1. Introduction

The logic of natural language is an old investigation field going back to Aristotile’s logic, the middle-age Scholastic philosophy, and Leibniz’s investigation at the beginning of mathematical logic [34]. In his book about the mathematical analysis of logic [4], George Boole emphasizes the logical basis of natural language. In 1979 Gottlob Frege [13] defined First-order Predicate Logic as a complete conceptual framework. Frege’s language includes predicates of any number of arguments, individual constants and variables, propositional connectives, and quantifiers (universal and existential).

In Principia Mathematica [37], Bertrand Russell and Alfred Withehead introduced the theory of logical types as a remedy to the logical paradoxes discovered within the foundation of mathematics.

In 1928, Alonzo Church introduced the lambda notation, and in 1940 the lambda typed calculus [6]. However, the notion of function, defined by a mathematical formula, goes back to Leonard Euler [10] and Gottlob Frege [13], who realized the functional nature of predicates. Mathematical function resulted in a powerful foundational concept, in mathematical logic, in computability, up to the new frontiers of artificial intelligence [3,6,14,19,23,25,26,31,33,40]. Hans Reichenbach developed a logical analysis of the conversation language in a chapter of his book on mathematical logic [36].

In 1970, Richard Montague wrote the paper “English as a formal language" where typed lambda calculus and high-order logic are combined to represent ordinary discourse, and several papers on the same line followed [9,27,28,29,39].

The elimination of variables is a problem intensively investigated in mathematical logic by many authors, such as Moses Schönfinkel, Harshel Curry, Robert Feys, Alfred Tarski, and Leon Henkin [7,16]. In natural language, neither apparent nor free variables are used, therefore a logical analysis of language has to cope with this phenomenon for a full comprehension of its internal mechanisms. We will show, that this aspect is strictly related to the monadic nature of predicates and the possibility of having high-order predicates.

In [22] a formalism of logical semantics for natural languages was introduced within the High-order Monadic Logic HML, which is essentially a typed lambda calculus based on unary functions with a new logical operator of “Predicate Abstraction" making logical representations of sentences completely adherent to the usual linguistic constructions. In the same paper, an experiment is reported on teaching the given logical formalism to ChatCPT3.5. This shows interesting perspectives on the interaction with chatbots, revealing a surprising ability to use such logical formalism.

In this paper, the approach of [22] is developed, by defining the more complete and motivated formalism of Functional Language Logic (FLL), strictly related to the classical logical analysis of sentences. Any word in a given dictionary is a unary predicate, a function from individuals to truth values. Twenty logical operators express the logical aggregations underlying the main linguistic constructions (Table 23 ).

The functional types for the predicates, individuals, substantives, propositions, hyper-predicates, and ad-predicates are introduced. Hyper-predicates are predicates that apply to predicates and give new propositions, whereas ad-predicates apply to predicates and give new predicates.

The following sections are devoted to specific linguistic phenomena. Direct and indirect complementations are reduced to the application of a complementation operator that, in the case of a direct complementation, takes a substantive, producing a new predicate, while in the case of an indirect complementation, takes an atomic proposition, again giving a new predicate. Modification is the operator transforming a predicate into an ad-predicate.

Predication, complementation, and modification are the main linguistic constructs. Specification is a case of complementation, which is considered apart due to its generality and importance.

Descriptive operators apply to predicates and provide substantives. arguments are then considered.

Finally, operators for managing with context, references, and performatives are considered.

Chatbots, preconceived in [40], are a frontier of artificial intelligence, their acquisition of complex and articulated competencies in dialogic activity with humans confirms the essential role of natural language in constructing the conceptual organization of cognitive systems. Namely, Greeks used the same word, “Logos" meaning either language or reason. This consideration suggests that FLL could be a strategic tool in teaching chatbots to acquire sophisticated competencies in logical analysis [22,24].

In conclusion, a topic for further research is addressed, which is related to the relationship between FFL logical representation of meanings and the embedding vectors of LLM transformers in modern conversational systems.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Logical Symbols and Operators

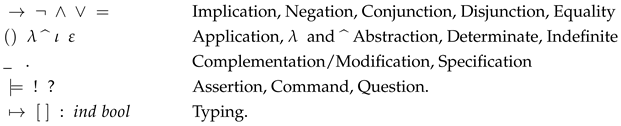

Given an expression

built with operations applied to constant and variables, where the variable

x ranges on the class

A, and taking values in the class

B, we denote by

the function from

A to

B associating to any element

the value

assumed by

when

x takes the value

a. Alonzo Church introduced the lambda notation

to stress that the function does not depend on the chosen variable, we omit the symbol

for a shorter notation. If in

variable

x is replaced by

y (which takes the same values as

x does), for every

a:

therefore:

that is, the two

-expressions are different names for the same function.

A predicate is a symbol denoting a function from a set of individuals to a set of two truth values, we denote by . In the following, we will use predicates with only one argument (monadic) or zero arguments. Monadic predicates are called Properties, while predicates with no arguments are Propositions, which can also be considered symbols for truth values. Letters , possibly with indices, will denote predicates. Symbols , possibly with indices, are individual constants (names of particular individuals), and symbols , possibly with indices, are individual variables. Letters , possibly with indices, are predicate variables.

Symbols , called connectives, are operations on truth values with the following meanings: ; iff ; iff ; iff (whence ); iff .

Symbols , called quantifiers, are operations such that iff ; iff .

Connectives and quantifiers can also be easily seen as operators over predicates, for example, , .

2.2. Abstraction Operators

The operator of class abstraction transforms a monadic predicate P in the class A of the values on which the predicate holds (gives truth value T). This operator was initially defined by Georg Cantor and formalized by Bertrand Russed with the notation . Nowadays, the commonly used notation for classes is .

The notion of type is analogous to that of a class; it is used in many contexts and with many specific senses. We write to denote that a has a type of t. Of course, the elements of a given type provide a class, and analogously, having a type is a property. Therefore, a type can be assimilated into the concepts of class and property, even if its meaning is more related to that one of a symbolic mark to attach to objects for categorizing them.

However, it is useful to distinguish similar concepts because, in many complex analyses, these notions refer to different levels of a discourse that are useful to consider separately. For example, the names of things are different from things in themselves, and operating with names can provide useful possibilities better dealt with in specific contexts by avoiding any confusion with things and operations on them. If and , we denote by the type of ; if A is a class of elements of type t, then we denote by the type of A. Therefore, types can be arranged in expressions of increasing complexity: . The maximum number of nested pairs of parentheses or brackets in the expression of a type provides the logical order of that type.

In 1901, Bertrand Russel discovered a logical paradox related to the intuitive notion of class. Namely, some autoreferential conditions (the class of classes that do not belong to themselves) are contradictory. Axiomatic set theories were developed, which define sets as special classes regulated by axioms, avoiding paradoxes. Type theory, elaborated by Bertrand Russel and Alfred Whitehead, overcomes paradoxes by assigning types for dealing with high-order predicates that apply to predicates as arguments [18]. In natural language, expressions such as or are typical examples of predicates taking predicates as arguments.

Two expressions denoting individuals are equal when they denote the same individual. We can express equality by using monadic properties according to the following trick. We add for every individual

a a predicate

that holds on an individual

b if it denote the individual denoted by

a:

Analogously, a binary operation, such as +, can be expressed by using the monadic operation

, namely:

In this way, an operation’s argument becomes a parameter embedded in a unary operation, giving the same result as a binary operation on two arguments. This phenomenon is crucial in natural language, allowing for a monadic representation of all predicates occurring in linguistic constructions.

The operator of

predicative abstraction allows for raising the logical order of a predicate. If

is a predicate, we denote by

its predicative abstraction, for which:

that is,

is a hyperpredicate (with respect to

), which holds over all predicates that imply

. This means that the implication

becomes the application of a hyper-predicate

telling that

P is an implicant of

, which is different from

, where

a is a loving individual. Namely,

P is a predicate, then it does not love, being

a property of individuals.

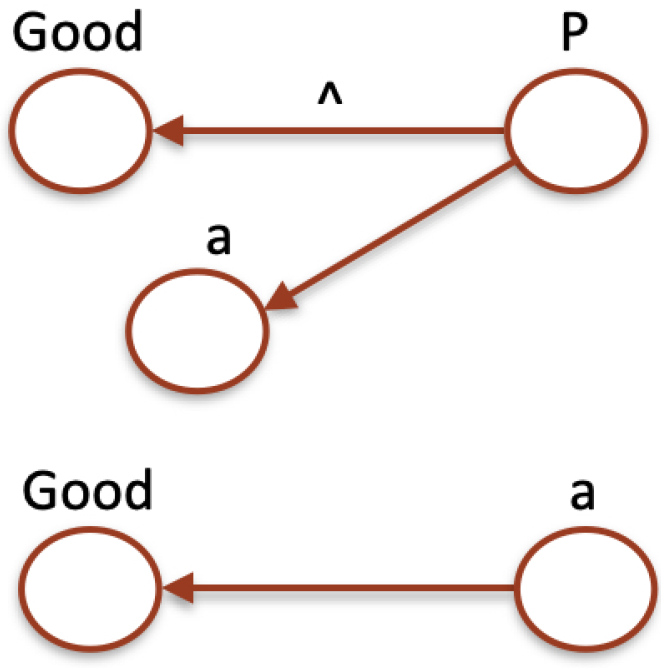

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of the predication Good(a) in a direct way (bottom) and trough predicative abstraction (Top).

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of the predication Good(a) in a direct way (bottom) and trough predicative abstraction (Top).

In the following, we will write for abbreviating because the type raising is implicitly deduced by the argument, which is a predicate rather than an individual.

2.3. Complementation and Descriptive operators

Some other operators will be introduced in the next sections. Two of them change the logical type of expression and correspond to linguistic constructs that change the linguistic category of expressions. They are the complementation operator, denoted by underscore _, and the specification operator (a special case of complementation) denoted by a suffix-dot. The other two operators are descriptive because tale predicates and provide substantives. They are determination operator, due to Giuseppe Peano [35], and choice operator, due to David Hilbert [18] complete our list.

2.4. Comparison with Related Logical Formalisms

Many formalisms are aiming at representing sentences logically. After the mentioned approach inaugurated by Richard Montague, in many fields, such as logic, linguistics, philosophy, computer science, knowledge representation, and other related fields, the search for logical representations coupling rigor with simplicity and adequacy was always very active and oriented to many specific requirements of some applicative contexts. In the setting of logical approaches, let us mention the works in the context of the CSLI (Center for the Study of Language and Information), especially the Situation Logic, the Natural Language Semantics, and the intensional logic [2,8,11,12]. For many aspects, FLL has common features with these approaches, but two important characteristics distinguish it properly. It is directly related to the traditional logical analysis of the discourse, which is very popular in the educational curricula, especially in the context of classical dead languages (Greek, Latin); moreover, it is based on a limited number of logical symbols applied to the words of fixed dictionaries, which makes it very simple to learn, even without entering in its complex logical basis.

The formalism of FLL is concerned with the logical representations of sentences. However, for completeness, we want to mention some topics that are important in logical formalisms but outside the scope of the paper. One of these topics is concerned with formal deductions (Proof Theory), realized by suitable deductive algorithms; the other refers to the interpretations of formulas within mathematical structures (Model Theory) [6,18,21,38].

The first logical calculus was elaborated for Predicative Logic by Gottlob Frege for Predicate Logic [13]. This logic has constant and individual variables, predicative constants denoting relations of any number of arguments on individuals, together with connectives and quantifiers. Frege’s predicative calculus, and many other equivalents to it, resulted to be complete, that is, it can deduce all the logical consequences deriving from a list of axioms. A logical consequence of a set of propositions is a formula true in all the models where the propositions of are true.

In Model Theory, a model M is associated with a class of formulae (a theory) when all the formulae of , according to suitable interpretation rules, are true in M. For Predicative Logic, a fundamental result, known as Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem, holds according to which any coherent theory (where ⊥ cannot be deduced) can be interpreted in the domain of natural numbers [6,18].

3. Results

Let us assume that all words of a given language, in our case, English (written with capital initial letters), are monadic predicates of some logical order. Sometimes, for a better reading of complex formulas, we will use the inverse parentheses notation by writing instead of .

3.1. Categories and Functional Types

The formalism FLL has the following categories of expressions, and some of them will receive some types:

1) Arguments, of type , is the category of any expression that occurs as an argument of a function;

2) Individuals, of type , is the category of denotations of costants , which can be considered as indexes o indicals of objects assumed in a discourse;

3) Propositions, of type , is the category of denotations of truth values, also seen as predicates of zero arguments. An expression is an atomic proposition, or a simple predication while , for example (Eat and Drink)(a), where the predicate is the conjunction of two predicates, or , which is the conjunction of two propositions, are not atomic predications. We will indicate by the type of atomic propositions;

4)

Predicates, of type

, is the category of monadic predicates, that is, functions from arguments to truth values:

in this category predicative constants

are included;

5)

Hyper-predicates, of type

, is the category of predicates that apply to predicates and provide propositions:

hyper-predicates can be considered second-order predicates, and analogously, third-order predicates can be considered and, in general, higher-order predicates for further levels;

6)

Ad-predicates, of type

, is the category of functions that apply to predicates and provide predicates:

7) Substantives, of type , is the category of individuals, predicative constants, and any expression that can be equated to them. Also, capital letters denoting classes (possibly with indexes) are substantives. Equating an expression to a constant provides a substativation;

8) Logical Operators are the symbols expressing operations on predicates;

9) Performatives are the symbols expressing discourse functionalities.

In the sequel, we provide examples of FLL representations for small texts in the natural language (English). From these representations, twenty logical operators emerge that can describe the meaning of these texts by composing the meanings of the single words. In this reduction, we get the comprehension of texts from the predicates associated with the lemmas of a dictionary.

We want to recall that the usual grammatical categories of Verbs, Nouns, and Adjectives are based on spatiotemporal features. Adverbs realize hyper predicates on predicates (negation, intensification, modality, …). At the same time, the other linguistic units are “empty words", having meanings driven by the contexts in playing roles that correspond to logical operators of FLL.

3.2. FLL Representation of Simple Sentences

Let us start with a simple sentence: “John is good." Its FLL representation is given in

Table 1.

John is a person name, then John(a) means that there is an individual a who saisfies the property of having the name “John", and a satisfies the property “Good".

The sentence “John loves Mary" has the FLL representation given in

Table 2.

Here a new operator appears, with postfix notation, indicated by _ and called of

complementaton, which transforms a predicate, such as Love, into the predicate Love_(b), completing the meaning of Love with the object

b. When Love_(b) applies to the individual

a we get (Love_(b))(a), or simply Love_(b)(a), expressing “a love b". Therefore, complementing a monadic predicate, we express a binary predicate. In general, given a predicate

, the expression

is a function of three possible types, according to the following list:

the example above falls in the first case and is called

direct complementation; the second case is called

indirect complementation; the third case is called

modification, or with traditional terminology,

predicative complementation.

For a better reading of formulas, we avoid application parentheses after _ in complementations, and we assume that the complementation operator applies with left priority. Firstly, the leftmost operator applies, then the operator _ following it on the right, and so on, up to the rightmost complementation operator. In this way, in the usual notation , the subject of the predicate is at the end, on the right, while in the inverse parentheses notation , the subject is at the beginning on the left.

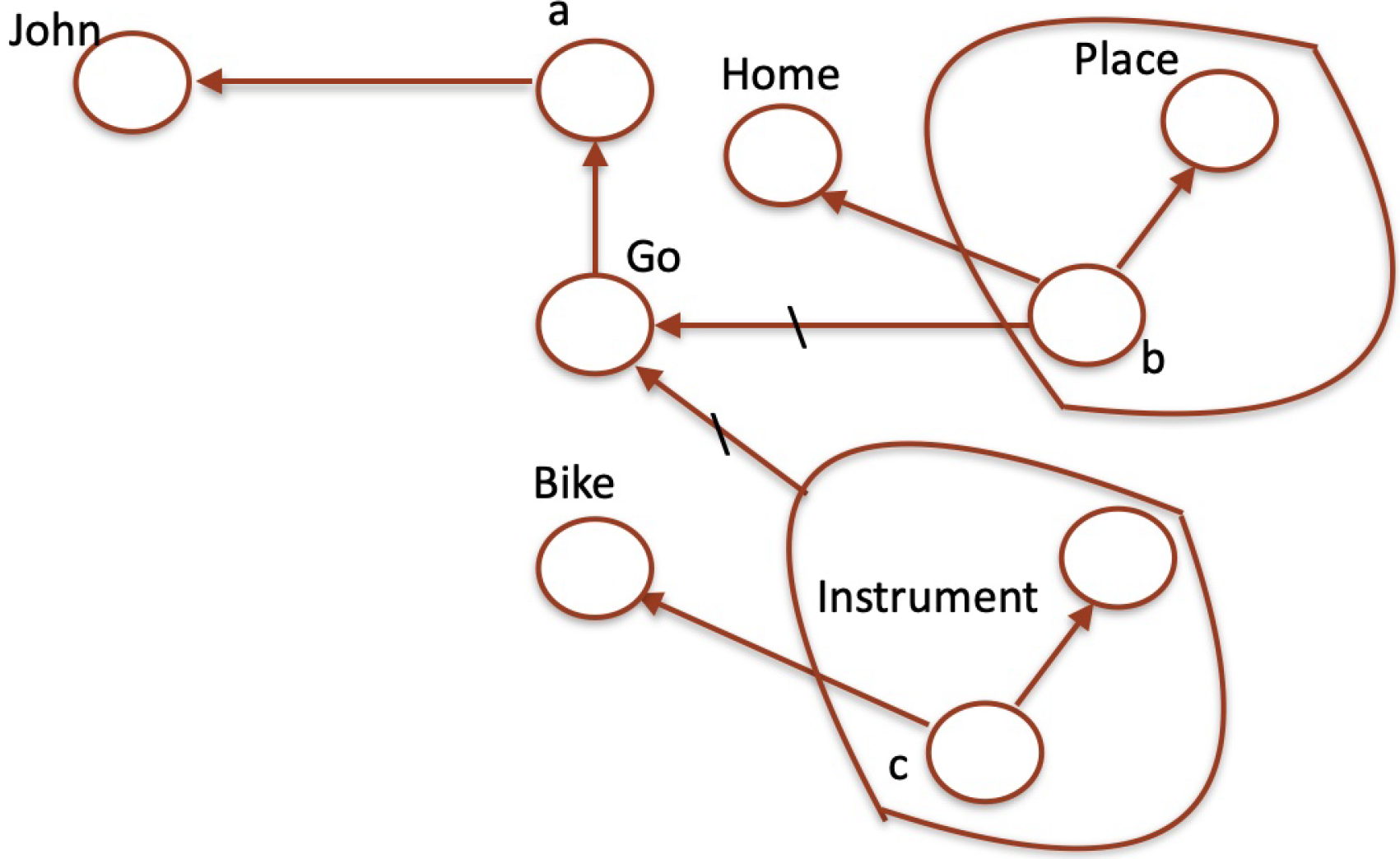

The sentence “John goes home with a bike" has the representation given in

Table 3.

in this representation, the operator _ transforms Go into Go_, a function taking an atomic proposition and producing a predicate. Analogously Go is a predicate to which the operator _ applies, and Go takes as an argument and becomes Go. In conclusion, the resulting predicate applies to the individual a providing a proposition. Atomic propositions Place(b) and Instrument(c) define the roles of complements which complete the predicate .

Figure 2 visualizes the representation of

Table 3 by a labeled graph: constants or words label nodes. Simple arrows denote predication, while labeled arrows express the operator indicated in the label. We remark that the graph is a second-order graph (in more complex cases, third or fourth orders are necessary) because there are nodes including subgraphs (represented by surrounding curves)

A different way of expressing complementation is through arguments that are sequences, as in

Table 4. However, the method based on the complementation operator is more adherent to the linguistic mechanism of complementation therefore, in the sequel, we follow it.

3.3. Complementation

Traditional linguistic analysis is focused on a long list of possible complements: object, specification, place, time, instrument, …. In a list used in the schools, it is possible to find fifty different types of complements. However, such lists result, to a large extent, arbitrary and incomplete. The linguistic form of complementation depends on specific syntactic features. In a logical representation, it is important only to identify the elements completing a predicate by distinguishing each one from the others. Let us consider the sentence “John gives a pen to Mary." The following FLL representation of this sentence is given in

Table 5.

However, different predicates (Take, Accept, Destination, Target) could be used instead of "Receive" to adequately express the role of constant c, apart from specific syntactical realizations of the sentence.

The sentence “People elected John as major" is represented in

Table 6.

3.4. Specification

The specification is a frequent kind of indirect complementation, putting in some relationship a predicate with a substantive (membership, inclusion, pertinence, possess, …). It is useful to introduce for it a special symbol:

completing

with the argument

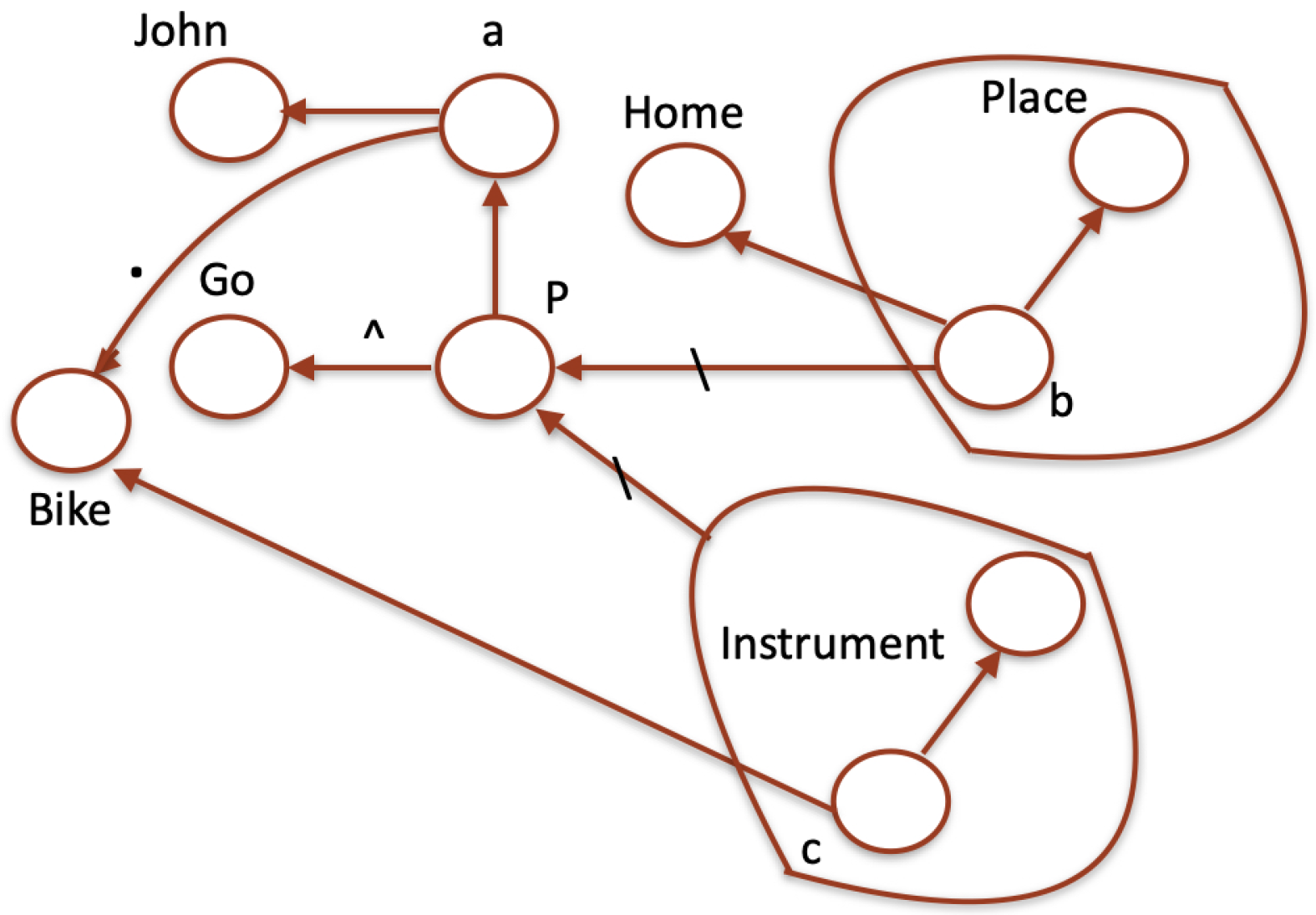

a as a specification complement. The sentence “John goes home with his bike" is given in

Table 7 where a predicate constant

P and predicative abstraction is used.

Figure 3 visualizes this FLL representation (in the following examples the symbol of predicative abstraction will be tacitly intended).

The sentence “John asked Mary for information on the train timetable" is in

Table 8.

The dot notation for specification suggests reducing all cases of indirect complementation to specification (in some languages, such as Arabic, there are only the object complement and the specification complement). For example, “John goes home with his bike" is represented in

Table 9 using the specification operator for expressing complementation.

A more complex example is the sentence “Yesterday I was walking without shoes", in

Table 10, which has a complex ad-predicate realized by modifications.

These examples show clearly that the same sentence can be represented in many ways. Each representation has advantages or inadequacies concerning the others. The right choice depends on the kind of the intended application of the representation.

3.5. Modification

In the previous examples, we used the modification operator to transform a predicate into an ad-predicate. The typical case ad-predicates are the adverbs modifying verbs, or special verbs, such as begin, finish, interrupt, can, will, must, appear, seem, …, are modifiers of other verbs, as it happens in the representation of

Table 13.

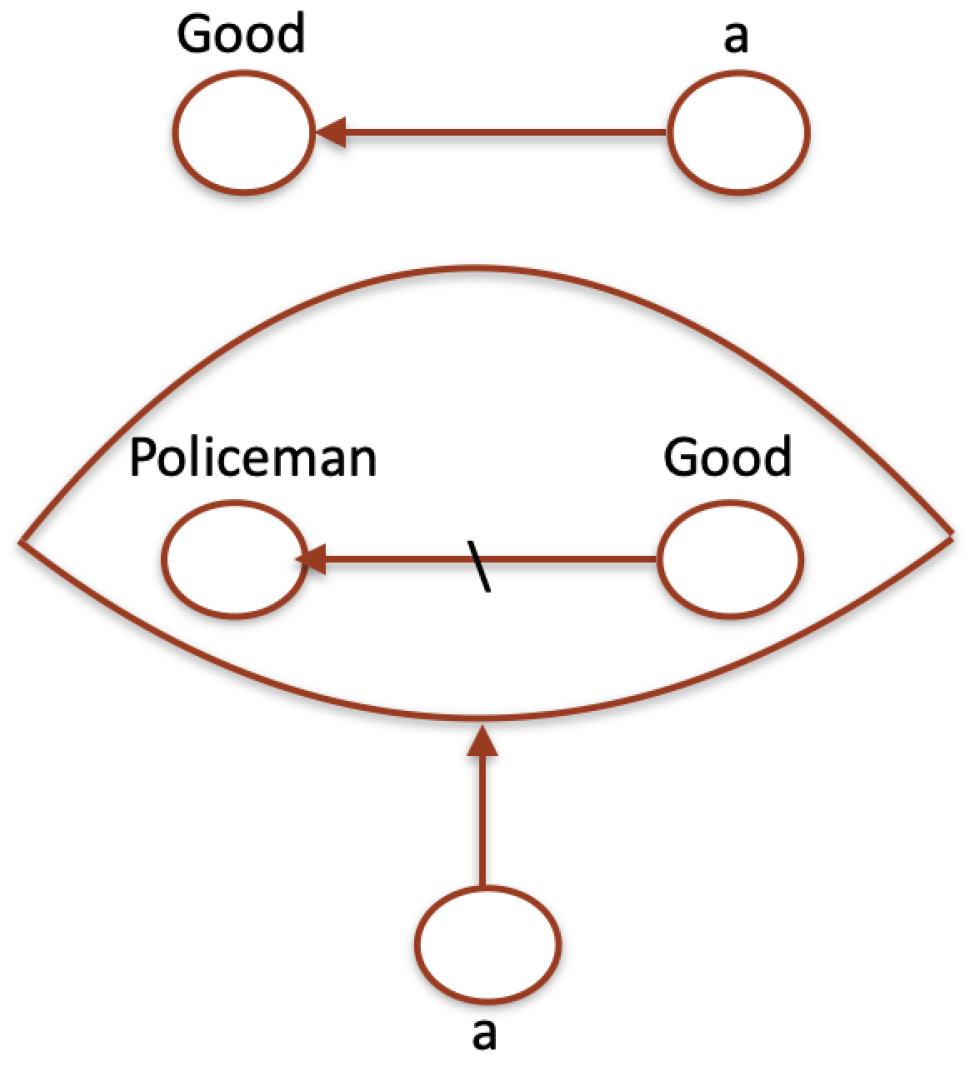

An analogous modification occurs when a noun or adjective modifies an adjective, as it is shown in

Table 14, and

Figure 4.

of course “John is good" and “John is a good policeman" use “good" in two completely different ways, making it evident that the same word, in different contexts, can exhibit different logical types. Namely, in the first case, Good is a predicate, while in the second one, it is an ad-predicate.

3.6. Determiners, Indefinites, Plurals

The

operator of

determination was introduced by Giuseppe Peano [35]. Let

P be a predicate that is satisfied only by one individual; then, this individual is denoted by

. Hence:

The expression corresponds to the definite article of natural languages. If we write , we mean that in the given context, a boy is univocally determined and is identified by the individual constant a. If more than one value satisfies P, all the propositions where occurs are false.

The

operator

choice has been introduced by David Hilbert [18], it provides a chosen

indefinite value that satisfies

P. If no argument satisfies

P, all the propositions where

occurs are false. Hence:

and:

Using

we can put:

Operators

and

have both type

.

Different occurrences of may denote different individuals. If we say Any man who loves a woman is happy, we refer to an indefinite man. If we say that Any man who loves a woman is happy, but any man who does not love any woman is searching for a woman whom he can love, clearly, the two occurrences of “any man" have to denote different persons. Otherwise, the sentence is meaningless.

Proposition implies the following propositions, where constants cover all the values satisfied by P:

…

Therefore, the choice operator provides universal quantification and the constructions distributing the values of a predicate over other predicates (every man is mortal).

We can extend

notation with numeric indexes so that

expressions with the same index denote the same individual. In this way, expressions such as

can be used as usual variables. For example, lambda expressions can be expressed by:

Indefinite values expressed by expressions are different from generic indeterminate values that, in many languages, correspond to undeterminate articles. In FLL, particular values are denoted by individual constants. Namely, when we write , we mean that there exists a value that satisfies P, and we call it a.

Relative clauses are of two kinds: descriptive e restrictive. If we say “John, who lives in Rome, will not come to the meeting", the relative clause (introduced by who) adds information that can be equivalently given by saying: “John will not come to the meeting, he lives in Rome".

Conversely, “John is searching for a pen that writes green" is a restrictive relative clause because characterizes what John is searching for. The FLL representation of

Table 15 is obtained using the choice Hilbert operator.

Now we give an example using the operator to express a consecutive construction.

“The bag is so heavy that I cannot bring it" in FLL provides the representation of

Table 16.

In the last equation applies to the predicate within parentheses, and Greater_c’(c) means that: “The weight c (of the bag) overcomes , which is any weight that a can bring.

In FLL numerals: 0, 1, 2, …(in decimal notation) and ordinals: , with the usual symbols of arithmetic operations and relations, are available.

Modification with numerals (0, 1, 2, …) allows for a simple representation of plurals. Given a predicate , the expression means a couple of individuals that satisfy . Analogously, denotes a plurality of individuals satisfying .

Modifications such as denote ordinals (“the second which satisfies Pred") assuming an order, specified by the context or previously given. For example, the following is a representation that refers to two boys; the first speaks, and the second listens:

––––––––––––––––––

Speak(b)

Listen(c)

––––––––––––––––––

3.7. Contexts, References, and Performatives

Deixis (Greek etymology) refers to all the aspects of a sentence’s spatiotemporal context. Words such as this, that, now, I, and you are deictic words assuming meanings that refer to their specific context. A situation consists of all elements necessary to the correct meaning of a sentence, including deixis and other aspects, such as presuppositions that a speaker assumes about the persons, things, facts, and habits on which a specific communication is based. Moreover, other aspects regarding persons involved in communication can be relevant, and in many languages, these aspects can remarkably influence the expressions used. The register (familiar, formal, institutional, …), especially in some languages, can direct even the choice of the words of sentences.

Anaphora (Greek etymology) refers to the linguistic elements pointing to words and expressions already occurring in sentences in the linear order of their generation. Pronouns are the typical elements playing this role. The concordance is the mechanism on which anaphora is based. Moreover, the same mechanism is also responsible for the aggregation of linguistic expressions in bigger units, including them as components.

Concordance is realized using grammatical marks expressing features (gender, number, person, time, …). The system of grammatical features can change in different languages (form, color, localization, distribution, consistency, …). A pronoun can be seen as an aggregation of marks. In this way, it refers to the closest linguistic expression preceding it and having the same marks. Grammatical features alter linguistic forms using inflection and conjugation so that elements with the same marks are aggregated in bigger units.

In the FLL representations, the individual constants realize pronouns, while parentheses realize aggregation. If we consider the complexity of phenomena realizing anaphora and concordance, we can appreciate FLL’s great advantage over natural languages.

A class of sentences widely analyzed by logicians since the Middle Ages are donkey sentences, so-called for an example reported in an ancient treatise of logical analysis of language (Every man who owns a donkey will beat). The problem with these sentences is the pronoun reference in the context of a universal quantification.

The sentence “Every man loves the woman who loves him". In predicative logic becomes:

where a reference hereditates the distributive nature of the referred term (

).

If we express universal quantification with the

operator, we get:

where iota operator refers to the individuals chosen on the left of implication. Using

with indexes:

however, a form more adherent to the linguistic form and using once

is the following:

“Any man loved by a woman loves her", which we can also represent by

Table 17 and

Table 18 (the choice is intended in the class of substantives).

Let us consider the sentence “The boys were entering two at a time." Traditional logical analysis tells us that “two at a time" is a complement of "distribution." However, this does not completely clarify its underlying logical mechanism, which is completely represented in

Table 19.

The values of change with the choices within the class A, and for each pair, there is an entrance time.

We can further explicit the distribution process. Let be the choices and the choices (covering the boys and the times). Then, the FLL representation is equivalent to the sequence of propositions:

…

It is important to remark on the continuative character of the verb “were entering" because it tells us that the process is developed in a time interval along a sequence of steps. Therefore, the distribution expresses a modality of realization of the process associated with the verb enter.

Table 20 shows the associated FLL representation.

which we can read: “The boys were entering distributing in two". In this way, we are very close to the linguistic form of the sentence through an analysis of the deep structure of the sentence.

Coordination and subordination between propositions consist of predications over propositions. In the sentence: “While the boys were entering the classroom, the teacher was writing on the blackboard", a relationship expressed by while" occurs between propositions

representable by the predication:

where:

The boys were entering the classroom;

The teacher was writing on the blackboard.

Conjunctions of temporal and situational nature (concessive, adversative, consecutive, final, causal, …) express relationships in typical subordinative clauses.

An FLL representation can be always expressed by a predication such as , where all the specific information about P and a are given in the remaining part of the representation. In a sense, all the components of the sentence representation converge into . We may use the assertion symbol ⊧ to stress this special role. In the linguistic terminology, means that is the principal proposition of the sentence, to which the other propositions refer in determining their subordinative relationships.

Languages allow for describing facts but also giving commands, and asking questions.

Performatives are linguistic elements responsible for indicating the specific functionality of statements. We give only two examples in FLL here: "Go home!" and "Where do you go?" of

Table 21 and

Table 22, respectively.

The interrogative symbol before the assertion symbol tells us that the expression is a question and the same symbol before the constant confers to the constant the role of the interrogative pronoun. Analogously the exclamation mark expresses orders and before the constant it indicates the individual to which the order is directed.

In conclusion, the FLL logical representation of language is based on predication with predicate and arguments at different logical orders. The presence of different logical orders provides the main complexity of linguistic expressions. When people learn to speak, they implicitly acquire the capability of analysis and synthesis that allows for correct and efficient use of the integrated system of predications underlying FLL representations. Three of four logical orders are very often present in the ordinary discourse (“your beauty fascinates me").

Logical symbols of FLL can be reduced to 20. No variable symbols are present, but individual constants

. possibly indexed, and predicative constants

or class constants

(possibly indexed).

Table 23 summarizes all FLL operators.

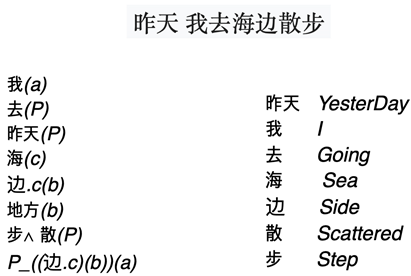

Table 24 will show the interlingual character of FLL representations.

4. Conclusions

The adequacy of FLL in representing the logic of natural languages highlights, in terms of mathematical logic, the role of traditional logical analysis developed within the classical linguistic tradition, linked to the study of ancient languages and based on Aristotile’s schema of predication. Namely, FLL logically puts on a rigorous basis the main concepts on which logical analysis is built by using twenty logical operators (Table 23). In this sense, the logic of the natural language results in a link between mathematical logic and linguistics, and also a natural way to approach the first using the second one. The monadic nature of FLL is a crucial aspect concerning the elimination of variables, coupled with the use of high-order predicates.

In previous work, conversations with ChatGPT were reported, which show the ability of these systems to learn a logical formalism similar to FLL and acquire the capability of providing correct logical representations of given texts. However, we know these chatbots are based on transformers, and then linguistic meanings are reduced to embedding vectors, as numerical vectors of many thousands of components.

The idea of an embedding vector is rooted in a long linguistic tradition [15], which emerged in the 20th century, with the origin in structural linguistics concerning phonology, where a phoneme is a set of pertinent features that exclusively identify it in opposition to all the other phonemes of a language. The same intuition can be exported to word semantics because, given a document corpus, a word can be identified by all the documents where it occurs and by all the positions where in these documents it occurs.

A further investigation could be focused on the relationship between embedding vectors for sentences and discourses and their corresponding FLL representations. The two methods correspond to (geometric) synthetic versus (logic) analytic comprehension. Specific aspects of a detailed analysis of their comparison could provide crucial elements for a deep understanding of the related cognitive process on which knowledge is based [24].

Mathematical logic, with the notions of class, symbol, number, variable, operation, equation, relation, function, predicate, set, type, proposition, truth value, connective, variable abstraction, and predicate abstraction provides a powerful and universal system of conceptualization, which surely is one of the most relevant successes of mathematics. Teaching chatbots mathematical logic could improve their semantic mechanisms by acquiring theoretical competencies in their internal knowledge organization.

A line of development of the paper could be the analysis of chatbot interactions in learning and exhibiting FLL representations, along with the experience presented in [22]. The levels, times, and strategies of FLL training could provide tools for evaluating the logical competencies of future conversational systems.