1. Introduction

Intestinal parasitosis caused by helminths is one of the main health problems affecting goat and sheep production [

1]. This disease involves the greatest expense in production systems, its infections lead to losses in milk production, meat, reproduction and even mortality [

2]. This disease is multietiological in animals, since a complexity of genera and species of helminths can be found in an organism and these increase the susceptibility of the host to other opportunistic diseases [

3].

The sharing of grazing areas predisposes small ruminants to infection with strongylids such as:

Oesophagostomum venolosum,

Chabertia ovina (superfamily Strongyloidea),

Nematodirus battus,

Cooperia curticei,

Trichostrongylus axei,

Trichostrongylus columbriformis and

Haemonchus contortus (superfamily Trichostrongyloidea) [

4].

The gastrointestinal nematodes that affect sheep and goats are the same, but the one of greatest concern is

Haemonchus contortus, because it is hematophagous and highly prolific, so in flocks there are usually massive infections, also goats are more susceptible to this species [

5].

Currently, the treatment of endoparasitosis with chemical control is compromised by the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains, which forces us to look for control alternatives, in which local knowledge focused on medicinal plants is gaining importance [

6].

The inadequate use of conventional anthelmintics, in dosages, continuous application and greater frequency of the same active ingredient, has generated the problem of multiple resistance [

7,

8], also the accumulation of residues in products such as milk and meat, as well as damage to the environment [

9]. In view of these problems, there is a need to develop alternative methods to treat intestinal helminth parasitosis, such as the use of plants used in traditional medicine, with secondary metabolites, which has become of international interest [

10,

11].

Plants contain a range of bioactive compounds to deal with various pathogens, these can act as fungicides, bactericides, antivirals and antiparasitics, these properties can lead to the development of new treatments. The groups of bioactive compounds that have gained relevance include terpenes, flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, resins and their compounds [

12,

13].

The in vitro evaluation of anthelmintic plants allows confirming ovicidal and larvicidal activity, with the use of leaves, fruits, stems, roots and seeds, and the results are fast and economical [

14]. The objective of the present work was to evaluate the larvicidal effect of ethanolic extract of

Piper auritum and

Capsicum annuum (tree chili) with gastrointestinal nematodes of goats under in vitro conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

The experiments were carried out in the Biochemistry and cell biology laboratory of the Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia of the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, located in Ex-Hacienda 5 Señores, Oaxaca, Mexico, between the coordinates 17°02′53″N 96°42′44″O and at 1,555 and 1,557 masl.

2.2. Plant Material

Piper auritum leaves and fruits of

Capsicum annuum were collected in May 2025 in San Cristóbal Amatlán, Oaxaca, located between parallels 16°12′ and 16°24′ north latitude; meridians 96°18′ and 96°28′ west longitude, altitude between 1,300 and 3,200 masl [

15]. Leaves of plants close to flowering and ripe fruits were selected, washed with distilled water and dried in an oven at 42±1 °C. Subsequently, they were ground to obtain particles of approximately 1 mm.

2.3. Extract Preparation

500 g of each powder was extracted in 1,000 ml of 75 % ethanol for 72 h at room temperature [

16]. Chlorophylls and impurities were removed by filtration using activated carbon and filter paper. Solvent removal was performed using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to obtain crude extracts [

17,

18]. The yield of the extracts (%) was calculated with the following formula (1).

2.4. Chromatographic Profile

The compounds were separated on a column packed with silica gel containing 3.5 g of crude extract in a 1:30 ratio. Three different systems were used to obtain fractions: 1) 1:9 hexane/dichloromethane elution; 2) pure dichloromethane; and 3) 1:1 ethyl acetate/hexane, each yielding 12 fractions of 20 ml. The fractions were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography. The compounds were developed with white light, ultraviolet light at λ = 365 nm, and 2 % cerium sulfate solution [

19].

2.5. Culture and Isolation of L3 Larvae

Feces were collected from the rectum of naturally infested goats, those with a high parasite load (>700 eggs per gram of feces) were considered. Stool cultures were prepared with approximately 30 g of feces pooled in glass jars, moistened, and incubated at 28±1°C for 15 days. Temperature, humidity, and ventilation were monitored daily. Larvae were recovered using the Baermann technique [

20].

2.6. Identification of the Nematodes Used

From the L3 larvae obtained in the stool cultures, 25 mg per sample was used, and genomic DNA was extracted using the “Quick-DNA MiniPrep” kit (Zymo Research, USA) following the supplier’s instructions. Amplification and determination of the genera present in the samples was performed by PCR using 200 ng of DNA and oligonucleotides specific for Haemonchus spp. (ITS2GF 5’-CAC GAA TTG CAG ACG CTT AG and ITS2GR 5’-GCT AAA TGA TAT GCT TAA GTT CAG C), Trichostrongylus spp. (sp6C 5’-GAT TTA GGT GAC ACT ATA G and t7ch 5’-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG G) and Oesophagostomum spp. (oeso5 5’-TCG ACT AGC TTC AGC GAT G and oeso3 5’-CCA AAG CAT TCT TAG TCG CT). The conditions of each reaction were: 95 ºC/3’ initial denaturation; followed by 35 cycles, 95 ºC/20”, 55 ºC/20” and 72 ºC/40” each; a final extension of 72 ºC/5′ in an AB Applied Biosystem thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Spain). The amplified products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel to corroborate the size of each product.

2.7. Bioassays

Extracts of Piper auritum and Capsicum annuum were used as treatments at concentrations of 100, 350, 1000, and 3500 µg mL-1, with three replicates. Albendazole 2 mg mL-1 was used as a positive control and distilled water as absolute control.

A total of 43 ± 11 L3 suspended in 100 µl of distilled water was added, and 100 µl of extract was added. These were placed in 12-well cell culture plates, each well representing an experimental unit. The larvae were stored at 28±1°C for 36 hours. Treatments were inspected every eight hours under a stereoscopic microscope. Larvae that were coiled or rigid and motionless were considered dead [

21]. The percentage of larval mortality (LM) was calculated with the formula 2:

2.8. Data Analysis

Since the data followed a normal distribution, the comparison of treatment means by time was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test, with a significance level of α = 0.05. Probit analysis was used to estimate the mean concentration (LC50) and lethal dose (LC90) with the SPSS statistical package for Windows.

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Bioactive Compounds of the Extracts

The yield of the extracts in dry mass was determined to be 2.23 % for

Piper auritum and 2.61 % for

Capsicum annuum. The presence of flavonoids, coumarins, and alkaloids in

Piper auritum was revealed, as well as the availability of alkaloids, tannins, and coumarins in

Capsicum annuum according to the chromatographic patterns described by Torres-Rodriguez et al. [

22], are shown in the

Table 1.

3.2. Larvicidal Activity

Exposure of L3 caprine nematode larvae to ethanolic extracts of

Capsicum annuum and

Piper auritum at different concentrations for 32 hours showed larvicidal activity. A trend toward increased mortality was observed over time, compared to the negative control, which demonstrated natural larval survival (

Table 1).

Table 2.

Mortality of L3 larvae of goat nematodes exposed to extracts at different doses.

Table 2.

Mortality of L3 larvae of goat nematodes exposed to extracts at different doses.

| |

|

Mortality of L3 Larvae (%) |

| Treatment |

Concentration µg ml-1 |

0 hr |

8 h |

16 h |

24 h |

32 h |

| Capsicum annuum |

100 |

0 |

29.27±14.31cde

|

37.45±13.96cd

|

53.94±7.47cd

|

63.69±5.85bc

|

| 350 |

0 |

39.79±19.69bcd

|

53.33±11.28bc

|

56.30±11.02cd

|

67.45±7.08bc

|

| 1,000 |

0 |

43.83±13.46bcd

|

59.91±7.70bc

|

69.30±8.20bc

|

76.98±9.09abc

|

| 3,500 |

0 |

67.81±17.21b

|

78.52±12.80ab

|

89.32±4.02ab

|

93.82±2.75a

|

| Piper auritum |

100 |

0 |

5.95±7.00e

|

19.42±6.22de

|

28.89±10.11def

|

32.76±10.70d

|

| 350 |

0 |

5.32±2.75e

|

8.65±7.91e

|

23.98±27.16ef

|

34.03±16.10d

|

| 1,000 |

0 |

14.43±10.89de

|

25.27±6.39de

|

32.75±7.91de

|

59.69±17.75c

|

| 3,500 |

0 |

45.54±8.20bc

|

60.89±14.85abc

|

79.74±7.24abc

|

88.09±6.24ab

|

| Albendazole |

2,000 |

0 |

100±0.00a

|

100±0.00a

|

100±0.00a

|

100±0.00a

|

| Water |

00 |

0 |

5.32±4.45e

|

3.12±1.20e

|

4.16±1.71e

|

4.02±1.70e

|

| |

|

|

F= 27.94

Sig.= .000 |

F= 42.09

Sig.= .000 |

F= 30.89

Sig.= .000 |

F=20.42

Sig.= .000 |

With the Capsicum annuum extract at 100 µg mL-1, a 63.69 % mortality rate was achieved, with 350 µg ml-1 an effectiveness of 67.45% was observed, followed by the 1,000 µg mL-1 concentration achieving a 76.98 % reduction, with the 3,500 µg mL-1 dose being the best with 93.82 % effectiveness. Likewise, with the Piper auritum extract, after 32 hours of exposure to different concentrations of larvae, 100 µg mL-1 achieved 32.76% effectiveness, 350 µg mL-1 showed 34.03 % mortality, 1,000 µg mL-1 achieved 59.69 % mortality, and 3,500 µg mL-1 increased to 88.09 % effectiveness. The two extracts showed the same trend: higher concentrations and longer durations increased the larvicidal effect.

Likewise, lethal doses were estimated for 50 % and 90 % of larvae exposed to the evaluated extracts for 32 hours. These are shown in

Table 2.

Table 3.

Lethal doses of extracts against L3 larvae of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats.

Table 3.

Lethal doses of extracts against L3 larvae of gastrointestinal nematodes in goats.

| Extract |

LC50

µg ml-1

|

95 % confidence limits |

LC90

µg ml-1

|

95 % confidence limits |

Prediction equation |

R2

|

p |

| Lower |

Upper |

Lower |

Upper |

| Capsicum annuum |

47.16 |

5.37 |

113.31 |

3,703.09 |

1,593.48 |

29,182.84 |

y= -0.62+0.79x |

0.73 |

0.000 |

| Piper auritum |

457.49 |

216.49 |

875.89 |

7,780.48 |

2,837.40 |

110,579.69 |

y= -2.99+1.13x |

0.70 |

0.000 |

According to the Probit analysis, the LC50 of Capsicum annuum extract was 47.16 µg mL-1 and the LC90 was 3,703.09 µg mL-1, while the LC50 of Piper auritum was 457.49 µg mL-1 and LC90 was 7,780.48 µg mL-1, suggesting that Capsicum annuum has a greater anthelmintic effect than Piper auritum.

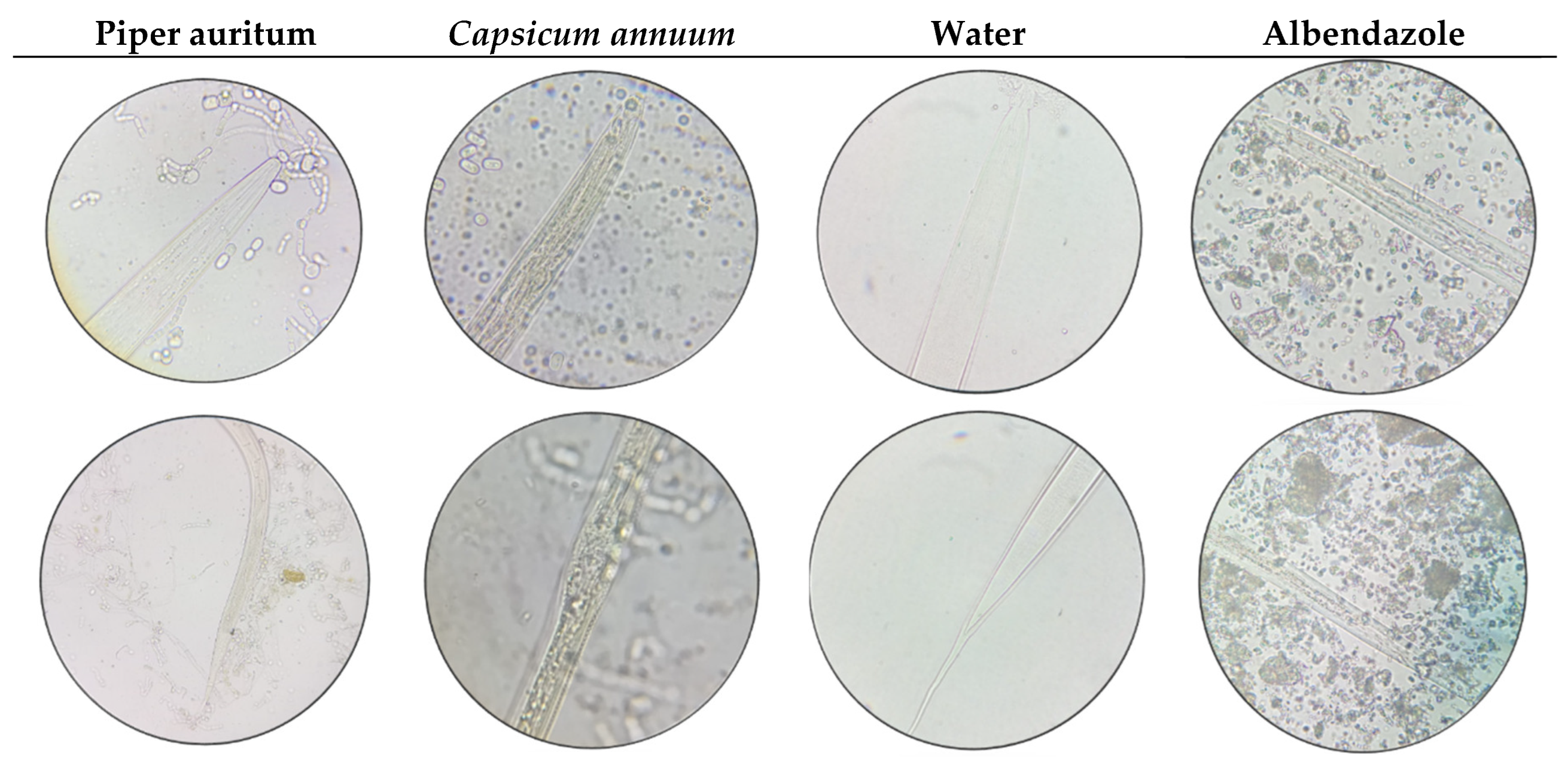

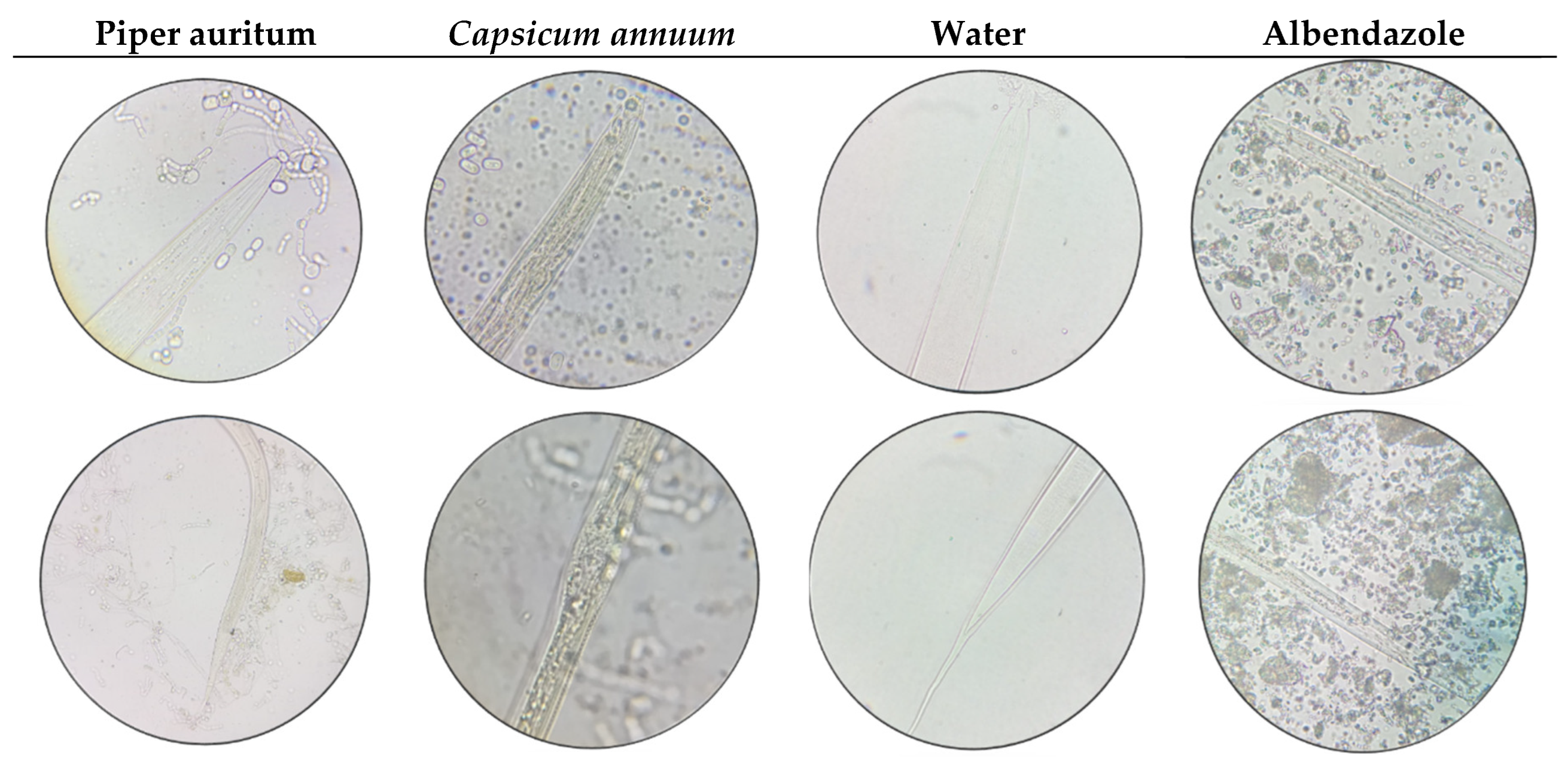

Figure 1.

Larvae exposed to Piper auritum and Capsicum annuum extracts, water and albendazole, after 32 hours. Morphological alterations were observed in the larvae exposed to the treatments. It has been demonstrated that exposure to Piper auritum results in the infiltration of the extract through the pod, accompanied by deformations in the cuticle. Furthermore, muscle deterioration was observed throughout the body and digestive tract. In the case of Capsicum annuum, the transfer of the extract from the pod was observed, resulting in turgidity primarily in the anterior region. A thickening of the cuticle was observed, as well as muscle degeneration in the caudal region and the digestive system. Deterioration of the cuticle and muscle in the caudal region was also evident. Albendazole demonstrated lysis across the larval stage, accompanied by the decomposition of the entire digestive system, muscle deterioration, cuticle degradation, and pod ruptures in various regions of the body. Given the absence of compounds in the water sample, no discernible morphological alterations were observed.

Figure 1.

Larvae exposed to Piper auritum and Capsicum annuum extracts, water and albendazole, after 32 hours. Morphological alterations were observed in the larvae exposed to the treatments. It has been demonstrated that exposure to Piper auritum results in the infiltration of the extract through the pod, accompanied by deformations in the cuticle. Furthermore, muscle deterioration was observed throughout the body and digestive tract. In the case of Capsicum annuum, the transfer of the extract from the pod was observed, resulting in turgidity primarily in the anterior region. A thickening of the cuticle was observed, as well as muscle degeneration in the caudal region and the digestive system. Deterioration of the cuticle and muscle in the caudal region was also evident. Albendazole demonstrated lysis across the larval stage, accompanied by the decomposition of the entire digestive system, muscle deterioration, cuticle degradation, and pod ruptures in various regions of the body. Given the absence of compounds in the water sample, no discernible morphological alterations were observed.

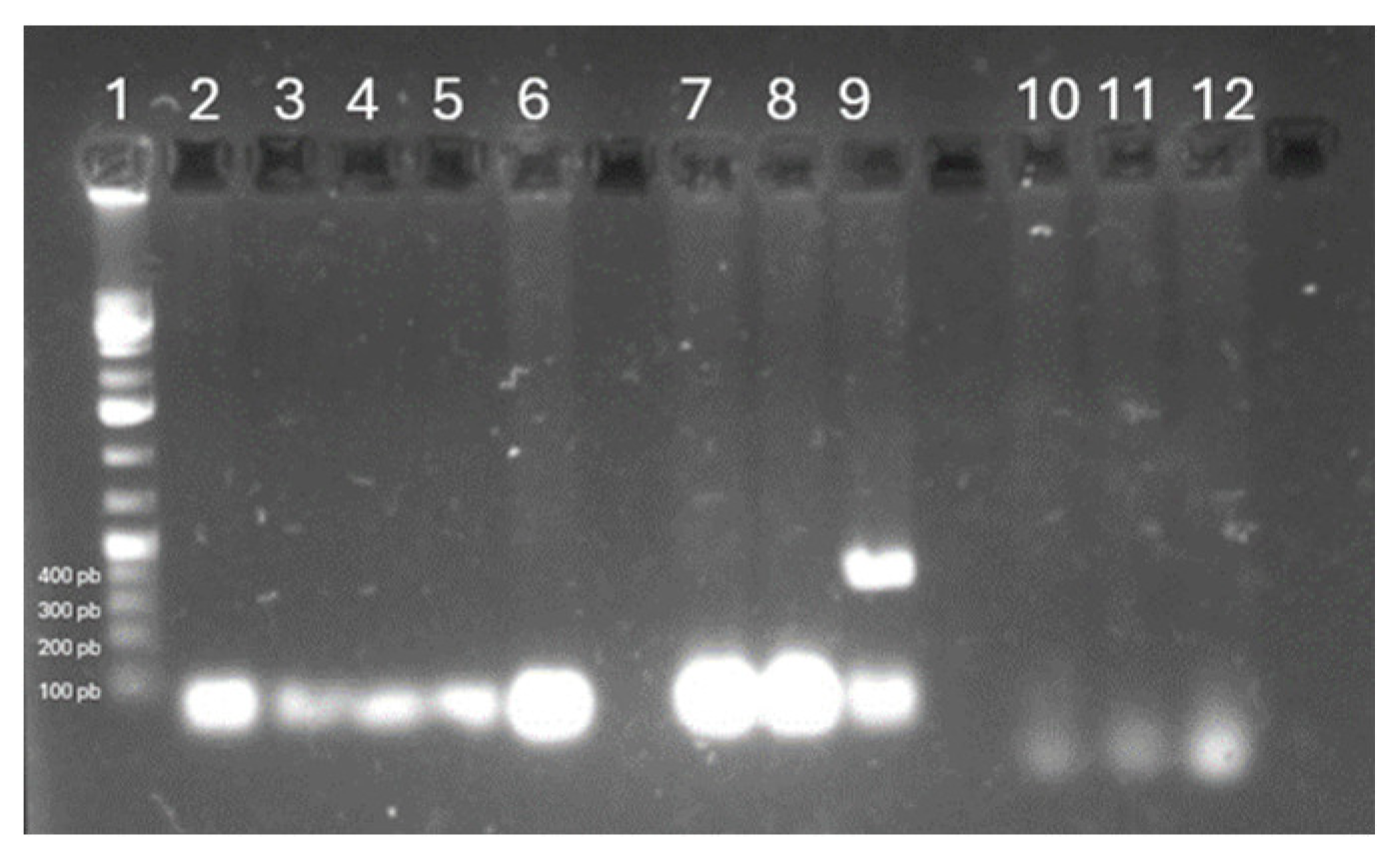

3.3. Nematodes Identified

Figure 2 shows the agarose gel electrophoresis profile of the gene fragments of the nematode species used. Lane 1 contained the molecular marker, lane 2 the negative control, water with PCR reagent mix was used, lanes 3-6 show the PCR products of

Oesophagostomum spp., then lanes 7-9 the PCR products of

Haemonchus spp. and lanes 10-12 the PCR products of

Trichostrongylus spp. This analysis resulted negative for the presence of

Oesophagostomum spp. and

Trichostrongylus spp., but

Haemonchus spp. was detectable.

4. Discussion

Plants and extracts have long been used in ethnoveterinary medicine to treat diseases in domestic animals [

23]. Furthermore, it has been studied that small ruminants can self-medicate against nematodosis by consuming specific plants [

24]. For these reasons, the plants evaluated in the present study were chosen because they are used in traditional medicine as dewormers for ruminants.

In vitro product testing is widely used in veterinary parasitology in the search for new anthelmintic active ingredients for use in ruminants, due to its low cost, direct contact of the compounds with the parasites, simplicity, and rapid results [

25]. However, there may be divergence when used in vivo, since the compounds can be affected by physiological processes of metabolism or by the ruminal microbiota [

26]. Furthermore, when administering anthelmintic plants in vivo, it is complex to dose a specific amount of bioactive compounds compared to solvent extraction.

Several in vitro studies with hydroalcoholic extracts show larvicidal effects of L3 on gastrointestinal nematodes in goats and sheep. 50 mg mL

-1 of

Cyrtocarpa procera extract showed a 50 % larvicidal effect against

Haemonchus contortus [

27], also, with the

Leucaena leucocephala pod extract at a dose of 50 mg mL

-1 killed 22 % of larvae, most frequently in

Haemonchus contortus and

Cooperia spp. [

28], also, it is reported that 100 mg mL

-1 of extracts of

Pluchea sericea and

Artemisia tridentata achieved 92.67 and 83% mortality of larvae [

21] respectively, similarly, with doses of 6.25 mg mL

-1 and 200 mg mL

-1 of

Acacia cochliacantha extract achieved 22 and 100 % mortality of

Haemonchus contortus larvae respectively [

29]. These concentrations were higher with the doses of the plant extracts used in this study, and it is also deduced that they have a greater larvicidal effect on

Haemonchus spp, a nematode of great importance because it is hematophagous.

A similar study with low doses of extracts was studied with tropical legumes, with 1,200 μg mL

-1, 35 % inhibition of larval migration of

Haemonchus contortus was achieved [

30]. In the present study it was demonstrated that the effectiveness of the plants used dependent on the availability of secondary metabolites, related to the conditions in which the plants were developed, phenological stage, parts used, as well as the seasons of the year in which they are collected [

14]. There is a history of in vitro evaluation of

Piper auritum against

Fasciola hepatica, with 500 μg mL

-1 an efficacy of 83 % of ovicidal activity was obtained [

31], however, there are few reports on the evaluation of

Capsicum annuum, as well as

Piper auritum as anthelmintics.

The anthelmintic potential of plants is attributed to the mechanisms of action of bioavailable compounds [

32]. Secondary metabolites can affect nematodes in various ways, such as damage to the cuticle, paralysis, starvation, growth, reproduction, among others [

33]. Tannins act on the glycoprotein of the cuticle and the proteins of the digestive tract, by binding to the receptors it causes autolysis [

34,

35]. Alkaloids intercalate into the microtubules of the cuticle, causing paralysis of helminth larvae; their improper use in in vivo tests can generate toxicity [

36,

37]. Flavonoids interact with the lipid bilayer of helminth membranes and interfere with protein transport processes, preventing energy production and effectively paralysis in larvae [

38]. They are also responsible for the inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation [

39]. Alkaloids block acetylcholine receptors and inhibit the transmission of nerve signals, resulting in paralysis of the larvae and subsequent death [

40]. Coumarin acts to block larval hatching, which suggests that it acts as a marker of bioactivity [

41]. The larvicidal effect of the extracts used is associated with the mechanisms of action of the flavonoids, coumarins, alkaloids and tannins mentioned above.

5. Conclusions

Chromatography identified secondary compounds available in the plants Piper auritum and Capsicum annuum, which exhibited larvicidal activity against Haemonchus spp. in L3 goats, with concentration-dependent efficacy. These results suggest their use in vivo as a sustainable strategy for the control and treatment of parasitic infections in small ruminants. Consideration should also be given to isolating pure compounds and standardizing dosage and potential adverse effects.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.P.S.-M., A.M.-M. and H.M.R.-M.; methodology, A.P.S.-M., J. H.-B, H.M.R.-M. And D.E.A.-S.; software, H.U.B.-H.; validation, H.M.R.-M. and A.M.-M.; formal analysis, H.U.B.-H.; investigation, A.P.S.-M., A.M.-M. and H.M.R.-M.; resources, M.A.-C.; data curation, A.P.S.-M. and H.M.R.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.S.-M., A.M.-M. and H.M.R.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.P.S.-M., A.M.-M., T. S.-R. and H.M.R.-M; visualization, M.A.-C. and D.E.A.-S.; supervision, A.M.-M.; project administration, A.M.-M. and H.M.R.-M.; funding acquisition, H.M.R.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHITI) for the scholarship awarded to the first author during the Master’s program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Olmedo-Juárez, A.; De Jesús-Martínez, X.; RojasHernández, S.; Villa-Mancera, A.; Romero-Rosales, T.; Olivares-Pérez, J. Eclosion inhibition of Haemonchus contortus eggs with two extracts of Caesalpinia coriaria fruits. Bio Sciences Magazine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, S.; Dessì, G.; Tamponi, C.; Meloni, L.; Cavallo, L.; Mehmood, N.; Jacquiet, P.; Scala, A.; Cappai, M.G.; Varcasia, A. Practical guide for microscopic identification of infectious gastrointestinal nematode larvae in sheep from Sardinia, Italy, supported by molecular analysis. Parasites & Vectors 2021, 14, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, E.A.; Reinoso, P.M.; Espinosa, R.R.; Avello, O.E. In vitro anthelmintic activity of aqueous extracts obtained from the edible biomass of Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight et Arn. Journal of Animal Production 2020, 32, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Degla, L.H.; Kuiseu, J. , Olounlade, P.A.; Attindehou, S.; Hounzangbe-Adote, M.S.; Edorh, P.A.; Lagnika, L. Use of medicinal plants as alternative for the control of intestinal parasitosis: assessment and perspectives. Agrobiological Records 2022, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Santos, F.; Morais-Cerqueira, A.P.; Branco, A.; Moreira-Batatinha, M.J.; Borges-Botura, M. Anthelmintic activity of plants against gastrointestinal nematodes of goats: a review. Parasitology 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davuluri, T.; Chennuru, S.; Pathipati, M.; Krovvidi, S.; Rao, G.S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of three tropical plant extracts on Haemonchus contortus. Acta parasitologica 2020, 65, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, D.; Sagüés, F.; Passucci, J.; Späth, E.J.; Lloberas, M.M.; Saumell, C.A.; Moreno, F.C. In vitro antiparasitic efficacy of quebracho extract (Schinopsis balansae) on infective larvae of Haemonchus contortus of sheep. Rev Med Vet Zoot. 2021, 68, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenopoulus, K.V.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Katsarou, E.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Haemonchosis: A chal lenging parasitic infection of sheep and goats. Animals 2021, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez-Lujan, L.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.; Caja-Campos, C. In vitro effect of Cymbopogon citratus essential oil on the embryogenesis and viability of Trichuris ovis eggs. REBIOL 2022, 42, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumed, H.; Nigussie, D.R.; Musa, K.S.; Demissie, A.A. In vitro anthelmintic activity and phytochemical screening of crude extracts of three medicinal plants against Haemonchus contortus in sheep at Haramaya Municipal Abattoir, Eastern Hararghe. J Parasitol Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhan, M.; Gesses, T.; Kenubih, A.; Dejene, H.; Yayeh, M. Evaluation of anthelminthic activity of tropical taniferous plant extracts against Haemonchus contortus. Vet Med Research Reports 2020, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Garza, N.E.; Gomez-Flores, R.; Quintanilla-Licea, R.; Elizondo-Luévano, J.H.; Romo-Sáenz, C.I.; Marín, M.; Sánchez-Montejo, J.; Muro, A.; Peláez, R.; López-Abán, J. In vitro anthelmintic effect of mexican plant extracts and partitions against Trichinella spiralis and Strongyloides venezuelensis. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, M. , Kumar, P. Herbal anthelmintic agents: a narrative review. J Tradit Chin Med 2022, 42, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.J.; Garduño, R.G.; Torres, H.G.; Gutiérrez, C.S.; Gómez, V.V.; Reyes, M.F. In vitro anthelmintic effect of plant extracts on gastrointestinal nematodes of hair sheep. Agricultural Production and Sustainable Development 2015, 4, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Compendium of Municipal Geographic Information. San Cristóbal Amatlán, Oaxaca. 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=07000020#collapse-Resumen.

- Cabrera, F.J. Primary identification of secondary metabolites of Ulex europaeus (thorny broom) and their biological activity. Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá D.C. 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14625/35016.

- Rodino, S.; Butu, M. Herbal Extracts - New Trends in Functional and Medicinal Beverages. Functional and Medicinal Beverages 2019, 73–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.M.; Pinto, N.B.; Moura, M.Q.; Villela, M.M.; Capella, G.A.; Freitag, R.A.; Berne, M.E. Antihelminthic action of the Anethum graveolens essential oil on Haemonchus contortus eggs and larvae. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2021, 81, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupo-Blanco, Y.G.; Burgueño-Tapia, E.M.; Vargas-Batis, B. Identification of compounds with antifungal action in leaf extracts of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour) Spreng. Cuban Journal of Chemistry 2024, 36, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Martínez, A.P. Techniques for obtaining and cultivating L3 larvae of gastrointestinal nematodes in ruminants. Veterinary Sciences and Animal Production 2024, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck-Montero, R.; Avendaño-Reyes, L.; Ail-Catzim, C.E.; Cuéllar-Ordaz, J.; Muñoz-Tenería, F.; Macías-Cruz, U. Ovicidal and larvicidal activity of aqueous extracts of Pluchea sericea and Artemisia tridentata in Haemonchus contortus. Ecosystems and Agricultural Resources 2018, 5, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, E.; Núñez-Romero, Y.A.; Mojena-Guerra, Y.; Fung-Boix, Y.; Fonseca-Turruella, Y. Phytochemical analysis of aerial parts of Sida pyramidata Cav. aura herb. Cuban Journal of Chemistry 2021, 33, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hoste, H.; Torres-Acosta, J.F. Nonchemical control of helminths in ruminants: adapting solutions for changing worms in a changing world. Veterinary Parasitology 2011, 180, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanelli, F.; Mattellini, M.; Fichi, G.; Flamini, G.; Perrucci, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of four plant-derived compounds against ovine gastrointestinal nematodes. Veterinary Sciences 2018, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, S.; Feyera, T.; Assefa, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of aerial parts of Cissus quadrangularis L. and leaves of Schinus molle L. against Haemonchus contortus. BioMed research international 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.E.; Castro, P.M.N.; Chagas, A.D.S.; França, S.C.; Beleboni, R.O. In vitro anthelmintic activity of aqueous leaf extract of Annona muricata L.(Annonaceae) against Haemonchus contortus from sheep. Experimental parasitology 2013, 134, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús-Martínez, X.; Rivero-Pérez, N.; Zamilpa, A.; González-Cortazar, M.; Olivares-Pérez, J.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; Mendoza-de Gives, P.; Villa-Mancera, A.; Olmedo-Juárez, A. In vitro ovicidal and larvicidal activity of a hydroalcoholic extract and its fractions from Cyrtocarpa procera fruits on Haemonchus contortus. Exp Parasitol. 2024, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Perez, N.; Jaramillo-Colmenero, A.; Peláez-Acero, A.; Rivas-Jacobo, M.; Ballesteros-Rodea, G.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A. Anthelmintic activity of Leucaena leucocephala sheath against ovine gastrointestinal nematodes (in vitro). Abanico veterinaria 2019, 9, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Rojo-Rubio, R.; Zamilpa, A.; Mendoza de Gives, P.; Arece-García, J. , López-Arellano, M.E. In vitro larvicidal effect of a hydroalcoholic extract from Acacia cochliacantha leaf against ruminant parasitic nematodes. Veterinary Research Communications 2017, 41, 227–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son-de Fernex, E.; Alonso-Díaz, M.A.; Valles-de la Mora, B.; Capetillo-Leal, C.M. In vitro anthelmintic activity of five tropical legumes on the exsheathment and motility of Haemonchus contortus infective larvae. Experimental Parasitology 2012, 131, 413–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Mercado, J.M.; Ibarra-Velarde, F. , Alonso-Díaz, M.Á., Vera-Montenegro, Y.; Avila-Acevedo, J.G.; García-Bores, A.M. In vitro anthelmintic effect of fifteen tropical plant extracts on excysted flukes of Fasciola hepatica. BMC veterinary research 2015, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.; Brygadyrenko, V. Survival of nematode larvae Strongyloides papillosus and Haemonchus contortus under the influence of various groups of organic compounds. Diversity 2023, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.D.; de Lima, H.G.; de Sousa, N.B.; de Jesus, G.I.L.; Uzêda, R.S.; Branco, A.; Botura, M.B. In vitro anthelmintic evaluation of three alkaloids against gastrointestinal nematodes of goats. Veterinary Parasitology 2021, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, K.; Kakoti, B.B.; Borah, S.M.; Kumar, M. Evaluation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of Heliotropium indicum Linn. leaves in Indian adult earthworm. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2014, 4, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, A.; Silvino, R.; Sánchez, L.M.; Bongo, A.L.; Simões, C.; Lucombo, M.D.; Cunga, A.; Inácio, E. In vivo anthelmintic activity of Tephrosia vogelii on gastrointestinal strongylids in naturally infected goats. Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2021, 43, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, D.; Ashraf, S. M.; Mohan, L.; Rathinasamy, K. Berberine induces toxicity in HeLa cells by disrupting microtubule polymerization by binding to tubulin at a unique site. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2594–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Sharma, B. Toxicological effects of berberine and sanguinarine. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Núñez, E.J.; Zamilpa, A.; González-Cortazar, M.; Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Cardoso-Taketa, A.; Sánchez-Mendoza, E.; Tapia-Maruri, D.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.O.; Mendoza, G.P. Isorhamnetin: a nematocidal flavonoid from prosopis laevigata leaves against Haemonchus contortus eggs and larvae. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibou, M.; Hamadou, H.H.; Moussa, A.N.; Bamba, Z.C.O.; Idrissa, M.; Tanimoune, A.; Ikhiri, K. In vitro study of the anthelmintic effects of ethanolic extracts of Bauhinia rufrescens Lam.(Fabaceae) and Chrozophora brocchiana (Vis) Schweinf (Euphorbiaceae) two plants used as antiparasitic in Azawagh area in Niger. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2020, 9, 944–948. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, O.; Allanic, C.; Charvet, C.L. Lupin (Lupinus spp.) seeds exerted anthelmintic activity associated with their alkaloid content. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escareño-Díaz, S.; Alonso-Díaz, M.A.; de Gives, P.M.; Castillo-Gallegos, E.; Von Son-de Fernex, E. Anthelmintic-like activity of polyphenolic compounds and their interactions against the cattle nematode Cooperia punctata. Veterinary Parasitology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).