1. Introduction

Translation is a crucial biological process of protein synthesis within organisms, tightly regulated to ensure efficiency and accuracy [

1]. During translation, if a truncated mRNA is encountered, the ribosome stalls on it, depleting the available ribosome pool. Furthermore, truncated mRNA may encode abnormally toxic proteins, posing a significant threat to the organism’s survival [

2]. The mRNA surveillance pathway is essential for accurate gene expression and maintaining translational homeostasis, with trans-translation serving as the primary quality control system for protein synthesis that has evolved in bacteria [

3]. Transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA), which is the core component of trans-translation system, consists of a tRNA-like domain that carries alanine and an mRNA-like domain that encodes the SsrA degradation tag and stop codon. tmRNA is delivered to the ribosome’s A site by its partner proteins SmpB and EF-Tu-GTP, enabling the stalled ribosome to switch templates and resume translation of the coding sequence within the tmRNA molecule [

4].

Trans-translation is conserved across bacteria and is essential in many species [

5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the SmpB-SsrA system plays a significant biological role. For instance, the

smpB mutant of

Salmonella typhimurium exhibits defects in survival within macrophages, while the

ssrA mutant shows reduced virulence [

6,

7]. In

Escherichia coli, both

ssrA and

smpB mutants display increased sensitivity to various antibiotics, as well as to stresses such as acid, weak acid salicylic acid, high temperature, and peroxides, with

smpB mutants being more susceptible than

ssrA mutants [

8]. Although numerous studies indicate that the phenotypes resulting from the deletions of the

smpB gene and the

ssrA gene are similar [

9,

10], the mechanisms underlying the increased vulnerability of

smpB mutants under most stress conditions remain unclear.

Gene expression is influenced not only by transcription rates but also significantly by post-transcriptional regulation, where translation rates and mRNA decay play crucial roles in determining the final protein levels [

11]. This suggests that the SmpB-SsrA system may be involved in the regulation of gene expression. Research has shown that

ssrA plays an important role in the transcriptional regulation of

Bacillus subtilis spores, as the absence of

ssrA prevents the synthesis of active σ

k [

12]. Additionally,

ssrA can regulate the levels of active Lac repressor and control the cell cycle in

Caulobacter crescentus by mediating the removal of the regulatory factor CtrA [

13,

14]. In

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis,

smpB-ssrA mutants exhibit severe defects in the expression and secretion of virulence effector proteins, with these defects occurring at the transcriptional level [

15]. Furthermore, tmRNA has been shown to act as an antisense RNA targeting crtMN mRNA, inhibiting the synthesis of pigments in

Staphylococcus aureus [

16]. Studies have also found that SmpB directly or indirectly regulates the expression of at least 4% of the proteome of

S. Typhimurium [

17]. These findings indicate that SmpB and tmRNA may play important roles in gene regulation.

Previously, it was believed that tmRNA and SmpB could not function in the absence of each other [

18]. However, in

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, bacteria can survive normally when

smpB is knocked out without altering

ssrA [

19]. Additionally, six bacterial species were found to lack only tmRNA, while sixteen species lacked only

smpB, suggesting that there are more independent functions between tmRNA and SmpB than previously recognized [

20]. While most studies focus on revealing the cooperative functions of the two, there has been relatively little attention paid to the pathways and activities in which they participate independently.

Aeromonas veronii is found in various aquatic environments and serves as a pathogen for aquatic animals, capable of causing diseases such as skin ulcers and systemic hemorrhagic septicemia in fish [

21,

22]. Additionally, it is an emerging human intestinal pathogen frequently identified in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [

23]. More than 300 virulence factors have been characterized in

A. veronii, with aerolysin, microbial collagenase, and various hemolysins detected in all strains isolated from patients suffering from gastrointestinal diseases [

24]. Our previous research demonstrated that the knockout of

ssrA and

smpB reduces the virulence of

A. veronii [

25], while

smpB influences its antibiotic resistance [

26]. Furthermore, the knockout of

tmRNA affects its metabolism and resistance to antibiotics that target the cell wall [

27].

In this study, we characterized the expression dynamics of ssrA and smpB in A. veronii. We also investigated the changes in the responses of ssrA and smpB single knockout strains to environmental stress and their ability to utilize various carbon sources. Through transcriptomic analysis, we identified differentially expressed genes to explore the similarities and differences in the regulatory effects of SsrA and SmpB on gene expression. Our findings indicate that SsrA and SmpB collaboratively regulate the utilization of L-asparagine and D-mannitol, as well as the synthesis of iron transporters. However, they exhibit independent or opposing effects in response to starvation, low iron, high sodium stress, peptidoglycan synthesis, and bacterial chemotaxis. Furthermore, we discovered that the cooperation between SsrA and SmpB is enhanced under nutrient-deficient conditions, while SsrA and SmpB demonstrate greater independence in nutrient-rich environments. This study provides significant evidence and critical insights into the novel functions of tmRNA and SmpB in A. veronii, which are independent of trans-translation.

3. Discussion

mRNA synthesis can be interrupted by various events, including premature transcription termination, nuclease activity, and physical damage. When the ribosome reaches the 3’ end of a truncated mRNA, it becomes trapped in an incomplete translation complex [

31]. The tmRNA-SmpB system specifically recognizes these stalled translation complexes and releases the blocked ribosomes, which is crucial for maintaining the cell’s protein synthesis capacity. Under adverse growth conditions, the RNase toxin components of toxin-antitoxin systems, such as RelE and MazF, can cleave most intracellular mRNA, resulting in the production of a large amount of truncated mRNA, which allows cells to conserve resources during periods of severe stress [

32]. Under optimal growth conditions, these toxins are activated only in a small fraction of cells [

33].

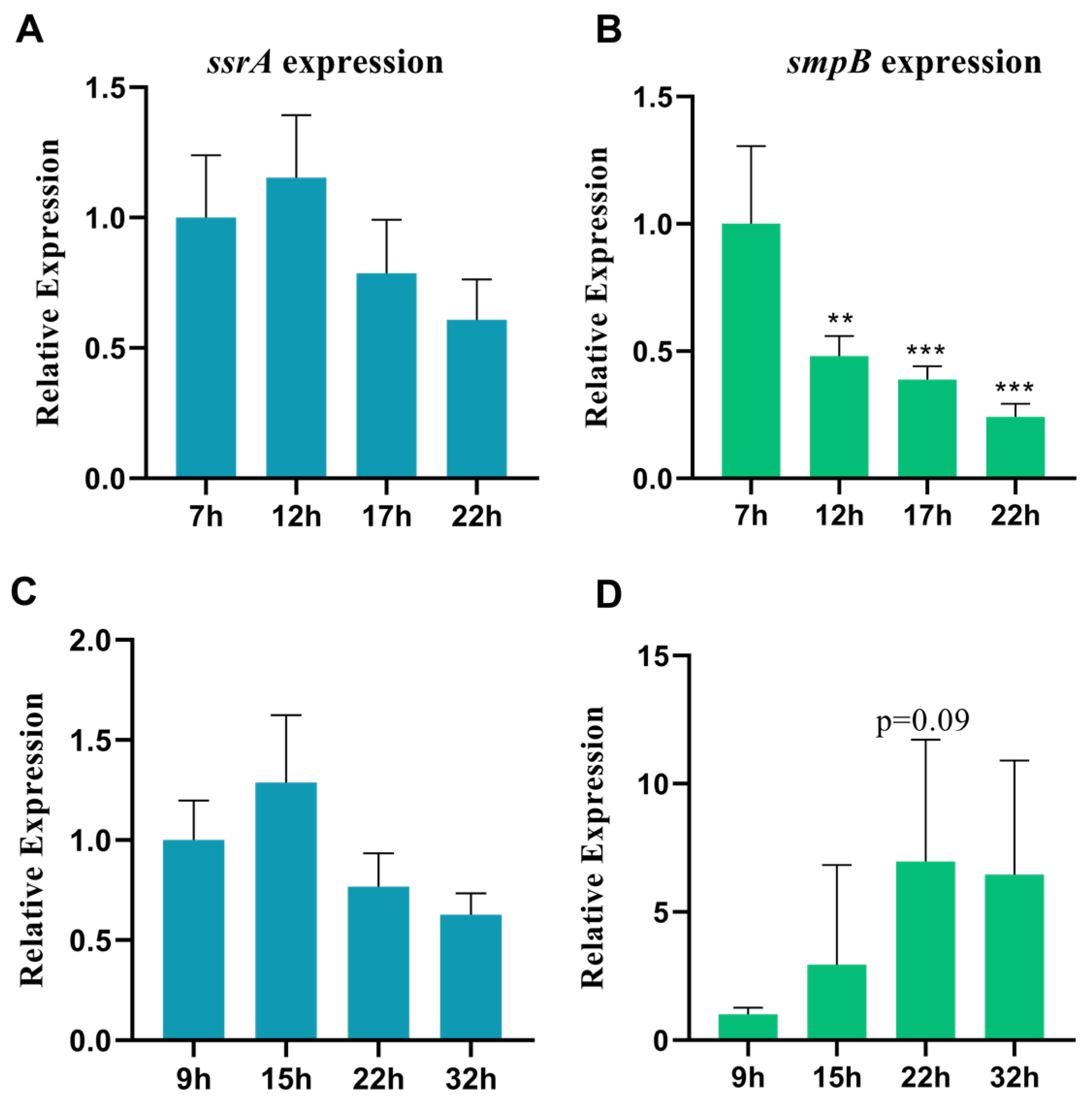

E. coli mutants lacking trans-translation activity show defects in recovering from toxin-induced stasis, indicating that trans-translation is important for resuming growth after prolonged severe nutritional stress [

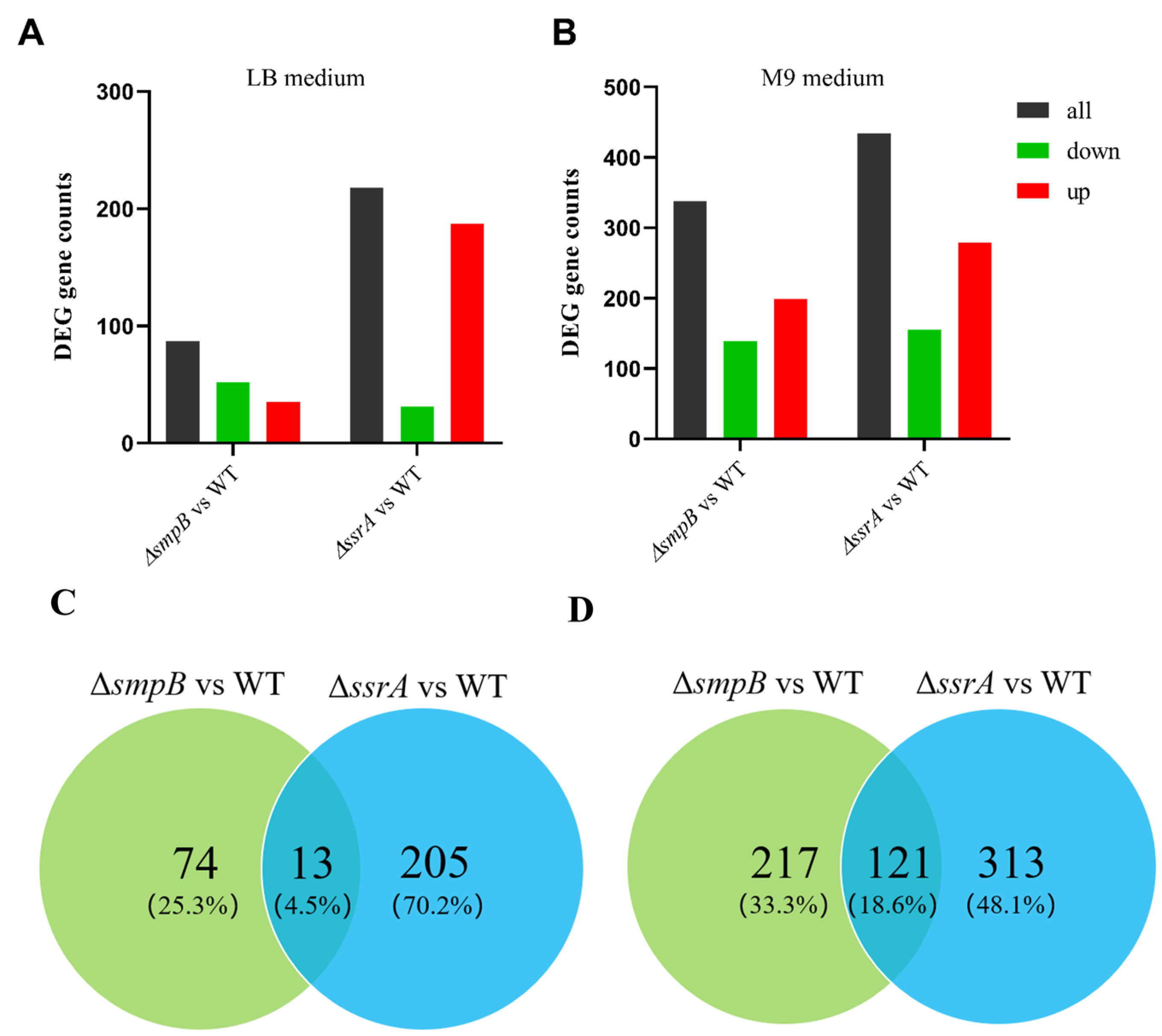

34]. The findings of this study further elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which the trans-translation system responds to severe nutritional stress. First, our detection of the expression levels of

ssrA and

smpB genes indicates that the trans-translation system is activated under nutrient-deficient conditions through the responsive expression of

smpB. This also helps explain why strains with a single knockout of

smpB are more vulnerable under the same nutritional stress conditions compared to strains with a single knockout of

ssrA. Second, our transcriptomic analysis reveals that the total number of differentially expressed genes and co-regulated genes in the Δ

ssrA and Δ

smpB strains under M9 conditions is higher than these under LB conditions. The increase in co-regulated genes under nutrient-poor conditions can be considered evidence of the enhanced cooperation between tmRNA and SmpB, highlighting the importance of the trans-translation system in nutrient deficiency. In addition, we also found that tmRNA is stably expressed throughout the growth cycle of

A. veronii, which is consistent with reports of stable tmRNA expression in

Staphylococcus aureus, where tmRNA has been used as a reference gene [

35].

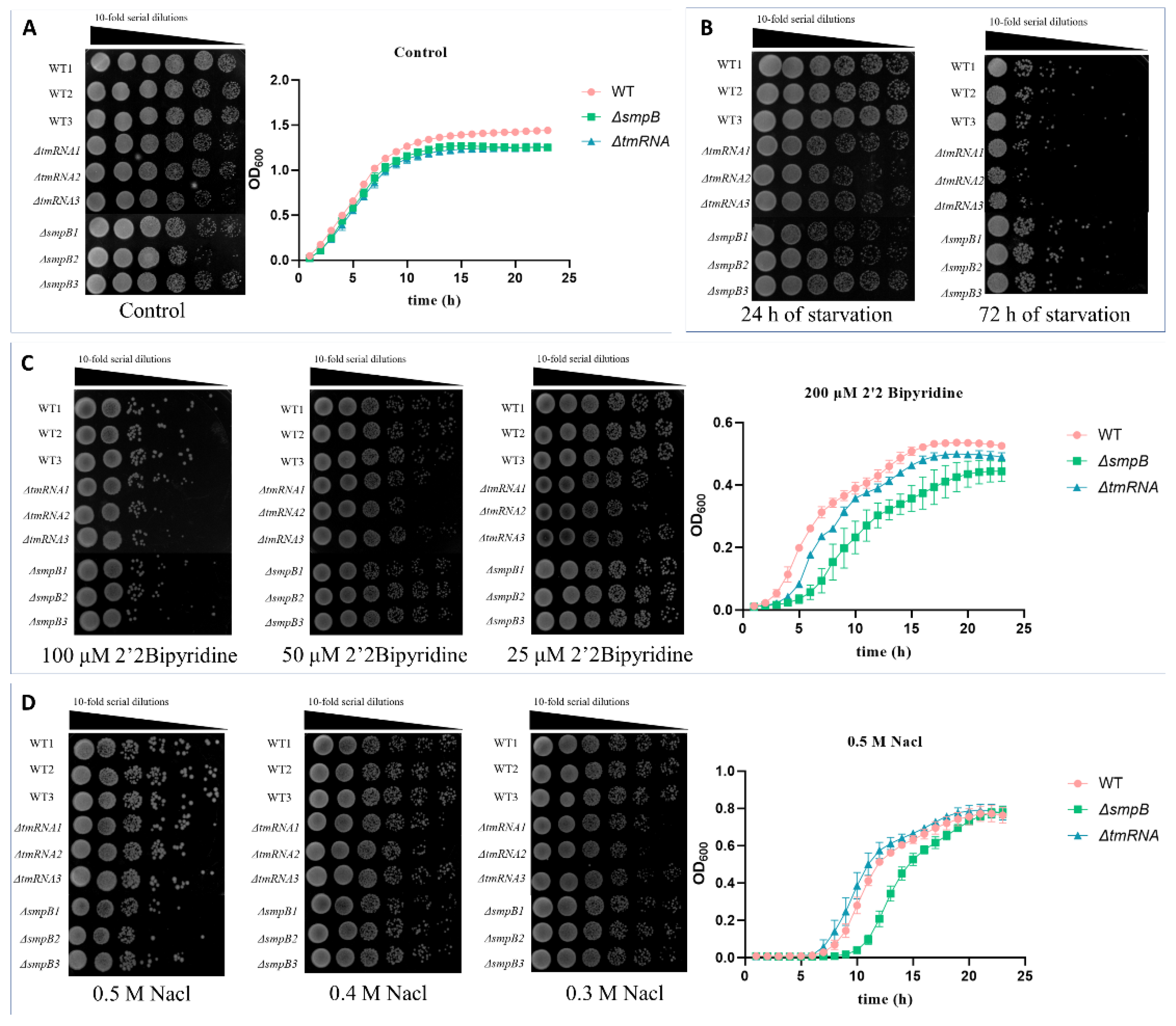

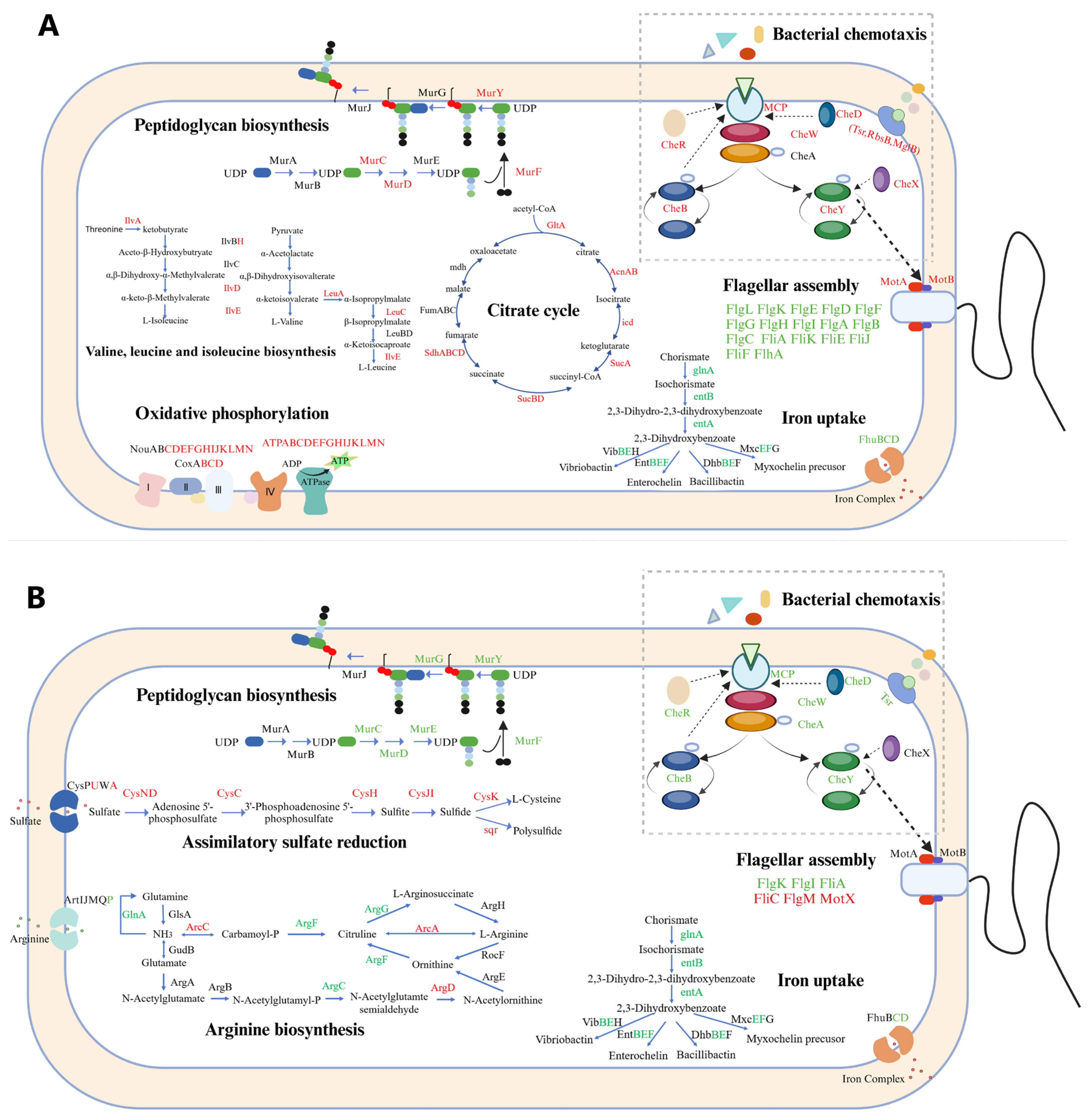

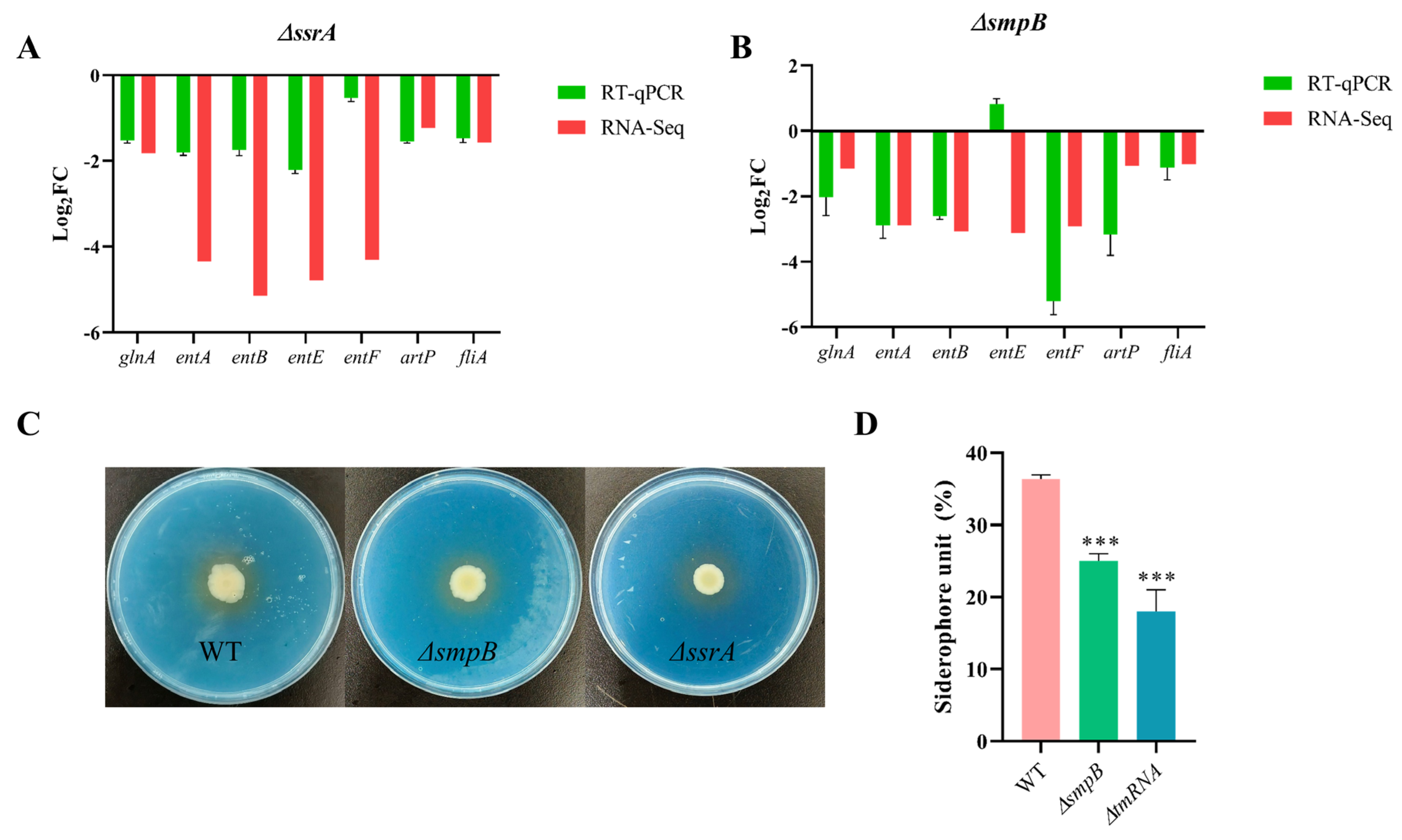

The results of this study indicate that tmRNA and SmpB collaborate and specialize in the response of pathogenic bacteria to stress and in carbon source utilization, with transcriptomic analysis providing a series of molecular insights into these phenotypic observations. Here, we further validated the impact of tmRNA and SmpB on the iron uptake capability of

A. veronii. Both RT-qPCR and phenotypic experiments demonstrated the positive role of tmRNA and SmpB in the synthesis of siderophore. Additionally, when pathogenic bacteria are exposed to osmotic pressure from the environment, peptidoglycan plays a crucial role in protecting the bacteria from external and cytoplasmic stress while maintaining their cellular morphology [

36]. Bacteria sense physical stimuli related to changes in external osmotic pressure and promptly regulate genes to sustain cellular viability [

37]. Transmembrane signal transduction primarily relies on two-component systems (TCS) and membrane-bound chemical receptors, such as components of chemotaxis systems [

38]. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the deletion of

smpB led to a significant downregulation of genes associated with the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway and chemotaxis systems, while the deletion of

ssrA had the opposite effect on the same set of genes. This initially explains the significant growth inhibition observed in the Δ

smpB strain under 0.5 M NaCl stress conditions, while the growth of the Δ

ssrA strain was even slightly higher than that of the wild type (

Figure 2D). Furthermore, we found that the deletion of

ssrA led to a significant reduction in the expression of arginine transporter-related genes

artM,

artQ, and

artP, while the deletion of

smpB resulted in a notable decrease in the expression of

artP. Although bacteria can synthesize L-arginine on their own, it is energetically more advantageous to uptake L-arginine from the environment at the expense of ATP [

39]. The changes in arginine transporter-related genes in the Δ

ssrA and Δ

smpB strains explain the slower growth of these strains compared to the wild type when L-arginine is the sole carbon source (

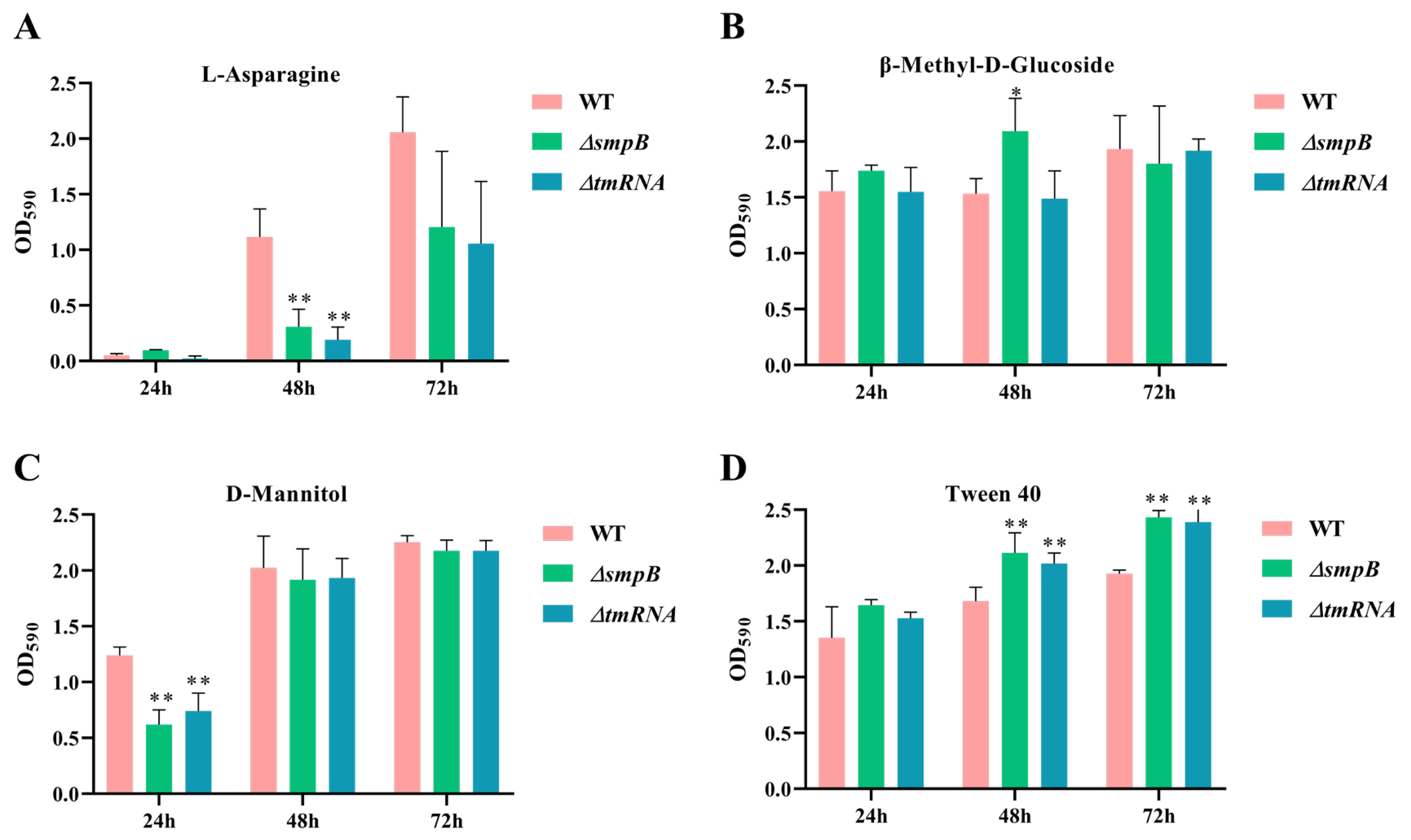

Figure 4C).

The trans-translation system is commonly understood to regulate gene expression by using the peptide tag encoded by tmRNA to facilitate the rapid degradation of rescue proteins. For example, in

C. crescentus, tmRNA targets multiple proteins involved in DNA replication, recombination, and repair, with tmRNA deletion causing delays in DNA replication initiation [

40]. In our previous study, GlnA was identified as a substrate of tmRNA [

41], and here we found that

glnA is significantly downregulated in the Δ

ssrA and Δ

smpB strains. Additionally, we observed a significant downregulation of tonB, a gene encoding a transmembrane iron transporter, in both strains. Twelve TonB-dependent receptors in

C. crescentus have been identified as tmRNA substrates [

40]. This raises the question of how tmRNA’s tagging activity primarily affects protein levels while also influencing transcription levels. One possible explanation is that tmRNA tags certain transcription factors, such as σ

k[

12], thereby regulating downstream expression. Alternatively, tmRNA may directly bind to target mRNAs as sRNA. Future studies should explore tmRNA’s regulatory mechanisms on specific genes from these two perspectives.

The collaboration and functional roles of tmRNA and SmpB have been extensively studied, but research on their independent pathways and activities is limited [

20]. Our transcriptomic results indicate that the KEGG pathways involving tmRNA and SmpB are inconsistent, with only 13 co-regulated genes (4.4% of the total DEGs) under LB conditions, providing direct evidence for their independent functions. In this study, we found that tmRNA and SmpB regulate peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial chemotaxis gene expression with opposing activities. Previous research showed that tmRNA deletion increases GlcNAc content in the cell wall and upregulates peptidoglycan biosynthesis genes, enhancing resistance to osmotic stress [

27]. Conversely, the deletion of

smpB increases sensitivity to high sodium osmotic pressure. These phenotypic results align with transcriptomic changes, indicating a functional division between tmRNA and SmpB in cell wall synthesis and osmotic stress response. Flagellum synthesis is energy-intensive and fundamental to bacterial chemotaxis [

42]. We observed significant downregulation of flagellar genes in the Δ

ssrA strain, likely due to reduced protein synthesis and energy utilization, consistent with findings in

B. subtilis [

28] and

Y. pseudotuberculosis [

15]. However, the upregulation of multiple chemotaxis genes in the Δ

ssrA strain contradicts observations in

B. subtilis [

28] and is inconsistent with the downregulation of flagellar genes in

A. veronii. Given the unclear distribution, function, and regulatory relationships between chemotaxis gene clusters and flagellar synthesis genes in

A. veronii, tmRNA may serve as a key clue for elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of chemotactic activity in this organism.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Media

Aeromonas veronii C4 and its derivatives were cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or M9 medium with shaking at 30°C. 50 μg/mL ampicillin (Amp) was supplemented for regular cultivation of

A. veronii strains. CAS medium was used to measure siderophore production [

43]. Each 1 L of CAS medium contains 20% sucrose 10 mL, 10% acid hydrolyzed casein 30 mL, 1 mmol/L CaCl

2 1 mL, 1 mmol/L MgSO

4 20 mL, Agar 15 g, and phosphate buffer 50 mL. CAS detection staining solution were slowly added at 60℃.

4.2. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the specified cultures using the Bacterial Total RNA Isolation kit (Shengong, Shanghai, China), and genomic DNA remnants were eliminated with gDNA Wiper Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). After assessing the concentration and purity of the RNA, 1 μg of RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis with HiScript II QRT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The resulting cDNA was then diluted for RT-qPCR reactions conducted on an ABI Prism

® 7300 instrument (ABI, New York, NY, USA), with fluorescence detection performed using ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The

gapdH gene served as a reference for data normalization and all the primers were designed using Primer Premier 6 software (

Table S1). Relative expression levels were quantified using the 2

−ΔΔCT method [

44].

4.3. Phenotypic Determination Under Stress Conditions

For the measurement of growth curves, the overnight cultures were collected at an OD600 of 1, diluted 1:100 into LB medium, and cultivated on a 96-well microplate at 30℃. Optical densities of the cultures were recorded using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTeK) at 600 nm at 1-hr intervals until 24 h. For the starvation test, stationary phase cultures grown in LB were washed three times with phosphate buffer solution. The culture was diluted to the same OD600 in a phosphate buffer and incubated without shaking at 30°C for different time points. A ten-fold serial dilution of the bacterial suspension was prepared, and 3 μL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates. For low iron and high sodium salt stress, the culture was washed 3 times with PBS, then diluted to the same OD600 value. A ten-fold serial dilution of the bacterial suspension was prepared, and 3 μL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates supplemented with different concentrations of 2’2 bipyridine or sodium chloride. For the growth curves measured under other stress conditions mentioned in this paper, the wild type and its derived strains were transferred to LB medium supplemented with corresponding compounds with the same OD value. For the determination of growth curves at different pH conditions, LB medium is adjusted with hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide to the specified pH value, filtered, and then inoculated with bacteria.

4.4. Carbon Source Utilization Capacity Testing

BIOLOG ECO microplate method was used to analyze the carbon source metabolic function of A. veronii. Overnight cultures were diluted with sterile water to the same OD600 value. BIOLOG ECO microplate (Biolog, Hayward, CA, USA)was preheated to 25℃ before use, and 150 μL diluted liquid was added into each hole. The sterile water was added as the control. The absorption value of 590 nm was read by microplate reader at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h, 120 h and 144 h at 30℃. The experiment was repeated three times.

4.5. RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

The strains were incubated in LB or M9 medium with the same initial OD600 indicative of the stationary stage. The cells were collected and lysed and total RNA were extracted by phenol-chloroform. RNA degradation and contamination was monitored on 1% agarose gels. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The resulting sequence was mapped to the reference genome of Aeromonas veronii C4 (NCBI reference sequence: GCF_008693705.1). RSEM and DESeq2 software were used to calculate gene expression levels to compare and analyze gene expression differences among samples. The threshold values of significant differences were p < 0.05 and | log2FC | ≥1. The significantly differentially expressed genes were analyzed for GO and KEGG functional enrichment.

4.6. Siderophore Production Assay

For qualitative analysis, after the overnight culture was washed twice with PBS, the bacterial suspension was diluted to the same OD600 value, and 5 μL of liquid was cultured on the CAS agar plate at 30℃ for 5 days. The siderophore formation was preliminarily determined by the size and color of yellow chelating rings around bacterial colonies. For quantitative analysis, overnight cultures were transferred to new LB medium at the same OD600 value and incubated at 30°C for 36 h with shaking. 1 mL bacterial solution was centrifuged at 10000 r/min for 10 min, and 100 μL supernatant was added into the 96-well microplate and mixed with CAS detection solution in equal volume. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the absorbance value of the mixture (As) was measured at the wavelength of 630 nm. The absorbance of uninoculated medium mixed with CAS reagent was determined as the reference ratio (Ar). The percent siderophore unit (SU) was calculated according to the formula [(Ar-As)/Ar]× 100%.

Figure 1.

The genes ssrA and smpB exhibit different expression patterns in response to nutrition deletion. RT-qPCR was used to determine the relative expression levels of tmRNA (A, C) or smpB (B, D) at different times under LB conditions (A, B) or M9 conditions (C, D). Tukey’s post-test was used for statistical analysis, with **representing P < 0.01, ***representing P < 0.005 in one-way ANOVA.

Figure 1.

The genes ssrA and smpB exhibit different expression patterns in response to nutrition deletion. RT-qPCR was used to determine the relative expression levels of tmRNA (A, C) or smpB (B, D) at different times under LB conditions (A, B) or M9 conditions (C, D). Tukey’s post-test was used for statistical analysis, with **representing P < 0.01, ***representing P < 0.005 in one-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

tmRNA and SmpB cooperate or independently participate in the responses to starvation, osmotic pressure, and low iron stress. For the determination of the growth curve, the bacteria were transferred to LB medium supplemented with 200 μM 2,2’-bipyridine or 0.5 M sodium chloride. Data were presented as mean± SD from three replicates. For the plate experiment, after the overnight culture was washed with PBS, a ten-fold serial dilution of the bacterial suspension was prepared, and 3 μL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates supplemented with different concentrations of 2’2 bipyridine or sodium chloride. For the starvation treatments, bacterial suspensions were allowed to stand in PBS buffer and dot on LB plates after 24 h or 72 h.

Figure 2.

tmRNA and SmpB cooperate or independently participate in the responses to starvation, osmotic pressure, and low iron stress. For the determination of the growth curve, the bacteria were transferred to LB medium supplemented with 200 μM 2,2’-bipyridine or 0.5 M sodium chloride. Data were presented as mean± SD from three replicates. For the plate experiment, after the overnight culture was washed with PBS, a ten-fold serial dilution of the bacterial suspension was prepared, and 3 μL of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates supplemented with different concentrations of 2’2 bipyridine or sodium chloride. For the starvation treatments, bacterial suspensions were allowed to stand in PBS buffer and dot on LB plates after 24 h or 72 h.

Figure 3.

tmRNA and SmpB participate in the metabolism of different types of carbon sources cooperatively or independently. WT, ΔtmRNA and ΔsmpB were inoculated on BIOLOG ECO microplate at 30℃ with L-aspartate (A), β-Methyl D-glucoside (B), D-mannitol (C) and Tween 40 (D) as sole carbon sources. The absorption values were recorded at 590 nm at an interval of 24 hours. Data were presented as mean± SD from three replicates. Tukey’s post-test was used for statistical analysis, with * representing P < 0.05, ** representing P < 0.01 in one-way ANOVA.

Figure 3.

tmRNA and SmpB participate in the metabolism of different types of carbon sources cooperatively or independently. WT, ΔtmRNA and ΔsmpB were inoculated on BIOLOG ECO microplate at 30℃ with L-aspartate (A), β-Methyl D-glucoside (B), D-mannitol (C) and Tween 40 (D) as sole carbon sources. The absorption values were recorded at 590 nm at an interval of 24 hours. Data were presented as mean± SD from three replicates. Tukey’s post-test was used for statistical analysis, with * representing P < 0.05, ** representing P < 0.01 in one-way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

The tmRNA and SmpB exhibit enhanced collaboration under nutrient deficiency condition, but show significant independence in nutrient enrichment condition. Total number of differential genes of ΔsmpB or ΔssrA compared with wild type were analyzed through histogram (A, B) or venn analysis (C, D) under LB medium (A, C) or M9 medium (B, D) conditions.

Figure 4.

The tmRNA and SmpB exhibit enhanced collaboration under nutrient deficiency condition, but show significant independence in nutrient enrichment condition. Total number of differential genes of ΔsmpB or ΔssrA compared with wild type were analyzed through histogram (A, B) or venn analysis (C, D) under LB medium (A, C) or M9 medium (B, D) conditions.

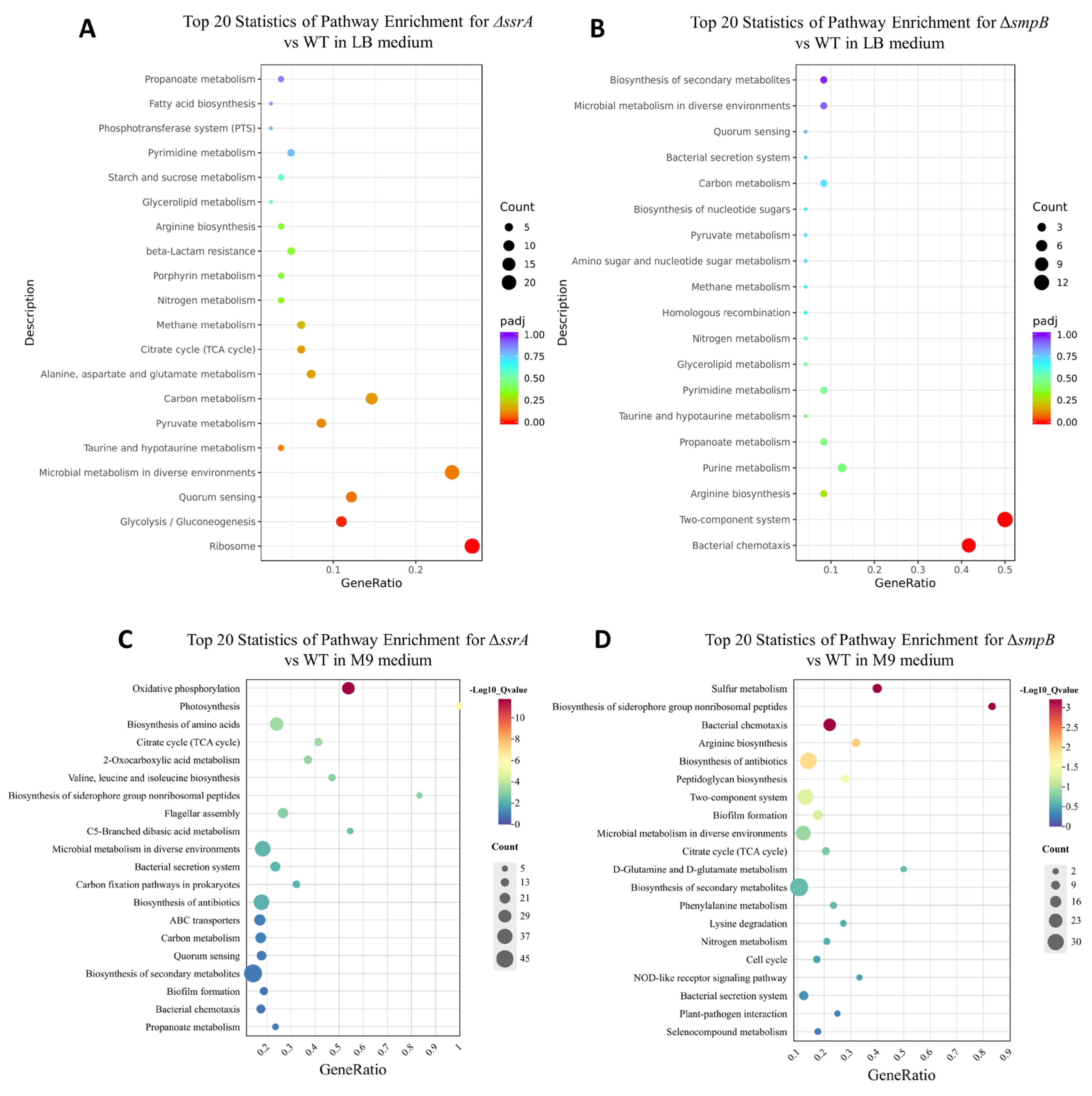

Figure 5.

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs based on the KEGG database. Top 20 statistics of pathway enrichment for ΔssrA vs WT (A, C) and ΔsmpB vs WT (B, D) in LB medium (A, B) and M9 medium (C, D).

Figure 5.

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs based on the KEGG database. Top 20 statistics of pathway enrichment for ΔssrA vs WT (A, C) and ΔsmpB vs WT (B, D) in LB medium (A, B) and M9 medium (C, D).

Figure 6.

The model for the changes of cellular processes in ΔssrA (A) and ΔsmpB (B) as compared with the wild type based on the highly enriched pathways under M9 culture conditions. Red, green, and black marked genes indicate theses with significant upregulation (FC > 2 and p-value < 0.05), significant downregulation (FC < 0.5 and p-value < 0.05), and no significant regulation (0.5 ≤ FC ≤ 2 or p-value ≥ 0.05), respectively.

Figure 6.

The model for the changes of cellular processes in ΔssrA (A) and ΔsmpB (B) as compared with the wild type based on the highly enriched pathways under M9 culture conditions. Red, green, and black marked genes indicate theses with significant upregulation (FC > 2 and p-value < 0.05), significant downregulation (FC < 0.5 and p-value < 0.05), and no significant regulation (0.5 ≤ FC ≤ 2 or p-value ≥ 0.05), respectively.

Figure 7.

tmRNA and SmpB cooperatively regulate siderophore synthesis. RT-qPCR validation of genes involved in siderophore synthesis in ΔssrA (A) and ΔsmpB (B). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of siderophore formation. For qualitative analysis (C), 5μLbacterial suspension were cultured on CAS agar plates at 30 ℃ for 5 days. The yellow halo shows that siderophores produced by bacteria can strip the blue complex formed by cas and Fe3+ from the medium, and the wild type produces a darker yellow halo. For quantitative analysis (D), the bacteria were cultured in LB medium for 36 h, centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 10 min, 100 μLsupernatant was mixed with equal volume cas detection solution, and the absorption value at 630 nm was measured after standing in the dark for 1 h. Error bars represented standard deviations of triplicate experiments. Tukey’s posttest was used to assess statistical significance with *** representing P < 0.005 in one-way ANOVA.

Figure 7.

tmRNA and SmpB cooperatively regulate siderophore synthesis. RT-qPCR validation of genes involved in siderophore synthesis in ΔssrA (A) and ΔsmpB (B). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of siderophore formation. For qualitative analysis (C), 5μLbacterial suspension were cultured on CAS agar plates at 30 ℃ for 5 days. The yellow halo shows that siderophores produced by bacteria can strip the blue complex formed by cas and Fe3+ from the medium, and the wild type produces a darker yellow halo. For quantitative analysis (D), the bacteria were cultured in LB medium for 36 h, centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 10 min, 100 μLsupernatant was mixed with equal volume cas detection solution, and the absorption value at 630 nm was measured after standing in the dark for 1 h. Error bars represented standard deviations of triplicate experiments. Tukey’s posttest was used to assess statistical significance with *** representing P < 0.005 in one-way ANOVA.