Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Procedure

4.3. Data Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 2 Virus |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1α |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-1Ra | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-2Rα | Interleukin 2 receptor alpha |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-7 | Interleukin-7 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-9 | Interleukin-9 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| IL-15 | Interleukin-15 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| IL-31 | Interleukin-31 |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-6R | IL-6 receptor |

| IP-10/CXCL10 | Inducible protein-10 |

| MCP-1/MCAF/CCL2 | Monocyte chemoattractant pro-tein-1 |

| MIP-1α/CCL3 | Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha |

| MIP-1β/CCL4 | Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta |

| CCL7 | Chemokine ligand 7 |

| CCL8 | Chemokine ligand 8 |

| CCL9 | Chemokine ligand 9 |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrom |

| F | Female |

| M | Male |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| TH17 | T helper 17 cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte colony stimulating factor |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony stimulating factor |

| GM-CS | Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor |

| ICAM | Intercellular adhesion molecules |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-derived growth factor-BB |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, T.; Xia, J.; Wei, Y.; Wu, W.; Xie, X.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, H.; Guo, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, G.; Jiang, R.; Gao, Z.; Jin, Q.; Wang, J.; Cao, B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, L.J.; Bellamy, R.; Garner, P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. Available online: https://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected (accessed on day month year).

- Chousterman, B.G.; Swirski, F.K.; Weber, G.F. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, Z.Q. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Perlman, S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Liang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. medRxiv 2020, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, G.; Tamburello, A.; Castelnovo, L.; Laria, A.; Mumoli, N.; Faggioli, P.M.; Stefani, I.; Mazzone, A. Immunotherapy of COVID-19: inside and beyond IL-6 signalling. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zizzo, G.; Cohen, P.L. Imperfect storm: is interleukin-33 the Achilles heel of COVID-19? Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buszko, M.; Nita-Lazar, A.; Park, J.H.; Schwartzberg, P.L.; Verthelyi, D.; Young, H.A.; et al. Lessons learned: new insights on the role of cytokines in COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Guan, X.; Xiang, Y. Can we use interleukin-6 (IL-6) blockade for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-induced cytokine release syndrome (CRS)? J. Autoimmun. 2020, 111, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 842–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, B.; Qu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, J.; Feng, Y.; et al. Detectable serum severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral load (RNAemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 level in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Qu, M.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, K.; Lai, C.; Tang, Q.; et al. The timeline and risk factors of clinical progression of COVID-19 in Shenzhen, China. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Cruz, A.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Oliveira, A.I.; Dias, L.; Matos, A.R.; Carvalho, A.; et al. Interleukin-6 is a biomarker for the development of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 613422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovijn, J.; Lindgren, C.M.; Holmes, M.V. Genetic variants mimicking therapeutic inhibition of IL-6 receptor signaling and risk of COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. The two-faced cytokine IL-6 in host defense and diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Fu, B.; Zheng, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, C.; Qi, Y.; et al. Pathogenic T cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storm in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzone, A.; Castelnovo, L.; Tamburello, A.; Gatti, A.; Brando, B.; Faggioli, P.; et al. Monocytes could be a bridge from inflammation to thrombosis on COVID-19 injury: a case report. Thromb. Update 2020, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, A.; Salvati, L.; Maggi, L.; Capone, M.; Vanni, A.; Spinicci, M.; Mencarini, J.; Caporale, R.; Peruzzi, B.; Antonelli, A.; Trotta, M.; Zammarchi, L.; Ciani, L.; Gori, L.; Lazzeri, C.; Matucci, A.; Vultaggio, A.; Rossi, O.; Almerigogna, F.; Parronchi, P.; Fontanari, P.; Lavorini, F.; Peris, A.; Rossolini, G.M.; Bartoloni, A.; Romagnani, S.; Liotta, F.; Annunziato, F.; Cosmi, L. Impaired immune cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19 is IL-6 dependent. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 4694–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaescusa, L.; Zaragozá, F.; Gayo-Abeleira, I.; Zaragozá, C. A new approach to the management of COVID-19. Antagonists of IL-6: siltuximab. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 1126–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Potere, N.; Batticciotto, A.; Alessandra, —.; Porreca, E.; Cappelli, A.; Abbate, A.; Dentali, F.; Bonaventura, A. The role of IL-6 and IL-6 blockade in COVID-19. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 601–618.

- Gao, Y.D.; Ding, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, J.J.; Kursat Azkur, A.; Azkur, D.; et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: a review. Allergy 2021, 76, 428–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, T.L.; Murray, B.P.; Hagan, R.S.; Mock, J.R. COVID-19: Clean up on IL-6. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 63, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Ling, Y.; Lu, G.; Liu, F.; Yi, Z.; et al. Viral and host factors related to the clinical outcome of COVID-19. Nature 2020, 583, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, T.T.; Montón, C.; Torres, A.; Cabello, H.; Fillela, X.; Maldonado, A.; et al. Comparison of systemic cytokine levels in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, severe pneumonia, and controls. Thorax 2000, 55, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Matthay, M.A.; Calfee, C.S. Is a “cytokine storm” relevant to COVID-19? JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, Online ahead of print, 30 June.

- Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Verdugo-Rodriguez, A.; Rodriguez, L.L.; Borca, M.V. The role of interleukin 6 during viral infections. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmig, L.M.; Wu, D.; Gold, M.; Pettit, N.N.; Pitrak, D.; Mueller, J.; et al. IL6 inhibition in critically ill COVID-19 patients is associated with increased secondary infections. medRxiv 2020, Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Somers, E.C.; Eschenauer, G.A.; Troost, J.P.; Golob, J.L.; Gandhi, T.N.; Wang, L.; et al. Tocilizumab for treatment of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrey, A.C.; Qeadan, F.; Middleton, E.A.; Pinchuk, I.V.; Campbell, R.A.; Beswick, E.J. Cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19: Innate immune, vascular, and platelet pathogenic factors differ in severity of disease and sex. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wei, J.; Huang, F.; et al. Plasma IP-10 and MCP-3 levels are highly associated with disease severity and predict the progression of COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz de Paula, C.B.; de Azevedo, M.L.V.; Nagashima, S.; Camargo Martins, A.P.; Scaranello Malaquias, M.A.; Ribeiro dos Santos Miggiolaro, A.F.; et al. IL-4/IL-13 remodeling pathway of COVID-19 lung injury. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, A.N.; Sutherland, T.E.; Marie, C.; Preissner, S.; Bradley, B.T.; Carpenter, R.M.; et al. IL-13 is a driver of COVID-19 severity. JCI Insight 2021, 6, 150107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, G.B.; Burgess, S.L.; Sturek, J.M.; Donlan, A.N.; Petri, W.A.; Mann, B.J. Evaluation of K18-hACE2 Mice as a Model of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Z.; Ji, J.; Wen, C. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: The Current Evidence and Treatment Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lan, Z.; Ye, J.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Qin, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, P. Cytokine Storm: The Primary Determinant for the Pathophysiological Evolution of COVID-19 Deterioration. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 589095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsinprasert, W.; Jittikoon, J.; Sangroongruangsri, S.; Chaikledkaew, U. Circulating Levels of Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-10, But Not Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha, as Potential Biomarkers of Severity and Mortality for COVID-19: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 41, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.Y.; Zulkafli, N.E.S.; Ad’hiah, A.H. Serum Profiles of Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Non-Hospitalized Patients with Mild/Moderate COVID-19 Infection. Immunol. Lett. 2023, 260, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Tan, C.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Shen, G.; Zhu, P.; Yang, G.; Xie, X. Changes of Serum IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, TNF-α, IP-10 and IL-4 in COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, J.; Lara-Reyna, S.; Jarosz-Griffiths, H.; McDermott, M.F. Tumour Necrosis Factor Signalling in Health and Disease. F1000Research 2019, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, Z.M.; Kalyanasundram, J.; Zain, R.M.; Thayan, R.; Basri, D.F.; Yap, W.B. Prospective Roles of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-α) in COVID-19: Prognosis, Therapeutic and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Tabarsi, P.; Jamaati, H.; Roofchayee, N.D.; Dezfuli, N.K.; Hashemian, S.M.; Moniri, A.; Marjani, M.; Malekmohammad, M.; Mansouri, D.; et al. Increased Serum Levels of Soluble TNF-α Receptor Is Associated with ICU Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 592727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leija-Martínez, J.J.; Huang, F.; Del-Río-Navarro, B.E.; Sanchéz-Muñoz, F.; Muñoz-Hernández, O.; Giacoman-Martínez, A.; Hall-Mondragon, M.S.; Espinosa-Velazquez, D. IL-17A and TNF-α as Potential Biomarkers for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Mortality in Patients with Obesity and COVID-19. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.A.; Zenkova, M.A.; Sen’kova, A.V. Pulmonary Fibrosis as a Result of Acute Lung Inflammation: Molecular Mechanisms, Relevant In Vivo Models, Prognostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.-B.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Ma, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-P.; Liu, W.-Y.; George, J.; et al. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Greater Severity of COVID-19 in Patients with Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Metabolism 2020, 108, 154244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelová, H.; Hošek, J. TNF-α Signalling and Inflammation: Interactions between Old Acquaintances. Inflamm. Res. 2013, 62, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultheiß, C.; Willscher, E.; Paschold, L.; Gottschick, C.; Klee, B.; Henkes, S.-S.; Bosurgi, L.; Dutzmann, J.; Sedding, D.; Frese, T.; et al. The IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF Cytokine Triad Is Associated with Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhang, W.; Wu, T.; Wen, T.; Liu, J.; Guo, X.; Huang, C.; Jiao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, B.; Cui, L. Serum Cytokine and Chemokine Profile in Relation to the Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, ciaa248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszko, M.; Park, J.-H.; Verthelyi, D.; Sen, R.; Young, H.A.; Rosenberg, A.S. The dynamic changes in cytokine responses in COVID-19: a snapshot of the current state of knowledge. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, B.A.; Elemam, N.M.; Maghazachi, A.A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors during COVID-19 infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Jiang, A.; et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.S.; Shu, T.; Kang, L.; Wu, D.; Zhou, X.; et al. Temporal profiling of plasma cytokines, chemokines and growth factors from mild, severe and fatal COVID-19 patients. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

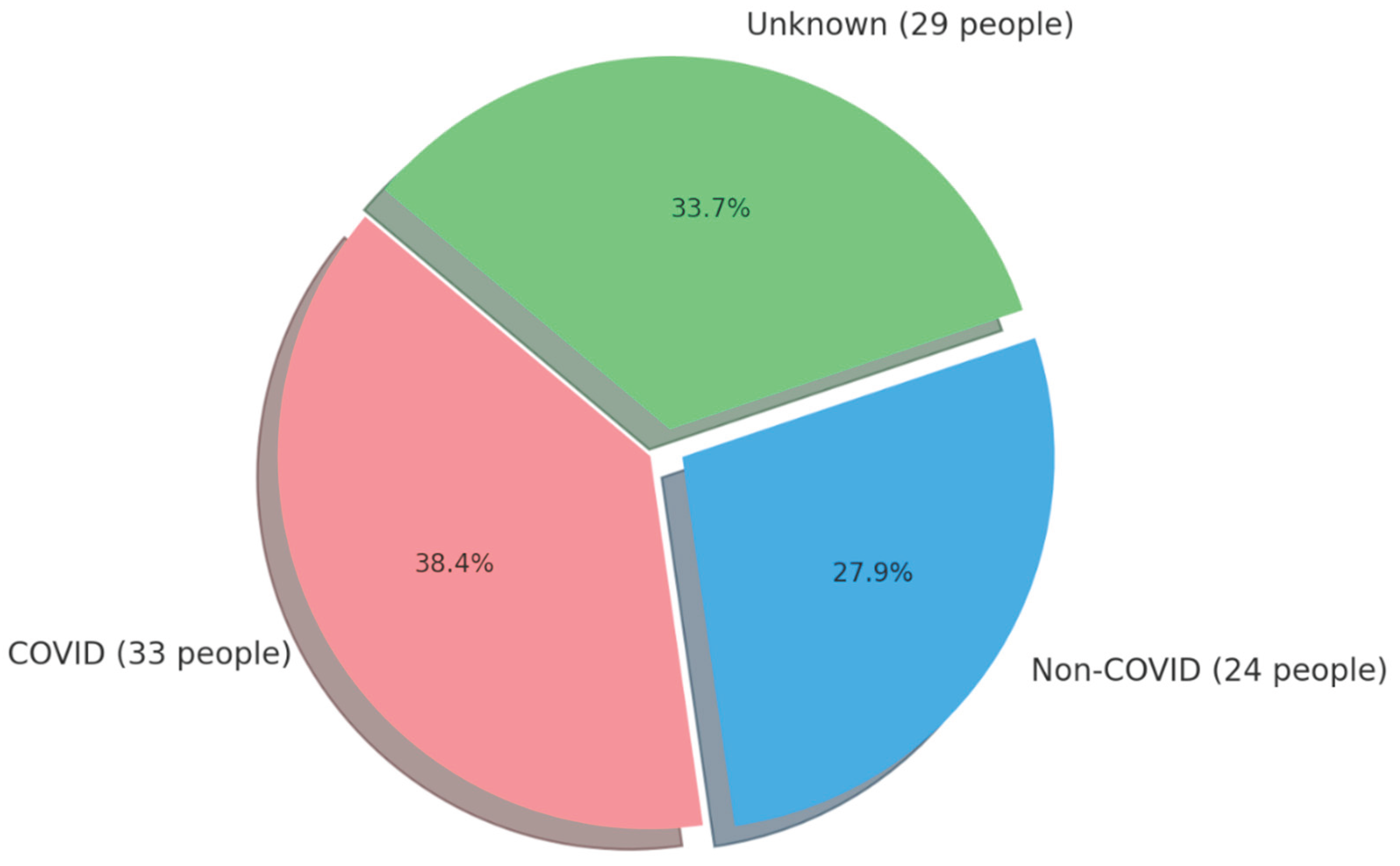

| Variable | NON–COVID GROUP (n=24) | COVID GROUP (n=33) | p-Value | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | ||

| Age [years] | 52.21 | 9.38 | 48.5 | 41.0 | 75.0 | 50.97 | 9.83 | 49.0 | 35.0 | 86.0 | 0.6247* |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 26.85 | 4.99 | 26.03 | 21.19 | 39.84 | 26.31 | 3.63 | 26.09 | 19.94 | 34.09 | 0.9170* |

| Waist circumference [cm] | 91.45 | 10.49 | 94.0 | 76.0 | 111.0 | 90.77 | 10.06 | 92.0 | 71.0 | 107.0 | 0.9428* |

| Gender n (%) |

F = 13 (45.8) M = 11 (54.2) |

F = 15 (45.5) M = 18 (55.5) |

0.5160** | ||||||||

| Smoking n (%) |

NO = 19 (79.2) YES = 5 (20.8) |

NO = 30 (90.9) YES = 3 (9.1) |

0.2076** | ||||||||

| Alcohol consumption n (%) |

YES = 6 (25.0) NO = 18 (75.0) |

YES = 5 (15.1) NO = 28 (84.9) |

0.3523** | ||||||||

| Physical activity n (%) |

Low = 4 (16.7) Moderate =14 (58.3) High = 6 (25.0) |

Low = 8 (24.2) Moderate = 22 (66.7) High = 3 (9.1) |

0.2536** | ||||||||

| Variable | NON–COVID GROUP (n=24) | COVID GROUP (n=33) | p-Value | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | ||

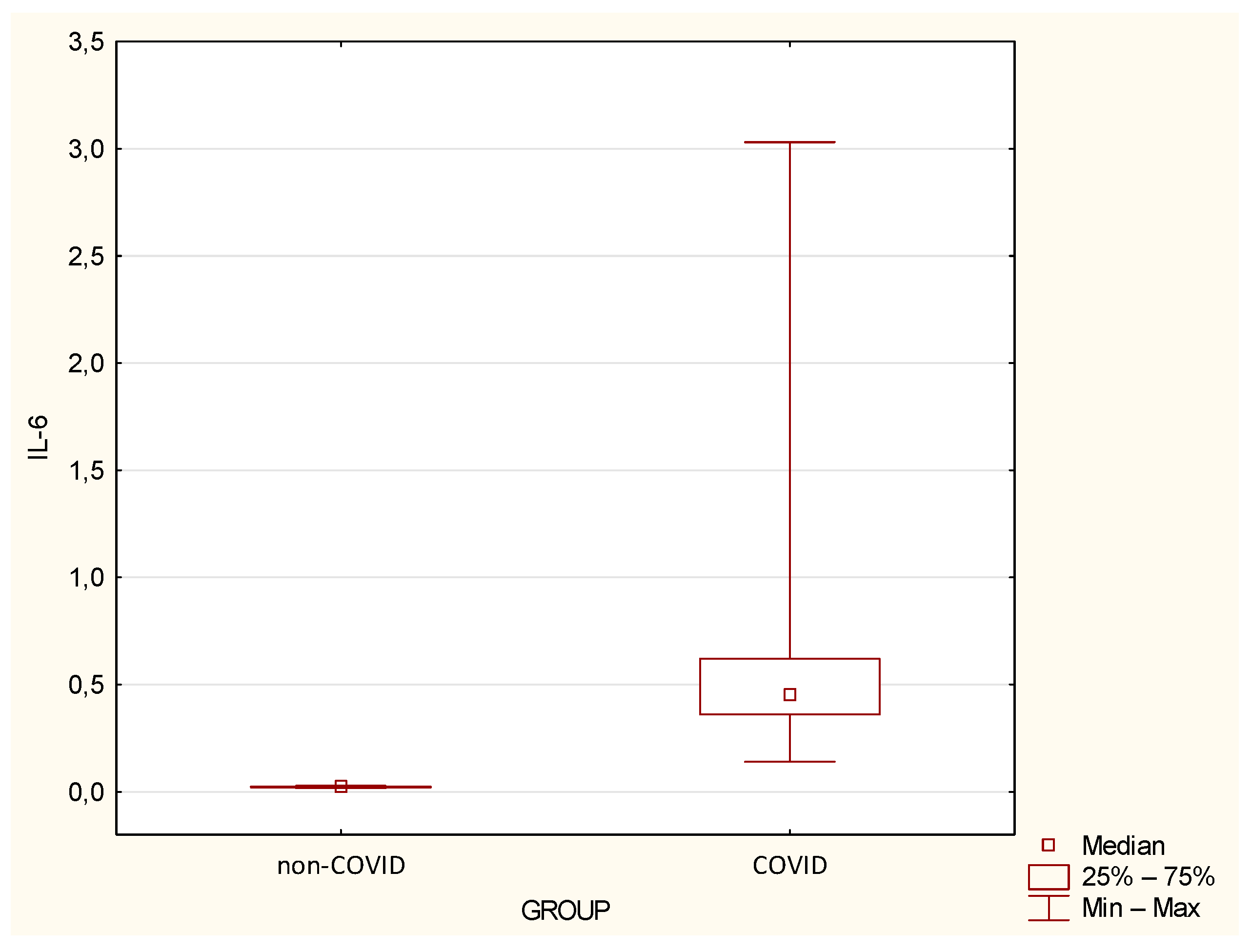

| IL-6 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 3.03 | <0.0001 |

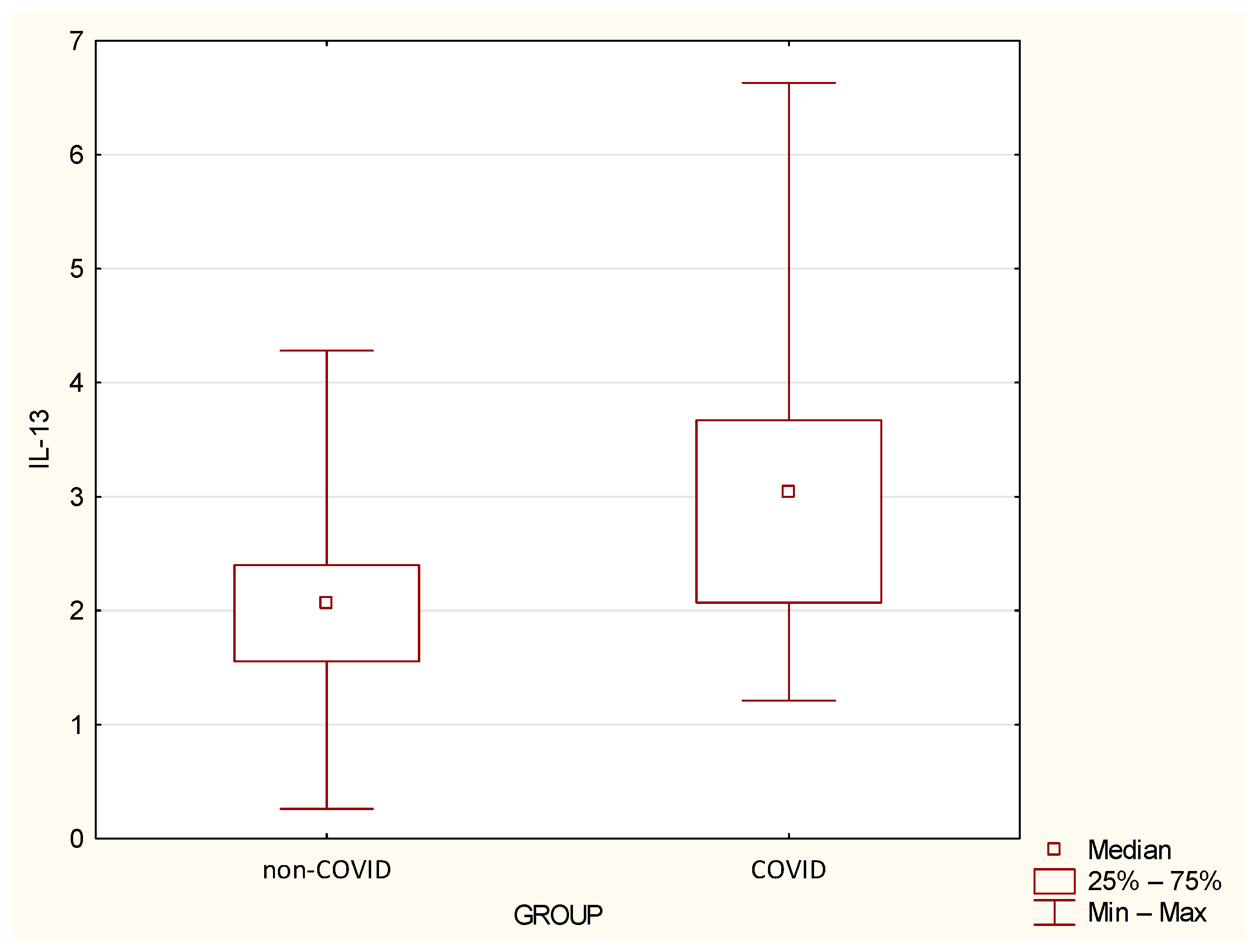

| IL-13 | 2.1 | 0.97 | 2.07 | 0.26 | 4.28 | 3.25 | 1.49 | 3.04 | 1.21 | 6.63 | 0.0016 |

| Variable | NON–COVID GROUP (n=24) | COVID GROUP (n=33) | p-Value | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | ||

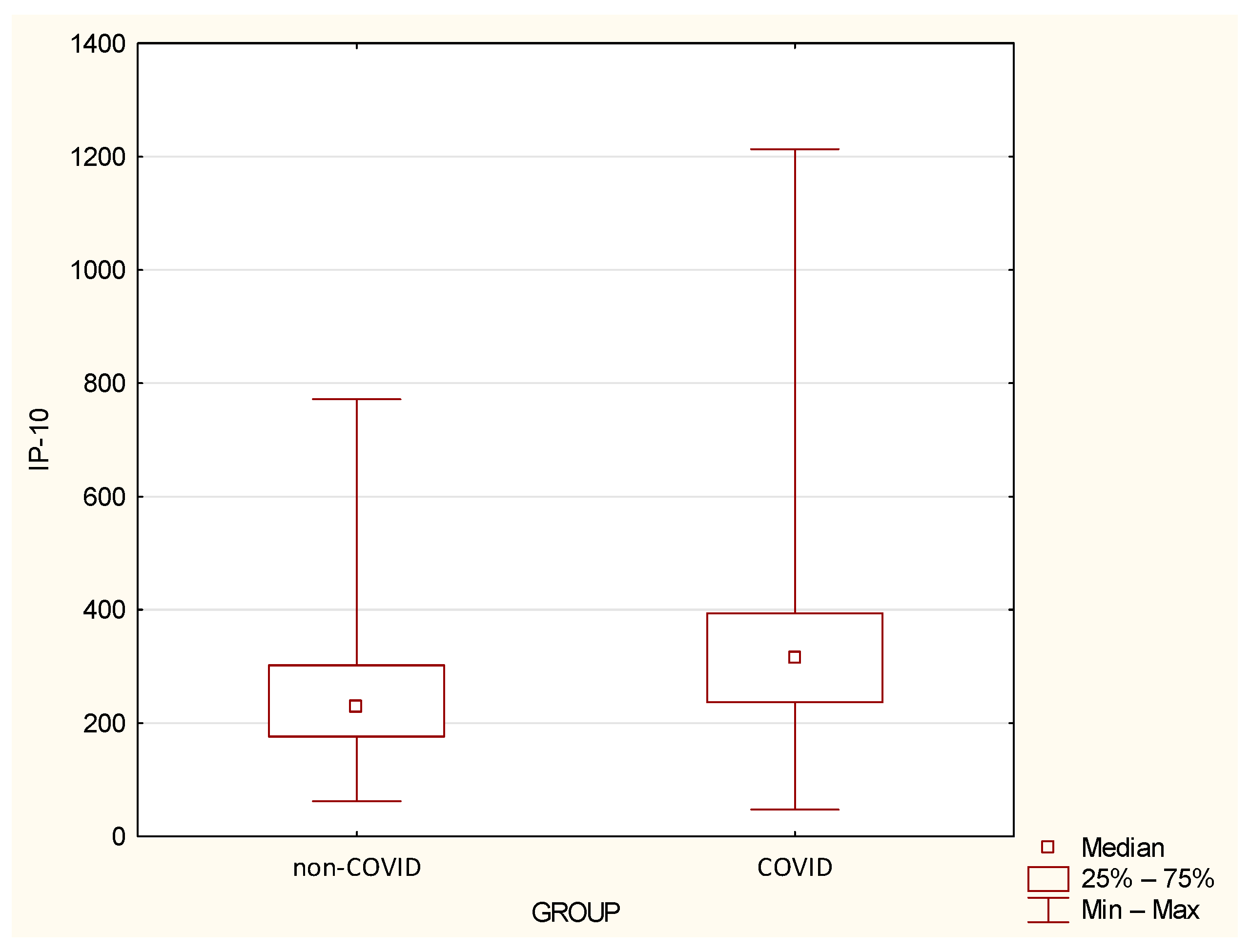

| IP-10 | 260.88 | 145.33 | 228.81 | 62.22 | 771.66 | 335.46 | 203.53 | 316.22 | 47.47 | 1213.3 | 0.0419 |

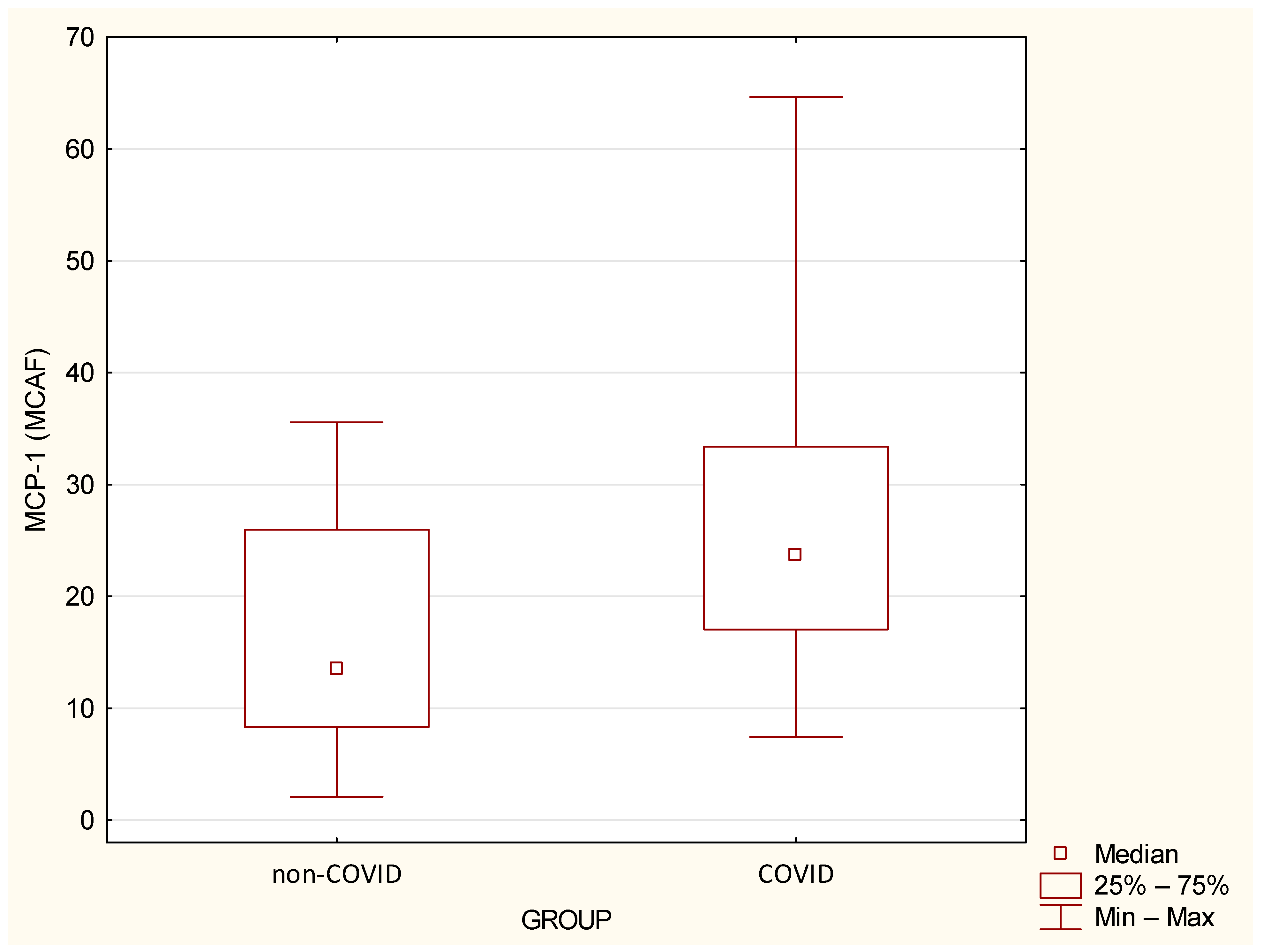

| MCP-1 (MCAF) | 16.67 | 10.39 | 13.53 | 2.09 | 35.57 | 27.53 | 14.17 | 23.74 | 7.45 | 64.65 | 0.0024 |

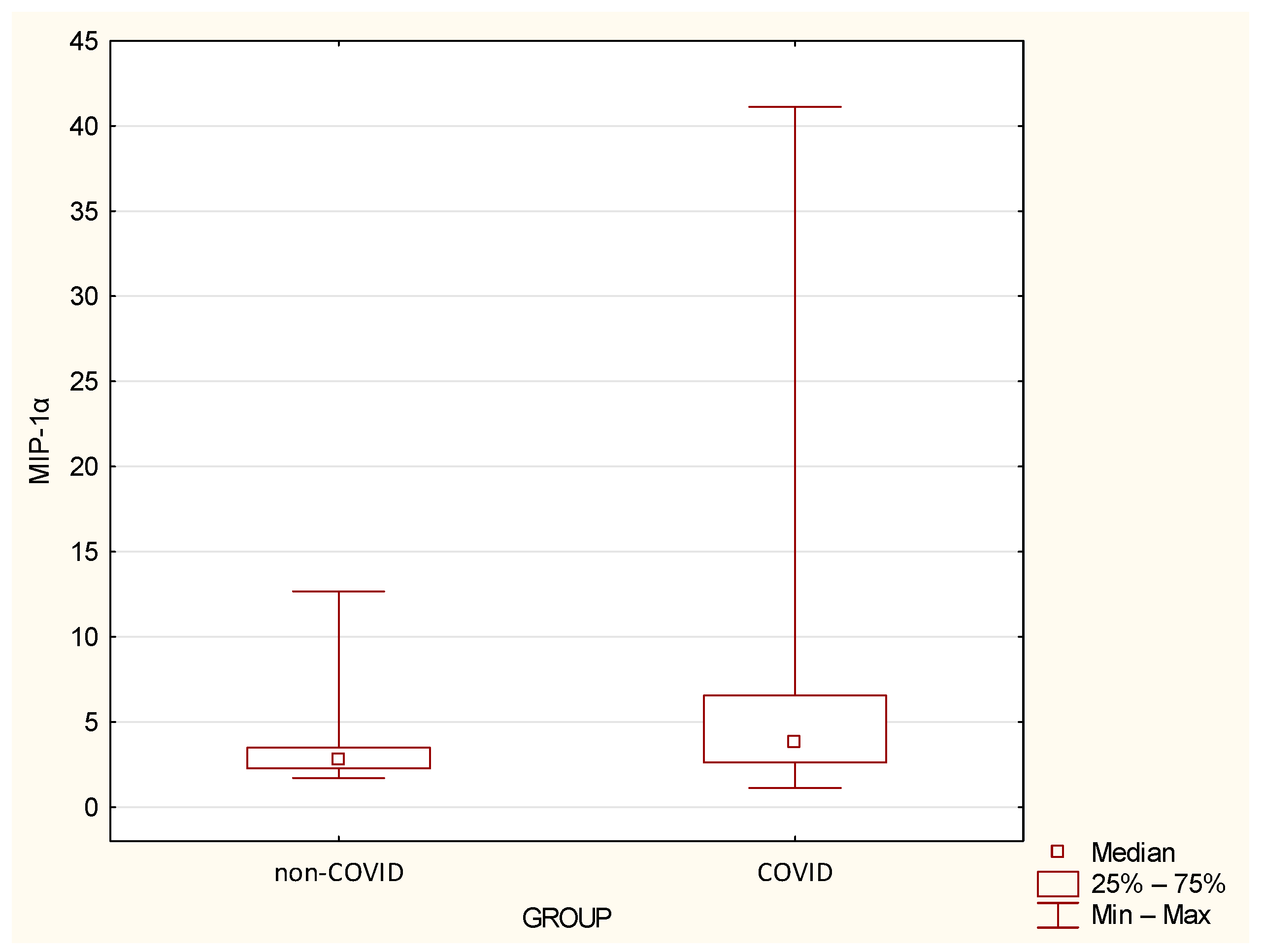

| MIP-1α | 3.49 | 2.42 | 2.75 | 1.71 | 12.67 | 6.77 | 8.04 | 3.85 | 1.13 | 41.11 | 0.0155 |

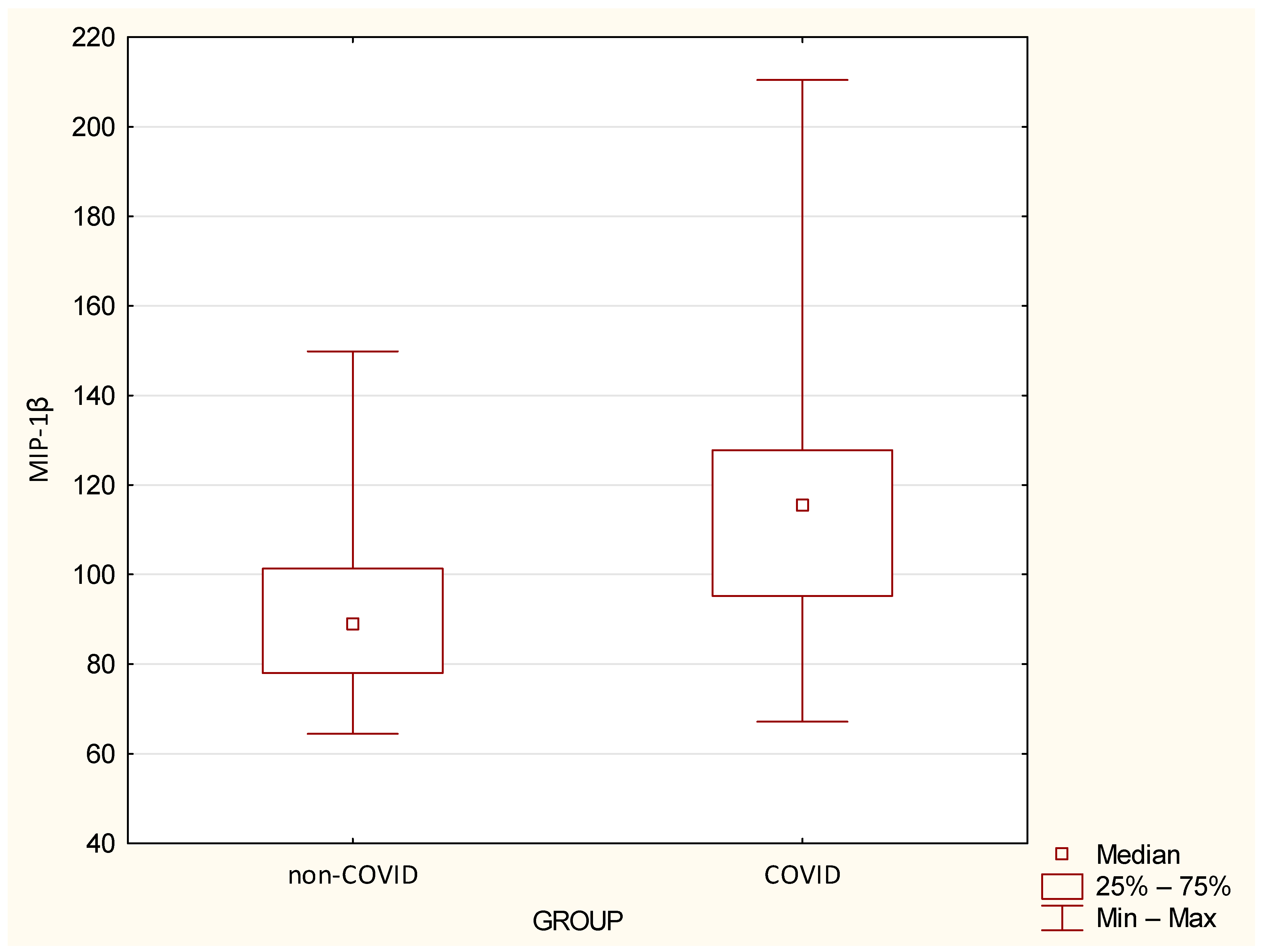

| MIP-1β | 92.28 | 21.21 | 88.71 | 64.5 | 149.84 | 118.03 | 34.08 | 115.21 | 67.17 | 210.45 | 0.0007 |

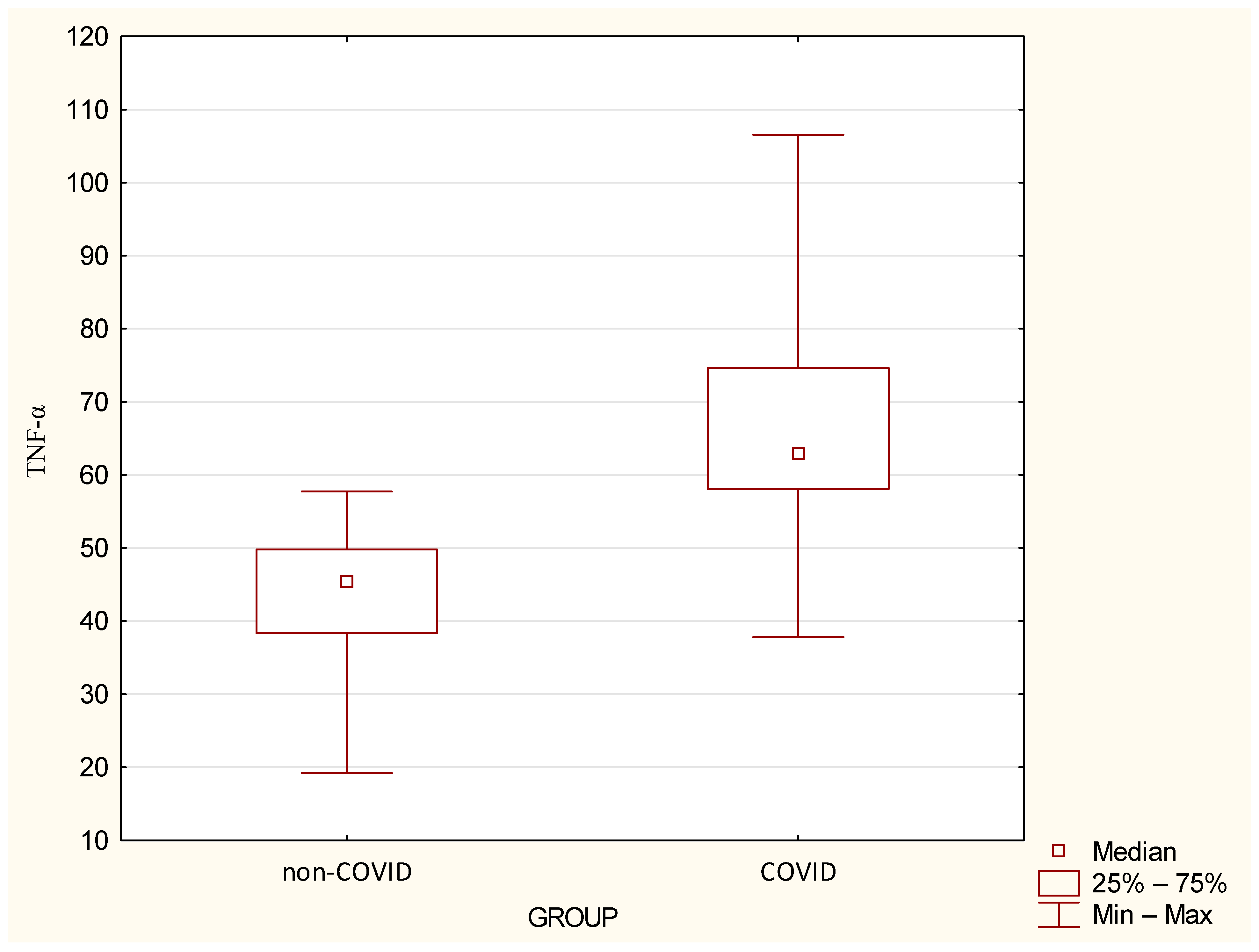

| TNF-α | 43.52 | 10.89 | 45.37 | 19.19 | 57.71 | 66.05 | 15.13 | 62.86 | 37.79 | 106.56 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).