1. Introduction

With the advancement of economic development and growing societal demands, numerous complex micropollutants are increasingly entering natural ecosystems. Water contamination is a significant global concern and one of the major contributors to environmental degradation. Therefore, water quality monitoring is a common practice globally, essential for quality management and planning. Water monitoring has gained the interest of researchers even more during this period. Monitoring activities are essential for identifying polluted sources, and managing them afterward, and are fundamental components of water and environmental planning [

1,

2,

3]. Water quality monitoring (WQM) contributes to the foundation of pollution control, and the ongoing real-time feedback it provides is directly linked to the consequences of pollution events. The monitoring of water quality enables the verification of regulatory compliance and helps mitigate the risks associated with degrading water quality [

4].

Though water monitoring activities are essential management and planning tools, they are facing several challenges [

5]. The complex interplay of structural, operational, and water quality parameters, along with the uncertainties, presents a challenge when it comes to establishing effective monitoring programs [

4]. Various valuable strategies aimed at improving WQM plans and programs have already been suggested or recommended thus far. For instance, Barcellos and Souza [

5] have designed data mining-based programs to minimize the parameters for water quality monitoring. However, current WQM programs still have disadvantages such as lack of precision, consumption of unsustainable energy, fragility, manual calibration, needs, and high costs for maintenance [

2,

6].

Blockchain technology (BCT) is normally determined as one of the most significant innovations of the 21st century. Among the emerging engineered technologies, blockchain stands out as a flexible solution that combines smart contracts, Big Data, IoT, distributed ledgers, and artificial intelligence (AI). This integrated technology can find applications in intelligent waste control and management [

7,

8]. Blockchain applications are often designed based on a peer-to-peer (P2P) framework, enabling organizations to exchange information, goods, and services without relying on central authorities to verify identity, validate transactions, enforce commitments, or involve intermediaries etc. The blockchain serves as a distributed database with a decentralized structure [

9]. Its data structure comprises a series of data blocks interconnected chronologically along a chain [

10]. Cryptography ensures security for the transfer of data.

Blockchain is a collectively maintained, decentralized ledger system primarily designed for secure and reliable data storage. The block consists of two main components: the “block header” and the “block body.” The “block header” stores essential metadata for the present block, involving the timestamp, the hash of the preceding block, and the Merkle root hash. Meanwhile, the “block body” contains the actual data information. Blockchain employs blocks, encryption for data storage, P2P logic networks, and consensus mechanisms to validate data and facilitate communication among distributed nodes. Blockchain has the potential to help address environmental challenges and promote ecological sustainability [

11]. Also, cost-effective IoT applications are recognized as reliable solutions for implementing blockchain-based water management in agriculture [

12]. Societal needs and development have increased the necessity to obtain real-time water quality information. Numerous studies and projects have been conducted in the field area for water contamination control. Smart agricultural irrigation is an emerging scientific field that utilizes data-intensive methods to boost agricultural productivity while concurrently mitigating adverse environmental effects [

13]. It began with the implementation of real-time water quality surveillance using the IoT within SCADA systems (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition), providing an effective solution for identifying water contamination in data acquisition systems and enabling real-time supervisory control [

14]. Additionally, the IoT-enhanced monitoring system is specifically engineered to address the challenge of water quality surveillance. It achieves this by creating a cost-effective, real-time solution comprising IoT sensors capable of measuring key water quality parameters such as pH, temperature, turbidity, and flow.

Real-time water monitoring by using IoT integrated Big Data helps alarm contaminated water sources [

15]. The proposed monitoring system of real-time water quality for rivers focuses on remotely monitoring water bodies, particularly rivers, and lakes, while integrating surveillance and an immediate notification system [

15]. Accessing real-time data is achievable through the utilization of remote monitoring and IoT technology. The integration of IoT with Big Data analytics appears to offer a superior solution, as it can deliver reliability, scalability, speed, and persistence. Blockchain is an innovative technology that has given rise to new technological advancements. BCT provides a robust and reliable solution for establishing an effective trust mechanism among all the stakeholders engaged in the utilization management of water resources [

10].

Leveraging a blockchain-based solution simplifies the issuance and monitoring of water abstraction permits, ensuring greater convenience and enhancing the security and verifiability of information. The system provides multiple advantages, such as dependable and secure storage of water resource data, efficient information transmission, and robust traceability of water quality issues. BCT can trace a pollution event’s origins, track its pathways, and ultimately identify the affected area, providing a comprehensive solution for pollution monitoring and accountability [

16]. The innovative framework presented in this study combines blockchain-based technology, a wireless sensor network (WSN) arranged in a directed acyclic graph (DAG) configuration, and a Geographic Information System (GIS) to track contamination pathways starting from irrigation water intake data. After mapping a contaminated irrigation unit using GIS and following the blockchain tracing process, a Water Quality Analysis Simulation Program (WASP) is employed for real-time data, aiding in the identification of potential pollution sources involved in wastewater discharge illegally. Further, several studies have

suggested a blockchain-based framework for managing industrial wastewater [

17,

18] and a system of wastewater recycling [

19]. For example, when compared to existing models, the proposed IoT-based wastewater management system designed for smart cities (IoT-WMS) dedicated to wastewater treatment and recycling, accomplished impressive results, including a wastewater recycling rate of 96.3%, an efficiency of 88.7%, and a notable increase in wastewater reuse, reaching 90.8% [

18]. Berlian, Sahputra [

20] introduced a real-time system framework for smart environment monitoring and analytics based on the Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) and Big Data technologies. They utilized an integrated IoUT (Internet of Underwater Things) environment system coupled with a comprehensive Big Data framework, incorporating an open-platform data processing system. This system gathers and archives data concerning various parameters—such as oxidation-reducing potential, electrical conductivity (EC), pH, total dissolved solids (TSS), salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), and temperature—from a remotely operated vehicle. The advantage of combining IoT and Big Data in water management is the capability to detect and accurately measure the levels of chemical residues present in the water.

Indeed, IoT and Big Data offer multiple avenues for enhancing water management. These technologies can improve various aspects, such as water resource management, WQM, and security in water-related operations. Overall, water monitoring systems do face specific challenges, which can hinder the efficient sharing and delivery of information. Traditional approaches to monitoring water quality involve manual and continuous methods, which are expensive and less efficient [

21]. Accurately monitoring this process poses challenges, leading to increased costs associated with data verification. BCT has the potential to address these issues effectively. By leveraging its robust network and continuously integrating processes and data, this system enhances data reliability and transmission efficiency.

Additionally, BCT contributes to establishing trust and enabling secure information sharing at a cost-effective rate. The introduction of BCT in conjunction with the IoT is a promising approach that can offer real-time monitoring and significantly enhance the efficiency of data collection. Big data combined with IoT sensors and applications play a crucial role in collecting data that enables effective technological solutions [

18,

22]. The proposed systems are expected to offer an improved solution for monitoring water quality and enabling users to interact with, retrieve, and analyze both real-time and historical data. As the value of BCT has become widely reported, a growing number of industrial areas are actively exploring and implementing blockchain solutions.

Nevertheless, there are still relatively few practical applications of BCT in the domain of water resource utilization and management. Hence, a thorough investigation into how to effectively integrate BCT with water management is required. It is crucial to research how emerging BCT can be applied to optimize current water quality management and monitoring practices. Furthermore, this paper also aimed to conduct an economic feasibility analysis of applying BTC in WQM. The conclusions drawn in this work provide valuable insights and highlight the challenges that need to be addressed for prospects in the optimization of WQM.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 6) define water as a basic human right and essential to sustainable development. It emphasizes the importance of improving

water quality by reducing pollution and increasing wastewater treatment [

23]. The SGG 6 also emphasizes

water-use efficiency and ensures sustainable withdrawals to address water scarcity. This paper contributes by providing a synthesis and critical analysis of BT as well as proposing a new framework in water quality monitoring.

2. Blockchain Technology for Water Resources Protection and Irrigation

2.1. Hydrology & Water Resources for Our Human Life

Water resources are crucial in human life sustainability in various aspects. First, human needs clean and safe water for drinking, domestic use, and sanitation. Safe and clean water is especially important during disasters and pandemics when water is highly prone to water-borne diseases. Therefore, maintaining a sustainable water supply system is the key for human beings. Second, water provides an essential source for agriculture and aquaculture to safeguard food security and livelihoods for the world’s population. Agriculture and aquaculture are indeed the greatest consumers of global water resources, mainly through irrigation and water supply systems, which are constantly maintained by the investors. Third, water is used to generate electricity in hydropower plants. Hydropower is the largest renewable energy which favors clean operation, low greenhouse gas emissions, and long-term sustainability [

24]. Globally, over 47,000 hydropower dams have been built [

25], of which 64 large dams were built in the Mekong River Basin [

26]. Therefore, hydropower is an important component of sustainable energy [

27]. Fourth, water provides a base for aquatic organisms and wetland ecosystems, supporting fishery. Fifth, water is essential for industry development because almost all products need water in the manufacturing processes. Water resources are changing because of the natural changes in the hydrological system [

28], being intensified by the effects of climate change and human interventions [

29]. Human-induced climate change is expected to increase precipitation in some places but decrease precipitation in others. Therefore, climate change has been predicted to increase the magnitude, duration, and frequency of climatic extremes, such as extreme floods and droughts [

30]. In other words, climate change will likely cause the wet areas to become wetter and the dry areas to become drier. Extreme floods are expected to increase in temperate and tropical regions [

31], while extreme droughts are expected to increase in Northern, Western, and Southern Africa, the Caribbean, Central America, southern Europe, Australia, and West Asia because of a decrease in precipitation and an increase in temperature [

32]. Consequently, crop yield may be decreased under more frequent and prolonged droughts, causing food insecurity, whereas human lives and infrastructures are at risk under more severe floods caused by climate change [

33].

Given the importance of climate change in water resources management, many studies have examined the effect of climate change on flow regimes and sediment load. In the Mekong, climate change is predicted to increase flooding in the future [

34]. Similarly, climate change will likely be the main driver of flow regime alterations in the Upper Yellow River [

35] and the Upper Yangtze River [

36]. In Thailand, [

37] found that the 100-year flood and drought in the Upper Chao Phraya basin are projected to increase by 1.63 and 0.59 times, respectively, under the SSP126 scenario, and by 4.55 and 1.56 times, respectively, under the SSP370 scenario. They also found that the combinational effect of climate and land use changes is likely to result in more severe water shortage and frequent floods and droughts in the basin. In large rivers in South America, climate change is projected to decrease the rainfall in the 21st century, thus reducing flooding [

38]. However, the signal of climate change’s effect on flooding in Europe is not clear; while some areas are forecasted to decrease (e.g., 23% per decade), others are forecasted to increase (e.g., 11% per decade) [

39].

Human has also increasingly affected water resources and hydrological systems through two main activities: dam construction and land use change. Dams and reservoirs provide effective flow regime regulation by increasing the dry-season flow and reducing the flood-season flow, thus reducing the risk of floods and droughts. Even though hydropower dams strongly regulate seasonal flow regimes, the effect on the annual flow is small [

40]. For instance, at the Chiang Saen hydrological station in the Mekong River, the discharge decreased by up to 46% in the flood season and increased by up to 187% in the dry season due to upstream dam operations [

41]. Principally, dams and reservoirs can dampen climate-driven flow regime alterations [

42]. However, they cannot fully eliminate the flood and drought risks under the future changing climate [

29], given that the capacity of reservoirs is relatively small compared to the effect of climate change. Under that situation, dams may exacerbate the flooding issues in the basin [

43]. Besides that, dams trap sediment in the reservoirs, leading to the so-called “hungry water” downstream. Consequently, river geomorphology is degraded through riverbank erosion and riverbed incision. In the Mekong, for instance, dams have reduced about 74% of the sediment load in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta between 2012-2015 and pre-1992 [

40], causing large-scale riverbed incision which has led to an increase in salinity intrusion in the delta [

44].

On the other hand, land use change via deforestation and urbanization are the two key drivers to enhance the magnitude and frequency of flooding by increasing the runoff coefficient [

45]. Moreover, deforestation may have increased droughts because of a reduction in the infiltration rate during the wet season, thus leading to less soil moisture and the baseflow in the subsequent dry season. Collectively, dams and land use change are found to dominate flow regime alterations in many river basins, exceeding the effect of climate change [

26]. Because the cumulative effect of climate change and human activities on hydrology and water resources is complicated, an effective methodology for prediction and protection is needed, and blockchain technology emerges as a promising tool.

2.2. Blockchain Technology for Water Resource Sprotection and Irrigation

Long-term data is crucial for comprehensively understanding the complex hydrology and water resources on Earth. The data needs to be reliable, secure, and standardized, from which scientists can produce reliable and accurate hydrological forecasts for successful disaster risk management. Therefore, blockchain technology provides an advanced database platform and mechanism for secured data storage and data sharing because it can track the recorded data, data exchange, and extraction, while the data cannot be deleted or changed in the network.

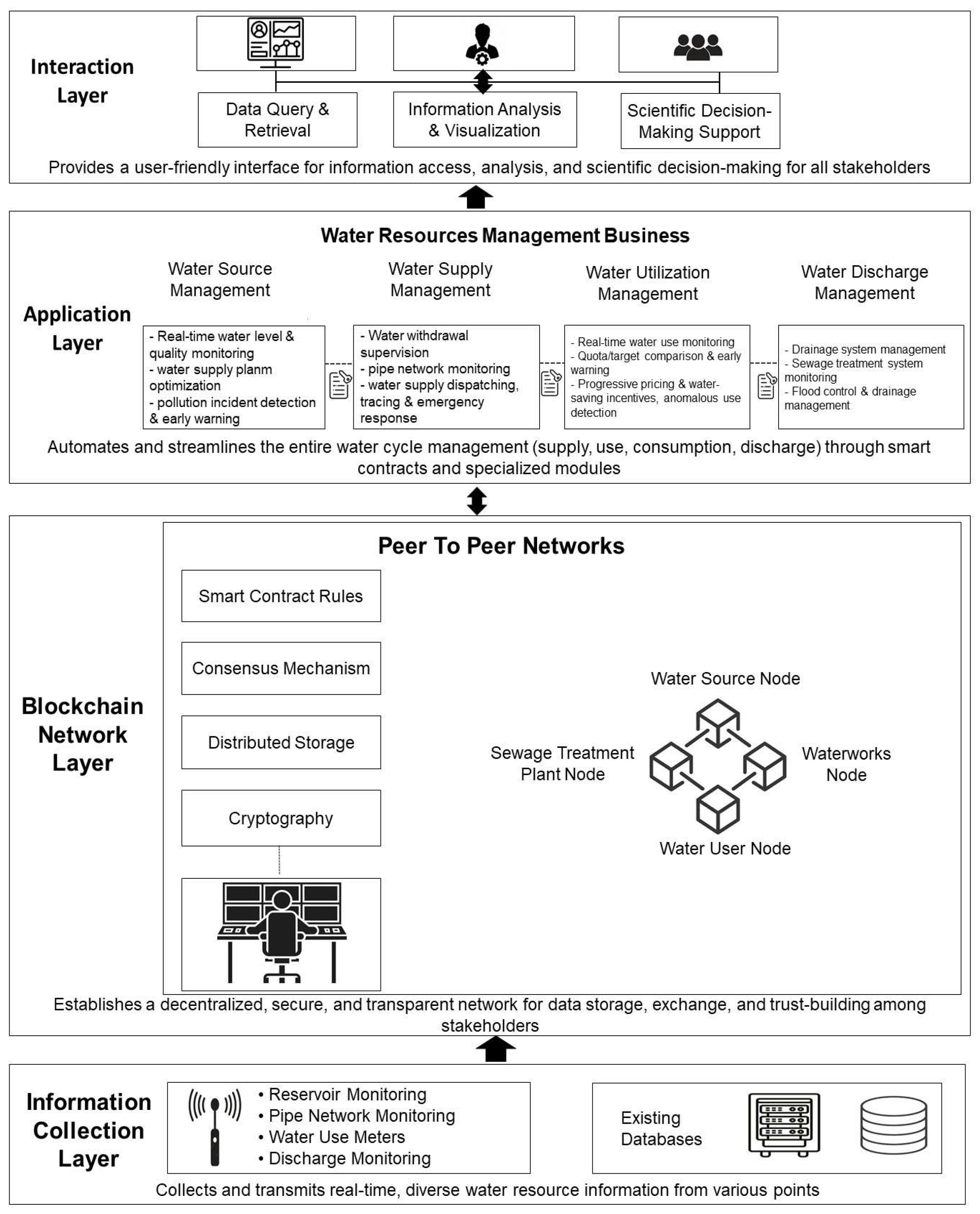

Figure 1 shows that there should be four layers in the blockchain-based water resources management system. The first layer is data collection and transmission, which uses in-situ sensors for monitoring and IoT and wireless technology for data transmission. The blockchain network is then used for data distribution in terms of blocks to ensure data security, accessibility, and transferability. The application layer executes the water resources management business from the system function, whereas the interaction layer allows the exchange between the water resources management system and external/internal management/service portals. Blockchain technology can be applied to smart water governance by developing cryptocurrencies and smart contracts for water resource conservation. Blockchain technology was examined to provide a framework and architecture for water resources management and solutions for water quality [

46]. Blockchain technology can be incorporated with smart water management to revolutionize water and sanitation governance if the solutions are creative, efficient, and scalable [

47]. Drought risk management can be enhanced by using blockchain-based frameworks after understanding spatiotemporal drought distribution and severity, from which the affected citizens can receive timely assistance [

48]. Moreover, blockchain incorporated with big data can be used to bridge locally used solutions with global infrastructure systems for effective water governance [

49]. Water resource protection can be enhanced by applying blockchain to store the data of water bodies, to collaborate between sectors, and to increase public involvement levels [

50]. The way blockchain manages the data is that it allows all data from the watershed monitoring system to be integrated with those from direct measurements of water usage from all system users. For instance, [

51] used blockchain technology for downstream flood prediction by integrating upstream monitoring networks and dam inflow prediction. Blockchain can also be used in hydropower dam operations [

52], groundwater management [

53], and water consumption [

54] by storing the encrypted operational data on the chain.

Agriculture provides vital food for human beings. Under rapid agricultural development, the need for agricultural data acquisition, data collection, data storage, and data transmission is increasing. However, there lack of a reliable platform for agricultural information systems, mainly in developing countries, which may suffer from data leakage and cyberattacks [

56]. Consequently, the operations of the irrigation system may fail, which may cause unreliable and misleading decision-making processes. That may eventually lead to the reduction of agricultural production, affecting the food chain and even food security. The use of blockchain technology, which can integrate with the Internet of Things, may address this problem by ensuring data rights and preventing data duplication [

56]. Blockchain technology can be applied for data tracking and recordings, such as the farm, the irrigation systems, the hydraulic structures in the systems, the farmer, soil, and water [

57]. Therefore, irrigation systems and agricultural management can be autonomous, smart, and secure.

Blockchain technology can support better agricultural water management to maximize agricultural products by providing optimized use of water, fertilizer, and pesticide, thus maximizing the farmers’ net income. Traditional agricultural practices, which are ineffective in water resources management [

58], should thus be transformed into smart agricultural systems through blockchain-based digital solutions [

59]. Smart irrigation systems based on blockchain technology can be established by securely monitoring, storing, and operating data for water quality and quantity, air quality, meteorology [

60], dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity [

61], agricultural supply and demand, soil moisture, and temperature [

58]. In smart irrigation systems, farmers can maximize benefits while minimizing costs by reducing the use of artificial pesticides and fertilizers, thus reducing the pollution of water and soil. For that, the monitored data for insects and soil fertility are transmitted to the server, which is then compared with the thresholds to send the order of using the pesticide and fertilizer or not. This principle is also applicable to other physicochemical parameters in irrigation systems, such as water, humidity, and soil moisture for issuing the command for plant watering.

Munir, M.S [

62] developed a smart watering system for small and medium gardens and fields in Pakistan by combining blockchain technology with a fuzzy logic approach. The real-time data of plants and environment (e.g., soil moisture, light intensity, air humidity, and temperature) are collected from accessible and economical sensors. The collected data are securely managed by blockchain technology, while the decision on the smart watering schedule is operated by fuzzy logic by comparing the plants’ water demand with the real-time monitored parameters. Once ordered, the smart watering system will activate actuators to water plants by periodically turning water tunnels.

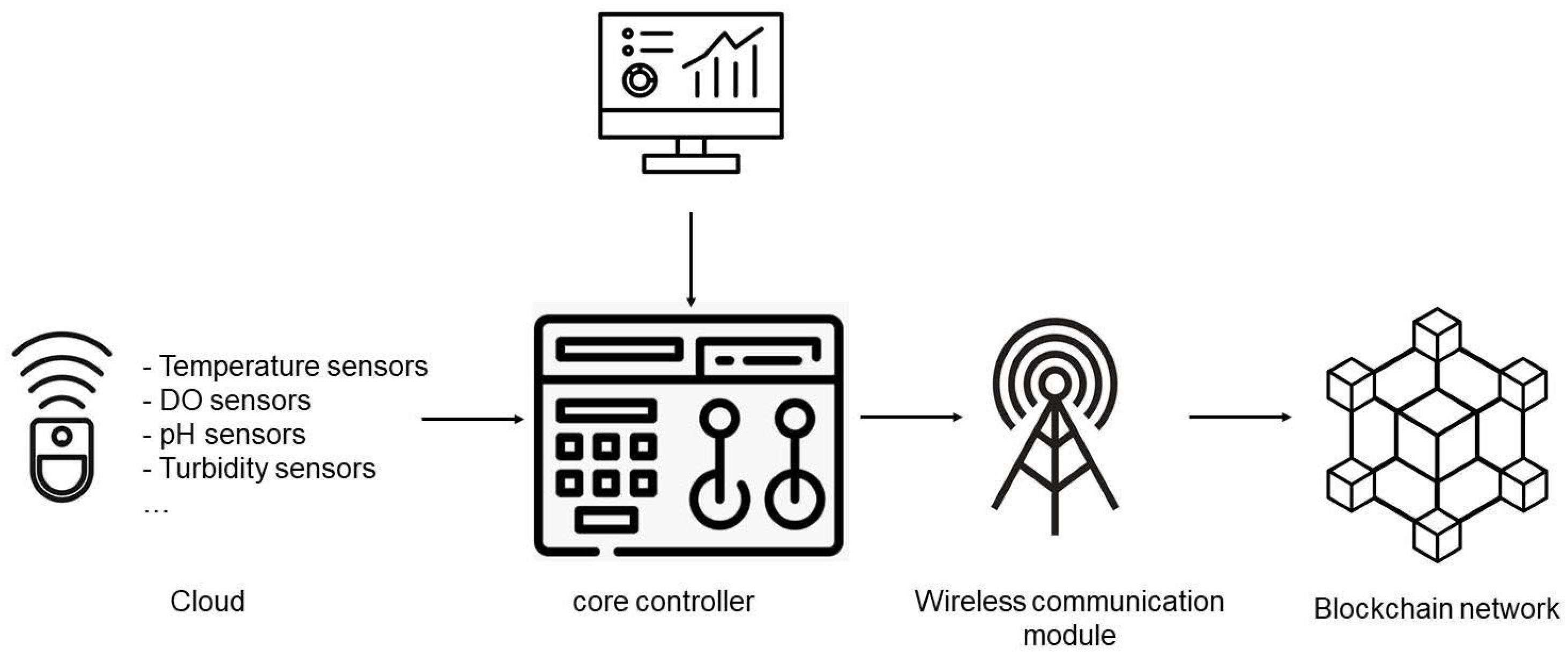

Figure 2 shows the structure of the smart watering system using a blockchain-based IoT model. This framework allows communication between smart devices (e.g., smartphones), sensors (e.g., for temperature and soil moisture), actuators and cloud storage, users, and networks. Farmers can easily operate this system with a mobile app on their Android smartphones. Therefore, this smart watering system may reduce the cost and enhance the yield, thus increasing farmers’ net revenue.

3. Application of Blockchain Technology in Water Quality Monitoring

Over the past few years, water pollution has emerged as a growing concern worldwide. As a fundamental resource for all living beings, maintenance of water quality is crucial. This part reviews surface water quality monitoring programs based on blockchain technology for viable, safe, and clean water use. As usual, a model of the Internet of Things (IoT) is applied to arrange water quality measurements, which are subsequently uploaded to the cloud. Then, Blockchain technology is implemented to prevent any potential tampering with this database [

63].

3.1. An Overview of Targets

3.1.1. Overview of Water Quality Monitoring

Water management is a fascinating and critical topic that has gained increasing attention in recent years. Within many proposals that serve for scope of optimizing water consumption and administration, water monitoring is the most interesting theme. According to the European framework, a water monitoring program is a systematic process of sample collection and analysis, data processing, and presenting the status and trends of water sources [

64]. Water monitoring programs aim to assess the water body’s quality and pollution levels, and some of them also involve collecting samples from other parts of the aquatic ecosystem, such as the sediment and the particulate matter, to analyze the pollutants [

65]. Water monitoring is necessary because drinking water sources and ecosystem health depend on human efforts to protect water sources and improve their understanding [

66]. Water monitoring is necessary because drinking water sources and ecosystem health depend on human efforts to protect water sources and improve their understanding [

67]. Results from a water monitoring program can also provide to decision-makers for water administration and protection [

67]. Water monitoring can be applied in various types of water sources such as surface water (rivers, lakes, reservoirs, etc.), groundwater (aquifers, wells, springs, etc.), and coastal and marine water (estuaries, bays, oceans, etc.). A water monitoring program can indicate various quality parameters of physical (temperature, turbidity, etc.), chemical (pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, metals, etc.), biological (bacilli, actinomycetes, algae, etc.), and ecological (macroinvertebrates, algae, etc.) [

68].

For surface water, a monitoring program is a systematic approach to collecting and analyzing a database of surface water quality across a certain area. The program aims to assess the status of water quality by collecting water samples from rivers, streams, and lakes and analyzing these samples. The program typically includes a protocol for designing and implementing monitoring of surface water, provides information on how to collect and analyze water samples, including the standard methods used for sampling and analysis, and well as guidance on how to present the results [

69]. The monitoring data that is collected can help to evaluate how the aquatic systems’ physical, chemical, and biological features affect human health, ecological conditions, and intended uses [

70]. Different scales of surface water monitoring programs can be carried out, such as at the local, national, regional, or global level. On a global scale, the WHO - UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene estimates the percentage of households that have safe access to drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene services, according to the 6th Sustainable Development Goal for Wate [

71]. Another Canada-B.C. Water Quality Monitoring Program collects and produces aquatic information on British Columbia’s water sources for freshwater resource managers and Canadians [

72]. The Mekong River Commission Water Quality Monitoring Network detects changes in water quality and takes action as necessary throughout the Mekong Basin [

73].

3.1.2. Overview of Blockchain

Blockchain - the most popular technology was initially introduced through Bitcoin, which remains its most successful application to date. A blockchain is a distributed ledger that consists of a series of blocks, each of which contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block. If a block’s content is altered, its hash value changes, necessitating changes in all following blocks. Given the distributed nature of the network, modifying the data stored by all nodes is virtually impossible, rendering the blockchain immutable. A comprehensive blockchain system incorporates various technologies including encoding, Peer-to-Peer (P2P), and workload authentication. The data chain is protected by encryption technology, while P2P creates a decentralized system based on the blockchain, which solves the problem of consistency by using proof of work [

74,

75].

Blockchain technology can be divided into three types of access: public chain, alliance chain, and private chain [

76].

Public chain: allows any node to join or leave without any permission. There is no central authority or any individual or organizational restriction for all nodes. Ethereum and Bitcoin are the most common examples of public chains. Alliance chain: restricts the participation to only the members of the alliance, and usually requires the support of certification agencies. Members who join the alliance will be verified, and each node needs to be authenticated. Super Magic and R3Corda are typical applications of alliance chains.

Private chain: all write permissions are granted to one organization, and this sole organization can set rules arbitrarily in typical conditions. Private chains are used within a company to increase the speed of business, but they sacrifice some decentralization functions.

Blockchain technology can enhance the value and reliability of large-scale database storage for water quality monitoring processes. Blockchain can provide data validation, transparency, and integrity in an automated way [

77].

3.2. Blockchain Approach for Water Quality Monitoring

Water resource management can benefit from cyber-physical systems (CPS) applications that improve water sustainability, efficiency, automation, and consumer confidence. A key application of CPSs in this field is water distribution system monitoring. This application can track water quality parameters continuously and send alerts when the system detects an anomaly. This CPS can help maintain water quality balance or protect consumer health by identifying water-related problems [

78]. Working as a decentralized P2P network, blockchain serves as the security part of cyber-physical systems. Pahontu [

79] suggested using Ethereum to report the cyber-physical database of water quality monitoring. In this scheme, users can report a water distribution network fact through the crowdsensing application. The application saves the fact in its relational database and rewards the user with a digital token. The user gets the token from the blockchain through a transfer process of the administrator’s wallet to the user’s wallet. The user can use their wallet to buy, sell, or donate tokens as they wish. The user can also use their tokens to buy contract subscriptions which are discounts from the marketplace section. An ERC-1155 token is stored in the blockchain as a representation of the discount. The user exchanges their water game tokens (WGT) for a discount token that updates the physical discount in the relational database but without the guidelines from the manager. The system constantly checks the users’ digital discounts and updates the physical ones in their database. The user can also use blockchain to exchange both WGT tokens and digital discounts on other transaction platforms.

Ortiz [

80] mentioned that using blockchain to collect water data can raise public awareness of water quality issues in Puerto Rico. For the achievement of water quality traceability, a monitoring system using low-cost sensors was designed. The low-power wide-area network (LPWAN) is a technology that allows data to be transmitted with low energy consumption and long range. The data is then stored in a blockchain that does not require entrust. Another study recorded that blockchain is ideal for developing smart contracts that manage a market of “quality credits” that reward the participating entities economically and benefit the environment by increasing the average water quality over time [

81].

To motivate citizens to participate in water monitoring programs, crowdsensing platforms can be used as tools to motivate people. Fascista [

82] suggested it could be gathering and distributing real-time information on water quality and water consumption, and encouraging a collaborative way of managing water sources. Blockchain enhances the reliability of crowdsensing platforms in large-scale monitoring procedures by providing automated data validation that complements the incentive mechanisms of crowdsensing serious games [

83]. Dogo explores the potential of using blockchain and IoT for water source management in the framework of climate change and rapid population growth. It also investigates how they can be used in different situations of managing stormwater in terms of water quality, and report directly to consumers and related interested parties [

84].

According to [

85], the water management blockchain framework consists of four modules managing water sources, supplying water, using water, and discharging water. The first module of water source management aims to ensure adequate water quality. Sensors record water quality data from water sources and store it in the node block. Smart contracts compare the recorded water quality data to the water quality targets and send the assessment results to the blockchain. It monitors the water quality and transmits the results in real-time to quickly identify water pollution status. The real-time data on the water quality of reservoirs helps to adjust water supply plans precisely and quickly.

Zhang, J.,[

86] studied applying blockchain technology in water management based on analyzing its current situation. The research aims to ensure data consistency and validity in a distributed setting by addressing the issue of data alignment. This procedure converts the management development system into a model of decision-making. The model presents all prediction results as interval numbers, which can aid in making more sensible decisions regarding water resource management. The model applies stochastic programming with interval uncertainty to characterize the system’s uncertainty and solve the uncertainty issue of water resource systems. The model uses blockchain techniques to make water source systems independent and interrelated objects. The system’s mechanism is the process where participants agree on consensus algorithms. Consensus mechanisms enable decentralized decision-making and governance through blockchain technology, which can enhance the optimal management of water resources. Participants can share decisions and manage the use of water sources through a consensus mechanism. This decentralized approach can cut down power, and limit centralization risk while increasing the fairness and effectiveness of decision-making. This incentive mechanism can encourage participants to participate and contribute actively and encourage the long-term preservation of water sources. To achieve this target, the model considers the interdependence of resources, circumstances, and other aspects with the help of blockchain technology.

Another project proposed by Cheng [

87] uses IoT devices to collect water monitoring data from sensor array circuits and send it to a platform that can access from a real-time Firebase mechanism and submit it to the NEM Symbol blockchain. The project also uses the Symbol SDK to create a web-based platform for water monitoring and management purposes. The sensors upload the water quality data to the cloud using Wemos D1 R32. The gateway webpage gets the data from the Firebase Database. The project uses Symbol XYM, which has an API that lets developers create any application they want. The gateway webpage combines the data into a string and stores it in the Symbol Blockchain using the transfer transaction API. The user can see the transaction that is recorded in the Symbol wallet. An [

88] created a platform that lets anyone monitor the water environment using registered devices and sensors. The system stores data from the sensors on a blockchain network called Hyperledger Fabric, which ensures that the data is secure, transparent, and accurate. Users can access and share their device data with others in real-time

3.3. A New System for Water Quality Parameters

BCT can be used to develop an efficient and reliable system in collecting and managing water quality data. Precisely, the combination of IoT-powered sensors and blockchain optimizes water quality data collection.

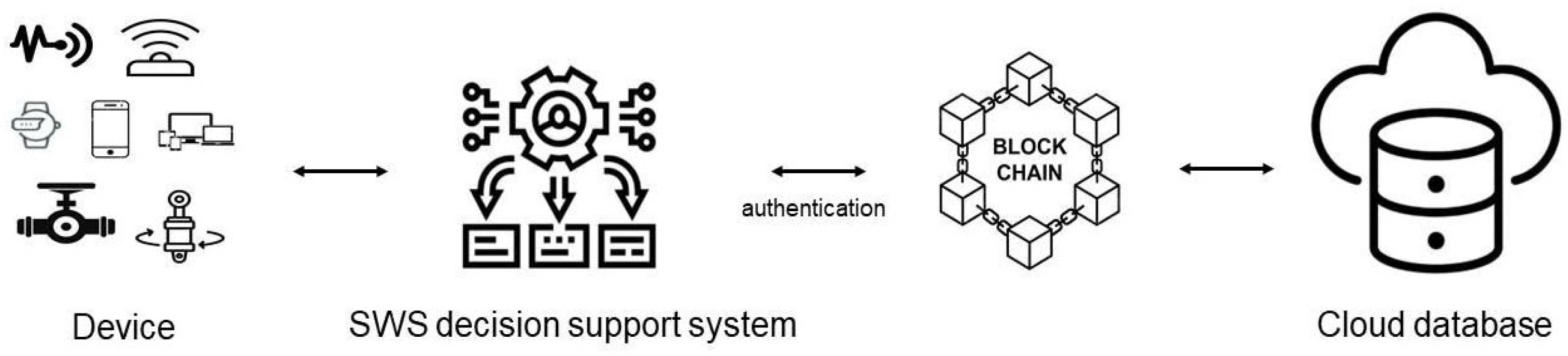

The combination system also ensures the accuracy and reliability of collected data, identifies sources and pathways of water pollution, and clarifies people’s responsibilities [

10,

89] (

Figure 3). In addition, combining these technologies allows data to be obtained on water pollution events [

89]. Due to the advantages of IoT technology over conventional sampling and analysis techniques (i.e., real-time, automatic measurement of water quality parameters and therefore saving time and manpower) [

15,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94], this technology has been used to monitor several water quality parameters, such as:

Temperature: water temperature is the concentration of thermal energy in water. It directly affects aquatic species - poikilothermic or cold-blooded organisms. It also influences physical, chemical, and biological processes in waters and consequently indirectly affects aquatic organisms.

pH: an expression of hydrogen ion concentration in water indicating basicity or acidity of water on a scale of 0 to 14, with pH 7 being neutral. pH affects most chemical and biological processes in water.

Dissolved oxygen (DO): the concentration of oxygen gas incorporated in water. DO is essential for the survival of most aquatic organisms. It is also related to oxidation and reduction reactions in water.

Salinity: the dissolved salt content of the water. It affects freshwater species and can make water unsafe for drinking, irrigation, and livestock watering.

Turbidity: the measure of relative clarity of water. Water is turbid due to the presence of clay, silt, very small substances, dissolved colored organic matter, plankton, and other microorganisms. High turbidity affects light penetration and ecological productivity.

Conductivity: the water’s ability to conduct electricity. It can be used to infer the presence of certain ions in the water; thus, significant changes in conductivity indicate a discharge of pollution sources into the aquatic environment.

Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) or redox potential: an index of the intensity of oxidation or reduction conditions in the system. It is typically measured in millivolts (mV). Positive values indicate oxidation conditions, whereas negative values indicate reduction conditions.

Chemical oxygen demand (COD): the equivalent amount of oxygen consumed in the chemical oxidation of all organic and oxidizable inorganic substances in the water. High COD levels can indicate the presence of a large amount of organic matter and oxidizable inorganic substances in the water.

4. Synthesis and Critical Analysis

Blockchain technology could be helpful for WQM, however, several gaps between the ‘current state’’ and the ‘’desired state’’ in implementing BT in this field remain. A gap analysis compares the

current state” of blockchain-WQM systems to the

“desired state” with gaps identified are provided in the

Table 1 below.

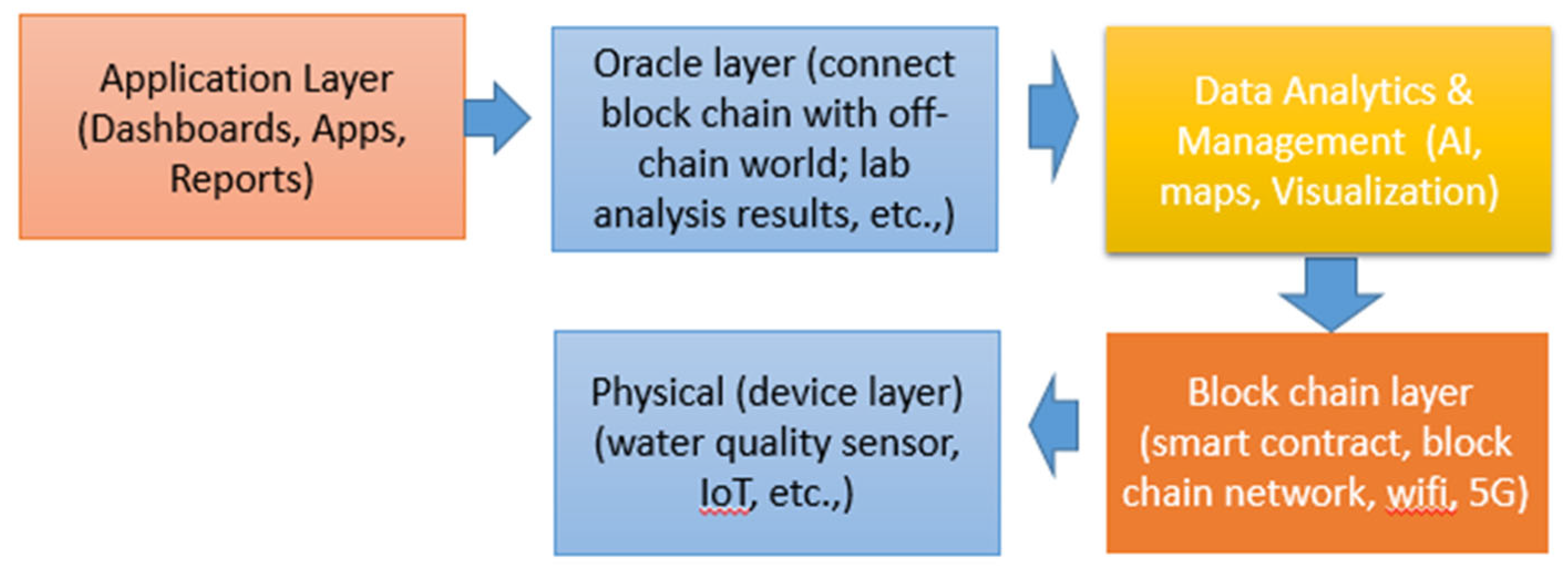

A new framework using BT for water quality monitoring is proposed in

Figure 4 below. In this framework, the integration of various technological layers required for real-time, trustworthy, and decentralized water quality monitoring and data management are showcased.

In this framework, the data will flow from the physical layer (sensors) through the oracle layer into the blockchain layer. Simultaneously, it is processed by the analytics system, which supports high-level applications in the application layer. Blockchain makes sure trust, traceability, and automation (via smart contracts), creating secure tools for water quality governance.

4.1. Case Studies in Using BT for Water Governance

Tarek Frikha et al. [

100] developed an integrated platform based on AI and smart contract to monitor and track water consumed in Tunisia. Lin, Mukhtar [

89] used a combined IoT and BCT framework for real-time monitoring and identifying polluted sources and pathways of electrical conductivity (EC) and copper (Cu2+) in the irrigation system in Taoyuan District, Taiwan. The framework comprised an IoT-based wireless sensor network for real-time WQM, a blockchain-based platform for tracing real-time water quality data, a GIS spatial detecting tool, and a model of water quality analysis simulation program (WASP). The Gcoin blockchain was applied in the traceability system. They also suggested that their proposed framework can be used in complex WQM networks, and to identify sources and pathways of water pollution. In their study, Lin, Mukhtar [

101] employed BCT to enhance real-time water monitoring and swiftly identify sources and pathways of water pollution, showcasing its effectiveness in this context

A blockchain-based framework for intelligent water management was also developed by Xia, Chen [

10]. The framework includes four parts: a data collection and transmission part, a blockchain network part, an application part, and an interaction part. The data collection and transmission part is based on the WQM system. It provides various services in collecting, transmitting, and integrating real-time data with existing databases. Each node in the blockchain network part stores and evaluates data. The data is uploaded and exchanged among nodes within the block. The blockchain network part can also be used to perform data queries and develop smart contract rules. Four application modules were set up in the application part to manage water sources, supply, utilization, and discharge. The interaction part provides an integrated platform and information portal. The proposed system showed that BCT has advantages in efficient, reliable, and secure collecting and transmitting water quality data as well as tracing water quality problems.

Agriculture consumes approximately 70% of Taiwan’s total water, with rice paddies being the primary user through traditional, water-intensive continuous flooding methods. Reported by Chen et al. [

102], A representative agricultural area in Chia-Nan District of Tainan City was chose to applied the intelligent irrigation system which based on the IoT and structured into perception, network, and application layers. It employed three irrigation strategies: Conventional Plant (CP), representing continuous flooding, and two Modified CP (MCP1 and MCP2) methods, which reduced irrigation water levels by 60-80% and allowed alternating flooding and drying, adapting AWD principles for farmer acceptance. The results consistently showed the system’s efficacy. During the dry season, water-saving rates ranged from ~2.9–6.5% (214–1150 m

3/ha saved) while in the wet season rates were higher at ~8.8–19.3% (493–1181 m

3/ha saved). Crucially, these water reductions had no significant negative impact on crop yield or other agronomic traits. In some instances, MCP strategies even led to slightly higher crop production compared to CP, particularly in the first crop season. Several lessons learned highlight the system’s value. The IoT-based approach proved highly effective in alleviating the burden of complex, labor-intensive irrigation methods, directly benefiting Taiwan’s aging agricultural workforce. The system’s customization to user needs fostered greater farmer acceptance. It successfully protected farmers’ existing rights by maintaining rice quality and yield while reducing labor costs and enhancing irrigation efficiency.

In Colombia, several IoT projects focused on smart irrigation are already underway, with plans for future 5G integration. A key area of focus is the optimization of water use in irrigation systems. For instance, in the Department of Valle del Cauca, IoT networks have been successfully applied to sugarcane crops for monitoring stations to manage irrigation effectively, leading to optimized water resources. Similarly, in the Department of Sucre, IoT is utilized to optimize water resources in squash crops. While these projects have predominantly leveraged existing communication technologies like Zigbee, GPRS, UMTS, and HSDPA for data transmission, their foundational design allows for seamless future integration with 5G, indicating a clear trajectory towards more advanced smart farming capabilities. These pilots demonstrate the tangible benefits of applying smart irrigation principles to enhance efficiency and minimize water wastage within specific Colombian agricultural contexts [

103]. Despite these promising applications, several significant challenges must be addressed for the widespread deployment and massification of 5G/IoT in Colombian agriculture. A major hurdle is the persistent digital divide in rural areas, where a considerable portion of mobile internet access still relies on older 2G and 3G technologies, thereby limiting access to the benefits of higher speeds offered by 4G and 5G. The high initial infrastructure cost of 5G implies that its initial deployment will likely concentrate in densely populated urban areas, making its extension to remote agricultural zones contingent upon specific national and regional development plans and supportive public policies. Furthermore, a significant number of Colombian farmers face economic barriers, lacking the financial means to invest in sophisticated technological tools, underscoring the necessity for economic policies from the state and mobile operators to promote the acquisition of essential equipment. Lastly, there is a critical need for technology training programs to bridge the knowledge gap often present in remote rural areas with lower educational levels, ensuring that farmers can effectively understand and utilize complex SF applications. Technical challenges, such as ensuring reliable data transmission amidst noise, fading, and interference, and managing the power consumption of user terminal equipment in remote locations to extend battery life, also remain crucial considerations for efficient 5G deployment in smart farms. Overcoming these multifaceted challenges through collaborative efforts between government, operators, and educational institutions is essential for realizing the full transformative potential of smart irrigation and precision agriculture in Colombia.

5. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

In spite of important promise of blockchain technology for water quality monitoring [

104], several challenges and limitations remain that prevent block chain technology to be widespread and practical. Deployment of block chain technology requires high cost of implementation. Setting up a blockchain system requires high costs both in terms of human capital and infrastructure. Implementing BCT in rural areas is challenging due to the infrastructure, cost, and technical limitations. Blockchain technology implementation in water quality monitoring requires high cost of investment. The blockchain infrastructure requires hardware, software, security, and distributed networking. For instance the oracle issue where the data are exchanged with physical systems [

23]. Moreover, the IoT devices used to collect data from the water monitoring stations must be integrated with blockchain, this increase operating and maintenance costs.

The scalability issues: the current blockchain network, particularly the public blockchain has a low transaction processing speed. This creates a problem when processing large volumes of sensor data from real-time water monitoring systems. Another challenge is the data input security issues. While blockchain makes data unalterable after recording, the quality of the original data still depends on the sensors and endpoints. If the device is faulty, disturbed, or hacked (e.g., sensor hacked), “bad” data will still be recorded on the blockchain [

105].

Inadequate standards and legal framework: The application of blockchain in the field of water quality monitoring or the environment in general is still new, without adequate standardization of protocols, data formats, and clear legal regulations. This makes the implementation among agencies, organizations or countries fragmented and unsynchronized.

Privacy and data access issues: Environmental data may contain sensitive information about clean water sources through environmental indicators such as COD, BOD, pH, DO, etc. or related to resource security, etc. Therefore, public sharing on blockchain needs to be carefully controlled. Questions such as who has the right to write, read, or check the data also need to be considered before applying blockchain in this field.

Challenges in expertise and human resources: Applying blockchain to water quality monitoring requires human resources with interdisciplinary knowledge of both blockchain technology, IoT, and environmental engineering. In many cases, the gap between technology experts and environmental experts makes cooperation and implementation in this field difficult.

Challenges in integrating with legacy monitoring systems: Current water monitoring systems often use traditional technology that is not immediately compatible with blockchain. Integration is time-consuming, costly, and can disrupt existing operations [

98].

Environmental Considerations in Blockchain for Water Quality Monitoring:

Blockchain technologies, especially those relying on energy-intensive consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Work (PoW), can pose significant environmental challenges, potentially undermining sustainability and climate goals [

105]. While more energy-efficient alternatives such as Proof-of-Stake (PoS) exist, their adoption alone does not ensure environmental responsibility. To effectively develop a blockchain platform for water quality monitoring, a structured, multi-layered approach is essential—one that integrates technological, institutional, regulatory, and environmental considerations. Careful evaluation and selection of blockchain protocols must balance performance and security with ecological impact, ensuring that the system aligns with broader environmental protection objectives. Below is a detailed roadmap of what needs to be done:

Future research should address these challenges through the development of cost-effective solutions, scalable blockchain architectures, robust standards, and interdisciplinary collaboration frameworks. Additionally, exploring lightweight consensus mechanisms and hybrid approaches may help balance the benefits of blockchain with environmental sustainability and practical deployment requirements in water quality monitoring systems.

6. Conclusions

In this review, blockchain technologies for water quality monitoring have been introduced, discussed, and reviewed. The Internet of Things has been utilized to monitor water quality parameters in water processing plants to identify contaminants. Block chain technology is applied to penalize any violating sectors and at the same time to ensure that violation records will be transparent and reliable. This is to ensure that monitoring activities can detect water quality in real-time and prevent any violations or contamination. This paper contributes by providing a synthesis and critical analysis of BT as well as proposing a new framework in water quality monitoring.

Blockchain technologies can be a pioneer in water systems and possibly provide new solutions for both water suppliers and water consumers. The application of blockchain technology in water facility management will enhance solution security, transparency, and reliability. In conclusion, it can be stated that with the integration of blockchain in water monitoring activities, user engagement, openness, tracking, and security were upgraded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TDH, TLT, and MKN; methodology, MKN, AH, TDH; validation, MKN, TDH, NVCN; formal analysis, MKN, TDH, NVCN, PVD. investigation, TDH, MKN, PVD, AH; resources, TLT, HPHY, NTH; data curation, APK, MKN, NTH, PVD; writing—original draft preparation, TDH, MKN, NVCN, AH, TDB, HPHY, TLT; writing—review and editing, MKN, TDH, NVCN, AH, TDB, HPHY, TLT.; visualization, NVCN, TDH, TDB; project administration, AH, TDH.; funding acquisition, AH, TDH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank Dr. Doan Van Binh of German-Vietnam University, Dr. Thanh Tam Nguyen of Griffith University, and Prof. Long D Nghiem of UTS for their support and comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| BCT |

Blockchain Technology |

| COD |

Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CPS |

Cyber-Physical Systems |

| DO |

Dissolve Oxygen |

| EC |

Electrical Conductivity |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| IoUT |

Internet of Underwater Things |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| ORP |

Oxidation-Reduction Potential |

| SCADA |

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| WASP |

Water Quality Analysis Simulation Program |

| WGT |

Water Game Tokens |

| WMS |

Wastewater Management System |

| WQM |

Water Quality Monitoring |

| WSN |

Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- Jiang, J.; Tang, S.; Han, D.; Fu, G.; Solomatine, D.; Zheng, Y. A Comprehensive Review on the Design and Optimization of Surface Water Quality Monitoring Networks. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 132, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-W.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, M.K.; Hussain, A.; Bui, X.-T.; Ngo, H.H. A Review of Biosensor for Environmental Monitoring: Principle, Application, and Corresponding Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behmel, S.; Damour, M.; Ludwig, R.; Rodriguez, M.J. Water Quality Monitoring Strategies—A Review and Future Perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardila, A.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Pelletier, G. Spatiotemporal Optimization of Water Quality Degradation Monitoring in Water Distribution Systems Supplied by Surface Sources: A Chronological and Critical Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 337, 117734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcellos, D.d.S.; Souza, F.T.d. Optimization of Water Quality Monitoring Programs by Data Mining. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, D.A.; Shapiro, J.S. Consequences of the Clean Water Act and the Demand for Water Quality. Q. J. Econ. 2019, 134, 349–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, Y.A.; Govindan, K.; Murniningsih, R.; Setiawan, A. Industry 4.0 Based Sustainable Circular Economy Approach for Smart Waste Management System to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.-D.; Ky, N.M.; Thuong, N.T.N.; Nhan, H.Q.; Ngan, N.V.C. Artificial Intelligence in Pollution Control and Management: Status and Future Prospects. In Artificial Intelligence and Environmental Sustainability: Challenges and Solutions in the Era of Industry 4.0; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofer, M.; Gomber, P.; Hinz, O.; Schiereck, D. Blockchain. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Chen, X.; Song, C. A Framework of Blockchain Technology in Intelligent Water Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 909606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Misra, S.K.; Rana, N.P.; Raghavan, V.; Akella, V. Blockchain Research, Practice and Policy: Applications, Benefits, Limitations, Emerging Research Themes and Research Agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincheira, M.; Vecchio, M.; Giaffreda, R.; Kanhere, S.S. Cost-Effective IoT Devices as Trustworthy Data Sources for a Blockchain-Based Water Management System in Precision Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, K.; Yousef, B.A.A.; AlMallahi, M.N.; Tan, Y.C.; Mahmoud, M.; Jaber, H.; et al. An Overview of Smart Irrigation Systems Using IoT. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, K.; Anusuya, E.; Kumar, R.; Son, L.H. Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring Using Internet of Things in SCADA. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdury, M.S.U.; Emran, T.B.; Ghosh, S.; Pathak, A.; Alam, M.M.; Absar, N.; et al. IoT Based Real-Time River Water Quality Monitoring System. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 155, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. Can Blockchain Strengthen the Internet of Things? IT Prof. 2017, 19, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakak, S.; Khan, W.Z.; Gilkar, G.A.; Haider, N.; Imran, M.; Alkatheiri, M.S. Industrial Wastewater Management Using Blockchain Technology: Architecture, Requirements, and Future Directions. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020, 3, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.I.A.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Alshdadi, A.A. Internet of Things (IoT)-Based Wastewater Management in Smart Cities. Electronics 2023, 12, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Thakur, S.; Dixit, M.; Katkam, R.; Agrawal, A.; Kazi, F. Blockchain and Anomaly Detection Based Monitoring System for Enforcing Wastewater Reuse. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berlian, M.H.; Sahputra, T.E.R.; Ardi, B.J.W.; Dzatmika, L.W.; Besari, A.R.A.; Sudibyo, R.W.; et al. Design and Implementation of Smart Environment Monitoring and Analytics in Real-Time System Framework Based on Internet of Underwater Things and Big Data. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Electronics Symposium (IES), Surabaya, Indonesia, 29–30 September 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajudin, M.K., Sarijari, M.A., Ibrahim, A.K.M., Rashid, R.A., Eds.; Blockchain-Based Internet of Thing for Smart River Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Fan, T.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Shankar, A.; Manickam, A. Big Data Analytics and IoT in Operation Safety Management in Under Water Management. Comput. Commun. 2020, 154, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satilmisoglu, T.K.; Sermet, Y.; Kurt, M.; Demir, I.S. Blockchain Opportunities for Water Resources Management: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bamisile, O.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Luo, S.; Huang, Q.; et al. Decarbonization of China’s Electricity Systems with Hydropower Penetration and Pumped-Hydro Storage: Comparing the Policies with a Techno-Economic Analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Hua, W. Effects of Cascade Reservoir Dams on the Streamflow and Sediment Transport in the Wujiang River Basin of the Yangtze River, China. Inland Waters 2018, 8, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, D.V.; Kantoush, S.A.; Saber, M.; Mai, N.P.; Maskey, S.; Phong, D.T.; et al. Long-Term Alterations of Flow Regimes of the Mekong River and Adaptation Strategies for the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 32, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, L.S.; Paraschiv, S. Contribution of Renewable Energy (Hydro, Wind, Solar and Biomass) to Decarbonization and Transformation of the Electricity Generation Sector for Sustainable Development. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Guide to Hydrological Practice – Volume II: Management of Water Resources and Application of Hydrological Practices; WMO-No. 168; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Chen, W.; Hu, B.; Xu, Y.J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; et al. Roles of Reservoirs in Regulating Basin Flood and Drought Risks under Climate Change: Historical Assessment and Future Projection. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 48, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, P.S.; Kwon, H.-H.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, J.-H. Modeling, Challenges, and Strategies for Understanding Impacts of Climate Extremes (Droughts and Floods) on Water Quality in Asia: A Review. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, L.; Villarini, G.; Archfield, S.; Faulkner, D.; Lamb, R.; Khouakhi, A.; et al. Global Changes in 20-Year, 50-Year, and 100-Year River Floods. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Alfieri, L.; Wyser, K.; Mentaschi, L.; Betts, R.A.; Carrao, H.; et al. Global Changes in Drought Conditions under Different Levels of Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, F.; Huggel, C.; Hoyos, N.; Scott, C.A. Hydrology, Water Resources Availability and Management in the Andes under Climate Change and Human Impacts. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 49, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Try, S.; Tanaka, S.; Tanaka, K.; Sayama, T.; Lee, G.; Oeurng, C. Assessing the Effects of Climate Change on Flood Inundation in the Lower Mekong Basin Using High-Resolution AGCM Outputs. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Tian, F.; Yang, T.; Wen, J.; Khan, M.Y.A. Development of a Comprehensive Framework for Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change and Dam Construction on Flow Regimes. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, S.; Dai, J.; Yu, L.; Xue, W.; et al. A Framework for Methodological Options to Assess Climatic and Anthropogenic Influences on Streamflow. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 645746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Ma, T.; et al. Future Changes in Water Resources, Floods and Droughts under the Joint Impact of Climate and Land-Use Changes in the Chao Phraya Basin, Thailand. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brêda, J.P.L.F.; Cauduro Dias de Paiva, R.; Siqueira, V.A.; Collischonn, W. Assessing Climate Change Impact on Flood Discharge in South America and the Influence of Its Main Drivers. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Hall, J.; Viglione, A.; Perdigão, R.A.P.; Parajka, J.; Merz, B.; et al. Changing Climate Both Increases and Decreases European River Floods. Nature 2019, 573, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binh, D.V.; Kantoush, S.; Sumi, T. Changes to Long-Term Discharge and Sediment Loads in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta Caused by Upstream Dams. Geomorphology 2020, 353, 107011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, T.A.; Someth, P.; Lauri, H.; Koponen, J.; Sarkkula, J.; Kummu, M. Observed River Discharge Changes Due to Hydropower Operations in the Upper Mekong Basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 545, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalise, D.R.; Sankarasubramanian, A.; Ruhi, A. Dams and Climate Interact to Alter River Flow Regimes across the United States. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.T.N.; Kumar, L. Application of Remote Sensing and GIS-Based Hydrological Modelling for Flood Risk Analysis: A Case Study of District 8, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1792–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, D.V.; Kantoush, S.A.; Sumi, T.; Mai, N.P.; Ngoc, T.A.; Trung, L.V.; et al. Effects of Riverbed Incision on the Hydrology of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.Q.; Kantoush, S.; Binh, D.V.; Saber, M.; Vo, D.N.; Sumi, T. Understanding the Anthropogenic Development Impacts on Long-Term Flow Regimes in a Tropical River Basin, Central Vietnam. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2023, 68, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriyono, E. Digitizing Water Management: Toward the Innovative Use of Blockchain Technologies to Address Sustainability. Cogent Eng. 2020, 7, 1769366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogo, E.M.; Salami, A.F.; Nwulu, N.I.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Blockchain and Internet of Things-Based Technologies for Intelligent Water Management System. In Artificial Intelligence in IoT; Al-Turjman, F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonia, V.; Goyal, M.K.; Gupta, B.B.; Gupta, A.K.; Jha, S.; Das, J. Drought Occurrence in Different River Basins of India and Blockchain Technology Based Framework for Disaster Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangan, A.; Chiru, C.-G.; Arsene, D.; Czako, Z.; Lisman, D.F.; Mocanu, M.; et al. Advanced Techniques for Monitoring and Management of Urban Water Infrastructures—An Overview. Water 2022, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, E.; Wang, M. (Eds.) Application and Prospect Analysis of Blockchain Technology in Water Resources Protection. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Information Security (ICBCTIS), Guangzhou, China, 15–17 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuno, T.; Ishii, A.; Amakata, M.; Fujii, J. (Eds.) Smart Dam: Upstream Sensing, Hydro-Blockchain, and Flood Feature Extractions for Dam Inflow Prediction. In Advances in Information and Communication; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majia, L. (Ed.) Innovative Research of Blockchain Technology in the Field of Computer Monitoring of Hydropower Station. In Proceedings of the 2021 Second International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Coimbatore, India, 4–6 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukrutha, V.L.T.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E.; Ray, C. (Eds.) G-DaM: A Blockchain-Based Distributed Robust Framework for Ground Water Data Management. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Smart Electronic Systems (iSES), Agra, India, 18–22 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Sanjari, M.; Saif, M. (Eds.) A Real-Time Blockchain-Based Multifunctional Integrated Smart Metering System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), Manhattan, KS, USA, 25–26 April 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Chen, X.; Song, C. A Framework of Blockchain Technology in Intelligent Water Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 909606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.; Shekhawat, U. Blockchain for Sustainable E-Agriculture: Literature Review, Architecture for Data Management, and Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torky, M.; Hassanein, A.E. Integrating Blockchain and the Internet of Things in Precision Agriculture: Analysis, Opportunities, and Challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.M.; Borole, Y.D.; Rout, S.; Negi, P.; Deivakani, M.; Dilip, R. (Eds.) Inclusion of Cloud, Blockchain and IoT Based Technologies in Agriculture Sector. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Jakarta, Indonesia, 22–23 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Jain, V.; Sharma, B.; Chatterjee, J.M.; Shrestha, R. Smart City Infrastructure: The Blockchain Perspective; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Drăgulinescu, A.M.; Bălăceanu, C.; Osiac, F.E.; Roşcăneanu, R.; Chedea, V.S.; Suciu, G.; et al., Eds. IoT-Based Smart Water [... incomplete entry – please provide the rest of the title or source].

- Drăgulinescu, A.M.; Constantin, F.; Orza, O.; Bosoc, S.; Streche, R.; Negoita, A.; et al. Smart Watering System Security Technologies Using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Pitesti, Romania, 1–3 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.S.; Bajwa, I.S.; Cheema, S.M. An Intelligent and Secure Smart Watering System Using Fuzzy Logic and Blockchain. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2019, 77, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chethan, R.C.; Roopa, B.; Sahana, D.K. A Survey on Water Quality Monitoring System Using IoT and Blockchain. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2020, 6, 998–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, P.B.J. Surface Water Quality Monitoring; European Topic Centre on Inland Waters, European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, J.; Balance, R. Water Quality Monitoring—A Practical Guide to the Design and Implementation of Freshwater Quality Studies and Monitoring Programmes; UNEP and WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, S. The 5 Essential Elements of a Hydrological Monitoring Programme; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. UNEP. Monitoring Water Quality; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, Year Unknown. Available online: https://www.unep.org (accessed on Day Month Year).

- US EPA. An Introduction to Water Quality Monitoring; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Surface Water Quality Monitoring; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, M. Surface Water Monitoring. In Water Quality and Standards—Volume 1; EOLSS Publications: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; UNICEF. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five Years into the SDGs; World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia. Canada–BC Water Quality Monitoring Program; Government of British Columbia: British Columbia, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mekong River Commission (MRC). Water Quality Conditions; MRC: Vientiane, Lao PDR, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tulip, S.S.; Siddik, M.S.; Islam, M.N.; Rahman, A.; Haghighi, A.T.; Mustafa, S.T. The Impact of Irrigation Return Flow on Seasonal Groundwater Recharge in Western Bangladesh. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 266, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Sun, X.; Cheng, M.; Cheng, H.; Li, Z. Optimizing Irrigation Amount and Potassium Rate to Simultaneously Improve Tuber Yield, Water Productivity and Plant Potassium Accumulation of Drip-Fertigated Potato in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 264, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, R.; Du, X.; Ma, S.; Chen, N.; Gao, S. A Summary of the Research on the Foundation and Application of Blockchain Technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1693, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Rui, L.; Lei, M. Distributed Incentive Mechanism Based on Hyperledger Fabric. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2224, 012130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Zaffiro, A.; Marx, R.; Kefauver, P.; Krishnan, R.; Haught, R.; Herrmann, J. On-Line Water Quality Parameters as Indicators of Distribution System Contamination. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2007, 99, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahontu, B.I.; Petcu, A.; Predescu, A.; Arsene, D.; Mocanu, M. A Blockchain Approach for Migrating a Cyber-Physical Water Monitoring Solution to a Decentralized Architecture. Water 2023, 15, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Y.P. How Blockchain Technology Could Improve the Quality of Drinking Water in Puerto Rico. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecchini, M. Data Collection, Storage and Processing for Water Monitoring Based on IoT and Blockchain Technologies; Sapienza University of Rome: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fascista, A. Toward Integrated Large-Scale Environmental Monitoring Using WSN/UAV/Crowdsensing: A Review of Applications, Signal Processing, and Future Perspectives. Sensors 2022, 22, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.; Zhou, T.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. A Blockchain-Based Location Privacy Protection Incentive Mechanism in Crowd Sensing Networks. Sensors 2018, 18, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogo, E.M.; Salami, A.F.; Nwulu, N.I.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Blockchain and Internet of Things-Based Technologies for Intelligent Water Management System. In Artificial Intelligence in IoT: Transactions on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Chen, X.; Song, C. A Framework of Blockchain Technology in Intelligent Water Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 909606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Application of Blockchain Technology in Water Management and New Energy Economic Development. Water Supply 2023, 23, 4227–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.W.; Choo, K.Y. Design of a Smart Water Storage and Trading Platform Based on Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of MECON 2022–2023; pp. AER 214; 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- An, C.T.; Tai, T.M.; Huy, P.L.N.; Ngoc, P.H. Blockchain-Based Platform for IoT Sensor Data Management. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Data Science; 2023; pp. 138–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Mukhtar, H.; Huang, K.-T.; Petway, J.R.; Lin, C.-M.; Chou, C.-F.; et al. Real-Time Identification of Irrigation Water Pollution Sources and Pathways with a Wireless Sensor Network and Blockchain Framework. Sensors 2020, 20, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budiarti, R.P.N.; Tjahjono, A.; Hariadi, M.; Purnomo, M.H. Development of IoT for Automated Water Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computer Science, Information Technology, and Electrical Engineering (ICOMITEE), Jember, Indonesia, 16–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.; Gouthami, S. Internet of Things Enabled Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring System. Smart Water 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Marques, G. Internet of Things for Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. In Hassanien, A.E.; Bhatnagar, R., Darwish, A. (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development: Theory, Practice and Future Applications, Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Bapery, C.; Hossain, M.J.; Hassan, Z.; Hossain, G.M.J.; Islam, M.M. Internet of Things (IoT) Based Water Quality Monitoring System. Int. J. Multidiscip. Curr. Educ. Res. 2020, 2, 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar, N.; Ramya, R. The Real-Time Monitoring of Water Quality in IoT Environment. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS), Coimbatore, India, 19–20 March 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Mukhtar, H.; Huang, K.-T.; Petway, J.R.; Lin, C.-M.; Chou, C.-F.; et al. Real-Time Identification of Irrigation Water Pollution Sources and Pathways with a Wireless Sensor Network and Blockchain Framework. Sensors 2020, 20, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Fu, D.; Yang, M.; Lin, S.; Zongzhong, S.; Liu, W.J.; et al. Research on Improving the Quality of Groundwater Self-Monitoring via Blockchain Technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 112, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Kizhakkethottam, J.J.J.T. Research on Intelligent River Water Quality Management System Using Blockchain–Internet of Things. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2024, 22, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Chen, X.; Song, C.J. A Framework of Blockchain Technology in Intelligent Water Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 909606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriyono, E. Digitizing Water Management: Toward the Innovative Use of Blockchain Technologies to Address Sustainability. J. Clean. Environ. 2020, 7, 1769366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frikha, T.; Ktari, J.; Amor, N.B.; Chaabane, F.; Hamdi, M.; Denguir, F.; et al. Low Power Blockchain in Industry 4.0 Case Study: Water Management in Tunisia. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 96, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Mukhtar, H.; Huang, K.-T.; Petway, J.R.; Lin, C.-M.; Chou, C.-F.; et al. Real-Time Identification of Irrigation Water Pollution Sources and Pathways with a Wireless Sensor Network and Blockchain Framework. Sensors 2020, 20, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-T.; Lin, G.-F. Practical Application of an Intelligent Irrigation System to Rice Paddies in Taiwan. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrubla-Hoyos, W.; Ojeda-Beltrán, A.; Solano-Barliza, A.; Rambauth-Ibarra, G.; Barrios-Ulloa, A.; Cama-Pinto, D.; et al. Precision Agriculture and Sensor Systems Applications in Colombia through 5G Networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kasahara, S.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wan, J. Smart Contract-Based Access Control for the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Victor, N.; Chengoden, R.; Ramalingam, M.; Selvi, G.C.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; et al. Blockchain for Internet of Underwater Things: State-of-the-Art, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2022, 14, 15659–15684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).