1. Introduction

Long COVID, known as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), is a condition characterized by persistent symptoms that continue for weeks or months after the acute phase of a COVID-19 infection [

1,

2,

3]. Long COVID affects millions of individuals worldwide, with varying degrees of severity and duration [

3,

4]. A systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted the complexity of Long COVID, noting that symptoms can span multiple systems, including neurological, cardiopulmonary, and gastrointestinal [

4]. A recent study also revealed a significant shift in healthcare utilization among Long COVID patients, moving from acute care to outpatient services [

5]. This transition reflects the chronic and relapsing nature of Long COVID, which often requires prolonged symptom management rather than emergency intervention. As a result, the condition poses a growing burden on primary and specialty outpatient care, challenging healthcare systems with increased demand for multidisciplinary support. This shift underscores the urgency of developing effective, scalable, and evidence-based treatment strategies that can be delivered in outpatient settings to improve patient outcomes and reduce long-term healthcare costs [

6].

Recent studies on Long COVID have provided significant insights into the condition's complexity and impact of viral loads on symptoms. In particular, the higher viral loads were associated with more severe respiratory symptoms and restrictive spirometry patterns in recovered individuals [

7]. Moreover, slower viral clearance rates during the acute phase, more severe initial symptoms, and underlying chronic conditions or immune dysregulation were linked to an increased risk of Long COVID, particularly among women [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Additionally, research has shown that persistent viral presence can lead to prolonged immune activation, contributing to the chronic symptoms observed in Long COVID patients [

12].

Importantly, the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—even in the absence of active viral replication—has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Long COVID. Circulating spike protein has been detected in plasma months after initial infection, suggesting it may act as a persistent antigenic stimulus, contributing to ongoing immune activation and chronic inflammation [

13,

14]. Studies have shown that the spike protein, particularly the S1 subunit, can remain in the body for extended periods, contributing to ongoing immune activation and inflammation [

15]. This persistent presence of the spike protein has been linked to various Long COVID symptoms, including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and neurological issues [

16]. Some patients with Long COVID were found to have SARS-CoV-2 proteins in their blood months after the initial infection, indicating a potential mechanism for the chronic symptoms observed [

17]. Additionally, prolonged detection of spike protein in plasma or immune cells is found to be associated with sustained inflammation and ongoing symptoms, suggesting it may serve as a predictive biomarker for post-acute sequelae [

13,

14]. Monitoring spike protein dynamics could therefore enhance early identification of at-risk individuals and inform targeted intervention strategies [

10]. These findings underscore the relevance of spike protein as a quantitative biomarker for risk assessment and potential therapeutic targeting in Long COVID.

Moreover, research has also highlighted the significant relationship between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the production of proinflammatory cytokines in Long COVID patients [

18]. The spike protein has been shown to trigger prolonged expression of cell adhesion markers and the release of various cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), which are commonly observed in severe COVID-19 cases [

18]. This persistent inflammatory response is thought to contribute to the chronic symptoms experienced by Long COVID patients. Additionally, the spike protein can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages, leading to the release of tissue factor-bearing microvesicles and further promoting inflammation [

19]. Another study highlighted a persistent change in blood proteins, suggesting that an overactive immune response might be a contributing factor [

20]. In addition, higher levels of leukocytes were found to be associated with more severe symptoms in older women [

21]. These findings suggest that the spike protein plays a crucial role in sustaining the inflammatory environment that underlies many of the long-term symptoms associated with Long COVID.

Despite the substantial current findings on investigating the role of spike protein in influencing Long COVID symptoms and expression of preinflammatory cytokines, its systematic characterization in Long COVID patients using mechanistic approaches remains limited. We thus aimed to explore the role of spike protein in Long COVID by investigating the dose-dependent effects and temporal profile based on the developed mathematical models. Therefore, the objectives of this study are fourfold: (i) characterize the dose-response relationships of spike protein on Long COVID symptom numbers and release of proinflammatory mediators, (ii) quantify the time-dependent spike protein concentration in Long COVID patients, and (iii) provide a comprehensive risk assessment strategy with the developed dose-response tools and mathematical modeling to facilitate personalized monitoring and early therapeutic interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Data and Framework

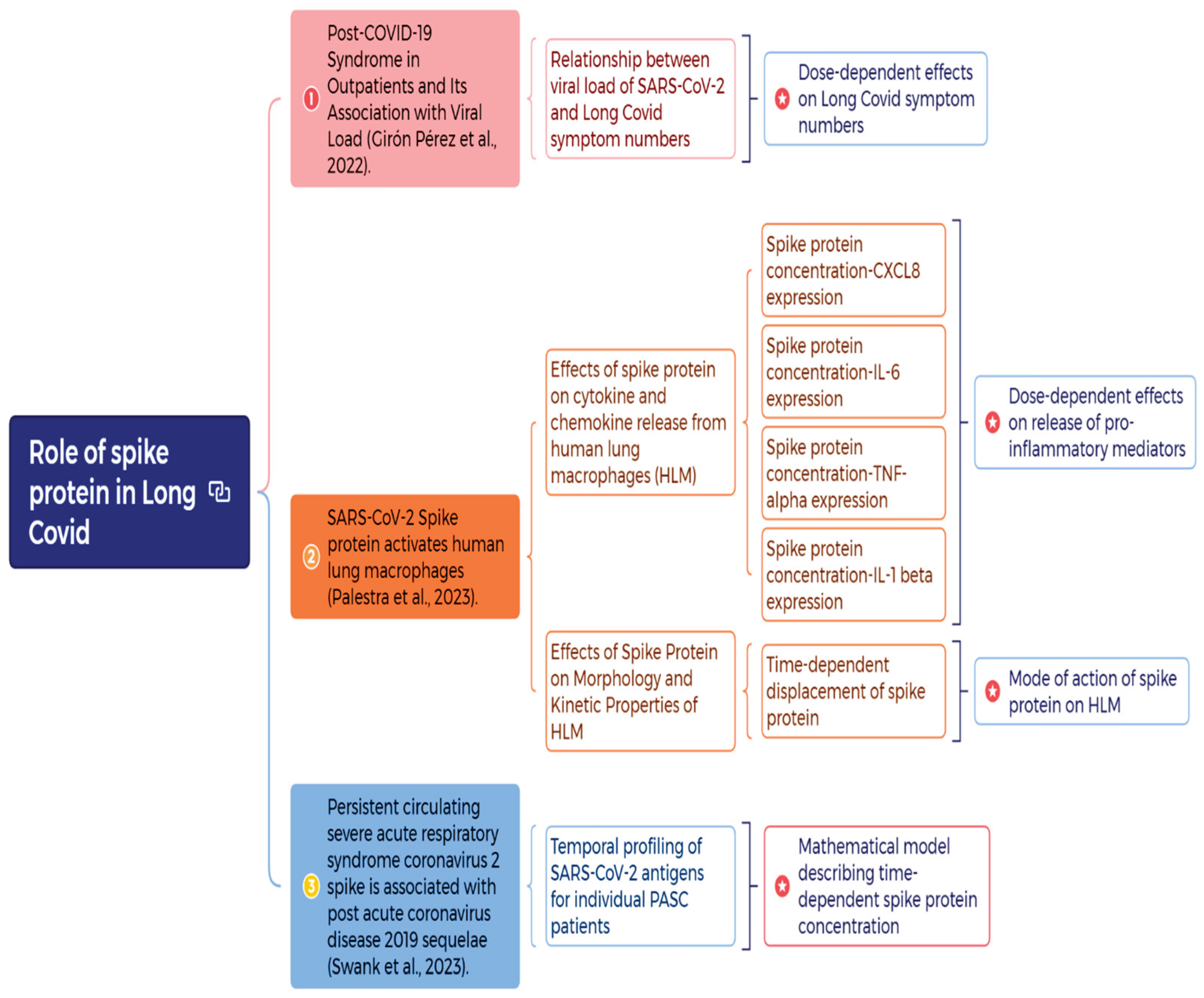

To develop risk assessment strategies by mechanistically investigating the role of spike protein in Long COVID, we adopted three studies to explore both dose-dependent and time-dependent profiles of spike protein in PASC patients [

22,

23,

24] (

Figure 1). For dose-dependent effects, the relationships between spike protein concentration−Long COVID symptom numbers and spike protein concentration−expression of proinflammatory mediators were constructed [

22,

24]. The spike protein dynamic monitoring for individual PASC patients [

23] was also mechanistically described with the developed mathematical model. The mode of action of spike protein on Human Lung Macrophages (HLMs) was also discussed [

24].

2.2. Dose-Response Model

We constructed the dose-response relationships for spike protein concentration (log copy μL

-1) versus Long COVID symptom numbers (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) [

22] and expression of proinflammatory mediators [

24] by fitting the three-parameter Hill model to datasets of the published literature as:

where

D is the spike protein concentration (log copy μL

-1),

Emax is the maximum Long COVID symptom numbers or fraction of protein expression compared to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 1 µg mL

-1,

ED50 is the dose causing an effect equal to 50%

Emax (symptom numbers or fraction of protein expression), and

n is the fitted Hill coefficient. The Hill model provides a robust and interpretable framework for modeling sigmoidal dose-response relationships, which are commonly observed in biological systems involving receptor-ligand interactions and inflammatory signaling. This model allows us to quantitatively characterize the potency (

ED50) and steepness (

n) of spike protein–induced effects, facilitating comparison across datasets and enabling a more mechanistic understanding of dose-dependent symptom manifestation and cytokine activation in Long COVID.

2.3. Time-Dependent Modeling of Spike Protein Concentration

To characterize dynamic changes of spike protein in Long COVID patients, data points of measured spike protein concentrations were extracted and cluster analysis was applied to group patients with similar temporal patterns of spike protein levels [

23]. The optimal number of clusters was determined using a scree plot, which evaluates the within-group sum of squares (WSS) to identify the point at which adding more clusters results in diminishing returns on variance explained. The time-dependent spike protein concentrations were then fitted with a nonlinear statistical model:

D=a+b

t2+ce

t+d

t/ln

t where

D is the spike protein concentration (log copy μL

-1),

t is time (month), and a, b, c, and d are fitted coefficients.

2.4. Data Analysis

Mathematical model fittings with uncertainties were conducted by using the TableCurve 2D (Version 5.01, AISN Software, Mapleton, OR, USA). Cluster analysis was conducted by using the cluster package in R language (Version 4.1.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3. Results

3.1. Effect Analyses on Long COVID Symptom Numbers

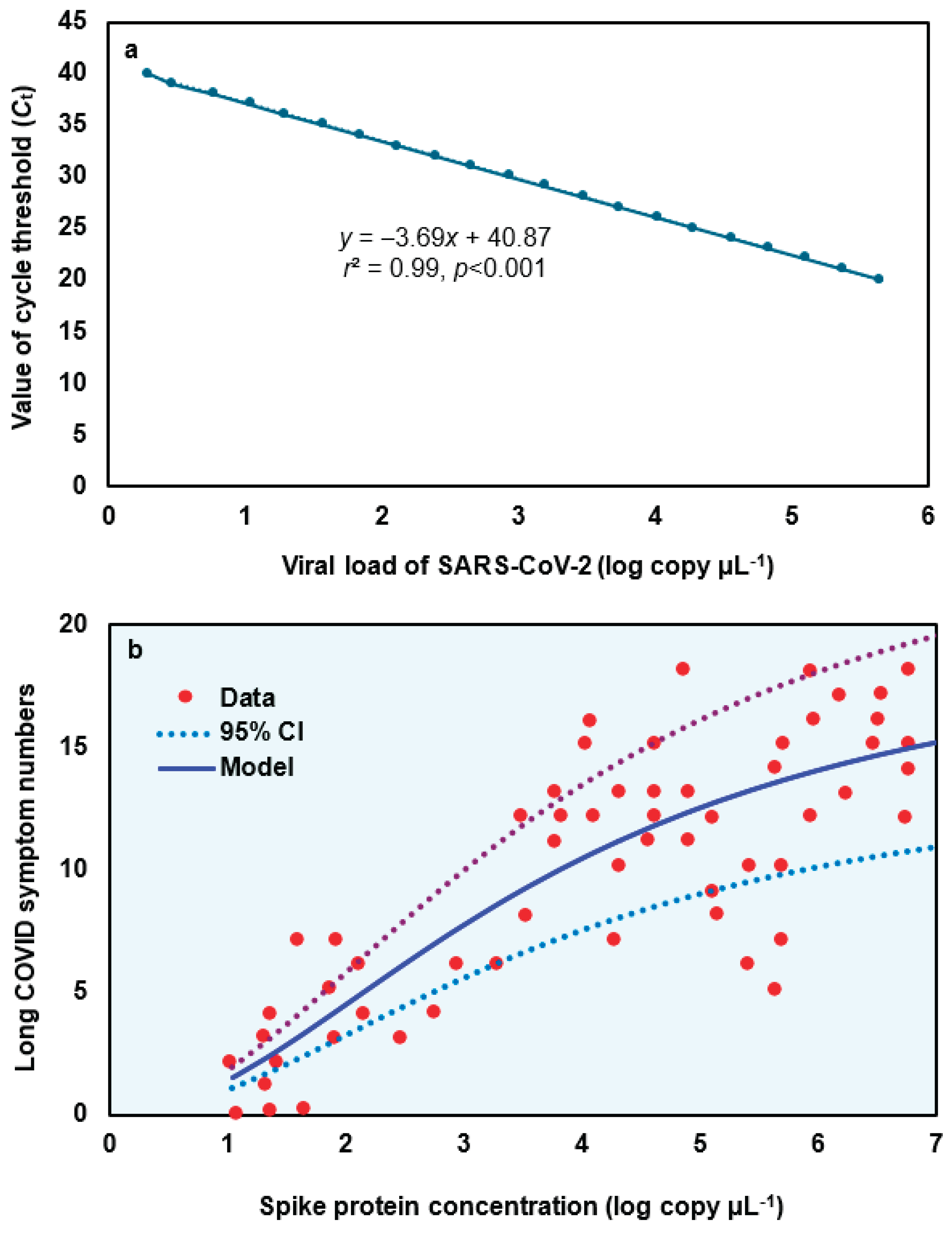

To construct the relationship between spike protein concentration (log copy μL

-1) and Long COVID symptom numbers, a linear fashion between value of cycle threshold (

Ct) and the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 based in Gene E was firstly developed (

y=−3.69

x+40.87,

r² = 0.99,

p < 0.001;

Figure 2a;

Table S1). Subsequently, a three-parameter Hill-based model was also applied to assess the relationships between spike protein concentration (log copy μL

-1) and Long COVID symptom numbers (

Figure 2b;

Tables S2 and S3). Results showed that the Hill-based model could mechanistically inform Long COVID symptom number based on spike protein (

r2 = 0.7,

p < 0.001) with mean

Emax of 19.83 and

ED50 of 3.77 log copy μL

-1 (

Table S3).

3.2. Time-Dependent Modeling of Spike Protein Concentration

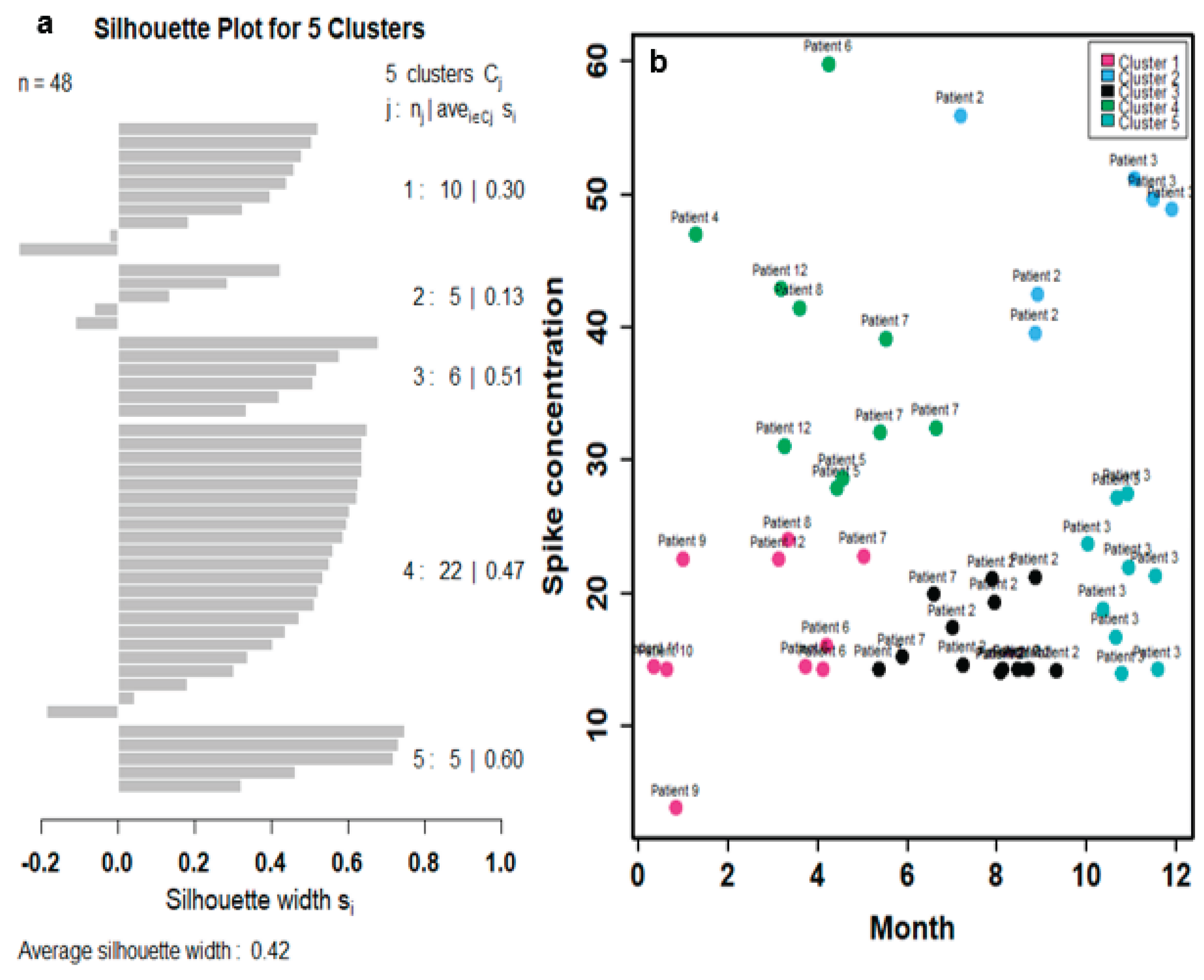

To better reflect the relationships between time and spike protein concentration in twelve Long COVID patients (

Figure S1), a cluster analysis was first performed to group similar data points into clusters based on k-means clustering. Five clusters were characterized based on the result of within-group sum of squares (SS) (

Figure S2). The silhouette plot indicates that the five-cluster solution provides moderate overall validity (mean silhouette width = 0.42) (

Figure 3a). Most spike protein concentration data have positive coefficients, typically between 0.1 and 0.6, signifying that they are better matched to their assigned cluster than to any other. This suggests heterogeneity in spike protein levels among Long COVID patients, potentially reflecting different underlying biological mechanisms or symptom profiles. Thus, the 48 data points by the twelve Long COVID patients can be characterized by the 5 clusters in the time-spike protein concentration relationship (

Figure 3b). Points from clusters 1, 2, and 4 are positioned very close to the convex hull boundaries of neighboring clusters, indicating potential overlap or proximity in feature space. As a result, these boundary observations exhibit negative silhouette widths (

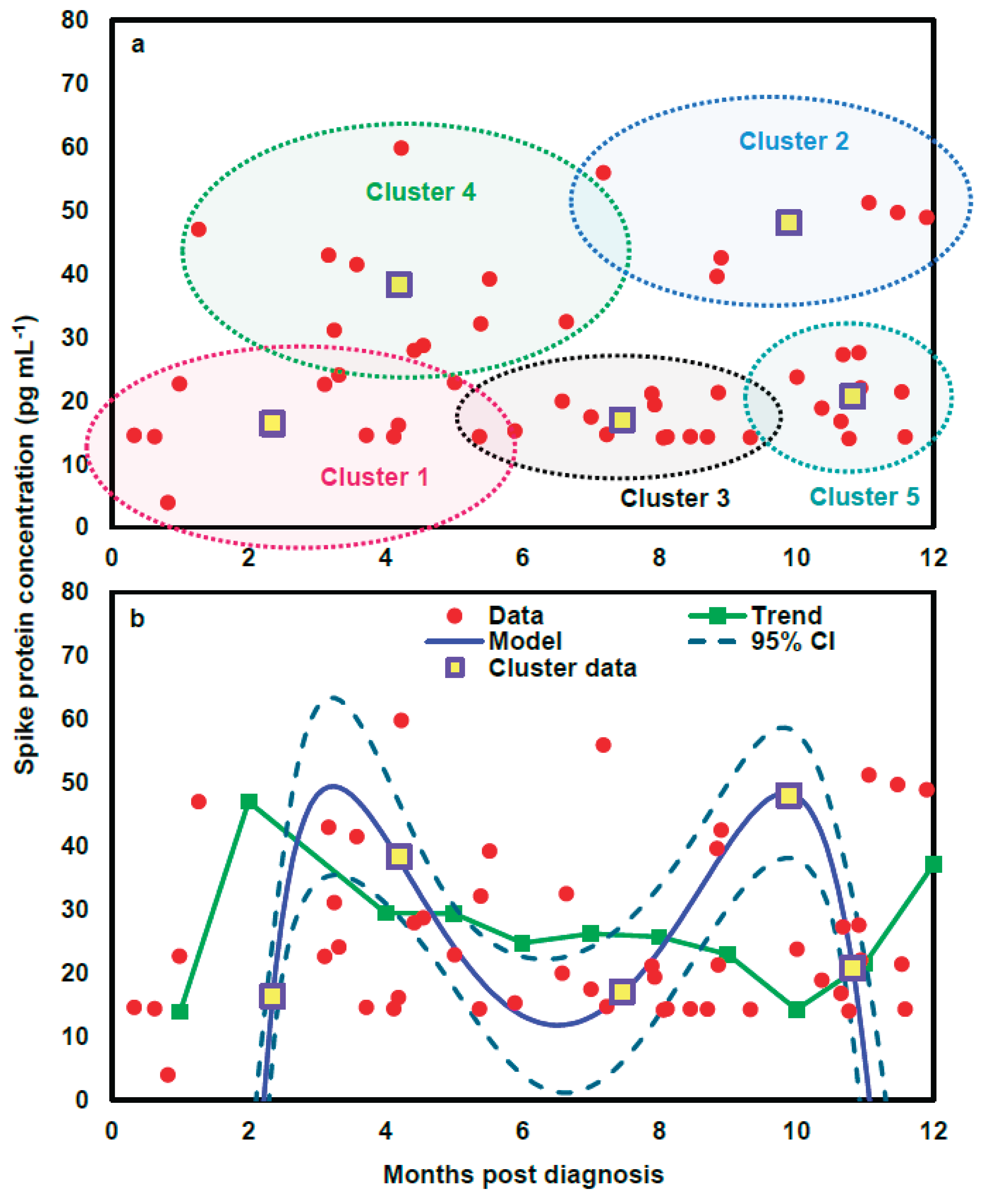

Figure 3a). Subsequently, a mathematical model was applied to project the time-dependent spike protein concentrations (

Figure 4). We showed that the distributions of the 48 data points under the five clusters were appropriately grouped (

Figure 4a). We further indicated that the time-dependent spike protein concentration changes in patients had a well-statistical fashion (

r2=0.99;

p<0.001) with a trend analysis (average spike protein concentration in each month) as a comparison (

Figure 4b;

Table S4).

3.3. Dose-Response Between Spike Protein and Proinflammatory Mediator Expression

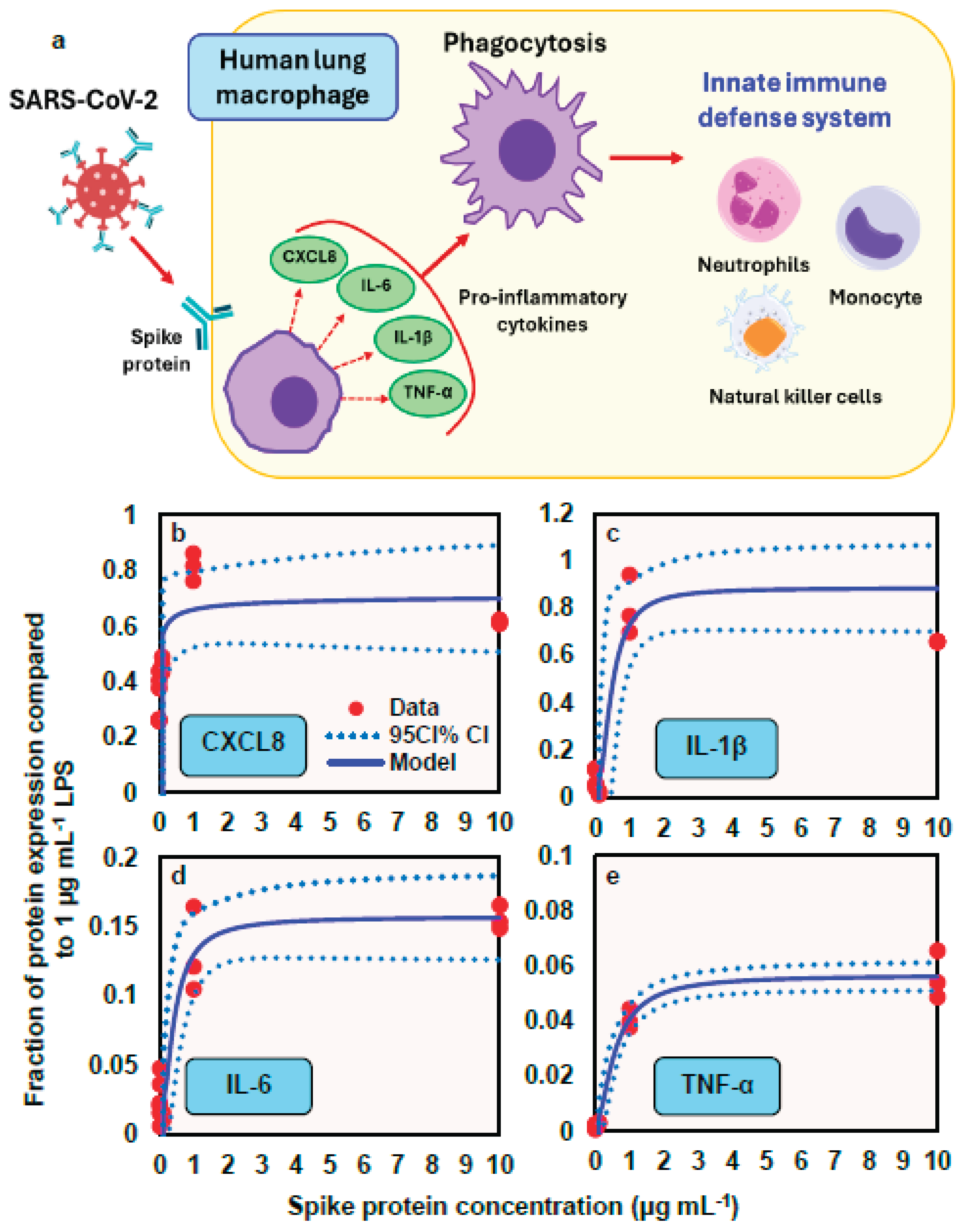

A conceptual model illustrates how spike protein induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) and chemokine (e.g., CXCL8) from human lung macrophages (HLMs), thereby promoting phagocytosis that contributes to innate immunity (

Figure 5a). This response is followed by the recruitment of various inflammatory cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and natural killer cells. To describe the relationships between spike protein concentration and expression of proinflammatory mediators (fraction of protein expression compared to LPS at 1 µg mL

-1), a three-parameter Hill-based model was applied (

Figure 5b − e). Our results indicated that the Hill-based model could appropriately inform the nonlinear proinflammatory mediators−spike protein relationships (

r2 = 0.38 − 0.98,

p = 0.001− 0.06) (

Figure 5b − e;

Table S5). We showed that among the four proinflammatory mediators, IL-1β presented the highest mean

Emax of 0.88, followed by CXCL8 (0.72), IL-6 (0.16), and TNF-α (0.06), whereas CXCL8 had the lowest

ED50 of 0.01 μg mL

-1, followed by IL-6 (0.39), IL-1β (0.46), and TNF-α (0.56) (

Figure 5b − e;

Table S5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Spike Protein in Long COVID Patients and Its Effects

Recent studies have identified the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in the blood of individuals suffering from Long COVID, suggesting it may be a biomarker and potential contributor to prolonged symptoms [

25]. A study revealed that spike protein was detectable in a majority of Long COVID patients up to 12 months after their initial infection, despite the absence of active viral replication [

23]. These residual spike proteins are hypothesized to evade immune clearance and remain in monocytes or other tissues, serving as a chronic immunogenic stimulus. This persistent antigen presence is strongly associated with systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation, including T cell activation and cytokine production. Furthermore, patients with detectable spike protein tend to report more severe or prolonged symptoms, including fatigue, cognitive impairment, and cardiovascular irregularities. This finding points toward a mechanism involving viral protein persistence—rather than ongoing infection—as a driver of chronic symptoms. They also proposed that spike protein may remain due to reservoirs of virus in tissues such as the gastrointestinal tract, releasing viral components intermittently into the bloodstream. Similarly, the temporal change of any Long COVID symptom also showed a steep decrease initially (from 92% at acute phase to 55% at 1-month follow-up), followed by stabilization at approximately 50% during 1-year follow-up [

26].

The presence of spike protein has important implications for immune system dysregulation. It has been shown to act as a superantigen, triggering excessive immune activation and potentially contributing to autoimmunity and persistent inflammation [

27]. This sustained immune response can result in a cascade of symptoms commonly reported in Long COVID, such as fatigue, brain fog, and cardiovascular issues. The interaction of spike protein with toll-like receptors and other immune pathways may also lead to the production of cytokines and inflammatory mediators, creating a chronic inflammatory state [

28]. Notably, studies also observed that patients with early post-acute immune dysregulation—marked by interferon-γ persistence and complement system activation—were more likely to experience sustained high spike levels [

15]. These findings underscore the biological plausibility that circulating spike protein plays an active role in the development and maintenance of Long COVID pathology, possibly through mechanisms of chronic immune activation, endothelial injury, and localized tissue inflammation.

Furthermore, spike protein has been associated with vascular and neurological effects that may underlie many Long COVID manifestations. Evidence suggests that it can disrupt the blood-brain barrier and impair endothelial function, leading to neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction [

29]. Additionally, studies have indicated that spike protein may contribute to microclot formation and platelet activation, which have been documented in Long COVID patients and are thought to impair oxygen delivery and tissue perfusion [

30]. These pathological mechanisms support the hypothesis that circulating spike protein is not merely a remnant of infection but an active participant in the disease process of Long COVID.

4.2. Role of Proinflammatory Mediators in Long COVID

Proinflammatory mediators play a central role in the pathophysiology of Long COVID by perpetuating immune activation and tissue damage long after the resolution of acute infection. Elevated levels of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) have been consistently reported in patients with persistent symptoms, suggesting a chronic inflammatory state [

31]. This prolonged cytokine response may result from immune dysregulation initiated during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including impaired interferon signaling and incomplete resolution of inflammation. These mediators can contribute to systemic symptoms such as fatigue, myalgia, and neurocognitive impairment by affecting the central nervous system, promoting endothelial dysfunction, and interfering with cellular energy metabolism [

32].

In addition to cytokines, other proinflammatory molecules such as C-reactive protein (CRP), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been implicated in the persistence of symptoms and tissue remodeling in Long COVID [

33]. These biomarkers are often elevated in individuals experiencing cardiovascular and respiratory complications, suggesting ongoing vascular inflammation and damage. Furthermore, prolonged activation of innate immune cells, including monocytes and macrophages, can sustain this inflammatory environment, creating a feedback loop that prevents immune homeostasis. Understanding the role of these pro-inflammatory mediators not only clarifies the underlying biology of Long COVID but also opens the door to targeted therapies, such as anti-cytokine treatments or immunomodulators, to mitigate long-term sequelae.

Escalating concentrations of recombinant spike can activate human lung macrophages, triggering production of proinflammatory cytokines that mirror the "cytokine storm" signature observed in clinical COVID-19 cases (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CXCL10) [

34,

35]. Our dose-response analysis on the changing chemokine/cytokine levels included monocyte/macrophage (CXCL8), proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6), and cytokines that promote innate and adaptive immune response (IFN-γ and TNF-α). Notably, serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α serve as significant predictors of disease severity and mortality [

31], with IL-6 being particularly abundant in severe cases and potentially mediating neuropsychiatric symptoms in Long COVID [

36,

37]. Spike-mediated immune escape mechanisms amplify inflammasome-triggered pyroptosis and damage-associated molecular patterns release, overactivating macrophages and natural killer cells beyond physiological antiviral responses [

38].

On the other hand, cytokine profiles differ between acute and Long COVID, with acute cases showing elevated IL-6 levels while Long COVID patients exhibit increased IL-2 and IL-17 [

38]. Individuals without persistent symptoms have higher IL-6, IL-10 and IL-4. The injection-induced multisystem inflammation syndrome (MIS) presents inflammatory risks comparable to those triggered by viral infection. Proinflammatory cytokines have been detected in serum following Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination, with certain monocyte populations undergoing epigenetic conditioning that results in enhanced cytokine production (particularly IFN-γ, CXCL10, and TNF-α) upon booster vaccination [

35]. While both COVID-19 and MIS patients exhibit similar activation of the coagulation cascade and elevated LDH levels, these biomarkers are absent in Long COVID patients, suggesting distinct pathogenic mechanisms [

39]. Future research must focus on differentiating between infection-derived and injection-derived spike protein exposure to enable accurate risk assessment and proper attribution of inflammatory outcomes.

In addition, dysbiotic microbiome-induced proinflammatory microenvironment can promote SARS-CoV-2 entry via angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor-2

(ACE2), serine transmembrane TMPRSS2 and possibly other non-canonical pathways [

40]. SARS-CoV-2 infection alters the oral microbiome, deteriorating oral health and playing a role in the development of Long COVID [

40]. Dysbiotic microbiome in Long COVID patients leads to decreased short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria (

Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus,

Dorea, and

Bifidobacterium), impaired enteroendocrine cell function, and increased gut permeability, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

41]. A recent study also found that the number of platelet-leukocyte aggregates is significantly associated with residual lung damage that sustains the most frequently referred symptoms, such as dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue at rest and after exertion [

42]. Long COVID patients show a unique pattern of platelet activation, along with low-grade inflammation mainly driven by C-reactive protein and IL-6, which is linked to the level of platelet activation.

4.3. Implications for Long COVID Risk Assessment

The growing understanding of Long COVID’s complex pathophysiology has significant implications for improving risk assessment frameworks. Risk assessment of Long COVID involves identifying factors that predispose individuals to develop persistent symptoms following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerging research suggests that a more holistic approach—integrating demographic, clinical, immunological, and psychosocial factors—can better predict who is at risk. For instance, in a large cohort study from the UK, the presence of more than five symptoms during the first week of infection strongly predicted the risk of developing Long COVID [

43]. Studies also showed that women, older adults, and individuals with pre-existing conditions such as asthma or autoimmune diseases are more likely to experience Long COVID [

26,

43,

44]. Additionally, a high symptom burden in the early phase of COVID-19, particularly fatigue, headache, and shortness of breath, is strongly associated with long-term complications [

26]. These findings highlight the need for early identification and stratification of at-risk individuals based on a multi-dimensional set of predictors.

Furthermore, immunological and genetic predispositions are increasingly recognized in risk stratification. For example, individuals with delayed clearance of viral RNA and early reactivation of latent viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus were more likely to experience Long COVID symptoms [

45]. This suggests that immune system dysregulation may underlie some long-term complications. Low levels of certain immune markers, like interferon-γ and IL-2, during acute infection were associated with poor recovery and symptom persistence [

45]. Incorporating biomarkers such as persistent viral antigens, pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, CXCL8), and immune cell dysregulation into risk assessment models can significantly enhance their predictive power. Persistent elevations in inflammatory mediators known as IL-1β and TNF-α have been correlated with symptom duration and severity.

These immunological indicators, when further integrated with clinical and demographic data, can form the basis of a precision medicine approach to Long COVID risk assessment. Such an approach could facilitate proactive monitoring and tailored treatment to inform public health strategies for managing the long-term impacts of pandemic. To expand on the predictive utility of immune indicators, our study establishes a mechanistic risk assessment strategy based on spike protein concentrations and multiple inflammatory biomarkers, including CXCL8, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. By quantifying spike protein levels in patient samples and correlating them with symptom severity and inflammatory profiles, our approach enables early identification of high-risk individuals and offers a mechanistic basis for interventions aimed at preventing or alleviating Long COVID manifestations.

Psychosocial and environmental factors also contribute to Long COVID risk. Individuals with high levels of psychological stress, depression, or socioeconomic disadvantage are more susceptible to prolonged symptoms [

46]. These elements may affect both the immune response and access to timely healthcare, exacerbating risk. As a result, effective risk assessment of Long COVID requires a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates medical, biological, and social determinants. Early identification of at-risk individuals can facilitate closer monitoring and early intervention to prevent or mitigate long-term impacts.

Long COVID represents a significant health burden that current National Health Services (NHS) services are unlikely to meet, emphasizing the urgent need for new care delivery models that enable rapid patient access [

47]. The growing health and economic impact of Long COVID, assessed through disability-adjusted life years and quality-adjusted life years, may already surpass that of other chronic conditions and is expected to increase further with ongoing COVID-19 infections [

47]. In this context, the integration of comprehensive risk assessment tools into healthcare pathways becomes crucial to optimize care delivery and resource allocation. Identifying individuals at higher risk for developing Long COVID—based on demographic, clinical, and biological indicators—can facilitate earlier intervention, targeted monitoring, and more efficient use of specialized services.

To manage the escalating burden of Long COVID, healthcare systems must adopt integrated, multidisciplinary care models that incorporate validated risk stratification frameworks. Such models could involve primary care providers using standardized screening tools to assess risk profiles—including factors such as symptom burden during acute infection, comorbidities, sex, age, and biomarker levels—to determine the need for referral to post-COVID clinics or specialist care [

48,

49]. Furthermore, a comprehensive mechanistic model incorporating antibody pharmacokinetics and deep mutational scanning and regional genomic surveillance data could compute how much and how long a recovery from a recent infection with a SARS-CoV-2 variant will protect against another variant, enabling to predict future variant dynamics and to inform risk assessment of variants and vaccine design [

50]. This proactive approach would improve clinical outcomes by enabling earlier diagnosis and intervention, reducing unnecessary referrals and service bottlenecks. Furthermore, centralized data systems linking risk profiles with longitudinal outcomes can help refine predictive models, inform dynamic resource planning, and guide research priorities.

In addition to improving patient-level care, risk assessment also has broader socioeconomic implications. By predicting who is most likely to experience long-term disability, health systems can anticipate impacts on workforce participation, disability claims, and mental health service demand. Modeling studies suggest that targeted early interventions based on risk prediction can significantly reduce long-term healthcare costs and productivity losses [

51]. Therefore, the integration of Long COVID risk assessment into national care strategies can enhance individual care pathways to provide a critical tool for managing the wider public health and economic consequences of the pandemic.

5. Conclusions

A structured risk assessment strategy for Long COVID is vital for enabling early intervention and optimizing healthcare resource allocation. The constructed dose-response relationship between spike protein concentration and disease symptoms, including proinflammatory effects, can be used as a predictive tool for Long COVID risk assessment. The time-dependent spike protein modeling can be incorporated with the most sensitive proinflammatory mediator (CXCL8) as a biomarker for preventive measures. By quantifying spike protein levels in patient samples and correlating them with symptom severity and inflammatory biomarker profiles, clinicians can identify individuals at higher risk for persistent symptoms. This relationship allows for stratification of patients into risk categories, facilitating personalized monitoring and early therapeutic interventions. Our work provides a mechanistic basis for targeting treatments aimed at reducing spike protein load or mitigating its downstream inflammatory effects, potentially preventing or alleviating Long COVID manifestations. Additionally, to strengthen preparedness for further outbreaks of post-viral conditions, future studies can build on the standardized risk assessment research, be inclusive of other crucial mediators, for patients suffering from Long COVID.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Figure S1. Raw data of temporal profiling of SARS-CoV-2 spikes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) patients (n=12). Figure S2. Scree plot showing variabilities (within groups sum of squares) in clusters. Table S1: Experimental data of relationships between cycle threshold Ct value and SARS-CoV-2 viral load concentration (log copy µL

-1) adopted from Girón Pérez et al. [

18]. Table S2. Experimental data of relationships between SARS-CoV-2 viral load concentration (log copy µL

-1) and symptom numbers after COVID-19 infection adopted from Girón Pérez et al. [

18]. Table S3. Fitted coefficients (mean ± S.E.) of three-parameter Hill model describing symptom numbers of Long Covid corresponding to different viral loads. Table S4. Fitted coefficients (mean ± S.E.) of mathematical model (y=a+bx

2+ce

x+dx/lnx) describing months post diagnosis-dependent spike concentration (pg mL

-1). Table S5. Fitted coefficients (mean ± S.E.) of the three-parameter Hill model describing fraction of protein expression compared to LPS (1 µg mL

-1) in human lung macrophage treated with different spike protein concentrations

Author Contributions

Y.-F.Y.: Conceptualization, Collecting data, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft. M.-P.L.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. S.-C.C.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. Y.-J.L.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. S.-H.Y.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. T.-H.L.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. C.-Y.C.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. W.-M.W.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. S.-Y.C.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. I.-H.L.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. H.-A.H.: Methodology, validation, review and editing. C.-M.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Republic of China under Grant NSTC 113-2313-B-002-032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated for this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. CDC, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/long-term-effects/index.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Datta, S.D.; Talwar, A.; Lee, J.T. A proposed framework and timeline of the spectrum of disease due to SARS-CoV-2 infection: illness beyond acute infection and public health implications. JAMA 2020, 324, 2251–2252. [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Greenwood, D.C.C.; Smith, T. Long COVID as a long-term condition. BMJ Med. 2025, 4, e001366.

- Natarajan, A.; Shetty, A.; Delanerolle, G.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Raymont, V.; Rathod, S.; Halabi, S.; Elliot, K.; Shi, J.Q.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Long COVID symptoms. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 88. [CrossRef]

- DeVoss, R.; Carlton, E.J.; Jolley, S.E.; Perraillon, M.C. Healthcare utilization patterns before and after a Long COVID diagnosis: a case-control study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 514. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.D.; Ingram, J.; Sculthorpe, N.F. More than 100 persistent symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 (Long COVID): A scoping review. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 750378. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, U.; Ahmed, I.; Afshan, S.; Jogezai, Z.H.; Kumar, P.; Ahsan, A.; Rehan, F.; Hussain, N.; Faheem, S.; Baloch, I.A.; et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral load on restrictive spirometry patterns in mild COVID-19 recovered middle-aged individuals: A six-month prospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1089. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C.; Antar, A.A.R.; Broach, J.; Wright, C.; Stamegna, P.; Luzuriaga, K.; Hafer, N.; McManus, D.D.; Manabe, Y.C.; Soni, A. Relationship between acute SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance and Long COVID symptoms: A cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80, 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Darley, D.R.; Wilson, D.B.; Howe, A.; Munier, C.M.L.; Dore, G.J.; Kelleher, A.D.; Matthews, G.V. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 210–216. [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deitchman, A.N.; Torres, L.; Iyer, N.S.; Munter, S.E.; Nixon, C.C.; Amlani, A.; Takahashi, S.; Aweeka, F.; Hoh, R.; et al. Long-term SARS-CoV-2-specific immune and inflammatory responses in individuals recovering from COVID-19 with and without post-acute symptoms. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109518. [CrossRef]

- Notarte, K.I.; Catahay, J.A.; Velasco, J.V.; Ver, A.T.; Santos de Oliveira, M.H.; Macaranas, I.; Khan, A.; Pastrana, A.; Barh, D.; Bernal, M.J.R.; et al. Impact of viral load on severity of COVID-19 and long COVID: A systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3061–3072.

- da Silva, S.J.R.; de Lima, S.C.; da Silva, R.C.; Kohl, A.; Pena, L. Viral load in COVID-19 patients: Implications for prognosis and vaccine efficacy in the context of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022, 8, 836826. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Espín, E.; Tebbutt, S.J. Association of SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence with long COVID. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 504–506. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.K.; Guevara-Coto, J.; Yogendra, R.; Francisco, E.B.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Mora, J.; Rojas, L.; Hlaing, A.; Sutter, K.; et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840150. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Lim, E.Y.; Metaxaki, M.; Jackson, S.; Mactavous, L.; NIHR BioResource; Lyons, P.A.; Doffinger, R.; Bradley, J.R.; Smith, K.G.C.; et al. Spontaneous, persistent, T cell-dependent IFN-γ release in patients who progress to Long COVID. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi9379. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, F.; Palmeira, J.D.F.; Oliveira, J.D.S.; Argañaraz, G.A.; Soares, C.R.J.; Nóbrega, O.T.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Argañaraz, E.R. Unraveling the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein long-term effect on neuro-PASC. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1481963. [CrossRef]

- Swank, Z.; Borberg, E.; Chen, Y.; Senussi, Y.; Chalise, S.; Manickas-Hill, Z.; Yu, X.G.; Li, J.Z.; Alter, G.; Henrich, T.J.; et al. Measurement of circulating viral antigens post-SARS-CoV-2 infection in a multicohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1599–1605. [CrossRef]

- Gultom, M.; Lin, L.; Brandt, C.B.; Milusev, A.; Despont, A.; Shaw, J.; Döring, Y.; Luo, Y.; Rieben, R. Sustained vascular inflammatory effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on human endothelial cells. Inflammation 2024, online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, E.A.; Amarilla, A.A.; Modhiran, N.; Parker, S.; Li, X.X.; Wijesundara, D.K.; Aguado, J.; Zamora, A.P.; McMillan, C.L.D.; Liang, B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 drives NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human microglia through spike protein. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2878–2893. [CrossRef]

- Cervia-Hasler, C.; Brüningk, S.C.; Hoch, T.; Fan, B.; Muzio, G.; Thompson, R.C.; Ceglarek, L.; Meledin, R.; Westermann, P.; Emmenegger, M.; et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long COVID. Science 2024, 383, eadg7942. [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.K.S.; Beydoun, H.A.; Von Ah, D.; Shadyab, A.H.; Wong, S.C.; Freiberg, M.; Ikramuddin, F.; Nguyen, P.K.; Gradidge, P.J.; Qi, L.; et al. Pre-pandemic leukocyte count is associated with severity of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection among older women in the Women's Health Initiative. Menopause 2025, 32, 197–206. [CrossRef]

- Girón Pérez, D.A.; Fonseca-Agüero, A.; Toledo-Ibarra, G.A.; Gomez-Valdivia, J.J.; Díaz-Resendiz, K.J.G.; Benitez-Trinidad, A.B.; Razura-Carmona, F.F.; Navidad-Murrieta, M.S.; Covantes-Rosales, C.E.; Giron-Pérez, M.I. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in outpatients and its association with viral load. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15145. [CrossRef]

- Swank, Z.; Senussi, Y.; Manickas-Hill, Z.; Yu, X.G.; Li, J.Z.; Alter, G.; Walt, D.R. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike is associated with post-acute Coronavirus Disease 2019 sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e487–e490. [CrossRef]

- Palestra, F.; Poto, R.; Ciardi, R.; Opromolla, G.; Secondo, A.; Tedeschi, V.; Ferrara, A.L.; Di Crescenzo, R.M.; Galdiero, M.R.; Cristinziano, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein activates human lung macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3036. [CrossRef]

- Yang, O.O. The immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Overview of lessons learned in the first 5 years. J. Immun. 2025, vkaf033. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jia, M.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, B.; Cui, D.; Feng, L.; Yang, W. One-year temporal changes in long COVID prevalence and characteristics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health 2023, 26, 934–942. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.H.; Zhang, S.; Porritt, R.A.; Noval Rivas, M.; Paschold, L.; Willscher, E.; Binder, M.; Arditi, M.; Bahar, I. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25254–25262. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.K.; Francisco, E.B.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Hall, E.; Herrera, M.; Parikh, P.; Cabrera-Mora, M.; et al. Immune-based prediction of COVID-19 severity and chronicity decoded using machine learning. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 700782. [CrossRef]

- Rhea, E.M.; Logsdon, A.F.; Hansen, K.M.; Williams, L.M.; Reed, M.J.; Baumann, K.K.; Holden, S.J.; Raber, J.; Banks, W.A. The S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood–brain barrier in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 368–378. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Venter, C.; Laubscher, G.J.; Lourens, P.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 172. [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, D.M.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Huang, H.H.; Beckmann, N.D.; Nirenberg, S.; Wang, B.; Lavin, Y.; Swartz, T.H.; Madduri, D.; Stock, A.; et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1636–1643. [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Darley, D.R.; Wilson, D.B.; Howe, A.; Munier, C.M.L.; Patel, S.K.; Juno, J.A.; Burrell, L.M.; Kent, S.J.; Dore, G.J.; et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 210–216. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Gouveia, M.I.M.; Marcelino, B.D.R.; Santos, C.S.D.; Lima, K.V.B.; Lima, L.N.G.C. Hyperinflammatory response in COVID-19: A systematic review. Viruses 2023, 15, 553. [CrossRef]

- Bocquet-Garçon, A. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on the innate immune system: A review. Cureus 2024, 16, e57008. [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, C.; Terpos, E.; Rosati, M.; Angel, M.; Bear, J.; Stellas, D.; Karaliota, S.; Apostolakou, F.; Bagratuni, T.; Patseas, D.; et al. Systemic IL-15, IFN-γ, and IP-10/CXCL10 signature associated with effective immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine recipients. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109504. [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S. COVID-19: The role of excessive cytokine release and potential ACE2 down-regulation in promoting hypercoagulable state associated with severe illness. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 313–329. [CrossRef]

- Kappelmann, N.; Dantzer, R.; Khandaker, G.M. Interleukin-6 as potential mediator of long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms of COVID-19. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 131, 105295. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.A.F.; Neves, P.F.M.D.; Lima, S.S.; Lopes, J.D.C.; Torres, M.K.D.S.; Vallinoto, I.M.V.C.; et al. Cytokine profiles associated with acute COVID-19 and Long COVID-19 syndrome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 922422. [CrossRef]

- Brodin, P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Capistrano, K.; Hussein, H.; Hafedi, A.; Shukla, D.; Naqvi, A. Oral SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk for Long COVID. Rev. Med. Virol. 2025, 35, e70029. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.T.; Khan, H.; Khalid, A.; Mahmood, S.F.; Nasir, N.; Khanum, I.; de Siqueira, I.; Van Voorhis, W. Chronic inflammation in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 modulates gut microbiome: A review of literature on COVID-19 sequelae and gut dysbiosis. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 22. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M.; Fumoso, F.; Conti, M.; Becchetti, A.; Bozzi S, Mencarini, T., et al. Low-grade inflammation in long COVID syndrome sustains a persistent platelet activation associated with lung impairment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic. 2025, 10, 20–39. [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.E.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [CrossRef]

- Terry, P.; Heidel, R.E.; Wilson, A.Q.; Dhand, R. Risk of long COVID in patients with pre-existing chronic respiratory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2025, 12, e002528. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D.G.; Ng, R.H.; Wang, K.; Choi, J.; Li, S.; Hong, S.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022, 185, 881–895.e20. [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Living with COVID-19: Second Review. NIHR Themed Review 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3310/themedreview_45225 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Bartsch, S.M.; Chin, K.L.; Strych, U.; John, D.C.; Shah, T.D.; Bottazzi, M.E.; O’Shea, K.J.; Robertson, M.; Weatherwax, C.; Heneghan, J.; et al. The current and future burden of Long COVID in the United States (US). J. Infect. Dis. 2025, jiaf030. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Knight, M.; A’Court, C.; Buxton, M.; Husain, L. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020, 370, m3026. [CrossRef]

- Raharinirina, N.A.; Gubela, N.; Börnigen, D.; Smith, M.R.; Oh, D.Y.; Budt, M.; Mache, C.; Schillings, C.; Fuchs, S.,; Dürrwald, R.; Wolff, T.; Hölzer, M.; Paraskevopoulou, S.; von Kleist, M. SARS-CoV-2 evolution on a dynamic immune landscape. Nature 2025, 639, 196–204. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M. The costs of Long COVID. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e213140. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).