Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Double-Code Hypothesis of Ageing: Ageing as a Consequence of the Intergenerational Inheritance of a Dual Code of Information—The Genome and the Epigenome.

2.1. What Is Inherited Intergenerationally, and How?

2.2. What Is Life?

2.3. Why Does Ageing Exist?

2.4. Interplay Between Genome and Epigenome: The Ratchet Mechanisms

2. What Distinguishes the Proposed Description of Ageing in This Work from Current Ageing Studies?

- Evolutionary Theories of Ageing: These theories apply principles of natural selection and evolutionary trade-offs to explain why ageing exists at all, rather than being eliminated by evolution. Three classical theories are: Mutation Accumulation Theory, proposed by Peter Medawar [37], Antagonistic Pleiotropy Theory, proposed by George C. Williams [38] and Disposable Soma Theory, proposed by Thomas Kirkwood [39].

- Damage (Stochastic) Theories of Ageing: These propose that ageing results from random but cumulative damage to cells, tissues, and molecules, eventually overwhelming the body’s repair systems over time.

- Programmatic Theories of Ageing: These suggest that ageing is (at least partially) driven by genetic or regulatory programs, as if ageing is an extension or byproduct of developmental processes. This perspective is largely supported by the observation that there are conserved mechanisms, such as dietary restriction [40], as well as mutations or treatments that affect ageing.

3.1. Evolutionary Theories of Ageing

3.2. Damage Theories of Ageing and Programmatic Theories of Ageing

3.3. Trade-offs in Ageing

3.4. Information-Based Conception of Life and Ageing

- 1)

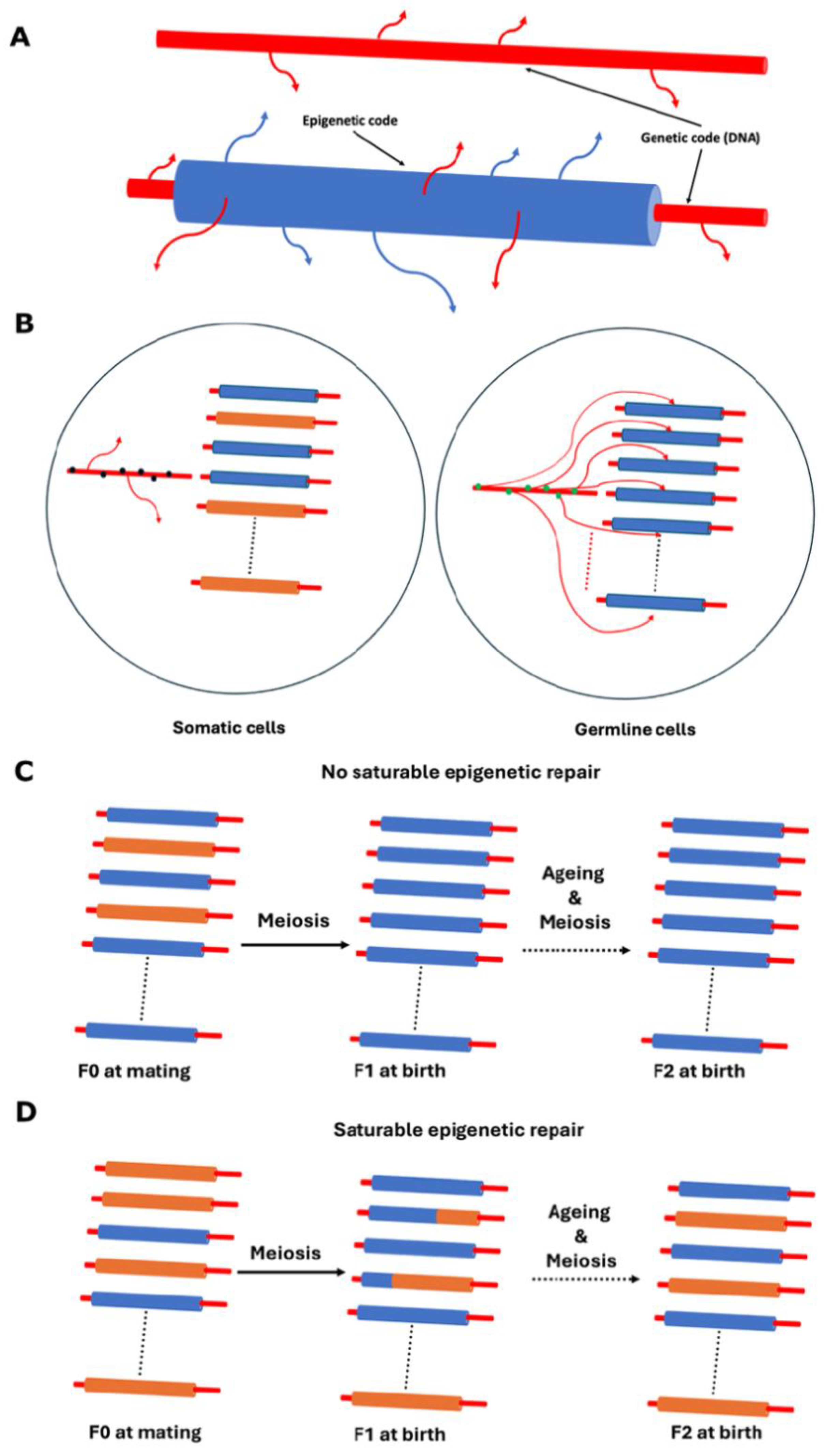

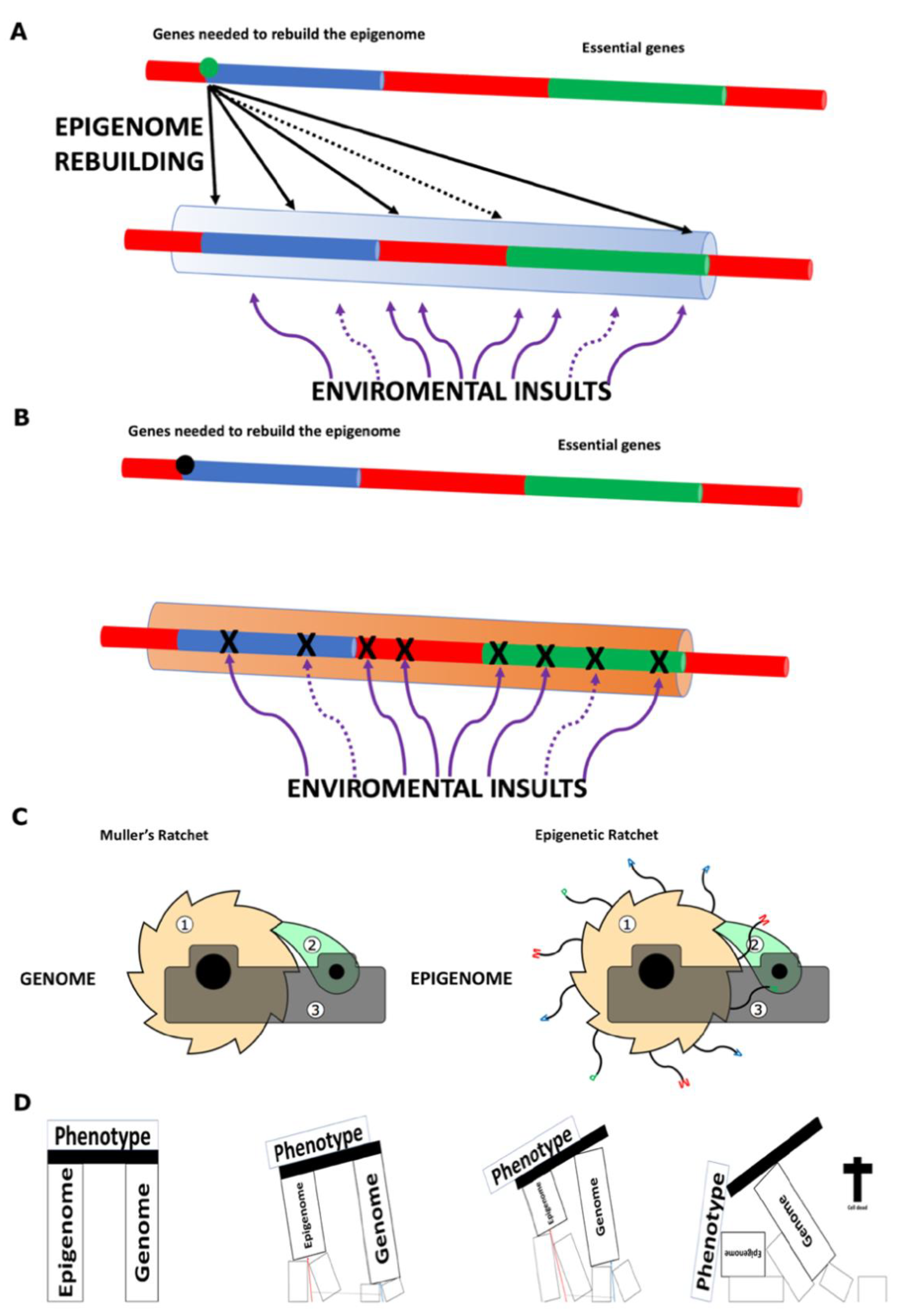

- Biological information is always composed of both the genome and the epigenome, meaning that a cells or individual’s phenotype is determined in ‘real time’ by the specific genomic and epigenomic code it carries (see Figure 2D).

- 2)

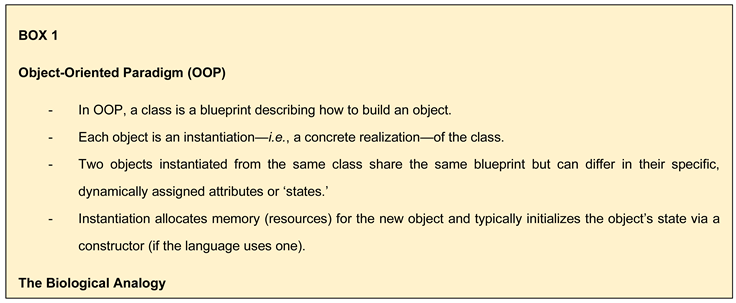

- To describe the intergenerational transfer of information between individuals (parents and offspring), I suggest borrowing the concept of ‘instantiation’ from the Object Oriented Programming Paradigm (OOP) in computer science, a concept I have been employing throughout this paper.

- Analogy of Biological Codes: The most appropriate analogy for describing the two biological codes of information (genome and epigenome) is not the digital-analogue pair suggested by Sinclair and LaPlante [6], but rather the OOP paradigm. In the digital-analogue comparison, both systems convey the same message through different formats. In contrast, the OOP analogy better captures the interplay between the genome and epigenome. OOP introduces additional coding capabilities to the epigenetic code (the derived code) that the genome (the original code) does not inherently possess. Although the genome encodes the instructions for constructing the epigenome, once built, the epigenome functions as a semi-independent code. While not a perfect analogy, the OOP paradigm is the closest conceptual framework for understanding the genome-epigenome relationship.

- A further notable difference between the proposal defended in this paper and that of Sinclair and colleagues is the causative relationship between DNA mutations and epimutations. According to Sinclair and colleagues, DNA mutations drive the emergence of epimutations [5,62,75], whereas the framework proposed here posits the reverse: that epimutations can lead to DNA mutations (see Figure 2A,B). While it is likely that both factors contribute to the overall defect burden, my view strongly supports epimutations as the primary driver, ultimately leading to the progressive accumulation of DNA mutations over time. A recent study has shown the correlation between mutations and DNA methylation epimutations in cancer samples, though it has not yet determined which is the primary causal agent [76]. I propose that we consider the dual protection mechanism hypothesized to exist between the genome and the epigenome, as suggested by the study conducted by Monroe et al. (2022) [32] (see Figure 2A,B).

- Perspective on Ageing: Ageing is not a design flaw. While it is often perceived as a flaw when analysed from an individual human perspective [74], this perception arises from our recognition of ageing’s negative implications for individuals. From a teleological viewpoint, ageing appears flawed because humans would never intentionally design a process with such detrimental consequences. However, ageing did not arise from intentional design—it emerged randomly, guided by Weismannian logic. While ageing is detrimental to individuals, it is essential for species maintenance and evolution, acting as a trade-off that supports the perpetuation of biological information across generations.

- The Instantiation Mechanisms: Building on the flaw proposed in today’s biological knowledge framework and inspired by the OOP paradigm analogy, this paper proposes that new ‘instances’ (offspring) are created using both genetic and epigenetic information inherited from parental cells or individuals. Once formed, the somatic cells of a new individual can modify the epigenome to produce differentiated cells but cannot restore the ‘young epigenome.’ This capability is exclusive to germline cells, which create new ‘instances’ that do not contribute to the parent’s body. Some epigenetic information in somatic cells exists in its current state because it was inherited from progenitors and cannot be reconstructed from the individual’s genome. This is not due to a lack of necessary information in the genome but rather to the restricted access somatic cells have to this information. Consequently, the epigenetic code of an individual functions as a partially independent code from the genome.

- Phenotype as a Dynamic Outcome: The phenotype of a given cell or organism is determined by the ‘real-time’ biological information contained in its genome and epigenome. For multicellular organisms, a developmental program runs alongside the ageing program from the moment of ‘instantiation.’ Many ageing-associated diseases arise from the intrinsic loss of information—primarily epigenetic but also genetic—which ultimately leads to the organism’s death when it no longer retains the necessary information to sustain life.

4. The Epigenetics of Ageing

4.1. Epigenetics of Long-Lived Organisms

5. Random vs. Programmed Ageing Processes: Information Maintenance in Unicellular vs. Multicellular Organisms

- The continuous replacement of older individuals with ‘young’, flawless newborns, thereby reducing the risk of extinction associated with the increasing vulnerability to external causes of death that accompany greater behavioural and structural complexity.

- The ability of complex organisms—which inherently require a developmental process—to maintain a stable balance between the creation and removal of individuals, without relying on simpler reproductive strategies such as binary fission or spore formation, which are used by less complex organisms that do not undergo proper ageing.

- An acceleration in the emergence of evolutionary novelties, by reinforcing the need for population renewal. This mechanism helped overcome the limits imposed by external threats on organismal complexity. As a result, increasingly complex organisms were able to evolve over time—organisms that would likely not have arisen in the absence of an ageing process.

6. An Empirical Proposal to Test the Nature of Ageing in a Popperian Framework—Beyond Identifying Factors that Influence Its Pace

- Fission yeast self-cross survival is a biomarker of ageing, where ageing is defined, as described in this paper, as the number of epigenetic defects accumulated in a given clone [7].

- The lower the self-cross survival value of a clone, the greater the inferred impact of accumulated epigenetic defects on the survival of its mitotically derived progeny. This reflects the influence of stochastic variation during the epigenetic copying process in mitotic divisions.

- Different clones may show different self-cross survival values due to the accumulation of distinct epigenetic defects at different epiloci.

- During meiosis, a saturable “epigenetic repair mechanism” operates, which may or may not improve fitness at any given epilocus. From the perspective of a single epilocus, the outcome is random-like due to this saturability. Improvements in fitness can be detected as increased self-cross spore survival.

- An individual cell dies when the real-time biological information it carries is no longer sufficient to sustain life (see Figure 2D).

- A clonal lineage will cease to exist when all of its mitotically derived progeny reach the same informational threshold described in point 5, i.e., when all cells from a given colony lose viability due to excessive epigenetic damage (Figure 2D).

- This creates a scenario where lethality due to old age is attributable to the epigenetic state of a clonal group of cells—that is, a population-level property rather than a purely individual one.

Author Contributions

References

- Kroemer, G.; Maier, A.B.; Cuervo, A.M.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Ferrucci, L.; Gorbunova, V.; Kennedy, B.K.; Rando, T.A.; Seluanov, A.; Sierra, F.; et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: Understanding and managing aging. Cell 2025, 188, 2043–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

- de Magalhães, J.P. An overview of contemporary theories of ageing. Nat Cell Biol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.R.; Tian, X.; Sinclair, D.A. The Information Theory of Aging Nature Aging 3, 1486–1499 (2023).

- Sinclair, D.A.; LaPlante, M.D. Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don’t Have To (Atria Books, 2019).

- Marsellach, X. A non-genetic meiotic repair program inferred from spore survival values in fission yeast wild isolates: a clue for an epigenetic ratchet-like model of ageing bioRxiv (2017).

- Marsellach, X. Ageing is not just ageing Zenodo (2025).

- Memczak, S.; Belmonte, J.C.I.; Graepel, T. Escaping ageing through Cell Annealing—a phenomenological model. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsellach, X. The Principle of Continuous Biological Information Flow as the Fundamental Foundation for the Biological Sciences. Implications for Ageing Research Preprints 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weismann, A.; Poulton, E.B.; Shipley, A.E. Thoughts upon the Musical Sense in Animals and Men. No. X. of "Essays upon Heredity and Kindred Biological Problems". Music. Times Sing. Cl. Circ. 1893, 34, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.W.S.; Leitch, H.G.; Requena, C.E.; Sun, Z.; Amouroux, R.; Roman-Trufero, M.; Borkowska, M.; Terragni, J.; Vaisvila, R.; Linnett, S.; et al. Epigenetic reprogramming enables the transition from primordial germ cell to gonocyte. Nature 2018, 555, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, J.A.; Surani, M.A. DNA methylation dynamics during the mammalian life cycle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20110328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.; Oakey, R.J. Resetting for the next generation. Mol Cell 48, 819–821 (2012).

- Kobayashi, H.; Sakurai, T.; Imai, M.; Takahashi, N.; Fukuda, A.; Yayoi, O.; Sato, S.; Nakabayashi, K.; Hata, K.; Sotomaru, Y.; et al. Contribution of Intragenic DNA Methylation in Mouse Gametic DNA Methylomes to Establish Oocyte-Specific Heritable Marks. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.D.; Chan, M.M.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Gu, H.; Gnirke, A.; Regev, A.; Meissner, A. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature 2012, 484, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, R.; Chiba, H.; Kaneda, M.; Tajima, S.; Li, E.; Jaenisch, R.; Sasaki, H. Maternal and zygotic Dnmt1 are necessary and sufficient for the maintenance of DNA methylation imprints during preimplantation development. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E. Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: a critical perspective Frontiers in Epigenetics and Epigenomics 2, 0 (2024).

- Cao, S.; Chen, Z.J. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance during plant evolution and breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1203–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moelling, K. Epigenetics and transgenerational inheritance. J. Physiol. 2023, 602, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duempelmann, L.; Skribbe, M.; Bühler, M. Small RNAs in the Transgenerational Inheritance of Epigenetic Information. Trends Genet. 2020, 36, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Valencia, M.M.; Yu, Y.; Ouchi, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Lande, K.; Williams, A.E.; Fresia, C.; Kurita, M.; et al. Transgenerational inheritance of acquired epigenetic signatures at CpG islands in mice. Cell 2023, 186, 715–731.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsellach, X. A non-Lamarckian model for the inheritance of the epigenetically-coded phenotypic characteristics: a new paradigm for Genetics, Genomics and, above all, Ageing studies bioRxiv (2018).

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process IBM journal of research and development 5, 183–191 (1961).

- Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication The Bell System Technical Journal 27, 379–423 (1948).

- Szilard, L. über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen Zeitschrift für Physik 53, 840–856 (1929).

- Mizraji, E. The biological Maxwell's demons: exploring ideas about the information processing in biological systems. Theory Biosci. 2021, 140, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, T.D.; Freeze, H. Thermus aquaticus gen. n. and sp. n., a nonsporulating extreme thermophile. Journal of bacteriology 1969, 98, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, J.G.; Srikant, T.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Becker, C.; Lensink, M.; Exposito-Alonso, M.; Klein, M.; Hildebrandt, J.; Neumann, M.; Kliebenstein, D.; et al. Mutation bias reflects natural selection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 2022, 602, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, V.N.; Anderson, B.; Barlit, H.; Barré, B.; Beck, S.; Behrouz, B.; Belsky, D.W.; Chaix, A.; Chamoli, M.; Chen, B.H.; et al. Disagreement on foundational principles of biological aging. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, J.R.; Gladyshev, V.N. We need to shift the focus of aging research to aging itself. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.A.; Kennedy, B.K.; Anglas, U.; Bronikowski, A.M.; Deelen, J.; Dufour, F.; Ferbeyre, G.; Ferrucci, L.; Franceschi, C.; Frasca, D.; et al. Lack of consensus on an aging biology paradigm? A global survey reveals an agreement to disagree, and the need for an interdisciplinary framework. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 191, 111316–111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medawar, P.B. An unsolved problem of biology (1952).

- Williams, G.C. PLEIOTROPY, NATURAL SELECTION, AND THE EVOLUTION OF SENESCENCE Evolution 11, 398–411 (1957).

- Kirkwood, T.B. Evolution of ageing. Nature 270, 301–304 (1977).

- McCay, C.M.; Crowell, M.F.; Maynard, L.A. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size: one figure The journal of Nutrition 10, 63–79 (1935).

- Mc Auley, M.T. The evolution of ageing: classic theories and emerging ideas. Biogerontology 2024, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamplona, R.; Jové, M.; Gómez, J.; Barja, G. Programmed versus non-programmed evolution of aging. What is the evidence? Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 175, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, V.N.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Clarke, S.G.; Cuervo, A.M.; Fiehn, O.; de Magalhães, J.P.; Mau, T.; Maes, M.; Moritz, R.L.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Molecular damage in aging. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, P.; Dag, B.; Carazo, P.; Sultanova, Z. Sex-specific paternal age effects on offspring quality in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Evol. Biol. 2023, 36, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.F.; Francesconi, M.; Hidalgo-Carcedo, C.; Lehner, B. Maternal age generates phenotypic variation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2017, 552, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, C.; Piat, A.; Schlich, P.; Ducau, J.; Bregliano, J.-C.; Aguilaniu, H.; Laurençon, A. Parental age effect on the longevity and healthspan in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging 2023, 15, 11720–11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi, K.; Pizzari, T.; Sepil, I.; Archer, R.; Connallon, T. What does not kill you makes you stronger? Effects of paternal age at conception on fathers and sons. Evolution 2024, 78, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, C.; Chang, J.; Gensch, E.; Rudner, A.; Tabtiang, R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 1993, 366, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, L.; Thornton, J.; Bates, G. The new science of ageing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366, 6–8 (2011).

- Partridge, L. The new biology of ageing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365, 147–154 (2010).

- Goldsmith, T.C. On the programmed/non-programmed aging controversy. Biochem. (Moscow) 2012, 77, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.J.; Gems, D.; Harshman, L.G.; Oldham, S.; Stocker, H.; Hafen, E.; Leevers, S.J.; Partridge, L. Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Science 2001, 292, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M.; Powers, R.W.; Steffen, K.K.; Westman, E.A.; Hu, D.; Dang, N.; Kerr, E.O.; Kirkland, K.T.; Fields, S.; Kennedy, B.K. Regulation of Yeast Replicative Life Span by TOR and Sch9 in Response to Nutrients. Science 2005, 310, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaeberlein, M.; McVey, M.; Guarente, L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2570–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, D.A.; Guarente, L. Extrachromosomal rDNA Circles— A Cause of Aging in Yeast. Cell 1997, 91, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.; Dorman, J.B.; Rodan, A.; Kenyon, C. daf-16 : An HNF-3/forkhead Family Member That Can Function to Double the Life-Span of Caenorhabditis elegans Science 278, 1319–1322 (1997).

- Giannakou, M.E.; Goss, M.; Partridge, L. Role of dFOXO in lifespan extension by dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster: not required, but its activity modulates the response. Aging Cell 7, 187–198 (2008).

- Apfeld, J.; O'COnnor, G.; McDonagh, T.; DiStefano, P.S.; Curtis, R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 3004–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, W.; Morantte, I.; Rodrigues, A.P.C.; Manning, G.; Montminy, M.; Shaw, R.J.; Dillin, A. Lifespan extension induced by AMPK and calcineurin is mediated by CRTC-1 and CREB. Nature 2011, 470, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillin, A.; Hsu, A.-L.; Arantes-Oliveira, N.; Lehrer-Graiwer, J.; Hsin, H.; Fraser, A.G.; Kamath, R.S.; Ahringer, J.; Kenyon, C. Rates of Behavior and Aging Specified by Mitochondrial Function During Development. Science 2002, 298, 2398–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang; J.H.; Hayano; M.; Griffin; P.T.; Amorim; J.A.; Bonkowski; M.S.; Apostolides; J.K.; Salfati; E.L.; Blanchette; M.; Munding; E.M.; Bhakta; M.; Chew; Y.C.; Guo; W.; Yang; X.; Maybury-Lewis; S.; Tian; X.; Ross; J.M.; Coppotelli; G.; Meer; M.V.; Rogers-Hammond; R.; Vera; D.L.; Lu; Y.R.; Pippin; J.W.; Creswell; M.L.; Dou; Z.; Xu; C.; Mitchell; S.J.; Das; A.; O’Connell; B.L.; Thakur; S.; Kane; A.E.; Su; Q.; Mohri; Y.; Nishimura; E.K.; Schaevitz; L.; Garg; N.; Balta; A.M.; Rego; M.A.; Gregory-Ksander; M.; Jakobs; T.C.; Zhong; L.; Wakimoto; H.; El Andari; J.; Grimm; D.; Mostoslavsky; R.; Wagers; A.J.; Tsubota; K.; Bonasera; S.J.; Palmeira; C.M.; Seidman; J.G.; Seidman; C.E.; Wolf; N.S.; Kreiling; J.A.; Sedivy; J.M.; Murphy; G.F.; Green; R.E.; Garcia; B.A.; Berger; S.L.; Oberdoerffer; P.; Shankland; S.J.; Gladyshev; V.N.; Ksander; B.R.; Pfenning; A.R.; Rajman; L.A.; Sinclair; D.A. Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging. Cell S0092–8674(22)01570 (2023).

- Lu, Y.; Brommer, B.; Tian, X.; Krishnan, A.; Meer, M.; Wang, C.; Vera, D.L.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, D.; Bonkowski, M.S.; et al. Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature 2020, 588, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, D.A.; Oberdoerffer, P. The ageing epigenome: damaged beyond repair Ageing Res Rev 8, 189–198 (2009).

- Fossel, M. ‘We need to get comfortable with being wrong about aging’. (available at https://longevity.technology/news/we-need-to-get-comfortable-with-being-wrong-about-aging/).

- Ribeiro, M.G.L.; Larentis, A.L.; Caldas, L.A.; Garcia, T.C.; Terra, L.L.; Herbst, M.H.; Almeida, R.V. On the debate about teleology in biology: the notion of "teleological obstacle". Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos 2015, 22, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, E. EL DEBATE FILOSÓFICO DE LA TELEOLOGÍA EN LA EXPLICACIÓN BIOLÓGICA:¿ UN MAL NECESARIO? Journal of Teleological Science ( 2021.

- Darwin, C. On the origin of species (D. Appleton and Co., New York : 1871).

- Newton, I. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Jussu Societatis Regiae, London, 1687).

- Siregar, P.; Julen, N.; Hufnagl, P.; Mutter, G. A general framework dedicated to computational morphogenesis Part II – Knowledge representation and architecture. Biosystems 2018, 173, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarck, J.-B.P.A.D.M. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (Verdière, Paris, 1815).

- Lamarck, J.-B.P.A.D.M. Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l’histoire naturelle des animaux (Dentu & L’Auteur, Paris, 1809).

- Krakauer, D.; Bertschinger, N.; Olbrich, E.; Flack, J.C.; Ay, N. The information theory of individuality. Theory Biosci 139, 209–223 (2020).

- de Magalhães, J.P. Ageing as a software design flaw. Genome Biol 24, 51 (2023).

- Oberdoerffer, P.; Michan, S.; McVay, M.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Vann, J.; Park, S.-K.; Hartlerode, A.; Stegmuller, J.; Hafner, A.; Loerch, P.; et al. SIRT1 Redistribution on Chromatin Promotes Genomic Stability but Alters Gene Expression during Aging. Cell 2008, 135, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, Z.; Li, A.; Evans, D.S.; Cummings, S.; Ideker, T. Somatic mutation as an explanation for epigenetic aging. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, V.; Smith, R.; Ma, S.; Cutler, R. Genomic 5-methyldeoxycytidine decreases with age. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9948–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wareham, K.A.; Lyon, M.F.; Glenister, P.H.; Williams, E.D. Age related reactivation of an X-linked gene. Nature 1987, 327, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, V.L.; Jones, P.A. DNA Methylation Decreases in Aging But Not in Immortal Cells. Science 1983, 220, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanyushin, B.F.; E Nemirovsky, L.; Klimenko, V.V.; Vasiliev, V.K.; Belozersky, A.N. The 5-methylcytosine in DNA of rats. Tissue and age specificity and the changes induced by hydrocortisone and other agents.. 1973, 19, 138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.F.; Ballestar, E.; Paz, M.F.; Ropero, S.; Setien, F.; Ballestar, M.L.; Heine-Suñer, D.; Cigudosa, J.C.; Urioste, M.; Benitez, J.; et al. From The Cover: Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10604–10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-M.; Shibata, D. Tracing ancestry with methylation patterns: most crypts appear distantly related in normal adult human colon. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004, 4, 8–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, C.A. Are somatic cells inherently deficient in methylation metabolism? A proposed mechanism for DNA methylation loss, senescence and aging. Growth Dev Aging 57, 261–273 (1993).

- Dang, W.; Steffen, K.K.; Perry, R.; Dorsey, J.A.; Johnson, F.B.; Shilatifard, A.; Kaeberlein, M.; Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L. Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan. Nature 2009, 459, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarg, B.; Koutzamani, E.; Helliger, W.; Rundquist, I.; Lindner, H.H. Postsynthetic Trimethylation of Histone H4 at Lysine 20 in Mammalian Tissues Is Associated with Aging. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 39195–39201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissenbaum, H.A.; Guarente, L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2001, 410, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Gotta, M.; A Sinclair, D.; Mills, K.; McNabb, D.S.; Murthy, M.; Pak, S.M.; Laroche, T.; Gasser, S.M.; Guarente, L. Redistribution of Silencing Proteins from Telomeres to the Nucleolus Is Associated with Extension of Life Span in S. cerevisiae. Cell 1997, 89, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 14, R115 (2013).

- Gibbs, W.W. Biomarkers and ageing: The clock-watcher. Nature 2014, 508, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.-B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide Methylation Profiles Reveal Quantitative Views of Human Aging Rates. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; Reiner, A.P.; Aviv, A.; Raj, K.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Li, Y.; Stewart, J.D.; et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2019, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Horvath, S. Epigenetic ageing clocks: statistical methods and emerging computational challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, C.; Fiorito, G.; Hernandez, B.; Polidoro, S.; O’hAlloran, A.M.; Hever, A.; Ni Cheallaigh, C.; Lu, A.T.; Horvath, S.; Vineis, P.; et al. GrimAge Outperforms Other Epigenetic Clocks in the Prediction of Age-Related Clinical Phenotypes and All-Cause Mortality. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 76, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marioni, R.E.; Shah, S.; McRae, A.F.; Chen, B.H.; Colicino, E.; Harris, S.E.; Gibson, J.; Henders, A.K.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wilson, R.; Heiss, J.; Breitling, L.P.; Saum, K.-U.; Schöttker, B.; Holleczek, B.; Waldenberger, M.; Peters, A.; Brenner, H. DNA methylation signatures in peripheral blood strongly predict all-cause mortality. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Rebholz, C.M.; Braun, K.V.; Reynolds, L.M.; Aslibekyan, S.; Xia, R.; Biligowda, N.G.; Huan, T.; Liu, C.; Mendelson, M.M.; et al. Whole Blood DNA Methylation Signatures of Diet Are Associated With Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and All-Cause Mortality. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, e002766–e002766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.B.; Li, S.; Baumbach, J.; Svane, A.M.; Hjelmborg, J.; Christiansen, L.; Christensen, K.; Redmond, P.; Marioni, R.E.; Deary, I.J.; et al. DNA methylome profiling of all-cause mortality in comparison with age-associated methylation patterns. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haluza, Y.; Zoller, J.A.; Lu, A.T.; Walters, H.E.; Lachnit, M.; Lowe, R.; Haghani, A.; Brooke, R.T.; Park, N.; Yun, M.H.; Horvath, S. Axolotl epigenetic clocks offer insights into the nature of negligible senescence bioRxiv 0 (2024).

- Lu, A.T.; Fei, Z.; Haghani, A.; Robeck, T.R.; Zoller, J.A.; Li, C.Z.; Lowe, R.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Vu, H.; et al. Universal DNA methylation age across mammalian tissues. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1144–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoller, J.A.; Parasyraki, E.; Lu, A.T.; Haghani, A.; Niehrs, C.; Horvath, S. DNA methylation clocks for clawed frogs reveal evolutionary conservation of epigenetic aging. GeroScience 2023, 46, 945–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.J.; Gerber, L.; Scheu, L.; Cicciarella, R.; Zoller, J.A.; Fei, Z.; Horvath, S.; Allen, S.J.; King, S.L.; Connor, R.C.; et al. An epigenetic DNA methylation clock for age estimates in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus). Evol. Appl. 2022, 16, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Haghani, A.; Zoller, J.A.; Naderi, A.; Soltanmohammadi, E.; Farmaki, E.; Kaza, V.; Chatzistamou, I.; Kiaris, H. Methylation studies in Peromyscus: aging, altitude adaptation, and monogamy. GeroScience 2021, 44, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S.; Haghani, A.; Macoretta, N.; Ablaeva, J.; Zoller, J.A.; Li, C.Z.; Zhang, J.; Takasugi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rydkina, E.; et al. DNA methylation clocks tick in naked mole rats but queens age more slowly than nonbreeders. Nat. Aging 2021, 2, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S.; Haghani, A.; Peng, S.; Hales, E.N.; Zoller, J.A.; Raj, K.; Larison, B.; Robeck, T.R.; Petersen, J.L.; Bellone, R.R.; et al. DNA methylation aging and transcriptomic studies in horses. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Zoller, J.A.; Haghani, A.; Jasinska, A.J.; Raj, K.; Breeze, C.E.; Ernst, J.; Vaughan, K.L.; Mattison, J.A. Epigenetic clock and methylation studies in the rhesus macaque. GeroScience 2021, 43, 2441–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulton, A.; Dodds, K.G.; McRae, K.M.; Couldrey, C.; Horvath, S.; Clarke, S.M. Development of Epigenetic Clocks for Key Ruminant Species. Genes 2021, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Danson, A.F.; Rakyan, V.K.; Yildizoglu, S.; Saldmann, F.; Viltard, M.; Friedlander, G.; Faulkes, C.G. DNA methylation clocks as a predictor for ageing and age estimation in naked mole-rats, Heterocephalus glaber. Aging 2020, 12, 4394–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Chwiałkowska, K.; Rubbi, L.; Lusis, A.J.; Davis, R.C.; Srivastava, A.; Korstanje, R.; Churchill, G.A.; Horvath, S.; Pellegrini, M. A multi-tissue full lifespan epigenetic clock for mice. Aging 2018, 10, 2832–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.J.; Vonholdt, B.; Horvath, S.; Pellegrini, M. An epigenetic aging clock for dogs and wolves. Aging 2017, 9, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl, M.E.; Guo, W.; Farrell, C.; Marino, N.; Henry, J.E.; Storniolo, A.M.; Papp, J.; Li, J.J.; Horvath, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Ganz, P.A. Systematic dissection of epigenetic age acceleration in normal breast tissue reveals its link to estrogen signaling and cancer risk bioRxiv 0 (2024).

- Haefliger, S.; Chervova, O.; Davies, C.; Loh, C.; Tirabosco, R.; Amary, F.; Pillay, N.; Horvath, S.; Beck, S.; Flanagan, A.M.; et al. Epigenetic age acceleration is a distinctive trait of epithelioid sarcoma with potential therapeutic implications. GeroScience 2024, 46, 5203–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrush, K.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Gaiteri, C.; Horvath, S.; van Dyck, C.H.; Higgins-Chen, A.T.; Levine, M.E. Aging the brain: multi-region methylation principal component based clock in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2022, 14, 5641–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías-García, P.R.; Ward-Caviness, C.K.; Raffield, L.M.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wilson, R.; Gào, X.; Nano, J.; Bostom, A.; Colicino, E.; et al. DNAm-based signatures of accelerated aging and mortality in blood are associated with low renal function. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachun, D.; Lu, A.T.; Bick, A.G.; Natarajan, P.; Weinstock, J.; Szeto, M.D.; Kathiresan, S.; Abecasis, G.; Taylor, K.D.; Guo, X.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with epigenetic aging and clinical outcomes. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.C.; Binder, A.M.; Horvath, S.; Kusters, C.; Yan, Q.; Del Rosario, I.; Yu, Y.; Bronstein, J.; Ritz, B. Accelerated hematopoietic mitotic aging measured by DNA methylation, blood cell lineage, and Parkinson’s disease. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Cohen, H.; Felton, S.; Matsuyama, M.; Lowe, D.; Kabacik, S.; et al. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging 2018, 10, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Marioni, R.E.; Harris, S.E.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. DNA methylation and the epigenetic clock in relation to physical frailty in older people: the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, G.R.; Bauer, I.E.; Scaini, G.; Wu, M.-J.; Kazimi, I.F.; Valvassori, S.S.; Zunta-Soares, G.; Walss-Bass, C.; Soares, J.C.; Quevedo, J. Accelerated epigenetic aging and mitochondrial DNA copy number in bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Marioni, R.; Shah, S.; McRae, A.F.; Ritchie, S.J.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; E Harris, S.; Gibson, J.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; Pattie, A.; et al. The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Leuk. Res. 2015, 44, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Levine, A.J. HIV-1 Infection Accelerates Age According to the Epigenetic Clock. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galkin, F.; Kovalchuk, O.; Koldasbayeva, D.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Bischof, E. Stress, diet, exercise: Common environmental factors and their impact on epigenetic age. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.N.; Hodges, R.; Hanes, D.; Stack, E.; Cheishvili, D.; Szyf, M.; Henkel, J.; Twedt, M.W.; Giannopoulou, D.; Herdell, J.; et al. Potential reversal of epigenetic age using a diet and lifestyle intervention: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Aging 2021, 13, 9419–9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorito, G.; Caini, S.; Palli, D.; Bendinelli, B.; Saieva, C.; Ermini, I.; Valentini, V.; Assedi, M.; Rizzolo, P.; Ambrogetti, D.; et al. DNA methylation-based biomarkers of aging were slowed down in a two-year diet and physical activity intervention trial: the DAMA study. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, A.; Levine, M.E.; Tanaka, T.; Lu, A.T.; Chen, B.H.; Ferrucci, L.; Ritz, B.; Bandinelli, S.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Beasley, J.M.; et al. Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging 2017, 9, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Chiavellini, M. P. Chiavellini, M. Lehmann, M. D. Gallardo, M. Canatelli Mallat, D. C. Pasquini, J. A. Zoller, J. Gordevicius, M. Girard, E. Lacunza, C. B. Herenu, S. Horvath, R. G. Goya, Young Plasma Rejuvenates Blood Dna Methylation Profile, Extends Mean Lifespan And Improves Physical Appearance In Old Rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci glae071 (2024).

- Horvath, S.; Singh, K.; Raj, K.; Khairnar, S.I.; Sanghavi, A.; Shrivastava, A.; Zoller, J.A.; Li, C.Z.; Herenu, C.B.; Canatelli-Mallat, M.; et al. Reversal of biological age in multiple rat organs by young porcine plasma fraction. GeroScience 2023, 46, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, N.; Ma, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, K.; Jiang, M.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Metformin decelerates aging clock in male monkeys. Cell 2024, 187, 6358–6378.e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ros, J.; Romero-García, N.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Monleón, D.; Gordevicius, J.; Brooke, R.T.; Dromant, M.; Díaz, A.; Derevyanko, A.; Guío-Carrión, A.; et al. Small extracellular vesicles from young adipose-derived stem cells prevent frailty, improve health span, and decrease epigenetic age in old mice. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindyapina, A.V.; Cho, Y.; Kaya, A.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Castro, J.P.; Deik, A.; Gordevicius, J.; Poganik, J.R.; Clish, C.B.; Horvath, S.; et al. Rapamycin treatment during development extends life span and health span of male mice and Daphnia magna. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Zoller, J.A.; Haghani, A.; Lu, A.T.; Raj, K.; Jasinska, A.J.; Mattison, J.A.; Salmon, A.B. DNA methylation age analysis of rapamycin in common marmosets. GeroScience 2021, 43, 2413–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, G.M.; Brooke, R.T.; Watson, J.P.; Good, Z.; Vasanawala, S.S.; Maecker, H.; Leipold, M.D.; Lin, D.T.S.; Kobor, M.S.; Horvath, S. Reversal of epigenetic aging and immunosenescent trends in humans. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S.; Lu, A.T.; Cohen, H.; Raj, K. Rapamycin retards epigenetic ageing of keratinocytes independently of its effects on replicative senescence, proliferation and differentiation. Aging 2019, 11, 3238–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tsui, B.; Kreisberg, J.F.; Robertson, N.A.; Gross, A.M.; Yu, M.K.; Carter, H.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Adams, P.D.; Ideker, T. Epigenetic aging signatures in mice livers are slowed by dwarfism, calorie restriction and rapamycin treatment. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Lacunza, E.; Mallat, M.C.; Portiansky, E.L.; Gallardo, M.D.; Brooke, R.T.; Chiavellini, P.; Pasquini, D.C.; Girard, M.; Lehmann, M.; et al. Cognitive rejuvenation in old rats by hippocampal OSKM gene therapy. GeroScience 2024, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parras, A.; Vílchez-Acosta, A.; Desdín-Micó, G.; Picó, S.; Mrabti, C.; Montenegro-Borbolla, E.; Maroun, C.Y.; Haghani, A.; Brooke, R.; Maza, M.d.C.; et al. In vivo reprogramming leads to premature death linked to hepatic and intestinal failure. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-H.; Petty, C.A.; Dixon-McDougall, T.; Lopez, M.V.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Maybury-Lewis, S.; Tian, X.; Ibrahim, N.; Chen, Z.; Griffin, P.T.; et al. Chemically induced reprogramming to reverse cellular aging. Aging 2023, 15, 5966–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.J.; Quarta, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Colville, A.; Paine, P.; Doan, L.; Tran, C.M.; Chu, C.R.; Horvath, S.; Qi, L.S.; et al. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Platero-Luengo, A.; Hatanaka, F.; Hishida, T.; Li, M.; Lam, D.; Kurita, M.; Beyret, E.; et al. In Vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167, 1719–1733.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapasset, L.; Milhavet, O.; Prieur, A.; Besnard, E.; Babled, A.; Aït-Hamou, N.; Leschik, J.; Pellestor, F.; Ramirez, J.-M.; De Vos, J.; et al. Rejuvenating senescent and centenarian human cells by reprogramming through the pluripotent state. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2248–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, R.M.; Strati, K.; Li, H.; Tejera, A.; Schoeftner, S.; Ortega, S.; Serrano, M.; Blasco, M.A. Telomeres Acquire Embryonic Stem Cell Characteristics in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhr, S.T.; Chang, E.A.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Wang, K.; Ross, P.J.; Beyhan, Z.; Murthy, S.; Cibelli, J.B.; Pera, M. Telomere Dynamics in Human Cells Reprogrammed to Pluripotency. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdon, J. Adult frogs derived from the nuclei of single somatic cells. Dev. Biol. 1962, 4, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmut, I.; Schnieke, A.E.; McWhir, J.; Kind, A.J.; Campbell, K.H.S. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 1997, 385, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marión, R.M.; de Silanes, I.L.; Mosteiro, L.; Gamache, B.; Abad, M.; Guerra, C.; Megías, D.; Serrano, M.; Blasco, M.A. Common Telomere Changes during In Vivo Reprogramming and Early Stages of Tumorigenesis. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 8, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, K.; Semi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Shimizu, M.; Tanaka, A.; Mitsunaga, K.; Okita, K.; Osafune, K.; Arioka, Y.; Maeda, T.; et al. Premature Termination of Reprogramming In Vivo Leads to Cancer Development through Altered Epigenetic Regulation. Cell 2014, 156, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, M.; Mosteiro, L.; Pantoja, C.; Cañamero, M.; Rayon, T.; Ors, I.; Graña, O.; Megías, D.; Domínguez, O.; Martínez, D.; et al. Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells with totipotency features. Nature 2013, 502, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Moqri, M.; Maybury-Lewis, S.Y.; Rogers-Hammond, R.; de Jong, T.A.; Parker, A.; Rasouli, S.; Schöler, H.R.; Sinclair, D.A.; Sebastiano, V. Mechanisms, pathways and strategies for rejuvenation through epigenetic reprogramming Nature Aging (2023).

- Klausner, R. You Can Live Longer! (available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Elt4xGalQu4&t=1s).

- Hochedlinger, K.; Jaenisch, R. Induced Pluripotency and Epigenetic Reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a019448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.-N.; Rong, Z.; Xu, Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 474, 212–215 (2011).

- Lister, R.; Pelizzola, M.; Kida, Y.S.; Hawkins, R.D.; Nery, J.R.; Hon, G.; Antosiewicz-Bourget, J.; O’mAlley, R.; Castanon, R.; Klugman, S.; et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2011, 471, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Doi, A.; Wen, B.; Ng, K.; Zhao, R.; Cahan, P.; Kim, J.; Aryee, M.J.; Ji, H.; Ehrlich, L.I.R.; et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2010, 467, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, J.M.; Liu, S.; Figueroa, M.E.; Kulalert, W.; Eminli, S.; Tan, K.Y.; Apostolou, E.; Stadtfeld, M.; Li, Y.; Shioda, T.; et al. Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Okada, Y.; Aoi, T.; Okada, A.; Takahashi, K.; Okita, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Koyanagi, M.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; et al. Variation in the safety of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.J.; Hazen, J.L.; Nazor, K.L.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Gifford, W.; Martin, G.; Kupriyanov, S.; Baldwin, K.K. Adult mice generated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2009, 461, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voituron, Y.; de Fraipont, M.; Issartel, J.; Guillaume, O.; Clobert, J. Extreme lifespan of the human fish ( Proteus anguinus ): a challenge for ageing mechanisms. Biol. Lett. 2010, 7, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beccari, E.; Capdevila, P.; Salguero-Gómez, R.; Carmona, C.P. Worldwide diversity in mammalian life histories: Environmental realms and evolutionary adaptations. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.; Prego, A.; Olivé, L.; Genovart, M.; Oro, D.; Hernández-Matías, A. Adaptations to marine environments and the evolution of slow-paced life histories in endotherms. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennisi, E. Greenland shark may live 400 years, smashing longevity record Science Magazine 11, (2016).

- Glastad, K.M.; Roessler, J.; Gospocic, J.; Bonasio, R.; Berger, S.L. Long ant life span is maintained by a unique heat shock factor. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Opachaloemphan, C.; Carmona-Aldana, F.; Mancini, G.; Mlejnek, J.; Descostes, N.; Sieriebriennikov, B.; Leibholz, A.; Zhou, X.; Ding, L.; et al. Insulin signaling in the long-lived reproductive caste of ants. Science 2022, 377, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoller, J.A.; Lu, A.T.; Haghani, A.; Horvath, S.; Robeck, T. Enhancing epigenetic aging clocks in cetaceans: accurate age estimations in small endangered delphinids, killer whales, pilot whales, belugas, humpbacks, and bowhead whales. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A.; Risse, J.; Sepers, B.; van Oers, K. Independent avian epigenetic clocks for aging and development bioRxiv 0 (2024).

- Li, C.Z.; Haghani, A.; Yan, Q.; Lu, A.T.; Zhang, J.; Fei, Z.; Ernst, J.; Yang, X.W.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Robeck, T.R.; et al. Epigenetic predictors of species maximum life span and other life-history traits in mammals. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci-Richter, E.M.; Parrott, B.B. The rate of epigenetic drift scales with maximum lifespan across mammals. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.M.; Haghani, A.; Zoller, J.A.; Lu, A.T.; Fei, Z.; Ferguson, S.H.; Garde, E.; Hanson, M.B.; Emmons, C.K.; Matkin, C.O.; Young, B.G.; Koski, W.R.; Horvath, S. DNA methylation-based biomarkers for ageing long-lived cetaceans. Mol Ecol Resour ( 2023. [CrossRef]

- Crofts, S.J.C.; Latorre-Crespo, E.; Chandra, T. DNA methylation rates scale with maximum lifespan across mammals. Nat. Aging 2023, 4, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, N.A.; Brown, J.L.; Zoller, J.A.; Haghani, A.; Yao, M.; Bagryanova, L.R.; Campana, M.G.; Maldonado, J.E.; Raj, K.; Schmitt, D.; et al. Epigenetic clock and methylation studies in elephants. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, G.S.; Adams, D.M.; Haghani, A.; Lu, A.T.; Zoller, J.; Breeze, C.E.; Arnold, B.D.; Ball, H.C.; Carter, G.G.; Cooper, L.N.; et al. DNA methylation predicts age and provides insight into exceptional longevity of bats. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Mamoshina, P.; Vanhaelen, Q.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Moskalev, A.; Aliper, A. Artificial intelligence for aging and longevity research: Recent advances and perspectives. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 49, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, J.; Iniesta, R.; Lewis, C.M. Metabolomic age (MileAge) predicts health and life span: A comparison of multiple machine learning algorithms. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantikainen, E.; Weichenberger, C.X.; Dordevic, N.; Hernandes, V.V.; Foco, L.; Gögele, M.; Melotti, R.; Pattaro, C.; Ralser, M.; Amari, F.; Farztdinov, V.; Mülleder, M.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Rainer, J.; Domingues, F.S. Identifying Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers for Age-Related Morbidity in a Population-Based Cohort - the Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study medRxiv 0 (2024).

- Cohen, A.A.; Ferrucci, L.; Fülöp, T.; Gravel, D.; Hao, N.; Kriete, A.; Levine, M.E.; Lipsitz, L.A.; Rikkert, M.G.M.O.; Rutenberg, A.; Stroustrup, N.; Varadhan, R. A complex systems approach to aging biology Nature Aging 2, 580–591 (2022).

- Menni, C.; Kastenmüller, G.; Petersen, A.K.; Bell, J.T.; Psatha, M.; Tsai, P.-C.; Gieger, C.; Schulz, H.; Erte, I.; John, S.; et al. Metabolomic markers reveal novel pathways of ageing and early development in human populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkin, F.; Mamoshina, P.; Aliper, A.; Putin, E.; Moskalev, V.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Zhavoronkov, A. Human Gut Microbiome Aging Clock Based on Taxonomic Profiling and Deep Learning. iScience 2020, 23, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokzijl, F.; Janssen, R.; Van Boxtel, R.; Cuppen, E. MutationalPatterns: comprehensive genome-wide analysis of mutational processes. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentieri, M.A.; Xiao, S.; Bennett, D.; Winchester, L.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Ghose, U.; Albukhari, A.; Yao, P.; Mazidi, M.; Lv, J.; et al. Proteomic aging clock predicts mortality and risk of common age-related diseases in diverse populations. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2450–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Pilling, L.C.; Atkins, J.L.; Fortinsky, R.H.; Kuchel, G.A.; Diniz, B.S. Proteomic aging clock (PAC) predicts age-related outcomes in middle-aged and older adults. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, L.; Lehallier, B.; de Vries, H.E.; Middeldorp, J. Markers of aging: Unsupervised integrated analyses of the human plasma proteome. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1112109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehallier, B.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Johnson, A.A. Data mining of human plasma proteins generates a multitude of highly predictive aging clocks that reflect different aspects of aging. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyshkovskiy, A.; Kholdina, D.; Ying, K.; Davitadze, M.; Molière, A.; Tongu, Y.; Kasahara, T.; Kats, L.M.; Vladimirova, A.; Moldakozhayev, A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Khasanova, U.; Moqri, M.; Van Raamsdonk, J.M.; Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Abe, T.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Gladyshev, V.N. Transcriptomic Hallmarks of Mortality Reveal Universal and Specific Mechanisms of Aging, Chronic Disease, and Rejuvenation bioRxiv 1 (2024).

- Sun, E.D.; Zhou, O.Y.; Hauptschein, M.; Rappoport, N.; Xu, L.; Negredo, P.N.; Liu, L.; Rando, T.A.; Zou, J.; Brunet, A. Spatial transcriptomic clocks reveal cell proximity effects in brain ageing. Nature 2024, 638, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Hodar, J.A.; del Sol, A. Measuring biological age using a functionally interpretable multi-tissue RNA clock. Aging Cell 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyshkovskiy, A.; Ma, S.; Shindyapina, A.V.; Tikhonov, S.; Lee, S.-G.; Bozaykut, P.; Castro, J.P.; Seluanov, A.; Schork, N.J.; Gorbunova, V.; et al. Distinct longevity mechanisms across and within species and their association with aging. Cell 2023, 186, 2929–2949.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, M.T.; Sun, E.D.; George, B.M.; Liu, L.; Schaum, N.; Xu, L.; Reyes, J.M.; Goodell, M.A.; Weissman, I.L.; Wyss-Coray, T.; et al. Cell-type-specific aging clocks to quantify aging and rejuvenation in neurogenic regions of the brain. Nat. Aging 2022, 3, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzscheck, N.; Falckenhayn, C.; Söhle, J.; Kristof, B.; Siegner, R.; Werner, A.; Schössow, J.; Jürgens, C.; Völzke, H.; Wenck, H.; et al. Modeling transcriptomic age using knowledge-primed artificial neural networks. npj Aging Mech. Dis. 2021, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camillo, L.P.d.L.; Asif, M.H.; Horvath, S.; Larschan, E.; Singh, R. Histone mark age of human tissues and cell types. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadk9373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, F.; Rechsteiner, C.; Perez, K.; Praz, V.; Garcia, G.L.; Hinte, L.C.; von Meyenn, F.; Ocampo, A. ATAC-clock: An aging clock based on chromatin accessibility. GeroScience 2023, 46, 1789–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Kinde, B.; Amon, A. Gametogenesis Eliminates Age-Induced Cellular Damage and Resets Life Span in Yeast. Science 2011, 332, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proenca, A.M.; Rang, C.U.; Qiu, A.; Shi, C.; Chao, L.; Kaeberlein, M. Cell aging preserves cellular immortality in the presence of lethal levels of damage. PLOS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łapińska, U.; Glover, G.; Capilla-Lasheras, P.; Young, A.J.; Pagliara, S. Bacterial ageing in the absence of external stressors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rang, C.U.; Peng, A.Y.; Poon, A.F.; Chao, L. Ageing in Escherichia coli requires damage by an extrinsic agent. Microbiology 2012, 158, 1553–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, E.J.; Madden, R.; Paul, G.; Taddei, F.; Kirkwood, T. Aging and Death in an Organism That Reproduces by Morphologically Symmetric Division. PLOS Biol. 2005, 3, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Stearns, S.C.; Jenal, U. Senescence in a Bacterium with Asymmetric Division. Science 2003, 300, 1920–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, L.; Barton, N.H. Optimality, mutation and the evolution of ageing. Nature 362, 305–311 (1993).

- Chao, L. A model for damage load and its implications for the evolution of bacterial aging PLoS genetics 6, e1001076 (2010).

- Winkler, J.; Seybert, A.; König, L.; Pruggnaller, S.; Haselmann, U.; Sourjik, V.; Weiss, M.; Frangakis, A.S.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Quantitative and spatio-temporal features of protein aggregation in Escherichia coli and consequences on protein quality control and cellular ageing. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedel, S.; Nunns, H.; Košmrlj, A.; Semsey, S.; Trusina, A. Asymmetric Damage Segregation Constitutes an Emergent Population-Level Stress Response. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Slaughter, B.D.; Unruh, J.R.; Eldakak, A.; Rubinstein, B.; Li, R. Motility and Segregation of Hsp104-Associated Protein Aggregates in Budding Yeast. Cell 2011, 147, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Larsson, L.; Franssens, V.; Hao, X.; Hill, S.M.; Andersson, V.; Höglund, D.; Song, J.; Yang, X.; Öling, D.; et al. Segregation of Protein Aggregates Involves Actin and the Polarity Machinery. Cell 2011, 147, 959–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.M. Asymmetric Stem Cell Division and Germline Immortality. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2023, 57, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Chao, J.-C.; Cheng, K.-Y.; Leu, J.-Y. Misfolding-prone proteins are reversibly sequestered to an Hsp42-associated granule upon chronological aging. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs.220202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; McCormick, M.A.; Zheng, J.; Xie, Z.; Tsuchiya, M.; Tsuchiyama, S.; El-Samad, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Kaeberlein, M.; Kennedy, B.K.; et al. Systematic analysis of asymmetric partitioning of yeast proteome between mother and daughter cells reveals “aging factors” and mechanism of lifespan asymmetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 11977–11982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Lade, S.J.; Alberti, S.; Gross, T.; Tolić, I.M.; Walter, P. Fusion of Protein Aggregates Facilitates Asymmetric Damage Segregation. PLOS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legon, L.; Rallis, C. Genome-wide screens in yeast models towards understanding chronological lifespan regulation. Briefings Funct. Genom. 2021, 21, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, R.; Mohammad, T.; Alajmi, M.F.; Rehman, T.; Hasan, G.M.; Hussain, A.; Hassan, I. Insights into the Conserved Regulatory Mechanisms of Human and Yeast Aging. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlia-Ciommo, A.; Leonov, A.; Piano, A.; Svistkova, V.; Titorenko, V.I. Cell-autonomous mechanisms of chronological aging in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell 2014, 1, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirisola, M.G.; Longo, V.D. Yeast Chronological Lifespan: Longevity Regulatory Genes and Mechanisms. Cells 2022, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zhou, C.; Kennedy, B.K. The yeast replicative aging model. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1864, 2690–2696 (2018).

- Janssens, G.E.; Veenhoff, L.M. Evidence for the hallmarks of human aging in replicatively aging yeast. Microb. Cell 2016, 3, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoo, D.Y.; Durnford, D.G. Long-term survival of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during conditional senescence. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 5333–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Jain, P.; Shrivastava, A.; Saran, S. “Can Autophagy Stop the Clock: Unravelling the Mystery in Dictyostelium discoideum” Eds. 2020), pp. 235–258.

- Lin, I.-T.; Chao, J.-L.; Yao, M.-C.; Cohen-Fix, O. An essential role for the DNA breakage-repair protein Ku80 in programmed DNA rearrangements in Tetrahymena thermophila. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2213–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.E.; Holmes, N.R. Accumulation of DNA damages in aging Paramecium tetraurelia. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1986, 204, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Heilbronn, L.K. The health outcomes of human offspring conceived by assisted reproductive technologies (ART). J. Dev. Orig. Heal. Dis. 2017, 8, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, L.; Jeffares, D.C.; Sadée, C.Y.; Rodríguez-López, M.; A Bitton, D.; Hoti, M.; Biagosch, C.; Aravani, D.; Speekenbrink, M.; Illingworth, C.J.R.; et al. Fitness Landscape of the Fission Yeast Genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Evertts, A.G.; Levin, H.L. The Hermes transposon of Musca domestica and its use as a mutagen of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods 2009, 49, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaratne, J.; Schmidt, A.; Quandt, A.; Neo, S.P.; Saraç, O.S.; Gracia, T.; Loguercio, S.; Ahrné, E.; Xia, R.L.; Tan, K.H.; Lössner, C.; Bähler, J.; Beyer, A.; Blackstock, W.; Aebersold, R. Extensive mass spectrometry-based analysis of the fission yeast proteome: the Schizosaccharomyces pombe PeptideAtlas. Mol Cell Proteomics 12, 1741–1751 (2013).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).