1. Introduction

When work environments are not well organized and managed, they can have adverse consequences for workers that, rather than dignifying them, exhaust and consume their psychological resources [

1]. Burnout thus constitutes an important psychosocial occupational risk in today's society [

1]. It is characterized as an inadequate response to chronic work-related stress that comprises emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [

2]. According to Maslach and Jackson [

2], emotional exhaustion refers to the feeling among workers that the own ability to give to others on a psychological level is diminished as a result of their emotional resources are depleted. Depersonalization consist of the development of negative, cynical attitudes and feelings about one’s clients, or even dehumanized perception of the clients, considering them as deserving of their troubles. Reduced personal accomplishment refers to the tendency to evaluate oneself negatively, particularly with regard to one’s work with clients, feeling unhappy about oneself and dissatisfied with the accomplishments on the job. Although burnout can occur in any profession, healthcare professionals have the highest prevalence of burnout [

3]. Moreover, particularly among physicians, it has more serious implications for patients. It can undermine the medical care they receive, affect decision-making about their health, and cause medical errors that can have serious consequences [

4].

According to the job demands-resources model [5 ,6], burnout occurs when job demands are high and job resources are low. Job demands refer to a job's aspects (physical, psychological, or organizational) that require physical or mental effort, and incur costs for workers [

6]. Job resources refer to the job aspects (physical, psychological, or organizational) that help reduce job demands and costs, achieve professional goals, or promote workers’ personal development [

6]. In terms of job demands, certain sociodemographic and organizational variables can be risk factors for burnout in physicians, such as being a woman [

7], being younger than 40 years, having fewer than 10 years of professional experience, working shifts, and working a greater number of hours [8-12]. Furthermore, despite the limited literature, scholars are also referring to psychosocial variables such as work-family conflict [9, 13], psychological inflexibility [

14], and loneliness [

15]. Meanwhile, regarding job resources, monthly income [

9], greater professional experience, and social support [12, 15] are related to less burnout among physicians.

Once burnout develops, it has important consequences for the quality of life and health [

16]. Burnout can be related to mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and stress [17, 18]. It also results in poor attention, an inability to concentrate, difficulty retaining information, recurring headaches, lack of sleep, feelings of fatigue, insecurity, and helplessness, and lower work performance [

19].

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical personnel have been exposed to considerable psychological pressure and excessive workload, which dramatically increased the prevalence of burnout among them [

20]. In Latin America, where healthcare systems do not have as many resources, various studies [e.g., 21-23] report that a third or more than half of physicians experienced burnout at some point during the pandemic. This, in turn, negatively impacted psychosocial health, resulting in distress and emotional overload [

24]. Furthermore, it was associated with job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, and physician desertion [25, 26]. Therefore, to improve healthcare system policies, the need to understand the predictors of burnout in these medical professionals and the consequence for their mental health is more evident than ever.

However, extant research has some limitations. Most studies are conducted in North America or Europe [e.g., 10, 11, 13-15, 27]. These studies use convenience samples [8, 9, 11, 15, 27], small sample sizes [11, 15, 27], and low response rates [9, 13, 15, 27]. Only two studies [28, 29] have been conducted in Ecuador, despite it being an emerging country with the eighth largest economy in Latin America [

30] and a growing healthcare system with 23.2 physicians for every 10,000 inhabitants [

31]. Among these studies, only Ramírez et al.'s [

28] work was conducted at a large-scale national level. However, the authors evaluated physicians and nurses and did not present disaggregated results for each profession; therefore, the prevalence and correlates of burnout in physicians remain unknown. Meanwhile, Vinueza-Veloz [

29] used a non-probabilistic sampling method, had a small sample, and did not include professionals working in the private health system. Moreover, the author only analyzed sex, age, profession (physician versus nurse), and level of care as potential correlates, and did not consider other relevant sociodemographic, work-related, or psychological variables. To the best of our knowledge, none of these studies focused solely on medical professionals or evaluated the psychological consequences of burnout. Thus, the national-level prevalence of burnout, factors associated with burnout, and variables related to mental health among Ecuadorian physicians are unknown.

Addressing these gaps, this study sought to determine the prevalence of burnout, its correlates, and its consequences on the mental health of physicians in Ecuador.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample comprised 1977 physicians from Ecuador, a South American country with an area of 256,370 km

2 and 16,938,986 inhabitants [

32]. The sample included first- (performed promotional, preventive, and palliative care functions), second- (performed specialized outpatient functions that required hospitalization), and third-level physicians (performed specialized outpatient and hospital activities). Participants were recruited from 79 public and private hospital centers in the capitals of the country's 24 provinces from April to August 2022 using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling method. The first stage was based on territorial organization and included all provincial capitals. These capitals are distributed across coastal, highland, Amazonian, and insular regions, and have varying population densities ranging from sparsely populated and more rural areas (e.g., Puerto Baquerizo Moreno: 7,290 inhabitants, population density of 3 inhabitants per km²) to more densely populated and urban areas (e.g., Guayaquil: 2,650,288 inhabitants, population density of 324 inhabitants per km²) [

32]. Thus, we could capture wide heterogeneity in the study variables.

In the second stage, 138 health centers of the Ecuadorian Health System were randomly selected in these provincial capitals, with proportional allocation according to the percentage of existing health centers in the different capitals. Specifically, according to data from the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador [

33], approximately 48% of health centers are concentrated in the most densely populated regions, 41% in intermediate population density regions, and 11% in low population density regions. Furthermore, to ensure the representativeness of the different types of health centers, the list of centers in each province was proportionally stratified by type of center (ambulatory health centers, basic and general hospitals, and specialization hospitals) and funding (public or private) through random sampling. The proportions were 88.6% public ambulatory centers, 10% public general hospitals, and 1.4% public specialized hospitals versus 29% private ambulatory centers, 66% private general hospitals, and 5% private specialized hospitals, as stated by the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador [

33]. The sample size was calculated based on an estimated prevalence of burnout of 10%, as determined based on a previous pilot study with a sample of 100 individuals from six health institutions (three private and three public) in the city of Loja (Ecuador) (precision± 2%, alpha error 5%, and expected sample loss = 20%).

Participant inclusion criteria required that subjects had to (a) be a physician, (b) be active, (c) have a minimum of one year of professional experience, and (d) provide informed consent. Those who were on sick leave or absent from their jobs for various reasons (e.g., vacations, stays, and training courses) at the time of the evaluation were excluded.

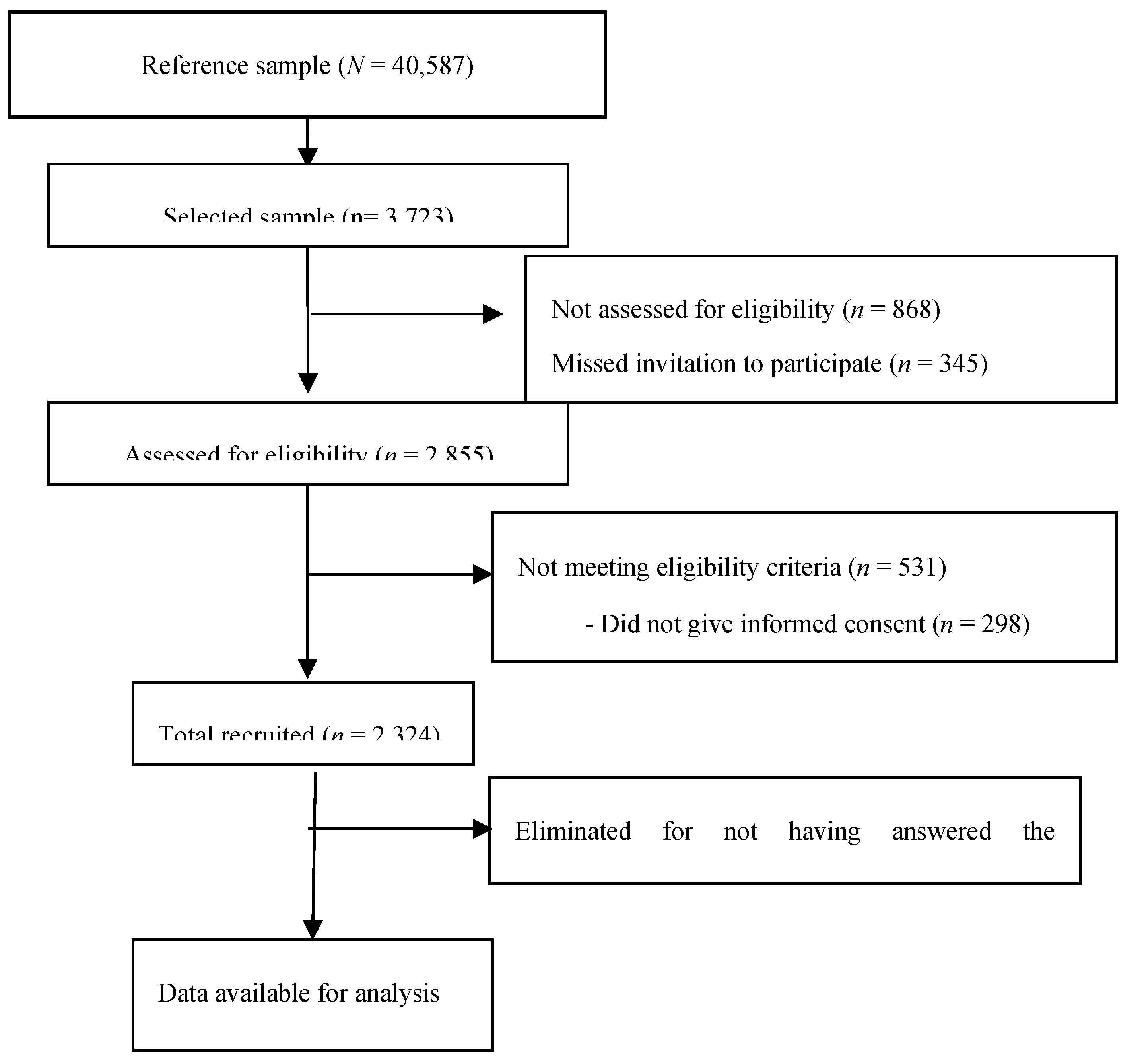

The response rate was 86.0%. Of the total of 3,723 physicians selected, 523 (14.0%) refused to participate because of lack of time, busy schedules, lack of interest, or personal issues. No differences were observed between those who refused to participate and those who did in terms of sociodemographic and job characteristics that we could discern (sex and sector in which they worked). Among those who were assessed, 531 (14.3%) were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria and 348 (9.3%) were eliminated because they did not answer the questionnaires correctly (see

Figure 1). A possible reason for this quantity of erroneously answered questionnaires is that many physicians completed the questionnaires during their working hours, where they have not been able to adequately concentrate due to patients’ attention pressure. The final sample comprised 1,976 physicians (51.8% women, mean age 37.1 years).

To minimize the loss of participants, the guidelines of Hulley et al. for sample recruitment were followed [

34]. These included treating participants with kindness and respect, presenting the study in an attractive way, helping them understand the research in a way that they would want it to be successful, and collecting data in a pleasant manner and as least invasively as possible.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Private Technical University of Loja, Ecuador (Cod. CEISH-03-2022). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed. Participation was voluntary, and the participants did not receive any financial or other compensation.

2.2. Instruments

To evaluate participant characteristics, an ad hoc questionnaire was used that included sociodemographic (sex, age, marital status, and area of residence) and work-related variables (sector in which they work, type of contract, appointment, monthly income, professional experience, shifts, daily work hours, whether they treat patients at risk of death, and whether they perceive work-family conflict).

To evaluate burnout, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; [

2]; Spanish version by Seisdedos [

35]) was used. This self-administered instrument comprises 22 items with seven Likert-type response options ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). It has three subscales: Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment. According to the scoring guidelines by Maslach et al. [

2], for the emotional exhaustion subscale, a cutoff point >26 indicated a high-level category, 19–26 indicated a medium level, and <19 indicated a low level. Regarding depersonalization, scores >9 indicated a high level, 6–9 indicated a medium level, and <6 indicated a low level. For personal accomplishment, scores >39 indicated a high level, 34–39 indicated a medium level, and <34 indicated a low level. A participant was considered to exhibit burnout syndrome when they presented high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment [36, 37]. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the subscales was 0.84 for emotional exhaustion, 0.70 for depersonalization, and 0.77 for personal accomplishment.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ – II; Bond et al. [

38]; Ecuadorian version by Paladines-Costa et al. [

39]) was used to evaluate psychological inflexibility. This self-administered instrument comprises seven items with seven Likert-type response options ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). It helps assess the unwillingness to experience unwanted emotions and thoughts, and the inability to be in the present moment and behave in accordance with value-directed actions when experiencing unwanted psychological events. Higher scores indicated higher levels of psychological inflexibility. The Cronbach's alpha for this instrument was 0.92.

To assess perceived loneliness, the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al. [

40]; Spanish version by Trucharte et al. [

41]) was used. This is a brief three-item scale with three Likert-type response options ranging from 1 (almost never) to 3 (often). It evaluates the subjective feeling of unwanted loneliness, which is understood as the perception of having less social support than desired. Higher scores indicated greater loneliness. The Cronbach's alpha for this instrument was 0.82.

To evaluate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS – 21; Lovibond and Lovibond [

42]; Ecuadorian version by Sanmartín et al. [

43]) was used. It is a self-administered instrument made up of 21 items with four Likert-type response options ranging from 0 (not at all applicable to me) to 3 (very applicable to me) with three dimensions: depression, anxiety, and stress. Scores of ≥ 5 on depression, ≥ 3 on anxiety, and ≥ 7 on stress were considered as indicative of their presence [

44]. Overall, the DASS – 21 presented an alpha of 0.97, and the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales presented Cronbach's alphas of 0.91, 0.91, and 0.90, respectively.

2.3. Procedure

A research protocol was developed to standardize the evaluation procedure, detailing the study objectives, design, and setting: participants (target population, accessible population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sampling, and recruitment), measures (predictor and outcome variables), bias (non-response, recall bias, and selection bias), data analysis strategy, quality control, data management, schedule, and ethical issues.

Because two of the evaluation instruments (MBI and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale) have been previously validated in Spain but not in Ecuador, cultural adaptations were made to use them in a similar language (Spanish) but in another country (Ecuador) [

45] according to the International Test Commission Guidelines [

46]. Two researchers (native Ecuadorian Hispanophones familiar with Castilian Spanish) reviewed the battery of instruments, including instructions, items, and response options. The researchers identified terms unfamiliar to the Ecuadorian population and reworded them to Ecuadorian terms in an independent and parallel manner. Subsequently, an expert committee (comprising three experts in linguistics, and two researchers from Spanish and Ecuadorian cultures) evaluated the semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence of the two versions of each instrument (Castilian and Ecuadorian), and resolved any flaws. The adaptations for these terms were made to retain referential meaning by referring to the same entities, maintaining the pragmatic meaning, and staying close to the lexical and structural features of the source text. The modified versions were reevaluated by the committee. The process was repeated until the committee reached a consensus on the equivalence of the two versions, and the pre-final version was determined. These versions were tested with Ecuadorian professionals and the results of these probes were reviewed by the expert committee, who made the final modifications and signed off the final versions.

Subsequently, a pilot study was conducted to analyze the feasibility with a sample of 100 individuals from six health institutions (three private and three public) in the city of Loja (Ecuador) with characteristics similar to those of those who participated in the study.

The project was disseminated to psychology graduates nationwide from the administrative offices in charge of psychology degrees at the Private Technical University of Loja. The requirements were verified, acceptance was notified, and the training was conducted via Zoom by the members of the research project for 20 hours. Subsequently, a letter was sent to 79 health institutions in the 24 provinces presenting the objectives of the study and inviting them to participate. The collaboration of the directors of the institutions was sought through personal interviews to inform them of the research protocol and schedule dates for instrument collection. The application of the battery of evaluation instruments was online through the ArcGIS platform. Participants were informed of the nature, objectives, risks, and benefits of the study. Confidentiality was guaranteed, and their concerns were answered. After obtaining informed consent, they accessed the battery of instruments to complete the evaluation. The average evaluation duration was 30-35 minutes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical Package for Windows (version 26). For statistical or clinical reasons, some study variables were recoded. Burnout syndrome were dichotomized as absent (0) or present (1), in order to estimate the prevalence of burnout, which may be more practical to guide institutional policy, and facilitate comparisons with previous studies that estimated overall burnout prevalence [

47]. Other variables were also dichotomized: age (≤ 37 years, >37 years), marital status (without/with partner), monthly income (<

$2,000, ≥

$2,000), professional experience (≤ 10 years, >10 years), shifts (no shifts, shifts), daily working hours (≤8 h, >8 h), patients at risk of death (no, yes), work-family conflict (no, yes), psychological inflexibility (≤ 16.6, >16.6), perceived loneliness (≤ 5.1, > 5.1), depression (no, yes), anxiety (no, yes) and stress (no, yes). To enrich the findings with a more nuanced representation of burnout that captures its complexity, we followed the recommendations of Dyrbye et al. [

48]. We reported the categorized results separately using established definitions of low, average, and high cut-off scores for each domain based on scoring guidelines by Maslach et al. [

2].

The means, standard deviations, and frequencies were calculated to analyze the distribution of the sociodemographic, organizational, and psychological variables of the sample, and prevalence of burnout syndrome and its subscales (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment).

We used a modified Poisson regression with robust variance to calculate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals to identify factors associated with burnout syndrome and each subscale. Similarly, modified Poisson regression analyses were performed to analyze the risk of suffering symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in physicians with and without burnout, and each of its subscales. We used this model because the odds ratio estimated using logistic regression from a cross-sectional study may significantly overestimate the relative risk when the outcome is common [

49]. All regression analyses were performed unadjusted and adjusted simultaneously for variables that in previous bivariate analyses reached p-values < .25, following Grant et al. [

50], in addition to theoretical and clinical reasons for including the variables in the model.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Women accounted for 51.8% of participants, with a mean age of 37.1 years (SD = 9.4). The majority of the participants did not have a partner (52.1%), lived in an urban area (84.7%), worked in the public sector (62.7%), had temporary contracts (56.1%), worked full-time (83.8%), and had incomes of less than

$2,000 per month (60.9%). They had an average of 9.6 years (SD = 8.4) of work experience, and 59.4% worked shifts for an average of 10.5 hours per day (SD = 5.4). A total of 85.6% cared for patients at risk of death, and 66.7% experienced work-family conflict. The mean scores for psychological inflexibility and perceived loneliness were 16.6 (SD = 9.8) and 5.1 (SD = 2.3), respectively (

Table 1).

3.2. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome

Physicians had a mean burnout score of 61.8 (SD] = 15.5). Specifically, the average score was 18.7 (SD = 11.7) on the emotional exhaustion subscale, 6.0 (SD = 5.9) for depersonalization, and 37.2 (SD = 9.7) for personal accomplishment.

Notably, 9.0% (n = 177) of physicians presented burnout syndrome (high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment). Specifically, 25.3% (n = 500) had high emotional exhaustion, 23.8% (n = 470) had high depersonalization, and 30.3% (n = 598) had low personal fulfillment (

Table 2).

3.3. Factors Associated with Burnout

As

Table 3 shows, the RR of having burnout syndrome were significantly lower for women (

p = .002, adjusted RR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.50-0.85), and significantly higher for those working in shifts (

p = .001, adjusted RR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.25-2.40), more than eight hours a day (

p = .009, adjusted RR = 1.44, 95% CI 1.10-1.91), experiencing work-family conflict (

p = .007, adjusted RR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.16-2.47), and exhibiting psychological inflexibility (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.06-1.09) and perceived loneliness (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.10, 95% CI 1.04-1.17). No significant differences were observed between professionals with and without burnout syndrome in relation to the other variables.

Next, as shown in

Table 4 for the burnout syndrome subscales, the RR of suffering emotional exhaustion were significantly higher for physicians who work full time (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.00-1.53), more than eight hours a day (

p = .038, adjusted RR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.01-1.34), have work-family conflict (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.53-2.31), and exhibit psychological inflexibility (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.05-1.06) and perceived loneliness (

p = .010, adjusted RR = 1.04, 95% CI 1.01-1.08). The risk of suffering from depersonalization were significantly lower for women (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.65-0.88), and significantly higher for those who work shifts (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.33-1.90), have work-family conflict (

p = .015, adjusted RR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.05-1.52), and exhibit psychological inflexibility (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.04-1.06) and perceived loneliness (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.05-1.13). Finally, the risk of feeling low personal accomplishment was significantly lower for women (

p = .023, adjusted RR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.76-0.98) and those who have patients at risk of death (

p = .005, adjusted RR= 0.76, 95% CI 0.62-0.92). Meanwhile, it was significantly higher for physicians who worked full time (

p = .042, adjusted RR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.01-1.48), worked shifts (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.40-1.91), and exhibited psychological inflexibility (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.04, 95% CI 1.03-1.04) and perceived loneliness (

p = .001, adjusted RR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.02-1.09). No significant differences were observed in the remaining variables.

3.4. Mental Health Symptoms in Physicians with and Without Burnout

As shown in

Table 5, experiencing burnout significantly increased the risk of experiencing symptoms of depression (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.17-1.35) and stress (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.14-1.31).

Specifically, as

Table 6 shows, having high depersonalization and low personal accomplishment significantly increased the risk of suffering depression (

p = .005, adjusted RR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.04-1.26; and

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.23-1.48, respectively). Experiencing high emotional exhaustion and low personal accomplishment significantly increased the risk of suffering anxiety (

p = .001, adjusted RR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.06-1.23; and

p = .006, adjusted RR = 1.11, 95% CI 1.03-1.20, respectively). Finally, having high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization significantly increased the risk of suffering from stress (

p < .001, adjusted RR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.20-1.45; and

p = .015, adjusted RR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.02-1.23, respectively).

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the prevalence of burnout among physicians in Ecuador at the national level, associated factors associated with burnout, and mental health symptoms. We found that 9.0% of physicians presented burnout syndrome. This finding falls in the range of 2.6% and 11.8% reported by a literature review of studies that used the same definition of burnout as in this study [

47]. These figures are concerning, considering that our sample only included professionals who were working at the time of the study. In addition, one must consider the impact of burnout on the quality of care for patients [

4], which can reduce care and suboptimal health outcomes for patients. Regarding burnout subscales, 25.3% of physicians experienced high emotional exhaustion, 23.8% experienced high depersonalization, and 30.3% had low personal accomplishment, indicating a high prevalence of subclinical burnout symptoms. These findings are consistent with those found in the aforementioned review [

47], where the prevalence was between 9.6% and 53.4% for emotional exhaustion, between 11.0% and 47.7% for depersonalization, and between 11.1% and 62.2% for personal accomplishment.

Next, physicians who worked in shifts, worked more than eight hours a day, had work-family conflict, and presented psychological inflexibility and perceived loneliness had a greater risk of suffering burnout, while women exhibited a lower risk. Regarding the burnout subscales, the risk of exhibiting high emotional exhaustion was higher for those who were working full-time, working more than eight hours a day, had work-family conflicts, and exhibited psychological inflexibility and perceived loneliness. Next, those who worked in shifts, had work-family conflict, psychological inflexibility, and perceived loneliness were at higher risk of suffering from high depersonalization. Again, women exhibited lower risk. The risk of presenting low personal accomplishment was higher for those who were working full-time, in shifts, presenting psychological inflexibility, and perceived loneliness, and lower for those who were women and caring for patients at risk of death.

The British Medical Associated presents evidence consistent with our finding that working full-time, with shifts, and long hours (including on-call hours of 24 hours or more) increased the risk of burnout for physicians [

51]. A possible explanation is that working under unfavorable conditions produces exhaustion, and compromises the rest, leisure, and sleep of professionals. Specifically, shifts and daily long working hours produce sleep deprivation, and push the physiological regulation of the circadian rhythm itself as well as emotional and cognitive balance to their limit [

52]. Further, similar to our work, studies find that work-family conflict increases the risk of suffering burnout, high emotional exhaustion, and high depersonalization [9, 13]. This can be explained by the increase in the environmental demands for the professional, and the resulting physical and emotional overload when they cannot reconcile, or find a balance between their personal life and professional demands. Psychological inflexibility increases the risk of burnout, high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. This is consistent Jokic-Begic et al.'s [

14] findings in mental health professionals. Specifically, the authors found that greater psychological inflexibility was related to greater emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and less personal accomplishment. A possible explanation is that the lack of skills in controlling one's own unwanted emotions and thoughts is associated with worse psychological functioning during difficult times. Next, our finding that perceived loneliness is associated with a higher risk of burnout, high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment is consistent with Rogers et al. [

15]. The authors found that loneliness was positively and directly associated with greater burnout. Possible explanations include: 1) the almost exclusive dedication to a professional career in medicine, which leaves little time to cultivate personal relationships, 2) high demands and climate of competitiveness from the stage of academic training to obtain the best grades, and, thus qualify for the desired specialization; and 3) strict hierarchy among healthcare workers, resulting in relationships lacking mutual support in the workplace. Thus, interpersonal relationships between healthcare colleagues are hostile, unsafe, and a source of tension [

53].

Furthermore, the finding that being females exhibited a lower risk of burnout is contrary to some studies [

7], although it is consistent with Castañeda and García del Alba [

8]. This may be because women develop a greater capacity to overcome obstacles and adversity. This makes them more resilient, especially for their professional fulfillment. Furthermore, note that the dimensions of burnout in which a negative association was found were high depersonalization and low personal accomplishment. Hence, a possible explanation may be that the women in the sample of Ecuadorian physicians presented greater empathy and vocation for caring, which increased their perception of self-realization in the performance of their profession. Next, the finding that treating patients at the risk of death reduced the risk of low personal accomplishment may be because it involves facing challenging experiences at a professional level, and allows them to experience of great satisfaction when lives are saved.

Meanwhile, exhibiting burnout significantly increased the risk of experiencing depressive and stress symptoms. Specifically, high emotional exhaustion increased the risk of anxiety and stress, high depersonalization increased the risk of depression and stress, and low personal accomplishment increased the risk for depression and anxiety. Similarly, a previous study [

18] found that burnout was associated with depression and anxiety. A possible explanation for this is the hypothesis of burnout as a “loss spiral” or “burnout cascade” [

54]. This hypothesis postulates that the severity of the consequences of burnout is related to its course, which ranges from the loss of empathy to depression or anxiety.

Our findings have important implications for research, health policy, and clinical practice. They reveal that a considerable number of physicians in Ecuador are at the limit of their endurance at work. Work and personal factors related to burnout and mental health problems associated with burnout were detected. These require attention and coordinated action at the individual, organizational, and policy formulation levels. For instance, the work structure characterized by rotating shifts and long hours (including shifts of 24 hours of work or more) should be changed, as it hinders the integration between work and personal life. Instead, a reduction in the working day, stable shifts, and work-life balance measures (especially in more demanding and sensitive periods, such as maternity/paternity, family illness, or caring for dependent family members) should be implemented. Additionally, the work culture based on competitiveness needs to be reviewed. Instead, efforts should be undertaken to promote teamwork and develop support networks in the work environment. Meanwhile, given the influence of psychological inflexibility on burnout and the psychological symptoms associated with it, psychological support is needed to preserve the mental health of medical personnel, including training in psychological techniques that help them cope with negative emotions and thoughts. Programs that create a people-centered work culture can help balance positive and negative performance, and enable physicians to thrive [

55].

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to establish causality between the variables, deduce the direction of the relationship between burnout and mental health, or determine the influence of possible mediating variables on the analyzed relationships. Longitudinal studies are necessary to prospectively evaluate burnout and mental health problems as well as potential moderating variables. Although the study of correlates provides relevant information about risk factors, future studies should explore pathway analyses to explain how various variables are interrelated. Additionally, this study employed self-report instruments, which could introduce a response bias. Also, because two of the instruments (MBI and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale) have been previously validated in Spain but not in Ecuador, cultural adaptations were made to use them in Ecuador, including rewording to Ecuadorian terms 10 terms in the items that were unfamiliar to the Ecuadorian population. Nonetheless, this is the first study to estimate the prevalence of burnout among physicians in Ecuador at the national level, as well as its association with mental health symptoms. The large sample size, high response rate, and representativeness of the sample at the national level support the generalizability of the results.

5. Conclusions

Our findings have important implications for research, health policy, and clinical practice. They reveal that a considerable number of physicians in Ecuador are at the limit of their endurance at work. Work and personal factors related to burnout and mental health problems associated with burnout were detected. These require attention and coordinated action at the individual, organizational, and policy formulation levels. For instance, the work structure characterized by rotating shifts and long hours (including shifts of 24 hours of work or more) should be changed, as it hinders the integration between work and personal life. Instead, a reduction in the working day, stable shifts, and work-life balance measures (especially in more demanding and sensitive periods, such as maternity/paternity, family illness, or caring for dependent family members) should be implemented. Additionally, the work culture based on competitiveness needs to be reviewed. Instead, efforts should be undertaken to promote teamwork and develop support networks in the work environment. Meanwhile, given the influence of psychological inflexibility on burnout and the psychological symptoms associated with it, psychological support is needed to preserve the mental health of medical personnel, including training in psychological techniques that help them cope with negative emotions and thoughts. Programs that create a people-centered work culture can help balance positive and negative performance, and enable physicians to thrive [

55].

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to establish causality between the variables, deduce the direction of the relationship between burnout and mental health, or determine the influence of possible mediating variables on the analyzed relationships. Longitudinal studies are necessary to prospectively evaluate burnout and mental health problems as well as potential moderating variables. Although the study of correlates provides relevant information about risk factors, future studies should explore pathway analyses to explain how various variables are interrelated. Additionally, this study employed self-report instruments, which could introduce a response bias. Also, because two of the instruments (MBI and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale) have been previously validated in Spain but not in Ecuador, cultural adaptations were made to use them in Ecuador, including rewording to Ecuadorian terms 10 terms in the items that were unfamiliar to the Ecuadorian population. Nonetheless, this is the first study to estimate the prevalence of burnout among physicians in Ecuador at the national level, as well as its association with mental health symptoms. The large sample size, high response rate, and representativeness of the sample at the national level support the generalizability of the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.V, P.O, V.B, M.R.R and M.P.O.; methodology, F.L.V, P.O. V.B, M.R.R, and D.O.; software, M.R.R, and M.P.O.; validation, M.R.R, M.P.O.; formal analysis, P.O.; investigation, F.L.V, P.O, V.B, D.O, and M.R.R.; resources, D.O. M.R.R; data curation, P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.V, P.O. M.R.R. and V.B.; writing—review and editing, F.L.V, P.O. M.R.R. and V.B; visualization, M.R.R.; supervision, F.L.V.; project administration, M.R.R.; funding acquisition, M.R.R, D.O, and M.P.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was financed by the II Call for Knowledge Transfer Observatory projects in 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Private Technical University of Loja, Ecuador (Cod. CEISH-03-2022). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed. All participants were informed about the aim of the study and provided with an opportunity to withdraw at any point.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja for their support in financing and carrying out this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Edú-Valsania, A. Laguía, J.A. Moriano, Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19 (2022) 1780. [CrossRef]

- C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson, Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986.

- C. Maslach, M.P. Leiter, Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15, 2 (2016) 103–111. [CrossRef]

- D.S. Tawfik, J. Profit, T.I. Morgenthaler, D.V. Satele, C.A. Sinsky, L.N. Dyrbye, M.A. Tutty, C.P. West, T.D. Shanafelt, Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 93, 11 (2018) 1571–1580. [CrossRef]

- W.B. Schaufeli, A.B. Baker. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organiz. Behav. 25 (2004), 293-315.

- E. Demerouti, A.B. Bakker, F. Nachreiner, W.B. Schaufeli, The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol., 86 (2001) 499–512.

- T. Hoff, D.R. Lee, Burnout and physician gender: What do we know? Med Care, 59, 8 (2021) 711-720. [CrossRef]

- E. Castañeda, J.E. García de Alba, Prevalence of burnout syndrome and associated variables in Mexican medical specialists. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr., 51 (2022) 41-50. [CrossRef]

- D. Chênevert, S. Kilroy, K. Johnson, P.L. Fournier, The determinants of burnout and professional turnover intentions among Canadian physicians: Application of the job demands-resources model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 1 (2021) 993. [CrossRef]

- D. Mijakoski, A. Atanasovska, D. Bislimovska, H. Brborović, O. Brborović, L. Cvejanov Kezunović, M. Milošević, J. Minov, B. Önal, N. Pranjić, L. Rapas, S. Stoleski, K. Vangelova, R. Žaja, P. Bulat, A. Milovanović, J. Karadžinska-Bislimovska, Associations of burnout with job demands/resources during the pandemic in health workers from Southeast European countries. Front. Psychol. 14 (2023) 1258226. [CrossRef]

- E. Panagopoulou, A. Montgomery, A. Benos, Burnout in internal medicine physicians: Differences between residents and specialists. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 17 (2006) 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Z. Xie, J. Dai., L. Zhang, Y. Huang, B. Chen, Physician burnout and its associated factors: A cross sectional study in Shanghai. J. Occup. Health, 56, 1 (2014) 73-83. [CrossRef]

- L.N. Dyrbye, T.D. Shanafelt, C.M. Balch, D. Satele, J. Sloan, J. Freischlag, Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: A comparison by sex. Arch. Surg, 146, 2 (2011) 211–217.

- N. Jokic-Begic, A.L. Korajlija, D. Begic, Mental health of psychiatrists and physicians of other specialties in early Covid-19 pandemic: Risk and protective factors. Psychiatr. Danub., 32, 3-4 (2020) 536-548. [CrossRef]

- E. Rogers, A.N. Polonijo, R.M. Carpiano, Getting by with a little help from friends and colleagues: Testing how residents' social support networks affect loneliness and burnout. Can Fam Physician 62, 11, (2016) 677–683.

- L.A. Gaston-Hawkins, F.A. Solorio, G.F. Chao, C.R. Green, The Silent Epidemic: Causes and consequences of medical learner burnout. Curr. Psychiatry Rep., 22, 12 (2020), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- K. Ahola, Occupational burnout and health, people and work research, report 81. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 2007.

- A. Yilmaz, Burnout, job satisfaction, and anxiety-depression among family physicians: A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care, 7, 5 (2018) 952–956. [CrossRef]

- A. Bayes, G. Tavella, G. Parker, The biology of burnout: Causes and consequences. World J. Biol. Psychiatry, 22, 9 (2021) 686–698. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Macaron, O.A. Segun-Omosehin, R.H. Matar, A. Beran, H. Nakanishi, C.A. Than, O.A. Abulseoud, A systematic review and meta analysis on burnout in physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A hidden healthcare crisis. Front. Psychiatry, 13 (2023) 1071397. [CrossRef]

- A. Juarez-Garcia, Psychosocial factors and mental health in Mexican women healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saf. Health Work, 13 (2022) 1-2. [CrossRef]

- A. Samaniego, A. Urzúa, M. Buenahora, P. Vera-Villarroel, Sintomatología asociada a trastornos de salud mental en trabajadores sanitarios en Paraguay: efecto COVID-19. [Symptomatology associated with mental health disorders in health care workers in Paraguay: the effect of COVID-19]. Interam. J. Psychol., 54, 1 (2020) 1-19.

- J. Martin-Delgado, R. Poblete, P. Serpa, A. Mula, I. Carrillo, C. Fernández, V. Ripoll, C. Loudet, F. Jorro, E. Garcia Elorrio, M. Guilabert, J.J. Mira, Contributing factors for acute stress in healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador. Sci. Rep., 12, 1, (2022) 1-10. [CrossRef]

- V. Giordano, W. Belangero, A.L. Godoy-Santos, R.E. Pires, J.A. Xicará, P. Labronici, Clinical Decision Rules (CDR) Study Group, The hidden impact of rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in professional, financial, and psychosocial health of Latin American orthopedic trauma surgeons. Injury, 52, 4, (2021) 673–678. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Garcia, T.D. Shanafelt, C.P. West, C.A. Sinsky, M.T. Trockel, L. Nedelec, Y.A. Maldonado, M. Tutty, L.N. Dyrbye, M. Fassiotto, Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw. Open, 3, 8 (2020). e2012762. [CrossRef]

- R. Suñer-Soler, A. Grau-Martín, D. Flichtentrei, M. Prats, F. Braga, S. Font-Mayolas, M.A. Gras, The consequences of burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals in Spain and Spanish speaking Latin American countries. Burn. Res.1, 2 (2014) 82–89. [CrossRef]

- C. Teixeira, O. Ribeiro, A.M. Fonseca, A.S. Carvalho, Burnout in intensive care units – a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: A descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol.13, 1 (2013) 38.

- M.R. Ramírez, P. Otero, V. Blanco, M.P. Ontaneda, O. Díaz, F.L. Vázquez. Prevalence and correlates of burnout in health professionals in Ecuador. Compr Psychiatry, 82, (2018), 73-83. [CrossRef]

- A. Vinueza-Veloz, N. Aldaz-Pachacama, C. Mera-Segovia, E. Tapia-Veloz, M. Vinueza-Veloz, Síndrome de Burnout en personal sanitario ecuatoriano durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. [Burnout Syndrome in Ecuadorian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic]. Corr. Cient. Med. 25, (2021) 2.

- International Monetary Fund. World economic and financial survey. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/index.aspx, Accessed date: 15 October 2023.

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador. Registro estadístico de recursos y actividades de salud – RAS 2020 [Statistical register of health resources and activities - RAS 2020]. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_Sociales/Recursos_Actividades_de_Salud/RAS%1F_2020/Boletín_Técnico_RAS_2020.pdf; 2020, Accessed 15 October 2023.

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador. Resultados del Censo de Ecuador [Results of the Ecuador Census]. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas/ 2023, Accessed 31 July 2024.

- Ministry of Public Health. Plan decenal de Salud 2022-2031 [Ten-year health Plan]. 2022, Accessed 30 July 2024.

- S. B., Hulley, T. B., Newman, S. R., Cummings. Choosing the study subjects: Specification, sampling and recruitment. In: S. B., Hulley, S. R., Cummings, W. R., Browner, D. G., Grady, T. B., Newman, editors. Designing clinical research. 4th edn (2013) p. 23–31. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- N. Seisdedos. MBI: Inventario Burnout de Maslach [MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory]. Madrid: Ediciones TEA; 1997.

- C. Maslach, W.B. Schaufeli, M.P. Leiter, (2001). Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol, 52, 397–422.

- A.J. Ramirez, J. Graham, M.A. Richards, A. Cull, W.M. Gregory. Mental health of hospital consultants: The effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet, 347, (1996) 724–728.

- F. W. Bond, S.C. Hayes, R.A. Baer, K.M. Carpenter, N. Guenole, H.K. Orcutt, T. Waltz, R.D. Zettle, Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 42, (2011) 676–688. [CrossRef]

- B. Paladines-Costa, V. López-Guerra, P. Ruisoto, S. Vaca-Gallegos, & R. Cacho, Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Spanish version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) in Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18, (2021), 2944. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Hughes, L.J. Waite, L.C. Hawkley, J.T. Cacioppo, A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging, 26, (2004) 655-672. [CrossRef]

- A. Trucharte, L. Calderón, E. Cerezo, A. Contreras, V. Peinado & C. Valiente, Three-item loneliness scale: Psychometric properties and normative data of the Spanish version. Curr. Psychol. 42 (2023), 7466-7474. [CrossRef]

- P. Lovibond, S. Lovibond, The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther., 33, 3 (1995), 335–343. [CrossRef]

- R. Sanmartín, R. Suria-Martínez, M.d.L. López-López, M. Vicent, C. Gonzálvez, & J.M. García-Fernández, Validation, factorial invariance, and latent mean differences across sex of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21) in Ecuadorian university sample. Professional Psychol: Res. Practice, 53(4), (2022) 398–406. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Henry, J.R. Crawford. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 44(Pt. 2), (2005) 227–239. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Beaton, C. Bombardier, F. Guillemin, M.B. Ferraz, Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25 (2000) 3186-3191.

- International Test Commission. The ITC guidelines form translating and adapting tests. 2017. https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation.pdf.

- L.S. Rotenstein, M. Torre, M.A. Ramos, R.C. Rosales, C. Guille, S. Sen, S.D.A. Mata. Prevalence of burnout among physicians. A systematic review. JAMA, 320, (2018) 1131-1150. [CrossRef]

- L.N. Dyrbye, C.P. West,. & T.D. Shanafelt. Defining burnout as a dichotomous variable. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 24, 3 (2009) 440. [CrossRef]

- G. Zou. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol., 159, 7 (2004) 702-706. [CrossRef]

- S.W. Grant, G.L. Hickey, S.J. Head, Statistical primer: Multivariable regression considerations and pitfalls. Eur. J. CardioThorac. Surg., 55, 2 (2019) 179-185. [CrossRef]

- British Medical Association. Fatigue and sleep deprivation. The impact of different working patterns on doctors. (2018) British Medical Association.

- G. Rosenbluth, C.P. Landrigan, Sleep, work hours, and medical performance. In F.P. Cappuccio, M.A. Miller, S.W. Lockley, S.M. Rajaratnam (eds). Sleep, health, and society: From aetiology to public health (2018) pp. 198-205. Oxford University Press.

- E., Wainwright, A. Looseley, R. Mouton, M. O’Connor, G. Taylor, T.M. Cook. Stress, burnout, depression and work satisfaction among UK anaesthetic trainees: A qualitative analysis of in-depth participant interviews in the satisfaction and wellbeing in anaesthetic training study. Anaesthesia. 74, 10 (2019) 1240–1251. [CrossRef]

- E.S. Williams, C. Rathert, S.C. Buttigieg, The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: A systematic review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 77, 5 (2020) 371-386. [CrossRef]

- D. Carrieri, K. Mattick, M. Pearson, C. Papoutsi, S. Briscoe, G. Wong, M. Jackson, Optimising strategies to address mental ill-health in doctors and medical students: 'Care Under Pressure' realist review and implementation guidance. BMC Med., 18, (2020) 76. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).