Variables in Burnout Syndrome in Nurses | Pérez-Fuentes, M. D.C., Molero Jurado, M. D.M., Martos Martínez, Á., Gázquez Linares, J. J. [44] | 2019 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 1236 | Nurses | CBB | EQ-I-M20 | There was a negative association between burnout and various factors of EI | Spending more time with colleagues and patients and reporting good-quality relationships exhibit a negative relationship with burnout Nurses with permanent contracts had a higher mean score for burnout than those on temporary contracts | |

| 11 | Emotional Intelligence in Internal Medicine Residents: Educational Implications for Clinical Performance and Burnout | Satterfield, J., Swenson, S., Rabow, M. [45] | 2010 | United States | Cross-sectional | 28 | Resident doctors | The Tedium Index | EIS | EI scores increased over the course of an academic year and higher year-end scores correlated with less burnout and higher overall clinical performance and interviewing ratings. | ||

| 12 | Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Psychosocial Risks on Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Nurses’ Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Soto-Rubio, A., Giménez-Espert, M.D.C., Prado-Gascó, V. [46] | 2020 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 125 | Nurses | CESQT | TMMS-24 | The emotional repair component stands out as an element of EI that should be enhanced to prevent the possible adverse effects of psychosocial risks on nurses, specifically those related to burnout, psychosomatic complaints, and job satisfaction. | ||

| 13 | Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Surgical Residents: A 5-Year Study | Gleason, F., Baker, S.J., Wood, T., Wood, L., Hollis, R.H., Chu, D.I., Lindeman, B. [47] | 2020 | United States | Longitu-dinal cohort | 236 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | Burnout scores showed significant inverse correlation with the 4 domains of EI, total job resources score, and all 4 sub-domains of job resources. | Individuals who were subjected to disruptive behaviors (particularly others taking credit for work and public humiliation) were more likely to experience higher burnout levels Each additional PGY year demonstrated an incremental increase in burnout | |

| 14 | Relationship of Emotional Intelligence and Burnout among MBBS Doctors of Himachal Pradesh | Kaul, I., Reddy, K.J. [48] | 2022 | India | Cross-sectional | 190 | Doctors | MBI | SSEIT | A highly negative correlation is found between EI, EE and DP, and a positive correlation between EI and PA | ||

| 15 | The Relationship between Burnout Syndrome and Emotional Intelligence in Healthcare Professionals | Vlachou, E. M., Damigos, D., Lyrakos, G., Chanopoulos, K., Kosmidis, G., Karavis, M. [49] | 2016 | Greece | Cross-sectional | 148 | Doctors, nurses, physical therapists | MBI | TEIQ-SF | There is a positive relationship between EI and Burnout syndrome as EI acts protectively against Burnout syndrome and even reduces it | ||

| 16 | The role of Emotional Intelligence in health care professionals burnout | Arnone, R., Cascio, M.I., Parenti, I. [50] | 2019 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 148 | Doctors, nurses, and other caregivers | LBQ | SSEIT | There is a negative and significant correlation between Burnout and EI | ||

| 17 | Emotional intelligence as a moderator in the stress–burnout relationship: a questionnaire study on nurses | Görgens-Ekermans, G., Brand, T. [51] | 2012 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | 122 | Nurses | MBI | The Swinburne University Emotional Intelligence Test | Consistent inverse relationships between emotional control and management as dimensions of EI, and stress and burnout emerged. A differential effect of high vs. low EI on the stress–burnout relationship was evident. | Workload and the work/family interface emerged as significant predictors of burnout | |

| 18 | Emotional Intelligence Buffers the Effects of Negative Emotions on Job Burnout in Nursing | Szczygiel, D. D., Mikolajczak, M. [52] | 2018 | Poland | Cross-sectional | 188 | Nurses | OLBI | NJES | Negative emotions do not always lead to burnout, but that they particularly do for nurses who lack EI. | ||

| 19 | The Role of Emotional Intelligence on Health Care Professionals Occupational Stress and Burnout | Tiwari, S., Bhagat, D. [53] | 2020 | India | Cross-sectional | 388 | Nurses and Doctors | OLBI | Emotional Quotient Test | The dimensions of EI, emotional sensitivity, emotional maturity, and emotional competency have been reported to significantly predict the all the seven dimensions of occupational stress and the dimensions of burnout and the order and strength of the predictors differ across the two groups of healthcare professionals. | A positive relationship was found between age, working experience, and stress, with younger healthcare professionals and those with a shorter length of service experiencing more stress | EI levels increased with the age and experience of the respondents on emotional intelligence |

| 20 | The Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Job Stress on Burnout: A Structural Equation Model among Hospital Nurses | Samaei, S.E., Khosravi, Y., Heravizadeh, O., Ahangar, H. G., Pourshariati, F., Amrollahi, M. [54] | 2017 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 300 | Nurses | MBI-HSS | The Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire of Cyber or sharing-EI | There was meaningful relationship between EI and job stress with nurses’ occupational burnout. The EI was effective on job stress | A significant difference was found in correlation with income- the higher the income with increasing EI levels | |

| 21 | Evaluating and Exploring Variations in Surgical Resident Emotional Intelligence and Burnout | Beierle, S.P., Kirkpatrick, B.A., Heidel, R.E., Russ, A., Ramshaw, B., McCallum, R.S., Lewis, J.M. [55] | 2019 | United States | Longitu-dinal cohort | 86 | Resident doctors | MBI | Scale of Emotional Functioning: Health Service Provider | The data confirm an inverse relationship between EI and burnout | ||

| 22 | The Mediating Role of Emotion Management, Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence in Clinical Nurses Related to Negative Psychology and Burnout | Yu, C., Liu, Z., Zhao, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Lin, A., ... & Wan, H. [56] | 2023 | China | Cross-sectional | 12704 | Nurses | MBI-GS | ETS | EI among nurses could reduce the incidence of burnout | ||

| 23 | Emotional intelligence, perceived stress and burnout among resident doctors: An assessment of the relationship | Swami, M. K., Mathur, D.M., Pushp, B.K. [57] | 2013 | India | Cross-sectional | 56 | Resident doctors | SMBM | TEIQ | There is a significant negative correlation between burnout and trait EI and a positive correlation with perceived stress indicating that burnout is probably influenced by perception of stress and EI. | ||

| 24 | Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction | Weng, H.C., Hung, C.M., Liu, Y.T., Cheng, Y.J., Yen, C.Y., Chang, C.C., Huang, C.K. [58] | 2011 | Taiwan | Observa-tional | 110 | Doctors | MBI | WLEIS | Higher EI was significantly associated with less burnout and higher job satisfaction. In addition, less burnout was not only associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction, but also with higher levels of job satisfaction. | ||

| 25 | Correlation among Perceived Stress, Emotional Intelligence, and Burnout of Resident Doctors in a Medical College of West Bengal | Mitra, S., Sarkar, A.P., Haldar, D., Saren, A.B., Lo, S., Sarkar, G.N. [59] | 2018 | India | Cross-sectional | 63 | Resident doctors | SMBM | TEIQ | Burnout had a significant positive correlation with perceived stress and in negative correlation with EI-well-being and positive correlation with EI-self-control and sociability. | ||

| 26 | Self-control as mediator between emotional intelligence and burnout among doctors | Jahanzeb, Z., Parveen, S., & Khizar, U. [60] | 2023 | Pakistan | Quantita-tive | 150 | Doctors | MBI | EIS | EI is negatively correlated with burnout. The result showed a significant negative correlation between burn out and self-control. | Burnout appears to be a more female experience, with women reporting it at a higher rate than men | |

| 27 | Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Plastic Surgery Residents: Is There a Relationship? | Bin Dahmash, A.B., Alhadlaq, A. S., Alhujayri, A.K., Alkholaiwi, F., Alosaimi, N.A. [61] | 2019 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 37 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | There is a positive correlation between higher levels of EI and sense of personal achievement, whereas a negative correlation was observed between higher level of EI and EE and DP among the residents in this study. | Significant risk factors for burnout included dissatisfaction with plastic surgery as a career choice, dissatisfaction with income, and dissatisfaction with the role in the operating room | |

| 28 | Emotional Intelligence, Burnout, and Wellbeing Among Residents as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic | Kirkpatrick, H., Wasfie, T., Laykova, A., Barber, K., Hella, J., Vogel, M. [62] | 2022 | United States | Cross-sectional | 81 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | EI continues to partially protect our residents’ burnout and wellbeing. | The COVID-19 pandemic initial surge appeared to negatively alter the protective effect of residents’ emotional intelligence on their burnout and wellbeing in our community hospital. | |

| 29 | Burnout and well-being of medical and surgical residents in relation to emotional intelligence: A 3-year study | Wasfie, T., Kirkpatrick, H., Barber, K., Hella, J., Lange, M., Vogel, M. [63] | 2024 | United States | Longitudinal | 77 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | EI was inversely related to burnout and distress and is related to wellness factors in this community–hospital–based resident study sample. | ||

| 30 | Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Among Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Residents | Sharaf, A. M., Abdulla, I.H., Alnatheer, A.M., Alahmari, A.N., Alwhibi, O.A., Alabduljabbar, Z., ... & Alkholaiwi, F.M. [64] | 2022 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 51 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | This study showed that surgical specialty residents with higher EI levels had a lower risk of burnout | One extra sleeping hour is associated with a 0.44-unit increase in the average EI score; the average EI score was 0.52 units higher in residents who exercised than in those who did not | |

| 31 | Longitudinal study of emotional intelligence, well-being, and burnout of surgical and medical residents | Wasfie, T., Kirkpatrick, H., Barber, K., Hella, J. R., Anderson, T., Vogel, M. [65] | 2023 | United States | Longitudinal | 80 | Resident doctors | MBI | TEIQ-SF | EI is associated with well-being and burnout in individual residents |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).