1. Introduction and Motivation

Neural Tax Networks

Neural Tax Networks (

2025);

Orphys, et al. (

2022) is building a proof-of-technology for a multi-modal AI system. The first modality is based on automated theorem-proving for enhanced first-order logic systems. This is realized by using the logic programming language ErgoAI

ErgoAI (

2024) for proving statements in tax law. So, in practice, it is a form of clausal resolution theorem proving. The second modality may use LLMs (Large Language Models) in two ways. The initial application of LLMs is to help users input information and understand output information. This application of LLMs is the focus of our comparison of modalities of LLMs and logical theorem-proving systems. The second application of LLMs will target the translation of tax law into ErgoAI. Both of these applications of LLMs are challenging and they have not been fully tried and tested yet.

Questions of language and the Löwenheim–Skolem theorems may impact the consistency of understanding were addressed in

Putnam (

1980).

This paper leverages logical model theory to better understand the limits of these two modalities. Particularly, this paper gives insight into limits on combining LLMs and theorem proving systems. We make a key assumption: the LLMs work with an uncountable number of words. We argue this is not an unreasonable assumption since deeper specialization requires new words and these words differ from previous words since they represent new concepts. Moreover, (1) LLMs are based on very large amounts of data and they are occasionally updated with new words, and (2) natural language adds new words over time while fewer words are lost.

We also argue resolution theorem proving systems may have domains that contain a countable number of facts in their domain.

A key question we work on is: Suppose an theorem-proving system does not add any new rules while new words, defining new concepts, are added to the system’s domain by an LLM. The theorem proving system’s rules work the same for the original domain while we add an uncountable domain by assumption for our LLMs.

So, a novel application of the Löwenheim–Skolem (L-S) Theorems, see Theorem 6, indicate the same rules of the theorem proving system can still work. Another view is from the Lefschetz Principle of first-order logic

Marker (

2002). This indicates the same first-order logic sentences can be true given specific models with different cardinalities. For instance, one model may have cardinality

and another may have cardinality

.

1.1. Technical Background

The domain of an LLM is the specific area of knowledge or expertise that the model is designed to understand. It’s essentially the context in which the LLM is trained and applied. Thus it determins the types of tasks it can perform and the kind of information it can process and generate.

Applying LLMs are in the next phase of our proof-of-technology. We already have basic theorem proving working in ErgoAI with several tax rules. It is the practical combination of these modalities that will allow complex questions to be precisely answered. Ideally, given the LLMs, the users will be able to easily work with the system.

Many theorem proving systems supply answers with explanations. In our case, these explanations are proofs from the logic-programming system ErgoAI. Of course, the Neural Tax Networks system assumes all facts entered by a user are true.

ErgoAI is an advanced multi-paradigm logic-programming system by Coherent Knowledge LLC

Coherent Knowledge (

2025);

ErgoAI (

2024). It is Prolog-based and includes non-monotonic logics, among other advanced features. For instance, ErgoAI supports defeasible reasoning. Defeasible reasoning allows a logical conclusion to be defeated by new information. This is sometimes how law is interpreted: If a new law is passed, then any older conclusions that the new law contradicts are dis-allowed.

The idea that proofs are syntactic and model theory is semantic goes back to, at least, the start of logical model theory. Of course, the semantics of model theory or LLMs may not align with the linguistic or philosophical semantics of language.

2. Multimodality and the Law

2.1. Expert Systems

Expert systems are AI systems that simulate the decision-making and reasoning of a human expert. These systems use a knowledge base with domain-specific information and rules. The knowledge base, domain specific information, and rules help these systems solve complex problems. Expert systems have been applied in many application domains.

A legal expert system is a domain-specific expert system that uses artificial intelligence for legal reasoning. These AI systems mimic human experts in the law. They provide support to the decision-making process. They can offer guidance on specific legal issues or tasks. These systems can help lawyers, legal professionals, or the public navigate legal processes, understand legal concepts, and complete legal forms. On one hand, there are discussions on limitations of expert systems in the the law

Leith (

2010);

Franklin (

2012);

Isozaki (

2024). On the other hand, there is work on programming languages for the law in addition to leagal reasoning systems. For instance, Catala is a programming language desinged for programming law. Its initial focus was US and French law

Merigoux, et al. (

2021).

2.2. Knowledge, Rule Bases and Inference Engines

For tax law expert systems, the knowledge base and rules are derived from statues enacted by legislatures, regulations issued by the U.S. Treasury Department and comparable state and local institutions, rulings issued by governmental organizations such as the Internal Revenue Service, and case law. Statutes are essentially the legal rules written in natural language. Case law contains the legal rulings and opinions governing how the language of statutes is to be interpreted and applied. Case law includes results of legal rulings and opinions. Case law is written in natural language. This knowledge and rules may be encoded in theorem proving systems.

An expert system’s inference engine applies the system’s rules contained in its knowledge base to the information (facts) provided by the user to produce conclusions. In the case of a tax law expert system the conclusions sought are the equivalent of rulings by a court of administrative body. Those conclusions are based on the facts of a particular situation provided to the system and are intended to be the same conclusions that would be reached by a court or a government regulator if a court of regulator were to consider the same set of facts. The objective in our case is to have percise facts that are provably accurate. An important requirement for the tax law system is full explainability: the answer to a query should contain the entire formal proof that leads to the conclusion. An ideal reasoning sequence is a proof tree.

2.3. LLMs and Other Approaches to Legal Reasoning

Large language models can be used to answer tax questions, but the responses they provide are frequently inaccurate. For instance, LLMs demonstrate behavior (in the form of answers) that can be confused with semantic understanding. LLMs often struggle with logical reasonings tasks. This is not surprising because LLMs are essentially artificial neural networks trained on huge corpora of data to generate answers to natural language queries. In many cases, neural networks work very well. But the rules neural networks generate are often very complex and not fathomable. So LLMs alone do not give any reasoning to justify their conclusions. Explainability for LLMs often requires other methods, or tools and is often multimodal.

Chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting

Xu, et al. (

2024) is a prompt engineering technique that aims to improve language models’ performance on tasks requiring logic, calculation and decision-making. It does this by structuring the input prompt to mimic human reasoning. To construct a CoT prompt, a system appends something like “Describe your reasoning in steps” or “Explain your answer step by step” to the end of their query to a large language model. In essence, this prompting technique asks the LLM both generate a result and also give details of the intermediate steps that led to that result.

CoT prompting can improve the performance of LLMs for simple logical reasoning tasks. These tasks may require a few reasoning steps. However, CoT often fails in complex logical reasoning tasks. They may not provide proof trees. These complex reasoning tasks need longer sequences of reasoning

Ye, et al. (

2024).

To address this problem, several neurosymbolic approaches

Ye, et al. (

2024);

Kirtania (

2024) use LLMs with theorem proving systems on complex logical reasoning tasks.

These multimodal approaches typically have the steps: (1) translation (e.g., using LLMs) from a natural language statement to a logical reasoning problem into a set of first-order logic formulas, (2) planning and execution the reasoning steps by a symbolic solver or a theorem-proving system to give answers to the logical reasoning problem, and (3) translation (e.g., using LLMs) of the solution from an enhanced logic expression to natural language.

Another direction to explore is improving the logical reasoning of an expert system to use explainable AI techniques for LLMs. Methods such as Shapley values or Integrated Gradients may compute attributions of features impacting results of AI. For an NLP application see

Goldshmidt (

2024). There are several papers

Explainable AI (

2025,

2);

Reviewing explainable AI (

2026) that study how explainable AI methods help explain conclusions of automated tax law systems. The Shapley values method is implemented in the

shap Python library

SHAP library (

2025). This library is integrated with gradient methods and implemented in Tensorflow and Captum.

Symbolic Chain-of-Thought (SymbCoT) also uses multimodality to handle the logical reasoning combined with LLMs

Xu, et al. (

2024). This LLM-based framework integrates symbolic expressions and logic rules with CoT prompting. That is, translating natural language into symbolic format and following structured plans to solve logical problems. However, CoT’s reliance on natural language is insufficient for precise logical calculations demanding symbolic expressions and strict rules. SymbCoT overcomes this by using LLMs to translate natural language queries into symbolic formats, create reasoning plans, and verify their accuracy. This multimodal combination of symbolic logic and natural language processing aims to make LLMs answers more logically explainable.

A trained expert system should be able to recognize the terminology of the specific knowledge area. First steps in this direction were made in an n-gram language model

Katz (

1995). Such models are now used for training LLMs. As system usage continues the clients questions and system answers are archived and can be used later in reverse reinforcement learning mode to fine tune the system. This is imitation learning, see, e.g.

Dixon, et al. (

2020).

2.4. Tax Preparation Systems

There are several commercial tax preparation software systems. These systems do not provide proofs of their conclusions. Rather they are highly structured in their data entry and focus on filling out tax forms.

Nay, et al.

Nay (

2024) discuss using LLMs to analyze taxes. There are some systems that offer multi-modal combinations of LLMs and logical proof systems. See for example

Pan, et al. (

2023).

This paper seeks insight on multimodal AI systems based on the foundations of computing and mathematics. There has also been work on the formalization of AI based on the foundations of computing, see for example

Bradford and Wollowski (

1995).

3. First-Order Logic Systems

First-order logic expressions have logical connectives and a unary symbol . They also have variables and quantifiers , functions and predicates. Functions and predicates represent relationships. The logical connectives, functions and predicates all can apply to the variables. The variables may be quantified. Formulas are well-formed and finite first-order logic expressions. Indeed, assume all expressions in first-order logic are finite and well-formed.

Proofs are syntactic structures. A proof of a first-order logic formula is a directed acyclic graph. If the proof’s goal is to establish an expression A is provable, then this directed acyclic graph terminates at this expression A. Some types of proofs are linear, others are trees and some are directed acyclic graphs. The vertices of a proof graph are facts, axioms, inference rules, and expressions. By substituting facts into variables, applying axioms, and applying inference rules formulas can sometimes be proved. If a logical formula is provable, then finding a proof often reduces to exhaustive search.

Consider a logical system, a logical formula H, and another logical formula C. The formulas H and C may be related as: If H is true, then C is true: . Another relationship between H and C is: H is assumed to be valid and it is used with inference rules, facts, axioms to prove C. In other words, H can contribute to C’s proof.

Listing 1 is a simplified ErgoAI rule for determining if an expenditure is a deduction. The notation ?X is that of a variable, the expression C :- H is a rule. This rule indicates that if H is true then conclude C is true.

|

Listing 1. A rule in ErgoAI |

?X:Deduction :-

?X:Expenditure,

?X[ordinary -> \true],

?X[necessary -> \true],

?X[forBusiness -> \true]. |

The ErgoAI rule mortal can have many facts or names declared as human . Hence an ErgoAI system can prove these individals listed as human to be mortal. Just as, any number of facts can be found that are expenditures that are ordinary, necessary and for business.

It is interesting that some modern principles of tax law are not all that different from ancient principles of tax law. The principles under-pinning tax law evolve slowly. Certain current tax principles appear to be very similar to some in the Roman Empire in the last 1,900+ years

Duncan-Jones (

1994);

Lidz (

2025). While the meaning of words evolves, ideally the semantics of tax law remains the same over time. Modern tax law is of course much more complex than ancient tax law, in large part because both commercial laws and bookkeeping have improved and become more complex (and more precise) than in ancient times which has allowed the creation of more complex financial transactions.

Under the legal theory of Originalism, the words in the tax law should be given the meaning those words had at the time the law was enacted. Scalia and Garner’s book is on how to interpret written laws (

Scalia and Garner,

1994, p 78). For example, they say,

“Words change meaning over time, and often in unpredictable ways.”

Assumption 1 (Originalism). A law should be interpreted based on the meaning of its words when the law was enacted.

Assumption A1 may be challenging for some LLMs. This is because many LLMs are trained on very recent natural langauge examples. Most of the world’s natural language text was posted or published in the last several years. This means LLMs, not restricted to old data, will focus on the meaning of words as they have been used in the last several years. Furthermore, new concepts and words regularly occur.

Of course, tax law can be changed quickly by a legislature. Assuming originalism, the meaning of the words in the newly changed laws, when the new laws are enacted, is the basis of understanding these new laws.

Context-free grammars generate specialized sets of strings. Many programming languages can have variables specified by regular expressions or context-free grammars.

Definition 1 (Context-free grammar (CFG)). A context-free grammar where V is a set of variables, Σ is a set of terminals or fixed symbols, P is a set of production rules so is such that where and , and is the start symbol.

For example, the terminals can be words from a natural language. A start symbol can be a sentence subject. A production rule can be where and N is a subject, B is a verb and O is an object. So the production rule describes simple English sentences.

The language generated by a context-free grammar is all strings of terminals that are generated by the production rules of a CFG. The number of strings in a language generated by some CFGs are countably infinite.

Definition 2 (Countable and uncountable numbers). If all elements of any set S of can be counted by some or all of the natural numbers , then S has cardinality . Equality holds when there is a correspondence between each element of the set S and a non-finite subset of .

Any set that has the same number of elements as the real numbers has cardinality and is uncountable.

There is a rich set of extensions and results beyond Definition 2, see for example

Cohen (

1994);

Hodel (

1994);

Shoenfield (

1994). The next theorem is classical. In our case, this result is useful for applications of the Löwenheim–Skolem (L-S) Theorems. See Theorem 6.

Theorem 1 (Domains from context free grammars). A context free grammar can generate a language of size .

Proof. Consider a context-free grammar made of a set of non-terminals V, a set of terminals , productions P and the start symbol S. Let , be the empty symbol.

Starting from

S, the set of all strings of terminals

w that can be derived from

P is written as,

So, the CFG G can generate all strings representing the natural numbers . All natural numbers form a countably infinite set, completing the proof. □

Our use of theorem proving systems is not limited to have context-free grammars describing facts in their domains. Many other grammars can recognize or produce similar countable infinite domains. However, context-free grammars are common and well-known.

On interesting thing is context-free grammars cannot be fully described by first-order logic.

3.1. Interpretations and Models

Consider a first-order logical system. Suppose E is formula of this system. A formula may have free variables. Alternatively, if all of a formula’s variables are quantified with either ∀ or ∃, then such a formula is a logic sentence. That is, a sentence is a formula with no free variables.

Definition 3 (Logical symbols of a first-order language

Hodel (

1994)).

The logical symbols of a first-order language are,

variables

logic connectives

quantifiers

scoping (, ) or [] or such-that :

equality =

The signature

of a logical system is the set of all

non-logical symbols and operators of a first-order language

Hodel (

1994).

Definition 4 (The signature

Hodel (

1994)).

Given a domain , the non-logical symbols of -language are,

Constants in D

n-ary functions, such a function has domain and range D.

n-ary relations, such a relation has domain and range .

Theorem 1 indicates with a context-free grammar, a theorem proving system can have an infinite signature from an infinite domain. See Theorem 1.

Definition 5 (-language). If , then this is an -language where L is the set of logical symbols and connectives, D is the domain, and σ is the signature of the system.

A formula is a well-formed expression made from an -language. A formula has no free-variables if each varible in is quantified by one of ∀ or ∃.

Definition 6 (Sentence). Consider a first-order formula from a -language. If has no free variables, then is a sentence.

Definition 7 (-theory or system). Consider a first-order -language and a set of axioms Γ, then together is a theory or system.

An interpretation defines a domain and semantics to functions and relations for formulas or sentences. An interpretation that makes a formula E true is a model. Given an interpretation, a formula may not be either true or false if the formula has free variables.

Definition 8 (First-order logic interpretation (

Hodel,

1994, p. 139)).

Consider a first-order logic language and a set I. The set I is an interpretation of iff the following holds:

There is a interpretation domain made from the elements in I

If there is a constant , then it maps uniquely to an element

If there is a function symbol where f takes n arguments, then there is a unique where is an n-ary function.

If there is a relation symbol where R takes n arguments, then there is a unique n-ary relation .

An interpretation I of a logic language includes all of the logical symbols in L.

Adding quantification, where E is a first-order formula, then this means if or if . Quantification is important to express laws as logic. Theorem proving languages such as Prolog or ErgoAI default to for any free variable x.

Consider the domain D, signature , and I is an interpretation. The interpretation I can be applied to a sentence. Given any interpretation, then any sentence must be or .

The statement indicates that E is provable in the logical system at hand. That is, E is a tautology. A tautology is a formula that is logically always true. For example, given a Boolean variable X then the formula must always be true so it is a tautology. The formula is a contradiction. Contradictions are always false. Similarly, indicates all interpretations of the system make E true. If an interpretation I in a logical system can express the positive integers and the sentence , then then is true. However, if I is updated to include , then .

Consider a formula E and a set of formulas F in the same logical system. If from the formulas in F, axioms and rules of the system, we can prove E, we write . In other words, from F can we prove E given the rules and axioms of the sytem. Similarly means we can substitute values from I into E giving . The formula is true when .

Definition 9 (First-order logic definitions). Given any set of first-order logic formulas E and an interpretation I, then E is:

Valid if every interpretation I is so that E is true

Inconsistent or Unsatisfiable if E is false under all interpretations I

Consistent or Satisfiable if E is true under at least one interpretation I

Theorem 2 (First-order logic is semi-decidable). Consider a set of first-order logic formulas E.

If E is true, then there is an algorithm that can verify E’s truth in a finite number of steps.

If E is false, then in the worst case there is no algorithm can verify E’s falsity in a finite number of steps.

Suppose H and C are first-order logic formulas. If H is provable, then it is valid so it satisfies all models.

Theorem 3 (Logical soundness). For any set of first-order logic formulas H and a first-order formula C: If , then .

Gödel’s completeness theorem

Hodel (

1994) indicates if a first-order logic formulas is valid, then it is provable. If

C satisfies all models

H, then

C is provable.

Theorem 4 (Logical completeness). For any set of first-order logic formulas H and a first-order logic formula C: If , then .

Listing 1 can be expressed in terms of a provability. See Listing 2.

Listing 2. Provability in ErgoAI

?X:Expenditure

^ ?X[ordinary -> \true ]

^ ?X[necessary -> \true ]

^ ?X[forBusiness -> \true ]

$\vdash$ ?X:Deduction

So, if there is an ?X that is an expenditure, and it is ordinary, necessary, and for busiess, then this is accepted as a proof that it is a deduction. That is, if the first four lines of the rule in Listing 2 are satisfied, then we have a proof that ?X is a Deduction. We have left out several conditions such as food is not always fully deductable and so on.

There are many rules that can be found in tax statutes. Many of them are complex, as well. Currently there are about instances of words in the US Federal tax statutes and about words in the US Federal case tax law. Of course most of these words are repeated many times.

4. Models and LLMs

Logic programming can illustrate logical semantics using the ⊧ symbol. Consider revisiting the rule

mortal and add the facts,

Then we can say

. That is, the interpretation

makes

and

true. Hence

is a model. For a general approach to logical models in logic programming, see for example

Bonner and Kifer (

1994).

In the case of LLMs, word are represented by vectors (embeddings) in high-dimensional space. Each feature of a word has a dimension. Each vector represents a different word. In many cases there are thousands of dimensions

Fast text (

2025). Similar vectors are have close semantic meanings. This is a central foundation for LLMs

Tunstall, et al. (

2022);

Wolfram (

2023).

The notion of semantics in LLMs is based on the similarity between word or word fragment vectors

Wolfram (

2023). These similarity measures form an empirical distribution. Over time, these empirical distributions change as the meanings of words evolve.

In the case of LLMs, we use to indicate semantics by adding that close word or phrase vectors can be substituted for each other.

Given two word vectors

x and

y both from the set of all word vectors

V and a similarity measure

. So values close to 1 indicate high similarity and values close to

indicate vectors whose words have close to the opposite meanings. The function

s can be a cosine similarity measure. In any case, suppose there are words

where for all

,

Then y is similar enough to x so y can be substituted for x given the threshold . We assume similarity measures stringent enough so all are finite. Substitutions can be randomly selected from , which may make this AI method seem human-like.

Consider a simplified case for deducting a lunch expense. That is, say is a model of ordinary. These terms may also be a model for necessary and for business for a business lunch. So [ordinary(Salad) -> \true] holds. But, a Zillion-Dollar-Frittata, costs about 200 times the cost of a salad or burger. So the Zillion-Dollar-Frittata is not a model of ordinary, though it is an interpretation of ordinary. So [ordinary(Zillion-Dollar-Frittata) -> \false]. However, all three of these Salad, Burger and Zillion-Dollar-Frittata may have some close dimensions, but their cost dimension(s) are not in alignment.

Definition 10 (Extended logical semantics for LLMs). Consider a model of a first-order formula . Then iff all pairs when the similarity is above a suitable threshold.

In Definition 10, since to start, then given the expression is true.

Definition 11 (Knowledge Authoring). Consider a set of legal statutes and case-law in natural language L, then finding equivalent first-order rules and facts and putting them all in a set R is expressed as, .

Knowledge authoring is very challenging

Gao, et al. (

2018). We do not have a solution for knowledge authoring even using LLMs. Consider the first sentence of US Federal Law defining a business expense

Cornell (

2025),

“26 §162 In general - There shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business, including—”

The full definition, not including references to other sections, is about 6,300 words. The semantics of each of the words must be defined in terms of facts and rules. Currently, our proof-of-technology has a basic highly structured UI for a user to enter facts. The proof-of-technology also builds simple queries with the facts. This is done using a standard UX interface. Our proof-of-technology system has a client-server cloud-based architecture where the proofs are done in ErgoAI on our backend. The semantics of a tax situation are entered by a user through the front end. These semantics consist of facts. We also add queries, as functions or relations, based on the user input.

Our goal is to have users enter their questions in structured subset of natural language

with the help of an LLM-based software bot. The user input is the set of natural language expressions

U. An LLM will

help translate these natural language statements

U into ErgoAI facts and queries that are compatible with the logic rules

R in ErgoAI. Accurate translations are challenging. We do not have an automated way to translate from user entered natural language tax questions into ErgoAI facts and queries. However, Coherent Knowledge LLC has recently announded a product, ErgoText, that may help with this step

ErgoText (

2025).

Definition 12 (Determining facts for R). Consider a natural language tax query U and its translation into both facts and a query into the expression G that is compatible with the ErgoAI rules R, then .

Using LLMs, Definition 12 depends on natural language word similarity. The words and phrases in user queries must be mapped to a query and facts in our ErgoAI rules R so ErgoAI can work to derive a result.

Definition 11 and Definition 12 can be combined to give the next definition.

Definition 13. Consider the ErgoAI rules and facts R representing the tax law and the ErgoAI user tax question as a query and facts . The query and facts are written as a formula G where since they must be compatible with the rules R. The proper formulas G must be built from as formula of R’s theory. Now theorem prover such as ErgoAI can determine whether, .

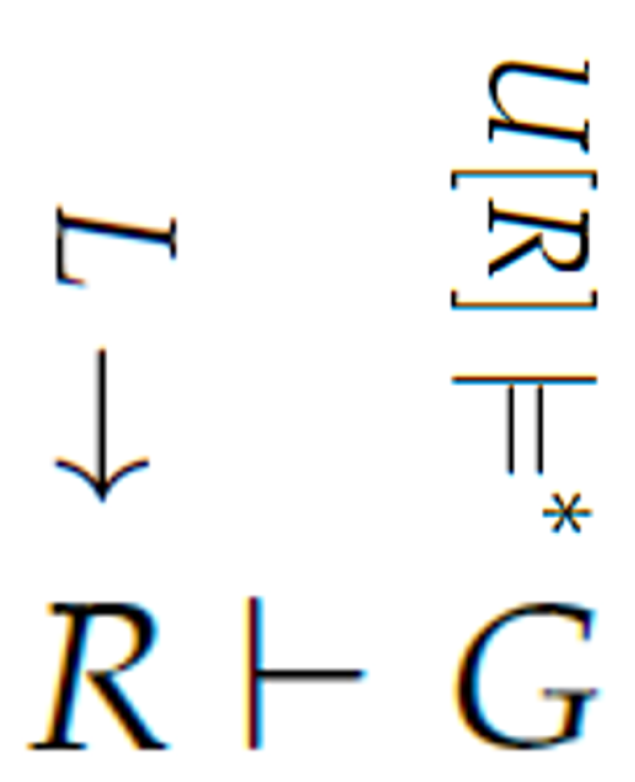

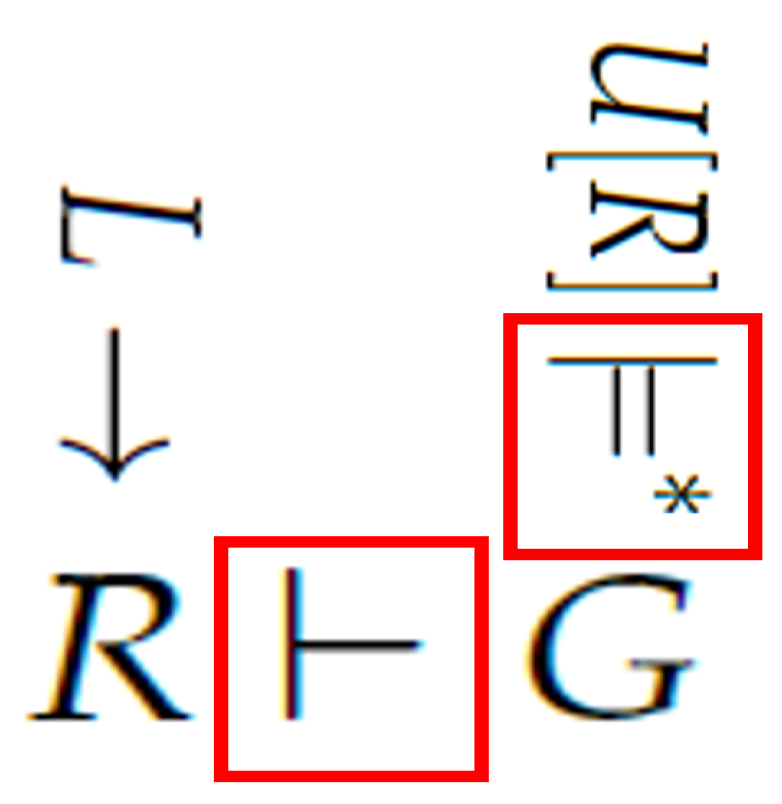

Figure 1 shows our vision of the Neural Tax Networks system. Currently, we are not doing the LLM translations automatically.

This Figure first depicts knowledge authoring as

. Next, one of many natural language queries

U, with its facts, is converted into a first-order formula

G compatible with

R as

. This can be repeated for many different user questions

U. Finally, the system tries to find a proof

. See

Figure 2. The red boxes indicate parts of our processing that may be repeated many times in one user session. This figure highlights knowledge authoring, the semantics of LLMs and logical deduction.

5. Löwenheim–Skolem Theorems

A first-order theory is first-order logic augmented by specific logical rules

Hodel (

1994);

Shoenfield (

1994). Modus ponens deduction for Horn-clauses may be part of a first-order theory. Kunik

Kunik (

2024) gives a downward Löwenheim–Skolem in general terms for several mathematical systems include substitution. These systems describe several deduction methods.

LLMs are trained on many natural language sentences or phrases. Currently, several LLMs are trained on greater than words instances or tokens. LLMs are trained mostly on very recent meanings of words or phrases. Training on recent language keeps LLMs up to date. Also, a great deal of natural language text has recently become available.

Michel, et al.

Michel et al. (

2011) indicates that English adds about 8,500 new words per year. See also Petersen, et al.

Petersen, et al. (

2012). Theorem 5 is based on the idea that new words representing new concepts are added to natural language over time. There are several ways we can represent new concepts: (1) a new concept can be represented as a subset of features, see the features in

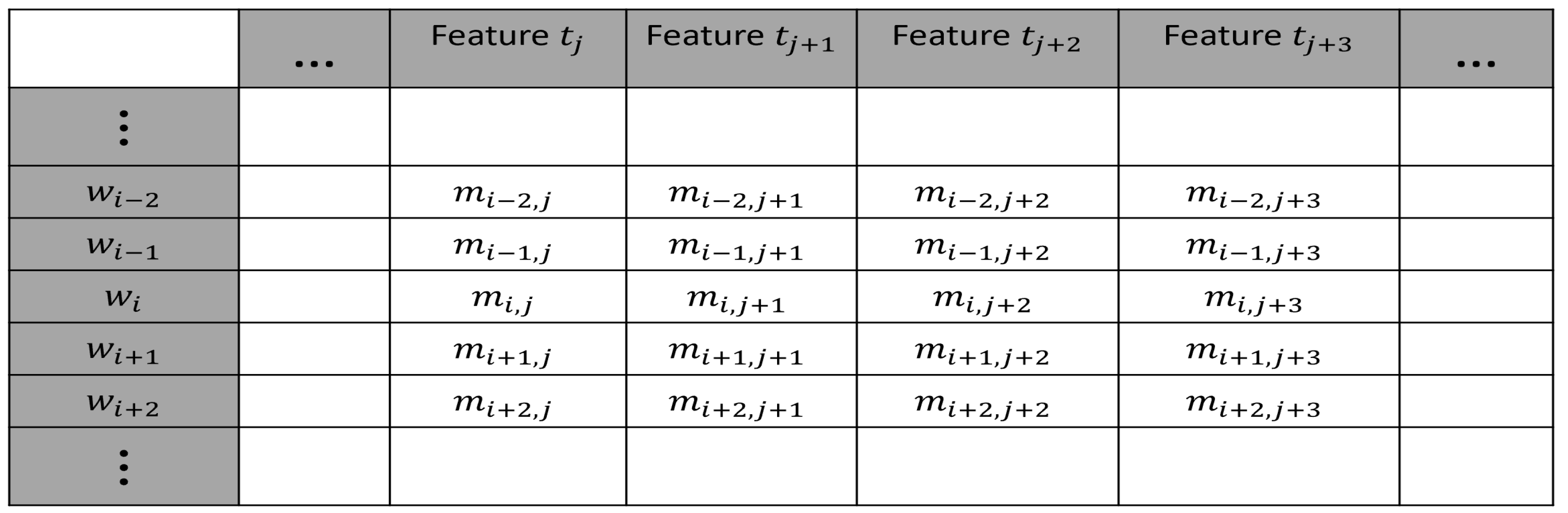

Figure 3, or (2) a new concept may require new features. We assume there will always be concepts that require new features. So the number of columns is countable over all time. Just the same, we assume the number of words is countable over all time. In summary, over all time, we assume the number of rows of words is countably infinite. Also, we assume the number of feature columns is countably infinite.

Given all of these new words and their new features, they diagonalize.

Figure 3 shows a word

that whose features must be different from any other word with a different meaning. That is, any new word representing new concepts

, will never have the same feature values of any of the other words.

Furthermore, in the case of Neural Tax Networks, some of these new words represent goods or services that are taxable. Ideally, the tax law statutes will not have to be changed for such new taxable goods or services. These new words and concepts will supply new logical interpretations for tax law.

Assumption 2. Natural language will always gain new words or phrases. Natural language will ascribe new meanings to existing words or phrases. Some words or phrases will decline in use.

For LLMs, assuming languages always add new words over time, then it can be argued that natural language has an uncountable model if we take a limit over all time. Albeit this uncountable model may only add a few taxable terms each year. To understand the limits of our multimodal system, our assumption is that such language growth and change goes on forever. Some LLMs currently train on at least word instances or tokens. This is much larger than the number of words often used by many theorem proving systems. Comparing countable and uncountable sets in these contexts may give us insight.

For the next theorem, recall Assumption 1 which states the original meaning of words for our theorem-proving system is fixed. In other words, the meaning of the words in law is fixed from when the laws were enacted. These word meanings are models for our theorem-proving system.

Theorem 1 shows context-free grammars can build infinite domains for theorem proving systems. Assumption 2 supposes the set of all words

V in an LLM has cardinality

. So using a similarity measure

s so that each word vector

x has a finite subset of equivalent words

where

, for a constant integer

. Since this uncountable union of finite sets is indexed by an uncountable set,

it must be uncountable.

Theorem 5. Taking a limit over all time, LLMs with constant bounded similarity sets have an number words.

In some sense, Theorem 5 assumes human knowledge will be extended forever. This is because time progresses new concepts will continually be formed. This may be tantamount to assuming social constructs, science, engineering, and applied science will never stop evolving.

The next definition relates different models to each other.

Definition 14 (Elementary extensions). Consider a first-order language . Let and be models and suppose .

Then is an elementary extension of or iff every first-order n-ary formula and n tuple b in , then

If , then is an elementary extension of ,

If , then is an elementary substructure of .

Consider a user input U compatible with a first-order logic rules R of our theorem proving system. These facts and rules are in the set . LLMs may give the semantic expression G where . These formulas G are computed with (e.g., cosine) similarity along with any additional logical rules and facts. This also requires Assumption 2 giving a countable model for G.

Theorem 6 (Löwenheim–Skolem (L-S) Theorems). Consider a first-order language with an infinite model . Then there is a model so that and

Upward If , then is an elementary extension of , or ,

Downward If , then is an elementary substructure of , or .

Corollary 1 (Application of Upward L-S). Consider a first-order language with an countably infinite model for a first-order logic theorem proving system. Suppose this first-order theorem-proving system has a countably infinite domain from a countably infinite model where . Then there is a model that is an elementary extension of and .

Proof. First-order logic theorem proving systems, provided they can encode context free grammars, have countably infinite domains by Theorem 5. So this logical theory has a countable infinite model so that . □

Corollary 2 (Application of Downward L-S). Consider a first-order language and a countably infinite model for a first-order logic theorem proving system. We assume an LLM with and a model so that . By the downward L-S theorem, is an elementary substructure of and .

Proof. Consider a first-order language and a first-order logic theorem proving system with with a countably infinite model . This model can be defined using context-free grammars or a regular language. This genrates a countably infinite domain for the model so .

Suppose we have an uncountable model

based on the uncountablility of LLM models by Theorem 5. That is,

Then by the downward Löwenheim–Skolem Theorem, there is an elementary substucture of where . By Theorem 1 there is an infinite number of sentences in the origional domain of the first-order theorem proving system so . □

This corollary indicates there is a mapping between an LLM’s uncountable model and a first-order logic model for an associated theorem proving system. The downward Löwenheim–Skolem Theorem assumes the axiom of choice. So, unfortunately, there may not be a transition via expanding the similarity measures so each grows to a size that captures the countably infinite model .

In practice, ErgoAI or Prolog theorem provers are used for systems such as ours. Such Prolog-based languages use SLD-resolution. SLD-resolution finds proofs for a set of first-order logic Horn-clauses. It uses unification to substitute interpretations into first-order formulas. Of course, the programming languages ErgoAI, Prolog, and similar languages are Turing complete. This means they have far more expressivity than first-order logic. But, their theorem proving subsystems focus on extended first-order Horn logic. Certainly, first-order logic appears sufficient for encoding and proving results about law.

One of the attractions of SLD-resolution is that it can find proofs for sets of Horn clauses in polynomial time. SLD-resolution is often augmented with negation-as-failure, cycle-detection, or tabling, to forestall infinite cycles. This is useful since Horn logic is semi-decidable, see Theorem 2.

6. Discussion

This paper aims to give a better understanding of relationships between LLMs and first-order logic theorem proving systems. The theorem proving systems we are impelementing are Horn clause resolution logic systems. Particularly, ErgoAI or Prolog. Although the same results will apply to other first-order logic theorem proving systems with similar properties.

The results here assume taking limits over all time. This is an unusual type of limit. Even though all humans are mortal, these results may give insight to their experience due to the large data sets. It is germaine, since LLMs train on very large data sets. Currently, they can be as large as word instances or tokens. In contrast, the number of facts and rules in US tax law requires from to words.

Consider an uncountable model or number of words or concepts from LLMs by Theorem 5. Corollary 2 indicates such an uncountable model can work with a theorem proving system using a countably infinite model. This is very interesting in light of originalism for the law in Assumption 1. Furthermore, many of the rules of tax law are similar to those from 1,900 years ago.

One classical interpretation of the upward Löwenheim–Skolem Theorem is that first-order logic cannot distinguish higher levels of infinity. That is, sets with distinct cardinalities of

, for

. It is also widely discussed that first-order logic cannot make statements about subsets of its domain

Thomas (

1997). Interestingly, regular languages and context-free grammars cannot be expressed strictly in first-order logic

Thomas (

1997). To express context-free grammars in first-order logic, the first-order logic can be augmented to handle subsets of its domain. This may play a role in the philosophical challenges between LLMs and resolution theorem provers.

The Lefschetz Principle of first-order logic

Chang and Keisler (

2012);

Marker (

2002) states that any first-order logic formulas from an

-theory are true when mapped over any closed fields with characteristic 0 and by the field of complex numbers

.

That is, from Definition 14, formulas that can be modeled by fields with characteristic 0 can also be modeled by . A classic example is the algebraically closed field of rational numbers . This field contains the roots of all polynomials with coefficients from . So, contains algebraic numbers that may be complex. Many complex numbers are not roots of polynomial equations with coefficients from . There are a countable number of polynomials with coefficients from , hence . In contrast, . This means sentences that are true in with cardinality are also true in with cardinality .

Finally, our use of the Löwenheim–Skolem Theorems and our discussion of Lefschetz Principle sheds light on origionalism.

7. Conclusions

We presented a high-level description of an expert system for tax law to answer tax questions in natural language based on the tax statutes and case law. Already, the results our proof-of-technolog system produces are fully explainable, i.e. providing a full proofs of the logical reasoning based on a small subset of tax law. We use the first-order logic theorem-proving system in ErgoAI. To effectively achieve complete complete goal, the system will incorporate a data base of all tax laws. It will have an LLM enhanced interface to load the data, translate the questions into logical queries, and translate the generated line of reasoning in natural language. Important theoretical results on the limits of logical reasoning in such systems are presented. Development of expert systems, despite recent advances, is just starting and face many challenges. Some of these challenges are reviewed together with known approaches to overcome them.

References

- Cohen, P. J.; Set theory and the continuum hypothesis, Dover (re-print): New York, 1994.

- Hodel, R. E.; An Intoduction to Mathmatical Logic, Dover: New York, 1995.

- Scalia, A.; Garner, B. A.; Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts, Thomson West, 2012.

- Shoenfield, J. R.; Mathematical Logic, Association for Symbolic Logic: Storrs CT, USA, A. K. Peters Ltd, 1967.

- Chang, C. C.; Keisler, H. J. Model theory, 3rd Edition, Dover 2012.

- Xu, J.; Fei, H.; Pan, L.; Liu, Q.; Lee, M.-L.; Hsu, W. Faithful Logical Reasoning via Symbolic Chain-of-Thought, 2024, arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357v2. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, Q.; Dillig, I; Durrett, G; Satlm: Satisfiability-aided language models using declarative prompting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2024.

- Wei, J.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:24824–24837, 2022.

- Marker, D. Model Theory: An Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, 2002.

- Denis Merigoux,D.; Chataing, N.; Protzenko, J; 2021. Catala: a programming language for the law. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 5, ICFP, Article 77, 2021, 29 pages. [CrossRef]

- Leith, P.; The rise and fall of the legal expert system, European Journal of Law and Technology, Vol 1, Issue 1, 2010.

- Franklin, J.; How much of commonsense and legal reasoning is formalizable? A review of conceptual obstacles, 2012.

- Ebbinghaus, H.D. Löwenheim-Skolem Theorems. Philosophy of Logic (pp. 587-614). North-Holland. 2007.

- Isozaki, I.; Literature review on AI in Law, https://isamu-website.medium.com/literature-review-on-ai-in-law-7fe80e352c34 2024.

- Kirtania, S; Gupta, P.; Radhakirshna, A.; Logic-lm++: Multi-step refinement for symbolic formulations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.02514, 2024.

- Goldshmidt, R; Horovicz, M; TokenSHAP: Interpreting Large Language Models with Monte Carlo Shapley Value Estimation, In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on NLP for Science (NLP4Science) (pp. 1-8). 2024.

- Dixon, M; Bilokon, P.; Halperin, I.; Machine Learning in Finance: from Theory to Practice, Springer, 2020.

- Exploring explainable AI in the tax domain https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10506-024-09395-w (Accessed 2025-06-27).

- Towards eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Tax Law: The Need for a Minimum Legal Standard, 2022.

- Reviewing the explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) and its importance in tax administration https://www.ciat.org/reviewing-the-explainable-artificial-intelligence-xai-and-its-importance-in-tax-administration/?lang=en (Accessed 2025-06-27).

- Katz, S. M. Distribution of content words and phrases in text and language modelling. Natural language engineering. 1996 Mar;2(1):15-59.

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/162 (Accessed 2025-04-28).

- Fast text, https://fasttext.cc/ (Accessed 2025-04-15).

- Bonner, A. J.; Kifer, M. An overview of transaction logic, Theoretical Computer Science 133, no. 2 1994: 205-265.

- Bradford, P. G.; Wollowski, M. A formalization of the Turing Test, ACM SIGART Bulletin 6, no. 4 1995: 3-10.

- Chang, C-L.; Lee, R. C.-T. Symbolic Logic and Mechanical Theorem Proving, Academic Press, 1973.

- Coherent Knowledge: http://coherentknowledge.com/ (Accessed 2025-04-13).

- https://shap.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (Accessed 2025-06-30).

- Duncan-Jones, R. Money and Government in the Roman Empire, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Gao, T; Fodor, P.; Kifer, M; Knowledge Authoring for Rule-Based Reasoning, ODBASE, OTM Conferences, 2018: 461-480.

- Kunik, M.; On the downward Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem for elementary submodels. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03860, 2024.

- Lidz, F.; How to Evade Taxes in Ancient Rome? A 1,900-Year-Old Papyrus Offers a Guide, New York Times, (Accessed: 2025-04-14).

- Michel, J.-B.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, Science 331, 2011, pp. 176–182.

- Nay, J. J; et al. Large language models as tax attorneys: a case study in legal capabilities emergence, 2024, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. [CrossRef]

- Neural Tax Networks: https://neuraltaxnetworks.com/ (Accessed 2025-04-13).

- Orphys, H. A. (assignee); Jaworski, W.; Filatova, E., Bradford, P. G. Determining Correct Answers To Tax And Accounting Issues Arising From Business Transactions And Generating Accounting Entries To Record Those Transactions Using A Computerized Logic Implementation. US 11295393 B1, Published: 2022-04-05.

- Pan, L; Albalak, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. Y. Logic-lm: Empowering large language models with symbolic solvers for faithful logical reasoning, arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12295, 2023.

- Petersen, A. M.; et al. Statistical Laws Governing Fluctuations in Word Use from Word Birth to Word Death, Scientific Reports 2:313, 2012.

- Putnam, H; Models and Reality, The Journal of symbolic logic, 45(3), 464-482.

- Swift, T.; Kifer, M. Multi-paradigm Logic Programming in the ErgoAI System, In Logic Programming and Nonmonotonic Reasoning: 17th International Conference, LPNMR 2024, Dallas, TX, USA, October 11–14, Proceedings. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2024, 126–139. [CrossRef]

- ErgoText System. https://sites.google.com/coherentknowledge.com/ergoai-tutorial/ergoai-tutorial/ergotext (Accessed 2025-06-29).

- 1997, Thomas, W. Languages, automata, and logic. In Handbook of Formal Languages: Volume 3 Beyond Words (pp. 389-455). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 1997.

- Tunstall, L; Von Werra, L.; and Wolf, T. Natural language processing with transformers, O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2022.

- Van Dalen, D. Logic and structure, 4th edition, Universitext, Springer, 2004.

- Wolfram, S. What is chat-gpt doing and Why does it work, Wolfram Media, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).