Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

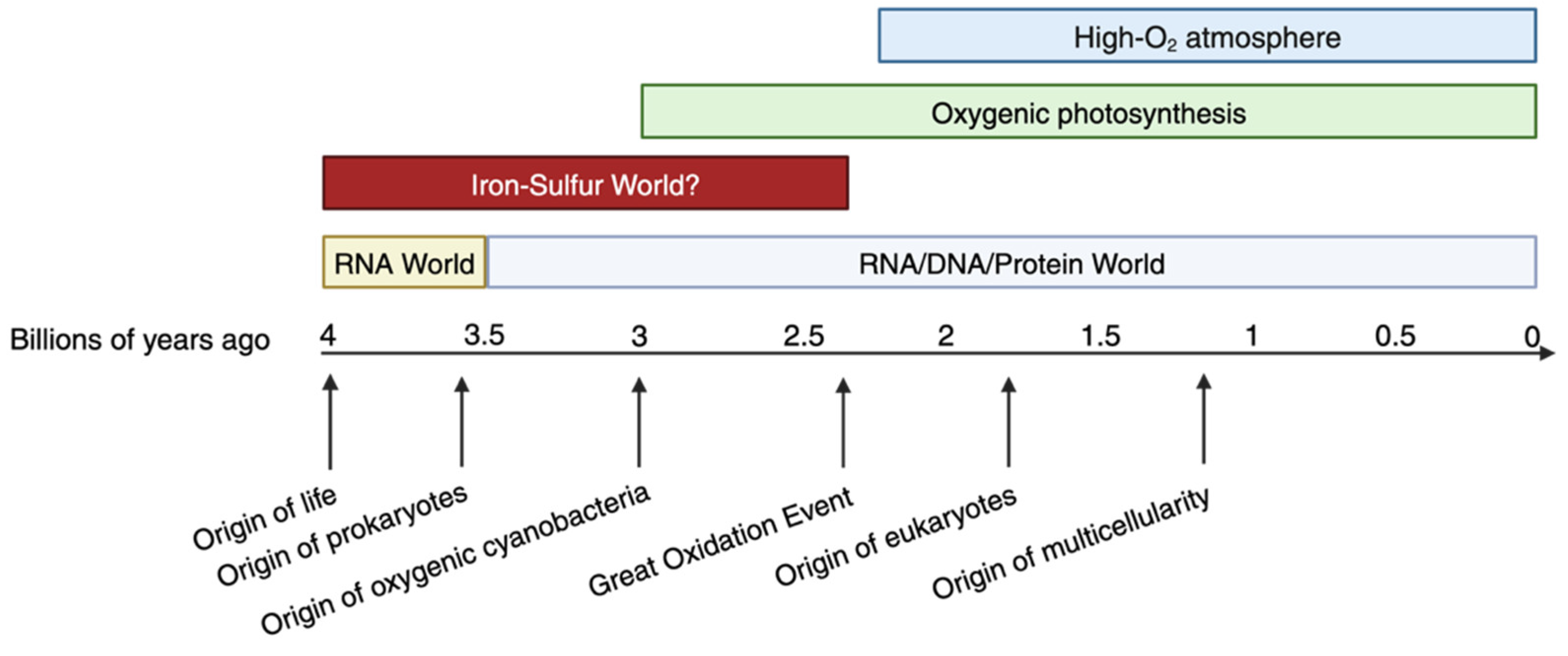

1. In the Beginning: The Prehistoric Chemical Landscape Shaped the Evolution of Biochemical Pathways

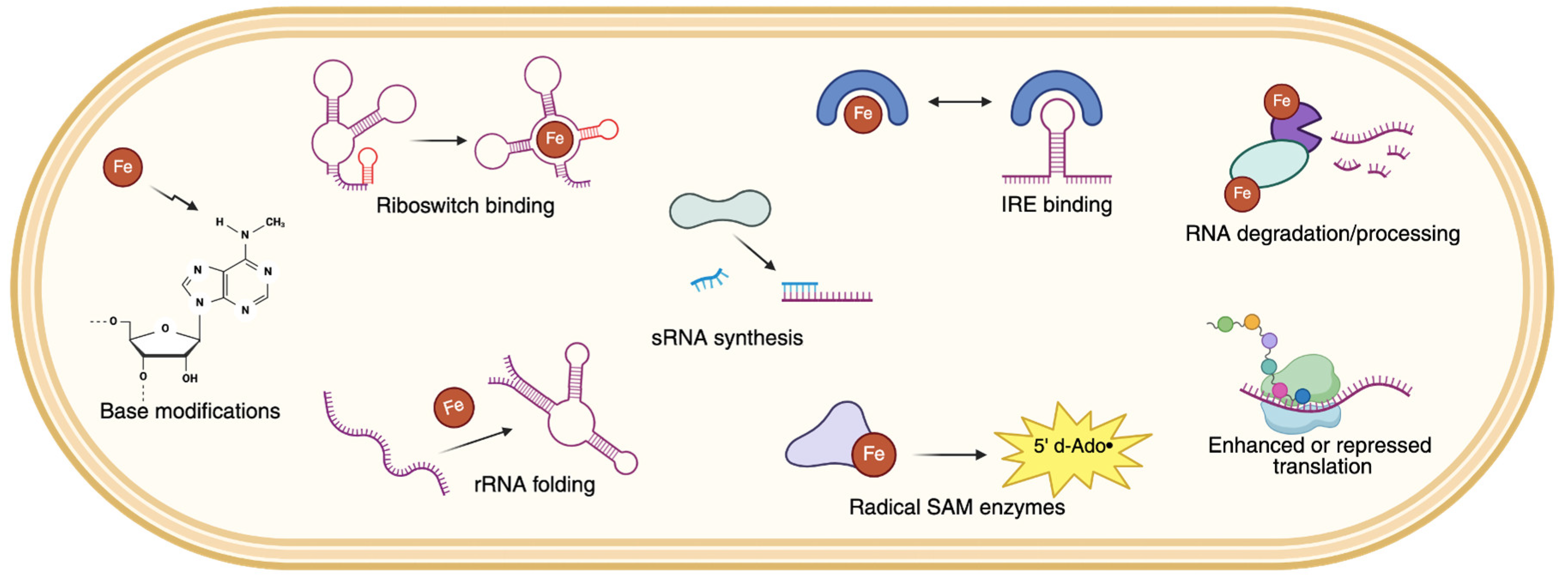

2. Direct Roles of Iron in RNA Cleavage

A Brief Overview of the Machinery That Processes and Degrades Bacterial RNA

PNPase Is a Multifunctional Metal-Binding Enzyme

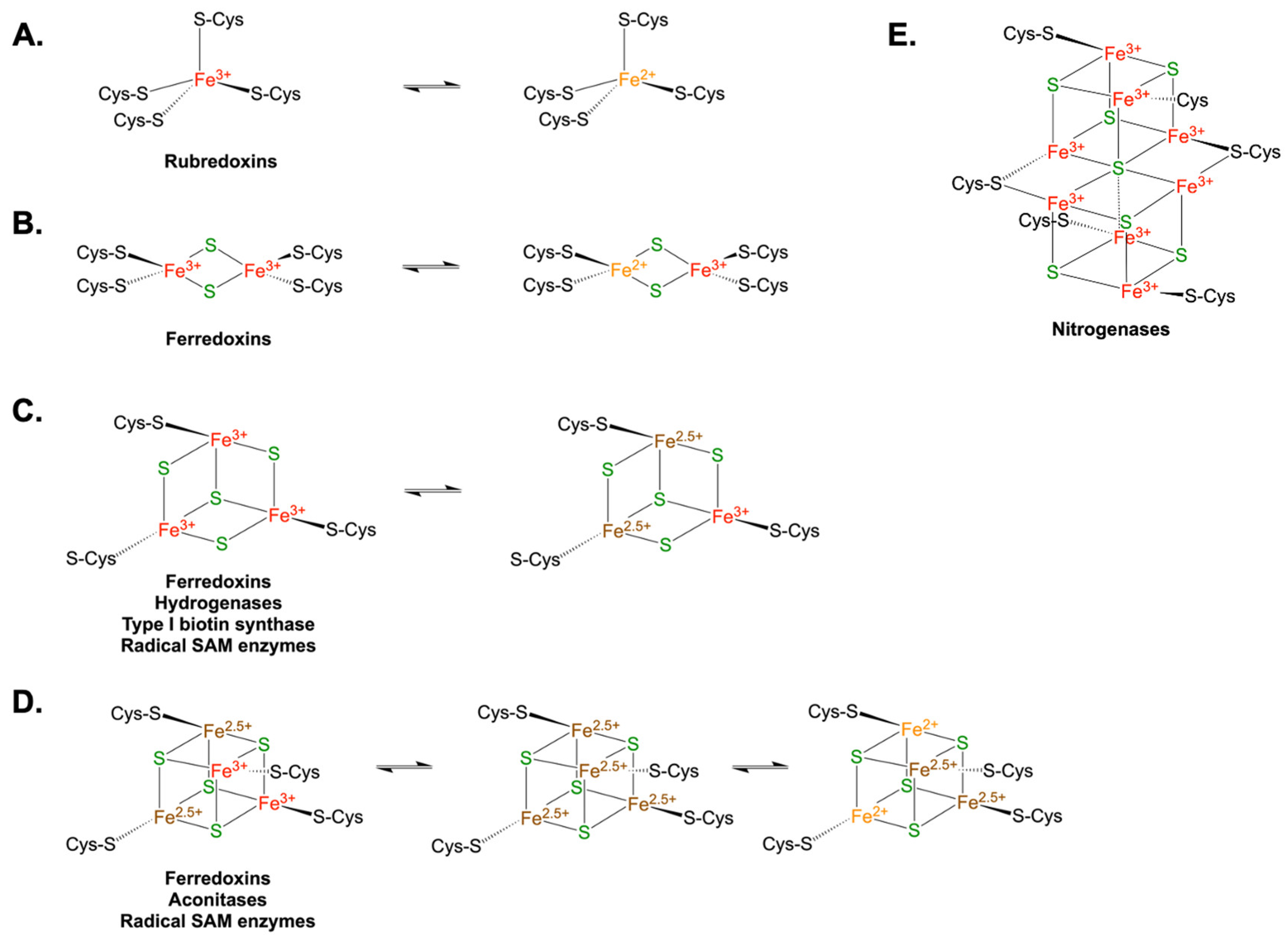

Some Iron-Sulfur Proteins Participate in RNA Processing

Iron-Mediated Degradation of Ribosomal RNAs

3. Iron-Mediated RNA Modifications

A Brief Introduction to Post-Transcriptional RNA Modifications

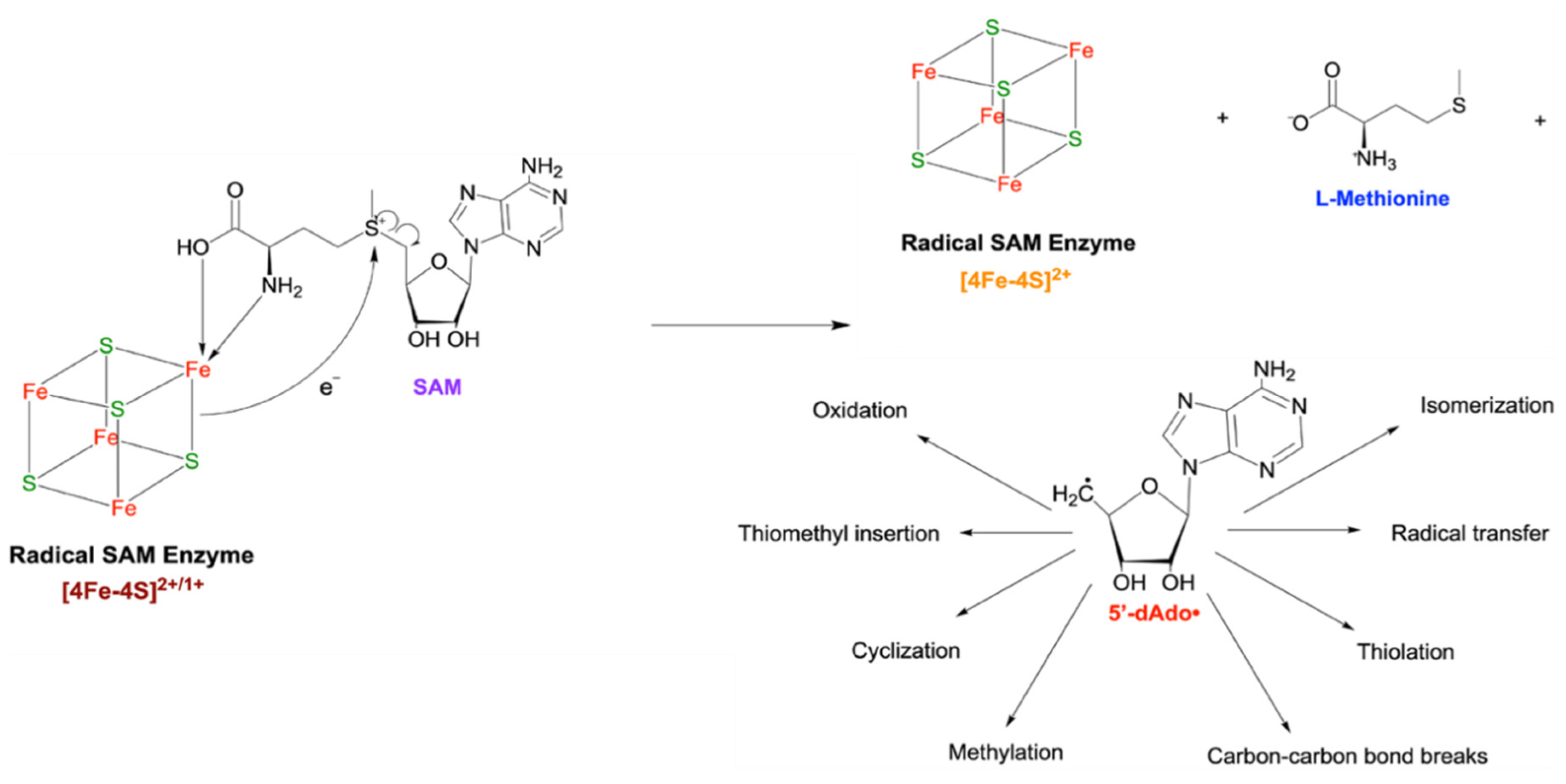

Radical SAM Enzymes Use an Fe-S Cluster to Generate a Radical Intermediate with Widespread Effects

4. Iron-Mediated Regulation of Transcription and mRNA Degradation

Transcript Abundance Is Regulated in Response to Changing Conditions

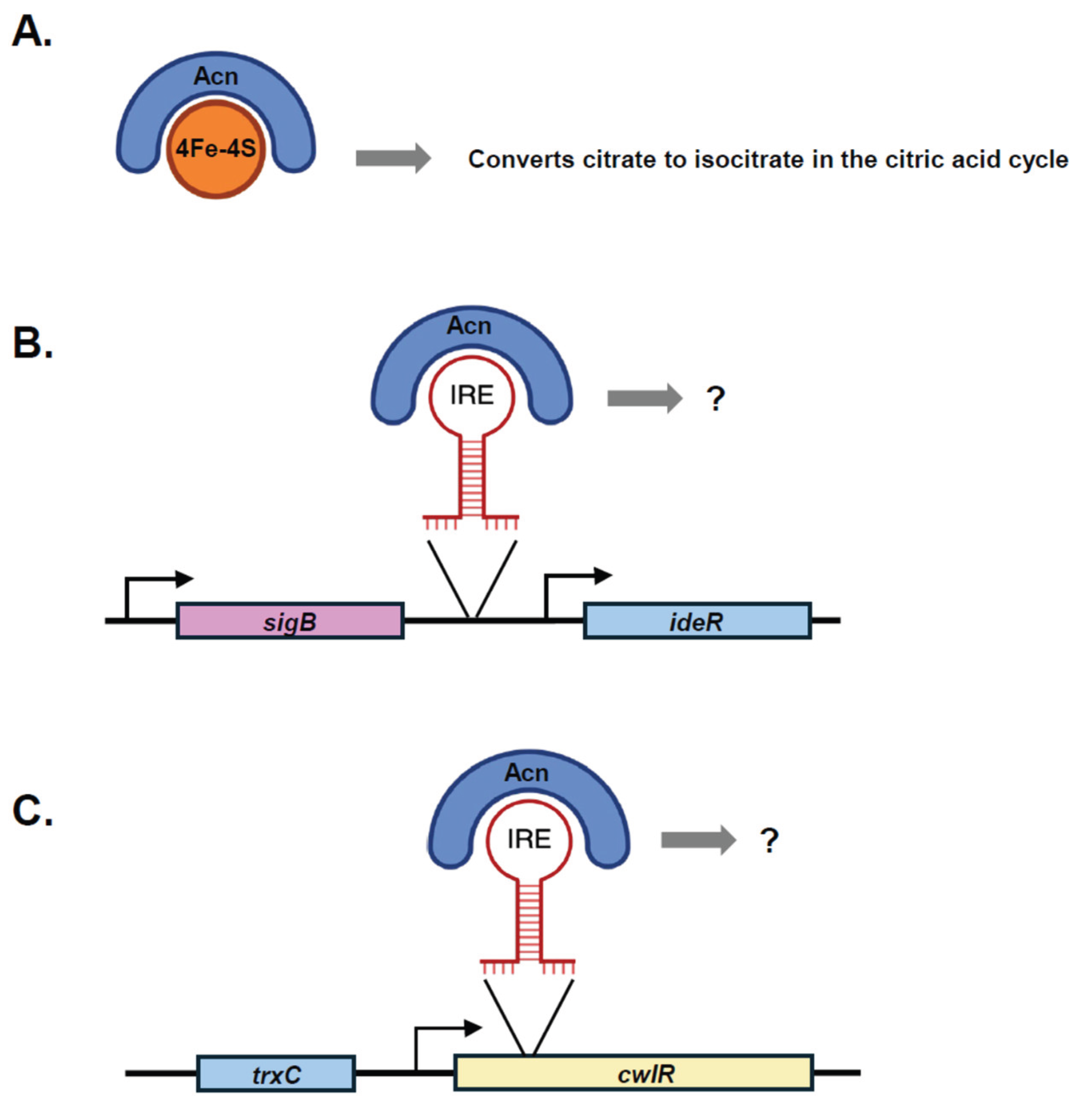

Aconitase and Iron-Response Elements

Iron-Regulated sRNAs

Iron-Regulated Riboswitches

5. From Past to Future

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Holland, H.D. The Oceans; A Possible Source of Iron in Iron-Formations. Econ. Geol. 1973, 68, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C. Some Precambrian banded iron-formations (BIFs) from around the world: Their age, geologic setting, mineralogy, metamorphism, geochemistry, and origins. Am. Miner. 2005, 90, 1473–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, R.M.; Ferry, J.M. Mineral Evolution: Mineralogy in the Fourth Dimension. Elements 2010, 6, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächtershäuser, G. Before enzymes and templates: theory of surface metabolism. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 452–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Benner, S.; Ellington, A.D.; Tauer, A. Modern metabolism as a palimpsest of the RNA world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7054–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, CE. 2007. Epistemological issues in the study of microbial life: alternative terran biospheres? Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 38:847–861.

- Nutman, A.P.; Bennett, V.C.; Friend, C.R.L.; Van Kranendonk, M.J.; Chivas, A.R. Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature 2016, 537, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.C.; Benner, S.A.; Cleland, C.E.; Lineweaver, C.H.; McKay, C.P.; Wolfe-Simon, F. Signatures of a Shadow Biosphere. Astrobiology 2009, 9, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Cech T. 2011. RNA worlds: from life’s origins to diversity in gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Schirrmeister, B.E.; Gugger, M.; Donoghue, P.C.J.; Smith, A. Cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event: evidence from genes and fossils. Palaeontology 2015, 58, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, G.P.; Moore, K.R.; Rangel, L.T.; Payette, J.G.; Momper, L.; Bosak, T. The Archean origin of oxygenic photosynthesis and extant cyanobacterial lineages. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20210675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Lombard, J.; Soule, T.; Dunaj, S.; Wu, S.H.; Wojciechowski, M.F.; Giovannoni, S.J. Timing the Evolutionary Advent of Cyanobacteria and the Later Great Oxidation Event Using Gene Phylogenies of a Sunscreen. mBio 2019, 10, e00561–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen B, Buick R. 1999. Redox state of the Archean atmosphere: Evidence from detrital heavy minerals in ca. 3250–2750 Ma sandstones from the Pilbara Craton, Australia. Geology 27:115–118.

- Anbar AD, Duan Y, Lyons TW, Arnold GL, Kendall B, Creaser RA, Kaufman AJ, Gordon GW, Scott C, Garvin J, Buick R. 2007. A Whiff of Oxygen Before the Great Oxidation Event? Science 317:1903–1906.

- Bachan, A.; Kump, L.R. The rise of oxygen and siderite oxidation during the Lomagundi Event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6562–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, HD. 2002. Volcanic gases, black smokers, and the great oxidation event. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 66:3811–3826.

- Catling, D.C.; Zahnle, K.J.; McKay, C.P. Biogenic Methane, Hydrogen Escape, and the Irreversible Oxidation of Early Earth. Science 2001, 293, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, S.L.; Kump, L.R.; Kasting, J.F. Quantifying the areal extent and dissolved oxygen concentrations of Archean oxygen oases. Chem. Geol. 2013, 362, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel A, Bromberg Y, Falkowski PG, Bhattacharya D. 2014. Evolutionary history of redox metal-binding domains across the tree of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111:7042–7047.

- Aguirre, J.D.; Culotta, V.C. Battles with Iron: Manganese in Oxidative Stress Protection. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13541–13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushizaka, S.; Kuma, K.; Suzuki, K. Effects of Mn and Fe on growth of a coastal marine diatom Talassiosira weissflogii in the presence of precipitated Fe(III) hydroxide and EDTA-Fe(III) complex. Fish. Sci. 2011, 77, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrents, E.; Aloy, P.; Gibert, I.; Rodríguez-Trelles, F. Ribonucleotide Reductases: Divergent Evolution of an Ancient Enzyme. J. Mol. Evol. 2002, 55, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin JE, Imlay JA. 2011. The alternative aerobic ribonucleotide reductase of Escherichia coli, NrdEF, is a manganese-dependent enzyme that enables cell replication during periods of iron starvation. Molecular Microbiology 80:319–334.

- Cotruvo, J.A.; Stubbe, J. Class I Ribonucleotide Reductases: Metallocofactor Assembly and Repair In Vitro and In Vivo. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 733–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjem, A.; Varghese, S.; Imlay, J.A. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe-Simon F, Starovoytov V, Reinfelder JR, Schofield O, Falkowski PG. 2006. Localization and role of manganese superoxide dismutase in a marine diatom. Plant Physiology 142:1701–1709.

- Athavale, S.S.; Petrov, A.S.; Hsiao, C.; Watkins, D.; Prickett, C.D.; Gossett, J.J.; Lie, L.; Bowman, J.C.; O'NEill, E.; Bernier, C.R.; et al. RNA Folding and Catalysis Mediated by Iron (II). PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e38024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, B.E.; de Vos, J.M.; Antonelli, A.; Bagheri, H.C. Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockford, P.W.; Kunzmann, M.; Bekker, A.; Hayles, J.; Bao, H.; Halverson, G.P.; Peng, Y.; Bui, T.H.; Cox, G.M.; Gibson, T.M.; et al. Claypool continued: Extending the isotopic record of sedimentary sulfate. Chem. Geol. 2019, 513, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockford, P.W.; Bar On, Y.M.; Ward, L.M.; Milo, R.; Halevy, I. The geologic history of primary productivity. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 4741–4750.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll AH, Nowak MA. 2017. The timetable of evolution. Science Advances 3:e1603076.

- Bray MS, Lenz TK, Haynes JW, Bowman JC, Petrov AS, Reddi AR, Hud NV, Williams LD, Glass JB. 2018. Multiple prebiotic metals mediate translation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115:12164–12169.

- Prody, G.A.; Bakos, J.T.; Buzayan, J.M.; Schneider, I.R.; Bruening, G. Autolytic Processing of Dimeric Plant Virus Satellite RNA. Science 1986, 231, 1577–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammann, C.; Luptak, A.; Perreault, J.; de la Peña, M. The ubiquitous hammerhead ribozyme. RNA 2012, 18, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athavale, S.S.; Petrov, A.S.; Hsiao, C.; Watkins, D.; Prickett, C.D.; Gossett, J.J.; Lie, L.; Bowman, J.C.; O'NEill, E.; Bernier, C.R.; et al. RNA Folding and Catalysis Mediated by Iron (II). PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e38024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Chou, I.-C.; Okafor, C.D.; Bowman, J.C.; O'Neill, E.B.; Athavale, S.S.; Petrov, A.S.; Hud, N.V.; Wartell, R.M.; Harvey, S.C.; et al. RNA with iron(II) as a cofactor catalyses electron transfer. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Golyshina, O.V.; Beloqui, A.; Böttger, L.H.; Andreu, J.M.; Polaina, J.; De Lacey, A.L.; Trautwein, A.X.; Timmis, K.N.; Golyshin, P.N. A purple acidophilic di-ferric DNA ligase from Ferroplasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 8878–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, C.D.; Lanier, K.A.; Petrov, A.S.; Athavale, S.S.; Bowman, J.C.; Hud, N.V.; Williams, L.D. Iron mediates catalysis of nucleic acid processing enzymes: support for Fe(II) as a cofactor before the great oxidation event. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 3634–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, H.; Williams, R.J.P. Order of Stability of Metal Complexes. Nature 1948, 162, 746–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster AW, Young TR, Chivers PT, Robinson NJ. 2022. Protein metalation in biology. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 66:102095.

- Xu J, Cotruvo JA. 2022. Iron-responsive riboswitches. Current opinion in chemical biology 68:102135.

- Andrews, S.C.; Robinson, A.K.; Rodríguez-Quiñones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Blanco, D.A.; Shell, S.S. Regulation of mRNA Stability During Bacterial Stress Responses. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Blanco, D.A.; Zhou, Y.; Zamalloa, L.G.; Antonelli, T.; Shell, S.S.; Barkan, D. mRNA Degradation Rates Are Coupled to Metabolic Status in Mycobacterium smegmatis. mBio 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Blanco, D.A.; Shell, S.S. Regulation of mRNA Stability During Bacterial Stress Responses. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpousis, A.J.; Van Houwe, G.; Ehretsmann, C.; Krisch, H.M. Copurification of E. coli RNAase E and PNPase: Evidence for a specific association between two enzymes important in RNA processing and degradation. Cell 1994, 76, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpousis, A.J. The RNA Degradosome of Escherichia coli: An mRNA-Degrading Machine Assembled on RNase E. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 61, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcaida, M.J.; DePristo, M.A.; Chandran, V.; Carpousis, A.J.; Luisi, B.F. The RNA degradosome: life in the fast lane of adaptive molecular evolution. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Mizota, T.; Inada, T.; Aiba, H. Enolase in the RNA degradosome plays a crucial role in the rapid decay of glucose transporter mRNA in the response to phosphosugar stress in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, S.W.; Chan, V.S.Y.; Broadhurst, R.W.; Luisi, B.F. An RNA degradosome assembly in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 39, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Arranz, A.; Galtier, E.; El Mortaji, L.; Turlin, E.; Ershov, D.; De Reuse, H.; Charpentier, E. The RNase J-Based RNA Degradosome Is Compartmentalized in the Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, A.; Martínez, J.L. Genome-wide analysis shows that RNase G plays a global role in the stability of mRNAs in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pandit, S.; Deutscher, M.P. RNase G (CafA protein) and RNase E are both required for the 5′ maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2878–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, S.; Condon, C.; Storz, G.; Papenfort, K. RNases and Helicases in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aït-Bara, S.; Carpousis, A.J.; Quentin, Y. RNase E in the γ-Proteobacteria: conservation of intrinsically disordered noncatalytic region and molecular evolution of microdomains. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 290, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada-Arranz, A.; Galtier, E.; El Mortaji, L.; Turlin, E.; Ershov, D.; De Reuse, H.; Charpentier, E. The RNase J-Based RNA Degradosome Is Compartmentalized in the Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu T-Y, Tsai S-H, Chen J-W, Wang Y-C, Hu S-T, Chen Y-Y. 2021. Mab_3083c Is a Homologue of RNase J and Plays a Role in Colony Morphotype, Aggregation, and Sliding Motility of Mycobacterium abscessus. Microorganisms 9:676.

- Aït-Bara, S.; Carpousis, A.J. RNA degradosomes in bacteria and chloroplasts: classification, distribution and evolution of RNase E homologs. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 97, 1021–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, T.; Wachi, M. Corynebacterium glutamicum RNase E/G-type endoribonuclease encoded by NCgl2281 is involved in the 5′ maturation of 5S rRNA. Arch. Microbiol. 2011, 194, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverniti V, Forti F, Ghisotti D, Putzer H. 2011. Mycobacterium smegmatis RNase J is a 5’-3’ exo-/endoribonuclease and both RNase J and RNase E are involved in ribosomal RNA maturation. Molecular microbiology 82:1260–1276.

- Płociński, P.; Macios, M.; Houghton, J.; Niemiec, E.; Płocińska, R.; Brzostek, A.; Słomka, M.; Dziadek, J.; Young, D.; Dziembowski, A. Proteomic and transcriptomic experiments reveal an essential role of RNA degradosome complexes in shaping the transcriptome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5892–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Sun H, Rapiejko AR, Vargas-Blanco DA, Martini MC, Chase MR, Joubran SR, Davis AB, Dainis JP, Kelly JM, Ioerger TR, Roberts LA, Fortune SM, Shell SS. 2023. Mycobacterial RNase E cleaves with a distinct sequence preference and controls the degradation rates of most Mycolicibacterium smegmatis mRNAs. Journal of Biological Chemistry 299:105312.

- Jaiswal, L.K.; Singh, R.K.; Nayak, T.; Kakkar, A.; Kandwal, G.; Singh, V.S.; Gupta, A. A comparative analysis of mycobacterial ribonucleases: Towards a therapeutic novel drug target. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2024, 123, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEJADA-ARRANZ A, de CRECY-LAGARD V, DE REUSE H. 2020. Bacterial RNA degradosomes. Trends Biochem Sci 45:42–57.

- Martini, B.A.; Grigorov, A.S.; Skvortsova, Y.V.; Bychenko, O.S.; Salina, E.G.; Azhikina, T.L. Small RNA MTS1338 Configures a Stress Resistance Signature in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnik-Habrink, M.; Pförtner, H.; Rempeters, L.; Pietack, N.; Herzberg, C.; Stülke, J. The RNA degradosome in Bacillus subtilis: identification of CshA as the major RNA helicase in the multiprotein complex. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 77, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq IU, Müller P, Brantl S. 2024. A comprehensive study of the interactions in the B. subtilis degradosome with special emphasis on the role of the small proteins SR1P and SR7P. Molecular microbiology 121:40–52.

- Commichau FM, Rothe FM, Herzberg C, Wagner E, Hellwig D, Lehnik-Habrink M, Hammer E, Völker U, Stülke J. 2009. Novel activities of glycolytic enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: interactions with essential proteins involved in mRNA processing. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 8:1350–1360.

- Roux, C.M.; DeMuth, J.P.; Dunman, P.M. Characterization of Components of the Staphylococcus aureus mRNA Degradosome Holoenzyme-Like Complex. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 5520–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, S.; Pellegrini, O.; Zig, L.; Labas, V.; Vinh, J.; Bréchemmier-Baey, D.; Putzer, H. Ribonucleases J1 and J2: two novel endoribonucleases in B.subtilis with functional homology to E.coli RNase E. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2141–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugrysheva, J.V.; Scott, J.R. The ribonucleases J1 and J2 are essential for growth and have independent roles in mRNA decay in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 75, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan AJ, Redko Y, Murphy LM, Grossmann JG, Yates D, Garman E, Ilag LL, Robinson CV, Symmons MartynF, McDowall KJ, Luisi BF. 2005. “Zn-Link”: A Metal-Sharing Interface that Organizes the Quaternary Structure and Catalytic Site of the Endoribonuclease, RNase E. Biochemistry 44:4667–4675.

- Mardle, C.E.; Shakespeare, T.J.; Butt, L.E.; Goddard, L.R.; Gowers, D.M.; Atkins, H.S.; Vincent, H.A.; Callaghan, A.J. A structural and biochemical comparison of Ribonuclease E homologues from pathogenic bacteria highlights species-specific properties. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K.J.; Zong, J.; Mackie, G.A.; Gourse, R.L. Altering the Divalent Metal Ion Preference of RNase E. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 197, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbabian, K.; Jamalli, A.; Zig, L.; Putzer, H. RNase Y, a novel endoribonuclease, initiates riboswitch turnover in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3523–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deana, A.; Belasco, J.G. The function of RNase G in Escherichia coli is constrained by its amino and carboxyl termini. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrey, S.M.; Blech, M.; Riffell, J.L.; Hankins, J.S.; Stickney, L.M.; Diver, M.; Hsu, Y.-H.R.; Kunanithy, V.; Mackie, G.A. Substrate Binding and Active Site Residues in RNases E and G. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 31843–31850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, A.; Sheffy-Levin, S.; Glaser, F.; Schuster, G. The RNase E/G-type endoribonuclease of higher plants is located in the chloroplast and cleaves RNA similarly to the E. coli enzyme. RNA 2008, 14, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Nadig, S.; Patel, T.; Gopal, B. Structural and biochemical characteristics of two Staphylococcus epidermidis RNase J paralogs RNase J1 and RNase J2. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16863–16876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblar, M.; Arraiano, C.M. A single mutation in Escherichia coli ribonuclease II inactivates the enzyme without affecting RNA binding. FEBS J. 2004, 272, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Steitz, T.; A Steitz, J. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 6498–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Vincent, H.A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Deutscher, M.P.; Malhotra, A. Structural Basis for Processivity and Single-Strand Specificity of RNase II. Mol. Cell 2006, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, H.A.; Deutscher, M.P. The Roles of Individual Domains of RNase R in Substrate Binding and Exoribonuclease Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.-F.; Deutscher, M.P. An Important Role for RNase R in mRNA Decay. Mol. Cell 2005, 17, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano MG, Engl C. 2021. The lifecycle of ribosomal RNA in bacteria. RNA Damage and Repair 27–51.

- Apirion, D.; Gegenheimer, P. Processing of bacterial RNA. FEBS Lett. 1981, 125, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, MP. 2009. Maturation and degradation of ribosomal RNA in bacteria. Progress in molecular biology and translational science 85:369–391.

- Loughney, K.; Lund, E.; Dahlberg, J.E. Ribosomal RNA precursors ofBacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983, 11, 6709–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pandit, S.; Deutscher, M.P. RNase G (CafA protein) and RNase E are both required for the 5′ maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2878–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachi M, Umitsuki G, Shimizu M, Takada A, Nagai K. 1999. Escherichia coli cafA Gene Encodes a Novel RNase, Designated as RNase G, Involved in Processing of the 5′ End of 16S rRNA. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 259:483–488.

- Li, Z.; Deutscher, M.P. The tRNA processing enzyme RNase T is essential for maturation of 5S RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6883–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pandit, S.; Deutscher, M.P. Maturation of 23S ribosomal RNA requires the exoribonuclease RNase T. RNA 1999, 5, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Deutscher, M.P.; Lovett, S.T. Exoribonucleases and Endoribonucleases. EcoSal Plus 2004, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.C.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, H.; Shell, S.S. Defining the Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Landscapes of Mycobacterium smegmatis in Aerobic Growth and Hypoxia. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, A.W. Ribonuclease III mechanisms of double-stranded RNA cleavage. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2013, 5, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Campbell, F.; Cassano, A.G.; E Anderson, V.; E Harris, M. Pre-steady-state and stopped-flow fluorescence analysis of Escherichia coli ribonuclease III: insights into mechanism and conformational changes associated with binding and catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 317, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, M.; van de Weerd, R.; Brouwer, F.C.; Roviello, G.N.; Lacroix, R.; Sparrius, M.; Stempvoort, G.v.D.B.-V.; Maaskant, J.J.; van der Sar, A.M.; Appelmelk, B.J.; et al. Structure and Function of RNase AS, a Polyadenylate-Specific Exoribonuclease Affecting Mycobacterial Virulence In Vivo. Structure 2014, 22, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo Y, Zheng H, Wang Y, Chruszcz M, Cymborowski M, Skarina T, Savchenko A, Malhotra A, Minor W. 2007. Crystal Structure of RNase T, an exoribonuclease involved in tRNA maturation and end-turnover. Structure 15:417–428.

- Badhwar, P.; Khan, S.H.; Taneja, B. Three-dimensional structure of a mycobacterial oligoribonuclease reveals a unique C-terminal tail that stabilizes the homodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechold, U.; Fang, G.; Ngo, S.; Ogryzko, V.; Danchin, A. YtqI from Bacillus subtilis has both oligoribonuclease and pAp-phosphatase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 4552–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Deutscher, M.P. RNase E plays an essential role in the maturation of Escherichia coli tRNA precursors. RNA 2002, 8, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Deutscher, M.P. Maturation Pathways for E. coli tRNA Precursors: A Random Multienzyme Process In Vivo. Cell 1996, 86, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Oussenko, I.A.; Pellegrini, O.; Bechhofer, D.H.; Condon, C. Ribonuclease PH plays a major role in the exonucleolytic maturation of CCA-containing tRNA precursors in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3636–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, L.S.; Kadziola, A.; Jensen, K.F.; Larsen, S. Crystal structure of the phosphorolytic exoribonuclease RNase PH from Bacillus subtilis and implications for its quaternary structure and tRNA binding. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, J.A.; Kurz, J.C.; Fierke, C.A. Magnesium Ions Are Required by Bacillus subtilis Ribonuclease P RNA for both Binding and Cleaving Precursor tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 10493–10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantsev, A.V.; Krivenko, A.A.; Pace, N.R. Mapping metal-binding sites in the catalytic domain of bacterial RNase P RNA. RNA 2008, 15, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudny, H.; Zaniewski, R.; Deutscher, M. Escherichia coli RNase D. Catalytic properties and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 5633–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redko, Y.; de la Sierra-Gallay, I.L.; Condon, C. When all's zed and done: the structure and function of RNase Z in prokaryotes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty BK, Kushner SR. 2000. Polynucleotide phosphorylase functions both as a 3’ right-arrow 5’ exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97:11966–11971.

- Mohanty BK, Kushner SR. 2000. Polynucleotide phosphorylase, RNase II and RNase E play different roles in the in vivo modulation of polyadenylation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 36:982–994.

- Jarrige, A.-C.; Bréchemier-Baey, D.; Mathy, N.; Duché, O.; Portier, C. Mutational Analysis of Polynucleotide Phosphorylase from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 321, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unciuleac, M.-C.; Shuman, S. Discrimination of RNA from DNA by Polynucleotide Phosphorylase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 6702–6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unciuleac, M.-C.; Shuman, S. Distinctive Effects of Domain Deletions on the Manganese-Dependent DNA Polymerase and DNA Phosphorylase Activities of Mycobacterium smegmatis Polynucleotide Phosphorylase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2967–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmohamed, S.; Vaidialingam, B.; Callaghan, A.J.; Luisi, B.F. Crystal Structure of Escherichia coli Polynucleotide Phosphorylase Core Bound to RNase E, RNA and Manganese: Implications for Catalytic Mechanism and RNA Degradosome Assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 389, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, L.; Yin, D.; Feng, J.; Li, L.; Guo, X. Single-exonuclease nanocircuits reveal the RNA degradation dynamics of PNPase and demonstrate potential for RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syson K, Tomlinson C, Chapados BR, Sayers JR, Tainer JA, Williams NH, Grasby JA. 2008. Three metal ions participate in the reaction catalyzed by T5 flap endonuclease. The Journal of biological chemistry 283:28741–28746.

- Ju, T.; Goldsmith, R.B.; Chai, S.C.; Maroney, M.J.; Pochapsky, S.S.; Pochapsky, T.C. One Protein, Two Enzymes Revisited: A Structural Entropy Switch Interconverts the Two Isoforms of Acireductone Dioxygenase. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.C.; Ju, T.; Dang, M.; Goldsmith, R.B.; Maroney, M.J.; Pochapsky, T.C. Characterization of Metal Binding in the Active Sites of Acireductone Dioxygenase Isoforms from Klebsiella ATCC 8724. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 2428–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, A.R.; Pochapsky, T.C.; Petsko, G.A.; Ringe, D. Dual chemistry catalyzed by human acireductone dioxygenase. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2017, 30, 109–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, A.R.; Pochapsky, T.C.; Ringe, D. The Metal Drives the Chemistry: Dual Functions of Acireductone Dioxygenase. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10474–10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, A.R.; Wagenpfeil, K.; Pochapsky, T.C.; Petsko, G.A.; Ringe, D. Metal-Dependent Function of a Mammalian Acireductone Dioxygenase. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Garber, A.; Ryan, J.; Deshpande, A.; Ringe, D.; Pochapsky, T.C. A Model for the Solution Structure of Human Fe(II)-Bound Acireductone Dioxygenase and Interactions with the Regulatory Domain of Matrix Metalloproteinase I (MMP-I). Biochemistry 2020, 59, 4238–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pochapsky, T.C. Human Acireductone Dioxygenase (HsARD), Cancer and Human Health: Black Hat, White Hat or Gray? Inorganics 2019, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłaczewska, A.; Kot, E.; Amaya, J.A.; Makris, T.M.; Zając, M.; Korecki, J.; Chumakov, A.; Trzewik, B.; Kędracka-Krok, S.; Minor, W.; et al. On the Structure and Reaction Mechanism of Human Acireductone Dioxygenase. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2017, 24, 5225–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beljanksi, M. 1995. De novo synthesis of DNA-like molecules by polynucleotide phosphorylase in vitro. Journal of Molecular Evolution 493–499.

- Cardenas, P.P.; Carzaniga, T.; Zangrossi, S.; Briani, F.; Garcia-Tirado, E.; Dehò, G.; Alonso, J.C. Polynucleotide phosphorylase exonuclease and polymerase activities on single-stranded DNA ends are modulated by RecN, SsbA and RecA proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9250–9261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraiano, C.M.; Andrade, J.M.; Domingues, S.; Guinote, I.B.; Malecki, M.; Matos, R.G.; Moreira, R.N.; Pobre, V.; Reis, F.P.; Saramago, M.; et al. The critical role of RNA processing and degradation in the control of gene expression. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 883–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Fisher, P.B. Polynucleotide phosphorylase: An evolutionary conserved gene with an expanding repertoire of functions. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 112, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateswara Rao P, Holm RH. 2004. Synthetic Analogues of the Active Sites of Iron−Sulfur Proteins. Chem Rev 104:527–560.

- Vallières, C.; Benoit, O.; Guittet, O.; Huang, M.-E.; Lepoivre, M.; Golinelli-Cohen, M.-P.; Vernis, L. Iron-sulfur protein odyssey: exploring their cluster functional versatility and challenging identification. Metallomics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao W, Gurubasavaraj PM, Holland PL. 2014. All-Ferrous Iron–Sulfur Clusters, p. 1–37. In Rabinovich, D (ed.), Molecular Design in Inorganic Biochemistry. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Beinert H, Holm RH, Münck E. 1997. Iron-sulfur clusters: nature’s modular, multipurpose structures. Science 277:653–659.

- Lee, W.; Brune, D.; Lobrutto, R.; Blankenship, R. Isolation, Characterization, and Primary Structure of Rubredoxin from the Photosynthetic Bacterium, Heliobacillus mobilis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 318, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.L.; Shaw, L. A Comprehensive Phylogenetic Analysis of Rieske and Rieske-Type Iron-Sulfur Proteins. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2001, 33, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, T.A.; Dailey, H.A. Identification of [2Fe-2S] Clusters in Microbial Ferrochelatases. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 2460–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuta Y, Horio T, Takahashi Y, Fukuyama K. 2001. Crystal Structure of Escherichia coli Fdx, an Adrenodoxin-Type Ferredoxin Involved in the Assembly of Iron−Sulfur Clusters. Biochemistry 40:11007–11012.

- Escalettes, F.; Florentin, D.; Bui, B.T.S.; Lesage, D.; Marquet, A. Biotin Synthase Mechanism: Evidence for Hydrogen Transfer from the Substrate into Deoxyadenosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 3571–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, J.C.; Lennox-Hvenekilde, D.; Myling-Petersen, N.; Salomonsen, B.; Verkleij, G.; Acevedo-Rocha, C.G.; Caddell, B.; Gronenberg, L.S.; Almo, S.C.; Sommer, M.O.A.; et al. Discovery of a Biotin Synthase That Utilizes an Auxiliary 4Fe–5S Cluster for Sulfur Insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.W.; Eccleston, E.; Howard, J.B. Iron-sulfur clusters of hydrogenase I and hydrogenase II of Clostridium pasteurianum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 4932–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinert H, Kennedy MC, Stout CD. 1996. Aconitase as Iron−Sulfur Protein, Enzyme, and Iron-Regulatory Protein. Chem Rev 96:2335–2374.

- Smith, A.T.; Linkous, R.O.; Max, N.J.; Sestok, A.E.; Szalai, V.A.; Chacón, K.N. The FeoC [4Fe–4S] Cluster Is Redox-Active and Rapidly Oxygen-Sensitive. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 4935–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keable, S.M.; Zadvornyy, O.A.; Johnson, L.E.; Ginovska, B.; Rasmussen, A.J.; Danyal, K.; Eilers, B.J.; Prussia, G.A.; LeVan, A.X.; Raugei, S.; et al. Structural characterization of the P1+ intermediate state of the P-cluster of nitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 9629–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupnik K, Hu Y, Lee CC, Wiig JA, Ribbe MW, Hales BJ. 2012. P+ State of Nitrogenase P-Cluster Exhibits Electronic Structure of a [Fe4S4]+ Cluster. J Am Chem Soc 134:13749–13754.

- Osterloh, F.; Sanakis, Y.; Staples, R.J.; Münck, E.; Holm, R.H. A Molybdenum-Iron-Sulfur Cluster Containing Structural Elements Relevant to the P-Cluster of Nitrogenase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1999, 38, 2066–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Assembly and Transfer of Iron–Sulfur Clusters in the Plastid. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazzon, J.; Dean, D.R. Formation of iron–sulfur clusters in bacteria: an emerging field in bioinorganic chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003, 7, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohki Y, Tanifuji K, Yamada N, Cramer RE, Tatsumi K. 2012. Formation of a nitrogenase P-cluster [Fe8S7] core via reductive fusion of two all-ferric [Fe4S4] clusters. Chem Asian J 7:2222–2224.

- Fontecave, M.; Ollagnier-De-Choudens, S. Iron–sulfur cluster biosynthesis in bacteria: Mechanisms of cluster assembly and transfer. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 474, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche B, Aussel L, Ezraty B, Mandin P, Py B, Barras F. 2013. Iron/sulfur proteins biogenesis in prokaryotes: Formation, regulation and diversity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1827:455–469.

- Tripathi, A.; Anand, K.; Das, M.; O’nIel, R.A.; S, S.P.; Thakur, C.; L. , R.R.R.; Rajmani, R.S.; Chandra, N.; Laxman, S.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires SufT for Fe-S cluster maturation, metabolism, and survival in vivo. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidese, R.; Mihara, H.; Kurihara, T.; Esaki, N. Global Identification of Genes Affecting Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis and Iron Homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Rees DC. 1992. Crystallographic structure and functional implications of the nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein from azotobacter vinelandii. Nature 360:553–560.

- White, M.F.; Dillingham, M.S. Iron–sulphur clusters in nucleic acid processing enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012, 22, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinge, S.; Hirst, J.; Maman, J.D.; Krude, T.; Pellegrini, L. An iron-sulfur domain of the eukaryotic primase is essential for RNA primer synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussenko IA, Abe T, Ujiie H, Muto A, Bechhofer DH. 2005. Participation of 3’-to-5’ exoribonucleases in the turnover of Bacillus subtilis mRNA. J Bacteriol 187:2758–2767.

- Gimpel M, Brantl S. 2016. Dual-function sRNA encoded peptide SR1P modulates moonlighting activity of B. subtilis GapA. RNA Biol 13:916–926.

- Ul Haq I, Brantl S. 2021. Moonlighting in Bacillus subtilis: The Small Proteins SR1P and SR7P Regulate the Moonlighting Activity of Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase A (GapA) and Enolase in RNA Degradation. Microorganisms 9:1046.

- Dubnau, E.; DeSantis, M.; Dubnau, D.; Babitzke, P. Formation of a stable RNase Y-RicT (YaaT) complex requires RicA (YmcA) and RicF (YlbF). mBio 2023, 14, e0126923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner AW, Carabetta VJ, Martinie RJ, Mashruwala AA, Boyd JM, Krebs C, Dubnau D. 2017. The RicAFT (YmcA-YlbF-YaaT) complex carries two [4Fe-4S]2+ clusters and may respond to redox changes. Molecular Microbiology 104:837–850.

- DeLoughery, A.; Lalanne, J.-B.; Losick, R.; Li, G.-W. Maturation of polycistronic mRNAs by the endoribonuclease RNase Y and its associated Y-complex in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 201803283–E5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei-Danso F, Khaja FT, Desantis M, Jeffrey PD, Dubnau E, Demeler B, Neiditch MB, Dubnau D. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tortosa P, Albano M, Dubnau D. 2000. Characterization of ylbF, a new gene involved in competence development and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular Microbiology 35:1110–1119.

- Hosoya S, Asai K, Ogasawara N, Takeuchi M, Sato T. 2002. Mutation in yaaT leads to significant inhibition of phosphorelay during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Journal of Bacteriology 184:5545–5553.

- Branda, S.S.; González-Pastor, J.E.; Dervyn, E.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Losick, R.; Kolter, R. Genes Involved in Formation of Structured Multicellular Communities by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 3970–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guth-Metzler, R.; Bray, M.S.; Frenkel-Pinter, M.; Suttapitugsakul, S.; Montllor-Albalate, C.; Bowman, J.C.; Wu, R.; Reddi, A.R.; Okafor, C.D.; Glass, J.B.; et al. Cutting in-line with iron: ribosomal function and non-oxidative RNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8663–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinskie, J.A.; Ghosh, A.; Trainor, B.M.; Shedlovskiy, D.; Pestov, D.G.; Shcherbik, N. Iron-dependent cleavage of ribosomal RNA during oxidative stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 14237–14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, D.G.; Kovalev, N.; McKenzie, E.R.; Pestov, D.G.; Shcherbik, N. Iron-mediated degradation of ribosomes under oxidative stress is attenuated by manganese. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17200–17214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjem, A.; Imlay, J.A. Mononuclear Iron Enzymes Are Primary Targets of Hydrogen Peroxide Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 15544–15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, J.M.; Imlay, J.A. Iron enzyme ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase in Escherichia coli is rapidly damaged by hydrogen peroxide but can be protected by manganese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5402–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev N, Gao A, Serganov A. 2019. Noncanonical features and modifications on the 5′-end of bacterial sRNAs and mRNAs. WIREs RNA 10:e1509.

- Hudeček, O.; Benoni, R.; Reyes-Gutierrez, P.E.; Culka, M.; Šanderová, H.; Hubálek, M.; Rulíšek, L.; Cvačka, J.; Krásný, L.; Cahová, H. Dinucleoside polyphosphates act as 5′-RNA caps in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier P, Marujo PE. 2013. Polyadenylation and Degradation of RNA in ProkaryotesMadame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. Landes Bioscience.

- Briani, F.; Carzaniga, T.; Dehò, G. Regulation and functions of bacterial PNPase. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 7, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, M.P. Degradation of RNA in bacteria: comparison of mRNA and stable RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, J.A.M.; Sáez, G.T.; Seisdedos, R.T. On the Function of Modified Nucleosides in the RNA World. J. Theor. Biol. 1998, 194, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura S, Suzuki T. 2015. Iron–sulfur proteins responsible for RNA modifications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1853:1272–1283.

- Khodour Y, Kaguni LS, Stiban J. 2019. Iron–sulfur clusters in nucleic acid metabolism: Varying roles of ancient cofactors, p. 225–256. In Enzymes. Academic Press.

- Sofia HJ, Chen G, Hetzler BG, Reyes-Spindola JF, Miller NE. 2001. Radical SAM, a novel protein superfamily linking unresolved steps in familiar biosynthetic pathways with radical mechanisms: functional characterization using new analysis and information visualization methods. Nucleic acids research 29:1097–1106.

- Broderick JB, Duffus BR, Duschene KS, Shepard EM. 2014. Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. Chemical Reviews 114:4229–4317.

- Fyfe, C.D.; Bernardo-García, N.; Fradale, L.; Grimaldi, S.; Guillot, A.; Brewee, C.; Chavas, L.M.G.; Legrand, P.; Benjdia, A.; Berteau, O. Crystallographic snapshots of a B12-dependent radical SAM methyltransferase. Nature 2022, 602, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauerle, M.R.; Schwalm, E.L.; Booker, S.J. Mechanistic Diversity of Radical S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent Methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 3995–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.C.; Santi, D.V. On the mechanism and inhibition of DNA cytosine methyltransferases. Prog. Clin. Biol. Research. 1985, 198, 119–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kealey, J.; Gu, X.; Santi, D. Enzymatic mechanism of tRNA (m5U54)methyltransferase. Biochimie 1994, 76, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Saleh, L.; Anton, B.P.; Madinger, C.L.; Benner, J.S.; Iwig, D.F.; Roberts, R.J.; Krebs, C.; Booker, S.J. Characterization of RimO, a New Member of the Methylthiotransferase Subclass of the Radical SAM Superfamily. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 10162–10174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández HL, Pierrel F, Elleingand E, García-Serres R, Huynh BH, Johnson MK, Fontecave M, Atta M. 2007. MiaB, a bifunctional radical-S-adenosylmethionine enzyme involved in the thiolation and methylation of tRNA, contains two essential [4Fe-4S] clusters. Biochemistry 46:5140–5147.

- Arragain, S.; Handelman, S.K.; Forouhar, F.; Wei, F.-Y.; Tomizawa, K.; Hunt, J.F.; Douki, T.; Fontecave, M.; Mulliez, E.; Atta, M. Identification of Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Methylthiotransferase for Biosynthesis of 2-Methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28425–28433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arragain, S.; Garcia-Serres, R.; Blondin, G.; Douki, T.; Clemancey, M.; Latour, J.-M.; Forouhar, F.; Neely, H.; Montelione, G.T.; Hunt, J.F.; et al. Post-translational Modification of Ribosomal Proteins: Structural and Functional Characterization of Rimo from Thermotoga Maritima, A Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methylthiotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 5792–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Woldring, R.P.; Román-Meléndez, G.D.; McClain, A.M.; Alzua, B.R.; Marsh, E.N.G. Recent Advances in Radical SAM Enzymology: New Structures and Mechanisms. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiev PV, Golovina AY, Prokhorova IV, Sergeeva OV, Osterman IA, Nesterchuk MV, Burakovsky DE, Bogdanov AA, Dontsova OA. 2011. Modifications of ribosomal RNA: From enzymes to function, p. 97–110. In Ribosomes. Springer, Vienna.

- Polikanov, Y.S.; Melnikov, S.V.; Söll, D.; Steitz, T.A. Structural insights into the role of rRNA modifications in protein synthesis and ribosome assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, M.; Krüger, A.; Ferstl, R.; Kaufmann, A.; Nees, G.; Sigmund, A.; Bathke, B.; Lauterbach, H.; Suter, M.; Dreher, S.; et al. TLR13 Recognizes Bacterial 23 S rRNA Devoid of Erythromycin Resistance–Forming Modification. Science 2012, 337, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Sakai, Y.; Ishiguro, K.; Suzuki, T. Biogenesis and iron-dependency of ribosomal RNA hydroxylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12974–12986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasnacht, M.; Gallo, S.; Sharma, P.; Himmelstoß, M.; A Limbach, P.; Willi, J.; Polacek, N. Dynamic 23S rRNA modification ho5C2501 benefits Escherichia coli under oxidative stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 50, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, S.; Kealey, J.T.; Santi, D.V.; Stroud, R.M. Characterization of the 23 S Ribosomal RNA m5U1939 Methyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 8835–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.T.; Agarwalla, S.; Stroud, R.M. Crystal Structure of RumA, an Iron-Sulfur Cluster Containing E. coli Ribosomal RNA 5-Methyluridine Methyltransferase. Structure 2004, 12, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritts, J.; Zilinskas, E. 2015. Study of methyletransferase RumB in E. coli. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 711–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, S.; Stroud, R.M.; Gaffney, B.J. Redox Reactions of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster in a Ribosomal RNA Methyltransferase, RumA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34123–34129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, PF. The importance of being modified: roles of modified nucleosides and Mg2+ in RNA structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1996, 53, 79–129. [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavičius, J.; Qian, Q.; Durand, J.M.; Hagervall, T.G.; Björk, G.R. Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4863–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipuviene, R.; Qian, Q.; BjörK, G.R. Formation of Thiolated Nucleosides Present in tRNA from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Occurs in Two Principally Distinct Pathways. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigi, N. Biosynthesis and functions of sulfur modifications in tRNA. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- avužić M, Liu Y. 2017. Biosynthesis of sulfur-containing tRNA modifications: a comparison of bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic Pathways. Biomolecules 7.

- Bandarian, V. Radical SAM enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of purine-based natural products. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2012, 1824, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigi, N.; Horitani, M.; Miyauchi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Kuroki, M. An ancient type of MnmA protein is an iron–sulfur cluster-dependent sulfurtransferase for tRNA anticodons. RNA 2019, 26, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrel, F.; Douki, T.; Fontecave, M.; Atta, M. MiaB Protein Is a Bifunctional Radical-S-Adenosylmethionine Enzyme Involved in Thiolation and Methylation of tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47555–47563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esberg B, Leung HCE, Tsui HCT, Bjork GR, Winkler ME. 1999. Identification of the miaB gene, involved in methylthiolation of isopentenylated A37 derivatives in the tRNA of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology 181:7256–7265.

- Li, Q.; Zallot, R.; MacTavish, B.S.; Montoya, A.; Payan, D.J.; Hu, Y.; Gerlt, J.A.; Angerhofer, A.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Bruner, S.D. Epoxyqueuosine Reductase QueH in the Biosynthetic Pathway to tRNA Queuosine Is a Unique Metalloenzyme. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 3152–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Vinyard DJ, Reesbeck ME, Suzuki T, Manakongtreecheep K, Holland PL, Brudvig GW, Söll D. 2016. A [3Fe-4S] cluster is required for tRNA thiolation in archaea and eukaryotes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113:12703–12708.

- Miles, Z.D.; Myers, W.K.; Kincannon, W.M.; Britt, R.D.; Bandarian, V. Biochemical and Spectroscopic Studies of Epoxyqueuosine Reductase: A Novel Iron–Sulfur Cluster- and Cobalamin-Containing Protein Involved in the Biosynthesis of Queuosine. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4927–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, B.; Buck, M.; Humphreys, J.; Griffiths, E. Iron-related modification of bacterial transfer RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981, 9, 2629–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths E, Humphreys J. 1978. Alterations in tRNAs containing 2-methylthio-N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)-adenosine during growth of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in the presence of iron-binding proteins. European Journal of Biochemistry 82:503–513.

- Urbonavičius, J.; Jäger, G.; Björk, G.R. Amino acid residues of the Escherichia coli tRNA(m5U54)methyltransferase (TrmA) critical for stability, covalent binding of tRNA and enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mettert EL, Kiley PJ. 2015. Fe–S proteins that regulate gene expression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1853:1284–1293.

- Crack, J.C.; Green, J.; Thomson, A.J.; Le Brun, N.E. Iron–Sulfur Clusters as Biological Sensors: The Chemistry of Reactions with Molecular Oxygen and Nitric Oxide. Accounts Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3196–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, E.; Bollinger, J.M.; Bradley, T.M.; Walsh, C.T.; Demple, B. Binuclear [2Fe-2S] Clusters in the Escherichia coli SoxR Protein and Role of the Metal Centers in Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 20908–20914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudu P, Weiss B. 1996. SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] transcription factor, is active only in its oxidized form. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93:10094–10098.

- Kobayashi, K.; Fujikawa, M.; Kozawa, T. Oxidative stress sensing by the iron–sulfur cluster in the transcription factor, SoxR. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 133, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiza Beltran D, Wan T, Zhang L. 2024. WhiB-like proteins: Diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1871:119787.

- Saini, V.; Farhana, A.; Steyn, A.J. Mycobacterium tuberculosisWhiB3: A Novel Iron–Sulfur Cluster Protein That Regulates Redox Homeostasis and Virulence. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Crossman, D.K.; Mai, D.; Guidry, L.; Voskuil, M.I.; Renfrow, M.B.; Steyn, A.J.C.; Bishai, W. Mycobacterium tuberculosis WhiB3 Maintains Redox Homeostasis by Regulating Virulence Lipid Anabolism to Modulate Macrophage Response. PLOS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, B.; Dendooven, T.; Sinha, D.; Roeselova, A.; Cameron, T.; De Lay, N.; Bandyra, K. A cooperative PNPase-Hfq-RNA carrier complex facilitates bacterial riboregulation. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2901–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay ND, Gottesman S. 2011. Role of polynucleotide phosphorylase in sRNA function in Escherichia coli. RNA (New York, NY) 17:1172–1189.

- Menendez-Gil, P.; Catalan-Moreno, A.; Caballero, C.J.; Toledo-Arana, A. Staphylococcus aureus ftnA 3’-Untranslated Region Modulates Ferritin Production Facilitating Growth Under Iron Starvation Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 838042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beinert H, Kennedy MC. 1993. Aconitase, a two-faced protein: enzyme and iron regulatory factor. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 7:1442–1449.

- Walden, WE. 2002. From bacteria to mitochondria: Aconitase yields surprises. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99:4138.

- Beinert, H.; Kennedy, M.C.; Stout, C.D. Aconitase as iron-sulfur protein, enzyme, and iron-regulatory protein. Chem. Rev. 2010, 96, 2335–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang DK, Jeong J, Drake SK, Wehr NB, Rouault TA, Levine RL. 2003. Iron regulatory protein 2 as iron sensor: Iron-dependent oxidative modification of cysteine. The Journal of biological chemistry 278:14857–14864.

- Beinert H, Holm RH, Münck E. 1997. Iron-sulfur clusters: Nature’s modular, multipurpose structures. Science (New York, NY) 277:653–659.

- Dupuy, J.; Volbeda, A.; Carpentier, P.; Darnault, C.; Moulis, J.-M.; Fontecilla-Camps, J.C. Crystal Structure of Human Iron Regulatory Protein 1 as Cytosolic Aconitase. Structure 2006, 14, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentze, M.W.; Kühn, L.C. Molecular control of vertebrate iron metabolism: mRNA-based regulatory circuits operated by iron, nitric oxide, and oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 8175–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, K.R.; Clarke, S.L.; Ho, Y.-H.; Bruss, M.D.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Anderson, S.A.; Eisenstein, R.S. Differential translational control of 5′ IRE-containing mRNA in response to dietary iron deficiency and acute iron overload. Metallomics 2020, 12, 2186–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Goforth, J.B.; Eisenstein, R.S. Iron-dependent post transcriptional control of mitochondrial aconitase expression. Metallomics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.L.; Di Jeso, B.; Rao, K.; Klausner, R.D.; Harford, J.B. Two genetic loci participate in the regulation by iron of the gene for the human transferrin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 1787–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.; Galy, B.; Schwanhaeusser, B.; Blake, J.; Bähr-Ivacevic, T.; Benes, V.; Selbach, M.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Hentze, M.W. Iron regulatory protein-1 and -2: transcriptome-wide definition of binding mRNAs and shaping of the cellular proteome by iron regulatory proteins. Blood 2011, 118, e168–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michta E, Schad K, Blin K, Ort-Winklbauer R, Röttig M, Kohlbacher O, Wohlleben W, Schinko E, Mast Y. 2012. The bifunctional role of aconitase in Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. Environmental Microbiology 14:3203–3219.

- Jordan PA, Tang Y, Bradbury AJ, Thomson AJ, Guest JR. 1999. Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of Escherichia coli aconitases (AcnA and AcnB). Biochemical Journal 344:739.

- Banerjee, S.; Nandyala, A.K.; Raviprasad, P.; Ahmed, N.; Hasnain, S.E. Iron-Dependent RNA-Binding Activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Aconitase. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 4046–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, D.J.; A Rouault, T.; Tang, C.K.; Chin, J.; Harford, J.B.; Klausner, R.D. Reciprocal control of RNA-binding and aconitase activity in the regulation of the iron-responsive element binding protein: role of the iron-sulfur cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7536–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Guest, J.R. Direct evidence for mRNA binding and post-transcriptional regulation by Escherichia coli aconitases. Microbiology 1999, 145, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold B, Rodriguez GM, Marras SA, Pentecost M, Smith I. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis IdeR is a dual functional regulator that controls transcription of genes involved in iron acquisition, iron storage and survival in macrophages. Mol Microbiol 42:851–865.

- Shell, S.S.; Wang, J.; Lapierre, P.; Mir, M.; Chase, M.R.; Pyle, M.M.; Gawande, R.; Ahmad, R.; Sarracino, D.A.; Ioerger, T.R.; et al. Leaderless Transcripts and Small Proteins Are Common Features of the Mycobacterial Translational Landscape. PLOS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazzolotto, X.; Gaillard, J.; Pantopoulos, K.; Hentze, M.W.; Moulis, J.-M. Human Cytoplasmic Aconitase (Iron Regulatory Protein 1) Is Converted into Its [3Fe-4S] Form by Hydrogen Peroxide in Vitro but Is Not Activated for Iron-responsive Element Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21625–21630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan PA, Tang Y, Bradbury AJ, Thomson AJ, Guest JR. 1999. Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of Escherichia coli aconitases (AcnA and AcnB).

- Kennedy, M.C.; Emptage, M.H.; Dreyer, J.L.; Beinert, H. The role of iron in the activation-inactivation of aconitase. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 11098–11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, A.H.; Stout, C.D. Structure of activated aconitase: formation of the [4Fe-4S] cluster in the crystal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 3639–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Quail, M.A.; Artymiuk, P.J.; Guest, J.R.; Green, J. Escherichia coli aconitases and oxidative stress: post-transcriptional regulation of sodA expression. Microbiology 2002, 148, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guest, J.R. Direct evidence for mRNA binding and post-transcriptional regulation by Escherichia coli aconitases. Microbiology 1999, 145, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.; Tang, Y.; Imlay, J.A. Contrasting Sensitivities of Escherichia coli Aconitases A and B to Oxidation and Iron Depletion. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, J.C.; Lukey, P.T.; Robb, L.C.; McAdam, R.A.; Duncan, K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong DK, Lee BY, Horwitz MA, Gibson BW. 1999. Identification of fur, aconitase, and other proteins expressed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis under conditions of low and high concentrations of iron by combined two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Infection and immunity 67:327–336.

- Serio, A.W.; Pechter, K.B.; Sonenshein, A.L. Bacillus subtilis Aconitase Is Required for Efficient Late-Sporulation Gene Expression. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 6396–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alén C, Sonenshein AL. 1999. Bacillus subtilis aconitase is an RNA-binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96:10412–10417.

- Wilson, T.J.G.; Bertrand, N.; Tang, J.; Feng, J.; Pan, M.; Barber, C.E.; Dow, J.M.; Daniels, M.J. The rpfA gene of Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris, which is involved in the regulation of pathogenicity factor production, encodes an aconitase. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.M.; Maier, R.J. Aconitase-Mediated Posttranscriptional Regulation of Helicobacter pylori Peptidoglycan Deacetylase. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 5316–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglesby-Sherrouse, A.G.; Murphy, E.R. Iron-responsive bacterial small RNAs: variations on a theme. Metallomics 2013, 5, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, E.; Gottesman, S. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4620–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, E.; Escorcia, F.E.; Gottesman, S. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, E.; Gottesman, S. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4620–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvail, H.; Massé, E. Regulating iron storage and metabolism with RNA: an overview of posttranscriptional controls of intracellular iron homeostasis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2011, 3, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadner, R.J. Regulation by Iron: RNA Rules the Rust. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6870–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilderman, P.J.; Sowa, N.A.; FitzGerald, D.J.; FitzGerald, P.C.; Gottesman, S.; Ochsner, U.A.; Vasil, M.L. Identification of tandem duplicate regulatory small RNAs in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involved in iron homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9792–9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrault, M.; Leclair, E.; Kumeko, E.K.; Jacquet, E.; Bouloc, P.; Wang, H. Staphylococcal sRNA IsrR downregulates methylthiotransferase MiaB under iron-deficient conditions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0388823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Manhas, I.; Chaturvedi, D. Unveiling the orchestration: mycobacterial small RNAs as key mediators in host-pathogen interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1399280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, A.; Mooney, R.A.; Iaconi, A.; Landick, R.; Adhya, S. Mycobacterial RNA Polymerase Requires a U-Tract at Intrinsic Terminators and Is Aided by NusG at Suboptimal Terminators. mBio 2014, 5, e00931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, P.; Yellaboina, S.; Ranjan, A.; Hasnain, S.E. Computational prediction and experimental verification of novel IdeR binding sites in the upstream sequences of Mycobacterium tuberculosis open reading frames. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrick, E.R.; Barbier, T.; Chase, M.R.; Xu, R.; François, J.; Lin, V.H.; Szucs, M.J.; Rock, J.M.; Ahmad, R.; Tjaden, B.; et al. Small RNA profiling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies MrsI as necessary for an anticipatory iron sparing response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6464–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, K.; Ramesh, A.; Zhou, Z.; Weinberg, Z.; Vallery, T.; Winkler, W.C.; Breaker, R.R. Bacterial Riboswitches Cooperatively Bind Ni 2+ or Co 2+ Ions and Control Expression of Heavy Metal Transporters. Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cotruvo, J.A. The czcD (NiCo) Riboswitch Responds to Iron(II). Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cotruvo, J.A. Reconsidering the czcD (NiCo) Riboswitch as an Iron Riboswitch. ACS Bio Med Chem Au 2022, 2, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Chaudhury, S.; Mehta, D.; Ramesh, A. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Discovery of iron-sensing bacterial riboswitches. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 17, 924–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, F.J.; Henkin, T.M. The S box regulon: a new global transcription termination control system for methionine and cysteine biosynthesis genes in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 30, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epshtein, V.; Mironov, A.S.; Nudler, E. The riboswitch-mediated control of sulfur metabolism in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5052–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, W.C.; Nahvi, A.; Sudarsan, N.; E Barrick, J.; Breaker, R.R. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding S-adenosylmethionine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2003, 10, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbabian, K.; Jamalli, A.; Zig, L.; Putzer, H. RNase Y, a novel endoribonuclease, initiates riboswitch turnover in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3523–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Raza, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.-L.; Bollinger, J.M.; Krebs, C.; Rouault, T.A. An iron–sulfur cluster in the zinc-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 helicase modulates its RNA-binding and -unwinding activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).