1. Introduction

Burnout is a state of exhaustion caused by prolonged exposure to work-related problems [

1] or sustained involvement in emotionally demanding work environments [

2]. It results from unmanaged chronic stress [

3]. A multistage process, burnout develops gradually, starting with initial work enthusiasm, followed by increasing pressure, conflicts, shifts in values, depression, and finally, the emergence of burnout symptoms [

4].

Without timely intervention, individuals experiencing burnout may exhibit clinical symptoms such as emotional exhaustion, physical fatigue, cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, and functional decline [

5,

6]. In severe cases, burnout can result in depression or anxiety disorders [

5]. These effects are particularly concerning in the medical workplace, where they can diminish nurses’ well-being [

7], weaken the workforce [

8], and lead to significant professional consequences, including decreased patient satisfaction [

9], compromised quality of care [

10] , and increased medical errors [

11].

The absence of a clear, unified definition of burnout syndrome has contributed to variations in its reported prevalence, ranging from approximately 4% to 25% across different regions and countries [

3].

Healthcare workers are at particularly high risk, with burnout prevalence estimated between 10% [

12] and 50% [

13]. This heightened risk stems from the intense stress of close contact with patients and their families. These findings underscore the significant threat that burnout poses to the mental health of healthcare professionals.

Healthcare workers in Asia often report long working hours. Overtime is common among hospital physicians in Taiwan [

14], while over 10% of nurses in Korea work more than 52 hours per week [

15]. Similarly, nurses in Taiwan average over 50 hours of work per week [

16].

Research has consistently shown that overtime or extended working hours harm physical and mental health, resulting in irritability, fatigue, anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms [

17], reduced sleep duration, and poorer subjective sleep quality [

18]. Extended working hours also increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases [

19]. In medical settings, these health impacts can depress the quality of care [

20] and increase the incidence of healthcare-associated infections [

21].

Additionally, overtime work is strongly associated with higher staff turnover intentions [

22] and increased work-to-family conflict [

23]. These findings highlight the serious harm caused by overtime in medical institutions and underscore the need for urgent attention.

In summary, burnout and overtime significantly impact medical staff’s physical and mental health. Interestingly, the two conditions share many overlapping symptoms. This raises a critical question: Is there a close link between overtime and occupational burnout?

Research on burnout has primarily conducted cross-sectional studies, which do not fully capture the long-term effects of risk factors on burnout. Notably, prior studies have indicated that the risk of burnout may accumulate and intensify over time [

24] , which warrants deeper investigation. To fill this gap, adopting a longitudinal approach that enables us to explore the temporal dynamics of burnout development is crucial.

Thus, we propose the following hypotheses for further testing:

H1. The risk of burnout increases over time.

H2. Individuals who experience overtime face a higher burnout risk.

By testing these hypotheses, we aim to clarify whether extended overtime directly affects the risk of occupational burnout. This research may provide valuable insights into the mechanisms linking overtime and burnout, ultimately informing interventions that improve the well-being of medical staff and the quality of healthcare delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

This longitudinal observational study utilized deidentified secondary databases, incorporating four waves of survey questionnaires from 2021 to 2024. The secondary data were initially collected for purposes unrelated to this study, and all identifying information was removed before data access by the research team. The Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, reviewed and approved the study protocol on January 24, 2025 (CSMUH No: CS1-24226). All research procedures adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring confidentiality, anonymity, and proper handling of the secondary data throughout the study. The data were collected from a hospital affiliated with a medical university in Taichung, Taiwan. The questionnaires were distributed via QR code-linked emails to staff employed for over a year. Notably, instead of utilizing a sampling method, the study aimed to include the entire population of eligible staff, ensuring greater representativeness and minimizing potential sampling biases.

All questionnaires included participants’ basic demographic information, living habits, occupational characteristics, and the Copenhagen burnout inventory (CBI). Developed by researchers in Denmark, the CBI is recognized for its exceptionally high internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas reaching 0.85–0.87. It was designed to be both comprehensible and accessible to all individuals [

25]. We used the traditional Chinese version of the CBI [

26] to align with the national context. We ensured its applicability to all participants by adopting the personal burnout (PB) scale from the CBI, a universal tool for measuring fatigue or exhaustion levels regardless of occupational status, including staff who do not face clients [

25]. The six questions for the PB scale are listed in

Supplementary Information Table S1. The response options were “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “seldom,” and “never/rarely,” assigned scores of 100, 75, 50, 25, and 0, respectively. The mean score of the six items was used as an index of the PB level. CBI was not a diagnostic criterion for burnout; therefore, we defined the upper quartile of the mean PB score from the first wave in 2021 as the criterion for determining high PB level (HPBL) in subsequent waves from 2022 to 2024.

The response options for sex were “female” and “male,” and participants reported their age in years. Marital status was categorized as “married” or “other.” Participants’ height and weight were measured, and BMI was reclassified into four groups per the criteria established by the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan: underweight (BMI < 18.5), healthy weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0), overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI < 27.0), and obese (BMI ≥ 27.0). The response options for the highest education degree were “PhD,” “Master,” “Bachelor,” and “other.” For overtime, the response options were “Rarely overtime,” “Monthly overtime less than 45 hours,” “Monthly overtime between 45 and 80 hours,” and “Monthly overtime over 80 hours.” In terms of shift work, the questionnaire included the options “irregular,” “regular,” “night,” and “day” shift work. The study also assessed participants’ average sleeping time during work periods, with response options of “less than 5 hours,” “5–6 hours,” “6–7 hours,” “7–8 hours,” and “over 8 hours.” Whether participants engaged in leisure activities with family and friends (LAFF) during vacations was also surveyed, with the response options of “Never,” “Rarely,” “Occasionally,” “Often,” and “Always.” Participants were asked to select from the chronic diseases listed in the questionnaire; having one or more was categorized as “suffering from chronic disease.” The response options for professional fields were nurses, administrative staff, physicians (including attending physicians, residents, and nurse practitioners), and technical staff.

The questionnaire responses in 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 were 1,615, 1,694, 1,608, and 1,221, respectively. We excluded participants who sustained HPBL in the first survey or only completed the survey once. All participants were classified by one of the following three outcomes during follow-up: meeting the HPBL criteria, not meeting the HPBL criteria, or being lost to follow-up. Participants who met the HPBL criteria (event = 1) would no longer contribute additional records, and the total duration of observation (in years) would be calculated up to that point. Regarding loss to follow-up, we would adopt the “carrying forward the last observation” [

27] method. Thus, the last recorded data and condition before the loss to follow-up would be considered as “not meeting HPBL” (alive; event = 0) and serve as the duration’s endpoint. For participants still “alive” at the end of the study period (2024), the “event” would also be set to zero and would serve as the endpoint for the duration of the study.

We examined the impact of time on burnout by employing survival analysis [

28] to evaluate the occurrence of HPBL during the observation period among the cohort. The Kaplan–Meier method [

29] was used to graphically represent endpoint occurrences over time and estimate the survival probability of HPBL in the population under investigation [

30]. Survival analyses typically have greater statistical power to detect significant treatment or exposure effects than binary logistic regression, as they take into account the time to an event [

29]. Additionally, we will perform a stratified analysis of overtime work to examine differences in the survival probability of HPBL using the Log-rank test. The Cox regression model [

31,

32] was utilized to explore the effect of overtime on survival probability while considering adjusted variables.

Hypothesis 1 (H1) and Hypothesis 2 (H2): were tested in four steps:

Step 1: Descriptive statistics summarized the participants’ basic demographic characteristics and surveyed variables.

Step 2: Survival analysis examined whether the risk of burnout increased over time (H1).

Step 3: Stratified survival analysis evaluated whether experiencing overtime contributed to a higher risk of worsening burnout over time (H2).

Step 4: Multiple Cox regression analysis assessed whether overtime is an independent risk factor for burnout.

The present study used SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for data analysis, and statistical significance was set at P <0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the number of individuals who completed the questionnaires between 2021 and 2024 and the PB mean scores’ quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3). The Cronbach’s alpha for the PB scale was 0.92, 0.93, 0.94, and 0.93 for 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024, respectively. A PB score above 45.83 (Q3) was defined as HPBL, according to the upper quartile threshold in 2021. The proportions of individuals classified as HPBL were 489 (30.28%) in 2021, 564 (33.29%) in 2022, 591 (36.75%) in 2023, and 397 (32.51%) in 2024. Statistical analysis showed significant variation in the mean PB scores across the years (P = 0.008), with the highest mean recorded in 2023.

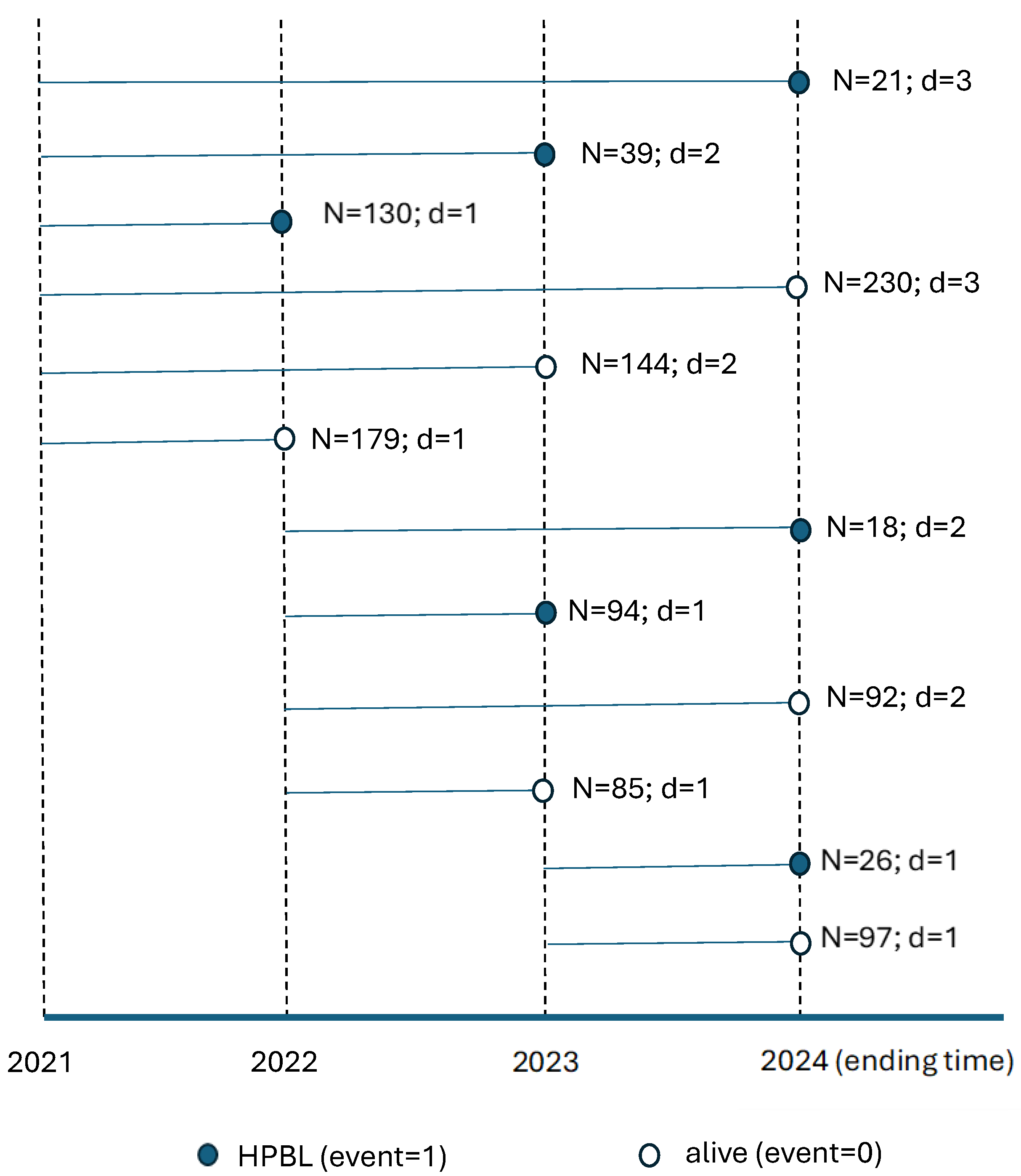

Figure 1 illustrates the observation process, excluding individuals who either met the HPBL criteria for the first time or were lost to follow-up by the second year. The final observation cohorts comprised 743 participants in 2021, 289 in 2022, and 123 in 2023.

Among the observation cohorts from 2021, 21 individuals met the HPBL criteria in 2022, 39 in 2023, and 130 in 2024. Additionally, 179 individuals in 2022 and 144 in 2023 did not meet the HPBL criteria but were subsequently lost to observation the following year. In 2024, the observation of 230 individuals who did not meet the HPBL criteria was concluded.

Among the observation cohorts from 2022, 94 individuals met the HPBL criteria in 2023 and 18 in 2024. Additionally, 85 individuals did not meet the HPBL criteria in 2023 but were subsequently lost to observation the following year. In 2024, the observation of 92 individuals who did not meet the HPBL criteria was concluded.

In 2024, 26 individuals from the 2023 observation cohorts met the HPBL criteria, whereas 97 individuals did not in the same year.

Table 2 summarizes the demographic variables and observation results for the 1,155 participants who completed the observation. A total of 358 (48.18%) individuals in 2021 and 85 (29.41%) in 2022 were lost to follow-up. The participant mean age of those who continued observation was 40.66 ± 10.31 years in 2021, 37.07 ± 10.17 years in 2022, and 36.15 ± 10.57 years in 2023. The participants were predominantly female, accounting for 74.80%–85.81% of the cohorts, among whom the proportion that met the HPBL criteria (event = 1) ranged from 21.14% to 38.75%.

The mean duration of observation was 1.92 ± 0.87 years in 2021, 1.38 ± 0.49 years in 2022, and 1.21 ± 0.41 years in 2023. The number of participants holding a Master’s or PhD degree was 144 (19.38%) in 2021, 51 (17.65%) in 2022, and 26 (21.14%) in 2023. Regarding professional fields, the number of physicians and nurses was 59 (7.94%) and 235 (31.63%) in 2021, 30 (10.38%) and 141 (48.79%) in 2022, and 14 (11.38%) and 37 (30.08%) in 2023, respectively.

The symbols “+/−” represent the state change between the last and previous observations. Specifically:

“Getting married+” indicates that the participant reported being newly married in the most recent observation survey.

“LAFF+” represents an increase in the frequency of leisure activities with family and friends (LAFF) compared to the previous survey.

“Overtime+” indicates an increased frequency of overtime compared to the previous survey.

“Sleep time-“ represents a decrease in sleep time compared to the previous survey.

“Shift work+” indicates transitioning from a regular day/night schedule to shift work.

“OW/OB+” signifies that the participant’s body weight changed from being underweight or a healthy weight to being overweight or obese in the final observation.

“Chronic diseases+” indicates that the participant began to suffer from at least one chronic disease in the final observation.

Among the participants in 2021, 2022, and 2023, 20 (2.69%), 8 (2.77%), and 5 (4.07%) individuals, respectively, reported being newly married. A relative increase in the frequency of leisure activities with family and friends (LAFF) over the previous survey was observed in 149 (20.50%), 56 (19.38%), and 31 (25.20%) participants, respectively. Regarding overtime status, 84 (11.31%), 48 (16.61%), and 20 (16.26%) individuals reported transitioning from rarely working overtime to working over 45 hours in overtime monthly. Furthermore, 191 (25.71%), 55 (19.03%), and 33 (26.83%) participants reported sleeping less during their working periods.

In terms of work schedules, 35 (4.71%), 23 (7.96%), and 9 (7.32%) individuals reported shifting from day/night work to shift work. Twenty-two (2.96%), 13 (4.50%), and 4 (3.25%) participants increased from being underweight/healthy weight to overweight/obesity. Additionally, 65 (8.75%), 36 (12.46%), and 9 (7.32%) participants recently reported being diagnosed with at least one chronic disease.

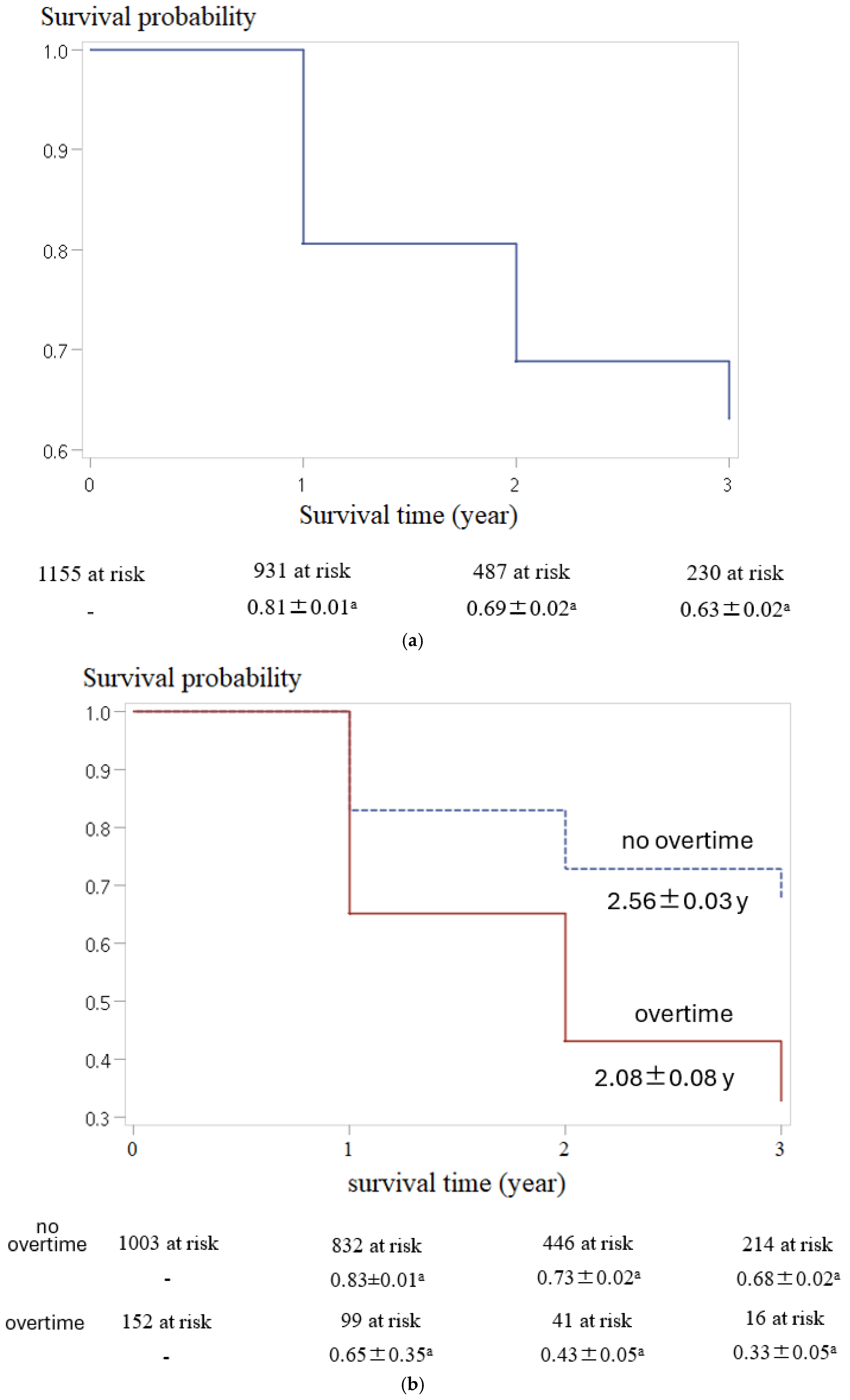

Figure 2a illustrates the survival probability over time of the participants with HPBL, with a mean survival time estimated at 2.50 ± 0.03 years. After one year, the survival probability was 0.81 ± 0.01, with 931 participants remaining at risk. By the second year, the survival probability decreased to 0.69 ± 0.02 (487 participants at risk), and by the 3rd year, it further declined to 0.63 ± 0.02 (230 participants at risk). All survival probabilities were calculated using Kaplan–Meier estimates. Thus, Hypothesis H1 about the risk of burnout increasing over time is confirmed.

Figure 2b demonstrates that individuals who work overtime have significantly shorter survival times for HPBL and higher probabilities of HPBL progressing than those who do not work overtime. The mean survival time was 2.56 ± 0.03 years for individuals who did not work overtime, compared to 2.08 ± 0.08 years for those who did (Log-rank test, P <.0001). The probability of survival was 0.83 and 0.65 at year 1, 0.74 and 0.43 at year 2, and 0.68 and 0.33 at year 3 for the no-overtime and overtime groups, respectively (Log-rank test, P <.0001). These results provide strong evidence in support of Hypothesis H

2 that individuals who work overtime are at a significantly higher risk of burnout that worsens over time.

M

0 in

Table 3 identified overtime (+), age, the female gender, being a physician or nurse, reduced sleep time (−), and overweight/obesity (OW/OB, +) as potential confounders of HPBL. These variables were incorporated as adjusted covariates in the Cox regression model. The multiple Cox regression model (M1) demonstrated that overtime (+), the female gender, being a physician or nurse, reduced sleep time (−), and OW/OB (+) were independent risk factors for HPBL. Specifically, individuals who worked overtime in the past year had a 113% higher risk of experiencing HPBL than those who rarely worked overtime (HR = 2.13, P <.001); thus, Hypothesis H

2 is verified.

Notably, female employees had a 49% higher risk of HPBL than their male counterparts (HR = 1.49, P = 0.025). Furthermore, physicians and nurses faced significantly higher risks of HPBL than other healthcare workers: physicians were at a 79% higher risk (HR = 1.79, P = 0.004) and nurses at a 57% higher risk (HR = 1.57, P = 0.001).

Additionally, individuals who reduced their daily sleep duration compared to the previous year faced a 29% higher risk of developing HPBL (HR = 1.29, P = 0.037). Importantly, those whose body weight shifted from underweight or healthy weight to overweight or obese in the past year showed a 72% higher risk of developing HPBL (HR = 1.72, P = 0.035).

4. Discussion

In response to the threat of COVID-19, hospitals across Taiwan adopted various epidemic prevention measures, including daily temperature and health monitoring for all staff, service recipients, and accompanying persons, starting on June 7, 2021. These measures were gradually lifted beginning in May 2023 [

33,

34]. As shown in

Table 1, healthcare workers reported higher levels of PB in 2022 and 2023 than in 2021 and 2024, aligning with the prolonged challenges during the pandemic period of COVID-19.

Our longitudinal observational study of healthcare workers found the risk of PB increases over time (H1) and individuals working overtime face a higher risk of worsening burnout than those who do not work overtime (H2). These findings support our proposed hypotheses.

In the multiple Cox regression model, women exhibited a higher risk of burnout than men over time; likewise, reduced sleep time and being overweight or obese were also significantly associated with a greater risk of burnout.

Burnout’s Progressive Onset

Figure 2a illustrates that the survival probability of HPBL decreases over time, reflecting a significant and progressive worsening of burnout among individuals. This trend aligns with the progressive stages of burnout development [

4], which is confirmed by previous studies. For example, research on burnout among frontline physicians in the US during the pandemic demonstrated that fatigue and frustration progressively worsened burnout [

24]. Similarly, female residents experienced increased emotional exhaustion between their second and third years of residency [

35].

Why does the risk of burnout increase over time? Burnout is widely recognized as a multistage process that typically begins with work-related stress [

4]. In the initial phase, stress can diminish enthusiasm and lead to stagnation. Prolonged exposure to stress results in frustration, gradually depleting energy and enthusiasm for work. If left unaddressed, this progression may culminate in significant physical and emotional challenges that require professional intervention [

3].

These findings show the gradual nature of burnout development and underscore a critical window for intervention. Early identification of individuals at risk and targeted strategies during burnout’s early stages play pivotal roles in mitigating its progression and reducing its long-term consequences.

4.1. Risk Factors of Burnout

We have established that burnout worsens over time. Before examining the impact of overtime on burnout, we must first identify and control for potential confounders. One notable factor is gender. The data presented in

Table 3 indicate that female employees had a significantly higher risk of HPBL than their male peers during the observation period (HR = 1.49, p = 0.025). This finding is consistent with prior research, which has consistently reported gender-related disparities in HPBL risk. Understanding this disparity is critical because it may reflect underlying differences in work–life balance pressures, societal expectations, or coping mechanisms. These gender-specific factors should be considered in future interventions aimed at mitigating burnout. A cross-sectional survey of members of the American College of Surgeons demonstrated that more women than men surgeons suffered from burnout due to work–home conflicts [

36]. Likewise, a longitudinal study found that female residents experienced emotional exhaustion more easily than male residents [

35]. These reasons may stem from slower promotions, lower salaries, fewer resources, and inequality, resulting in pressure related to decisions on when to have children, as well as conflict between fulfilling roles as a spouse and parent while pursuing a career [

37,

38]. Addressing these gender-specific issues is critical for designing interventions that effectively mitigate burnout and promote equity in the workplace.

The prevalence of burnout among physicians in the US is approximately 50%, twice as high as that of the general working population [

39]. Similarly, the prevalence of burnout among nurses ranges from 10.51% to 33% worldwide, depending on regional and methodological differences [

12,

40]. Both physicians and nurses are considered to be high-risk populations for burnout.

After adjusting for confounding variables (

Table 3), physicians (HR = 1.79, p = 0.004) and nurses (HR = 1.57, p = 0.001) were found to have a significantly higher risk of HPBL than other healthcare workers. This trend indicates that occupational roles influence burnout risk, likely driven by workload, stress, and workplace challenges. Our findings confirm the classification of physicians and nurses as high-risk groups for burnout. Future research should identify and address the specific drivers of burnout within these professions to mitigate its impact and enhance the well-being of healthcare workers.

Sleep duration has been linked with mortality [

41] and is increasingly recognized as a critical factor in burnout. Research studies have consistently identified insufficient sleep, defined as less than 6 hours per night, as a significant risk factor for burnout [

42]. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated that reduced daily sleep duration significantly increased the risk of HPBL (

Table 3, HR = 1.29, P = 0.037) in a multivariate analysis, underscoring the significant association between inadequate sleep and burnout. These results highlight adequate sleep’s critical role in mitigating burnout risk and suggest that interventions targeting sleep hygiene may effectively reduce burnout prevalence among high-risk populations.

Previous cross-sectional studies have shown that higher levels of burnout are linked to increased fat intake [

43] and a greater risk of obesity [

44], suggesting a possible bidirectional relationship between obesity and burnout. Our study’s Cox regression analysis revealed that being overweight and obesity (HR = 1.72, P = 0.035) were independent risk factors for HPBL. This finding aligns with earlier research, indicating that weight management may help reduce the risk of burnout.

Nevertheless, the causal relationship between obesity and burnout remains unclear. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether obesity predisposes individuals to burnout or if burnout contributes to obesity. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing obesity as part of a comprehensive strategy to mitigate burnout, especially in high-risk occupational groups.

4.2. Overtime Effect on Burnout

Overtime work poses a substantial risk to workers’ mental health. A study conducted in Japan found that extended overtime hours were significantly associated with heightened levels of anxiety and depression [

17]. Similarly, involuntary overtime among nurses has been shown to adversely impact mental health and work engagement [

45]. Building on this evidence, several cross-sectional studies have established a correlation between overtime work and burnout [

46,

47]. However, cross-sectional designs limit the ability to establish causal relationships, suggesting the need for longitudinal research to investigate the temporal effects of overtime on burnout.

We adopted survival and Cox regression analyses to address this limitation and explore the relationship between overtime and burnout. These methods provided evidence supporting a causal link between increased overtime work and burnout. Specifically, individuals who reported an increased frequency of working overtime in the past year had significantly shorter survival times and a greater risk of HPBL (

Figure 2b and

Table 3, M1). These findings underscore the critical role of overtime in developing burnout and highlight the necessity for targeted interventions to mitigate this risk, such as workload management and policies to limit excessive overtime.

Finally, we propose a possible explanation for the relationship between overtime work and burnout through the lens of work–family conflict. Overtime work often exacerbates work–family conflict [

48], primarily by impeding psychological detachment from work [

49]. Drawing on the 12-stage model of burnout development [

4], we hypothesize that individuals initially approach work with enthusiasm. As work demands grow, they may begin to neglect their personal needs and relationships, which may escalate unresolved conflicts, shift personal values, and lead to a denial of existing problems, ultimately contributing to burnout.

While this hypothesis provides a theoretical framework for understanding the link between overtime and burnout, additional empirical research is needed to validate these mechanisms. Future interventions could focus on promoting work–life balance and supporting psychological detachment from work, mitigating the effect of overtime work on burnout.

5. Limitation

The study encountered a loss-to-follow-up rate exceeding 20% (

Table 2, 2021: 48.18%; 2022: 29.41%), which may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of our findings, [

50]. A high loss-to-follow-up rate could underrepresent certain population groups and affect the observed trends’ robustness.

While our results indicate increasing burnout over time, the high loss to follow-up rate suggests caution in interpreting these findings. Future studies should aim to improve participant retention through enhanced follow-up strategies.

Our research design investigated whether overtime work increased during two periods. Still, this approach ignored the burnout of those who have worked overtime for many years and cannot determine whether reducing overtime can improve burnout.

Unlike illness or death, burnout is dynamic and may fluctuate between surveys. The 1-year survey interval may have failed to capture transient episodes, potentially overestimating the survival time.

We must emphasize that HPBL is a relatively high value observed within a specific survey population; it is not a clinical diagnostic criterion. Additionally, it may vary across different survey populations. Therefore, to avoid misunderstanding, we should refrain from using terms such as “suffering from burnout” in our conclusions, as this could incorrectly imply a clinical diagnosis.

6. Conclusions

Research indicates that females, physicians, nurses, individuals who are overweight or obese, and those with insufficient sleep may have an increased risk of burnout. These factors are considered potential independent risk factors for burnout. Additionally, the risk of burnout gradually develops over time, particularly among healthcare workers, and is exacerbated by overtime work. However, this gradual progression of burnout also presents an opportunity for timely intervention. Therefore, implementing effective measures to alleviate burnout is essential. Medical organizations should regularly monitor employees’ workload and mental health status, develop and strictly enforce policies to limit overtime work, and ensure sufficient rest for staff. They should also offer targeted support programs for those frequently working overtime, including stress management training, psychological counseling, and guidance on maintaining a healthy lifestyle. These measures decrease the risk of burnout and improve healthcare workers’ well-being and productivity, ultimately contributing to the sustainability and quality of healthcare services.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Institutional Review Board Statemen

Informed consent was obtained, with subjects advised that participation was voluntary with information kept confidential.

Author Contributions

YHC involved in conception of study, acquisition of data, data entry, interpretation of results and drafting manuscript. GPJ involved in acquisition of data and finalization of manuscript. CWY involved in acquisition of data and data entry. CHL involved in conception of study, acquisition of data, interpretation of results and finalization of manuscript. YHC, GPJ, and CHL participated in the writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (grant CSH-2025-A-028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, reviewed and approved the study protocol on January 24, 2025 (CSMUH No: CS1-24226). All research procedures adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring confidentiality, anonymity, and proper handling of the secondary data throughout the study.

Abbreviations

CBI Copenhagen burnout inventory

HPBL High PB level

LAFF leisure activities with family and friends

PB Personal burnout

References

- Guseva Canu, I.; Marca, S.C.; Dell’Oro, F.; Balázs, Á.; Bergamaschi, E.; Besse, C.; et al. Harmonized definition of occupational burnout: A systematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scand J Work Environ Health 2021, 47, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Greenglass, E.R. Introduction to special issue on burnout and health. Psychology & Health 2001, 16, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, S. Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local and regional anesthesia 2020, 13, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Counseling and dynamics: Treating the end-stage person. Job stress and burnout 1982, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, G.; Perski, A.; Osika, W.; Savic, I. Stress-related exhaustion disorder – clinical manifestation of burnout? A review of assessment methods, sleep impairments, cognitive disturbances, and neuro-biological and physiological changes in clinical burnout. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2015, 56, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Hoogduin, K.; Schaap, C.; Kladler, A. On the clinical validity of the maslach burnout inventory and the burnout measure. Psychology & Health 2001, 16, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiye, T.; Vukčević, B.; Čabarkapa, M. Resilience as a moderator in the relationship between burnout and subjective well-being among medical workers in Serbia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vojnosanitetski pregled 2021, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Meier, S.T. Burnout and depression in nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2021, 124, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.S.; Cook, E.F.; Puopolo, A.L.; Burstin, H.R.; Cleary, P.D.; Brennan, T.A. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? Journal of General Internal Medicine 2000, 15, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol, R.; Mokkink, H.; Smits, A.; Van Eijk, J.; Beek, M.; Mesker, P.; et al. Work Satisfaction of General Practitioners and the Quality of Patient Care. Family Practice 1985, 2, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Bechamps, G.; Russell, T.; Dyrbye, L.; Satele, D.; et al. Burnout and Medical Errors Among American Surgeons. Annals of Surgery 2010, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.; Grosse Frie, K.; Blum, K.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Klein, J.; Grosse Frie, K.; et al. Burnout and perceived quality of care among German clinicians in surgery. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2010, 22, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-H.; Huang, N.; Chien, L.-Y.; Chiang, J.-H.; Chiou, S.-T. Work hours and turnover intention among hospital physicians in Taiwan: does income matter? BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Co, H.; Chung, H.; Kim, H.J.S.K.H.; Union, M.W. Current status of work condition of healthcare workforce 2016. 2016.

- Chiou, S.-T.; Chiang, J.-H.; Huang, N.; Wu, C.-H.; Chien, L.-Y. Health issues among nurses in Taiwanese hospitals: National survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2013, 50, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Odagiri, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimomitsu, T.; Theorell, T.; et al. Association of overtime work hours with various stress responses in 59,021 Japanese workers: Retrospective cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, K.; Wierzbicka, A.; Matuszczyk, M.; Matuszczyk, M.; Wichniak, A. Sleep among primary care physicians–Association with overtime, night duties and strategies to counteract poor sleep quality. Journal of Sleep Research 2021, 30, e13031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.-R.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, D.-W.; Kang, M.-Y. The combined effect of long working hours and individual risk factors on cardiovascular disease: An interaction analysis. Journal of Occupational Health 2021, 63, e12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.; Day, T.; Murrells, T.; Dall’Ora, C.; Rafferty, A.M.; Griffiths, P.; et al. Cross-sectional examination of the association between shift length and hospital nurses job satisfaction and nurse reported quality measures. BMC Nursing 2017, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanessa, M. D’Sa J. P.A.F.N.A.-D.; Gladys P. Potential Dangers of Nursing Overtime in Critical Care. Nursing Leadership 2018, 31, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.-L.; Sim, P.-L.; Goh, F.-Q.; Leong, C.-M.; Ting, H. Overwork and overtime on turnover intention in non-luxury hotels: Do incentives matter? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights 2020, 3, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-L.; Li, R.-H.; Fang, S.-Y.; Tang, F.-C. Work Hours and Difficulty in Leaving Work on Time in Relation to Work-to-Family Conflict and Burnout Among Female Workers in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikow, J.; Padovani, A.; Miller, M. Frontline physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: national survey findings. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Chiu, A.W.H. Development and validation of an occupational burnout inventory. Taiwan J Public Health 2008, 27, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Gill, T.M.; Allore, H.G. Modeling Repeated Time-to-event Health Conditions with Discontinuous Risk Intervals. An Example of a Longitudinal Study of Functional Disability among Older Persons 2008, 47, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mukhopadhyay, K. Survival analysis in clinical trials: Basics and must know areas. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Seals, S.; Aban, I. Survival analysis and regression models. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology 2014, 21, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.K.; Khanna, P.; Kishore, J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. International journal of Ayurveda research 2010, 1, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, M.J.; Clark, T.G.; Love, S.B.; Altman, D.G. Survival Analysis Part II: Multivariate data analysis – an introduction to concepts and methods. British Journal of Cancer 2003, 89, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timeline of key decisions for COVID-19 epidemic prevention20230501. Available online: https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/ch/cp-4822-74641-205.html (accessed on 1/8).

- Timeline of key decisions for COVID-19 epidemic prevention20210714. Available online: https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/ch/cp-4822-62153-205.html (accessed on 1/8).

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Herrin, J.; Dovidio, J.; Cunningham, B.; Yeazel, M.; et al. A Longitudinal Study Exploring Learning Environment Culture and Subsequent Risk of Burnout Among Resident Physicians Overall and by Gender. Mayo Clinic proceedings 2021, 96, 2168–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; Freischlag, J. Relationship Between Work-Home Conflicts and Burnout Among American Surgeons: A Comparison by Sex. Archives of Surgery 2011, 146, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, G.E. Stresses on women physicians: Consequences and coping techniques. Depression and Anxiety 2003, 17, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeluru, H.; Newton, H.L.; Kapoor, R. Physician Burnout Through the Female Lens: A Silent Crisis. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Sinsky, C.A.; Awad, K.M.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Fiscus, L.C.; et al. Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 2019, 170, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuor, R.A.; Mutungi, K.; Anyango, R.; Mwita, C.C. Prevalence of burnout among nurses in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Rangarajan, S.; Lear, S.A.; AlHabib, K.F.; Mohan, V.; et al. Association of estimated sleep duration and naps with mortality and cardiovascular events: a study of 116 632 people from 21 countries. European Heart Journal 2019, 40, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlaine, A.; Sauvet, F.; Gomez-Merino, D.; Elbaz, M.; Delafosse, J.Y.; Leger, D.; et al. Association between insomnia symptoms, job strain and burnout syndrome: a cross-sectional survey of 1300 financial workers. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Purí, C.; Plaza-Ccuno, J.N.R.; Soriano-Moreno, A.N.; Calizaya-Milla, Y.E.; Saintila, J. Burnout Fat Intake, and Body Mass Index in Health Professionals Working in a Public Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization Provision, and Financing 2023, 60, 00469580231189601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza e Silva, D.; das Merces, M.C.; Lua, I.; Coelho, J.M.F.; Santana, A.I.C.; Reis, D.A.; et al. Association between burnout syndrome and obesity: A cross-sectional population-based study. Work 2023, 74, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Yamauchi, K. The effect of quality of overtime work on nurses’ mental health and work engagement. Journal of Nursing Management 2018, 26, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltorki, Y.; Abdallah, O.; Riaz, S.; Mahmoud, S.; Saad, M.; Ez-Eldeen, N.; et al. Burnout among pharmacy professionals in Qatar: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0267438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamebozorgi, M.H.; Karamoozian, A.; Bardsiri, T.I.; Sheikhbardsiri, H. Nurses Burnout Resilience, and Its Association With Socio-Demographic Factors During COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Limbrecht-Ecklundt, K.; Walter, S.; Spohrs, J.; Beschoner, P. Correlations of the “Work–Family Conflict” With Occupational Stress—A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Employees. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton Skurak, H.; Malinen, S.; Näswall, K.; Kuntz, J.C. Employee wellbeing: The role of psychological detachment on the relationship between engagement and work–life conflict. Economic and Industrial Democracy 2018, 42, 116–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, J.R. Loss to follow-up. Evidence-based spine-care journal 2011, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).